Yves here. While this post provides an important example about how water is becoming a political, and even a geopolitical flash point, it fails to mention the big reason the US is making such heavy demands on the Colorado River: often profligate water use by the California agriculture industry. California grows almonds, even though the water cost of a single almond is a gallon. Other nuts require similar high water rations, but almonds are far and away the most popular.

Astonishingly, California produces 17 varieties of rice. Avocados and bananas are also water hogs.

By Robert Gabriel Varady, Research Professor of Environmental Policy, University of Arizona; Andrea K. Gerlak, Professor, School of Geography, Development and Environment, University of Arizona; and Stephen Paul Mumme, Professor of Political Science, Colorado State University. Originally published at The Conversation

The United States and Mexico are tussling over their dwindling shared water supplies after years of unprecedented heat and insufficient rainfall.

Sustained drought on the middle-lower Rio Grande since the mid-1990s means less Mexican water flows to the U.S. The Colorado River Basin, which supplies seven U.S. states and two Mexican states, is also at record low levels.

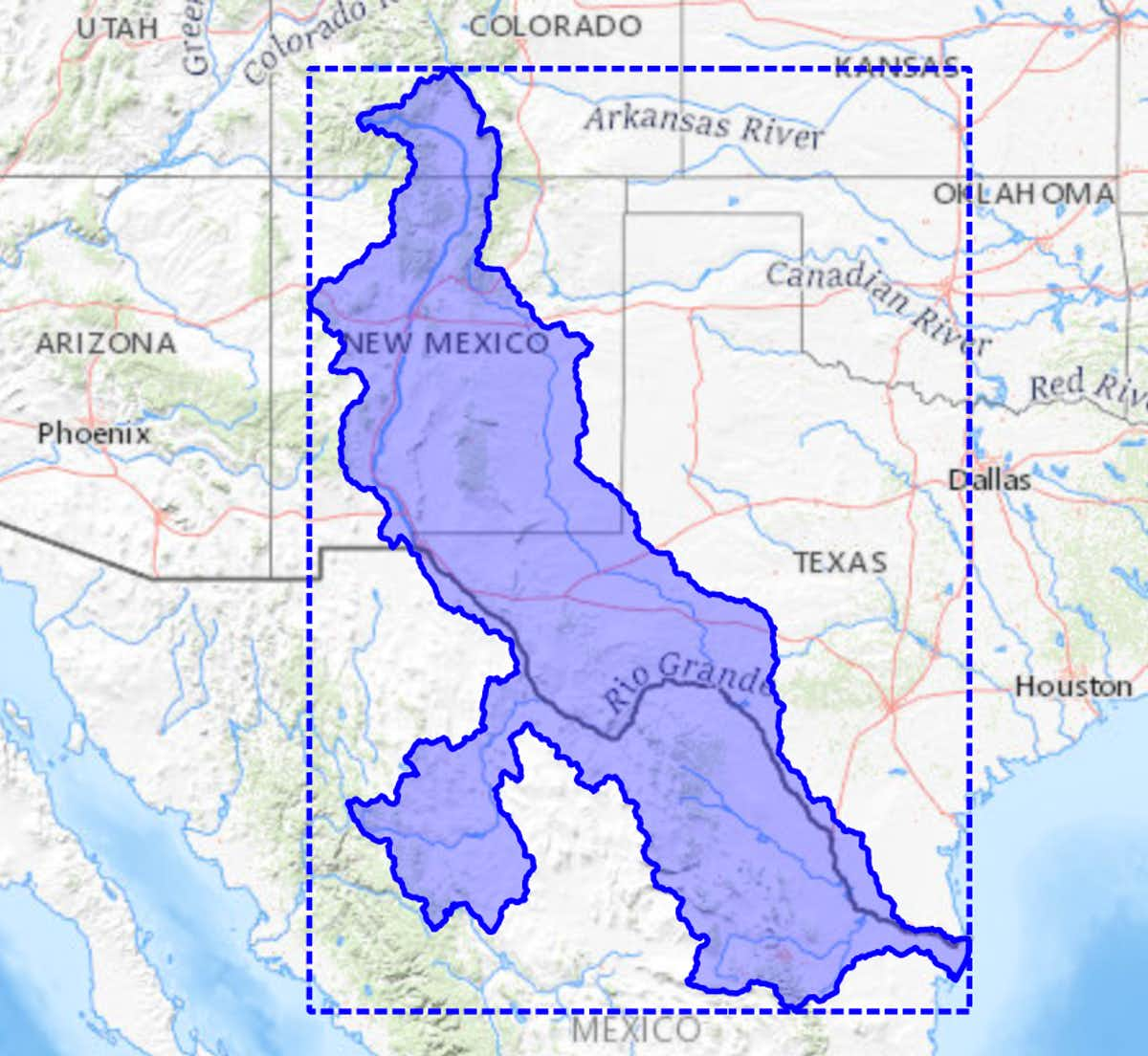

A 1944 treaty between the U.S. and Mexico governs water relations between the two neighbors. The International Boundary and Water Commission it established to manage the 450,000-square-mile Colorado and Rio Grande basins has done so adroitly, according to our research.

