Yves here. “Right to die” is a product of Christian prohibitions against suicide. After all, none of us gets out of here alive. However, the issue of pain or severe debility among the old and not necessarily so old is seldom discussed in polite company. My father shot himself when he could no longer endure the horrific symptoms of an autoimmune disease that was always fatal. One of my parents’ friends had successfully fought off breast cancer a couple of times. When it recurred and she was facing regular intubations to drain her lungs, and not high odds that treatment would work, she took a lethal dose of sleeping pills she’d hoarded. Another friend of my mother’s simply quit taking her meds and stopped eating. She died in a few weeks.

As one friend said about my father’s suicide: “He was a hunter so he at least knew how to do it right.” This isn’t completely a joke. Harvard’s Medical School shows that suicide by gun succeeds only 82.5% of the time. I shudder to think what exactly became of the other 17.5%. I will similarly spare you an account from a friend of a failed suicide by Drano.

However, since it’s entirely rational to be depressed these days, plus old and infirm people are already exploited in far too many ways (everything from greedy heirs to Lambert’s “Insert tube, extract rents” model), having rules and procedures makes sense, both for the person who is thinking about exiting a bit early, and any medical professionals who might assist them. And as you will see from this story, we are not at all far along in the US on how to approach this issue.

By Katheryn Houghton, Montana Correspondent, is covering all things health care across the state for Kaiser Health News. Originally published at Kaiser Health News

Linda Heim knew her dad didn’t plan to wait for the cancer to kill him. For decades, he’d lived in Montana, which they’d thought was one of the few places where terminally ill people could get a prescription to end their life.

After two years of being sick, Heim’s dad got the diagnosis in 2019: stage 4 kidney cancer. His physician offered treatments that might extend his life by months. Instead, the 81-year-old asked the doctor for help dying. Heim said her parents left the appointment in their hometown of Billings with two takeaways: The legality of medically assisted death was questionable in Montana, and her father’s physician didn’t seem willing to risk his career to put that question to the test.

“My parents knew when they left there that was the end of that conversation,” said Heim, now 54. “My dad was upset and mad.”

The day after the appointment, Heim’s mother went grocery shopping. While she was gone, Heim’s dad went to the backyard and fatally shot himself. (Heim asked that her father’s name not be published due to the lingering stigma of suicide.)

About a decade earlier, in 2009, the Montana Supreme Court had, in theory, cracked open the door to sanctioned medically assisted death. The court ruled physicians could use a dying patient’s consent as a defense if charged with homicide for prescribing life-ending medication.

However, the ruling sidestepped whether terminally ill patients have a constitutional right to that aid. Whether that case made aid in dying legal in Montana has been debated ever since. “There is just no right to medical aid in dying in Montana, at least no right a patient can rely on, like in the other states,” said former state Supreme Court Justice Jim Nelson. “Every time a physician does it, the physician rolls the dice.”

Every session of the biennial Montana state legislature since then, a lawmaker has proposed a bill to formally criminalize physician-assisted death. Those who back the bills say the aid is morally wrong while opponents say criminalizing the practice would be a backstep for patients’ rights. But so far, lawmakers haven’t gained enough support to pass any legislation on the issue, though it has been close. The latest effort stalled on March 1, on a split vote.

Even the terminology to describe the practice is disputed. Some say it’s “suicide” anytime someone intentionally ends their life. Others say it’s “death with dignity” when choosing to expedite a painful end. Such debates have gone on for decades. But Montana remains the sole state stuck in a legal gray zone, even if the practice can still seem taboo in many states with clear laws. Such continued uncertainty makes it especially hard for Montana patients like Heim’s dad and their doctors to navigate what’s allowed.

“Doctors are risk-averse,” said Dr. David Orentlicher, director of the health law program at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, who helped write clinical aid-in-dying guidelines published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine in 2016. “The fear of being sued or prosecuted is still there.”

