Yves here. While this paper pursues a very important question about norms, I have strong doubts about its conclusions, which is basically that there are clear tipping points and they are durable. For instance, abortion rights are far from settled in the US. The women’s liberation movement made the huge tactical error of not getting abortion rights enshrined in legislation, and instead relied on the Supreme Court to hold their win. Richard Nixon made sure that abortion rights meant less than they seemed to by refusing to fund the procedure. And despite the belief that women can get an abortion, that right is increasingly empty as MDs are not learning how to do abortions in med school, Six states have only one clinic, and in 2014, 90% of US counties had no clinic. Moreover, many conservative state make abortions a two-day process by requiring women to hear lectures about how they are killing a fetus and watching videos and then waiting 24 hours after that to have the abortion. How many low or even middling income women can afford to take two days off from work, even before allowing for possible long driving times?

And how about other areas where opposition to the status quo hasn’t led to “norm change,” like gun control and overpriced crappy health care?

By James Andreoni, Professor of Economics, University of California, San Diego; Nikos Nikiforakis, Professor of Economics, New York University in Abu Dhabi; and Simon Siegenthaler, Assistant Professor, School of Management, University of Texas at Dallas. Originally published at VoxEU

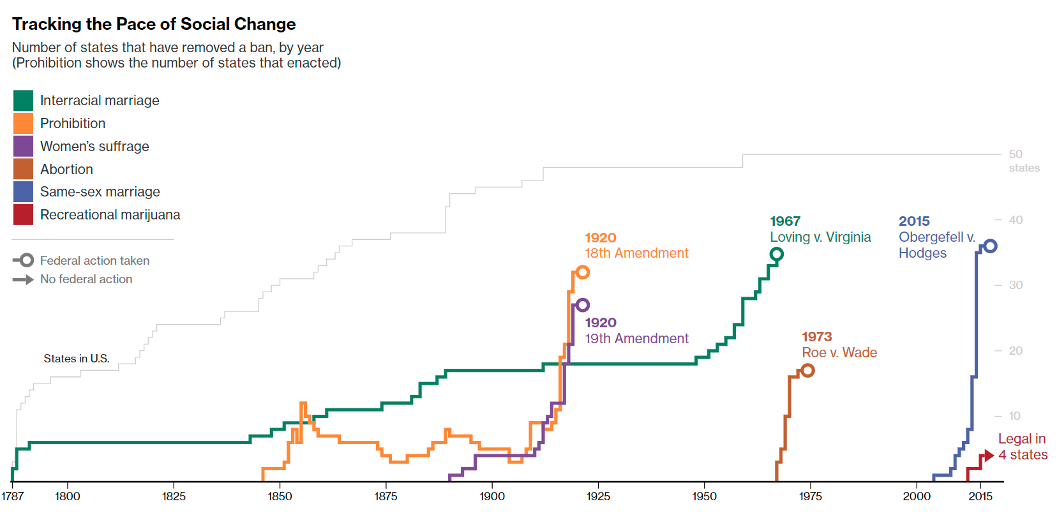

Some social norms – the informal rules governing which actions should be rewarded or sanctioned in a particular society – exist for so long that they seem permanent. And yet, historical data document significant instances of sudden social change, such as widespread support for gay rights. This column presents evidence from a large-scale lab experiment designed to predict the tipping point at which such change occurs. The model suggests that effective policy interventions can raise the likelihood of reaching the tipping threshold, thereby promoting a beneficial change in social norms.

Social norms – informal rules about what actions should be rewarded or sanctioned – are ubiquitous in human societies. Some social norms have been around for so long that it is difficult to imagine life without them. And yet, these norms are sometimes replaced in favour of new rules that better reflect the preferences of the members of a society. Two prominent examples involve the abandonment of norms against homosexuality, and norms supporting gender discrimination in the workplace. As can be seen in Figure 1, social change can sometimes be rapid and nearly impossible to anticipate.

