I don’t want to write about flags or hot dogs, or (for that matter) the battle of Gettysburg — long story short: The Slave Power got whipped by a better general and a better army — so I thought I would perambulate once more through the biosphere, and take a look at… prairie dogs. Prairie dogs are a keystone species, but, like beavers, they are ecosystem engineers, not apex predators. I’m on a bit of an ideological mission to distinguish keystone species from apex predators because of nonsense like this:

Early in the investigation, police found ‘troubling’ white supremacy rhetoric and statements [Nathan] Allen wrote, which included the superiority of the white race, about whites being ‘apex predators’ and drawings of swastikas, Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins said. Before Saturday’s fatal encounter, Allen wasn’t on her office’s radar. He was married, employed, had a Ph.D. and no criminal history, Rollins said.

I don’t want self-perceived or -proclaimed apex predators to think they are more important than they really are. Similarly, I want to de-emphasize the producer-consumer-predator model of “food webs” and “trophic cascades” as the royal road to understanding ecosystems because ecologies are more complex than that (although Silicon Valley, which is predatory to its very bones, would very much prefer to think of “ecosystems” in exactly that way, without actually naming the multiple forms of predation involved. Ditto some academic specialties and departments.) Ecosystem engineers very much fit under the Mr. Rogers rubric of “Look for the helpers,” unlike wolves, sharks, or cats in their less domesticated moments, dearly as we love them, and so prairie dogs are a good vehicle to lay down these markers. Here is a picture of two prairie dogs, to get the “cute” thing out of the way:

Prairie dogs (in baseball, “sod poodles“) are in fact not cuddly, so don’t go hang out with them, like idiotic Harvard frosh petting the squirrels in the Yard, or keep them as pets:

Prairie dogs may look a bit like actual Chicken McNuggets, but in reality they’re fast, skilled fighters armed with sharp claws and powerful teeth. “The worst animal bite I’ve ever gotten was from a prairie dog,” said Jessica Alexander, a program associate in [World Wildlife Foundation’s (WWF)] Northern Great Plains office. ‘It takes a while for black-footed ferrets [a prairie dog predator] to learn how to catch them. Prairie dogs fight back.”

Prairie dogs are social animals, sometimes highly social:

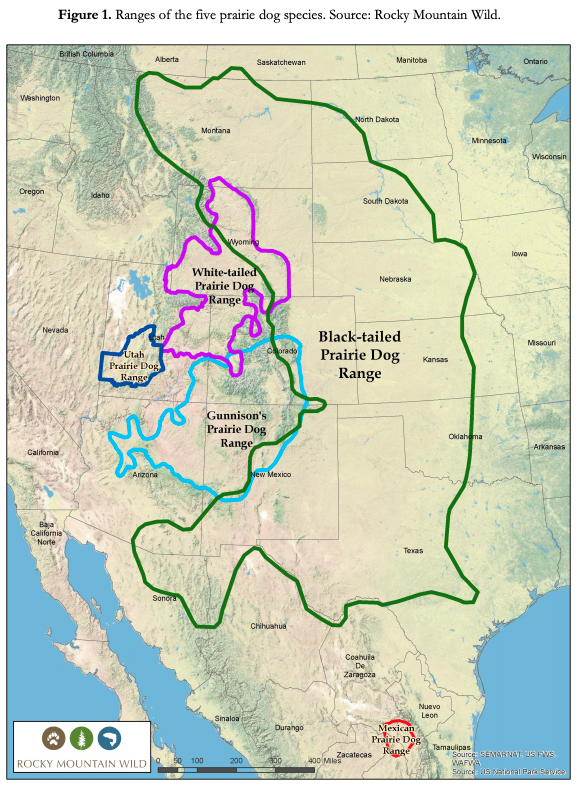

Black-tailed prairie dogs, the best known of the five prairie dog species, live in larger communities called towns, which may contain many hundreds of animals. Typically they cover less than half a square mile, but some have been enormous. The largest recorded prairie dog town covered some 25,000 square miles. That Texas town was home to perhaps four hundred million prairie dogs. Another prairie dog species, the white-tailed prairie dog, lives in the western mountains. These rodents do not gather in large towns but maintain more scattered burrows.