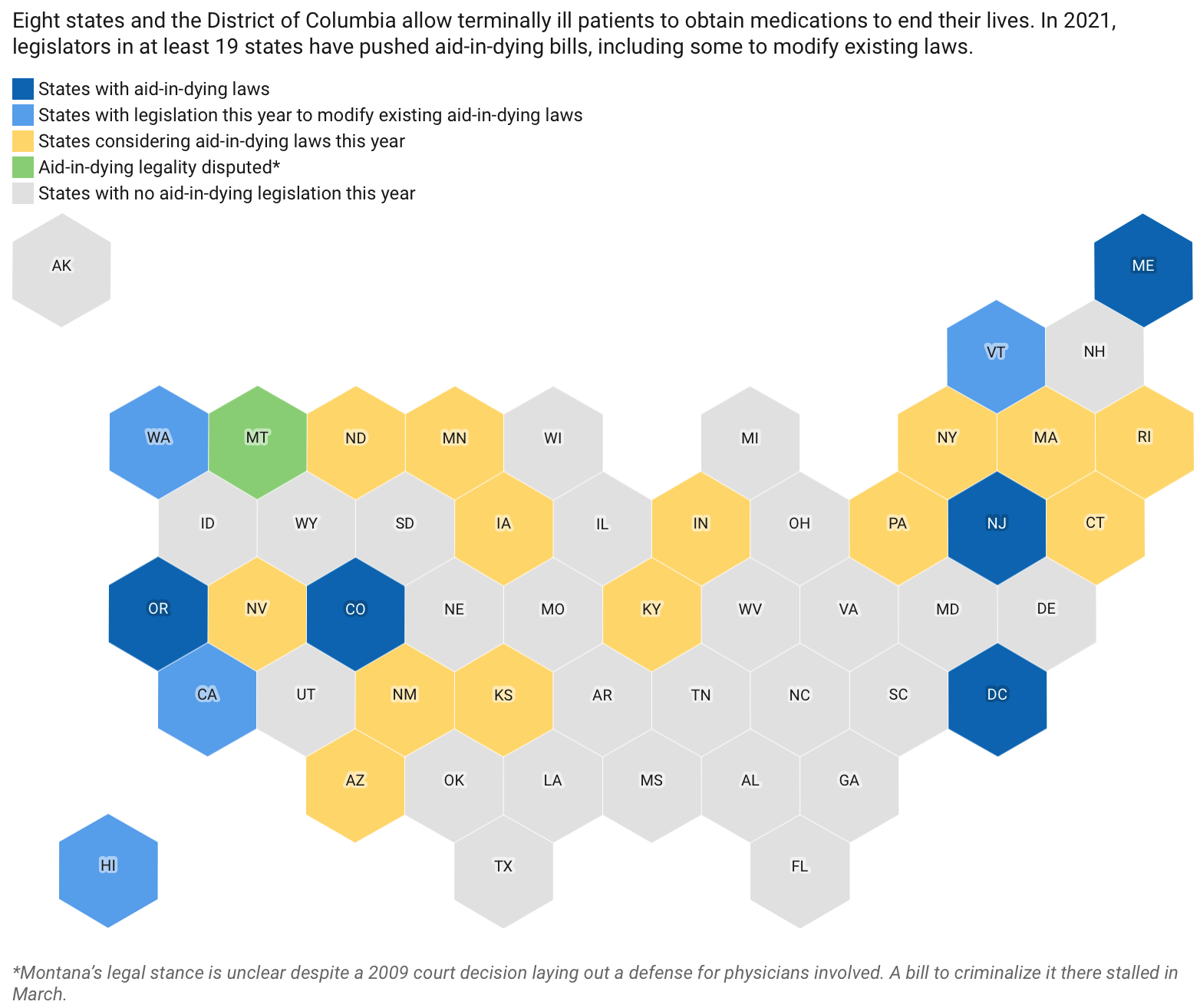

Despite that, access to medical aid in dying is gaining momentum across the U.S. Outside Montana, eight states and the District of Columbia allow the life-ending aid — six of them since 2014. So far in 2021, legislators in at least 19 states have pushed aid-in-dying bills, most seeking to legalize the practice and some seeking to drop barriers to existing aid such as expanding which medical professionals can offer it. Many are repeat legalization efforts with some, like in New York, dating as far back as 1995. Only the Montana bill this year specifically sought to criminalize it.

North Dakota considered legislation to legalize medically assisted death for the first time. Rep. Pamela Anderson, a Democrat from Fargo who proposed the measure after hearing from a cancer patient, said she wasn’t surprised when the bill failed in February in a 9-85 vote. The state’s medical association said it was “incompatible with the physician’s role as healer.” Angry voters called Anderson asking why she wanted to kill people.

