Yves here. This article provides an interesting counterargument to the widespread belief that Covid-related stimulus will generate inflation. Aside from the fact that the economy was below capacity before the Covid crisis (supported by the high level of involuntary part-time employment) and therefore its ability to support more demand is likely high than deficit hawks would have you believe, the lack of labor bargaining power will seriously dampen any one-shot spending from producing sustained wage gains. And remember, in an services-dominant economy, labor costs are the single biggest cost category.

And I am very fond of this sort of analysis. Ken Rogoff’s and Carmen Reinhardt’s study of 800 years of financial crises produced the important finding that high levels of international capital flows are strongly correlated with financial blowups.

By Kevin Daly, Managing Director and Senior Economist within Goldman Sachs’ Global Macro Research department and Rositsa D. Chankova, Analyst, Global Macro Research, Goldman Sachs. Originally published at VoxEU

The economic consequences of Covid-19 are often compared to a war, prompting fears of rising inflation and high bond yields. However, historically, pandemics and wars have had diverging effects. This column uses data extending to the 1300s to compare inflation and government bond yield behaviour in the aftermath of the world’s 12 largest wars and pandemics. It shows that both inflation and bond yields typically rise in wartime but remain relatively stable during pandemics. Although every such event is unique, history suggests high inflation and bond yields are not a natural consequence of pandemics.

In economic terms, the battle against the Covid-19 pandemic is often compared to a war – national resources have been commandeered in the battle against an ‘invisible enemy’, driving government debt levels sharply higher around the world (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020). For financial markets, one worrying aspect of this analogy is that the aftermaths of major wars have often been associated with rising inflation, high bond yields, and financial disruption.

But how close does the ‘pandemic as war’ analogy hold in practice? In a recent paper, we used data extending back to the Black Death in the 1300s to compare how inflation and government bond yields have behaved in the aftermath of history’s 12 largest wars and pandemics (Daly and Chankova 2021).

From Covid-19 to the Black Death: Very Long-Run Data on Inflation and Bond Yields

Our inflation and bond yield data come from two separate sources, both from economists at the Bank of England (Bank of England 2021, Schmelzing 2020), and our country sample consists of France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, the UK, Spain, the US, and Japan.1

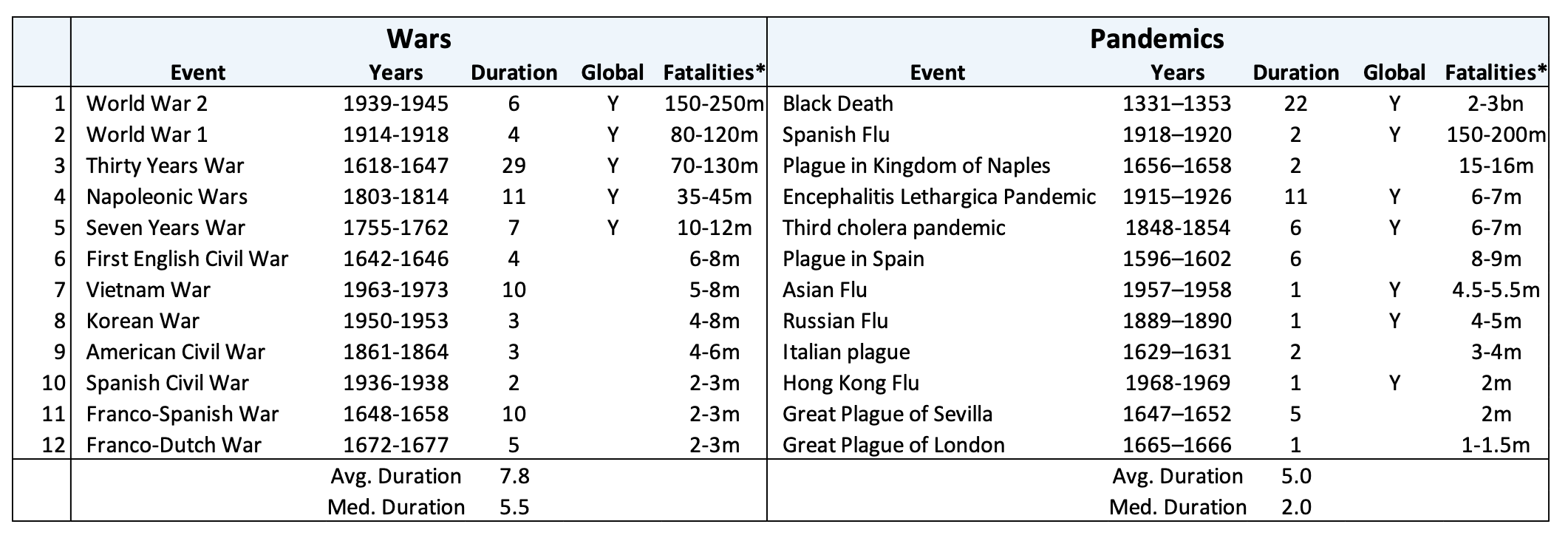

Our sample of wars and pandemics includes the 12 largest wars and pandemics measured by deaths, excluding regional wars and pandemics affecting countries/regions where we have no data (Table 1).2 Re-scaling fatalities to today’s global population, the cut-off point for inclusion in the sample is around two million deaths for wars and around 1-1.5 million deaths for pandemics (compared with an estimated 2.7 million deaths globally to date from Covid-19).3

Table 1 Our sample of major wars and pandemics

Notes: The 12 largest wars and pandemics measured by deaths, excluding regional wars and pandemics without economic data. *The fatalities data for wars and pandemics have both been re-scaled to today’s global population.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, Cirillo and Taleb (2020).

