Yves here. I do not like flying on full airplanes even though the airline industry is very keen to fill seats after Covid whackage. Hubert Horan explains why the idea of airline recovery is considerably overhyped.

By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines). Horan currently has no financial links with any airlines or other industry participants

US Airlines Began Achieving Revenue Gains in Second Quarter That Were Unavailable to Non-US Airlines

To understand the ongoing airline crisis, one must keep in mind the major difference between the US based carriers and carriers in the rest of the world. US airlines have the advantage of a huge domestic market that has been free of the explicit barriers that has crushed most cross-border travel demand, and where widespread vaccine distribution has encouraged consumers to travel.

US airlines have also disproportionately benefitted from taxpayer bailouts compared to airlines in the rest of the world. The principal objective of the $65 billion in subsidies provided to the US industry to date was to protect incumbent shareholders and senior executives from having to bear the costs of the major restructuring required after the massive coronavirus demand collapse, and to enable those shareholders and executives to reap the benefits from post-pandemic equity appreciation. Airlines in other countries either received no subsidies and had to file for bankruptcy or had to grant taxpayers significant (or even majority) equity positions in return for financial assistance. [1]

The second quarter financial results that the US carriers recently released show industry financial gains entirely dependent on domestic leisure demand and those taxpayer grants. The catastrophic losses the industry recorded in 2020 when it was flying nearly empty airplanes have subsided, and the second quarter saw a major jump in domestic demand that brought the industry within sight of breakeven. Second quarter domestic passenger revenue was $16.8 billion, double the $8.4 billion the first quarter level.

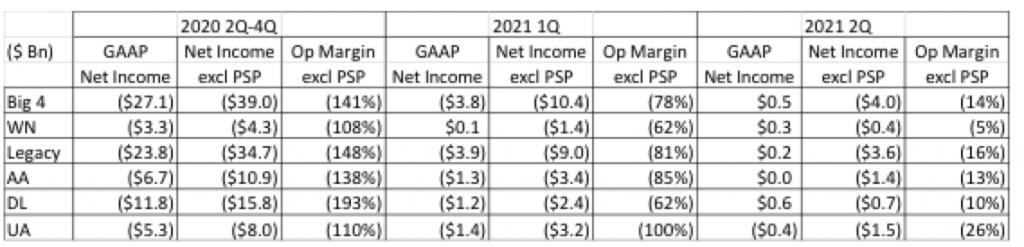

The airlines’ second quarter financial press releases claimed their operations were now profitable, but accounting profits were entirely due to those gifts from taxpayers. The Big 4 airlines (Southwest, plus the three large Legacy network carriers American, Delta, United, which account for over 85% of the total US airline industry) report Payroll Support Program (PSP) grants (roughly one-third of the subsidies US taxpayers have provided) on their P&L statements as operating income gains, akin to increased ticket sales or improved efficiency. These PSP grants improved Big 4 P&Ls by $11.9 billion in 2020 and by $11.1 billion in the first two quarters of 2021. [2] Excluding PSP grants, the Big 4 had GAAP losses of $10.4 and $4.0 billion in the first two quarters.