“But I heard from just as many people that this was a good bill,” Anderson said. “There is momentum to not let this concept go away.”

Back in Montana, now retired state Supreme Court Justice Nelson said he has always regretted joining the majority in the case that allowed the practice because the narrow ruling focused on physicians’ legal defense, not patients’ rights. Having watched a friend die slowly from disease, Nelson, 77, wants the choice himself if ever needed.

Despite — or because of — the court decision, some Montana doctors do today feel that they can accommodate such patient decisions. For example, Dr. Colette Kirchhoff, a hospice and palliative care physician, said until she retired from private practice last year she considered patients’ requests for life-ending drugs.

Physicians who help in such cases follow well-established guidelines set by other states, Kirchhoff said. A patient must have six months or less to live — a fact corroborated by a second physician; can’t be clinically depressed; needs to ask for the aid; and be an adult capable of making health care decisions, which is determined by the attending physician. They must also administer the life-ending medication themselves.

“You’re obviously not going to do a case that is vague or nebulous or has family discord,” Kirchhoff said. “The doctors who are prescribing have felt comfortable and that they’re doing the right thing for their patient, alleviating their suffering.” Of her few patients who qualified for a prescription, she said, none actually took the drugs. Kirchhoff noted that, in some cases, getting the prescription seemed to provide comfort to her patients — it was enough knowing they had the option if their illness became unbearable.

For the past six legislative sessions — dating to 2011 — a Montana lawmaker has proposed a bill to clarify that state law doesn’t allow physician-assisted death. Republican Sen. Carl Glimmpicked up that effort the past two sessions. Glimm said the current status, based on the more than decade-old court decision, sends a mixed message in a state that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranks as having among the nation’s highest suicide rates. Glimm said allowing someone to end their life because of pain from a terminal illness could normalize suicide for people living with depression, which is also a form of pain.

“It’s really hard because I do sympathize with them,” Glimm said. “What it boils down to is, if you’re going to take your own life, then that’s suicide.”

Kim Callinan, president and CEO of national nonprofit Compassion & Choices, said the comparison to suicide is frustrating. “People who are seeking medical aid in dying want to live, but they are stricken with a life-ending illness,” she said.

Glimm and his bill’s supporters say that some patients could be pressured into it by family members with something to gain, and doctors could prescribe it more often than they should.

But Callinan, whose group advocates for aid in dying, said that since Oregon first legalized it in 1997, no data has shown any merit to the warnings about abuse and coercion. One study showed no evidence of heightened risk of abuse within the practice for vulnerable populations such as the elderly. But critics have said states aren’t doing enough to track the issue.

By now, Leslie Mutchler, 60, knows most of the people on all sides of the debate after years of testifying in support of protecting aid in dying. Her dad, Bob Baxter, was a plaintiff in the case that eventually led to the 2009 Montana Supreme Court decision on medically assisted death. After leukemia whittled his body for years, he died in 2008 without the option, the same day a lower court ruled in his favor.

Mutchler said she didn’t understand how complicated the Supreme Court’s ultimate ruling was until her son TJ was diagnosed with terminal metastatic pancreatic cancer in 2016.

He was 36 and lived in Billings, Montana. By then, the 6-foot-5 man had lost 125 pounds off what had been a 240-pound frame. He couldn’t keep food down and needed a feeding tube for medicine and water. TJ Mutchler wanted to have the choice his grandfather never got. But when he went to his physician and asked for aid in dying, the response was it wasn’t legal. Eventually, Mutchler found a doctor to evaluate her son and write the prescriptions for phenobarbital and amitriptyline. TJ took the drugs more than two months later and died.

“People contact me asking how to find someone and it’s difficult,” Mutchler said. “That’s why people end up taking matters into their own hands.” Research into terminally ill populations is limited, but one national study published in 2019 found the risk of someone with cancer taking their own life is four times higher than the general population.

Roberta King’s dad, Bob Baxter, was a plaintiff in the 2009 Montana Supreme Court case that opened the door to medically assisted death, which state legislators have since regularly tried to formally criminalize. King, shown testifying in favor of aid-in-dying protections on Feb. 26, 2021, hasn’t missed a hearing on such bills. (Screengrab via Montana Legislative Services Division)

For Roberta King, another one of Baxter’s daughters, the ongoing fight over aid in dying in Montana means she knows every other winter she’ll make the more than 200-mile round trip from her Missoula home to the state capital. King, 58, has testified against all six bills that sought to ban aid in dying following her dad’s case. She memorized a speech about how her dad became so thin after his medicine stopped working that it hurt for him to sit.

