By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

“I have but to close my eyes and I hear your Duke telling me that real estate is always gained and held by violence or the threat of it.” –Frank Herbert, Children of Dune

“If you have one hundred dollars, and I have one hundred dollars and a gun, then I have two hundred dollars.” –Apocryphal

Michael Heller is a Professor of Real Estate Law at Columbia Law School. James Salzman is a Professor of Environmental Law at UCLA and UCSB. Together, they have written a coruscating book on property: Mine! How the Hidden Rules of Ownership Control Our Lives. Whether “Because markets” is the simple rule by which you lead your life — or, perhaps, even more so if it is not — you will find Mine! a fun and engaging read. (It’s odd that earlier today I wrote about a mine, the Warriot Met coal mine, and now I’m writing about what’s mine.) It’s a great book to read on the airplane, and indeed I read it while traveling. Now, I didn’t grab Mine! off the bookstore stack because of Cass Sunstein’s blurb — “A fascinating discussion of what ownership is, what it isn’t, and what it might be. It’s immensely clarifying, beautifully written, and perfectly times–and it might improve the world to boot” — but because when I gave it the random opening test, I found a polished anecdote on shooting down a drone, which — stands athwart history, yelling Stop! — I am here for.

Columbia’s public relations department describes the “central idea” of the book:

[The authors] set out to write “Freakonomics [more here] for ownership” to show readers how ownership affects every aspect of their lives, every day. “We swim in ownership rules that are omnipresent and invisible at the same time,” says Heller, a preeminent scholar of private law theory. “Ownership is about who gets what and why. The central idea of the book is that what people consider ‘mine’ is not something fixed or natural. It’s always a choice and always up for grabs.”

(Indeed. As the Bearded One once observed: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”) Publisher’s Weekly unpacks how, according to the authors, people “consider” what is theirs:

According to Heller and Salzman, there are only six stories that “everyone uses to claim everything.” They walk readers through each of these concepts, contending, for example, that foraging laws, copyright regulations, and mineral extraction rights all involve competing ownership principles of labor (“You and you alone deserve to reap what you sow”), possession (“This is mine because I’m holding on to it”), and attachment (“It’s mine because it’s connected to something that’s mine”). By identifying these principles and understanding them as rival stories rather than hard-and-fast rules, voters and lawmakers will be better equipped to deal with issues such as climate change and the social costs of the sharing economy, according to Heller and Salzman.

Indeed, Mine! is a fine example of what the Times dubs “pop law.”[1] In this post, I’ll start with the six stories (or “maxims,” as Heller and Salzman call them. Then I’ll look at one of the maxims (dubbed “attachment”), giving examples of it. Finally, I’ll look what I think is the central program or agenda of the book: “Ownership design,” which is what the authors, were they consultants, would be selling. Because there are too many words for me to type, I will quote great slabs of the book in the form of screen shots. I apologize in advance for their lack of rectilinearity; they were the best I could do with the iPad.

Let’s start with those six maxims:

“all the ways scarce resources initially came to be owned” is an expansive claim. It is also false. I don’t believe that (Nobelist) Elinor Ostrum’s discovery of “common pool resources” can be reduced to these rules, because CPRs permit “Collective-choice arrangements,” which are by definition not “mine” but “ours.” (Ours! would also be a great title for a pop exposition of a different kind.)

You will have noted the words “Are Wrong” in the heading above the maxims. Here is why those maxims are wrong:

They’re wrong, I would say, because they’re not supple enough to meet the needs of the present day. Fair enough. (I’ll note in passing that perhaps the binaries of the past are not all that: The subjects of the Civil War’s Port Royal experiment, for example, having picked cotton for as slaves, had no particular desire to pick cotton as wage slaves, but would have preferred to grow good on their own land for themselves and for sale; I don’t know enough about African concepts of land-ownership to know whether they conceived some or all of “their own land” to be held in common.) Nevertheless, the maxims are “right enough” to have a powerful hold on the imagination, as the authors show with many examples.

Let’s look at one of the maxims: #4, “My home is my castle,” which the authors dub “attachment.”