The US Carrier Finances Have Improved but Have Not Recovered

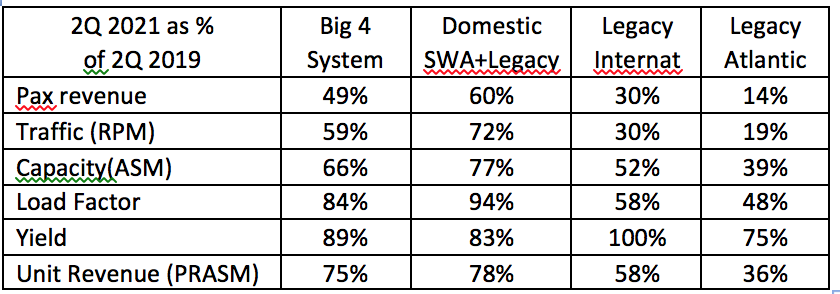

The table below illustrates that the US industry is still a considerable distance from restoring pre-pandemic conditions. The second quarter gain is a noteworthy improvement but domestic revenue in 2Q21 was still only 60% of the second quarter of 2019. Airlines are now filling their domestic flights at close to 2019 levels, but they are only operating 77% of 2019 capacity, and are only achieving 78% of the unit revenues that capacity had earned two years ago. In 1Q21 the industry’s domestic revenue was only 35% of the first quarter 2019 level, and unit domestic revenues were only 60% of 1Q19 capacity earned.

The rapid recent growth has been dominated by the pent-up leisure demand from relatively wealthy flyers who had been unable to visit friends or vacation spots in 2020 and responded to the industry’s aggressive pricing. It is likely this demand will remain strong in the third quarter but ongoing growth will depend on whether leisure demand continues to grow once the market recognizes that planes are full and the bargain fares on offer earlier this year have disappeared.

Full recovery of the domestic market will require the return of the corporate travel that paid the higher fares critical to industry profitability. While corporate travel will undoubtedly increase above its still depressed level, there are reasons to believe 2019 demand levels might never return. Many companies have discovered during the pandemic that they were able to function with a vastly reduced number of business trips, and that the high fares they historically paid might not have been justified. [3]

The biggest industry problem is that a meaningful recovery of international revenue is not on the near-term horizon. 2Q21 international traffic and revenue was still only 30% of 2Q19 levels, and much of this was leisure traffic to Mexico and the Caribbean. Revenue in the transatlantic market (historically the industry’s most profitable market) is only 15% of pre-pandemic levels and transpacific revenue (not shown in the table) remains similarly depressed.

Similar patterns are seen outside the US. European airlines are operating 93% of their pre-pandemic domestic capacity this summer and 61% of their short-haul intra-EU flights. But their bread-and-butter intercontinental services remain decimated, with only 34% of North Atlantic and 26% of Asia Pacific capacity scheduled this summer. [4] The problem is that (except in China) domestic markets outside the US are too small to generate the revenue intercontinental airlines need to stay afloat.

Since we don’t know how issues like the Delta variant, the uncertain duration of vaccine protections, vaccine hesitancy and distribution problems, and Long Covid will play out, the future of the airlines that depend on international traffic will remain problematic. Closed borders and quarantines have been the most effective ways to limit the spread of the virus. Given increased transmission rates, the industry’s optimism that international demand would soon show the same type of rebound seen in US domestic markets is clearly misplaced.

The industry’s various proposals for working around cross-border restrictions never made any sense. “Airbridges” were proposed as a way to kickstart travel between countries such as the US and UK, but it was never explained why passengers given special exemption from testing and quarantine rules would not pose health risks. Airlines continuously talked about establishing “vaccine passports” without ever explaining how the enormous data and security systems needed could be established, or how a wide range of governments would reach agreement on rules and how to enforce them. [5]

The Outlook for US Industry Will Be Driven by International Issues

It is useful to keep in mind that the outlooks presented by airlines and the media since the beginning of the crisis have been consistently wrong, All industry forecasts in mid-2020 predicted that a major rebound in corporate and international traffic would have been fully underway by the fourth quarter of last year. [6] “Industry analysis” continues to largely consist of magical thinking about the inevitable return of 2019 market conditions. Recent suggestions that domestic demand has “recovered” and an international recovery will soon follow means that airlines won’t need any painful restructuring to cope with changed market and competitive conditions.

Another major problem with coverage of the US industry is the longstanding myopia in America equating domestic flights with “the industry” and the inability of most US observers to understand the critical differences between domestic and international markets. Because of this there is little understanding of how the pandemic badly disrupted the longstanding structure of US airline competition.