“It’s still terrible, you still have to get up there in front of everybody and they know what you’re going to say because it’s the same people doing the same thing,” King said. But skipping a hearing doesn’t feel like an option. “If something were to happen to this and I didn’t try, I would never forgive myself,” she said.

Terry Pratchett on this

He there describes as his father died of pancreatic cancer, which I can relate to, as my mum died in exactly the same way “as a kind of collateral damage in the war between […] cancer and the morphine”

I’m sorry to hear about your dad. I’ve had ideation but I’m currently seeing a social worker about it

As a friend of mine once said regarding euthanasia: “In this country we treat dogs better than we treat humans.” In November, 2017, a Dutch friend used the Dutch assisted suicide law to die. Following a kidney transplant that only worked so long as the immuno-suppressant drugs were provided, cancer ravaged his body. Since he was under ongoing care, he was able to find two physicians to immediately agree that he qualified for euthanasia under Dutch law. A date was set, the procedure occurred in his home with a father-daughter doctor team (Dutch law requires two physicians be present) and his immediate family by his bedside. One drug was administered first to make sure he was totally asleep (similar to an anaesthetic prior to surgery) and then the euthanasia drugs were added to the IV mix. His wife said it was all done very compassionately and professionally, and the family was grateful to see his intense suffering end. As a friend, I was grateful to be able to send a final letter with my respects, affection and encouragement. Death with dignity should be as much a part of a physician’s training as life with dignity.

I had an aunt and uncle on my mother’s side opt for euthanasia as they were both terminal cancer patients (and lived in the Netherlands) – My uncle was in 1988, my aunt in the late 2000s (I forgot the year.) I met my aunt several times over the years, and I was fortunate to meet my uncle once when I took my first trip to the Netherlands since I was very little.

[“Right to die” is a product of Christian prohibitions against suicide.]

The prohibitions remain; although, time and social conventions have somewhat muted the more extreme responses:

“Even in 1749, in the full blaze of the philosophic movement, we find a suicide named Portier dragged through the streets of Paris with his face to the ground, hung from a gallows by his feet, and then thrown into the sewers; and the laws were not abrogated till the Revolution, which, having founded so many other forms of freedom, accorded the liberty of death. [W.E.H. Lecky, “History of European Morals,” 1869]

In England, suicides were legally criminal if of age and sane, but not if judged to have been mentally deranged. The criminal ones were mutilated by stake and given degrading burial in highways until 1823.”

Nietzsche preferred a more neutral term, one unencumbered by the negative, historical religious admonitions and the baggage of social/legal censures, i.e., ‘voluntary death’, viz.,

“Many too many live and they hang on their branches much too long. I wish a storm would come and shake all this rottenness and worm-eatenness from the tree! I wish preachers of speedy death would come! They would be the fitting storm and shakers of the trees of life!”

https://philosophynow.org/issues/76/Dying_At_The_Right_Time

Compare with Seneca, for example,

https://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/2010/01/seneca-the-younger-on-suicide-letter-70-and-77/

The slow march to find a suitable societal moral philosophical middle ground, if and when it is ever arrived at, will surely never satisfy everyone. It is the inevitable truth contained in the rawness of individual finality and its awareness that offers up extreme responses. Death is not ‘pretty’, it is an ugly reality for at least some individuals, maybe all, who have had the first hand experience of watching someone they are close to slowly die, as the biological will to live is very strong indeed. Voluntary death, one supposes, is the means to overcome that contradiction.

We lost my mother to ovarian cancer about 2 years after an unfortunately delayed diagnosis. She weighed about 75 pounds, down from 160, all her organs full of metastases. She was incredibly stoic and held on and fought like heck to stay alive, despite the physical wasting and bedsores and pain, lots of pain. This was in 1973. There wasn’t much in the way of hospice back then.

My mom was a very smart woman. She was working on a masters in endocrinology when WW II intervened. Her mother had succumbed to pancreatic cancer, also after a long period of wasting and pain, as had other people close to her, so she knew what was coming. But the family was so shut down that we could never have discussed the intentional-death option.

