By Alexander Ahammer, Assistant Professor, Johannes Kepler University Linzl, Dominik Grübl, PhD candidate in Economics, Johannes Kepler University, and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer, Professor at Labour Economics at the University of Linz and at the Institute for Advanced Studies, Vienna and CEPR Research Fellow. Originally published at VoxEU.

COVID-19 and the policies enacted to tackle virus transmission have led to a wave of unemployment in Europe and the US. This column uses data from Austria to examine the impact of downsizing by a firm on the health of people who remain at the firm. It finds a significant increase in drug prescriptions and hospitalisations following mass layoffs, driven primarily by mental and cardiovascular conditions. The authors argue that stress due to fear of job loss, rather than increased workloads, is the more likely explanation.

Downsizing is a frequently used tool to stabilise firms in distress. Recently, COVID-19 and the policies enacted to tackle virus transmission have led to a wave of unemployment in Europe and the US (e.g. Baek et al. 2020). This is particularly concerning in times of a pandemic because an increase in unemployment can exacerbate problems in the already strained health sector. The health effects of job loss and labour market shocks have been widely documented in the literature (e.g. Kuhn et al. 2009, Adda and Fawaz 2021). In a recent study (Ahammer et al. 2020), we show that downsizing also affects the health of workers who remain in the firm. These effects can occur when staff reductions lead to psychological stress in the workforce. This can be the case, in particular, if the remaining workers fear for their own jobs or are pushed into new tasks and responsibilities.

To investigate the health effects of downsizing, we look at workers who remained in firms that underwent mass layoffs between 1998 and 2014 in Upper Austria. Since surviving a mass layoff is not random, we construct a control group of workers from other firms who themselves survive a mass layoff, but at a later point in time. These workers should have similar unobservable characteristics compared to our ‘treatment’ group and differ only in the timing of the mass layoff they are exposed to.

Effects on Workers’ Health

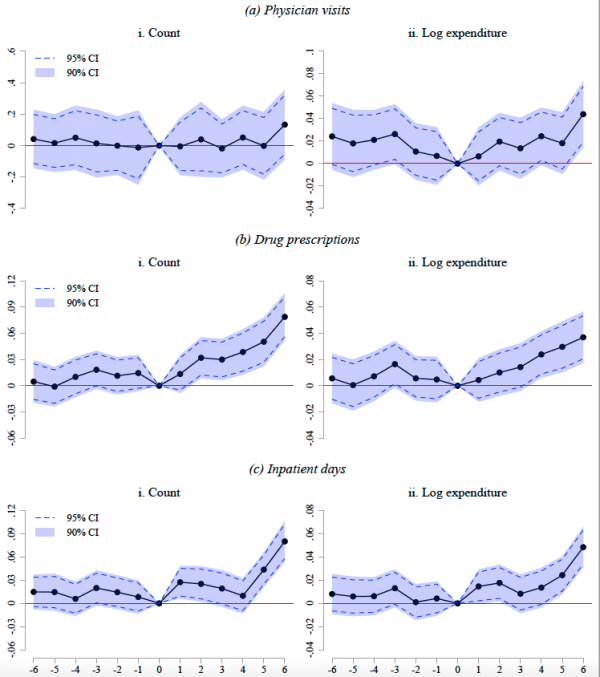

Our central results, based on dynamic difference-in-differences estimates, suggest a significant increase in drug prescriptions and hospitalisations following mass layoffs among workers who remain with the firm. These results are shown in Figure 1. In each graph, the dots indicate the estimated effect of mass layoff in a certain quarter, relative to the base quarter (the quarter of the mass layoff). The blue area is the 95% confidence interval and the dashed line is the 90% confidence interval of the estimate. These effects are persistent and, in fact, become stronger over time. This is not surprising, given that stress arguably takes some time to take its full toll on the body. As recent medical studies have shown, even minor stressful events can lead to serious health problems that linger for ten years or longer (e.g., Korkeila et al. 2010).