Figure 1 This is how fast the US changes its mind

Source: Tribou and Collins (2015)

For norm change to occur, there needs to be a social wave of individuals that moves against the status quo; for instance, against the ban on same-sex marriage and for the normalisation of being gay. If the group that mobilizes is large and visible, the social cost for embracing a new behaviour decreases and eventually reverses. A social tipping point occurs (e.g. Schelling 1978, Bicchieri 2016, Centola et al. 2018). An illustration of such a process is the rapidly increasing number of people in 2013 who signalled their support for same-sex marriage using red equal signs, and later rainbow flags, on their social-media profiles.

Figure 2 As the US Supreme Court took up arguments in key marriage rights cases in 2013, the red equal sign released by the Human Rights Campaign replaced more than 15 million profile pictures on social media platforms in support of same-sex marriage

Historical data clearly documents instances of sudden social change (e.g. Kuran 1991, Jones 2009, Amato et al. 2018). These data, however, do not permit us to identify models that can predict social tipping. This is problematic, as it is difficult to know if social norms accurately reflect societal attitudes at any given point in time, or whether there is a hysteresis which could call for an intervention to stimulate change. Recently, researchers started using experiments in controlled laboratories to study the process of social change (e.g., Centola et al. 2017, Smerdon et al. 2019, Bicchieri et al. 2020). In a new study (Andreon, Nikiforakis and Siegenthaler 2021), we present evidence from a large-scale lab experiment designed to test and empirically validate a widely used theoretical class of model for social tipping: threshold models.

Threshold Models

Threshold models assume that an individual’s willingness to deviate from a social norm depends on the proportion of others in the society that previously deviated from it. A society reaches a ‘tipping threshold’ when the proportion of people deviating from the norm becomes large enough that even individuals who are risk averse, conformist, or have pessimistic expectations about the prospects of change have an incentive to follow suit (e.g. Granovetter 1978, Schelling 1978, Efferson et al. 2020).

Intuitively, the size of the tipping threshold measures the entrenchment of an established norm. The higher the threshold, the more difficult it becomes for a society to abandon a norm. This relation, however, had not been tested, nor is there evidence to identify at what threshold a social norm can persist even at the detriment of most of a society’s members.

Using numerical simulations, we show that in such a model there is a critical tipping threshold of 35% of the population, for plausible distributions of risk/conformity preferences and expectations. That is, when the benefits and costs of norm change are such that the tipping threshold falls below the critical threshold of 35%, then the probability of norm abandonment is predicted to be close to 100%, because enough individuals are willing to persist in leading change. In environments where incentives are such that the tipping threshold exceeds 35%, however, the probability of social tipping quickly drops to 0%, because the critical mass for triggering change is unlikely to accrue.

Experiment Design

In Andreoni et al. (2021), we use a threshold model to predict social tipping in 54 experimental societies, each consisting of 20 individuals, and test different policy interventions that could promote norm change. The individuals interact over multiple periods in a social-tipping game with the following incentives:

- failing to choose the same behaviour as most others results in a penalty – depending on the treatment, either exogenously fixed or endogenously chosen by the participants – which creates a need for coordination and conformity, and

- preferences over alternatives gradually change over time, which creates a need for change.

That is, in the first round everyone prefers alternative A (equilibrium A), but preferences change over time until after a certain point, when nearly all members of a society would prefer change to alternative B (equilibrium B). The process by which preferences change is public knowledge, thus ruling out incorrect beliefs about others’ preferences as a reason for detrimental norm persistence (e.g. Granovetter 1978, Smerdon et al. 2019). Despite this, reaching a tipping point can be difficult given the pressure to conform and the history of adherence to the old norm, which affects individual expectations.