Longhaul intercontinental markets have long been the primary drivers of airline profitability, and the three Legacy carriers had structured their megahub based networks to focus on them. The megahubs (Newark, Atlanta, Minneapolis, Chicago, Dallas-Ft. Worth) served to funnel interior US traffic to international flights and were only viable in domestic markets because of the airlines’ overwhelming dominance of traffic at the hub city. Even though the majority of Legacy capacity is nominally “domestic” their business model are designed to serve international traffic, and their corporate value depends on their international competitiveness and profits.

Southwest’s “Low-Cost” business model, had no intercontinental service and was optimized for large domestic markets turned out to be ideally suited to cope with the pandemic crisis. With much less focus on hub connections, Southwest could easily shift capacity to whatever markets had the greatest revenue potential, and as the P&L data shows, Southwest suffered less than the Legacy carriers after the initial 2020 demand collapse, and its traffic and financial recovery has been stronger.

One simple explanation for the industry’s pre-pandemic profitability is that the Legacy carriers recognized that their business model had strong competitive advantages in certain (international, megahub) markets and was largely uncompetitive in other (high-volume domestic) markets. Southwest has always focused on markets where it had sustainable competitive advantages and avoided the markets where the Legacy carriers were clearly stronger. A parallel industry structure exists in Europe where intercontinental carriers (KLM, Lufthansa) and short-haul low-cost operators (Ryanair, Easyjet) focus on entirely different demand segments, even though they sometime serve the same routes.

The pandemic destroyed this profitable dynamic. The Legacy carriers lost their most profitable business and, desperate to generate cash, diverted capacity into any domestic market where revenue might exceed the marginal operating costs. Instead of segregating markets based on business models (Legacy/Low Cost) or geography (Atlanta vs Dallas) all four carriers were now trying to be the type of purely short-haul domestic airlines that Southwest had always been.

But myopic US observers had always mistakenly seen the Legacies as primarily domestic airlines, and didn’t understand their cost structure was entire inappropriate for a purely short-haul domestic operation. American, Delta and United were not just making marginal adjustments to what they had always been doing (e.g. more flights to Sarasota and Bozeman) but were trying to become a totally different type of airline.

The industry predictions that the international and corporate demand recovery would have been well underway last year had been true, were based on wishful thinking that would allow the Legacies to quickly return to the what they had always done in the past and quickly restore the pre-pandemic competitive balance. But today’s reality is that international traffic will remain seriously depressed until virus suppression allows governments to eliminate cross-border restrictions, and even then might never return to historic levels. Similarly, corporate travelers might never be willing to spend as much on travel as they used to.

The Legacy carriers’ pre-pandemic business models won’t work unless 2019 market conditions return. Legacy networks costs, fleet capacity and infrastructure will be out of whack with their revenue potential and competitive situation. Fixing these problems will be extremely difficult. These strategic challenges will come on top of the potential for steadily increases in fuel and labor costs. The industry will also have to repay the staggering level of debt added since the crisis began, with the obvious risk that the extremely favorable interest rate environment may not last. [7]

In a truly competitive environment, these structural changes would likely force a major contraction of Legacy capacity and allow Southwest (and other purely domestic carriers such as Frontier and Spirit) to grow more rapidly. But the taxpayer subsidies badly distorted competition, allowing all three Legacies to maintain their market positions despite their staggering losses, while they continued to hope that the impacts of the virus and border closings would somehow magically disappear.

