More and more public pension trustees are willing to say that the private equity emperors are looking awfully naked. LACERS has joined the club, with board member Sung Won Sohn sharply criticizing results considerably below LACERS’ benchmarks. Sohn’s views carry some weight, since he’s a prominent economist and former banker.

But as important, more and more studies and papers are confirming what we’ve said for years: that private equity does not deliver superior returns. We’ll briefly discuss the unwelcome truth-telling at LACERS and then turn to an important study by the authoritative CEM Benchmarking which found that private equity hadn’t outperformed since 1996. This is a devastating finding, since other analyses that questioned private equity results tended to date the shift to unimpressive results at around 2006.

CEM has good grounds for claiming that it has the best database in the industry, and CEM also has to be careful not to alienate its pension fund clients. So for CEM to come to this sort of conclusion is a sea change.

But for the moment, back to LACERS. LACERS is the Lost Angeles City Employees Retirement System. It’s a small fish compared to CalPERS, at $21.4 billion in assets versus CalPERS’ over $400 billion. However, there’s no reason that LACERS smaller size should be an obstacle to doing well if good returns were generally available in private equity fund investments. CalPERS is so large that absent bringing private equity in house and cutting out hefty private equity fund fees and costs, it’s going to get index-like returns. And the industry has been dominated by larger, leveraged buyout-type deals which have delivered lower returns that industry averages. So if anything LACERS smaller size in theory could allow it to do a bit better than the norm. But as we’ll discuss later, the evidence continues to mount that private equity, properly measured, not only doesn’t deliver superior returns but hasn’t, according to the authoritative CEM Benchmarking, since 1996.

LACERS, like so many other desperate investors, was considering puttin even more chips on the private equity roulette wheel by increasing its asset allocation from 14% to 16%. Sohn’s recap of the sorry results led to a decision being postponed. From Justin Mitchell in Buyouts Magazine:

“I know in the long term private equity is supposed to give us very healthy returns, but that of course has not been the case for quite some time,” said Sung Won Sohn at Tuesday’s board meeting. “It’s been anything but healthy returns…

“I view that as an underperforming asset that will continue to underperform,” he said.

Sohn pointed to the most recent performance report, presented to the board that day. It showed the pension’s $2.45 billion PE portfolio returning 13.71 percent over one year, 12.64 percent over three years, 11.81 percent over five years and 12.44 percent over 10 years, net of fees. The numbers were as of December 31, 2020 but lagged a quarter.

These returns all trailed the benchmark, which came in at 24.47 percent over one year, 17.89 percent over three years, 18.86 percent over five years and 17.42 percent over 10 years.

Look at those figures. The least bad measurement period was ten years, where LACERS’ private equity results were 2 basis points better than 5% below the benchmark. The later sub-periods were worse. And this is using a perfectly sane benchmark, the Russell 3000 plus 300 basis points.

Not surprisingly, Private Equity International reported in February that LACERS is looking to change its grading scale to cover up its poor performance. It’s using Covid as the excuse, to the Cambridge Associates All US Private Equity benchmark. Oxford professor Ludovic Phalippou for some time has discussed the vogue for changing to more flattering benchmarks to help staff get performance bonuses.

And the issue of benchmarks was an important focus of the CEM Benchmarking study, which was published in the Journal of Investments last year. We posted on it then based on a write-up in the Financial Times; only recently did we learn we could obtain access to the full paper, as you can here. CEM set forth four criteria for benchmark choice. One was that it be hard to beat, which as we’ve pointed out with CalPERS’ benchmark change and Professor Phalippou has described more generally, is precisely what public pension funds appear determined to undermine.

Another key criterion is that a benchmark be investible. The Cambridge Associates benchmark is fail here, and even worse, not even verifiable since its components are, natch, private. The other criteria are highly correlated and have similar volatility.

I also doubt that the proposed change at LACERS, even if approved, would shut up Sohn. He looks quite capable of keeping tabs on the Russell 3000 and continuing to compare private equity results to it, and demanding explanations from the consultant as to why their metric is lower than public stocks plus a risk premium, should that prove to be the case.

CEM contends, credibly, that their database is the best because it is from an extremely large number of clients in the US and Canada, contains all their dogs (it described one with a negative 100% return net of costs!) and reflects CEM going back to their clients when needed to clean up data (among other things, they see inconsistent reports for the same fund at different accounts and sort out which one was right and get the erroneous one corrected). Their other big correction to widely-used performance reports is they reject IRR and employ portfolio level time-weighted returns.