They have families:

[Towns] are further divided into familial neighborhoods, or coteries. The number of prairie dogs in each town can fluctuate, but will normally amount to 12 individuals per 2.5 acres (1 hectare). These family groupings are made up of one male, one to four females, and their young of up to 2 years of age. Young, male prairie dogs will usually migrate to another colony when they mature, and will seldom start up their own colony.

They socialize and even have social networks:

Jennifer Verdolin, an animal behavior researcher at the federally funded National Evolutionary Synthesis Center, spent hundreds of hours watching prairie dogs interact in Arizona, studying their special “greet kisses.”

Greet kisses are an important part of prairie dog life, and they happen when two individuals approach each other, lock teeth, and kiss. “It can be a sign of who’s in your group and who’s not in your group,” said Verdolin. “If they belong to the same social group, they kiss and part ways. And if they don’t, they break apart and fight.”

Based on kissing patterns, Verdolin sorted the animals into social groups consisting of seven to 15 individuals.

Moreover:

Analyzing behavioral data gave the researchers novel insights about the animals’ social networks. [Amanda Traud, a biomathematics student] found that certain prairie dogs were bridges, connecting otherwise separate groups. Others were hubs, interacting with prairie dogs from many groups.

Prairie dog socialization will take us to prairie dog language in a moment, but for now let us look at how prairie dogs eat, and what the burrows that make up their towns are like. Prairie dogs are herbivores:

Grasses and leafy vegetation make up 98 percent of the diet for black-tailed prairie dogs. They occasionally eat grasshoppers, cutworms, bugs and beetles. Their primarily herbivorous diet provides all of the moisture content that they need—these prairie dogs do not need to drink water.

No need for drinking water? Adaptive on the Great Plains! And here is a description of prairie dog burrows:

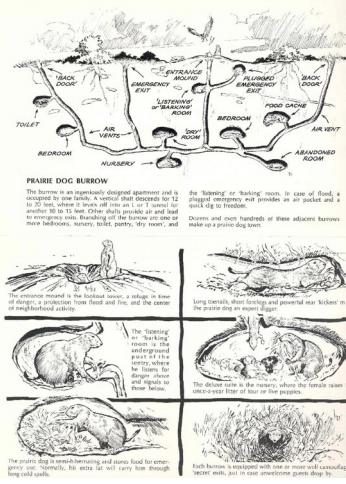

The prairie dog’s burrow is well engineered and efficient home. While burrows may vary, they generally follow a pattern. The entrance is an opening about four or five inches in diameter, centered in a volcano-like mound 8 to 12 inches high. This mound is two six feet in diameter and serves as a lookout tower, a protection from flood and fire, a ready refuge in time of danger, and the neighborhood meeting place. The animal continually maintains its mound, repairing cracks and damage and varying its height and shape. It is normally bare of vegetation because of all the traffic, but surrounding grass is kept low to insure clear visibility at all times. Old timers in West Texas used to predict the weather by checking the varying heights of prairie dog mounds!

Texas readers: Can this be true?

The burrow is dug straight down or at a slight angle for 12 to 20 feet where it then runs horizontally in a ‘T’ or ‘L’ shape for another 10 to 15 feet. Ascending shafts and air vents are dug off this tunnel with one or more terminating in well camouflaged emergency exits 20 to 20 feet from the main entrance. One shaft usually stops just short of the surface with its terminus enlarged. This serves as a catch-all for refuse, loose dirt and trash and, ingeniously, a planned air pocket for trapped dogs in time of flood. From there it’s just quick dig to freedom. Various chambers branch off the burrow and make up the apartment- one or more bedrooms with wall to wall grass carpet, toilet, nursery, dry room, turnaround room (any will do) and pantry. The conning tower of the burrow is the “listening room” or “barking room” located about six feet below the entrance. Here the sentry- usually the adult male- remains on guard whenever the family is “in”