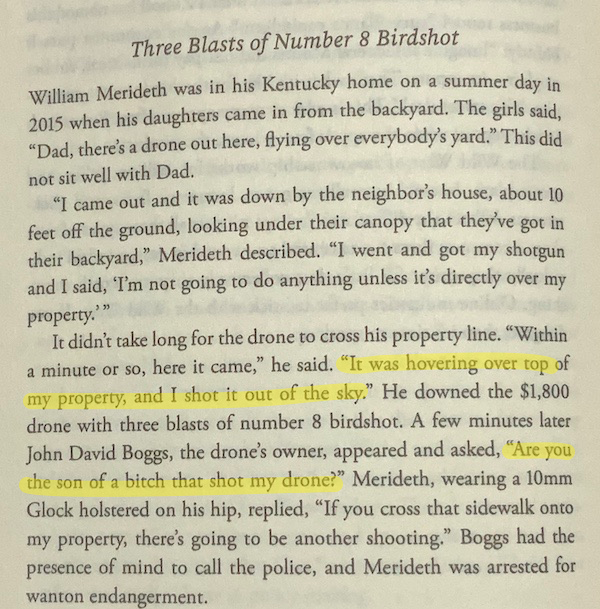

“It’s mine because it’s attached to something mine.” Here is the drone example:

In this case, the hovering drone is conceived of as invading Merideth’s “castle,” since Merideth mentally attaches his airspace to his house. (There are all sorts of reasons why this property design is “up for grabs,” but that’s Merideth’s concept, as it would be mine if one of those horrid robot dogs crossed my property line; I’d try to trap it, or entangle it, or short it out. Git!

Here is an example of the attachment principle applied, successfully on a larger scale. The setting is New York’s wonderful, pristine water supply, dependent on keeping water sources in the Catskills clean and pure. But what happens when developers start encroaching on those sources?

So, New York makes a deal with the Catskill landowners: New York pays the landowners as if the landowners owned the “environmental services” “attached” to their land. If Heller and Salzman are to be believed, the scheme worked. And there are 550 active programs like this around the world (which is a very small number, as is $42 billion, which is less than half Jeff Bezos’s fortune, and less than one-tenth of Bitcoin, at least right now).

This — “ownership design” — is to me the heart of the book:

I have also been saying — as I try to conceptualize the biosphere by perambulating through it — that the point of identifying ecological or environmental “services” is to commodify them. Here we see that, and we also see the method of doing so: Ownership design. At some point, I’m going to encounter the original sources of these ideas, and go to work on them.

Mine! is a wonderful example of the glittering, glamorous neoliberal mind at work. For now, I don’t know enough about property and/or the biosphere to make a serious critique, so my reactions are aesthetic and intuitive. Aesthetically, the idea that anyone Cass Sunstein would give a blurb to will be charged with saving the planet chills my blood and gives me the grues. Intuitively, if as Hayek urges, the market is a wonderful information processing machine, then what is nature? Surely the market — for all its ownership designs — is an 8088 compared to nature’s quantum computer? I doubt very much that “services” can be defined precisely enough so that the services that are paid for — ok, let’s just go ahead and call them “rented” — do not overwhelm and distort services that are not paid for, and may even be unknown.

NOTES

[1] On baby’s first words, here is the first sentence of Mine!, on page 1:

Mine! This primal cry is one of the first words children learn. Toddlers in sandboxes shout it out during epic struggles over plastic buckets.

Here Salzman expands the claim to “all cultures”:

In every culture, “mine” is one of the first words that children speak. On playgrounds, all you hear is kids shouting “mine, mine, mine!” Ownership rules the sandbox.

Ditto Michael Heller:

“Mine!” is a primal cry that ricochets through sandboxes and playgrounds around the globe. “It’s one of the first words children learn,”

So I checked the notes, which Mine! is enough of a work of scholarship to have. The “baby’s first words” claim cites to an article in Parents Magazine (!):

“My and mine are some of the first words children use,” explains Peter Blake, Ed.D., a developmental psychologist at Boston University. Although they’ll say Mama and Dada first, they quickly realize that they can claim an object simply by using language: my ball, my dog, my cup, and so on. What a cool trick!

(Note that Blake does not make this claim for “all cultures.”) Now, Blake doesn’t explain how he knows this. But as it turns out, at the very minimum, “one of the first words” is doing a lot of work, as is “primal cry.” From the Atlantic. “The Mystery of Babies’ First Words“:

In American English, the 10 most frequent first words, in order, are mommy, daddy, ball, bye, hi, no, dog, baby, woof woof, and banana. In Hebrew, they are mommy, yum yum, grandma, vroom, grandpa, daddy, banana, this, bye, and car. In Kiswahili, they are mommy, daddy, car, cat, meow, motorcycle, baby, bug, banana, and baa baa.