Wars Result in Higher Inflation and Bond Yields, Pandemics Do Not

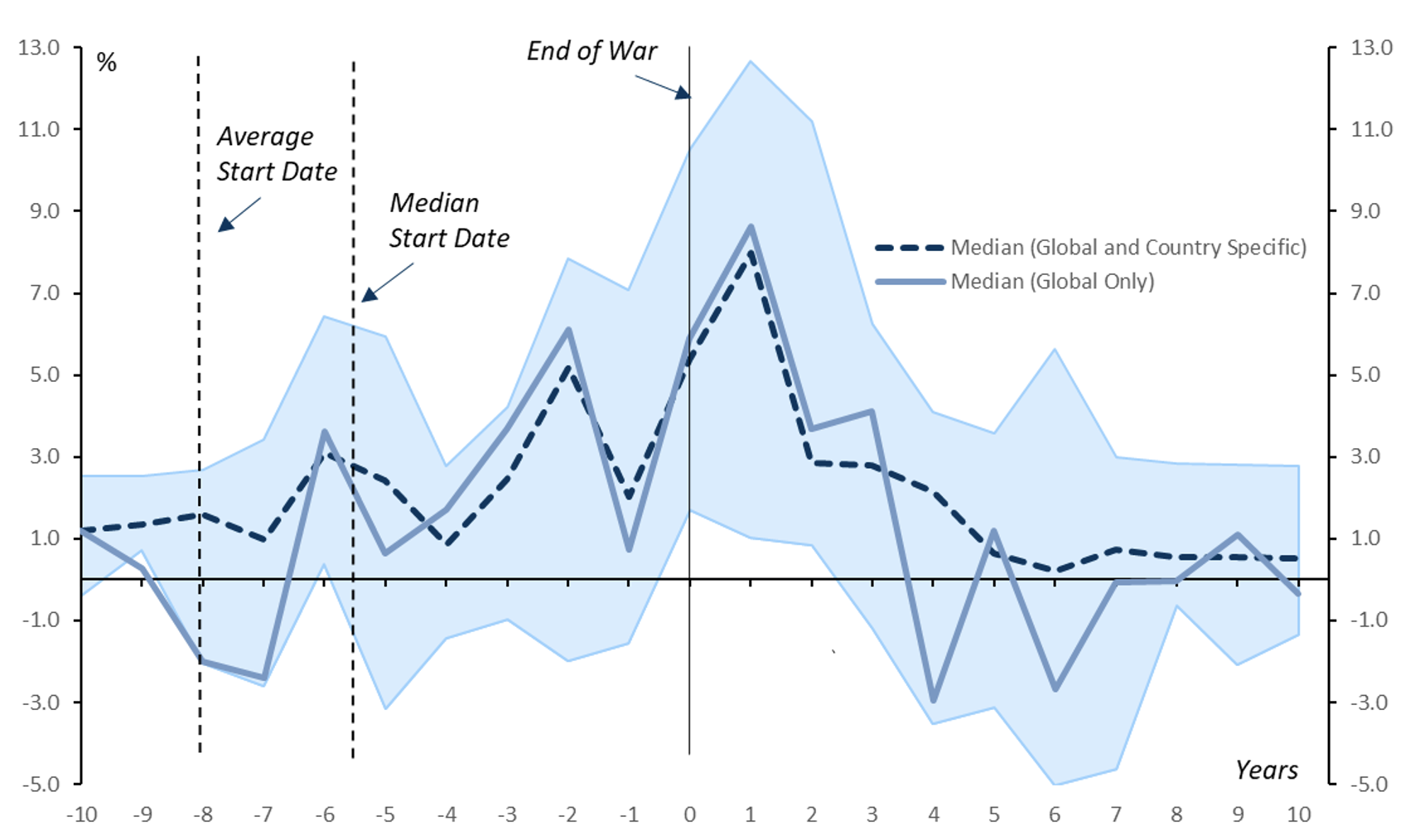

Figure 1 displays the median behaviour of inflation around major wars, together with its interquartile range (and also a median based only on global wars in our sample). Inflation has typically risen sharply both during and – especially – in the aftermath of major wars, with median inflation peaking at 8% one year after the war has ended.

Figure 1 Inflation has typically risen sharply both during and especially in the aftermath of major wars

Notes: CPI Inflation (% year-on-year) around wars, median and interquartile range.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, Bank of England (2021), Schmelzing (2020).