Figure 1 Effects of mass layoffs on workers who remain at the firm

Notes: These graphs show dynamic difference-in-differences estimates for the effect of a mass layoff on health outcomes of workers who remain with the firm, each over a period of 6 quarters before to 6 quarters after the mass layoff. The 95% confidence interval is indicated by the blue area, the 90% confidence interval is shown as a dashed line. In all regressions, we control for worker age and tenure.

These effects appear to be driven primarily by mental and cardiovascular conditions, both of which have been linked to work stress in the occupational health literature. For example, workers are 20% more likely to seek psychotherapy following mass layoffs. Prescriptions for antidepressants, however, increase later and to a lesser extent, which is also true for musculoskeletal conditions. For cardiovascular drugs such as beta blockers or anti-cholesterol drugs we see an immediate increase, but not for strokes or heart attacks. In general, it seems that workers with pre-existing conditions tend to be more affected by downsizing. We find no evidence for effects on alcohol or drug abuse.

Fear Of Own Job Loss Or Higher Workload?

How can these health effects be explained? Are workers afraid of losing their own jobs? Or does stress arise because downsizing leads to restructuring and thus to a greater workload? We consider the latter to be less likely, because our estimated health effects are somewhat stronger for smaller layoffs. When fewer workers are laid off, it is less likely that a systematic redistribution of work tasks will follow. Furthermore, mass layoffs have little effect on wages of the remaining workers in our sample. If they were given more responsibilities following mass layoffs, we would expect salary jumps sooner or later, but this is not consistent with our results.

Stress due to fear of job loss, on the other hand, is the more likely explanation. This is supported by the fact that more vulnerable workers, such as older low-wage workers, are more affected. Furthermore, the health effect occurs only in communities with above-average unemployment rates and is larger for workers whose spouses earn below-average wages. These groups of people each face the greatest costs of potential unemployment and therefore will also tend to be more fearful of job loss.

Downsizing Requires Management and Policy Action

Downsizing thus affects the health of workers who remain at the firm. Such externalities impose significant costs on the firm itself, as sick leaves increase substantially after mass layoffs. Evidence for such spillovers has been scarce in the literature. This has important implications for policy and management. If health effects are not offset by compensating wage increases, a specific layoff tax along the lines of Blanchard and Tirole (2008) could be useful. Such a tax would internalise the external effects of (mass) layoffs, such as costs for unemployment benefits. Likewise, measures such as targeted health counselling or prevention can be helpful in dampening health effects on workers remaining in the company.

Yikes! The authors write as if there was an efficient and ‘serious’ health care policy making apparatus in place. That doesn’t sound anything like America today.

I personally have seen “doubling up” of work responsibilities and mini layoffs in so called “normal” times. This, to the best of my knowledge, was the result of a company being bought up by venture capitalists, [also known as Vultures,] and also the slow grind of continual demands for increases in Return on Investment by the “shareholders,” and or their “representatives” in Management. Even flat ‘returns’ for a quarter would spur on middle management to “crack the whip.” In such an environment, the health of the workforce is of no importance whatsoever.

Welcome to the New World Order!

I lived through an almost five year period at a company that had major layoffs about once or (on occasion) twice a year. I’m a little surprised this analysis puts job security vs. work load as an either/or causality. For us, it was definitely both working together that wore one down and, over time, made for a remarkably depressing, pressure cooker of an experience.

More specifically, the additional work load (that increasingly bordered on and finally landed smack dab in the category of the truly absurd) generated resentment and then added to that was the constant worry that another hit was coming and you were sure (this time) to be in it, both gnawed constantly at you; at home and at work – especially if you had a family depending on you. Think about it; we sure did, there was no way one could accomplish the work load, yet mgmt., who had gone nuts, made it look like they really expected you to, and so surely they were going to put you on the hit list for the next blood bath. The two worked beautifully together to make life utterly miserable and to inspire profound cynicism.