So, “one of the first” is at least eleven, eh? Further, family ties are clearly more important than property, if primacy is to be equated with importance. Finally, I have the wicked urge to wonder if children screaming “Mine!” are perhaps over-represented in the playgrounds and sandboxes that Heller and Salzman, and their professional comrades, frequent, along with the reviewers who find this factoid so immediately intuitive and appealing. One can only speculate why this would be. Genius to make that sentence the first, though. Everybody quotes it.

Yes, the cry of “mine” was the first thing that jumped out me. That is, is their claim actually true? With my daughter it was ‘mommy, daddy, hi, no, etc.’ I don’t remember hearing the “mine” cry at all (in the context of claiming some kind of ‘ownership’ of something, protecting it from others). Even to this day, and she is pushing 7 years old.

I’m glad you looked up those example of first words. Very interesting

The whine I heard from my kids was always, “It’s not supposed to be this

way.” I think that about covers it for everyone.

I recall having the same conversation with both “my”sons at about 8 years. He would claim something was his – not mine – and I would argue that he belonged to me, so everything he owned was mine. That did not satisfy but it ended the disputes, since I didn’t actually enforce my rights. It must have worked . They both grew to be good capitalists.

That function, dispute resolution, seems to be the the real reason we have so many rules in this area. Yes it’s ultimately about domination and control but it all goes down easier if the answer to most ownership questions is obviously covered by some rule. And for people who won’t accept anything but a decision by higher authority we have judges in black robes.

Fairness is often an early concept

Followed pretty quickly by realizing there is no fairness in this world. My teenager has learned that even more this past year.

The skepticism is justified. Children don’t even have the idea of object permanence until they’re around two years of age. There’s nothing “primal” about screaming “mine.” It’s a product of culture, and not close to being one of the first things learned even in our capitalist culture.

This fits with my experience too. I always found that the “mine” discourse with kids emerged from (PMC) parents trying to socialize their kids – “Don’t take that shovel, it’s Max’s. Here is yours.” (Similar to the “sharing” toys discourse, which is also fundamentally tied to ownership notions, not to mention early reinforcement of class distinctions between people like “us” who “have” and the poor unfortunates, whose younger members of course have no manners because they are, basically, sub-human.) I may be in the minority in thinking that this is mostly well-intentioned parent behavior, but there is no doubt it reinforces the neoliberal outlook in the very young.

I’ve also noticed it comes from younger kids getting consistently ‘dispossessed’ by their elder siblings who often aren’t particularly considerate of the younger kids.

So, yes, that would suggest the possessiveness is being bred into the kids.

My home is my castle unless I don’t pay the property tax and then it becomes the county’s castle–or the bank’s if I don’t pay the mortgage

I do agree that property rights are at the root of much of what gets discussed around here and perhaps the capitalism versus socialism debate itself. More like this!

I actually think that a lot of the urge to gain property is rooted in a yearning to insulate oneself against instability and risk of poverty and the lack of control in modern life.

Ever notice the large number of people who have incredibly mundane answers to questions like, “what would you do if you won the lottery?”

Stuff like, “I’d pay off all my debts” comes out a lot of the time and the imagination often doesn’t go much further.

That’s not the answer of someone fueled by greed, it’s someone terrified of poverty.

My son is 3.5 years old. The other evening, I overheard him say to himself “My book!”

“My” is roughly word 500, after the determined memorization of multiple First 100 Animals books and reaching the point of speaking in full sentences. My son has been saying “Humpback whales!” every time something even remotely like one shows up on a screen or a page for months now. I’d be concerned at this point if he hadn’t learned the concept of “mine” and “yours” of course – especially since we are working on the concept of sharing – but it’s hilariously telling that the neoliberal mind considers it on the same level as “mama/dada”. I think I’ll pass on this book.

Just wanted to throw in a +1 for your last paragraph there, Lambert ;)

John Locke?

I especially like Cory Doctorow’s take on it

That’s a good article although of course itself a bit simplistic. The patent regime does try to distinguish between “ideas” and specific execution. Doctorow defends the open availability of his books but would that also apply to actual plagiarism and someone claiming authorship of large passages that are exactly the same? Perhaps his reply would be that only the ideas and the “zeitgeist” matter rather than the specific words.

I think many of us here would agree that “intellectual property” has become a grift as much as a real thing. It’s a made up concept that didn’t used to exist and is defended, as are Locke’s flawed arguments, in the name of practicality. When IP becomes a social negative that defense is nullified unless you are indeed a Randian.

I think Doctorow has been consistently pragmatic on so-called IP laws, preferring to refer to them as (limited) government-granted monopolies.

