By Martha J. Bailey, Professor, Department of Economics, University of California-Los Angeles, Shuqiao Sun, Economist, World Bank, and Brenden Timpe, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Nebraska. Originally published at VoxEU.

Preschool attendance in the US is largely funded by parents, which means that the children of more affluent and educated parents are more likely to attend. This column looks at the impact of Head Start, a large-scale preschool programme that serves roughly 1 million children annually in the US. The results show that children age-eligible for Head Start went on to achieve substantially higher levels of education. Head Start also led to improvements in adult economic self-sufficiency. Overall, the findings suggest that a large-scale preschool programme – even one with less per-child expenditures than model preschools – can deliver long-run benefits to students.

Access to preschool is unequal in the United States. Unlike the near-universal public programmes in many OECD countries, preschool attendance in the US is largely funded by parents. This means that the children of more affluent and educated parents are more likely to attend. The 4-year-old children of mothers with college degrees are 35% more likely to attend preschool than the children of high-school dropouts. This inequality in preschool attendance means that children of less educated and less affluent parents start kindergarten and first grade already behind in terms of social and academic skills.

Whether universal, public preschool will help close these gaps is a matter of debate. Although small-scale, high-quality model preschools have delivered impressive results (Barnett and Massie 2007, Anderson 2008, Heckman et al. 2010, Currie 2001, Duncan and Magnuson 2013), large-scale public programmes spend less per child and may do correspondingly less to close the gap in preschool access than model programs.

Our research adds evidence to this debate drawing on the early years of Head Start (Bailey et al. 2020). Begun in 1965, Head Start is a large-scale preschool programme that serves roughly 1 million children annually in the US. In its early years, Head Start cost about 25% of the amount per child as model Perry Preschool and Abecederian projects but achieved widespread coverage, operating in communities where over 80% of US children lived by 1980. Similar to more recent proposals to expand universal preschool, Head Start’s effectiveness has long been contested, fuelled in large part by experiments that found the programme improved test scores in the short run but that they “faded out” in subsequent years (Puma et al. 2010).

Harnessing large-scale, restricted data on children’s long-run educational and employment outcomes from the 2000 Census and the 2001-2018 American Community Surveys and Social Security records, we examine how access to Head Start shaped children’s lives. To isolate the causal effect of the Head Start programme itself, our analysis compares children who were age-eligible for Head Start (ages 3-5) to children born in the same county who were age 6, and therefore too old to participate before first grade when the program began.

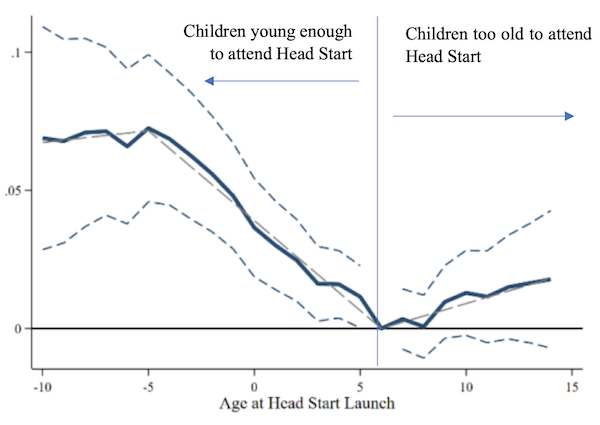

Our results show that children age-eligible for Head Start went on to achieve substantially higher levels of education – even though the programme was underfunded compared to model preschool programmes. Figure 1 shows the effect of Head Start on completed years of schooling for children relative to their age when their local Head Start launched. Compared to children age 6 who were entering first grade when Head Start began, the slightly younger cohorts who were more likely to attend Head Start attained significantly more education in the long run. The effect increases as we move to the left in the figure, which is consistent with new preschool programs taking some time to ramp up to full capacity. In contrast, there is no change in the outcomes of children born in the same county who were ages 7 to 14 – too old to be eligible to attend Head Start.

Figure 1 Years of completed schooling by a cohort’s age when Head Start launched

Focusing on children who attended Head Start when it was fully implemented, we find that children who attended the programme achieved 0.65 more years of education relative to children who were too old to attend. Head Start also led to a 2.7% increase in high school completion, an 8.5% increase in college attendance, and a 39% increase in the share earning a 4-year college degree. These effects are present both for boys and girls, and for white and non-white students.