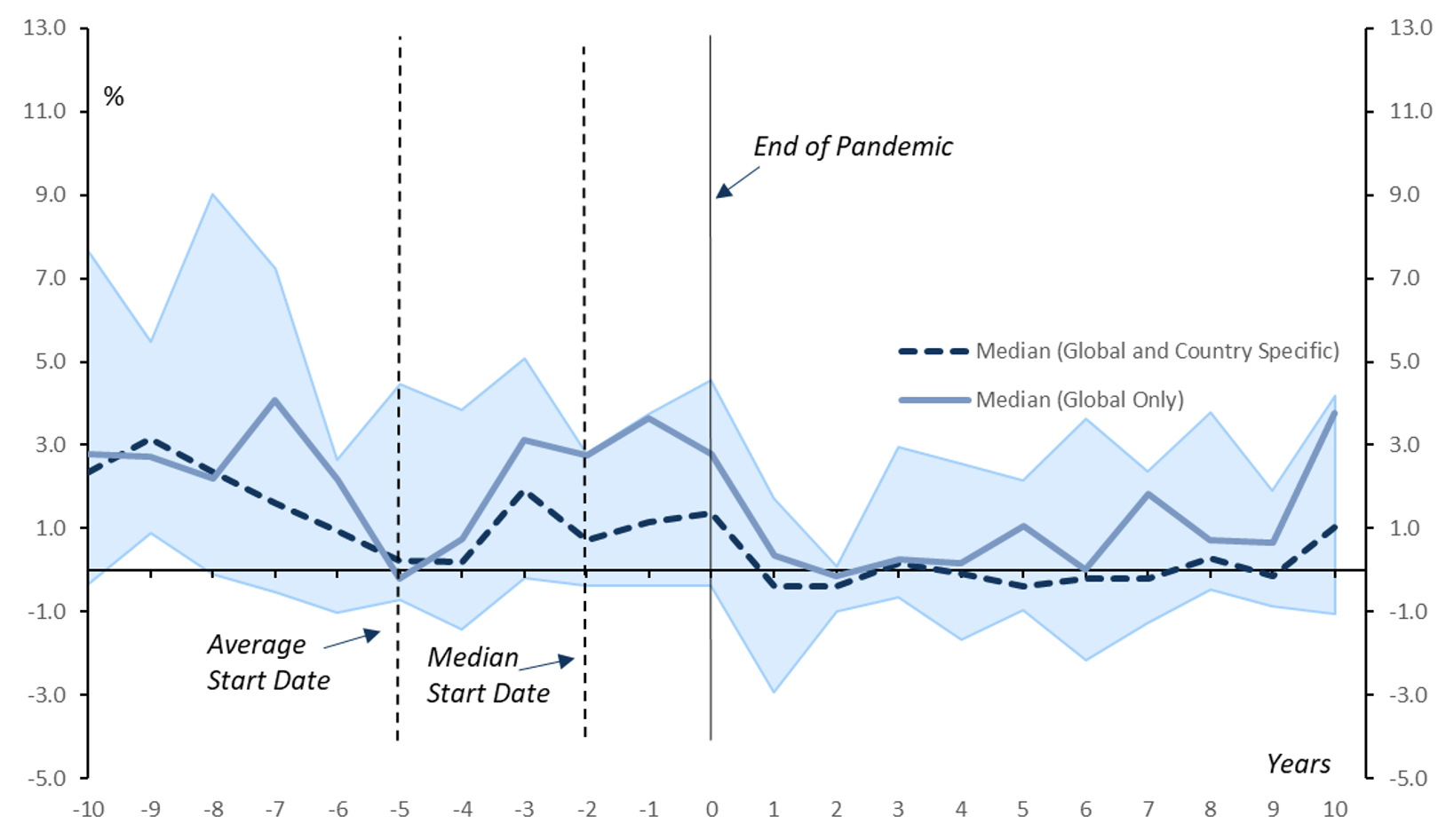

Figure 2 displays the same inflation data around the ends of pandemics. Inflation has typically remained weak during pandemics and declined in their aftermath, with median inflation falling below zero one year after the pandemic has ended and fluctuating close to zero for nine years after the pandemic has ended.

Figure 2 Inflation has typically remained weak in the aftermath of major pandemics

Notes: CPI Inflation (% year-on-year) around pandemics, median and interquartile range.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, Bank of England (2021), Schmelzing (2020).