It should be added that management, particularly but not exclusively upper management, added significantly to this (like fingernails on a black-board) with their inane, nonsensical pep-talks: “We’re going to work smarter, not harder…” Also of interest was that ground level management, the ones we worked with day to day, started to get more realistic and less patronizing with pure, utter absurdities as they began to get laid off in substantial numbers along with the rest of us.

I managed to get a job elsewhere before they went out of business (were bought up for pennies by a competitor); it felt like a cork being released from deep under water.

The worst years of my life were the result of healthcare downsizing. Our support unit (supply) was downsized from 3.5 to 1 (me). Of course some responsibilities we’re offloaded, but I still was running behind constantly and didn’t haves good nights sleep for 18 months. And yes, there were mental health issues (drunken recklessness). As soon as I have changed jobs the symptoms disappeared, but it took 18 months to do that.

“Do more with less!” With big smiles on their faces, PhDs and MDs would repeat this Inane slogan as though it we’re Newton’s Third Law.

I would be interested to know about the long-term impact as well.

If you’ve ever been downsized or otherwise lost your job through no fault of your own, that anxiety can stay with you for a long time and you wonder whether a given day will be your last even long after you’ve found a new job.

The practice of forced ranking of employee reviews or “rank-and-yank” as pioneered by Jack Welch of GE is still practiced by many large firms when it comes to employee management meaning. This was a common thing for the salaried workers at the companies that I have been with, and it basically means that it does not matter how great an employee is at their job with rank-and-yank as somebody has to be ranked at the bottom and then these people are promptly fired no matter what they did or did not do in regards to their position.

While it encouraged a lot of employee backstabbing among the salaried workers, upper management saw it as a way of keeping employees on their toes.

I got caught out in the UK’s 1980s/1990s real estate boom and bust.

I was the mug who got in just before the bust.

Property had been rising in price throughout the 1980s and I thought this just can’t go on, but it did.

I was getting older and wanted to buy my own place, but I was wary, as I thought this boom couldn’t last. The removal of dual tax relief on mortgages forced my hand. If I didn’t buy now, I would never be able to afford it.

There was one last sharp upswing before the crash.

My property was falling in price, the economy was in recession and the threat of redundancy wasn’t far away.

This went on for years.

The only consolation being there were plenty of people my age in exactly the same boat.

This seemed to be just the opportunity neoliberals needed to transition from the old ways to the new ways.

Jobs were scarce and people were worried, so they could treat employees pretty badly and get away with it.

Before this firms had been more like a family in many ways.

There was a Personnel Department that looked after the personnel.

You worked and helped to produce a profit for them and they paid you a wage that allowed you to live a reasonable life.

Jobs were full time and secure.

You had to behave pretty badly to get sacked.

After the transition.

There was a Human Resources Department that ensured the human resources were there to do whatever the company needed.

As an employee it was all about looking after number one, a firm was never going to look after you when the going got tough.

Job security disappeared.

I was working at a firm where we had wave after wave of redundancies.

Strangely nearly all the redundancies were made at the lower levels and I was looking forward to the day when I had my very own manager to ensure I used my time very productively.

As time went on, I knew my time was coming.

It was strange how so many did not really have much idea of their own worth to the company.

Very god people were overly anxious, even though they were going to be the last out of the door.

Not very good people were totally shocked they had been made redundant so early.

I knew what round of redundancies I would go on and I did.

I could have made more of an effort, but it was an awful environment to work in and I needed a push out of the door. I also got some redundancy money.

I managed to keep my head above water and eventually things improved.

If things don’t go well, you can easily get dragged under.

I remember seeing someone I used to work with on the back of a flat back lorry collecting and sorting rubbish.

He saw me, and the expression on his face said it all.

“How did it come to this?”

He didn’t work at the same level as me, and didn’t have the same opportunities; he suffered badly.

He was one of those typical people you used to get, very hard working and diligent, who had grown up in a world where this was the way through life.

You did your bit for the company and the company would look after you, but things weren’t like that anymore.