I feel sorry for Mayberry v. KKR judge Phillip Shepherd. His record on this Kentucky Retirement System suit over abuses by hedge funds managed by KKR/Prisma, Blackstone, and PAAMCO shows him to be a careful jurist. He (hopefully supported by a clerk) will wind up having to consider the over 500 pages of objections to the Motion to Intervene made by the so-called Tier 3 Plaintiffs (ones in a mandatory “hybrid” pension plan) along with 60 pages provided by KRS and the Kentucky Attorney General, and the over 90 pages in two responses by the plaintiffs’ counsel.

But even with the overabundance of lawyering, there’s still a lot of educational and entertainment value in this case, in addition to its considerable importance if it ever gets out of stall speed. If the plaintiffs get to do discovery, they will expose the heretofore considerably hidden fees and costs paid by Kentucky Retirement Systems to funds that look designed to max out on looting: “fund of funds” with two layers of fees for dedicated, customized hedge funds. And they will also expose the limited partnership agreements, allowing for independent analysis of their almost-certain-to-be-one-sided agreements, based not just on our Document Trove but also CalPERS’ assessment at a private equity workshop it sponsored in 2015.

You can find all of the Motions of Opposition to the Tier 3 Plaintiffs Motion to Intervene (all dated March 2) at the Kentucky Pension Case site. We are embedding the three that provide the easiest access to the state of play: the Attorney General’s objection, and the two replies from the Plaintiffs: one to all the defendants’ arguments (there are 6 filings) and one to the Attorney General and KRS, the nominal defendant.

We’ll provide a background section for those new to the case or who might need a refresher; skip over it if you’ve been keeping tabs on this legal foodfight. In addition to providing a high-level recap of the arguments, we’ll focus on a central element of the case: the terms of the Tier 3 plan, at least as they can be inferred from the Kentucky Retirement System beneficiary materials. We hope counsel for the Tier 3 Plaintiffs will unpack for Judge Shepherd, since a major line of attack by the defendants is to misrepresent them. If the Tier 3 Plaintiffs are to prevail, they have to paper the record exhaustively as to how the Tier 3 plan works, since

One noteworthy feature of these filings is that they are regularly shrill, ranging from pissy to screechy (the Attorney General’s filing is a bit different in instead adopting the tone of royalty having to stoop to dismiss an annoying subject).

And the reason for the all too evident frustration among the various opponents is that the legal team targeting the hedge fund abuses was supposed to have gone away by now.

As the Background describes in more detail, they were supposed to be over after their initial case was dismissed by the Kentucky Supreme Court on standing grounds. Recall that the defeat came as a result of rulings in Kentucky and by the US Supreme Court that found that Federal Article 3 standing rules (which Kentucky has adopted but not other states such as California) means that defined benefit plan participants have to have suffered an actual (“particularlized”) loss, as in not be getting benefits or only be receiving reduced benefits, to be able to lodge a claim. Since the Kentucky Retirement System, even at its stunningly depleted 13% funding level, is still anticipated to pay out until 2027 (and we are supposed to believe the State of Kentucky will step up and make good on the pensions until it turns out otherwise), the defined benefit pensioners can take no action until then.

The case came back from the dead two ways, both big surprises. One was via the state Attorney General, Mitch McConnell protege Daniel Cameron, filing to intervene in the case. Note that the Attorney General could have done so at any point or joined the plaintiffs. All the fawning over the Attorney General by the various defendants confirms the charge made by the Tier 3 plaintiffs’ attorney in their filings, and that we made earlier: Mayberry v. KKR: Kentucky Attorney General Shows True Colors, Looks Over-Eager to Settle Pathbreaking Pension Case Rather Than Inconvenience Private Equity Kingpins Blackstone and KKR.

The second surprise plot twist was the legal team is still pursuing the case against the hedge funds, some of their principals like Steve Schwarzman of Blackstone, certain Kentucky officials, and key advisers, via the so-called Tier 3 beneficiaries. The Tier 3 group is in so-called hybrid plan, which is really the worst combination imaginable of defined contribution payouts and defined benefit lack of control. A well established body of ERISA rulings have held that beneficiaries in defined contribution plans have suffered when they experience a loss of or impairment to to their holdings. So the adverse Kentucky Supreme Court ruling on standing does not apply to them (although as we’ll explain below, the defendants try to argue otherwise).

