Yves here. I’m not sure all direct-to-consumer plays are quite as empty as Jared Holst suggests, but I suspect that is true for national operators. I almost bought a mattress from a Maine company that was set up to sell only in Maine (you pick it up or they ship in the area) And unlike Jared Holst’s empty, erm, lite direct-to-consumer companies, it had a showroom in front and a factory in back! But finding a delivery company to get it to Alabama entailed more brain damage than I was prepared to deal with.

However, not buying from the Maine company was a mistake. The Westin mattress I got instead was complete junk and more costly too. So much for convenience.

By Jared Holst, the author at Brands Mean a Lot, a weekly commentary on the ways branding impacts our lives. Each week, he explores contradictions within the way politics, products, and pop-culture are branded for us, offering insight on what’s really being said. You can follow Jared on Twitter @jarholst. Originally published at Brands Mean a Lot

You Down with DTC, Ya You Know Me

Scroll through Instagram or Facebook on any given day and you’re likely to see one: an advertisement for a direct to consumer (DTC) brand. DTC is a method of sales and supply chain management wherein products are sold directly to consumers by manufacturers–no wholesalers, no retailers, no middlemen–to reduce costs, and thus, prices. Ads from prominent DTC brands are bright and millennial-y—pastels, flat fonts (no use of textures or dimensions), pithy, yet milquetoast copy.

Some of the best known DTC brands include Brooklinen, Casper, and Away. Whereas Sealy and Simmons rely on mattress and furniture stores to sell to consumers, Casper claims to sell its self-produced mattresses directly to consumers, saving them money.

Left: https://www.templaza.com/blog/best-fonts-for-flat-ui-design.html, Right: A brooklinen ad.

1-800-It’s Okay to be Empty

In hyping their ability to offer consumers savings through DTC, most of these brands omit that people producing their products aren’t actually employees. Crack open the sickly sweet shell of many of today’s hottest CPG brands and you’ll find nothing but nothing. Precision social media advertising paired with slick marketing and branding form the shell of something that save for the employees carrying out the aforementioned functions, exists in bits and bytes only. Retail’s hottest trend is nothing more than slapping a digital coat of paint on manufacturing arbitrage and hoping the advertising works.

Great Jones, a company which utilizes the DTC strategy to compete in the cookware arena against the likes of Le Creuset and Cuisinart is no different: A recent Business Insider story about Great Jones, ostensibly about a feud between the two founders and the ensuing fallout, illuminates just how vapid some of these brands truly are.

Turmoil amongst entitled founders, a harmonious startup facade concealing acrimony and backbiting—the best kind of corporate gossip. I can feel my serotonin spiking and pupils dilating in enjoyment. It’s tempting to get lost in the scintillating schadenfreude-y gossip revving my engine (and likely many other’s, given past coverage of stories about the founders of millennial brands Thinx and Away), but don’t get distracted.

Nestled amongst the tidbits regaling tales of founder hubris and entitled egos, sits this morsel:

“A spokesperson for the company said the fourth quarter of 2020 was its best quarter to date.”

The morsel, juicy as ever, can only be unwrapped with this fact, a direct result of the founders behaving so poorly:

On September 3 (2020) the remaining four employees resigned.

As in, the same quarter in which there were no employees was also Great Jones’ best.

The article, camouflaged though it may be, is a beacon revealing just how hollow many of consumer packaged goods’ hottest stars are.

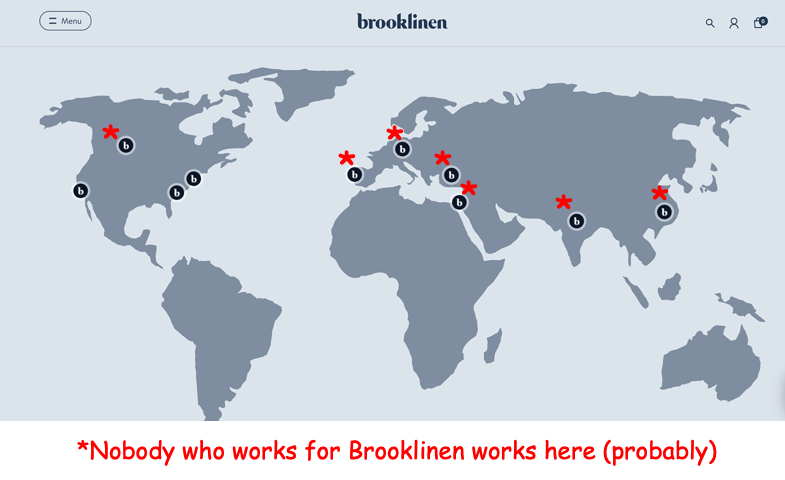

Go to a Ford plant and it’s Ford employees assembling your F-150. Go to a Brooklinen Factory and it’s…some other person producing your sheets, your towels, your robe. A cursory glance at Brooklinen’s Linkedin page lists 114 employees, almost all of which are located in New York City. This, despite professing to have far-flung locations in places like India, Turkey, and China, to name a few.

