Yves here. In addition to showcasing Hubert Horan’s epic Uber series, we’ve also taken a harsh look at venture capital, and most of all the unicorn hype, more broadly. For instance, we warned in 2017: Fake Unicorns: Study Finds Average 49% Valuation Overstatement; Over Half Lose “Unicorn” Status When Corrected.

We have to confess to being old enough to remember the dot-com, and then the dot-bomb era. While that frothy period did produce some durable enterprises, it also featured inanities like Boo.com and the Time Warner-AOL deal.

And CalPERS really ought to thank us. Remember that the giant pension fund was over-eager to launch its “private equity new business model” which included “late stage venture capital” as one of its “four pillars”. That meant late-stage unicorns, given CalPERS’ need to deploy lots of capital. Our continued prodding of the too many internal contradictions, along with CalPERS’ eagerness to pile onto fads past their sell by dates, led the initiative to be quietly abandoned. The press today announced its official death. Per the Wall Street Journal: Calpers Steps Back From Four Pillars Strategy.

By Jeffrey Funk, and a professor for most of his life, most recently at the National University of Singapore. You can follow him on LinkedIn A much longer version was just published in American Affairs. Originally published at Wolf Street

About 90% of America’s Unicorn startups, ones privately valued at $1 Billion or more, were losing money in 2019 or 2020. According to my recent article in American Affairs, only 6 of 73 were profitable in 2019 and 7 of 69 in the first two or three quarters of 2020 despite most being founded more than 10 years ago.

The six profitable start-ups in 2019 included three fintech (GreenSky, Oportun, and Square) and one startup each in e-commerce (Etsy), video communications (Zoom), and solar energy installation (Sunrun). For the first few quarters of 2020, three of these firms became unprofitable (Oportun, Square, and Sunrun), and four others became profitable: three e-commerce companies (Peloton, Purple Innovation, and Wayfair) and one cloud storage service (Dropbox).

Unicorn startups are even more unprofitable than those that did not achieve Unicorn status. According to Jay Ritter, about 20% of startups at IPO time were profitable over last four years, much more than the 10% of Unicorn startups in 2019 and 2020. Thus, not only has profitability dramatically dropped over the last 40 years among those startup doing IPOs that went public, down from 80% to 90% in early 1980s, today’s most valuable startups—those valued at $1 billion or more before their IPOs—are in fact less profitable than startups that did not achieve $1 Billion in their IPO valuations.

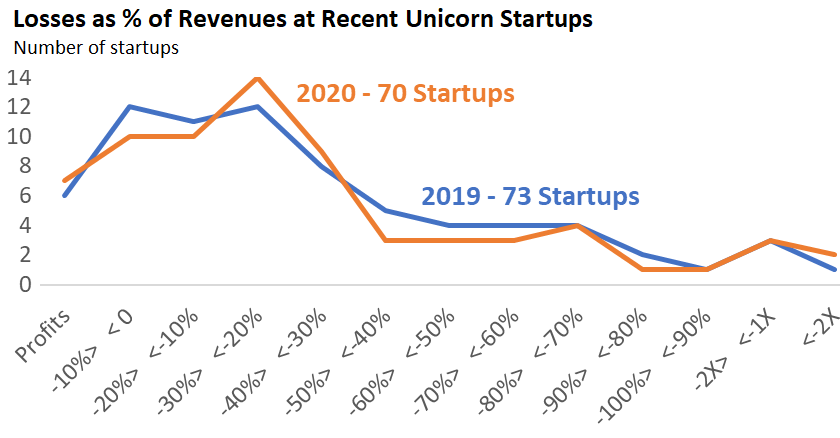

Even worse, a remarkably large fraction of start-unicorns have high levels of unprofitability, as shown in the chart below.

- In 2019, 21 of 73 had losses greater than 50% of revenues, and another 13 (including Uber, Lyft, Pinterest, and Snapchat) had losses greater than 30% of revenues (not counting liquidations).

- In 2020, 19 of 70 had losses greater than 50% of revenues, and another 11 eleven had losses greater than 30% of revenues.

Source: Jeffrey Funk, The Crisis of Venture Capital: Fixing America’s Broken Start-up System, American Affairs,

These high annual losses have also translated into large cumulative losses for some startups, much larger than Amazon’s peak of $3 billion twenty years ago. Uber has more than $30 billion in cumulative losses; and Lyft, Snap, and Palantir have more than $5 billion each in cumulative losses.