That able management kept U.S.-Mexico water relations mostly conflict-free. But it masked some well-known underlying stresses: a population boom on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, climate change and aging waterworks.

1944 to 2021

The mostly semiarid U.S.-Mexico border region receives less than 18 inches of annual rainfall, with large areas getting under 12 inches. That’s less than half the average annual rainfall in the U.S., which is mainly temperate.

The 1940s, however, were a time of unusual water abundance on the treaty rivers. When American and Mexican engineers drafted the 1944 water treaty, they did not foresee today’s prolonged megadrought.

Nor did they anticipate the region’s rapid growth. Since 1940 the population of the 10 largest pairs of cities that straddle the U.S.-Mexico border has mushroomed nearly twentyfold, from 560,000 people to some 10 million today.

This growth is powered by a booming, water-dependent manufacturing industry in Mexico that exports products to U.S. markets. Irrigated agriculture, ranching and mining compete with growing cities and expanding industry for scarce water.

Today, there’s simply not enough of it to meet demand in the border areas governed by the 1944 treaty.

Three times since 1992 Mexico has fallen short of its five-year commitment to send 1.75 million acre-feet of water across the border to the U.S. Each acre-foot can supply a U.S. family of four for one year.

Water Conflicts

In the fall of 2020, crisis erupted in the Rio Grande Valley after years of rising tensions and sustained drought that endanger crops and livestock in both the U.S. and Mexico.

In September 2020, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott declared that “Mexico owes Texas a year’s worth of Rio Grande water.” The next month, workers in Mexico released water from a dammed portion of Mexico’s Río Conchos destined to flow across the border to partially repay Mexico’s 345,600-acre-foot water debt to the U.S.

Frustrated farmers and protesters in the Mexican state of Chihuahua clashed with Mexican soldiers sent to protect the workers. A 35-year-old farmer’s wife and mother of three was killed.

Mexico also agreed to transfer its stored water at Amistad Dam to the U.S., fulfilling its obligation just three days before its Oct. 25, 2020, deadline. That decision satisfied its water debt to the U.S. under the 1944 treaty but jeopardized the supply of more than a million Mexicans living downstream of Amistad Dam in the Mexican states of Coahuila and Tamaulipas.

The U.S. and Mexico pledged to revisit the treaty’s Rio Grande water rules in 2023.

The drought dilemma on the Colorado River is similarly dire. The water level at Lake Mead, a major reservoir for communities in the lower Colorado River Basin, has dropped nearly 70% over 20 years, threatening the water supply of Arizona, California and Nevada.

In 2017, the U.S. and Mexico signed a temporary “shortage-sharing solution.” That agreement, forged under the authority of the 1944 treaty, allowed Mexico to store part of its treaty water in U.S. reservoirs upstream.

Saving a Strained Treaty

Water shortages along the U.S.-Mexico border also threaten the natural environment. As water is channeled to farms and cities, rivers are deprived of the flow necessary to support habitats, fish populations and overall river health.

The 1944 water treaty was silent on conservation. For all its strengths, it simply allocates the water of the Rio Grande and Colorado rivers. It does not contemplate the environmental side of water use.

But the treaty is reasonably elastic, so its members can update it as conditions change. In recent years, conservation organizations and scientists have promoted the environmental and human benefits of restoration. New Colorado River agreements now recognize ecological restoration as part of treaty-based water management.

Environmental projects are underway in the lower Colorado River to help restore the river’s delta, emphasizing native vegetation like willows and cottonwoods. These trees provide habitat for such at-risk birds as the yellow-billed cuckoo and the Yuma clapper rail, and for numerous species that migrate along this desolate stretch of the Pacific Flyway.

The Rio Grande Basin. U.S. Geological Survey

Currently, no such environmental improvements are planned for the Rio Grande.

But other lessons learned on the Colorado are now being applied to the Rio Grande. Recently, Mexico and the U.S. created a permanent binational advisory body for the Rio Grande similar to the one established in 2010 to oversee the health and ecology of the Colorado.

Another recent agreement permits each country to monitor the other’s use of Rio Grande water using common diagnostics like Riverware, a dynamic modeling tool for monitoring water storage and flows. Mexico also has agreed to try to use water more efficiently, allowing more of it to flow to the U.S.

