Yves here. As much as it would be a very positive development for Congress to stop deferring to the Executive Branch, I’ll believe it when I see it.

By Sarah Burns, Associate Professor of Political Science, Rochester Institute of Technology. Originally published at The Conversation

In mid-July 2021, a bipartisan and ideologically diverse group of senators proposed a new bill that, if passed, would dramatically shift the relative amount of power the president and Congress have over U.S. military operations.

Whether this bill passes as is, or with significant changes, or not at all, its proposal signals an effort by lawmakers to reclaim power over military action and spending that Congress has gradually surrendered over decades. It also puts pressure on presidents to evaluate their foreign policy objectives more clearly, to determine whether military action is, in fact, appropriate and justified.

As I’ve demonstrated in my research, even though the 1973 War Powers Resolution attempted to constrain presidential power after the disasters of the Vietnam War, it contains many loopholes that presidents have exploited to act unilaterally. For example, it allows presidents to engage in military operations without congressional approval for up to 90 days.

As a result of this shift from legislative oversight to presidential control, U.S. foreign policy has become less deliberative and administrations from both parties enjoy a significant amount of control over whether the U.S. calls in the armed forces to address developments overseas.

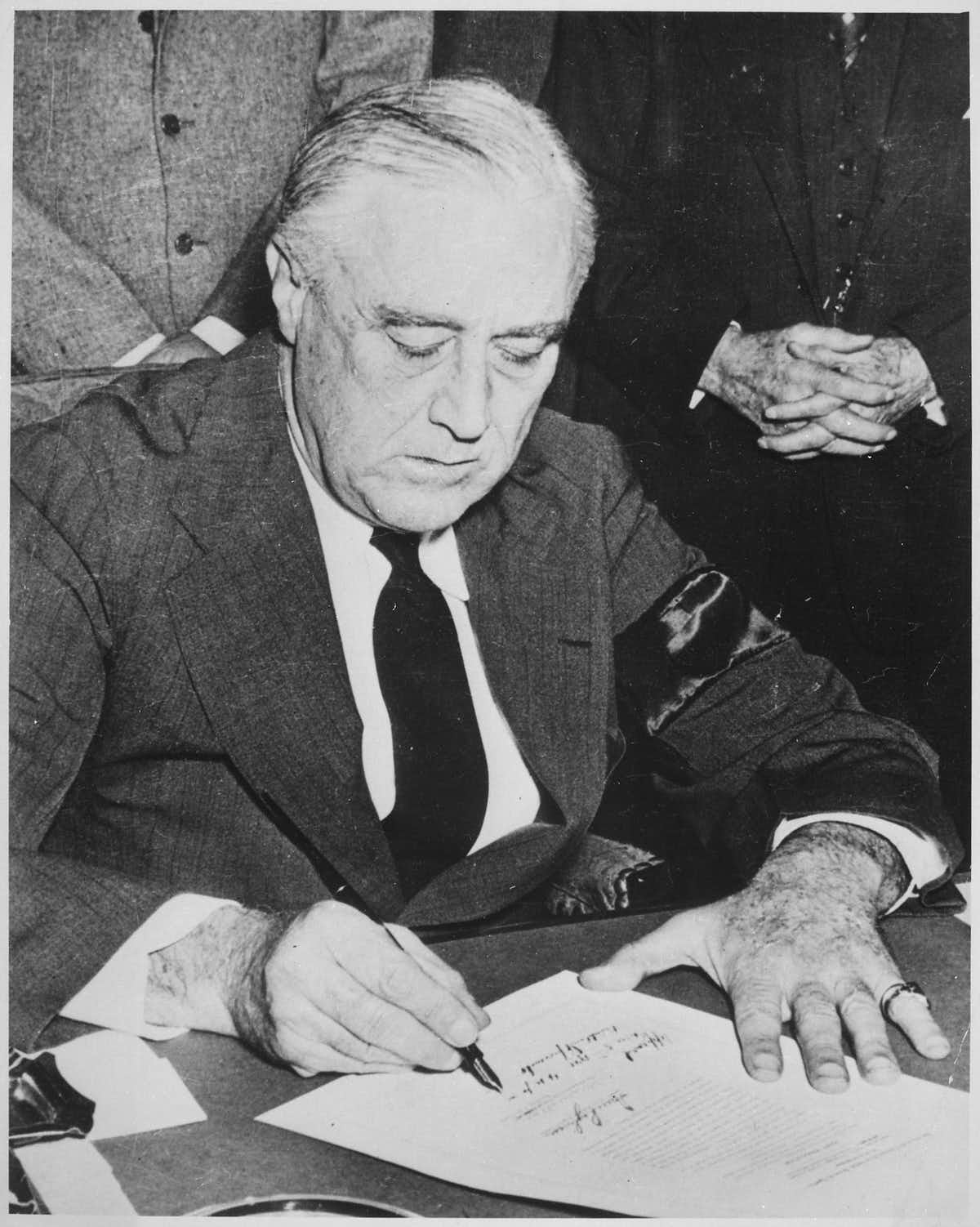

This bill would end that loophole, requiring presidents to explain their actions more clearly to Congress and the public. Since Franklin D. Roosevelt, presidents have attempted to circumvent oversight and restraints from Congress by citing vague concerns like “national security,” “regional security” or the need to “prevent a humanitarian disaster,” when launching military operations. But they haven’t typically given Congress more concrete information about the nature of the operation or its expected duration.

The new bill sets out a clear definition of which military activities need to be reported to Congress, and how quickly. This is especially important given the ambiguities that prior administrations have exploited. In 2011, a State Department lawyer argued that air strikes in Libya could continue beyond the War Powers Resolution’s 90-day time limit because there were no ground troops involved. By that logic, any future president could carry out an indefinite bombing campaign with no congressional oversight.

The bill would also require the president to provide an estimated cost of the operation and describe the mission’s objectives – both of which could help Congress determine whether a military operation had stayed within its intended bounds or gone beyond them.

Executive Power Grows

Before the Pearl Harbor attack forced the U.S. into World War II, Congress had exercised its war powers, preventing President Franklin D. Roosevelt from joining Britain, Australia and other nations in battle.

But in the wake of the attack, Congress began giving the president more control over the military, engaging in less oversight for fear of being painted as undermining the war effort.