How Many of These Startups Might Become Profitable in the Near Future?

One way to address this question is by looking at the changes in profitability during 2020, a year in which some Unicorn startups benefited from the lockdown and the higher revenues and willingness to pay that these lockdowns brought. Cloud computing services, food delivery, e-commerce, and Internet entertainment benefited from the lockdown enabling people to work, shop and amuse themselves while stuck in their homes.

Consider the 59 Unicorn startups for which full 2020 income results are now available. Twenty-six had higher ratios of income to revenues, 29 had lower, and four about the same, despite most achieving more than a 30% increase in revenues and some more than 100% in 2020 than in 2019. This simple counting suggests that overall, we shouldn’t expect a vast change in profitability in the near future.

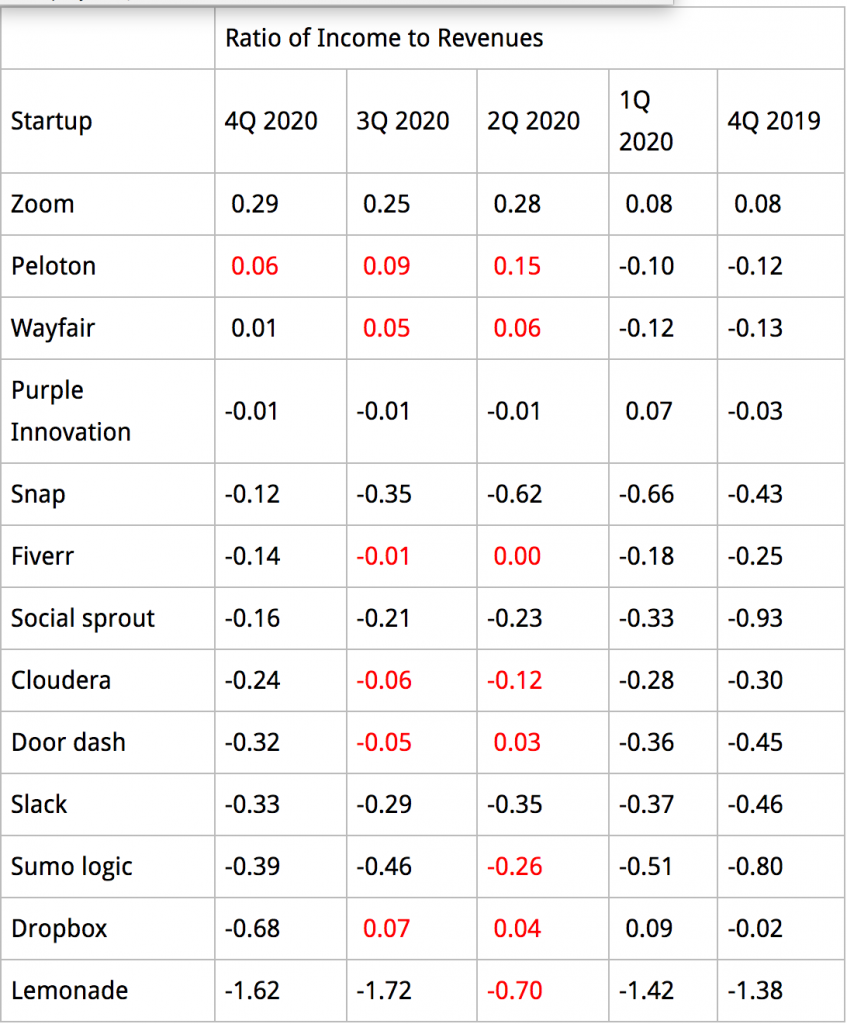

Looking in more detail, consider those startups that went from unprofitable in 2019 to profitable in 2020 or that achieved an increase of at least 0.20 in their ratios of income to revenues between the two years. These startups are listed in the table below, along with their quarterly income since the fourth quarter of 2019.

If a startup is making progress towards profitability, we would expect them to show continuous increases in their ratios of income to revenues, and not just a one or two quarter improvement during the most severe months of the lockdown, when people were willing to pay almost anything for food, cloud computing, mattresses, exercise bikes, and other products and services.