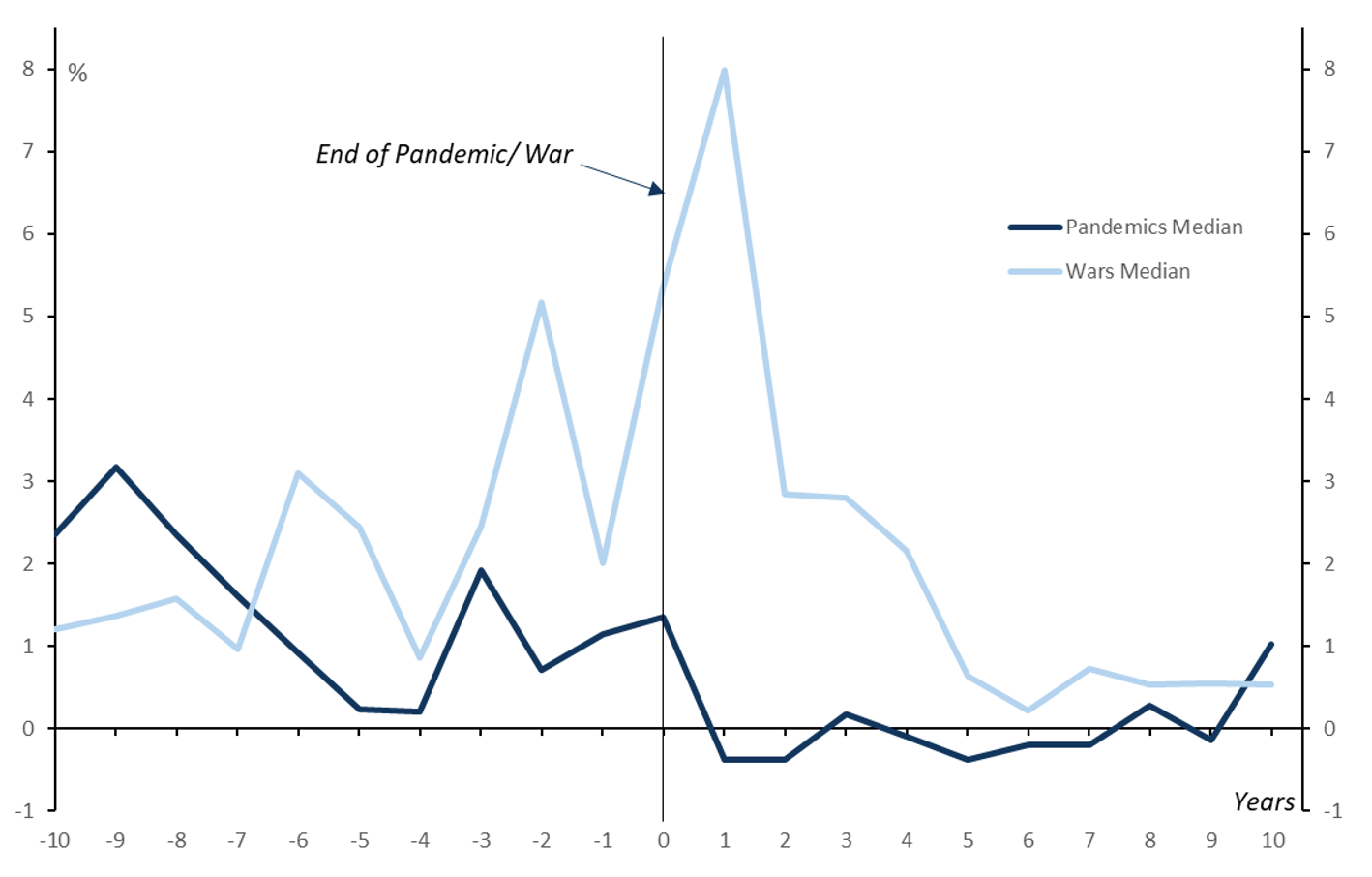

The contrast between the behaviour of inflation following wars and following pandemics is particularly clear in Figure 3, which plots median inflation rates across the 12 wars and pandemics.

Figure 3 Inflation has typically risen sharply following major wars, but not following pandemics

Notes: Median CPI Inflation (% year-on-year) around pandemics/wars.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, Bank of England (2021), Schmelzing (2020).