After World War II ended, unlike in previous eras, Congress continued to relinquish those powers, largely by declining to rein in presidential actions that overstepped into congressional power.

Congress never authorized the war in Korea; Harry Truman used a U.N. Security Council resolution as legal justification. Congress’ vote explicitly opposing the invasion of Cambodia didn’t stop Richard Nixon from doing it anyway. Even after the Cold War, Bill Clinton regularly acted unilaterally to address humanitarian crises or continuing threats coming from leaders like Saddam Hussein.

After 9/11, Congress gave up more of its power much faster. A week after those attacks, Congress passed a sweeping Authorization for Use of Military Force, giving the president permission to “use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001.”

In a followup 2002 authorization, Congress went even farther, allowing the president to “use the Armed Forces … as he determines to be necessary and appropriate in order to defend national security” and “enforce all relevant United Nations Security Council resolutions regarding Iraq.”

In the two decades since their passage, four presidents have used those authorizations to justify all manner of military action, from targeted killings of terrorists to the years-long fight against the Islamic State group, which continues to this day. This approach provides few, if any, congressional checks on the control of military affairs exercised by the president.

Threats of War

The Biden administration has called for more congressional oversight of military actions, saying the powers granted in 2001 and 2002 were too broad and invite abuse by power-hungry presidents.

And yet Biden has said he did not need anything beyond the Constitution to launch attacks in Syria in February and June 2021, saying he was doing so to defend U.S. forces. In mid-July 2021, Biden used the authorizations’ power to launch a drone strike in Somalia against fundamentalist al-Shabab fighters.

But perhaps the most frightening use of these broad authorities was in January 2020, when President Donald Trump used the 2002 authorization to justify a lethal drone strike against a respected member of the Iranian government, Major General Qassim Soleimani, without consulting Congress or publicly explaining why the attack was necessary, even to this day.

The killing of Soleimani, who held a position in Iran equivalent to the director of the U.S. CIA, was described by the Trump administration only as “decisive action to stop a ruthless terrorist from threatening American lives.” Trump’s subsequent promises that Iran would “never” have a nuclear weapon were also backed up by the idea that Congress had effectively authorized him to take military action against Iran’s nuclear program.

Tensions – and fears of war – spiked but then slowly faded, when Iran responded with missile attacks on two U.S. bases in Iraq, and Trump downplayed the severity of resulting injuries to American service members. But Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Hosseini Khamenei has continued to vow to get revenge for Soleimani’s killing, leaving open the possibility of an Iranian attack at any time. Under the current legal structure, a U.S. response to that could come without congressional notification or approval.