The defendants and the Attorney General acted as if they could simply hand-wave away the Tier 3 claims of the Tier 3 group, as if they could and should be barred from court. For instance, in some of the initial scuffling over the Tier 3 intervention, both the Attorney General and some defendants tried to depict them as “non-parties” to the lawsuit as revived by Cameron.1

The opponents appear to have lost sight of the strong presumption in Kentucky law, that every wrong shall have a remedy. Judge Shepherd clearly agrees that the Tier 3 Plaintiffs have the right to plead their case.

Some of opposition’s other positions are equally high-handed. For instance, from the March 8 Reply Memorandum in Response to Defendants’ Opposition, embedded below:

In any court at any time, have any other defendants been so arrogant as to advance the argument they should be able to hand-pick who sues them?

The reactions of the opponents to the plaintiffs remind me of this scene from V for Vendetta:2

Background

In late December 2017, attorneys filed a derivative lawsuit for eight Kentucky Retirement System beneficiaries against three fund managers, KKR/Prisma, Blackstone, and PAAMCO, that had sold customized hedge fund products that contrary to their sales pitch, had high risk and underwhelming performance. The Kentucky Retirement System, at only 13% funded, is the most spectacularly underwater large pension fund in the US, despite Kentucky having some of the most stringent statutory fiduciary duty requirements in the US.

The fund managers allegedly focused on KRS and other desperate and clueless public pension funds who were unsuitable investors, particularly at the risk levels they were taking. KRS made what was a huge investment for a pension fund of its size. $1.2 billion across three funds all at once, in 2011, roughly 10% of its total assets at the time. They all had troublingly cute names. The KKR/Prisma funds was “Daniel Boone,” the Blackstone fund was “Henry Clay” and the PAAMCO fund, “Colonels”.

In the case of KKR/Prisma, the fund had installed an employee at KRS as well as having a KKR/Prisma executive sitting as a non-voting member of the KRS board. The filing argues that that contributed to KRS investing an additional $300 million into the worst performing hedge fund even as it was exiting other hedge funds.

The stakes here are much higher than the potentially meaty recoveries. Private equity and hedge funds fetishize secrecy because too often, their conduct will not stand up to scrutiny. The giant fund managers are almost certain to be most afraid of discovery, since they sharp practices they used with Kentucky Retirement Systems were very likely to have been replicated at other public pension funds. Even the limited discovery so far uncovered more misconduct and allowed the plaintiffs to add to their claims.

The initial case was appealed before discovery had gotten meaningfully underway, an unusual sequence of events. The plaintiffs lost on what most independent lawyers thought was an extremely strained ruling. The case then went to the Supreme Court, which dismissed the case without prejudice on standing due to intervening appellate and US Supreme Court decisions. The Supreme Court also got peculiarly snippy about private attorney pursuing these claims.

The Kentucky Attorney general, Mitch McConnell protege Daniel Cameron, filed a surprise Motion to Intervene on July 20. Bear in mind the attorney general’s office could have intervened at any time to support the case but oddly chose to now. Its filing was also clearly and wholly dependent on the earlier submissions by the private plaintiffs.

After a raft of oppositions, including multiple formulations by the somewhat reshuffled plaintiffs’ legal team (former lead counsel Anne Oldfather was replaced by her former co-counsel Michelle Lerach), Judge Shepherd issued an order on December 28. He rejected most of the plaintiffs’ reformulations to deal with the standing issues except having the so-called Tier 3 Plaintiffs effectively make their pitch. The reason the earlier case had been largely shot down was those intervening decision (such as Thole v. US Bank) required that the plaintiffs have suffered a “particularlized” loss. The Kentucky Retirement System beneficiaries hadn’t yet, since the fund has not yet missed a payment and arguably even if the system does, the State of Kentucky is also on the hook.