United appears to have the most sober understanding of the demand collapse of any US airline, and the greatest awareness that it may need to completely rethink its historical business model. It has taken major steps to fix major fleet issues but its historic network creates short-term revenue disadvantages. It has been more conservative about entering markets where it wasn’t historically strong but has lost market share as a result. [8]

Delta is in the opposite situation. Its complete domination of its megahub markets (Minneapolis, Detroit, and most importantly Atlanta) gives it a short-term revenue advantage, but it is not clear whether it understands that the value of its network is much lower in a world with significantly smaller international and premium business demand. Delta had come to believe that its pre-pandemic yield and stock market premiums were the result of its superior management while in reality most were due to long-ago fortuitous network and industry consolidation events. As a result Delta appears to be especially invested in the belief that the 2019 market conditions will magically return. [9]

When the crisis hit American quickly recognized that domestic expansion would be key to cash generation, and now offers 15% more domestic capacity than Delta and Southwest and 60% more than United. While logical in the short-term, a plan for longer-term competitiveness and profitability has yet to emerge, and American has, far and away the worst balance sheet in the industry.

___________

[1] For details of the 2020 industry bailout see Hubert Horan: What Will it Take to Save the Airlines? Naked Capitalism 3 June 2020. For the 2021 bailout see Hubert Horan: The Airline Industry Collapse Part 6 – U.S. Airlines Lost Over $35 Billion in 2020. Naked Capitalism, February 22, 2021. The congressional funding granted the major airlines a “too-big-to-fail” put that ensured access to capital markets by eliminating the risk that companies losing billions of dollars might have to file bankruptcy. For a broader discussion of how the taxpayer bailouts were designed to protect the incumbent shareholders and senior managers, and allowed airlines to avoid dealing with ongoing efficiency problems see Hubert Horan, The Airline Industry after Covid-19: Value Extraction or Recovery? American Affairs Journal, Spring 2021, pp.37-68. https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2021/02/the-airline-industry-after-covid-19-value-extraction-or-recovery/

[2] Smaller airlines also received PSP grants and additional PSP grants will be recognized in the third quarter. Other major CARES Act subsidies (such as loans at below market rates) are noted in SEC filings but do not directly improve the P&L results shown in the table.

[3] Wolf Richter, Slowly But Not Surely: Airline Leisure Travelers Coming Back, But Not Business Travelers. International Still Crushed, Wolf Street, May 17, 2021

[4] Centre for Aviation, European aviation: recovery yet to embrace North America, Asia Pacific, 20 July 2021

[5] Benjamin Katz, U.K. Carriers Push Air Bridge to U.S. Amid Vaccination Success, Wall Street Journal, April 6, 2021. Maria Carnovale, Can Vaccine Passports Actually Work? Slate, July 14, 2021. None of the passport proposals ever explained how governments would decide whether a passport was acceptable (which vaccines? How recent?) or who would pay for and manage the systems needed to verify passports. Collecting and maintaining reliable vaccine data would be totally impossible in America and forging the documents issued in America is child’s play.

[6] Hubert Horan, The Airline Industry Collapse Part 3 – Recovery Expectations Were Always Dreadfully Wrong, Naked Capitalism, August 4, 2020

[7] Centre for Aviation, How can we expect a sustainable industry built on junk bonds?, April 14, 2021

[8] Niraj Chokshi, United Airlines Plans a Record Fleet Expansion as Travel Rebounds, New York Times, June 29, 2021. United acquired 270 737-Max and A321-Neo aircraft and will retire 200 50 seat regional jets. The increased gauge and fuel efficiency will fix cost problems that date to United’s bankruptcy and its merger with Continental. Unlike Delta, all of United’s hubs face a significant local competitor (e.g. American and Southwest in Chicago, Southwest in Houston)

[9] For the history of the industry consolidation that created most of Delta’s yield and share price premiums see my American Affairs Journal article. For current Delta management expectations that market conditions will fully recover and that it will soon be able to return to its pre-pandemic strategies see Holly Hegeman, Plane Business, July 20, 2021.

On the European side of things, Ryanairs share prices went up as they announced a surge of bookings (although mostly at very low fares). Easyjet, a UK based discount airline also announced an increase (and they are still investing heavily in hotels associated with cheap breaks). My guess is though that this third quarter surge is largely based on the new EU vaccination passport and doesn’t have legs.