The table below shows that most startups achieved one or two quarters in increases (figures highlighted in red), and not a series of increases that would suggest strong trends toward profitability.

Lemonade, Sumo Logic, Cloudera, Door Dash, Dropbox, and Fiverr are the most conspicuous with big reductions in losses for the second and/or third quarters of 2020, but then increases in the fourth quarter. Somewhat better, Peloton and Wafair show a bigger trend towards profitability but still declining results in the last one or two quarters of 2020.

A lack of continuous improvement in profitability throughout 2020 suggests that the ratio of losses to revenues for these startups may not improve once the lockdowns are over and ratios for some startups may even worsen.

Table: Recent Profitability for Selected Unicorn Startups (Improvements in Red)

The best results, showing continuous improvements in ratios of income to revenues, can be seen for Zoom, Purple Innovation, Snap, Fiverr, and Social Sprout. Zoom is clearly far ahead of the others with rising profits while Purple Innovation’s improvements in profitability are much more modest. The others experienced improvements in profitability, but they still have losses greater than 10% of revenues.

The best results, showing continuous improvements in ratios of income to revenues, can be seen for Zoom, Purple Innovation, Snap, Fiverr, and Social Sprout. Zoom is clearly far ahead of the others with rising profits while Purple Innovation’s improvements in profitability are much more modest. The others experienced improvements in profitability, but they still have losses greater than 10% of revenues.

Overall, these data suggest that most Unicorn startups will struggle to achieve profitability in the future and thus the small percentage of Unicorn startups currently profitable (about 10%) presented at the beginning of the article, will probably not change much in the near future. The percent profitable may rise to 15% or 20%, but not much higher without dramatic changes in technology or scale.

The startups that were profitable in 2019 but went unprofitable in 2020 (Oportun, Square, and Sunrun) may return to profitability, but some of those who became profitable in the first two or three quarters of 2020 (Peloton, Purple Innovation, Wayfair, Dropbox) may become unprofitable after the lockdowns end. Those experiencing continuous reductions in ratios of losses to revenues such as Snap and Social Sprout may also achieve profitability in the near future.

Hmm. I have an issu with the study, which is using “profitability”.

That’s not because I’d think there’s all well in the unicorn land, but because the author selects to joust on the startup’s battlefield, which is bad. A simple rejoinder to the “profitability” become “we’re investing, so we can’t be profitable!”. Which is usually hard to disapprove from simple revenues/profitability numbers.

A better measure is free-cashflow. If a company has a billion valuation, but no free cashflow, then it’s basically burning through cash, and one has to look deeper to see whether it can ever be profitable (cf Uber, which can’t because the fixed costs scale with revenue – but that needs a deeper analysis).

If it has free cashflows, then a company can be fundamentally profitable even if it’s not profitable on paper.

I don’t believe Uber had free cashflows ever (excluding one-off gains from selling stuff).

There are still subtleties you need to take into account (constant investment will eat into free cashflow too), but IMO it’s still much better than looking at accounting profitability.

Agreed, if for nothing else but to counter the well worn “we are reinvesting in growth” retort favoured by startup founders when asked about profitability. Although it can be a double edged sword, I would add operating leverage as key metric to a deeper level analysis of a company’s prospects.

I’m tempted to say it was ever thus – from railroads in the 19th Century to the overinvestment in internet at the turn of the millenium, investors have been happy to fund speculative investments. The likes of Amazon and Facebook together with a surfeit of capital seem to be setting the tone: the important thing is growth, which will allow profits to come along in due course. Profit metrics are not what investors are looking at for these companies.

I think the really interesting analysis would be unit economics. If a company could turn off growth and become profitable, then there is probably some value, whereas you have to worry about a company that can’t do that. Hubert Horan’s analysis of Uber, rightly, emphasises this point. I think there will be casualties in this group, but survivors too.

Here’s the thing that bopped me over the head: The businesses that so many of these companies are in. I mean, come on. Are they competing for the Stupid Prize?

Like a startup for exercise bikes? Delivering food to your doorstep? Driving people from hither to yon?

IMHO, they deserve laughter and derision, not money.

Arizona Slim: Well observed. Most of what these companies offer is either too-too disposable income or distribution. It seems to me that in the U S of A, many vaunted “industries” are refinements to the distribution system: Railroads, Federal Express (which is in fact a skim off the bailiwick of the post office), Amazon, and the various food-delivery scam/platforms.

