Yves here. It feels a bit disjointed to have such an important issue as hunger and malnutrition presented as bloodless “food insecurity”. But as the headline indicates, it is remarkable how many households aren’t getting adequate rations, yet the press has largely chosen to look the other way. It appears that, because Lenin said it, our supposed leaders have chosen to ignore that “Every society is three meals away from chaos.” Assuring that most people are adequately fed is fundamental to political legitimacy.

We’ve posted on how Covid increased food insecurity in the US (see Hunger Rises Dramatically in America from May 2020 and Need Amid Plenty: Richest US Counties Are Overwhelmed by Surge in Child Hunger from this March as examples). The post below gives a picture of how acute food insecurity has become around the world.

By Christian Bogmans, Economist, IMF; Andrea Pescatori, Economist, IMF; and Ervin Prifti, Senior Economist, IMF. Originally published at VoxEU

Global food security is being threatened by the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictive measures to control it. Jammed food supply chains, falling incomes for some population segments, and rising food prices are placing food out of reach for millions of individuals. This column discusses the short-run relationship between food (in)security and income and food prices, and the implications of the current economic crisis for global hunger. The pandemic’s economic fallout risks setting us back a full decade on eliminating undernourishment, especially in low-income countries. Governments should strengthen social safety nets for the most vulnerable to keep inequality in check.