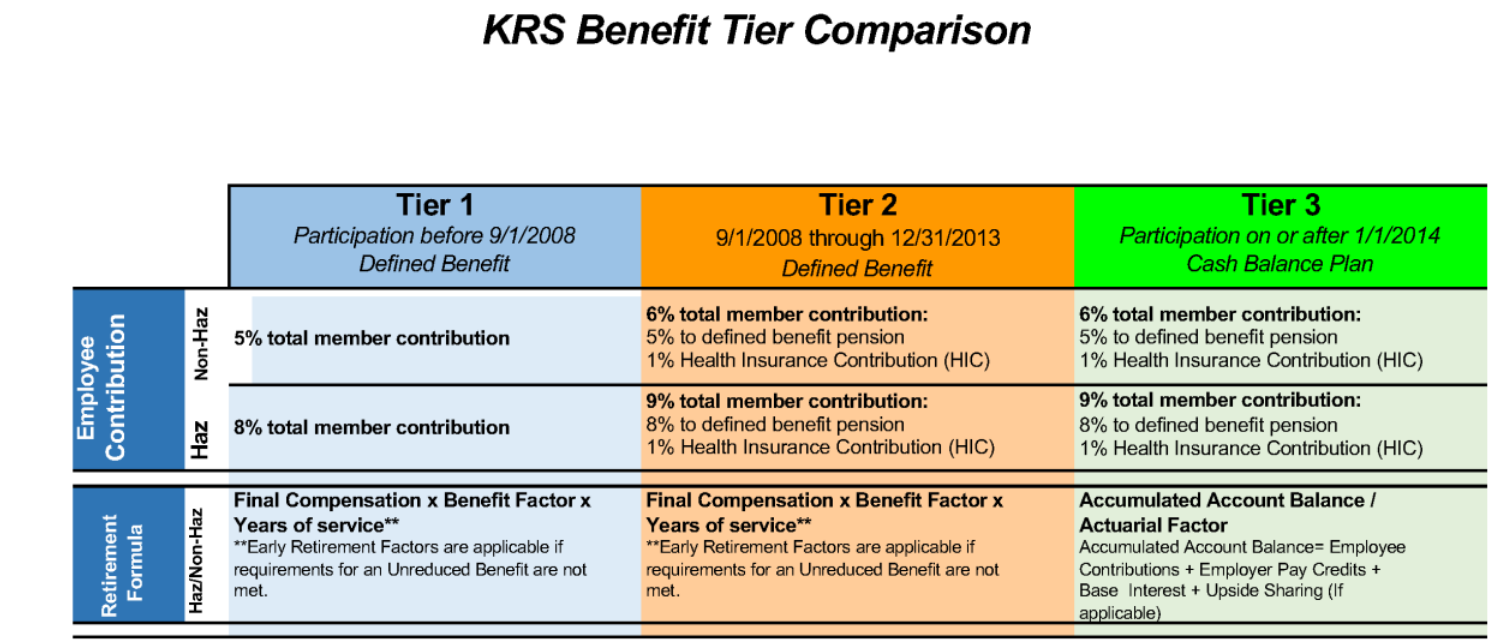

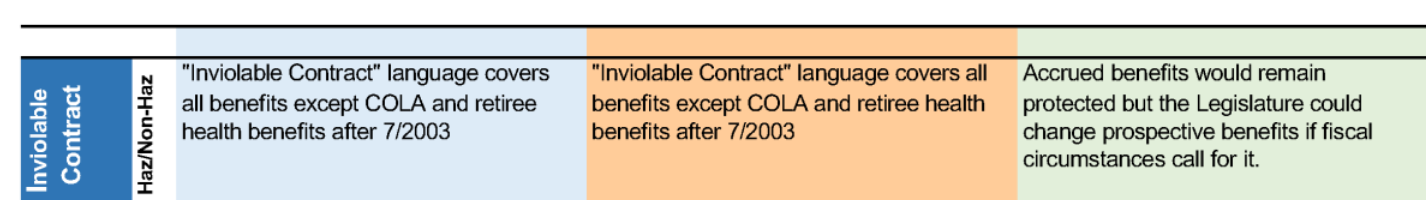

By contrast, the Tier 3 plaintiffs had mandatory deductions from their paychecks for a hybrid pension which is not state guaranteed. Even though public pension plans are not subject to ERISA, they are often managed in accordance with ERISA principles. The Kentucky Supreme Court in fact used ERISA cases to guide its decision. Unlike a defined benefits plan, which is what the Tier 1 and Tier 2 plaintiffs have, the Tier 3 plan is a defined contribution plan. Extensive case law backs the idea that under a defined contribution plan, the employee has suffered when his account balance is impaired. So the standard for loss is completely different than for the original “Mayberry Eight.”