I wonder if its really sunk in with the airlines that the ‘other’ Delta means we will be living with Covid into 2022 at least. And there must be the possibility that the penny will finally drop with countries that even with high vaccination rates, allowing too much travel is simply asking for trouble when it comes to new varients.

Horan mentions the dynamic between the distinct business models of the discount short haul airlines and the legacy airlines, but there is an important third player – the lease companies. If they are forced to drop prices significantly due to oversupply I think we could see a wave of new entrants to the airline business, all using cheap leases (or sometimes buying up surplus used aircraft at super cheap prices) as a way of undercutting existing players.

Its worth noting that foreigners are not allowed to own airlines in the US.

Alas, this looks like the only intercontinental flying I’ll be doing any time soon

“The principal objective of the $65 billion in subsidies provided to the US industry to date was to protect incumbent shareholders and senior executives from having to bear the costs of the major restructuring required after the massive coronavirus demand collapse, and to enable those shareholders and executives to reap the benefits from post-pandemic equity appreciation”

Socialists.

Neoliberals and conservatives aren’t against socialism.

They are for socialism for corporate executives, Wall Street, and to a degree, the upper middle class, although they would very much prefer all the gains go to the very rich.

It’s only when socialism that benefits the poor that they get worked up.

I’m not an expert on these semantics but, as amusing and thought-provoking as the ‘socialism for the rich’ meme can be, I feel like there’s probably more to socialism than ‘free money’.

you’re right, it’s free money and control of the levers of power such that as a class they rarely suffer.

Another good analysis from Horan. But I wonder why his list of “megahubs” does not include airports like JFK, LAX and MIA?

“Megahub” from a specific airline perspective. United at ORD, Delta at ATL, etc.

A data point that is important in understanding the airline industry in any context is that when one ignores subsides (air mail in the early days, subsidized airports, etc.) the airline industry has not generated a profit throughout its history.

The assumption that the airline industry can operate without subsidy is flawed.

The same applies to modern fractional reserve banking, but that is an argument for another day.

From the perspective of someone who rarely flies shouldn’t the above be regarded as a good thing? These days we constantly hear talk of how the world has to change from its pre AGW heedlessness. And yet surely nothing is more heedless than the huge increase in air travel of the late 20th century–so much of it purely discretionary. By this way of thinking the goals of the airline business are directly opposed to the goal of reducing global warming. And the travel and tourism business has even begun to degrade its own attractions as must see icons like Venice or the Louvre or our own national parks are overrun by tourists. Maybe belonging to the “jet set”–that status marker beloved of the elites–should be regarded as uncool if we are really serious about saving the rest of nature.

Just a thought.

And a good thought too. I was just wondering yesterday if the reduced amount of flying over the past year or so has had any effect on our atmosphere. And to think that you had fish returning to the canals of Venice last year. I wonder if the latest influx of tourists has cleared them out again. But agreed that the emphasis on global tourism directly contradicts the goal of reducing global warming.

I’ve loved the clear skies for the past year – the occasional contrail now seems very intrusive, when once they just seemed part of the evening sky.

Yes, and so have the homeowners near LAX. The pandemic has shown them a much quieter living environment. These folks fought for and won some measure of mitigation as the number of flights have increased the past few months: sound abatement and sound-proofing of their homes that will cost the airport 100’s of millions of dollars.

Amazing what people recognize when the “music” stops.

Carolinian: Surely nothing is more heedless than the huge increase in air travel of the late 20th century…Maybe belonging to the “jet set”–that status marker beloved of the elites–should be regarded as uncool if we are really serious about saving the rest of nature. Just a thought.

It’s a thought. In the real world, though, 7.1 gigatons per year of greenhouse gas emissions — 14.5 percent of all global greenhouse gas emissions — come from cattle agriculture.

Interestingly, too, not every country is producing an even split of that 14.5 percent. India, it turns out, has the world’s largest cattle population, but the lowest beef consumption of any country. Thus, cows in India live longer and emit more methane over their lifetime. Annually, one cow can belch or fart 220 pounds of methane.

