By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

I stumbled across a reference to the Mindat site (“Mineral Database”) in Hacker News, and as a fan of citizen science, I thought I should go look at it, and see if there was anything post-worthy. There was, at least I think so. Some NC readers will surely find Mindat useful, since it’s a really good site on minerals and where to find them. However, Mindat also shows how platforms like Google and Wikipedia are playing a highly dubious role in “organiz[ing] the world’s information,” as Google puts it. First, I’ll look at Mindat’s history and site architecture. Then I’ll look at a use case — geodes in Iowa — and compare Mindat to Wikipedia as a “widely accessible and free encyclopedia,” as WikiPedia puts it. Spoiler alert: Mindat wins. Finally, I’ll look at Mindat and Google (and Google and citizen science generally).

Here is a page on Mindat’s history, as told by its founder, Jolyon Ralph, at least as far as 2010. Mindat began as a personal computer database project Ralph wrote from scratch, starting on Christmas Day 1993, using C++ on his 386 laptop; it ran as a DOS application. Ralph than rewrote it for Windows 95. Then he had the key insight:

But the big problem was still that all data had to be entered by me, by hand, the other users of the software could not contribute. For several years I looked at different solutions to this problem, but it was only in 2000 that I came up with the plan to convert it into a website and program that so that others could edit. This was, by the way, a year before Wikipedia was launched.

Here is a random example of the resulting online community in action. From 2010:

I have long noted that the Greek roots of some mineral names are wrongly spelled or translated in the “name origin” field in the database. I will start trying to make some corrections, although this is probably going to be a rather long thread.

Here are a few:

Glaucocerinite: From the Greek γλαυκός <ΝΟΤ "γλανκός"> for “sky-blue” and κήρινος for “wax-like,” in allusion to its colour and appearance.

Also I think there are some better Glaucocerinite photos than the one currently used as a head-photo. I would suggest http://www.mindat.org/photo-293676.html that shows a very high-quality specimen with top colour.

The same applies to the name of Natroglaucocerinite….

Great stuff! (And in my mind, what “the Internet” should be all about. If you want to become an influencer, this is the way to do it.) There is an extensive manual to make sure contributors adhere to data entry standards and don’t go off the rails. in addition, the work is reviewed: “This information is entered by an army of volunteers worldwide and then verified by our team of experts.”

Mindat’s site architecture is complex. It doesn’t look like it should be, but it is. It bundles together functions that are generally standalone applications, all centered on minerals:

Mindat.org is the world’s leading authority on minerals and their localities, deposits, and mines worldwide.

Mindat.org’s mission is to advance the world’s understanding of minerals.

Mindat.org has been collecting, organising, and sharing mineral information since October 2000. It is now an essential resource used daily throughout education, academia, and industry.

Mindat is at once a message board, an image host, and a blogging platform, besides being an encyclopedia.

Mindat is a board, with threaded messages. (Here is a thread on “What’s your least favourite mineral name, and why?“)

Mindat is a photo host, like Flickr or Photobucket. (Here is one user’s photo page: “Museu de Ciência e Técnica – Escola de Minas – UFOP’s Photo Gallery.”)

Mindat is a blogging platform, like Blogger or WordPress. (Here is a post on “Micromineralogy in a day hospital,” which is worth a read if you have a minute or two.)

But Mindat would be nothing if it were not also an encyclopedia, so let’s turn to that function, and compare it to Wikipedia, also an encyclopedia. I happen to know that the geode is Iowa’s official state rock. So first I will compare the entries for “geode” in both encyclopedias., and then “Iowa.”

Here is Wikipedia’s definition of geode:

A geode (/ˈdʒiː.oʊd/; derived from the Greek “γεώδης”, meaning “Earth-like”) is a geological secondary formation within sedimentary and volcanic rocks. Geodes are hollow, vaguely spherical rocks, in which masses of mineral matter (which may include crystals) are secluded. The crystals are formed by the filling of vesicles in volcanic and sub-volcanic rocks by minerals deposited from hydrothermal fluids; or by the dissolution of syn-genetic concretions and partial filling by the same, or other, minerals precipitated from water, groundwater or hydrothermal fluids.

And here is Mindat’s:

Geodes (Greek γεώδης – ge-ōdēs, “earthlike”) are commonly independent spherical masses of resistant mineral matter that are usually hollow. The extreme filling of a geode so that it is “solid” is also common. Some people refer to completely in-filled geodes as nodules, but the two names are not always consistently used. Geodes differ from “nodules” in that a nodule is a solid mass of mineral matter, but some nodules may have a tiny void space in their interiors and the distinction between a geode and a nodule may be barely discernible if the cavity is miniscule. Geodes differ from vugs in that geodes can be separated free from any matrix, because the walls of geodes are strong enough to maintain the integrity of their initial shapes. Geodes differ from vugs in possessing an outer mineral layer which is more resistant to weathering than the host rock.

If I had a rock in my hand and wondered whether it was a geode, I think Mindat’s definition would be far more useful.