I happen to like Etsy, and I note that Etsy is among the “profitable.” What matters about Etsy is that it is a cataloguer of small shops. The Etsy shopowners make things. I have used Etsy more than usual during the pandemic, even ordering some clothes for myself, and Etsy and its shopowners work everytime.

Etsy is set up to be a far cry from the usual click-though-twelve-menus-into-oblivion.

In my not so humble opinion, Etsy is one of main examples of WWW success–at my job, I sometimes brought discussions of e-offerings and e-platforms to a screeching halt by mentioning how well Etsy works. Among the serious people, Etsy is not serious use of bandwidth.

Yet, like pornography on the WWW, Etsy flourishes. Who’da thunkit?

One of my neighbors has an Etsy shop for his fine art and illustration. Been meaning to ask him how it’s working. I’m tempted to try the same thing.

Etsy works quite well for my wife and many others doing things like custom jewelry or vintage couture. The real difficulty is that once it hits a certain critical mass of economy of scale, like EBay, it will begin to abuse its constituent ‘creators’. Try getting help for an issue on Ebay or Paypal. It’s much easier getting through to a human at the DMV. Success brings arrogance.

I don’t know about your first or third example, but the investment promise of food delivery is rather clear. The goal is not to become a food delivery company, but to become the sole middleman between delivery restaurants and customers. At that point, you can squeeze out a good chunk of the gross revenue of the restaurants, mostly as pure profits for you. Look at booking.com for a similar scam that is already paying out fortunes (to its owners) in the hotel business.

The actual delivery part is only a strategy to achieve that position. Other companies (like takeaway.com in europe) are aiming at the same middleman monopoly while keeping the delivery at the restaurants themselves. Perhaps there will never be a middleman monopoly in the food delivery business . But investors think that there is good chance of one, and they are paying for that chance. I am afraid they might be right on that.

That’s basically the premise of silicon valley – software tends to become monopolistic, most business will have some software-run part in their supply chain, the monopolistic owner of that software can lap up most of the profits from the business, while the rest of the supply chain competes for the leftovers.

It doesn’t work always, but it works rather too often, so it attracts investment money. The alternative is investing in those other parts of the supply chains, and risk getting Nokiaed.

I’m sorry, this is just silly.

There are no barriers to entry in food delivery.

And there is no skill required to build a delivery app.

I agree that it looks silly, but that doesn’t mean it can’t work. The same argument would make Booking/Priceline silly. It shouldn’t be hard to build competing websites or apps – and there are plenty, obviously. They still made a profit of 5 billion dollar in 2019, and even some billions in 2020, corona and all.

Restaurants can run their own ordering website for very little money. You don’t even need much technical skill. Plenty of tiny ones have some off-the-shelf system that works fine. But despite that, the platforms are still raking in billions in revenue from those same restaurants. Grubhub and Takeaway are not (yet?) massively profitable like Booking, but they are not massively losing money on Uber-style subsidies either. Restaurants don’t want to hand over most of their margin, but they do anyway.

I find this all crazy and I would not gamble my money on it. But the craziness gets fueled by examples that do make absurd profits.

No, they aren’t even remotely similar.

Airline inventories require massively complex software. That’s why American was able to monetize its Sabre System. They are huge, real time databases. The companies have to cut deals with Big Companies, which means big lawyering. And they come close to having the FedEx problem, of having to have a very large critical mass at the get go to have the reach to appeal to users.

Food delivery is local. Any bloody restaurant can deliver its own food if it wants to. See many Chinese restaurants and pizzerias. And Fresh Direct and many grocers too.

Many customers prefer to pick up due to certainty of getting food as close to prep time as possible.

The software is vastly simpler and there are no to at most weak scale advantages.

Many restaurants in Italy (where I am blocked in my Covid bubble), use WhatsApp for orders. There is no need for expensive apps, website development, domains or software maintainance. Restaurants that do not have websites will email (or whatsapp you) a menu on request, and all you need to do is message your order back with the desired pickup (or delivery) time. No technical skill needed. IMHO , these “middleman” delivery apps are pure money-sucking scams that do no service to restaurants, customers or their employees.