The current congressional effort is noteworthy because it seeks to make presidents answerable to Congress for a wider range of military action, and to end the broad and sweeping power of the 2001 and 2002 authorizations that have effectively let presidents do anything with the U.S. military anywhere in the world without being held accountable at home.

It’s SO NICE to see the Congress making a gesture in support of the Constitution and the Rule of Law..

Was their middle finger extended?

After reading your post, I do believe that “ Their middle finger was extended “ ALL THE WAY ( emphasis mine) The USA constitution is crystal clear on what body has the power to go go war; It is in plain view for any one to see. On article 1, section 8, close 11 unequivocally states that “ CONGRESS SHALL DECLARE WAR “ If congress people do not see this, is because they don’t want to.

“…perhaps the most frightening use of these broad authorities was in January 2020, …”

What about the 2003 Iraq War itself? that was by far more frightening AND (imo) the biggest US strategic military/diplomatic error since at least 1946.

Amazing how 2003, and its bipartisan enablers (including Schumer, Daschle, Pelosi, Hoyer) have been whitewashed

from the zeitgeist and replaced with a convenient hagiography.

Well, the legislation might help rein in Presidents’ war-making, but how about impeaching and prosecuting Presidents who later violate this new, proposed law? And how about not giving (through a reduction in military spending) the War Department so many more new toys to “play” with?

this sounds nice, but that congress in recent decades has rarely seen anything happen on the world stage that it didn’t want to bomb into submission, so the effect remains the same, no?

I can understand during the Cold war having the President having war powers when you consider in the event of a nuclear attack, that there would be only minutes to make any decisions. But since the Cold War ended what – thirty years ago, this is just Congress doing a dereliction of duty of what is stated in the US Constitution. Funny that. A lot of America’s worse problems seems to stem from when it strays from following the principles of that old document. I can guess what will happen here though. A law will be proposed to make it more (supposedly) difficult for a President to make war on a country but after it is pushed through Congress, it will actually give him a blank check to do whatever he wants. How about they make the US Supreme Court make a ruling on what it says in the US Constitution and force the President and Congress to actually do it? It might be simpler.

Lots to consider here, particularly given the Authorization to Use Military Force, the continuing disproportionate influence of the neocons in the current administration, and their ongoing effort to maintain and even intensify tensions with particular foreign governments. Good to see Congress beginning to rein in executive branch actions that have led to the loss or impairment of so many lives and our national treasure.

As with Congress ceding national economic policy to the neoliberal monetarists at the Fed despite the self evident failure of “Quantitative Easing” to lead to broad-based economic growth, I expect restoration of the war powers to Congress might necessitate a reversal of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision regarding political campaign financing. That in turn depends in large part on the congressional leadership of both legacy political parties, who I think view MIC and Wall Street funding as key to maintaining their legislative influence through control of the purse strings, and will therefore quietly acquiesce to maintaining the status quo of vesting military conflict powers in the executive branch. Hopefully I ‘m wrong and this Senate initiative will gain sufficient political traction.

I can only hope US warmaking will halt or at least slow down. Congressional restraint of the President — somewhat like that described in the US Constitution would be nice — some sort kind of balance of power. But I believe neither the Congress nor the President have demonstrated much wisdom or restraint in warmaking.

If Congress has a todo list for reining in US madness in world affairs, I believe they might add to that list some laws to sever ties between the ever growing Intelligence Industrial Complex and the State Department, combined with an effort to rebuild a State Department capable of diplomacy. Then I recall that war is racket and the racketeers appear in full control of all three branches of the US Government, and my initial hope evaporates.

I like how the excuse to go to war in Korea was based on the UN resolution (which USSR at that boycotted) but then when the UN voted against the second Iraq war, the US said screw you world… International rules based order = My way or the highway…

It is strange that the article seems not to touch on the crux of the matter, a constitutional power dispute between the branches, regardless of lesser laws. If the current status quo of presidential usurpation of the congress’ war power is to be overcome, it will need to be via amendment, not law.

https://sherman.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/congressman-sherman-introduces-war-powers-act-enforcement-act

Which agreement places many constitutional scholars at odds with the plain text of the constitution as article 1, section 8 gives the war power to congress.