We also find that Head Start led to improvements in adult economic self-sufficiency. An index summarising improvements in multiple dimensions shows fully treated children exhibit an improvement that is equivalent to 9% of a standard deviation – effects driven by an increase in employment, hours worked, and weeks worked. Boys participating in Head Start were 42% less likely to receive public assistance, such as disability insurance payments, as adults, while girls were 32% less likely to live in poverty in adulthood.

Unfortunately, less information exists in the historical record about the mechanisms for these effects. Heterogeneity analyses allow some tentative conclusions. One potentially telling finding is that the education effects of Head Start are largest in places where children were more likely to have access to Medicaid, the United States’ public health insurance programme for the poor. This evidence suggests that Head Start’s health screenings were an important contributor to improved outcomes, because Medicaid allowed poor children to get glasses or hearing aids, enabling them to learn. It also helped parents get treatable non-emergent health problems addressed, such as antibiotics to prevent ear infections which could lead to long-term hearing loss. Another notable finding is that the effects are smaller in counties that were early adopters of the Food Stamps programme, suggesting that Head Start may have substituted Food Stamps in providing nutritious meals that helped children succeed in school.

A final analysis quantifies both the private and public, internal rates of return to dollars spent on Head Start in the 1960s and 1970s. This exercise suggests a private internal rate of return to Head Start of 13.7 percent, which is similar for both men and women. Using only savings on public assistance expenditures and increases in tax revenue due to higher wage earnings to calculate the programme’s social returns, we find that the public internal rate of return of putting one child through Head Start ranges from 5.4% to 9.1%. While the range of these returns reflects different assumptions about who the marginal beneficiary is, the bottom line is that America’s first scaled-up, public preschool programme generated sizeable returns over the lifetimes of its early participants.

While the population of American pre-schoolers today is undoubtedly quite different from the children of the 1960s and 1970s, these findings suggest that a large-scale preschool programme – even one with less per-child expenditures than model preschools – can deliver long-run benefits to their students. This may be an important piece of the puzzle as policymakers decide whether and how to expand access to preschool today.

I am always curious about how to demonstrate the utility of programs intended for long range benefits without a lot of hand waving. This is interesting but not without limitations. Since the researchers are using different generations as comparison, the intervention effect is confounded by time and the cultural changes that go with it. I do not see how they controlled for that.

Nevertheless, I feel kids do benefit and am glad for the program. It’s just hard to demo the benefit of long range public programs to critics with all sorts of short-term arguments why it is too expensive. I wish I had a sol’n to that.

In order to promote the social, intellectual and emotional development of pre-school children, they must be taught by qualified staff. From anecdotal evidence I have received the distinct impression that Head Start teachers are underpaid and consequently underqualified. Wages of such teachers must be substantially raised in order to attract better qualified staff.

Sorry. I actually looked at the early Head Start data working as a temp-contractor for the fedeal government on two occasions in the 1970s. I (and all of us) were very hopeful and impressed by the early jump in the Head Start kids’ achivement. We helped keep the program going into the Nixon years based on the early studies. Unfortunately the effect slowly vanished with age so that by age 12 there was no noticible difference between Head Start kids and those who didn’t attend. These were direct “paired kids” studies, funded by the Department of Education and peer reviewed. You can find them by looking in ERIC (the social science research index).

The present authors said the following: “To isolate the causal effect of the Head Start programme itself, our analysis compares children who were age-eligible for Head Start (ages 3-5) to children born in the same county who were age 6, and therefore too old to participate before first grade when the program began. (new para) Our results show that children age-eligible for Head Start went on to achieve substantially higher levels of education – even though the programme was underfunded compared to model preschool programmes.”

They are not comparing Head Start student to non-students; they are comparing poor kids born before 1959 to those born after. There were many changes from 1965-70s that lead to the “children age-eligible for Head Start went on to achieve substantially higher levels of education” result. The authors are professionals and know statistics; this article appears to me to be a polemic that misuses statistics and is misleading.

It is still unclear to me if a Head Start-style program can lead to long-term improvements if it is prolonged and properly managed… but the Head Start program of 1965-70s didn’t do it.