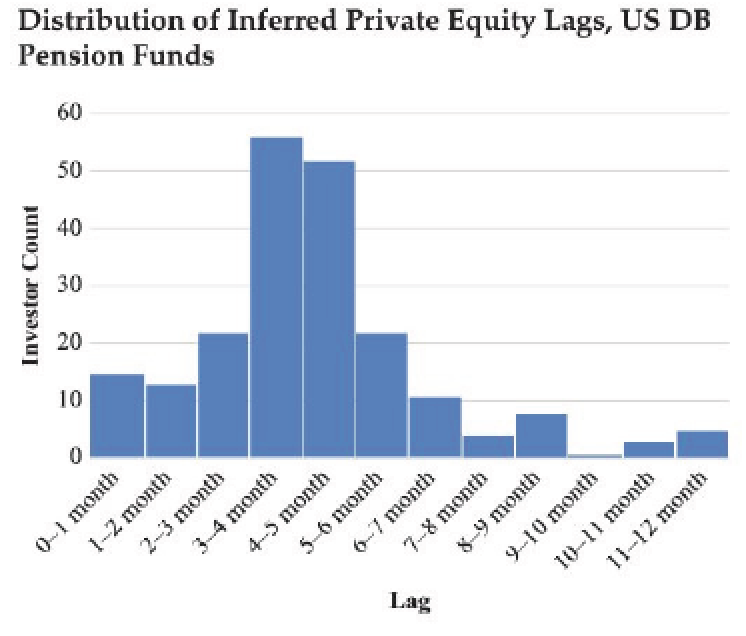

CEM also addressed a long-standing deficiency with private equity reporting: that investors almost without exception engage in the apples and oranges practice of reporting results on a delayed basis, usually a quarter. So, for instance, at CalPERS, June 30 fiscal year end returns show private equity results as of March 31. CEM corrected for the lag and found, not surprisingly, that the fiction that private equity isn’t highly correlated with stocks goes poof. Differences in investor practices on how they lagged their reports also produced the fiction that private equity returns are less volatile than they really are.

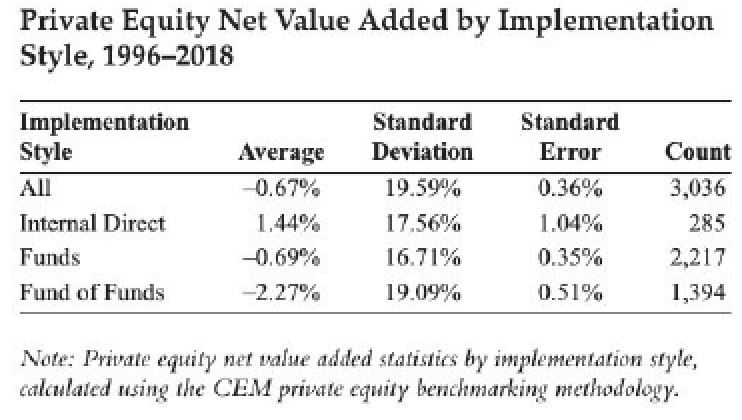

CEM, using a simple mix of small-cap indexes, found that even though private equity funds deliver what looks to be outsized raw returns, they fall short of CEM’s benchmark since 1996. However, as we’ve also said for some time, the big exception is investing in house, which CEM calls “internal direct”. And the worst, natch, is fund of funds, which have an extra layer of fees.

There are two additional reasons the CEM findings are deadly. First, the time period they look at, going back to 1996, includes a substantial portion of the 1994-1999 “glory years” where private equity firms were coming back from a period of disfavor after the late 1980s leveraged buyout crash. Less competition for deals meant better buying prices and better returns. Alan Greenspan dropping interest rates for a full nine quarters after the dot-com collapse was the first episode of the Fed driving money into high risk investment strategies by creating negative real returns for a sustained period, and the rush of money into private equity elevated deal prices.

The industry story line has been that if you participated in those “vintage years,” you reaped outsized results. CEM has demonstrated you would have done even better in a simple stock index, a full 67 basis points, which over the long investing horizon of pension funds and life insurers, adds up.

Second, CEM used unlevered indexes for its benchmark. If CEM made that adjustment, even the in-house funds might look only so-so on average.

It took a wag in the Financial Times comments section when the pink paper reported on this article to summarize what was really going on:

There a strange but widely held assumption here that PE is operated to enrich people other than the general partners.

Indeed.

Excellent as always. Given the intersection of pension boards being political appointees and PE firms employing and lobbying politicians, perhaps we should not be surprised at all. It’s quite nice to have hard irrefutable facts on the side of an argument that seems obvious from arm’s length.

No mention of the benefits of private equity?

Out of fairness I’d expect a quote from Fred Buenrostro…

Isn’t he behind bars? (I don’t mean mixing drinks.)

Again cui bono?

If it’s obvious to me, someone who only invests in index funds that when fees are considered, PE is a loser.

Someone is getting paid off, either now, or through the implicit promise of a few years of 7 figure consulting gigs when they retire from a retirement system.