I can’t speak for him but I doubt that you’d catch him in hypocrisy.

Never hypocrisy and I’m all for his championship of “the commons” since I make so much use of it (typing this on Linux).

Since you mention Linux as part of “the commons”, in a thread about ownership, and the way “the commons” are constantly converted to private benefit, I have to object. Linux is most certainly *NOT* part of the commons. It is carefully and thoroughly protected from that fate through the conscious application of legal theory, and further protected by a huge chunk of thought and ongoing legal effort. I refer to the idea of “copyleft”, whose name makes it automatically and deliciously suspect in the warped and bifurcated world in which we find ourselves.

The specific implementation of copyleft that applies to Linux (and probable to the tool you actually used to do your typing) is the GPL v2, deliberately chosen by Linux’s original author. I believe the recent version of the GPL does not meet his approval, so there is yet another example of improving something ’til it is broken.

If you are interested in actually understanding the process of keeping ideas open, and resisting the insidious process shown in the subject book, we could do worse than a hat-tip to Bruce for a most-salient reference to a certainly not simplistic essay. Here’s another good place to look to begin to understand some of the complexities:

http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/

You should note the long and steadfast ties Doctorow has to the FSF – for example:

https://www.defectivebydesign.org/blog/doctorows_novella_unauthorized_bread_explains_why_we_have_fight_drm_today_avoid_grim_future

wow. this encapsulates an idea i’ve had for some time now – that private “ownership” of things which are indeed truly public in nature (as in the public at large suffers though irresponsible or inconsiderate uses) is deeply m at the root of our capitalistic system which doesn’t work like it could as its foundation is thusly so weak. It’s been argued to be the “best” system devised to date, but sustainability isn’t being measured as a success criteria, is it?

“Public cost, Private gain” has amplified the last 20 years as well, exacerbating the error.

Thank you for posting this.

There’s a few privately owned Giant Sequoias out there, but owing to socialistic tendencies largely, everybody ‘owns’ all of the ones in National Parks & National Monuments. They’re very much mine-and yours, ah that sweet smell of group ownership, with money never entering the conversation.

Money may well enter the conversation at some future date when the Congress decides to sell the groves to private interests who will then charge a fee to visit them.

I’m not too worried about the prospect, the last one that ‘sold’ was the Alder Creek grove, which Save The Redwoods League purchased for $15 million via donations in late 2019, just in time for half of the grove to burn up in the Castle Fire last year.

It’s probably only coincidence that Professor Saltzman teaches at UCSB. In the 1960’s another UCSB professor, Garret Hardin, explored this topic of what is “mine” and what is shared in his essay, “Tragedy of the Commons”. (Many think he coined the term—he did not.)

I listened to Hardin’s oral presentation on this topic in a UCSB lecture hall, then. It’s an issue that needs to be resolved quickly or lifeboat earth will sink.

> Garret Hardin, explored this topic of what is “mine” and what is shared in his essay, “Tragedy of the Commons”.

Elinor Ostrum explains why the Tragedy of the Commons is problematic at best. See here at NC

Thanks for the link, Lambert. I was unaware of that discussion—must have been away on a ski trip.

I mentioned “Tragedy” not as a solution to the dilemma of the commons but that 50+ years ago the issue of what’s “mine” and what’s “ours” was hotly debated. (The year after “Tragedy” was published the Santa Barbara Oil Spill occurred (1969) and the environmental movement began.). That our government can’t seem to recognize that sustainable regulation of the commons is the solution to pollution is frustrating.

The Appleton and NY cases are applications of the (in?)famous Coase Theorem. In situations where information is easy to obtain and verify, creating property rights will result in people taking proper account of externalities in their decisions. It works in information-easy environments but perhaps not so much for the cases that Ostrom was working on.

Pistor, “The Code of Capital” is a remarkable book about the way the law works to ensure the dominance of capital by its ways of defining ownership. The author is one of the experts in the field, but has written the book for a non specialist audience. It’s still a demanding book, though, but it’s well worth the effort.

In the history of “invention” or “entrepreneurship”, one of the driving forces of economic history, ownership almost always ends up with someone on the business and legal end dead set on gaining control, and the actual inventors are sometimes frozen out entirely. Examples include Edison and Tesla, Rockefeller and the Minnesota mines, the Singer sewing machine, Bill Gates and Microsoft, Henry Ford and the automobile.

“The Code of Capital” is excellent, especially for its story of how the powerful bend the law to their purposes where KEEPING their pelf is concerned.