I fully agree on the money-sucking part. Around here, I see many restaurants who have their own working website where you can order (you can hire these for very little money), or indeed rely on phone or texting etc. But most of these restaurants are also on the platforms, if that’s where the customers are.

The platforms are not primarily offering a technical service (be it the website or the delivery). They also do that, but that’s not where they hope to get rich. Exactly because that space is too competitive, and too easily replaced by something cheaper.

What they are offering is a marketing platform, a flow of potential customers. To a large extent, they pull customers away from other means to discover restaurants, then sell them back to those restaurants for a cut of the take. I doubt that it’s socially useful, and surely not in proportion to their take. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be profitable.

As an analogy: the platforms are building the online equivalent of a busy area, where restaurants pay a premium so they can attract passer-bys.

Restaurants don’t have to be in the busy area. Some restaurants do perfectly well in a backstreet, with customers who know where to find them. Such customers will also find their website or WhatsApp.

But for most restaurants, location is important. They pay high rents for that. The delivery platforms want to be the online equivalent of a premium location landlord .

Apologies if I’m repeating ground covered elsewhere.

It may be silly, but that’s the entire premise of these platforms – for example Deliveroo in the UK. I’ve not looked at any of the American players, but I’m fairly sure the business model is the same.

Looking at the upcoming Deliveroo IPO they’re clear that they want to be the first place consumers turn to when they think about food – whether it’s delivery, groceries, pickup or ordering in a restaurant. An addressable market of £1.2 trillion, apparently.

Much like Uber, they’re burning through cash at a terrifying rate to try and achieve a monopoly position while simultaneously not acknowledging their riders as employees to cut costs. At this point, it’s effectively an investor subsidy for getting food delivered.

Deliveroo is a logistics business masquerading as a tech company. They’re banking on “moats”, “network effects” and “economies of scale” to create a monopoly when, in reality, they don’t have a defensible position as there are no real barriers to entry and their only real asset is their rider base and the restaurants – both of whom can and will move between platforms.

Deliveroo couldn’t make a profit in 2020 with the boost from Covid-19, and in fact nearly ran out of cash and had to use the failing firm defence to secure a bail-out by Amazon. It’s hard to see how the investable proposition is anything but ride the growth and leave someone else holding the bag during the crash.

I only used Doordash once during 2020. We used local delivery services for the rest of our deliveries. We try to tip $5 cash minimum, handing the bill directly to the courier.

Many of these restaurants are small, but still have managed to piece together their own cart systems and interface with smaller couriers. The barriers are pretty dang low if a burrito truck can manage to get this done competently.

They are losing money. There is no path to profit.

The fact that there are greater fools does not make a business case. Did you miss my reference to all the dot bomb companies?

I agree, completely.

Deliveroo has no plan to get to profitability with the company as is and, given the growing likelihood they’ll have to actually pay riders properly, their largest cost can only increase. As far as I can tell the only real difference between Deliveroo and Uber / WeWork is the order of magnitude of the losses they’re accumulating.

I did miss that reference at the start, and some of us aren’t old enough to remember that crash to draw parallels.

It’s just the dot.com phenomenon with life squeezed out of it due to smart phones and too much money in the hands of the 1% who can afford to wait for a big score. People bought books before Amazon. Bulletin boards existed.

Functionally, we are at a point where we have squeezed every drop of innovation from the microchip without government infrastructure changes. The smart phones wouldn’t be possible without the ’96 telecommunications act. Remember when we stopped having television antennas on our houses?

We are in the Era of novelty and Pet Rock crazes because that is all the little inventor can make on their own.

I have a TV antenna which I installed. I refuse to pay for content which carries advertising.

I’ve also met a rogue cable content supplier. One up front payment, and no more bills.

A rogue cable content supplier sounds interesting. I remember the black market cable boxes back when the communication was just one-way. You paid a couple hundred bucks once for the box and you got every single channel, including all the premium channels and premium events. These were never that common in my area but they were around – a friend had one and we watched one of the over-hyped Mike Tyson fights back when I used to care about such things.

The only thing one had to worry about back then was the cable company sending out a signal which might fry the box, but that seemed to be more rumor than reality. But I thought “cable theft” ended with the advent of more advanced two-way communication between the box at home and the cable company?