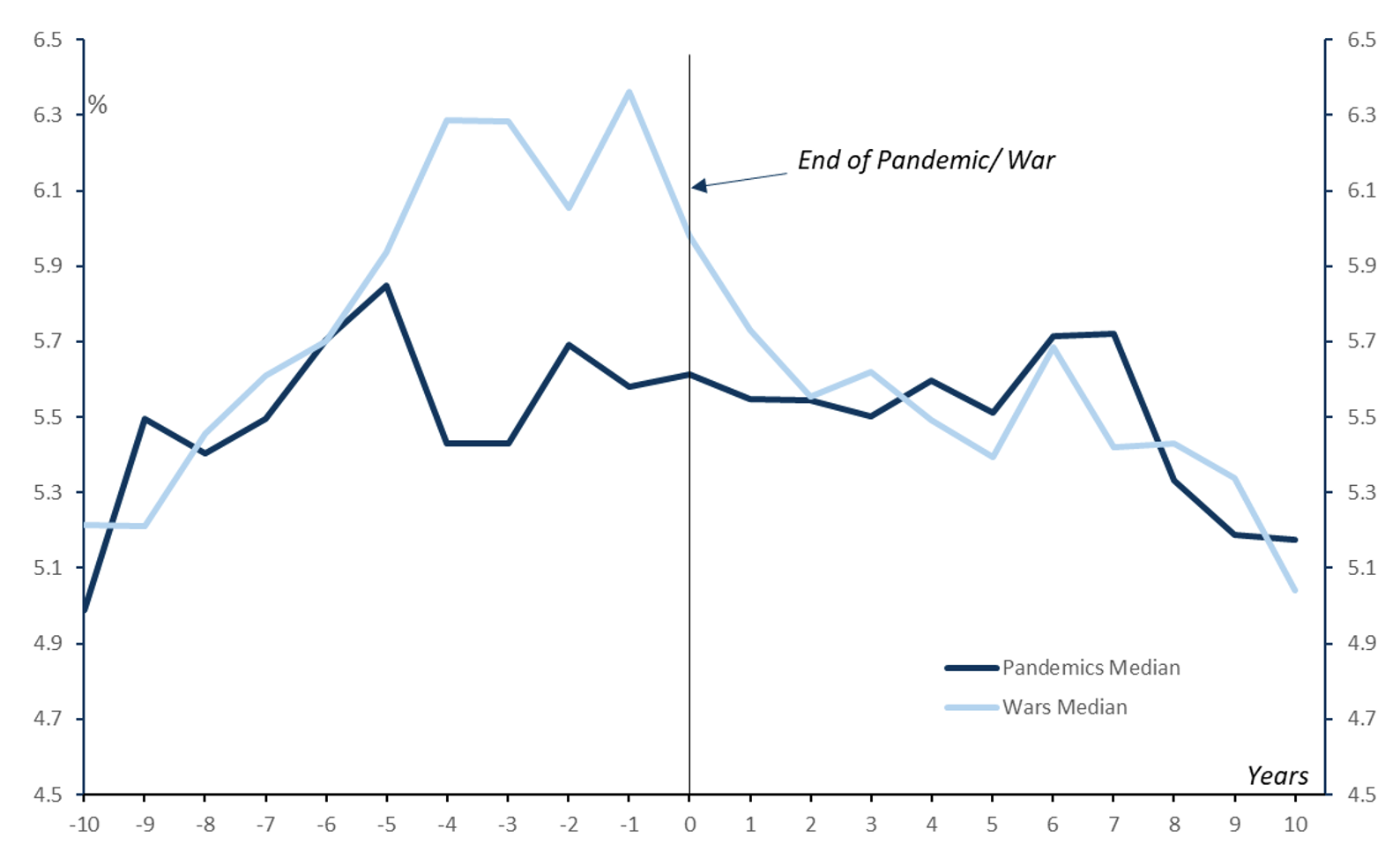

In Figure 4, we set out the same comparison for nominal government bond yields.4 Bond yields have typically risen during wars, with median bond yields increasing by around one percentage point to a peak of 6.4% in the final year of the war. By contrast, during pandemics, median bond yields remained stable at around 5.5%, before declining in the years following the pandemic.

Figure 4 Bond yields rise much more during wars than pandemics

Notes: Nominal ten-year bond yields (or closest equivalent) around wars/pandemics, median (%).

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, Bank of England (2021), Schmelzing (2020).

Lessons from the Past: From the World Wars to the Black Death

Averaging across a number of wars and pandemics can obscure important details. It is therefore instructive to also explore some key episodes in a little more detail, to see how the contrasts between wars and pandemics have played out:

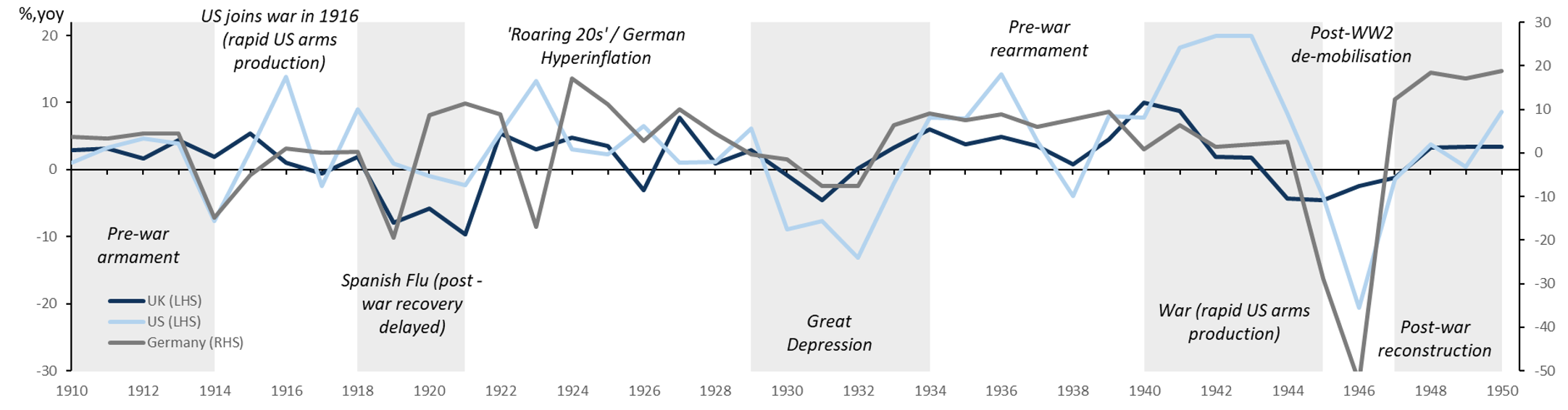

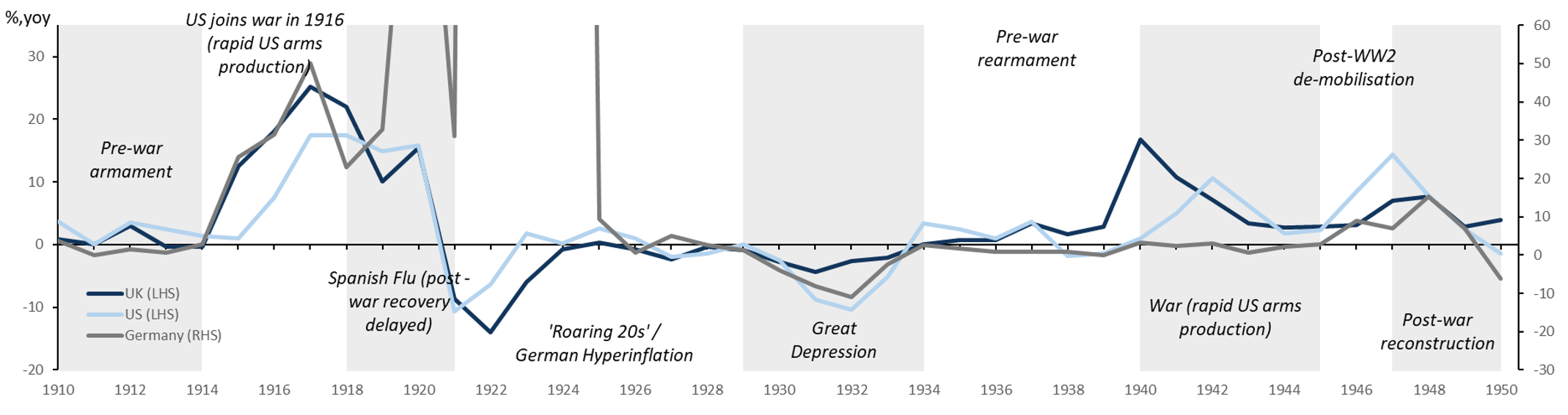

- WWI (1914-18): The years leading up to the outbreak of war were characterised by relatively rapid growth, partly fuelled by a rapid military expansion by European powers (Figure 5). Inflation accelerated sharply across Europe from 1914 onwards, as the UK, Germany, and France were forced to abandon the gold standard, rising to a peak of 50% year-on-year in Germany and 25% year-on-year in the UK in 1917. The US did not join the war until 1916 and growth and inflation both accelerated sharply in that year, with GDP rising 14% year-on-year and inflation reaching 17% year-on-year in 1917.