In the end, she just wanted to die at home, but in hope-against-hope cruelty we bundled her off to the hospital, looking for some miracle but ending only with a nice sanitary death. Which came about because the doctors dosed her with increasing loads of opioids, mostly Demerol, until she stopped breathing.

I’ve noted in past comments the unholy interest the private equity boys and girls have in acquiring hospice facilities and systems. https://hospicenews.com/2021/02/16/private-equity-bullish-on-hospice-in-2021/ And I recall they also have some involvement in the writing and passage of legislation legalizing and supporting assisted suicide. A cynic like myself might put this down to the intent to maybe franchise a long string of end-of-life facilities, like the one portrayed in “Soylent Green,” or maybe more like the disgusting bottom-line-driven Medicaid “care facilities.”

Obviously this is a very fraught area of human-need-human-greed-jurisprudence interaction. Notions of liberty run up against the kinds of blandishments and incentives that business types might use to increase their take of the “health care dollar.”

thanks for posting that link on private equity and hospice care….very concerning..

I would just add as the sister of a twin brother who committed suicide and then my spouse who died of Stage 4 cancer in home hospice last year while covid restrictions were heavy, that I think everyone is different.

My husband hung on in terrible pain heavily medicated for 17 months…was given 8-16 months with or without treatment…It’s really unspeakable what me and our son witnessed with the terrible hospice care we got at home for 7 long months. Terrible in that they weren’t trained for stage 4 cancers at home.

Nonetheless my husband did NOT want to die…..nope..the courage I saw is beyond anything I’ve seen in my 68 years of life..

Not sure anyone really knows in advance what one will want to do…I know I suspended any idea of knowing how I myself would feel once he passed…Let’s not kid ourselves that we know in advance.

Tis a tough one for me on this discussion.

Indeed. I sometimes wonder if the prohibition against assisted suicide is to protect the mental health and anguish and guilt of those who would be called upon to do the “assisting”. This is a fraught question. Having watched a parent endure agony and wishing to die to escape that agony, I still cannot say I could have agreed to my parent’s intentional death by external interferance, if asked. Does that make me horrible or human? Surely laws against prescribing pain killing drugs to the terminally ill lest they become “addicted” (what a cruel joke) need to be rethought.

Yves, I too am sorry to read your father’s story. You certainly are/have been up against it, in a lot of ways. And the work you and your colleagues do with NC is perhaps the most valuable on the internet.

No one should have to go through the situation that your dad encountered. Oregon has its problems, but assisted suicide is available here, and the system, if a little clunky – a bottle of valiums – works.

Warren Zeavon, when he learned he was not long for this earth, produced a couple of very fine albums on the subject of our inevitable departure.

I don’t think many people today would contest the “right” if that’s the word of people to commit suicide if they want to. It’s been an awkward affair in most cultures, but in ours it’s essentially a residue of the Christian belief that out life is God’s to end, not ours. That being so, the decay of religious belief makes the injunction against suicide rather academic.

But that’s not what’s being discussed here: as often the question of voluntary suicide is elided with the question of the “right” (or at least the ability) of health professionals to help people die, which, whatever you think of the merits, is an entirely different thing. The problem, of course is that for all such subjects it’s hard to say where the line of acceptability should be drawn. The criteria given above – within six months of death etc. – will seem reasonable to most people. Likewise, one can imagine another set of criteria (more than 50% chance of death within two years, willingness inferred if patient not able to communicate etc.) which most people would find unacceptable, at least today. But where do you draw the line and how far are you prepared to move it? The problem with all relativist arguments (and no, I don’t have the answer) is that there is no obvious point at which to stop, and no obvious mechanism for deciding. Thus, once you agree a principle of this kind, you have no idea where you will end up in ten or twenty years, and that has to be accepted at the start.

God forbid the PE or health insurance, aka entities with something to gain, ever determine the debate on this most personal and intimate decision. I’d think of that as ‘murder by algo’. “Who had something to gain?”, asked M. Hercule Poirot. (borrowing from Agatha Christie’s well known detective fiction)

Looking at it from another angle of the “we treat pets better than humans” notion:

I had a friend whose dog was SERIOUSLY ill, multiple terminal conditions, and in obvious, constant pain. On multiple meds. When I visited her and saw the agony her dog was going though, I cautiously asked if she’d considered having him euthanized. Her reply – “My vet keeps suggesting that, but I can’t do that because I would miss my dog SO much!!!!!”