Here is a diagram from the same source. I apologize for the small size, but this was the best available:

(I like the idea of a “barking room”; I could use one at home.) Remarkably, the prairie dog burrow is engineered for passive ventilation:

The burrows can reach 10 m (32 ft) in length, and this size means that diffusion alone is not sufficient to replace used air inside the burrow with fresh air. The way that a prairie dog builds the openings to its burrow, however, helps to harness wind energy from the windy plains and create passive ventilation through the burrow’s tunnels.

As air flows across a surface, a gradient in flow speed forms, where air moves slower the closer it is to the surface. The prairie dog is able to take advantage of this gradient by building a mound with an elevated opening upwind and a mound with a lower opening downwind. Over the elevated opening, wind velocity is faster than it is over the lower opening, creating a local region of low pressure (following Bernoulli’s principle). The result of this difference in pressure between the two openings is one-way air flow through the burrow as air gets sucked into the lower opening and flows out the elevated one. This is the mechanism behind a Venturi tube.

The prairie dog’s diet and its propensity to dig enable it to play its role as an ecosystem engineer:

Prairie dogs are keystone species and an ecosystem engineer and are essential in maintaining grasslands at three levels: a) as ecosystem engineers they have a great impact on the physical, chemical and biological soil properties; through the construction of their burrows they aerate the soil, redistribute nutrients, add organic matter and increase the water infiltration, b) with their foraging and burrowing activities they create unique islands of grassland habitat by maintaining a low, dense turf of forbs [forbs] and grazing-tolerant grasses, contributing to the maintenance of the open grassland habitat and preventing the growth of woody plants, and c) they provide key habitat for many grassland animals, enhance the nutritional quality of forage, which attracts large herbivores to their colonies, and provide important prey for predators; as a component in the food chain ensure the existence of certain carnivores that depend on it, such as the black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes). In addition, their burrows are important refuges for species of amphibians, reptiles, birds and other mammals. The negative impacts of prairie dogs extirpation are, among many others, the regional and local biodiversity loss, the increased seed depredation, and the promotion, establishment and persistence of invasive shrubs.

Or in less academic prose:

Although prairie dogs clip and eat grasses, they also help maintain grassland habitat for cattle. Their landscaping prevents woody shrubs from taking over and can increase the nutritional quality of grass by promoting the growth of young grasses that contain extra protein and are easier to digest. Competition between prairie dogs and cattle is a hotly contested, nuanced issue, and more research is needed to understand the full picture.

And to my ideological point, that there’s more to an ecosystem than trophic cascades:

Keystone engineers are critical drivers of biodiversity throughout ecosystems worldwide. Within the North American Great Plains, the black-tailed prairie dog is an imperiled ecosystem engineer and keystone species with well-documented impacts on the flora and fauna of rangeland systems. However, because this species affects ecosystem structure and function in myriad ways (i.e., as a consumer, a prey resource, and a disturbance vector), it is unclear which effects are most impactful for any given prairie dog associate. We applied structural equation models (SEM) to disentangle direct and indirect effects of prairie dogs on multiple trophic levels (vegetation, arthropods, and birds) in the Thunder Basin National Grassland. Arthropods did not show any direct response to prairie dog occupation, but multiple bird species and vegetation parameters were directly affected. Surprisingly, the direct impact of prairie dogs on colony-associated avifauna (Horned Lark [Eremophila alpestris] and Mountain Plover [Charadrius montanus]) had greater support than a mediated effect via vegetation structure, indicating that prairie dog disturbance may be greater than the sum of its parts in terms of impacts on localized vegetation structure. Overall, our models point to a combination of direct and indirect impacts of prairie dogs on associated vegetation, arthropods, and avifauna. The variation in these impacts highlights the importance of examining the various impacts of keystone engineers, as well as highlighting the diverse ways that black-tailed prairie dogs are critical for the conservation of associated species.