The Defendants’ Arguments and How the Tier 3 Plan Works

Despite the considerable length of the documents, the plaintiffs’ lawyers contend, and it appears correctly, that virtually all of these issues were presented to the court in the original iteration of the case and Judge Shepherd ruled against the defendants. However, they weren’t as explicit as they might have been regarding either misrepresentations or misunderstandings about how the Tier 3 plan works.

The defendants are keen to depict the Tier 3 claims as dead on arrival because the Kentucky Supreme Court ordered the original case be dismissed on standing issues, that the plaintiffs had not suffered any “particularized” loss and supposedly never would because the State of Kentucky had made an “inviolate promise” to pay the pensions. The reason for focusing on the Tier 3 Plaintiffs is that they are in a “hybrid” plan. No matter what you call it, benefits are not fixed, not guaranteed by the state and depend how much the employee was required to contribute and how the pension fund performed. Hence the relevant precedents are for defined contribution plans. For instance, the US Supreme Court has found that lost profits are grounds for fiduciary duty suits.

While it would seem intuitively that a case based only on the Tier 3 plaintiffs, being only a subset of the beneficiaries, would not be able to garner as large damages as the original suit, as we’ll explain later, that may not true. This still looks like a potentially very juicy suit.

Not surprisingly, many of the defendants try to depict the Tier 3 filing as a dead letter, either simply asserting that the Kentucky Supreme Court order to dismiss the earlier case applies to the Tier 3 intervention, or getting to the same place by falsely depicting the Tier 3 plan as defined benefit scheme.

Another issue that the defendants talk up is the idea that the plaintiffs never sought redress from Kentucky Retirement Systems and their failure to have done that bars this case. Judge Shepherd had already ruled against this argument of failure to establish demand futility. The very short version is that derivative (or representative) cases occur when a company or government body fails to take legal action to seek redress for harm it has suffered. The plaintiffs ask the court to let them act derivatively, as in on behalf of the managers and/or board that is sitting on its hands.

For shareholder-related derivative cases, the plaintiffs have to establish “demand futility,” as in they tried to get the responsible parties to Do Something and they refused. In those cases, there are specific tests the plaintiffs must satisfy. However, Kentucky law does not require derivative/representative plaintiffs in pension cases to take that step. Again from the March 8 Reply Memorandum in Response to Defendants’ Opposition, embedded below (emphasis original):

A representative suit exists to protect the damaged, exploited entity (and its members) from the misconduct of those who control the entity and try to cover up or to conceal wrongdoing and protect themselves and other wrongdoers at the expense of the entity and its members….

In concluding that the OAG did not have the sole authority to represent KRS or to prosecute these claims, and that pre-suit demand was not required for this lawsuit, this Court noted that one must be cautious in analogizing the claims asserted by KRS plan members to traditional corporate derivative suits authorized by statute. They are not identical. Corporate type derivative suits take place within a statutory framework with explicit legislatively-imposed “gatekeeper rules”: pre-suit demand, security for costs, contemporaneous and/or minimum share ownership requirements, etc. Corporate shareholders are investors — they share in the profits and also losses of the enterprise. Their investment is portable — liquid — as they can sell, take their money and move on if they are hurt or dissatisfied. Not so with a KRS Member. Their pensions are immobile. They are “trapped” in the fund. Their financial, property interest in the funds are completely dependent on the Trustees obeying their stringent fiduciary and statutory duties.

Members of KRS can sue based on KRS § 61.645, as well as trust and common law — none of which has any statutory demand requirement.

The plaintiffs’ short overview of these and other defendant arguments (emphasis original):

According to Defendants—including KRS’s Investment, Actuary, and Fiduciary Advisors and the Hedge Fund Sellers, as well as their multi-billionaire owners, Schwarzman, Kravis and Roberts —the Tier 3 Plaintiffs’ Motion to Intervene should be denied because:

•it is untimely;

•it asserts time barred claims;

•the Tier 3 Plaintiffs failed to make a pre-suit demand to KRS;

•the Tier 3 Plaintiffs lack prudential standing;

•the Tier 3 Plaintiffs lack constitutional standing; and

•the Tier 3 Plaintiffs and their lawyers are a bunch of unethical troublemakers, who manipulated the legal system and ought to be run out of town.