- The ‘Spanish Flu’ (1918-1920) is estimated to have killed around 40-50 million people worldwide, or 2-2.5% of the world’s population, around twice the number that died during WWI. While growth and inflation both weakened during the pandemic (Figure 5), it is difficult to determine from time series data alone whether this was due to the war ending or the pandemic. To distinguish between these effects, Barro et al. (2020) use cross-sectional data on war and flu deaths. On this basis, they estimate that the Spanish Flu reduced real GDP per capita by 6% on average and that, in contrast to the highly inflationary effects of WWI, the pandemic had a ‘negligible’ impact on the price level.

- WWII: In common with WWI, the years leading up to WWII were also characterised by relatively strong growth which, in Europe, was partly fuelled by rapid military expansion. Inflation accelerated sharply in the UK in 1939-40, as war was initially declared, and later in the US, as it subsequently joined the war (Figure 5). During the war years, GDP growth was exceptionally strong in the US (boosted by a significant increase in arms production and without the cost of war damage) but weaker in Europe (where governments strained to maintain arms production amid widespread war damage). Inflation remained high throughout the war years and through the initial post-war period, before declining in 1949-1950.

Figure 5 GDP and inflation over the two world wars and the Spanish Flu

a) GDP growth

b) Inflation

Notes: Evolution of GDP growth and inflation between 1910 and 1950 in the UK, US, and Germany. Sources: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, Bank of England (2021), Schmelzing (2020), Maddison.

- Napoleonic Wars: As tensions rose between England and France ahead of the Napoleonic Wars, the UK government tripled government spending over a five-year period (1792-97), partly funding this increase through a depletion of the Bank of England’s gold reserves (Broadbent 2020). Fears over the impending war resulted in a private sector switch from Bank paper into gold, causing the government to suspend gold convertibility. The price level subsequently rose by 59% over the following three years, although it stabilised thereafter and gold convertibility was subsequently restored in 1821.

- The Black Death: The bubonic plague reached England in late 1348 and, over the subsequent three years, resulted in a 30-45% reduction in the country’s population. As Jordà et al. (2020) discuss, the sharp reduction in labour was the primary cause of the Peasants’ Rebellion, a doubling of real wages, and a significant reduction in rates of return on land.

Why Wars Are Different from Pandemics: Wars Result in Overheating and the Destruction of Physical Capital

The contrast between the performance of inflation and bond yields during wars and pandemics makes intuitive sense, in our view, for two reasons:

- Wars drive aggregate demand up, while pandemics drive aggregate demand down: In wars, there is a long history of using debt-financed spending to fund increased war-related expenditure (before and during wars) and reconstruction efforts (in the aftermath), driving aggregate demand higher relative to war-damaged supply. In pandemics, by contrast, any increase in government spending is used to fill the gap left by absent private sector demand, with very different implications for the overall balance between aggregate demand and supply.5

- Wars destroy physical capital, driving investment and interest rates higher: Wars are often associated with the widespread destruction of physical capital, a development that increases the demand for investment and pushes interest rates higher. By contrast, pandemics do not result in any loss of physical capital and, if there is widespread loss of life, can result in an increase in the capital-labour ratio. Standard economic theory suggests that a higher capital-labour ratio should lower equilibrium interest rates, while raising real wages.6

Higher Inflation Is Not a Natural Consequence of Pandemics

Every war and pandemic is different, and we should be cautious of drawing lessons from events that occurred in the long-distant past and in very different circumstances. One feature of the current pandemic that is clearly distinctive to past episodes is the size of the government response. Equally, however, one can argue that an unusually large government response was necessitated by an unusually large collapse in private sector demand.7

What is clear is that history provides no evidence that higher inflation or higher bond yields are a natural consequence of major pandemics.

None of this precludes the possibility that higher inflation might result as a policy choice in the face of elevated debt levels. Higher inflation can bring welcome relief to debtors, including the government, by eroding the real value of their obligations. Faced with the choice of reducing debt through austerity or inflation, it is possible that policymakers might ‘choose’ higher inflation to help limit the need for tax rises and/or government expenditure reductions.

However, such a policy would require the cooperation of central banks to keep interest rates low, even as inflation is rising. And, in a world of independent central banks, even this route towards higher global inflation appears less likely than it did during past crises.

See original post for references

Looks interesting; I’ll have to read it later when I have more time. But, a minor pedantic quibble: The American Civil War ended in 1865–not 1864–as the authors indicate in the table.

Similarly, Napoleonic wars ended in 1815, not 1814, the Spanish Civil War in April 1939, not in 1938, and the Vietnam war in 1975, not 1973. The authors state in an endnote:

They give no explanation about how they gauge the significance of fatality figures — for my taste, a whiff of data fudging. To be frank, I find that those VoxEU articles often rely heavily upon quantitative modelling that ultimately seems to me too contrived to be truly persuasive.