We now come to the question of the range over which the prairie dog exerts these landscape-altering engineering effects. It’s been greatly reduced:

There used to be hundreds of millions of prairie dogs in North America. European settlers traveling through the West wrote about passing through massive prairie dog colonies, some of which extended for miles. But over time, their range has shrunk to less than 5% of its original extent due to a host of pressures, including habitat encroachment by humans.

Here is a map showing today’s range:

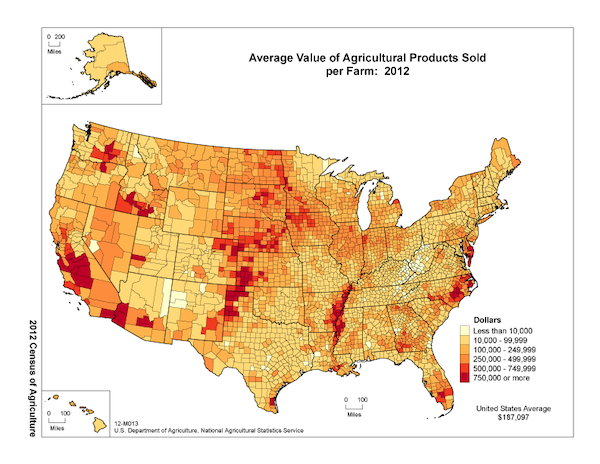

And here is a second map suggestive of human encroachment on the prairie dog habitat:

You will notice that the darkest red portions — the land from which the most profit is extracted — are circumscribed with the prairie dog range. Hence the shooting and poisoning (see also the Appendix).

Has human encroachment on prairie dog habitat posed a moral dilemma of any kind? It could, if we regard “pressures” such as those placed on prairie dogs as problematic for sentient beings. But what is the test for sentience? Some would claim language. Here we come to the work of Con Slobodchikoff, which very unfortunately I must use Wikipedia to summarize:

In the mid-1980s he switched his research efforts to studying the social behavior and communication of prairie dogs. He has been decoding the communication system of alarm calls, and he and his students have found that prairie dogs have a sophisticated communication system that can identify the species of predator and provides descriptive information about the size, shape, and color of the individual predator animal. His research in prairie dog communication has also shown displacement, the ability to communicate about things that are not present. This finding challenges prior theories on animal communication, since only humans had been known to use this linguistic process. In addition, his work with prairie dogs shows they also have different escape behaviors in response to the specific predators identified in the calls of other prairie dogs, even when the predator itself is not visible or scented (ie. based purely on recorded calls). His research with prairie dogs also helps to explain why animals have social behavior. Because these animals form a colony, they form a set of different social groups, which apparently exist for other reasons besides mating and may be a way to take advantage of limited resources.

Through Slobodchikoff’s research, it has been found that prairie dogs also have the ability to construct new words referring to novel objects or animals in their environment, which is called productivity. Prior to the study, only humans had been recognized with the ability of productivity within a communication system.

This article in the New York Times gives a detailed account of Slobodchikoff’s work, from which I will quote the portion on “productivity”:

Why would a prairie dog need such specific information? “My guess is that these descriptions evolved to recognize and remember predators with different appearances and hunting strategies,” Slobodchikoff says. Coyotes, for example, have varying proportions of black, gray, white, red and yellow in their fur. “One coyote might walk into a colony relatively nonchalant,” Slobodchikoff explains. “Some will charge a prairie dog. Others lie down at a burrow, waiting for up to an hour to pounce.” Indeed, some of Slobodchikoff’s studies support the idea that prairie dogs remember individuals. In one experiment, black-tailed prairie dogs — one of the five prairie-dog species in North America — distinguished human trespassers by height and T-shirt color and further produced a signature call for a person who repeatedly fired a 12-gauge shotgun into the ground.

All this evidence, Slobodchikoff insists, elevates prairie-dog alarm calls from the level of mere “communication” into the realm of language.