See: -“Tackling Climate Change Though Livestock”

from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

http://www.fao.org/3/i3437e/i3437e.pdf

By contrast, global aviation (domestic and international; passenger and freight) accounts for only 1.9 percent of greenhouse gas emissions (including all greenhouse gases, not only CO2), 2.5 percent of CO2 emissions, and 3.5 percent of ‘effective radiative forcing’ – a closer measure of its impact on warming.

We could certainly do useful things like moving freight air transport over to some 21st century from of dirigible networks, and intra-US air travel could be much reduced by the construction of modern rail systems as in China and Europe (though this is likely beyond the capabilities of a backward, corrupt state like the US).

The point is, nevertheless, air travel is almost a rounding error in the larger scheme of things.

> air travel is almost a rounding error in the larger scheme of things.

Not when you consider the role of air travel in bringing superspreaders across borders.

Right. There’s also the overtourism problem that I mentioned (does the whole world really need to go look at the Pyramids out their bus window) and the Al Gore mansion problem. That latter is where the elites kvetch about the lowers turning up their noses at public transportation while themselves jetting around the world at the drop of a hat.

Al Gore justified his energy sucking house by saying he had bought carbon offsets, perhaps from some hut dweller in the Congo. Making global warming the “little people’s” problem is not the way to inspire cooperation or even belief. Their mansions and their lifestyles and their big limos and yachts are sending the opposite message.

But here in America even people who aren’t particularly wealthy use far more energy than they need to do. The goal of growth, fretted about by the airlines and capitalism in general, goes against the goal of conservation.

Fine as far as the utilisation of existing lines. We’re stuck with them. But too often, ‘modern’ rail systems are taken to mean the construction of brand new scars across the landscape like the Japanese Shinkansen and Johnson’s HS2 vanity project so that the rich and businesslike can forego air travel over short hops without losing any of their precious time.

We need to re-learn that time is precious, and should be taken slowly.

Thank you for providing a link to the FAO report itself. That’s a long report. It would take many hours to read. Scanning the table of contents makes me wonder whether people who report about the report are really relaying everything the report actually says, or even some of its basic meanings.

How much carbon-as-methane do cattle-on-pasture/range systems emit versus how much carbon-as-CO2 do cattle-on-pasture/range systems suck down and bio-sequester? How much carbon-as-methane do cattle on corn-soy feedlot emit as methane plus how much carbon-as-CO2 do the cattle on corn-soy feedlot also emit because of the CO2 emitted to supply and run the feedlot system?

How much methane does the floodwater paddy rice system emit compared to how much methane the cattle emit?

Termites emit methane. How much methane do all the termites of the world emit?

How much methane do all the leaky gas pipelines and wells and abandoned wells emit?

In other words, what percent of the world’s methane emission comes from cattle as against from non-cattle sources? Is methane from cattle a real problem or a diversionary decoy issue?

Is it? Who told you that? An airline sales rep?

https://www.dw.com/en/to-fly-or-not-to-fly-the-environmental-cost-of-air-travel/a-42090155

Taking all greenhouse gases into consideration, aviation is responsible for about 5% of global emissions. But that’s not because emissions from aviation are low, it’s because it serves a very small proportion of people: less than 10% of the world’s population has ever been on a plane. Here in the West, where we fly a lot, flights make up the largest part of our carbon footprints.

Wishful thinking?

How about denial? 2 of the 3 existential Cs partially addressed: Covid and Capitalism

When factoring in Climate Change, which appears to be evolving as quickly as Covid (while neoliberal Capitalism doubles down) it looks pretty bleak.

The Biden administration just declined to lift the ban on Europeans entering the country. This will be another spanner in the works for the legacy carriers.

Off topic, but I am eager to see an update on Uber.

One is coming!!!

Excellent!

Yayy!