Alas, the dotcom era obsession with exponential user growth sans a clear path to profitability casts a long forward shadow. The Nasdaq and the ecosystem around it (e.g. analysts) are still ideologically wedded to this “growth story” of high burn rates to drive up user numbers, and the whole thing as currently set up rewards top line growth much more than sustainable growth in bottom line earnings. Sure, there are token concerns about lack of profitability in analysts’ reports about these unicorns but “buy or hold” recommendations froor their various stocks still abound, meaning the public markets aren’t sufficiently punishing this state of affairs to force a change in direction. Until that happens, expect none of this to change.

“Buy or hold recommendations for their various stocks”

Uhhh…is there such a thing as ‘start-up’ and profit? I don’t think so. It usually takes approx. 5 years or longer. But I’m old school.

A business is usually ‘tweaking’ and still purchasing necessities to refine their ‘well-oiled machine’ are they not? These things take time.

The prof teaches in Singapore? Curious.

Maybe he now knows why alot of tech secrets and intellectual property is stolen by Asian govts. It’s easier to steal than to start-up.

Christy: Did you try getting through the first paragraph? Here’s what the perfessor adds as a condition:

despite most being founded more than 10 years ago.

Christy is obviously a business expert as well as an international relations savant-

alot of tech secrets and intellectual property is stolen

because no one can stop them…it’s certainly the mantra of all of our glorious disrupters…

What christy calls stealing silly con valley calls innovation.

sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander and all…

‘The prof teaches in Singapore? Curious.’

Not sure why the snark here. And he taught in Singapore but is now retired from there. It could be that with articles such as this one that he may not be welcomed on a lot of western campuses as it is too close to a reality check. A cardinal sin that telling the truth in a uni setting.

As for choosing Singapore, if I had a job like his I would love to locate to a setting like that to work in a different cultural setting and exploring different viewpoints of the people that live there. And I can only imagine what the foods must be like there so what’s not to like?

In a way this article misses the point.

The VC business is predicated on a “play-it-forward” strategy. The VCs make money by AUM and rising valuations. So when they look at a potential investment they are really asking the question can I earn a fee/carried interest in the next round(s). I am not making a judgement as to whether this is how it should be, but my experience on how it is.

Also, having dealt with them from both sides of the table over the last 20 years, they want very high IRRs and no risks — which is counter what they say.

So, if you accept my view of their business model then what is broken is the valuation processes that support them and as flagged on NC a faulty world that raises the valuation for the enterprise based on the most recent round without consideration to the different structures of each round.

I would add that in the 90s I was a PM at one of the largest institutional asset managers in the world. As we could invest a limited amount in non-public companies I was given the assignment by the Head of Investments of vetting these. The question I always asked management was “in 25 words or less what is your value proposition to customers and my job is to figure out if they could make money doing this?” Too often the answer was “…we have a website with all these pages.” I don’t think they actually understood. I would point out that if Amazon could sell the same book as Barnes & Noble for 30% less or Schwab could execute the same stock trade for $69.95 that Merril charges $300 for that is an economic value proposition. In my opinion most of the businesses above cannot articulate a value proposition.

VCs aren’t in the business of a steady stream of dividend income, they’re after the big EXIT, to this end they’ll shovel insane amounts of capital to founders to build a startup that looks good on an IPO prospectus, or to a potential acquirer. The most recent example, Slack, was a big pay day for its investors after being acquired by Salesforce, endowing said investors with the kind of cachet that’ll make raising their next fund a breeze.

The policy justification for allowing ERISA investors to invest in VC (and public pension funds hew to ERISA even though not subject to it) was to promote valuable enterprises, not create trading sardines.

Sunrun’s 2019 was saved by the CA wildfires, the associated power outages, and their somewhat coincidental deployment of Tesla Powerwalls. They had huge sales gains in CA because they could not only sell you your own generation capacity, they could sell you battery backup for the whole house, which was a really appealing selling point if you live in CA. 2020 brought the pandemic and most of their sales channels evaporated (they do a lot of business selling through Home Depot and Costco, and they couldn’t deploy sales agents to those places for quite a while, last I saw they still hadn’t returned to Costco).