Persistence of Detrimental Norms

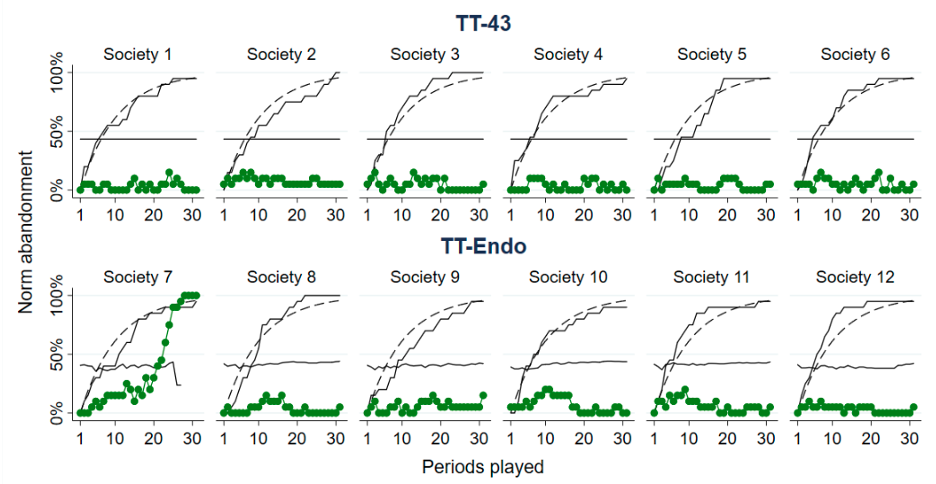

The data from the experiment demonstrates that societies can easily get caught in conformity traps. In particular, the baseline condition TT-43 implements a tipping threshold of 43% for which the model predicts no social tipping. The first panel in Figure 3 depicts behaviour for this condition in the six societies that participated in TT-43. The increasing solid line shows that the proportion of individuals who would prefer to abandon the old norm increased over time (the dashed curve shows the expected proportion). However, the green line with circled markers shows that the proportion of individuals who choose to abandon the norm never exceeded 20%. Hence, societies never reached the tipping threshold (given by the horizontal line at 43%), and norm abandonment did not occur.

Figure 3 Time series of norm abandonment in TT-43 with a tipping threshold of 43% (horizontal line) and for the condition where subjects chose endogenously the pressure to conform and thus the tipping threshold (TT-Endo)

Notes: Norm abandonment is shown as the line with circled markers. The dashed concave curve indicates the theoretically expected fraction of subjects preferring to abandon the norm; the solid increasing line the corresponding realised fraction.

The second panel in Figure 3 shows behaviour in condition TT-Endo, which is identical to TT-43except that subjects could set the tipping threshold themselves by choosing how much others are penalised when failing to conform to the norm. In this condition, we did not impose strong incentives for coordination. Choosing a low penalty would correspond to a high tolerance for norm digressions. Strikingly, subjects set the tipping threshold too high for tipping to occur and five out of six societies failed to achieve a norm change. The reason is threefold:

- those who prefer the status quo (e.g. a ban on same-sex marriage) initially choose high penalties for norm deviators

- to prevent the costs associated with attempts at transitioning to the new norm, individuals who would prefer change also start to choose high penalties; hence

- change fails to occur even when nearly everyone would prefer the new alternative. That is, creating a hostile environment between those seeking change and those favouring conformity can perpetuate the status quo.1