The counter-argument:

Slobodchikoff’s playback experiments demonstrate that different predator-alarm calls trigger distinct escape responses, but so far he has not been able to link the acoustic variations that ostensibly encode color, shape and so on to any observable behavioral differences. Without such evidence, he cannot rule out the possibility that some of the discrepancies in the alarm calls are an inadvertent byproduct of prairie-dog physiology — an increased sensitivity to a certain color or shape invoking a more forceful rush of air through the vocal tract, for instance — and that the animals do not recognize such differences or use them to their advantage. Perhaps part of what Slobodchikoff deems prairie-dog language is just useless prattle. This is the gaping pitfall of his field: Can we ever know, definitively, that another species is saying what we think it’s saying?

Then again, looking at “the discourse” we humans are emitting…

I don’t have a solution for the destruction of the prairie dog’s range, if a problem it is, though I think that if ranchers style themselves as stewards of the land they should act that way, which probably involves rethinking the notion of property. But I do think that Slobodchikoff starts from the right place;

We're missing the boat on prairie dogs folks. pic.twitter.com/ZJEyXyMrky

— rick evans (@ecosystemmember) July 3, 2021

Prairie dogs are “sentient beings that should be treated with empathy and respect.”

APPENDIX

On prairie dogs and the plague:

Prairie dogs are particularly susceptible to plague. When the bacterium enters a colony, it rapidly turns into an epidemic, or a fast-spreading virus. If this happens, the plague mortality rate is almost 100 percent [source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service].

That high mortality rate and the speed with which plague kills prairie dogs are the principal reasons that humans generally don’t catch plague from them [source: Johnsgard]. Also, North Americans rarely come in close contact with prairie dogs for direct transmission to occur. From 1959 to 1999, only 8 percent of reported plague cases in the United States could be traced back to prairie dog contact [source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service].

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), people usually contract plague from infected fleas. The CDC also reports that ground squirrels and wood rats are the most prevalent plague vectors, or carriers, in the country. Likewise, an examination of plague cases in Colorado from 1947 to 1999 found that you were more likely to catch plague from a domestic cat than a prairie dog [source: Denver Animal Control]. For example, a house cat infected with bubonic plague was recently diagnosed and quarantined in Nebraska.

I confess to having run over one once. A line of them were standing in the freeway watching the sun come up and the light was not good (my excuse).

The burrow construction sounds like one of those cooling towers that have been mentioned here.

loved this.

Groundhogs also don’t have to drink water. Get it from their veggies. Must be a rodent thing. You often see the groundhogs out on wetter days.

Wolves are helpers. They keep the big herbivores moving and not staying in one place so long as to overgraze or overbrowse the vegetation to a near death state in that one place.

https://www.yellowstonepark.com/things-to-do/wildlife/wolf-reintroduction-changes-ecosystem/

If we don’t like the word “trophic cascades”, we can find a friendlier-sounding word for it. Like “habitat helpers”. This article notes that when wolves were re-introduced to Yellowstone, they made the elk start moving again, which allowed the streamside willows and alders and stuff to grow back again, which created enough food for beavers that beavers could come back and make a living again, and start building dams again to access better the alders and willows which the wolves helped to re-grow again.

Perhaps we could call the wolves in this case and this place to be ” keystoning permitters” because their getting the elk moving again gave the willows and alders permission to grow again, which gave the beavers permission to come in and start keystoning again.

( Also, I have read that there are some ranchers who appreciate the habitat-helping properties of prairie dogs and accept them as an eco-significant presence on their ranches).

Wolves. A little-known fact is that wolves are the main predator of coyotes.

Coyotes (magnificent predators in their own right) are what biologists call

a ‘small-s’ species, lots of offspring, while wolves are ‘Big-S’, like humans.

There is another factoid about wolves which belies the common perception

that packs of wolves are led while on the move by an alpha leader.

In fact, the beta wolves lead, followed by old, sick or injured animals,

followed by the rest of the pack. In reality, the ‘leader’ is dead last in formation, with the important role of guarding the rear.