All Defendants’ arguments are without merit.The Motion to Intervene is timely —filed on the date the Court directed (indeed, as Defendants also complain, too soon). The claims are not time-barred. They were brought years ago and found to be pleaded within the statute of limitations by the Court. The prudential standing of KRS members to sue under KRS §61.645, common law and trust law was also long ago upheld, when the Court rejected Defendants’ argument that only the OAG had standing to prosecute these claims.

This Court held that the original plaintiffs did not have to make demand on the KRS Board to sue. The Tier 3 Plaintiffs do not have to make demand now to continue that same lawsuit—whether by amendment or as intervenors.

The Tier 3 Plaintiffs have pleaded facts showing constitutional standing under a long line of federal appellate authoritiesunder the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (“ERISA”)—the new legal standard of standing for KRS members to suea dopted in Overstreet v. Mayberry … where the Kentucky Supreme Court…specifically reserved ruling on the constitutional standing of KRS Tier 3 members

The Attorney General’s Arguments

The Attorney General’s motion is imperious. It asserts that the Attorney General is authorized to take over the entire case. From his filing (emphasis original):

Not only does the Attorney General have standing, but he is entitled to take over this case and pursue those same claims. And because he has done so, the Attorney General has occupied the field. He has assumed control of the case and is pursuing the public interest in ensuring that KRS assets are managed in a prudent fashion, there is no room for the same claims to be somehow controlled or directed by a group of fund beneficiaries, their California consultant, and his legal assistants.3

The Tier 3 Plaintiffs point out that Kentucky Retirement Systems disagrees. They’ve retained their own counsel to analyze their claims and they’ll decide what if anything they will do then. Unlike most Kentucky government agencies, KRS has the power to hire its own lawyers without getting approval of the executive branch.

On top of that, they explain that the Attorney General appears not to understand the Tier 3 plan and therefore botches the standing argument.

Finally, the Attorney General can’t represent the beneficiaries because any damages he recovers goes to the State’s general fund. There is no assurance that any monies will go into KRS’ coffers.

And in case you missed it, here is why KRS, which once supported having the original “Mayberry 8″‘s legal team, is now pushing against them. From the Tier 3 Plaintiff’s combined Attorney General/KRS response (emphasis original):

KRS and the OAG suggest that we are beyond the pale in our discussion of various conflicts. But, they don’t actually refute the conflicts, and facts are pesky things.

Certain members of current and former KRS senior management —most particularly current Executive Director David Eager, who presumably is managing the $1.2 million investigation, and former Chief Investment Officer David Peden — committed serious breaches of duty as a result of conflicts of interest. One (but not the only) such conflict involved the wrongful conduct of these officials in essentially privatizing the management of KRS’s $1.6 billion hedge fund portfolio —placing management of the entire portfolio in the hands of a very self-interested KKR Prisma, effectively acting as inside director of hedge funds, without supervision by anyone other than Peden, himself a former Prisma employee — and expressly permitting KKR Prisma to self-deal with KRS trust assets in lieu of other payment for these “advisory services.” …

This situation pervades KRS’s new $1.2 million “investigation.” And, truth be told, much of the friction between KRS and this legal team can be tracedto our development of these allegations — taking the case where the facts led — and KRS’s months-long attempt to slow or stymie the development or public disclosure of this story.

While it is generally well known that Kentucky Retirement Systems is fabulously corrupt, identifying who stood to gain from particular crooked acts is quite another matter.

Why the Tier 3 Plaintiffs May Be Able to Extract Large Damages from the Hedgies

One might wonder why these high-powers lawyers are still fighting tooth and nail for what is now a subset of the Kentucky Retirement System beneficiaries, and almost certainly represent less than a third of total fund assets. Is is general cussedness? Sunk cost fallacy? A belief that getting at the total fees (many of which are hidden) and key documents will pave the way for similar suits?

Maybe. But it may also be that the Tier 3 suit has lots of economic potential.