How to Escape the Conformity Trap

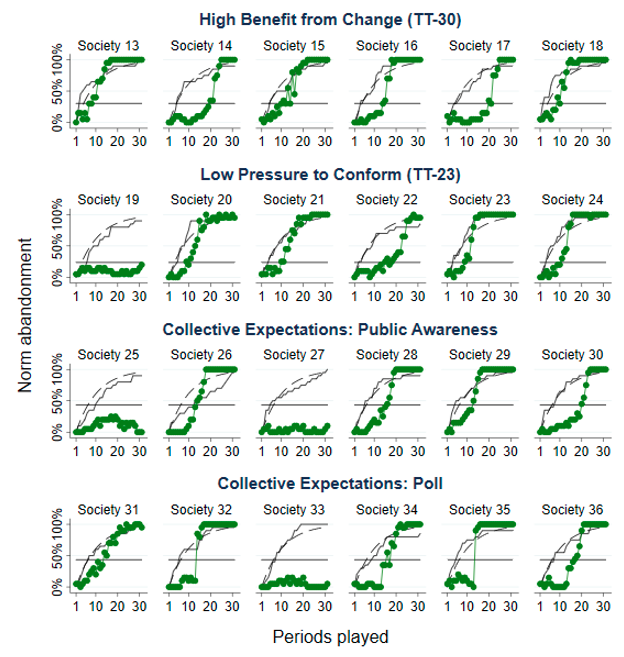

Can policy promote beneficial norm change? The model suggests that effective interventions lower the tipping threshold. We examine this possibility in two conditions. Condition TT-30 implements a tipping threshold of 30% by increasing the benefit of change. In the field, this could correspond to an information campaign about the economic gains, health benefits, or scientific advances associated with a norm change. Condition TT-23 implements a tipping threshold of 23% by exogenously lowering the penalty for norm transgressions. In the field, this could correspond to campaigns that promote tolerance towards alternative beliefs and behaviours, or that illuminate the moral certitude of a particular stance. The first two panels in Figure 4 show that these conditions were indeed successful. In eleven out of twelve societies, the fraction of individuals deviating from the established norm increased over time until the tipping threshold was reached, and rapid norm change followed.

We also explored the efficacy of interventions that could affect expectations about change. In condition ‘public awareness’, we highlighted that all members of a society would prefer change by providing precise information about the predominant preferences in any given period. In ‘poll’, individuals could express their preferred social alternative via a poll that took place when a clear majority preferred abandoning the old norm. The lower two panels in Figure 4 show that, despite a high tipping threshold of 43%, these interventions led to change in ten out of twelve societies. Social tipping can therefore critically depend on a common understanding of and perspective on the benefits from change. For example, choosing marriage equality as the angle for gay rights helped to create more sympathy for gay people, and generated enough momentum in a sufficiently broad demographic to bring about the normalisation of being gay.

Figure 4 Time series of norm abandonment for the conditions with high benefit from change with a tipping threshold of 30% (TT-30), low cost of miscoordination with a tipping threshold of 23% (TT-23), and two conditions designed to affect collective expectations (Public Awareness and Poll)

Conclusion

Our research shows that when social change requires mass coordination, there can be a disjunction between what society really wants (e.g. granting marriage equality) and the outcome (e.g. great social costs for supporting gay rights). The change in social and institutional arrangements will not occur if only relatively few people mobilize. This may happen if people worry about the social costs due to their mobilization – which we show can be high even if a large majority would be in favour of change – or believe that the protests are unlikely to garner broad support.

Social learning is often not enough to promote change. Choices can mask true preferences. Indeed, in one condition, we show that increasing the speed of social feedback (e.g. through new technologies) can prevent rather than promote change.

Two factors consistently helped hasten beneficial change in our study. The first is a common understanding of the benefits from change, which can result from events that attract public attention, opinion polls that aggregate information, or by finding an angle on an issue that appeals to a broad demographic (e.g. marriage equality has proven to be fertile ground for the acceptance of gay rights). The second factor is perseverance. Social tipping in our setting critically depended on a group of leaders who persisted in moving against the established equilibrium, even at great personal cost.

See original post for references

I’d be interested to hear Terry’s view on this as he knows a lot about how this type of survey doesn’t always measure the underlying intensity in which the view is held.

For example, a switch from being pro to anti abortion isn’t always a big jump. Few people go from thinking ‘abortion is baby murdering’ to ‘abortion is a fundamental right’. But a lot of people go from ‘I really don’t like the idea of abortion and I think it should be banned, but I know there are some situations where it may be the only option’ to ‘I really don’t like the idea of abortion, but I don’t think it should be banned as some women really do have no choice’.

In Ireland, there was quite a rapid switch of public view on gay marriage, from strongly against, to overwhelmingly in favour within a remarkably short time, when it was voted in by a 2:1 majority. But so far as I know, the studies show that this apparent change was really just a case of the great majority of people not having given it much thought, and switching from a ‘oh, that sounds a bit weird’ to ‘oh well, people should be able to marry who they want’ when made to choose in the referendum.