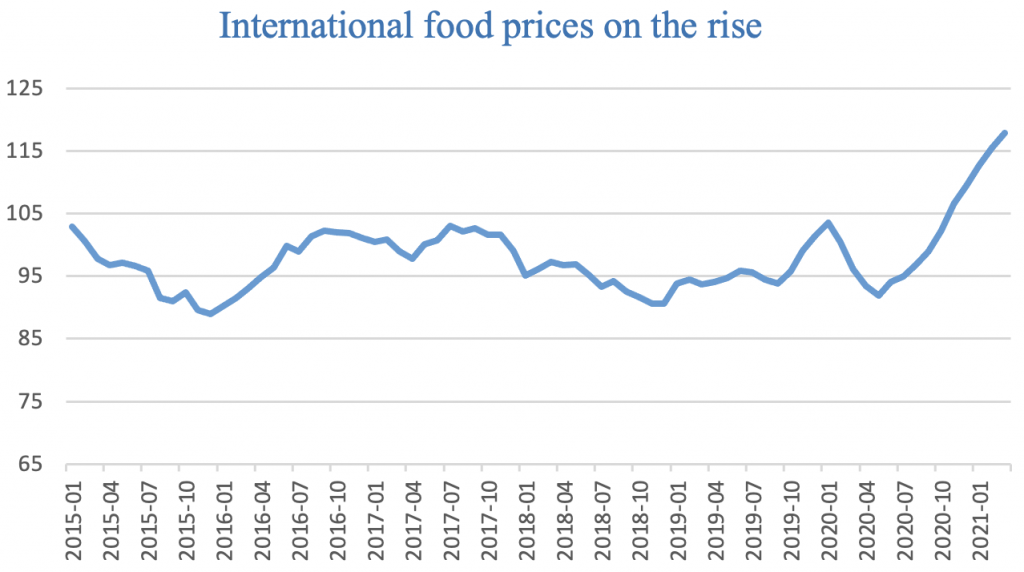

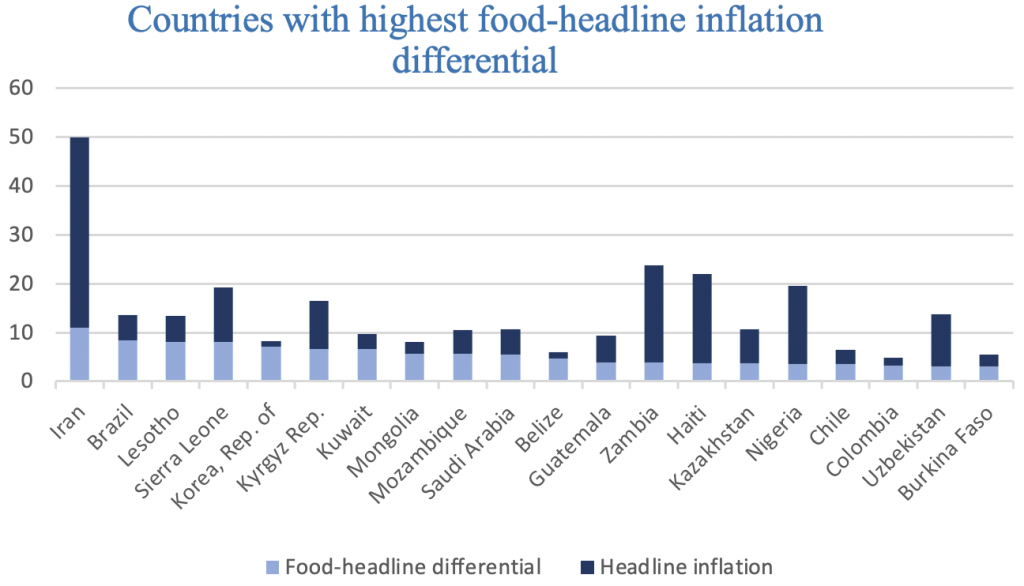

Global food prices have surged during the pandemic, rising by 25% between May 2020 and April 2021, the longest rally in more than a decade (FAO, Figure 1). Additionally, food supply chains jammed domestically from logistical hiccups and labour shortages have put a wedge between producers and consumer food prices, raising the latter (Figure 1, bottom chart).

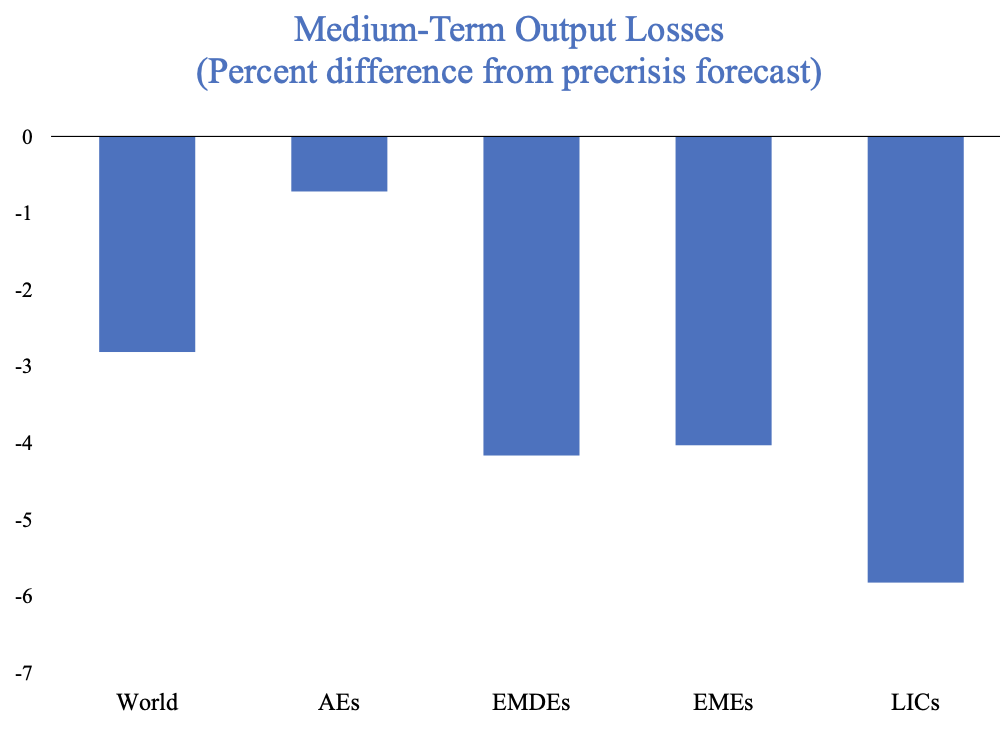

At the same time, lockdowns and other measures to contain the pandemic have led to a dramatic fall in incomes and a revision of medium-term growth forecasts, especially for low-income countries (Figure 2).