Tier 3 is the worst possible combination of defined benefit and defined contribution features. All of those mandatory pension fund contributions go into the very same pool as the Tier 1 and Tier 2 defined benefit contributions.

The plan documents presumably have a lot more detail, but it’s reasonable to take the marketing materials at face value. These come from the Tier 3 Verified Complaint filed on January 7, 2021:

Notice that these different schemes are not described as separate plans but separate tiers in the same plan. Similarly, under “What is a Hybrid Cash Balance Plan?”

However, the assets of the plan remain in a single pool like a traditional defined benefits plan.

The reasons for believing that this single pool includes Tier 1, 2, and 3 assets as opposed to a separate pool for Tier 3 is the confusing language in the first section of the chart, which refers to “5% to defined benefit pension” when the payout is not a defined benefit, but a complex formula for each year’s performance used to calculate the total for each individual participant’s account.

The reason this matters is KRS is estimated to run entirely out of money in 2027. And if the surmise about Tier 1, 2 and 3 contributions all going into the same pot is correct, that mean that the Tier 3 beneficiaries are junior to Tier 1 and 2. In 2027, I would expect the Tier 1 and 2 investors to get whatever money was left in the pension pot on a pro-rata basis, with the state hopefully making up the shortfall. And unless KRS is able to pay 100% of the Tier 1 and Tier 2 benefits in that final year, I expect the Tier 3 beneficiaries to get nothing.

To put it another way, the Tier 3 beneficiaries are effectively in a “first loss” position.

That further means that Tier 3 Plaintiffs can argue that the hedge fund fees and costs and underperformance effectively come ENTIRELY out of their hide. That in combination with the lack of a state guarantee would appear to strengthen the case for damages: that the risk to them in imminent, in pension timescales, and the impact will be catastrophic. Any meaningful recoveries, even if they have to go to all tiers, will make the biggest difference to them.

That means the plaintiffs’ attorneys can argue for the same level of damages as in the original filing despite representing a vastly smaller total economic interest in the fund. If the defendants believe that too, no wonder they are seeing red.

A party familiar with this case concurred with this analysis, but further input very much welcomed.

Regardless, Mayberry v. KKR continues to be an intriguing case. And like Judge Shepherd, I’d like to see it proceed.

____

1 This position wasn’t about procedural issue of the Tier 3 Plaintiffs using a Motion to Intervene to get in court; they’ve also filed a stand-alone backstop motion. It very much read as if the Attorney General was saying that he was not interested in representing the Tier 3 Plaintiffs, and therefore they had no business showing up in court.

2 A pet peeve about this film: it never explains V’s strength and speed. The graphic novel does. V was one of the very few survivors of biological experiments at Larkhill. They damaged his memories but enhanced his physical abilities.

3 This is a gratuitous insult to Michelle Lerach, who is a very accomplished attorney. The Attorney General is smearing her as being a cat’s paw of her husband, the “California consultant” Bill Lerach. I hope Michelle Lerach has the opportunity to show the smug Attorney General Cameron, who had never litigated a case, that he has a lot to learn.

00 AGs+Opposition+to+Tier+3+PlaintiffsMotion+to+Intervene

00 ReplyreMotion-Intervene-KRS-OAG

“The opponents appear to have lost sight of the strong presumption in Kentucky law, that every wrong shall have a remedy.”

I know that there are no shortages of lawyers involved in this case going by the descriptions here but did that little nugget on info slip past most of them? Or did they think that Kentucky would just let it go by? In fact, I would say this-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-nPl-qAkUO0

Thanks for this nice summary of the case and the legal jousting to date. I’ve been following this case in NC’s links but, to be honest I don’t think I fully understood how all the parties related. This pulled it all together for me.

Judge Shepherd is awesome! Easily the smartest and most rational judge in the state. He’s become a regular victim of KY Republican vitriol, though he has a long record of unbiased rulings. They hate him so much because he is one of two judges on the Franklin County circuit court where all lawsuits against the Commonwealth must be filed. With a supermajority in both houses they set about extracting their thorn during this legislative session, passing a law that will now spread those suits over the entire state (I forget if it’s random or has the judges in a rotation). They moved as close to explicit judge shopping as they possibly could with a Democrat in the governor’s office.

Very much appreciated the piece.

Look what has happened to the US since they got confused between making money and creating wealth.