And now Iowa (and this is really a set-up for Mindat). From Wikipedia:

Iowa (/ˈaɪoʊwə/ (About this soundlisten))[7][8][9] is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the east and southeast, Missouri to the south, Nebraska to the west, South Dakota to the northwest, and Minnesota to the north.

A generic entry, in other words. We do learn that Iowa has an “Inanimate insignia, a rock: the geode.” And here is Mindat:

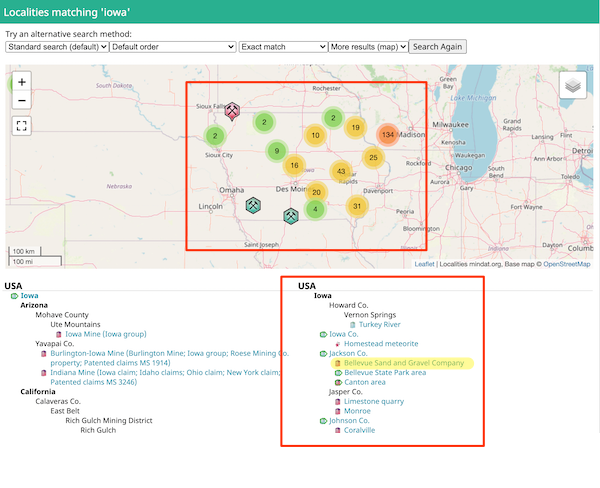

With Mindat, search yields me a map of all the known locations in Iowa where geodes can be found, down to the granularity of individual, named sites. If I am in Jackson County, I can go to the Bellevue Sand and Gravel Company. It even has its own page! (There is also a more conventional page for the State of Iowa, that includes the same map, but also has a lot more geological information.)

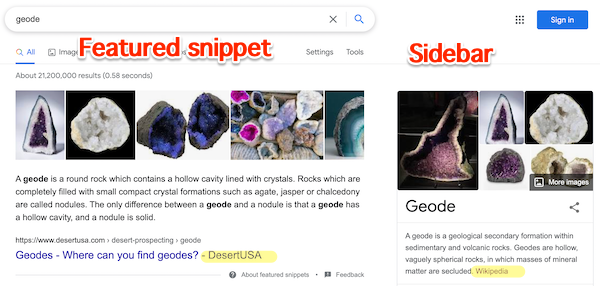

And now we come to the platforms. Here are the results for a Google search on “geode”:

The (crapifed) Google search page has a “Featured Snippet” from DesertUSA, and a Sidebar item from Wikipedia. Let’s look at each in turn.

In the Featured Snippet, there seems to be no obvious rationale for choosing DesertUSA as a source. As its name implies, and it’s About page states, “DesertUSA has information on national parks, state parks, BLM land, and the Colorado River and its lakes.” It has no particular focus on geodes. Their page on geodes contains inanitities like “Geodes are a variable phenomenon, which means that they may be created in various different ways.” If you compare their snippet on geodes to Mindat’s defintion above, you will see that they are wrong that geodes are always hollow, wrong that geodes are always lined with crystals, wrong and wrong on the definition of nodule. DesertUSA do, however, does sell crystals in their shop. Perhaps that’s why Google featured them.

In the sidebar, there is one source: Wikipedia. I hope I have persuaded you, readers, that Mindat also deserves to be there, if not replace Wikpedia’s entry entirely. Why is it not?

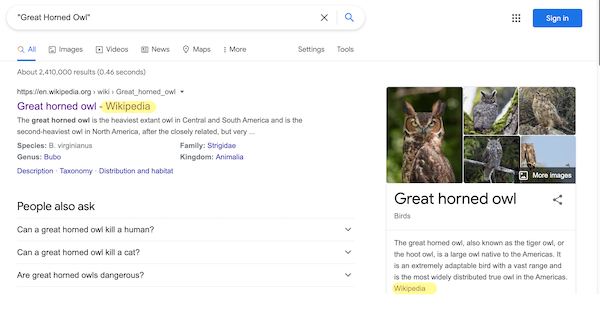

I could believe it was coincidence that an encyclopedic, community-driven site like Mindat did not appear in Google’s sidebar, were it not for an apparent pattern and practice of suppressing such sites entirely. Readers will be familiar with the Macaulay Library from Water Cooler; it’s my source for the Bird Song of the Day. So let’s Google “horned owl” and see what we get:

How odd. Wikipedia in the Featured Snippet; Wikipedia in the sidebar. No Macaulay Library to be seen. Can anyone seriously argue that Wikipedia is a better source for information on Great Horned Owls than the Macauley Library?

Mindat needs donations to survive. By not throwing eyeballs and clicks toward the better content Mindat provides Google, the giant monopoly, is actively harming that community (in addition to making it harder to produce the world’s information). And Wikipedia, the beneficiary of Google’s malevolent algorithms and policies, is no better. Michael Olenick wrote at NC:

Ignoring Wikipedia, which is every bit as much a monopoly and a monopolist as the rest, is a dire mistake. There is nothing positive about sucking away users from high-quality content published by individuals, small blogs, or focused wikis. They’re not providing some type of public service by providing free content for Google to monetize without worries about being sued for copyright violations (and, surprise, Google funds Wikipedia).