That said, there are lots of studies going back decades showing that there are indeed tipping points in societal behaviour – for example from when chucking your waste out your window was considered entirely normal, to when it became considered anti-social. Many Asian countries are particularly good at enforcing this sort of societal change – the supposed conformity of the Japanese or Koreans is really more a reflection of how good their governments are at persuading people that a certain behaviour is not acceptable.

Thanks for the shout-out. I got half-way through the article, thought “I have my own reasons for disliking it” and then hey presto got to your comment! These surveys are very problematic for exactly the reason you give in pargraph one – intensity of preferences. To measure this in a manner that correctly puts intensity into context you can’t do inter-individual variation, nor use rating scales. Even if you somewhat avoid these pitfalls as the article seems to do, temporal changes can be just as tricky: discrete choices confound underlying attitudinal strength (mean on a latent scale of agreement) with consistency of preference (variance – INTRA-individual variance). Do a properly designed choice model and for an individual you can see the betas all go up/down in unison over time – classic variance effect. Odds ratios become huge/small but, crucially, if they are linearly related to “before” then the person is simply surer/less sure now. Their underlying views (means) are likely unchanged.

xy=8, solve for x (means). Can’t be done so the likelihood function has y=1 set by the program to “normalise” it. The program literally “makes stuff up” to give you your means (intensity). You must do two things. First, put the key statement of attitudinal interest in a set ranging from ones you know to be generally disagreed with, up to ones generally agreed with. Multinomial analysis will give you “one solution”. But “the statement of interest” can go “up” not just due to true increase in underlying intensity but because “it’s in the news” or PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE (stated in article) and a 60:40 split in favour can go to 80:20 as variances drop and people are more consistent in their answers. Underlying means might be unchanged.

I won’t risk breaking rules referencing my work, but I’ve shown that, for instance, views on end-of-life care can change means (people move from “throw the kitchen sink at the problem if I’m in ICU” to “pull the plug”) and/or variances (people become much more sure they want plug pulled) once they have seen physically what prolonged intubation does to a person. You MUST properly separate the two types before aggregation else you get biased beta estimates. Suddenly it looks like you have tipping points when you might have no such thing. INDIVIDUALS may have their own internal tippping points but you can’t aggregate them until you have netted out variance effects else your “group tipping points” are just plain wrong – and you don’t even know if they’re too high or low.

Point of clarification. I interpreted your word “intensity” as means but it could be interpreted as variances. Though a very intuitive word, we generally avoid it for this reason, preferring “strength of preference/attitude” (mean) vs “consistency in agreeing with/certainty of agreeing with” (variance).

Your Irish gay marriage example is a good example of a likely variance effect. People thought it through and became more consistent. A statistical “trick” we play, IFF the data are “well-behaved”, is to stratify according to whether individuals have education beyond age 16ish. Calculate beta estimates for each group and plot one against another. They’ll often lie on a straight line but with a slope that strongly deviates from one (post 16 people with much higher betas). Do they have stronger attitudes? NO. The program just assumed they had same variance. 40 years of research have shown that better education/literacy causes people to be more consistent in answers (better at answering consistently), be more able to think through implications etc.

Caveat: If your “certainty” in your views on homosexuality is different from that pertaining to abortion, and different again to that pertaining to (say) gun rights, then the above trick doesn’t work because there’s no longer a single “variance” in the denominator to cancel out.

Thanks for that! Very interesting indeed. Yes, I just meant ‘intensity’ in terms of normal usage, I’m too far away from daily use of statistics to remember the correct terminology.

“. . . this type of survey doesn’t always measure the underlying intensity in which the view is held.”

Correct, because the ‘underlying intensity’ is a condition prior to the ‘tipping point’, a subset; it and any number other factors — subsets — underlie the reality prior to the tipping point. But no number or combination of subsets, would prove or disprove the validity of the tipping point 35% threshold; since these are tangential to the primary assertion/argument, they would not, logically, be taken into account.