Figure 1 The impact of the pandemic on income and food prices

Figure 2 Output changes by group

Source: IMF staff calculations.

This cocktail of factors risks erasing several years of progress in reducing undernourishment globally. To help shed light on this issue, we study the links between food security, income growth, and food prices over the economic cycle. We find that GDP growth, and to a lesser extent food inflation, are prominent macroeconomic determinants of food security in emerging market and developing economies. Hence, in absence of policy actions, the number of undernourished might increase by around 60 million globally, leading to one of the most dramatic collateral damages of the current pandemic (IMF 2021).

What Is Food (In)security?

Food security is a multifaced concept. It is commonly defined as people having continuous physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life (Committee for World Food Security 2012). In absence of that, food insecurity arises. In practice, there are different ways of measuring food insecurity depending also on its degrees of severity, from worries about inadequate food quality to insufficient quantity.

Our study focuses on the prevalence of undernourishment, which measures the share of the population whose habitual food consumption lies below the minimum dietary energy requirement.1 From 2000 to 2019 the share of the global population that was undernourished declined substantially from 13.2% to 8.9%, respectively. The fast decline observed in the first decade of the century, however, started faltering in 2015. Before the pandemic struck, it is estimated that there were still more than 680 million people suffering from undernourishment (i.e. more than the entire population of North America).

Even though our study is focused on undernutrition, we try to capture other measurable aspects of food adequacy by looking at two diet composition variables: the share of dietary energy from cereals, roots, and tubers, and the average protein supply.2 As income per capita rises, diets shift from cereals to proteins (especially animal proteins). A change in diet forced by economic factors is often perceived as a descent into poverty as it is the first line of defence against rising food insecurity – a major factor behind social unrest.

Is food (In)security Macro Relevant?

Food (in)security may have significant repercussions on economic development. Undernourishment, especially if experienced in childhood, can have negative effects on physical and cognitive development. By limiting educational attainment and lifelong earning potential, it perpetuates inequality by keeping people in a poverty trap (Atinmo et al. 2009). At the aggregate level, if the phenomenon is widespread across the population, it can reduce a country’s human capital accumulation and, thus, its economic growth potential (Fogel 2004).

Indeed, the importance of food security has been formally recognised by the international community, which captured it in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 2 (aka Zero Hunger). SDG2 sets 2030 as the target for eliminating undernourishment – i.e. reducing the number of undernourished by more than 60 million per year, arguably a daunting task even without factoring in the pandemic.

Finally, history has shown repeatedly that rising food prices – and the resulting increased perception of food insecurity – can help trigger social unrest and toppled incumbent governments.3 When social unrest escalates into an armed conflict, like a civil war, poverty and hunger are further exacerbated.

What Are the Macro Determinants of Food (In)security?

Food security has two macroeconomic determinants related to the supply of food (i.e. availability) and households’ demand for food (i.e. access). The former depends on the abundance of per capita food supplies from domestic production, stocks, and imports of food. A true lack of food that would force a benevolent ‘social planner’ to ration is rarely a concern. History has shown that food is almost always available to those with buying power (Wiggins et al. 2009) – Amartya Sen observed that even in the severe Bengal famine of 1943, food was available (Tweeten 1999). We thus focus on changes in domestic food-price inflation to capture food supply shocks.4 Food access, on the other hand, relates to affordability that, for given food prices, depends on the interplay between per-capita real income and the shape of the national income distribution (i.e. inequality).

Four main candidate factors have, thus, been selected to explain changes in the prevalence of undernourishment and diet composition (Timmer 2000):

1) real GDP per capita growth (to capture household income);

2) food price inflation (to capture food supply shocks and external factors);

3) social transfers (government policies aimed at protecting the vulnerable segments of the population that act as countercyclical stabilisers); and

4) initial conditions.