Don’t get me started with the cliche about sled dogs, “Unless you are lead

dog, the view is always the same”. For instance, double leads, or

dogs arranged in a ‘fan’ pattern to spread out the team’s weight when

crossing ice.

woodchuckles and Horne: I also happen to have been doing some research about coyotes (remarkable animals) and wolves. I come to similar conclusions–wolves are not “apex predators” if we assume somehow that individual wolves are evolved only for predation. As you mention, wolf packs include members who have injuries or are old. Barry Lopez remarked on one old female he encountered–her teeth were worn down. His conclusion: She knew how to lead the hunt.

So wolves have teachers.

The research that I did also stressed more than once that wolves are the most social of canines. Wolf fathers stick around (as do coyote fathers, but unlike dog fathers, which take no part in bringing up the pups). The implication is that even though wolves do sometimes travel on their own and spend time on their own, wolves exist mainly in a social structure. A difference that struck me in watching videos of wolves and coyotes is that wolves, when howling, know how to harmonize and use it to good effect. Harmonizing is social.

Does that make them helpers? Well, they seem to have a culture. They have learning. Maybe this complex organization of wolves moving across prairies and tundras should make us think of them as harvesters.

And many Native American tales indicate that wolves have human eyes.

Thanks for your thoughtful reply. I wanted to point out another

useful fact about wolves, as explained by a spokesman for

‘Wolfhaven’ in Washington State. Wolves make poor pets.

The reason is that they constantly mark their territory, which in

this case would be your house. They do this because they want

to keep other wolves away. Since other wolves never come,

the animal thinks this strategy is working, so they will keep on doing it. I could make some glib comparisons to human behavior, in territorial marking, but we are talking about animals,

not humans.

my almost 30 year informal survey of ranchers i know indicates that they have 2 issues that make them dislike prairie dogs: 1. holes, for to break the legs of cattle(plenty of other opportunities for those idiotic blunderers to fracture a leg bone) and…much more importantly, brucellosis. the latter is also why nearly all the cattlemen i have known do not like people keeping buffalo…they also carry brucellosis.

i , on the other hand, have always had a soft spot for them.

long ago, when we’d go to tomball, texas for whatever, and my mom would go to this one friend’s house, i’d get set loose to wander in the woods and fields behind the friend’s house.

there was an enormous prairie dog town back there…maybe twice as big as a football field.

scared the hell out of me the first time i ventured back there and a sentry barked at me.

i went there many times, and watched them…never getting too close(because i was a freak, and after the first encounter, went to the library and read about the various diseases…and i had seen the rattlesnakes)…they were fascinating.

when i learned to drive, that was one of the places i’d go to disappear from the rednecks.

sadly, soon after i started driving, it was decided that that spot was where the new tomball hospital would be built…my first, fumbling attempt at a protest was over this…and i even slit the valve stems of the truck tires of the guy they sent to plug all the holes and gas the whole colony.

so if you ever visit the tomball regional hospital, know that there’s a graveyard underneath it.

there’s still lots of prairie dog towns to the west and north of where i’m at now…especially to the west, where cattle is not as lucrative a venture, due to the desert.

there’s a big one between san angelo and big lake, visible from a little dirt road off of 67.

when i see them around here, in my county, i don’t say anything to anybody…because someone will come along and eradicate them.

neighbor and i have noticed the reappearance of badgers hereabouts…he’s been here since the 70’s and had never seen one…and i wonder what that portends…a lot of the ranchers have aged out or gone out of business, so a lot of the rangeland is “fallow”, now, and is returning to nature. …so maybe the prairie dogs will have an opportunity.

my eyes are always peeled for such things, but i don’t roam around like i once could, so my observations are limited.

reading your above, i kept thinking about how the big red harvester ants…the kind that make trails…perform similar ecosystem services, just at a smaller scale.

there are 4 big ant towns just on our place…literature indicates that they can be 50 feet deep…filled with fungi gardens and aphid cattle…mom hates them, but i have managed to prevent her from attacking them.