Perhaps, somehow, this post will get onto Lina Kahn’s desk. Following that unlikely event, perhaps an even more unlikely event will follow: The Biden administration and Congress will allow her to do something about it.

I forgot. Geodes are really beautiful. From Mindat:

Yikes! Beautiful, but looks like a Klingon lamprey. :)

” What the Internet should be all about” is so foreign to a lot of people today that if they saw it, they would try to destroy it.

Better to find a way to create ” an” Internet for people who want a good Internet and call it the Shinolanet.

And let everybody else have their Shitternet. Shinolafluencers who want a Shinolanet could hopefully focus on creating that for people who want it, and not try to compete against the Shitfluencers who like the Shitternet as it is and as they want to keep it.

Wouldn’t this be the difference between an academic database and an encyclopedia entry? I’m not sure why they would be in the same class.

Same reason I’d look at a Haynes manual instead of the wiki entry for my truck

I think there is a problem with people who aren’t a specialist in a topic and so find it difficult to judge the quality of the information they find. So for example, if you are a geologist, or a geological engineer, you will know all the main databases and how to interrogate them. But if, for example, you are an ecologist, or a structures engineer, who might need to find something out on geology a few times a year, you can easily go astray. I find the biggest errors are always made by people who know just enough about a subject to get out of their depth very quickly.

As Cocomaan said before, a specialised source of information would usually be better than a general one.

The sidebar contains an excerpt from Wiki or google’s own content whereas an automated algorithm determines what appears in the featured snippet. I’m not sure the featured snippet should exist at all as usually it’s not more helpful than the first search result.

Would you really want Google to decide what is the best source of information for a given topic that deserves being in a sidebar? I think the results might disappoint you.

Great post Lambert.

I’ve used minedat in the past, as I am a bit of a rockhound.

If you ever get a chance to go to the public sunstone collecton area of Oregon, it’s a fantastic trip. The crystals just sit above the sand, and you just pluck them off the ground.

Very few visitors, and a black night sky like you wouldn’t believe!

Just a general point on getting information on geology (and most of the natural sciences) – one problem is that so much online information is on various forms of GIS or other maps, so standard search isn’t good at finding it. It also doesn’t help that a lot of information is layered for access (some national geographic databases charge fees for access to the most detailed layers). This can make doing searches for locally based information a real pain if you are not very familiar with the online sources.

I don’t know the situation in the US, but its also the case that a surprising amount of information is not put online in Europe. A friend was doing some local area research and found that a lot of information obtained as part of various permit permissions (ecology surveys, groundwater information surveys, archaeology, etc), was simply sent to the town/county library and stored away on files – or sometimes scanned into pdfs. It only turned up by doing research the old fashioned way, going to a library and asking to see the old documents. Also, a lot of information put on public display as part of Environmental Assessments of one form or another are put in various non html formats so don’t come up well in searches (I suspect this is deliberate sometimes as the authors want to limit access as much as they can get away with legally). I’ve come across people (especially younger researchers) who are completely unaware of this, they think if information can’t be found on google, it doesn’t exist.

You inadvertently described the difference between Minnesota and Wisconsin with regards to geological and geophysical information.

Minnesota: centralized, publicly available, served up both as library entries and GIS. There’s still some records that are hard to find, sometimes by design (sewer records, mining claims, etc.), but what’s out there is abundant, immediately useful, and gradually increasing in quantity and quality.

Wisconsin: decentralized, with just enough geological information publically available to be frustrating. Some areas have a trove of detailed information (e.g. Little Plover River aquifer tests)., but other areas the “Roadside Geology of Wisconsin” book becomes a critical tool, as it is often the only information available for a particular location.

Practical difference: my billable rates as a geologist are the same in both states (I’m licensed as a PG in both), but I add several hours or more to Wisconsin protects in research time knowing that finding useful background information is going to be challenging.

One reason for this difference: Minnesota has the Legacy Amendment which provides funding for arts and sciences, which includes scanning geological maps and creating digital access for these records. Wisconsin has no such source of funds.

Cool post, Lambert, thank you! I love minerals and Mindat looks like a great resource, I’ll check it out!

The fact that Mindat has a strong focus on only one topic means that it can evolve an optimized structure for accreting subsystems (photo collection, blogging, etc.) that matches how people want to use the site. Wikipedia, on this front, has the “if a program tries to do too much, it becomes unuseable” problem. They wisely focused on articles and media servers.

If you want to make something like Mindat for, say, archeological food science (ancient recipes, ancient beers), it would also be possible to make something as optimized for that topic. The pieces probably would not fit together like they do in Mindat.

If you don’t like Wikipedia (understandable), consider using Infogalactic. It has a higher growth rate and largely lacks the edit wars.