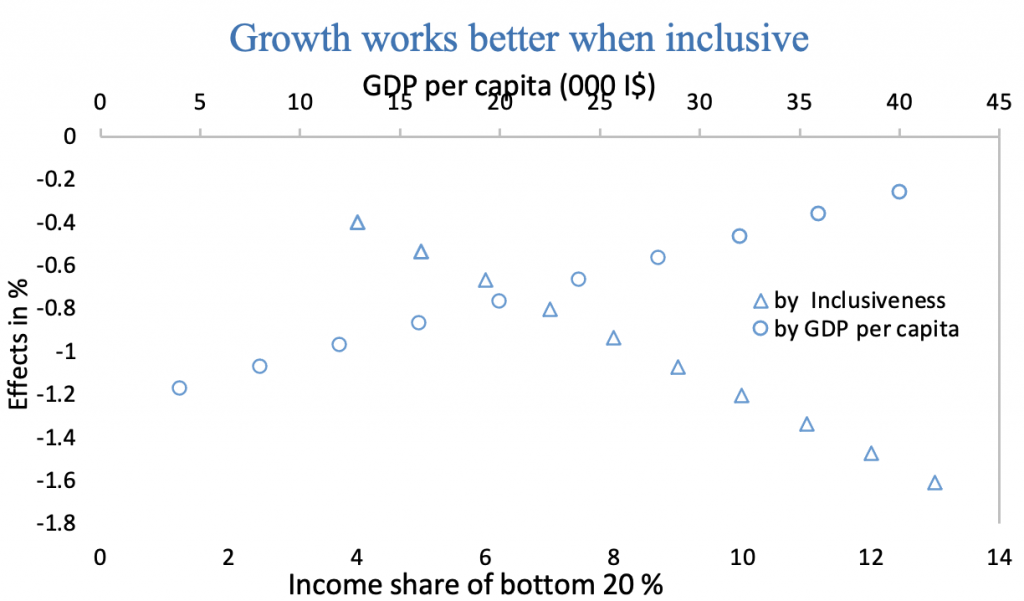

We also investigate how the effect of real income growth varies along structural characteristics of the economy, such as the stage of economic development, and measures of inclusiveness, given by the income share of the bottom 20%.