> Pistor, “The Code of Capital” is a remarkable book

One more damn book to read!

I read of a case of “earned” ownership in the book “Grapes of Wrath” though it is hard to classify. In it, it described how law enforcement back then took care to destroy any small crops growing that people had planted to feed themselves. The problem was that once a patch of ground had actually fed a family, that there was now a bond between that family and that patch of land that they would actually fight for now.

1. About language :

Mathematical language rests on a conceptual construct that starts with unproven axioms from which are derived theorems that are used to justify theories… In analogy human societal languages rest on civilizational-axioms and worldview-theorems that are imprinted in our subconscious and foster epistemological habits. The thinking, behavior, and actions of the individuals are driven by such habits and in that sense the free-will of the individual is largely an illusion. The illusion is indeed not absolute, for, it is possible to deconstruct it and to gain access to free willed decisions for oneself but this implies hard work, focus, and blocking out of one’s mind the incessant calls from society. That also means that vanquishing the illusion of free-will is largely an illusory thought. Only the wise go there. But they are rare…

What I try to convey here is that language is a reflection of the epistemological habits of our civilization and of our societies and those habits are stored and acted upon by the individual’s unconscious. The notion of “mine” and more generally of “ownership” are such habits that vary from one civilization to another…

2. Reason as a habit

Modernity is rooted in “the reason that is at work within capital” that emerged sometime in the first part of the 12th century in South-West Europe where Christianity had nourished a ground that proved to be particularly fertile for its shooting. The reason thus rapidly forced a particular vision of “me me me”, “mine”, and “ownership” … first on Western Europe, then its colonial extensions, and finally on the whole world.

The application of the reason by “long distance” merchants procured them immense richness that they converted in all kinds of visual signs (architectural and artistic) and over 5 to 6 centuries those signs had attracted the envy of all in Western Europe including the monks who thus were drawn to tweaking technical solutions to satisfy the need for import substitution goods that the mercantile policies of the British crown had unleashed in order to avoid the transfer of the country’s precious metals to India and to China… This by the way is what launched the industrial revolution.

When speaking about reason we immediately think about rationalism. But the fact is that rationalism was the systematization of the reason that emerged in the 12th century. This whole historical process has been encapsulated in one word : “capitalism”. But the word has unfortunately lost the explaining power that led to its use…

You write that “in the first part of the 12th century in South-West Europe where Christianity had nourished a ground that proved to be particularly fertile for its shooting.” (whatever that means)

In the 12th century, southwest Europe, namely the Iberian Peninsula, was only partly Christian. Most of it, and the richer southern part, was Muslim.

I think that property and private space are concepts that get confused. Someone who is flying a drone above one’s house might be violating, not an ownership, a castle or whatever, but the private space and life of someone else, possibly having a nap in the garden, enjoying a meal with friends, playing with children etc.

Violations of the private space (not ownership) and possibly the confidentiality of one’s private actions is nothing for which I have sympathy. In the example above of the 3 blasts against the drone I would have arrested both, the owner of the ‘castle’ and the owner or driver of the drone.

Yes, there are much wider concepts, which no doubt change radically from legal system to legal system. In the UK, for example, your ‘ownership’ does not extend belong ground – often mineral rights were maintained by the former aristocratic owners (when I worked in the West Midlands in England, every legal deed noted that Lord Dudley or similar owned all the coal and iron beneath the persons garden).

Then additionally there are restricted rights – such as if you have, for example, an historic structure on your land your ‘ownership’ rights can be very restricted.

Even before drones, there was always a question over overhanging structures. I was told in the UK that you have the right to cut the branch of a tree over your garden or house, but you must offer the wood back to the owner.

In Ireland and the UK there are entire libraries of legal books dedicated to issues like the ownership rights to party (shared) walls. In Japan they seem to avoid this problem by leaving minuscule gaps between neighbouring buildings. I’ve seen huge structures in urban areas in Japan with literally the gap of a few sheets of paper between them.

This is also the case in the USA, especially in the east, where land ownership records go back a longer way. In Pennsylvania it became a huge issue with fracking, since some owners found out quick that they had no rights to minerals on their property.

Incidentally I don’t have “fossil” rights on my property. Better no find a T. rex skeleton in the garden!

A few year ago, I briefly toyed with the idea of purchasing some rural, undeveloped land in Ohio. I told a real estate agent that I was only interested in parcels that came with mineral rights. His reply? “There aren’t any left.”

(I did not go further and try to verify this.)