So that pretty neatly maps to what happened to them 2019-2020. Their stock made a big runup in late 2020 due to the Vivint Solar acquisition, I don’t know if Vivint has a more robust sales model. They’ve given back a lot of those gains, so maybe the sales aren’t rebounding like the market thought. I know Sunrun was pretty active in TX, so maybe there will be some demand for the solar + battery solution there, given the recent blowup of the electric market there, although TX does not offer incentives or power buyback rules the way some other states do.

Tesla Powerwalls & Solar panels – what’s their life expectancy? I’d really like to see how often on has to replace the Powerwall and associated panels for a new model, and compare the relative costs of Grid and Solar + Storage.

If you do have that supplier, don’t buy an electric car. There are hard limitation on the supply of electricity. Limitations which do not exist with grid power.

If it isn’t broken, don’t fix it applies.

Our solar panels, made in WA (final assembly only, probably) have a 25-year warranty.

I can’t help thinking we haven’t learned much since the Financial Crisis of 2007 – 2008. During this last financial crisis, massive losses were created when investors poured imprudent and highly leveraged sums into mortgage backed securities that were filled with questionable consumer loans. These consumer loans were called ‘subprime’, and many were questionable because underwriting deteriorated to the degree that many borrowers had No Income, No Job, No Assets (colloquially called “NINJA” loans).

It seems we now have a situation where imprudent sums have been poured into questionable ‘unicorn’ investments via venture capital, IPO’s, equities, leveraged loans, and high yield bonds. Many of these investments are questionable because the corporations backing them have Negative Income with no path to profitability, No Governance, and (almost) no Physical Assets to liquidate in bankruptcy (what you could colloquially call “NINGPA” investments). This is essentially the same greater fools game that was played with housing prices before the 2007 crash.

So similar playbook to 2007 – 2008 Financial crisis, except what backs these investments has switched from consumer to corporate obligations.

This might seem like I’m stating the obvious but any company that constantly generates massive losses, and has virtually no assets will not be able to pay back its investors.

> but any company that constantly generates massive losses, and has virtually no assets will not be able to pay back its investors.

Uber has gone from law breaker to law maker while accumulating losses of $30+ billion. Investors are being rewarded handsomely already.

Big Money = Big Speech

BrianM, above, aptly compared the post-1985 boom to the railroad boom of the 19th Century.

The rail boom was driven by technical innovations (the efficient tube boiler gave us river steamers and railroad engines and the Bessemer process gave us cheaper, more predictable steel rails). The obvious need to move bulky, low-value products and people long distances created the need. Hundreds of new railroads sprang up and many were instantly profitable, which drew in entrepreneurs and innovators who perfected everything from the telegraph signal system to the air brake, all of which drove down prices and improved profits. Then the consolidators moved in. The best book on the subject is “Railroads Triumphant” by Martin (Oxford Press, 1992) and reading it gives real insights into the post-1985 boom.

And that boom was also driven by unexpected technological innovations: the microchip; the Southern Pacific’s microwave towers relaying data from LA to NASA Houston which turned into Sprint, the fiber optic cable and, more important, the fiber optic repeater); the tinkering technical innovators at Sun, Apple. Huge almost instant profits followed, all made possible in part by Judge Geneen’s court-ordered breakup of ATT in 1976-7 and the telecommunications act of 1995.

Let’s not forget that 1/3 of the bandwidth and more than half the profits of the early internet were from semi-legal porn, all of which was made safe in 1992 by Hillary Clinton who told the Justice Department “We are no longer in the porn-busting business” at just the moment the business went from little mags being chased by postal inspectors into… Well, just go to PornTube or XHamster and type in “Trannie Hypno Porn”, sit back, relax and don’t worry; the kids don’t usually start watching until the seventh grade.

The sixty year rail boom from 1833-1893 exactly mirrors the 1975-? electronic delivery boom. Early in both cycles huge fortunes were made… unicorns we might say. But neither boom produced late unicorns. So the reason why the present crop of unicorns is so unprofitable can be chalked up to the “late in the cycle” problem. And the next cycle? I’m betting on non-polluting energy (solar and wind) feeding very efficient, high-voltage electric networks with improved batteries everywhere. As usual, the pattern seems to require 1) an obvious need; 2) a new type of transmission network; 3) incremental improvements in 20-30 year-old technology; 4) Capital (which America is now lacking).

I think I just spotted a gleaming white horn emerging from Elon Musk’s forehead.