Source: Brooklinen.com

This means, the same Dutch ovens sold by Great Jones or sheets bearing Brooklinen’s name are sold in many other places, just without appealing finishes and clever branding. The differentiation is literally only skin deep.

Everything Is a Blank Slate

For these companies, and many others in the DTC space, the products are mass-produced in locales which enable hearty worker-compensation arbitrage. The Chinese employees manufacturing Dutch ovens in Tianjin aren’t on Great Jones’ books, they’re on some unnamed manufacturing company’s books. This spares companies from paying anything resembling US wages as well as providing any attendant benefits, be it insurance, retirement contributions, or paid time off (PTO).

Pictured: A Great Jones Dutch Oven

Hollowness aside, the proliferation of the DTC model illustrates the importance of branding and the outsized role it plays in driving purchasing decisions. Used in concert with tracking technology which follows us across the internet, regardless of where and how we use it, and easily accessed cheap labor, branding is remarkably effective as a sole means of revenue generation.

Paradoxically, the events from the Great Jones saga, and what we know about DTC brands in general, also reveal just how pointless branding is. The products these brands represent are nothing more than dull avatars re-skinned to appeal to whatever we project ourselves to be. In the case of Great Jones, a budget conscious, style-forward home chef looking for home goods that don’t just function, but broadcast those qualities to anyone within range.

Both sides of the purchasing equation project themselves onto the other, making an infinite loop of marginal differentiation and superficial appreciation. The supply-side delivers products without material substance to a demand side in search of substance residing not in the product itself, but in its wrapping—physical, digital, or otherwise.

Given this, of whom is the success of these companies a bigger indictment, customer, or brand?

I think direct-to-consumer (DTC) as a marketing strategy needs to be unlinked from a manufacturing company utilizing the practice (as in Yves’ example). An ethical manufacturing company paying a fair wage to its employees, who make the goods, and then ship them to customers who order directly from the company via their website, is DTC but not in the same group as what this author is rightly railing against.

Also, this is stupid:

Just because the marketing aesthetic targets and looks ‘millennial’ does not mean only 30-40 year olds purchased it, nor does it make everyone who purchased the product based on marketing alone ‘superficial’. A business that is nothing more than labor arbitrage and marketing is not some new phenomena that millennials perfected and can be bad on its own without taking vacuous culture war potshots. I assure you this age segment is not the first generation to shop for goods based purely on aesthetic value nor will they be the last.

interesting that writer has branded this as a millennial phenomenon, when in reality much of the products we buy are repackaged crapware, marketed to the various cohorts and lifestyle tribes in a way that confirms their being special and in the know.

Of course, i can see through the bullshit because i wear my redwing boots while shopping DeWalt tools at Lowes.

The difference is that you can examine your boots and tools at your local Lowe’s to assist in determining their quality and ability to suit your purpose. Something not available when purchasing on-line.

With the proliferation of boutique products of extremely high quality only accessible direct from the manufacturer through the internet, some clever people have shifted to niche marketing in the DTC model to take advantage of the dissatisfaction with the price and quality of cheap mass-produced goods.

Unfortunately, a lot of these DTC products are garbage (or mediocre at best), such as the aforementioned dutch ovens. The information asymmetry of what products are actually good versus what products are terribad results in gonzo business for companies with clever marketers.

The even sketchier one are the ones that are just a shiny website wrapper around some sort of dropshipping arrangement.

Just my observation that many give it a good run and long blast of branded advertising and then disappear. As someone pointed out, this didn’t start with the millennials. See the women’s clothing “brands” directly sent to you from China. I don’t know who runs those, but there are myriad complaints. (Those are all over Amazon clothing, btw.) Good luck with a return – you must send it directly back to China.

Yves, I hope you found a bed! That’s another industry I found (when replacing my bed in 2018) that seems to have lots of brand “choices,”but merged down to just a few companies.) “Merged down” probably isn’t the proper term, but you know…

Eventually, this has an end. The End is when the suppliers realize the inherent value in what they’re making and, themselves, sell directly to consumers. This has already occurred with electronic components and chemicals about ~6-7 years ago. It’s Alibaba’s business model, which has partially expanded to Amazon and Ebay causing both those sites to be consumed with cheap, awful, insert-brand-name-here crap that comes out of the same factories.

If there is a silver lining, it makes the difference between “cheap” brands and “real” brands all the more evident. Retail Brand names matter more than ever, now that they face serious competition from fake/generic brands that are eating all their low-end sales and as retailers themselves become desperate for desirable product to keep people physically within their stores. As it turns out consumers have no loyalty, and the big US firms ripping them off have little to say when a Chinese firm comes in and rips them off 20% below them. Either the US firms are wiped out, or in my case with electronics parts, people learn the hard way to vet their components and not buy the cheapest thing.

There’s another angle as well: the more Ebay and Amazon become generic items all set at the same prices, the less reasons people have to shop there. Suppose I want a yellow shoe – I want to select from different styles and sizes. I don’t want the same shoe reposted 20 times over but with different keywords. Consumers want choice, and it’s evident that retails need some sort of police or arbiter to ensure that choice exists.