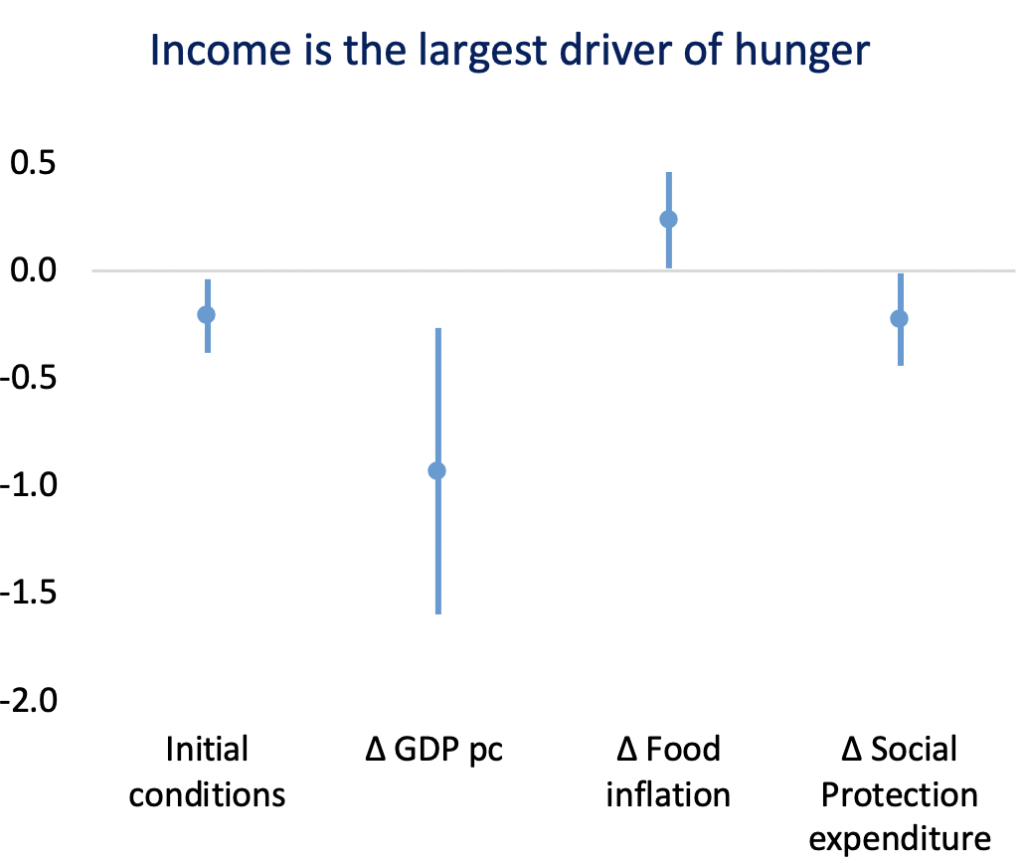

Our annual data cover 143 countries from 2001 to 2018. Higher income tends to induce both a stark reduction in undernourishment and substitution away from cereals while increasing protein consumption (Figure 3). These insights from the descriptive evidence are confirmed in the econometric analysis. Our results suggest that economic growth is by far the largest driver of global undernourishment (Figure 4, top panel). A one-percentage-point increase in economic growth leads to an approximately 1% reduction in the share of undernourished in both the random and fixed-effects instrumental variables regressions.5

Figure 3 Undernourishment, income, and diets

Figure 4 Macro determinants of undernourishment

Note: In the top graph, vertical lines show 95% confidence intervals. In the bottom graph, the lower x-axis represents inclusiveness (income share of the bottom 20%). The upper x-axis shows GDP per capita (thousands of international dollars).

In our study, the elasticity of undernourishment to inflation is smaller than to GDP growth since, for a typical change in food inflation, the share of undernourished increases by about 0.24%. Social transfers, being in part directly targeted to the share of the population most vulnerable to food insecurity, have a significant direct impact in curbing undernourishment. A typical change in social protection expenditure has the same strength as food inflation, leading to a 0.22% reduction in undernourishment. Finally, we find that countries that start with higher levels of undernourishment at the beginning of our observation period exhibit a higher reduction rate, but the catching-up is slow in absence of other improvements. Thus, overall, there is little evidence of cross-country convergence.

Results of the heterogeneity analysis show that economic growth plays an important role in reducing hunger at the early stages of development and becomes less effective as countries grow richer (Figure 4, right panel). The higher income elasticity of hunger in middle- and low-income countries relates to the bigger share of the population that is closer to the undernourishment threshold and that shifts above or below that threshold as incomes fluctuate. Growth is more effective in reducing hunger in countries with more inclusive economic systems (proxied by the size of the bottom 20% share of national income). In other words, higher inequality reduces the elasticity of undernourishment to GDP growth.

Diet composition also matters for food security. Before descending into undernourishment when incomes decline, households change their diet by moving to cheaper staple foods and cutting (animal) protein consumption. This margin of adjustment is quantitatively relevant. A negative 1 percent GDP shock tends to increase cereal consumption (by 0.06%) and decrease protein consumption (by 0.55%), tilting the diet towards cereals.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic and its scars risk jeopardising the process of bringing the number of undernourished people to zero by 2030. In fact, econometric analysis suggests that real income changes are by far the largest driver of hunger, followed by food prices and social protection schemes. Absent policy interventions, the 2020 decline in income and increase in food prices would lead, respectively, to 57 million and 3 million increases in the number of hungry people, hitting especially low-income countries. The economic fallout from the pandemic risks setting us back a full decade on eliminating undernourishment.

Social protection, by complementing the income of the most vulnerable households, helps keep inequality under check. It is a valuable shield against income and food price shocks, as it reduces the elasticity of undernourishment to income shocks for a given level of economic development. Governments should thus strengthen safety nets for the most vulnerable and mitigate the risk of food-price spikes by guaranteeing the smooth functioning of food supply chains.