Hmmm. I think that the long green line to Loving v. Virginia–and note the year of the decision, 1967, which is 13 years after Brown v. Board of Ed–undermines the argument of this piece. The mix of class and race in the U.S., admittedly an exceptionally toxic brew, means that tipping points that involve race are complicated most likely by a tenacious minority along with Martin Luther King’s famous “moderates” that benefit socially and economically from racism.

Further, the sudden upward sweep for marriage equality doesn’t account for the long history of agitation–going back to the early twentieth century, possibly even into the nineteenth century, or that the solution involved treating marriage as a contract, which simplified the situation quickly and legally.

So: Some doubts, as Yves Smith also points out in the head note.

Progress isn’t natural at all, and successful elites will put a halt to it if they can.

Russian Czar’s were very successful, and serfdom still existed in Russia into the early 20th century. The Russian aristocracy wanted for nothing, and there was no reason to change a thing.

“Why Nations Fail” is a good book on how those at the top don’t like progress.

Even in the poorest countries, those at the top are quite happy with the way thing are. You will find they still live in luxury and leisure and everything is working fine for them.

Progress is always a struggle between those below and those at the top.

The Magna Carta represents the triumph of those below, the Barons, over those at the top, the Absolute Monarch, who was quite happy with the way things were. Royalty spent centuries trying to get back the power they had lost with the Magna Carta.

Progress involves wealth and power becoming less concentrated.

Those at the top like progress in the reverse direction back to when wealth and power were more concentrated.

The progress in the Keynesian era was not welcomed by many at the top and they soon set to work.

Faith in free markets was at a low ebb in the 1930s, with only a few fanatics like Hayek able to maintain their beliefs. He was busy at the LSE and couldn’t see any problems at all.

In the 1940s, Hayek put together his theories of the markets being a mechanism for transmitting the collective wisdom of market participants around the world through pricing.

It was never going to get into the mainstream until nearly everyone had forgotten what happened last time they believed in the markets.

The Mont Pelerin Society was formed and they worked away behind the scenes thinking of new ways to get us back to old ideas.

When Keynesian thinking began to fail in the 1970s they were ready to pounce on this opportunity.

They played a blinder and combined old economic ideas with socially liberal ideas.

How does this combination work?

Inequality exists on two axes:

Y-axis – top to bottom

X-axis – Across genders, races, etc …..

The traditional Left work on the Y-axis and would be a problem when you want to increase Y-axis inequality.

The Liberal Left work on the X-axis.

You can increase Y-axis inequality while the liberal Left are busy on the X-axis.

You are allowing progress on the X-axis, whilst going backwards on the Y-axis.

I think you neglected to mention that your y-axis is logarithmic.

I agree that looking at real mechanisms that are purposefully created to be “in place” when the time comes… is one way that has actually manifested “changes” . The story of the mount perelin society and a group of advocates all having similar values, and creating the infrastructure, of academics,think tanks, publicity/press,etc…and real political connections…. all completely kept alive by ideas and “somebodies money” that wants these ends… whatever the means.. creates a” community of interest “, in the making of movements. And “group think” becomes the self;supporting trellis these ideas find in the perennial source of new personalities that “use the advantage given by the connections of like minded people” to their advantage.

it seems the founders of that group of early neoliberals, had the realistic vision to know that them starting this in 1947, would not materialize any velocity before a generation, and they were right.

This is akin to what carroll quigley details in his “Tradgey and hope”, about the creation of the british roundtable in 1891, which directly expanded into the creation of the council on foreign relations and the institute of international affairs… and SO many others… of creating networks of powerfully connected individuals who all “think similar enough” to “be on the same team”…

it also seems to be like the founding of the jesuits, who were to counter the reformation, and the thinking against the catholic church.

loyola and his jesuits engaged in “learning against learning” they used causistry and equivocation,science and technology… as the lip stick on the pig. to remain relevant… and remain in control of the narrative.