I literally could never bring myself to be around this person again.

The argument that “family members could put pressure on their parents to partake of assisted-suicide” is balanced by (where assisted-suicide is legal) the argument that “family members could put pressure on their parents to stay alive, even if the parent is begging to die, because ‘We’d miss her SO much!!!’ “

Everything is case by case. Every animal’s and human’s situation is unique to them. There’s no one answer.

Our Covid bubble weekly potluck (6 of us, potlucking outside and 6 feet apart every Sat since October) was discussing this thorny topic last Sat.

One of us took care of his demented, paranoid, and combative nonegenarian father for six long years. Pater was a PITA for his son and the care workers who came in, fought everything and everyone, but son says he gave no sign of wanting to die and was always up for a walk.

Another is currently looking after a BFF who has pretty well lost her marbles and is incontinent, toothless, and very frail. OTOH, she is generally cheerful, has a good appetite, and can be quite good company. Friend says, “Kind of like having a 5 yr old who isn’t potty trained.”

Another has had bouts of severe depression and figures that if it hadn’t been so hard to suicide successfully, he probably would have taken that road out by now.

My own father was, at 96, was diagnosed with lung cancer, six months after his lady friend of 20-odd yeas, 91, had died. He opted for no treatment, lasted another 3 months which he used to put his affairs in order and transfer his house to my sister and her family, who are struggling financially in the rustbelt. The hospice-at-home visiting people were both nice and competent and my father availed himself of many of their services, but, “No, no, no guitar lady!”

My aunt’s husband left her at age 40 with two young sons. Two years later he was at the hospital for her 6-month checkup and the doc found what he though was a tumor, whisked her into surgery for a little look-see and found OMG. She died there within two weeks, they refused to let her go home to die, saying that the ambulance ride would kill her. She died, I am convinced, broken hearted. Another reason I don’t trust the medical establishment.

One of our potluckers has a long-time friend who was diagnosed with syringomyelia cyst between his shoulderblades, inoperable in his case, as, apparently, in most. The guy is in his 50’s, was a construction worker, and otherwise healthy as an outhouse rat. The cyst, which forms around the spinal cord but inside the spinal column, will continue to grow slowly, pressing on the his spinal cord. Since he is basically healthy, he is looking at years of pain, always increasing, then disability as the spinal cord is crushed. His brain will be the last thing to go. So far he is refusing painkillers or anything that will ‘fuzz his brain’.

Consensus was that if we really, really wanted to die, we should be able to make that decision and have it honored. Most vehemently, none of us was OK with someone else — an heir, a policy, an ethicist, the government, an algo, or, heaven forfend, an accountant — making that decision for us. But what if non compos mentis, or only temporarily ill or depressed? How would someone else either make or not carry out that decision when we can’t, or can’t express it, and how would we word executable instructions that would truly reflect our wishes? Cases vary so much. I firmly believe that my best resource in this life is my friends and neighbours. I would trust, for instance, a panel composed of our potluckers to second guess my wishes if I were not able, and fortunately this lady lives two blocks from me. I love this neighbourhood.

The crazy thing about the euthanasia debate is that people at risk of dying of Covid-19 are being sent home with no treatment at all because all pre-hospital treatments have been outlawed no matter the scientific evidence. Basically imho this is assisted death of people who do not want to die.

And the people who want to die due to terminal illness reasons are denied.

Basically, the people in charge are homo demens avarus

I used to be a psych RN. I saw all sorts of suicide attempts– you wouldn’t think it would be so tricky. We had a guy the staff caled ‘superman’ because he kept trying to fly out windows that just weren’t high enough. I’ve also seen lots of folks die horribly with zero pain meds. Nursing homes give nothing, and visiting hospice nurses only hand a lunch bag with a few ativan and bottle of morphine to the nurse, which many nursing homes seize and flush. Patient never sees it. My old GP had ovarian cancer and expects it will be back. Last time I saw her, she was pondering Helium as a suicide method. The bag over the head doesn’t do it for me! Maybe it’s possible to get ‘put down’ in Switzerland? It’s bad when one envies pets who receive better care.