See original post for references

The web-formatting of this article needs to be corrected. Most of the body copy is appearing in the headline font and size.

Fixed the formatting. Thanks for the heads up!

Red State Pols think unemployment supports are supporting laziness on the part of the slave class. Biden shrugs and says, “Maybe you’re right.”

So this is how food (in)security is supported. I find it curious that human needs are always quantified in terms of their effect on GDP. As if that is going to get anyone off the dime to recognize that well-nourished people are more productive. No, people have to be starved into working for a sub-standard of living on all counts.

From each according to their need; to each according to their power: the basic principle of liberalism-capitalism. Well-nourished people are more productive; ill-nourished people are more submissive.

Since the owning class has captured all of the productivity gains of the last fourty years and has no idea what to do with all their winnings, they are no longer concerned with actual productivity.

They pay it lip service, but with free money for the monied from the Fed, actual investment necessary to improve productivty is way riskier than speculation.

All they are concerned about now is controlling all those people they’ve ejected from the system, they call them “useless eaters” to valorize their thefts and displace blame from themselves.

I haven’t read the referenced paper but I would question this. Food, surely, is primarily available to those producing it. Those not producing it must obtain it from those who are either by buying it or taking it by force – and where food is short those producing it will want to retain at least sufficient for their own needs, and you can’t eat gold or silver so ‘buying power’ is irrelevant. Hence in times of shortage non-producers must resort to violence to take it, thus risking starving the producers and future production.

Too ‘historically’ there have been far more food producers as against ‘parasites’ feeding off them than is the case today, allowing for a greater ‘cushion’. The parasites could absorb some of the produce for their own needs, either by buying it or taking it by force, without fatally weakening the ‘host’, ie the body of producers. If everyone today was given an equal right to a share of food produced, rather than the producers’ surplus being allocated by wealth, would there be enough to go around?

People who think they may be in a position to grow at least a little food for themselves may start to do so.

Or at least look into it.

Meanwhile, as to the poor people, perhaps the Democratic Socialists of America can diversify from Tail Light Clinics into subsistence gardening clinics, making-sprouts-from-grains, beans and seeds clinics, etc.

This is not necessarily true in practice. To give one example, the potato famine in Ireland was only fatal to so much of the population because the grain (primarily barley) being produced in Ireland continued to be exported, and a majority of the grain which was not exported (or was imported) was used to feed livestock instead of people. Result: 1 million dead, 1 million emigrated.

The same could be seen in the early days of of vaccine production in Europe, where vaccines produced in Belgium and the Netherlands were exported to those with more favourable contract terms. Never underestimate the power of contracts in a free market!

Food insecurity. Euphemism for poverty and hunger, and starvation. Sounds better, doesn’t it?

Annoys the heck out of me.

Just as climate change sounds better than global heating.

Climate change is much more accurate in describing climate chaos than food insecurity is describing hunger/starvation. I agree, Sue inSocal.

The climate chaos is driven by man made global heating. Frank Luntz invented the word “climate change” in order to drive the word ” global warming” out of use, because “climate change” sounded nicer and the fossil fuel hasbarists could argue that “climate always did change and always will”.

So I like “global heating” better.

Climate dechaos decay is nice, too.

Arab spring 2011, bread shortage and rice market disruptions. 2021 Protein wheats headed for a very short crop in US and Canada, with stress in Black Sea too. Rice heading for a big crop this summer so political disruption from high priced, hard to get bread not likely ala 2011, but shipping logistics at ports likely to cause supply disruption. Corn and beans in Brazil and US all under weather and subsoil moisture stress with Chinese stockpiling due to building out hog CAFO’s to substitute for banned feeding of table scarps from individuals and restaurants to combat ASF.

Seventh century B.C.E., one Kuan Chung, chief minister of Ch’i, wrote, “Only when clothing and food are adequate can men know glory and shame.” In other words, empty stomachs override the constraints of the state.