Anecdotally, I think that the reason why broad sweeping changes in things like gay rights and other social areas were achieved relatively quickly, is because a lot of the corporate institutions that influence and donate to both parties in our political system do not really care about social issues one way or another as it does not affect their personal wealth or profitability. Therefore, they largely ignore the political battles in these areas.

However, things like Medicare For All, labor rights, and affordable housing would cut into their ability to make the obscene profits that they do and challenge corporations’ ability to maintain the authoritarian control over the employees that they currently have. Therefore, even though these things are also overwhelmingly popular among the populace, our political leadership has not budged in making them a reality and will continue to stall on these fronts for the forseeable political future. The political power that corporations have in their opposition to the above is formidable, and there is also the fact that they have figured out that they can cloak themselves in a shroud of faux cultural awareness to further dismantle any progress on labor rights and wealth inequality.

Yes. The political power of corporations is enhanced by a political structure (Congress) that demands 60% approval in the Senate to get legislation passed. The other issue is that neither political party is effectively “progressive” (compared to the electorate).

SSM and abortion are early victories of Idpol, which began creeping in in the late 60’s. Idpol is great, because it creates a great distraction from say, class struggle. If you can keep people worked up about Furry Story Hour or the flavor the day, they won’t notice if you reinstitute serfdom.

That being said, I don’t think you could practically ban abortion any more than you could ban pornography in Western countries. Its too intregral to the system of modern living.

Been reading “These Truths” by Jill Lapore

One of the surprising things this book brings to the fore is that the political parties have changed their minds on many of the issues that we currently find ourselves divided by.

For instance, the Republican party endorsed women’s rights, including the right to choose, up until Phyllis Schlafly showed them how powerful the issue could be as a wedge.

IIRC, Up until the early 1970s, the republicans were champions of women’s rights, including access to abortion.

(Republican women were a major power in the party, they fought Schlafly, but lost.)

All of this coming under the heading of political changes brought about by the introduction of computers to allow analysts to segment voters.

Pat Buchanan convinced Richard Nixon to quit supporting women’s right to abortion by explaining that the number of catholic votes he picked up, outweighed those lost.

Computers made these calculations much easier to make, and so the calculations were made, and party platforms changed.

Yet, people still see fit to be publicly associated with and to provide material support to these corporate terrorist organizations.

(Don’t mind the language, just trying on some of the theories of the article…)

What I’m pointing out is that inflection points can be synthetic as well as organic, or natural, if you like.

Nixon’s use of the “Southern Strategy” prompting an inflection where the South switches to voting Republican, after years of Democratic dominance, or Phylis Schlafly more or less single-handedly turning the Republican party against women’s rights, the ERA and abortion rights, being examples of synthetic inflections.

I think the authors of this piece are mainly talking about ‘natural’ inflection points, not those those that are the result of tactical efforts.

I am curious about the word intervention, used frequently by Andreoni et al. above. It does not appear to be defined in their article but perhaps it is a term of art in economics and management studies, the disciplines to which the authors are said to belong. To me, a common-sense definition would be ‘the application of state power or force by its ruling class’ in which case the production of numerous graphs would be an expected immediate outcome, but would cast considerable doubt on the direction of the progress mentioned.

It is a term of art, and it should be widely understood not to impose lay narratives onto terms of art, especially not in this case where it plays into neoliberalism’s hands by ignoring and therefore blessing private, corporate power, which is (at best) a norm currently contested.

The American Heritage Medical Dictionary says:

1. The act or process of intervening: a nation’s military interventions in neighboring countries; a politician opposed to government intervention in the market economy.

2.

a. The systematic process of assessment and planning employed to remediate or prevent a social, educational, or developmental problem: early intervention for at-risk toddlers.

b. An act that alters the course of a disease, injury, or condition by initiating a treatment or performing a procedure or surgery.

c. A planned, often unannounced meeting with a person with a serious personal problem, such as addiction, in order to persuade the person to seek treatment.