Good catch, vao. I didn’t see that caveat in my earlier haste.

Just wondering how to apply this info to our present situation of environmental destruction, overpopulation, rising hunger, new-age pandemics, modern but inefficient transportation, weather catastrophes, depleted oceans, aging non-productive populations and high tech (possibly very economical) warfare. And the use of fiat as opposed to gold coins literally carried around in treasure chests. One thought is that a modern war wouldn’t necessarily “destroy capital” like previous wars but it would definitely push the planet over the edge and into mass extinction. I think it would be a good idea to start calculating “capital” as a per-capita phenomenon because it is now based totally on human consumption. So many ideas; so little time ;-). And war could be good if it were a war against environmental destruction, no matter how much it cost to prosecute it. We do have an infinite supply of digits. But we still have such stingy hearts.

“However, such a policy would require the cooperation of central banks to keep interest rates low, even as inflation is rising. And, in a world of independent central banks, even this route towards higher global inflation appears less likely than it did during past crises.”

You lost me at the world of independent central banks. The CB are never independent. We should rather worry if our Congress will have the will to act if inflation is too high. Historically, democracy’s record of performance in inflations was never good.

Numerous were the democracies which could not arrest inflations without undergoing either collapse of the currency or political convulsion or both.

Few were the democracies which did not fail in this way once big inflations were established.

Inflation is the plague of weak governments, and democratic government is in essence weak government. The American democracy has become fully as weak as the supremely democratic Weimar republic that failed in the German inflation.

Democracy’s weakness is inability to act. No one, not the most ardent democrat, would maintain that ability to act is one of democracy’s strong points. That is the very antithesis of democracy.

Given the action to be taken, it is the autocracy which can take the action quickly, efficiently, and forcefully, and the democracy which cannot.

This is not to advocate autocracy, which has many well-known failings of its own. It is merely to say that democracy is not in one of its fields of strength, but of weakness, when it needs to take immediate, drastic, intelligent, and single minded action in a matter as perplexing, as fraught with factional conflict, and as vexed with difference of opinion as inflation. Rising against military attack comes easily to democracy; rising against inflation does not.

They’ll do the same they do now and change the way they count inflation. I’ll add that i suspect the only inflation that frightens the rulers is wage inflation.

it is the autocracy which can take the action quickly

Yes absolutely. We must mind the bosses and their orders for acceptable outcomes, none of which include reducing their autocratic control.

What democracy are you talking about?

when it needs to take immediate, drastic, intelligent, and single minded action in a matter as perplexing, as fraught with factional conflict, and as vexed with difference of opinion as inflation

Solving vexing differences of opinion is democracy’s main strength. What you’re worried about is the autocratic minority currently in charge won’t be calling all the shots. I haven’t seen “intelligent” action in quite some time. Self interested grifting is the name of the game.

The CB are never independent.

Err, Independent of what precisely. Reality? Truth?

This chimes with my intuition about pandemics & inflation, although I never had time (or will, or someone paying me:) ) to do the research on it.

Makes sense to me. We have seen the feds spend incredible amounts of money to help demand catch-up, but Biden’s bill to increase infrastructure spending (war on infrastructure) seems to be stalled or DOA.

Central banks are not independent in monetary sovereign nations. Or even in arrangements like the EU, where 19 nations gave up their independence and their domestic currencies. The ECB is buying debt like there’s no tomorrow. To keep the members afloat. Not going to work because there is no tight confederation there. The Feds are holding a lot of the debt in their own accounts, not selling it all to the secondary markets. Japan’s federal govt. owns 92% of its debt. Would be more transparent just to create the required currency, and not issue any debt. But that wouldn’t work for the One Percent, the oligarchs. They love their socialism.

This is a good article – very readable, supported by evidence, and with both the conclusions and their limitations clearly stated. Thanks for featuring it.

Intuitively I tend to think of inflation and deflation as changes in the ratio of currency in circulation to overall productive capacity. In that view it makes sense that destruction of productive capacity would be inflationary (Weimar Germany being an extreme example) and reduction in the velocity of money due to a fall in demand from changing consumer behavior would be deflationary.

I don’t think inflation is inherently bad (historically when it has been bad it’s usually been a symptom of bigger underlying problems). It does create winners and losers and needs to be evaluated in that context. The biggest losers from inflation are creditors, who currently have an outsized influence on government policy in the US (which flows through to the rest of the world) and that’s arguably why austerity has featured so prominently in recent administrations. Whether that approach serves the interests of society as a whole is a question worth asking.

Interesting, but….

Wars typically involve large increases in state borrowing. Except for the current pandemic, I doubt whether states borrowed much to replace lost revenues, provide relief or replace incomes lost in previous pandemics.

There has been nothing like the current increase in the money supply. It remains to be seen how the recent increase will find its way from the Fed’s balance sheet into the real economy.

It generally doesn’t, as demonstrated in the Great Financial Crisis.

No Inflation? Visit your local Home Depot.

Stud $6.00

Plywood $44.00

Electric wire, $25.00 for a reel

But inflation is low,

and Pigs can fly.

I am currently trying to buy a new bicycle. If I order it now, it won’t arrive before 2022. Various bike parts are currently unavailable, meaning that local shops can not do all repairs like before. You can still get some online, but for swelling prices.