The Driver Ants, or Army Ants, of tropical Africa are not so small scale. We had Guinea Fowl in our garden, and when the Ants came through overnight, they left of piles of bones behind.

“Leiningen Versus The Ants” Tells the story of a man’s battle with the kind of ants you’ve experienced. I read it in school as a little boy and never forgotten it.

https://www.bookyards.com/en/book/details/15374/Leiningen-Versus-The-Ants#

I recall that story as well, it’s a great way to introduce kids to literature as pretty much every child has some experience with ants… memorable even after 55 odd years.

Fascinating. Thank you.

I know if I had more time I could find some referrences somewhere on line to “pro-prairie dog ranchers”. Years ago I remember reading about one such rancher in the Stan Steiner book The Vanishing White Man.

I have read about others more recently.

Someone should do a study, if that is even possible, of how much prairie dogs improve cattle-edible prairie plant growth. If that could be quantified, then it could be calculated how much sale-able ” beef growth” the X-amount of p-dog enhanced grass growth made possible above what could have been grown on p-dogless prairie. If the more-money made on the more-beef-grown for all the cattle on the ranch exceeded the money lost by not being able to sell the cattle who broke their legs in a dog hole, then

the greater cash-value of prairie dogs would make its own case. At which any further opposition to p-dogs would be based on pure intangibles like jealouw-rage hatred and death-culture.

And maybe the dog-holes can be a Darwinian selection filter. Cattle which learn to not step in a dog-hole might have calves which can grow up to learn not to step in a dog-hole, and over time the whole herd might evolve an ability to avoid stepping in dog-holes. How often did the buffalo ever break their legs in a dog hole?

One thing for sure, p-dogs counter the slow downward leaching of minerals by bringing mineral-rich subsoil back up to the surface for surface life to bio-activate, bringing those minerals into soil-and-life nutri-cycles.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/7781457-the-vanishing-white-man

Just to add to this, here is a 9-minute video by Con Slobodchikoff talking about the language of prairie dogs-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y1kXCh496U0

He also has his own website at-

https://conslobodchikoff.com/

Why will globalisation be an environmental disaster?

Western companies couldn’t wait to off-shore to low cost China, where they could make higher profits.

Maximising profit is all about reducing costs.

China had coal fired power stations to provide cheap energy.

China had lax regulations reducing environmental and health and safety costs.

China had a low cost of living so employers could pay low wages.

China had low taxes and a minimal welfare state.

China had all the advantages in an open globalised world.

Environmentally friendly measures cost money and reduce profit.

The goal is to maximise profit.

Why do firms move to Mexico and export into the US?

Companies prefer Mexico with its cheap labour, lax health and safety standards, and lack of environmental regulations.

They can expose workers to hazardous chemicals and just pump toxic waste straight out into the environment, without incurring the costs associated in dealing with them in an environmentally friendly way.

https://thoughtmaybe.com/maquilapolis-city-of-factories

Every avenue must be explored to reduce costs.

The lower the costs, the higher the profit.

Western leaders didn’t think through the consequences of maximising profit.

They didn’t realise how China was always going to be the winner in an open, globalised world and how globalisation would be an environmental disaster.

Is this comment at the intended post?

Prairie dogs are one of the species involved in the sixth mass extinction event.

Still got a way to go with that species.

Typo? “This mound is two six feet in diameter”

Overall a very interesting article.

I suspect that we humans are a lot less alone in consciousness than we think.

Problem is just as we often ignore the pain of other humans, acknowledging the consciousness of other beings would mean we couldn’t eat them or pave over their homes quite as cavalierly.

I was pondering theh keystone/ apex predator notion a few weeks ago, after my derisive observation that it appears most ecological models omit man un-kind.

Turns out a lot of folks were on this topic in the mid-twenty teens.

Again and again, I see that we are apart of nature, not a part of nature. Our habits, behaviors, capabilities and actions go so far beyond reproduction and simply living a life.