In the article we’re discussing, the usage of the word intervention seems fairly well aligned with common-language definitions and some of the medical definitions as well. Maybe it would help if we knew who or what the intervenors are or would be, and what means of intervention are proposed, and who or what initiates, designs and governs the project of intervention. I don’t see corporate power or neoliberalism as norms, but rather institutions or practices upheld by explicit state force, which makes the question of who the intervenors are, who are to be intervened upon, and what means are to be used at least interesting — to me, anyway.

on an anecdotal and thoroughly lay anthropological level, i was witness to such a change in rural texas … specifically the acceptance of overt public displays of racial animus, from n word up to public physical harassment

all of that had become unwelcome in public by the time of trumps revanchist turn

saying the n word … even way out here where there’s only one. tiny black family… just wasn’t done

like peeing on the bank floor

similarly with acceptance of gays

a lot of this had to do with simple exposure… in our case, not to blacks but to hispanics…when your sister marries a brown man and he turns out to be just a person and not the cartoon villain you thought, your mind can change.

again, similarly with gays… cousin comes out… initial freaking out… then settling into new normal when sky doesn’t fall

sadly, i think that while trump et al have led a retreat into the cave, the wokeratti have been effectively chasing them into that cave

Doesn’t the wokeratti, in spite of its self-righteous tone, simply tell the cave dwellers to stop being racist toward black and brown people and that its wrong? And what would be wrong with telling them that such bad behavior leads to the denial of civil rights, civil liberties, and in such cases, death for black and brown people? Would telling them that’s it’s ok to be racist lead them from the cave, in addition giving them better 99% economic policies? Would the better economic policies make their racism disappear? Maybe instead of blaming the wokeratti, they should own their behavior?

it’s the difference between taking someone by the hand, where they’re at, and leading them to such enlightenment…and scolding them incessantly(“deplorables”), causing them to double down on the very behaviour one wishes to amend.

it’s been frustrating to watch….given the slow but steady progress i outlined….and for someone like me, it feels like decades of patient, generally one on one, work, has been suddenly undone.

right or wrong, the perception is one of hostility and “lording it over”…which causes a reactionary retrenchment.

you can’t legislate…or otherwise force…a sincere change of heart.

the totalitarian features of the more extreme wokeism are counterproductive…and if you have an entire media bubble bent on accentuating grievance and a laser focus on “cancelling”, whether actual or perceived, it makes it all that much more difficult.

Humanism and the above mentioned exposure is what is called for…and this goes for the more extreme Metoo, too…abandoning due process, and the preemptive assumption of guilt, due to one’s physical appearance and/or anatomy…

but by all means…keep yelling at them how irredeemable and inherently evil they are.

I’m sure they’ll come around.

Exactly!

How long do we have to wait for them to progress to treating people who don’t look like them as equals? The civil rights bill passed close to 60 years ago and they still can’t deal with progress???

James Baldwin had a great quote for this:

“What is it that you wanted me to reconcile myself to? I was born here more than 60 years ago. I’m not going to live another 60 years,” he said. “You always told me that it’s going to take time.”

“It’s taken my father’s time, my mother’s time, my uncle’s time, my brothers’ and my sisters’ time, my nieces and my nephew’s time,” he continued. “How much time do you want for your progress?”

I think these sorts of actions are better judged by their effect, rather than by their stated intent.

If you say you want to make friends, but go around saying and doing the things that make enemies, then either you are a disturbed individual, or you are really up to something else.

And since most followers follow their leaders, and their leaders seem to be setting these sorts of examples…

No, the wokeratti calls Bernie Sanders racist for supporting economic uplift for poor people instead of reparations for slavery.

No, the wokeratti demands to know ” what that will do about racism and sexism” when Sanders says the banks should all be re-Glassed and re-Steagalled. ( Hillary Clinton was the public face of the wokeratti in that debate).

Figure 1 at only 624p width is borderline illegible on a large monitor.