When you equate making money with creating wealth, people try and make money in the easiest way possible, which doesn’t actually create any wealth.

In 1984, for the first time in American history, “unearned” income exceeded “earned” income.

The American have lost sight of what real wealth creation is, and are just focussed on making money.

You might as well do that in the easiest way possible.

It looks like a parasitic, rentier capitalism because that is what it is.

You’ve just got to sniff out the easy money.

All that hard work involved in setting up a company yourself, and building it up.

Why bother?

Asset strip firms other people have built up, that’s easy money.

The private equity firms have found an easy way to make money that doesn’t actually create any wealth.

Private equity firms ransack their economy and they think it’s good because they make lots of money.

Bankers make the most money when they are driving your economy into a financial crisis.

They will load your economy up with their debt products until you get a financial crisis.

On a BBC documentary, comparing 1929 to 2008, it said the last time US bankers made as much money as they did before 2008 was in the 1920s.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

At 18 mins.

The bankers loaded the US economy up with their debt products until they got financial crises in 1929 and 2008.

As you head towards the financial crisis, the economy booms due to the money creation of bank loans.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

The financial crisis appears to come out of a clear blue sky when you use an economics that doesn’t consider debt, like neoclassical economics.

Wall Street’s lobbyists aren’t doing them any favours.

What’s good for bankers isn’t good for the US, but they haven’t worked it out yet.

Neoclassical economics is a pseudo economics that hides the inconvenient truths discovered by the classical economists.

The classical economists identified the constructive “earned” income and the parasitic “unearned” income.

Most of the people at the top lived off the parasitic “unearned” income and they now had a big problem.

This problem was solved with neoclassical economics, which hides this distinction.

It confuses making money and creating wealth so all rich people look good.

If you know what real wealth creation is, you will realise many at the top don’t create any wealth.

The neoliberals picked up this pseudo economics and thought it was the real deal.

Things were never going to go well (see above)

It sounds like the Kentucky AG is flailing. He’s gonna lose his argument that the 3rd tier has no standing or has misfiled its motion, etc. And when the 3rd tier wins (which all the facts point to) then they are last in line to be made whole, right after tiers 1 and 2 beneficiaries. Which guarantees a big settlement. So that’s nice. The question I have is how can the hedgies save their own bacon – what twisty thing will they try next? And if some ruling comes down that lets them off the hook will it be from far above, say Mitch’s office? How corrupt is the fabric of the whole system? I do like the thought that Mitch is truly sick over this. Or any other pol who has facilitated the rape of so many state retirement funds. Like the ones that are trying to throw CalPERS to the dogs. And then of course the big question: how do we all admit that 8% returns are pure lunacy (if not malicious nonsense) in a world desperate for sustainability?

This reminds me of why I quit law school after one year and gave up my draft deferment in 1967. Anything is better than reading and writing briefs.

Maybe public pension plans once made sense. But now with everyone having access to 401Ks, Roth, Keough, etc they make little sense. Like all public property controlled by government organizations, the pension plans slowly turn into pools of money that the well-connected can take a share of when no one is minding the store… which is most of the time.

But to wind up the old pension plans and move future retirees to 401s would require an accounting and the admission that “Gee, we don’t have any money to pay you”. Welcome to the U.S. Postal Service pension debarcle. The virtuous circle of unions, legislators, CPA firms and managers that benefit are essentaiily parasites we don’t need. And while we’re at it the government pension system and the lush garden of cushions for Congress should go away too.

I’m wishing but I’m under no illusions… too many of the well-connected benefit from the present system.

We’re much better off having a more generous Social Security system than private pensions. Forcing eventual retirees to seek returns in the market promotes financialization, which is economically destructive. Secondary market trading, beyond a low enough level to achieve price discovery for new corporate fundraising, diverts resources into unproductive activity. You are now twice as likely to become a billionaire by being an asset manager as being in tech. How much sense does that make?

On top of that, forcing people to invest to retire requires that financial assets deliver returns in excess of GDP growth. That can’t happen on a large-scale basis (trees don’t grow to the sky, financial assets can’t eat all the value of GDP, which is where you get with sustained higher returns) without periodic financial crises to reset financial asset prices. Oh, and what happens to those investors then?