Another thought, reacting to the point that range improvement should be better quantified to prove in dispassionate black and white numbers the value of retaining prairie dogs on the ranch:

how many animals get put down or fixed by the local veterinarian due to broken legs from badger or prairie dog or ground squirrel holes? I’m thinking the rates may be exaggerated–another western hyperbolic myth and rationalization.

I know of one ‘gopher shooter’ in our valley who actually was very principled and ate (barbq’d) every one she killed.. no wonton waste of game argument to be had there… Have not seen her in years…

Indications are that like me she finally woke up and has put away the guns…

Great article and insights, Lambert. Thank you!

Slightly off-topic, but that map of agricultural output value is really interesting. The hotspots I can identify are Delmarva chicken, NC pork, Florida oranges, Plains beef, and Cali everything (especially almonds?). But what’s along the Mississippi, Snake, and Columbia rivers? And why is central Appalachia so low?

Not sure re the mississippi, but the snake and columbia are dammed for hydropower and ag

One thing that I thought that was a bit odd about that map is that it says the average value of crops “per farm.” There’s nothing inherently wrong with showing that data, but it would be relevant in one way, while “per acre” (or some other fixed unit of area) would be different data and would result in a very different pattern. Many of the “farms” in the Great Plains, which I am assuming includes free-range cattle ranches, would be enormous in area. Small return per acre but huge acreage, making a high return per “farm.” Not that familiar with the area to be able to speculate on your question about Central Appalachia.

Thank you Lambert for a fascinating article. This is a great series that you write on ecosystems. Have you thought of a book collection?

I have tried to post a comment about the prairie dogs which showed up in a dream

I experienced about two weeks before AIG crashed. I have posted it here some

years ago…maybe 2010. (It seems audacious, but I want to say, I am begining

to believe that our collective mind can be recognized as an eco system too and dreams can sometimes reveal its territory.) I am touched by this post and am retyping this dream to demonstrate how a dream in its wholeness can take years to materialize for its meaning to be absorbed.

I am seeing people grouped in clusters. I can only describe the scene as a fancy

international cocktail party where people are being served by liveried waiters.

The perspective of my perception is looking down on the event which is taking place

in what I would describe as a large reception hall.

Abruptly the scene changes. I am now looking at the ground. It is an off white or ecru color of Mediterranean sand. I look up and in front of me, his back to me, is a

nude man. He is as tall as the sky and his body is the color of the sand.

As I watch, suddenly, his knees buckle. I hear my voice or someone’s say ‘oh no!’.

There was no writhing or struggle. His body unraveled in small whirling eddies and I saw it dissolve into the earth/sand leaving no trace of itself. Finally all that I can see are what look like little prairie dogs sitting up on their haunches watching.

_______________________________________________________________

As I awakened I thought…I just saw a God fall. What is it, western civilization, democracy? I didn’t know what to think. I never imagined that Greece itself could be in jeopardy. But the image that made the least sense of all to me was of the little

creatures watching.

Then some years later in the wee morning hours, I awakened realizing that the position of the little creatures standing on their haunches watching most accurately

expressed that of myself as one of the people, only able to watch without a voice.

I have always depended on my own ignorance to know when dreams have given

me something beyond me. I was unfamiliar with prairie dogs and wondered from where it had come. I had maybe seen one once. I love Lambert’s post that enlarges everything.

thanks for the wonderful story

on top of the excellent article

article shows that technology preceded humans

I’m a fan of prairie dogs… actually “Potguts” here – (Uinta Squirrels). The photo was way cute. Potguts aren’t quite that cute, but very smart; known for standing up in a group and watching something like the traffic go by. Pretty sure they are sentient sufficient too. And now we include “social” and even “political” – Prairie Dog architecture indicates politics. Prairie dog mounds are pretty similar to Gobekli Tepi. And (why not?) might be an excellent model for us humans going forward.

Awesome article. Thank you.