Local hardware store now has various empty shelves and is not accepting orders due to price uncertainty. They had not had such issues last spring.

Inflation is a reality. Right now it is primarilly a product of the manufacturing outages in the past year. Factories will soon resume to meet the reality of inflated commodities prices.

“What is clear is that history provides no evidence that higher inflation or higher bond yields are a natural consequence of major pandemics.”

What is clear to me from reading this post might be that there have been a lot more wars than major pandemics. Of the two major pandemics mentioned the impacts of the Spanish flu might be a little difficult to separate from the impacts of World War I and the impacts of both might be a little difficult to separate from the way the post World War I debt was handled. The data on the Black Death with an estimated 30-45% decrease in population might not be a good example for predicting the impacts of the Corona pandemic [I hope the Black Death and the Corona pandemic will prove incomparable!]. Using bond yields as a proxy for ‘inflation’ seems about as useful and meaningful as using the stock market average as a proxy for the economy. I believe the US economy is structured sufficiently differently than economies of the past that I am not sure how well past performance predicts future performance.

I am concerned about how many bumps in costs for things I might need will ratchet at higher levels. The way ‘inflation’ is measured I also wonder whether any of the increases in the costs for things I need will be reflected in the official calculations of ‘inflation’.

Where is the inflation?

If you copy Japan’s solution to a financial crisis you are going to kill growth and inflation.

How did Japan avoid a Great Depression?

They saved the banks

How did Japan kill growth and inflation for the next thirty years?

They left the debt in place and the repayments on that debt killed growth and inflation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

Western experts had put Japan’s problems down to demographics, so they didn’t realise the drawbacks in copying Japan.

Not considering private debt is the Achilles’ heel of neoclassical economics.

They couldn’t see the real problem.

It’s not as bad as Japan as we didn’t let asset prices crash in the West, but it is this problem has made our economies so sluggish since 2008.

Western governments are always fighting the drag anchor of all that private debt in the economy, which tends to kill growth and inflation.

Japan has been like this since 1991.

The experts expect inflation as they can’t understand the deflationary forces that are at work.

Where is the inflation (part 2)?

Keynesian economics – consumer prices

Neoclassical economics – asset prices

At the end of the 1920s, the US was a ponzi scheme of inflated asset prices.

The use of neoclassical economics and the belief in free markets, made them think that inflated asset prices represented real wealth accumulation.

1929 – Wakey, wakey time

Ah yes, I remember now.

You need to look in the right place for the economics you are using, like the Chinese who saw their financial crisis coming.

Davos 2018 – The Chinese know financial crises come from the private debt-to-GDP ratio and inflated asset prices

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1WOs6S0VrlA

The black swan flies in under our policymakers’ radar.

They are looking at public debt and consumer price inflation, while the problems are developing in private debt and asset price inflation.

The PBoC knew how to spot a Minsky Moment coming, unlike the FED, BoE, ECB and BoJ.

It doesn’t matter what the reasons are. We have had steady inflation for decades. I no longer pay any attention to government statistics. I only pay attention to what things cost, and the cost is always going up or the packaging is shrinking. I keep an older (by older I mean two months ago) 6-pack of paper towels as a measuring guide to what I currently get, and there is a significant difference in size. Pet food cans are smaller, Tuna cans are smaller. In fact nearly all food packaging is smaller. Not to mention how many empty spaces there are in stores. It’s the boiling frog syndrome and the plebes just put up with it.

I wanted to reply yesterday, but didn’t get a chance to. I wanted to get some opinions from people way smarter about this than me.

I’m definitely not a hard-money type and even now, I’m tuning out Larry Summers and all the usual monetarist panic about hyperinflation.

However, there are a few, fuzzy intuitions that bother me and make me wonder: what if this time kind of is different, for very material reasons specific to America today? Could we be spiraling into a relatively nasty, sustained stagflation?

Pretty much, I’m relatively young, but old enough to remember even the dot-com burst. And over time, I’ve come to the belief that when a particular economic issue gets habitually downplayed & compartmentalized, across the political spectrum, that’s a big red flag that you’re looking at the lit powder-keg.

Is it just me, or does it seem like regardless of where you look, left-leaning economists, right-leaning, the talking-heads on CNBC, nobody seems to factor in a few things:

1. How much we rely on imports (which are increasingly clogged or diverted)

2. How purchasing these imports requires a strong-dollar at low-interest rates (which looks increasingly irreconcilable)

3. Repeated examples, going back to before the pandemic, whether in goods, services, or management, that American competence isn’t nearly as much of a thing anymore

4. An overwhelmingly demoralized labor-force, to the point of nihilism in cases

Granted, I definitely have a bearish personality, and personal experience in education & engineering has made me even more pessimistic about points 3 & 4. Doesn’t the whole narrative about a successful reopening (without stagflation) rest on US “capacity” coming back on all cylinders? And wouldn’t even any 1 of these 4 points being reasonably true, completely sabotage that?

I don’t think historical analysis is adequate. Global central banks have pumped trillions into the global money supply, almost 8 trillion in the US alone. Other than the plunder of the Americas, nothing much like this has happened before. Assuming all those assets are money good, as the Fed routinely does, both the sale and runout of those assets would take money out of the economy, or at least the finance, stock and RE markets. This suggests that the Fed would be forced to maintain its low rates and special vehicles in its overnight markets for some time. While I am not competent to prognosticate, the very large pile of assets on central bank books suggest that while this historical analysis is interesting, it may not be all that germane.