Indeed, in the UK your ownership doesn’t necessarily even extend to the ground itself, because of the distinction between the freeholder and the leaseholder. In Europe, the system of “co-ownership” of apartment buildings creates its own hilarious confusion.

When I saw the title I immediately thought of CB MacPherson and his theory of possessive individualism.

Privacy is the key here, I agree. Would it be appropriate for someone to stand in the road in front of my house dangling a 50 foot pole with a camera on the end over my property? Of course not. They’d be told to leave.

Seems like people think that as long as the pole is invisible it’s okay.

I’m supportive of Mr Birdshot.

At our previous house – within the 5 km exclusion zone of the local airport – we had several incidences of a drone hovering in our garden, about 6 feet off the ground, while we were having dinner outside.

We don’t have guns in Europe, but I would have considered a well-thrown stone and when the owner whinges report him to the airport and the police.

Lots of sympathy for Mr Birdshot

Traditionally in the US (and English) systems, ownership of land included ownership of the ground to the center of the earth and of the air above the ground. That has been whittled away through the years, but you still own the air above your home up to navigable airspace (to be defined). So the person flying a drone above one’s house, is in fact violating ownership if they are flying low enough to be brought down by birdshot.

The motivation to have a “mine” is rooted in territorialism.

Yesterday I was stung by a wasp who was defending its nest (territory).

The chickens defend their perch, and their place in the pecking order. Same with the goats; they defend their pen from encroachers.

The point is that this impulse to define, acquire and defend territory is very deeply rooted in biological architecture. Top to bottom, it’s built-in, genetically-expressed behavior.

The root of politics is a fight over “territory”, and the rules of the game are strong dominate weak.

Social contracts like constitutions are mechanisms whereby the weak defend themselves from the strong by banding together to become strong(er). Same for law, and of course laws are under constant pressure by the strong to make those laws favor the powerful.

One theme in this discussion is “what are the ownership rules for the commons”. A commons implies two entities: “I”, and “us”.

What are the allocation rules for defining what can belong to an “I” .vs. what must belong to the “we”? And who, exactly, is the “we”? Humans, or some other entities as well?

Lambert’s comparison of what humans understand (we “get” the architecture and functionality embodied an 8088 microprocessor) .vs the Quantum Computer level of complexity of the natural world is quite apt.

Every time we draw the property-ownership boundaries, we mangle some vital and yet poorly understood operational aspect of the Natural World. So that means our definition of what is “ownable” needs to be based on how the natural world actually works.

American indians were astonished – incredulous – over what the settlers wanted to “own”. We chalked it up to their being uncivilized and primitive.

There are some people, and maybe even some cultures, whose impulse to acquire territory is so strong that they’ll happily generate any rubric necessary to enable that acquisition.

They’ll invent entire religions, social hierarchies, and behavior norms – including warfare – to get the job done.

Wow, quite a discussion already.

A historical discussion of property would have quite different principles. By the late neolithic and throughout the Bronze Age (3000-1200 BC), land tenure was the main property, and it was ASSIGNED in proportion to its ability to enable the holder to (1) perform corvee labor duties, and (2) serve in the army; or (3) pay taxes of equivalent valuation.

the LIABILITY came first, and was the organizing principle; the asset ownership was a derivative.

The major dynamic expropriating smallholders (appropriating their land) was by creditors foreclosing. And that was kept only temporary, through the Bronze Age.

this is why economists don’t study ancient history (or even modern history, for that matter.)

As for Ms. Pistor, when I asked her about the role that debt and foreclosure played, she just looked bewildered and couldn’t fit it into her system.

I can’t really respond to your rather sketchy criticism, but “debt” has something like a 100 footnotes in her book. And she oesn’t go back to the Bronze Age.

So the concept of attachment did not go anywhere near what I expected. I was thinking more along the lines of emotional attachment (as in this thing is meaningful to me). I lived in several communes in my youth and worked in a collective but we all had our favorite tea or coffee cups. I’d be interested to see how these authors deal with and the notion of “held in trust”.

Deal with gifting.

Somehow I lot a word

For the record, my son’s first word was “bird”, because bird is the word.

Depression era, a man looks out his upstairs window and sees a man sleeping in his front yard.

He yells, “Get off my property.”

“How’d you get this property?” the man in the yard asked.

“From my father,” was the response.

‘Where’d he get it?”

“From his father.”

“Where’d he get it?”

“He fought it from the Indians.”

“Come down here. I’ll fight you for it right now.”