Newly created joint teams of experts will study treaty compliance and recommend further changes needed to manage climate-threatened waters along the U.S.-Mexico border sustainably and cooperatively.

Incremental treaty modifications like these could palpably reduce the past year’s tensions and revitalize a landmark U.S.-Mexico treaty that’s buckling under the enormous strain of climate change.

Water recycling by industry is badly needed. When you do the math the ROI for almost any cost of equipment should be in months. The fact that this is not a big industry might indicate that nothing works well. The rate limiting contaminant in water purification is t.d.s, and, the only widely used method for that is reverse osmosis. This uses membranes, which rapidly clog up, even more so when dealing with waste streams.

I keep harping on the fact that little to no organized R&D goes on in this field. Large companies in this space are dominated by conglomerates who need to use all available cash to pay off the hedge fund that spawned them. Meanwhile, the need for this has become urgent. I really doubt the public will notice a problem until air comes out of the tap

I don’t see how this treaty from what, three quarters of a century ago, can still work in a region which is undergoing climate change. And it won’t just be disputes between Mexico and the US but also between States such as Texas, Arizona, New Mexico and California. Several years before this treaty, Mexico nationalized the U.S. & Anglo-Dutch oil company known as the Mexican Eagle Petroleum Company which became the state-owned Mexican oil company Pemex. I wonder if this water treaty was signed as a sort of compensation for the nationalization of that oil company. To keep Washington off their case.

Texas already sued New Mexico AND Oklahoma over water issues in recent years. The New Mexico one was because Texas thought they were using too much water in the headwaters of the Rio Grande. Not sure where that one is in the courts.

The Oklahoma effort was to try and force them to go along with a deal Texas had with a tribe up there to get water destined for the Red River before it entered the river which keeps it a lot purer. I know that one tanked when the Okie leggy passed a law prohibiting such things.

I’ve mentioned the very good documentary The River and the Wall (2019) where five environmentalists travel from El Paso to the Gulf of Mexico via foot, boat and horse. It’s not about the water problem but gives a good overview of the Rio Grande and its environmental threats (at the time Trump’s wall being the main concern).

As far as water goes, as Yves points out, it’s greed versus common sense and that’s the reason politically connected growers get to produce almonds in California.

And pistachios, too. ( Helped by a politically connected ban against Iranian pistachios entering America, to the benefit of the ” Miami Cuban” Iranian pistachio growers in California.

Let’s not forget grapes.

It isn’t all doom and gloom here. Quoting from the monthly report I just received from Rainlog.org:

“Southeast Arizona stands out as typically being one of the driest areas in June and also typically seeing the earliest monsoon precipitation. The outlook for the next couple of weeks is favorable for the moisture sticking around and precipitation ramping up. The July precipitation outlook issued by the NOAA-Climate Prediction Center on June 30th indicates an increased chance of above-average precipitation for all of Arizona. This is an encouraging sign at this point to help take the edge off of the exceptional drought conditions firmly in place across the region. The outlook for August and September is a bit murkier, so we will have to wait and see how conditions evolve through July.”

Furthermore, there are plenty of us who are actively working toward solutions. I’m a longtime supporter and participant in the activities of this Tucson-based organization:

https://watershedmg.org/

My buddy from Tucson was just here and he told me something kind of shocking, in that he claimed Phoenix could cut off Tucson from water if push>meets<shove…

Heard of that particular happenstance?

An interesting question. Seems Tuscon has problems with its traditional ground water sources and water from the CAP–initially built to supply agriculture–is uncertain given the problems with the Colorado and Lake Mead.

kvoa.com/news/2020/12/10/adeq-announces-actions-to-protect-the-city-of-tucsons-drinking-water-supply/

The Central Arizona Project brings Colorado water from Lake Havasu through Phoenix to Tuscon.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_Arizona_Project

Here’s some more. While this article is a bit out of date it does inform us that

http://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona/2014/08/11/arizona-water-supply-drought/13883605/

And article I linked here the other day and that is current said that the Phoenix water situation is secure for now via the Salt River and groundwater. So unlikely that Phoenix would shut off the CAP in any case (if they have that power?), but if the Colorado runs dry then all bets are off.

If irrigated agriculture came to a total stop in the irrigated farmland Southwest and California? I don’t really think so.

California grows a lot of fun food. Without all the fun food from California and the Southwest, winter in Michigan wouldn’t be very much fun, foodwise. But Michigan could still survive on potatoes, cabbage, turnips, carrots, etc. etc.

Michigan potatoes are not as much fun as California pistachios. But they will keep you just as alive.