It appears that even economists are starting to recognize that changes in industry practice that managers and stock touts like to laud as innovation often aren’t beneficial but are extractive. Recall that Paul Volcker deemed the ATM to be the only financial industry innovation he’d ever seen. And as we pointed out in ECONNED:

But opacity, leverage, and moral hazard are not accidental byproducts of otherwise salutary innovations; they are the direct intent of the innovations. No one was at the major capital markets firms was celebrated for creating markets to connect borrowers and savers transparently and with low risk. After all, efficient markets produce minimal profits. They were instead rewarded for making sure no one, the regulators, the press, the community at large, could see and understand what they were doing.

It’s becoming evident that the same principles apply in other fields. This article debunks the idea that the opioid crisis was primarily or even significantly the result of depressed deplorables taking to self-anesthesitizing. Instead, as others have charged, the pill pushers got to be very good at creating addicts.

By David M. Cutler, Otto Eckstein Professor of Applied Economics, Harvard University, and Edward Glaeser, Fred and Eleanor Glimp Professor of Economics, Harvard University. Originally published at VocEU

Over 90,000 Americans died from opioids in the year ending November 2020, bringing the death total since 1999 to over 850,000. This column argues that rather than rising demand for opioids for relief from pain or despair, it is supply-side innovations in the legal and illegal drug markets that have been the main driver of the opioid epidemic. The opioid cycle is a cautionary tale about how technological innovation can go terribly awry, and calls for more collective scepticism about innovations that allegedly cleanse pleasure-inducing drugs of their addictive properties as well as stronger penalties for companies that mislead the public about the risks of their products.

Over 90,000 Americans died from opioids in the year ending November 2020, bringing the death total since 1999 to over 850,000.1 Opioids have killed far less quickly than COVID-19, but the scale of the carnage is similar. Opioid mortality is a significant reason why Americans have stopped living longer lives, as first highlighted by Case and Deaton (2015).

There are two competing perspectives about the cause of the opioid explosion, and they lead to different policy prescriptions. One view emphasises the demand for opioids which has perhaps risen either because of an epidemic of physical pain or economic traumas such as inequality and joblessness. To fix the epidemic then requires addressing those root causes, which could require fundamental reforms of our economic system. The alternative view is that supply-side innovations in the legal and illegal drug markets increased opioid consumption. That possibility leads to calls for tighter restrictions on prescribing and access.

A recent paper of ours (Cutler and Glaeser 2021) finds that while both theories have some validity, the supply-side explanation is far more important (see also Maclean et al. 2021).

Physical pain certainly predicts who got opioids. In the 2009-2010 wave of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, about 60% of people reporting two or more painful conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis or interverterbral disc disorders, said that they had received two or more opioid prescriptions during their 2.5 years on the panel. Only 10% of individuals with no painful conditions and 20% of individuals with one painful condition had received two or more opioid prescriptions. Similarly, the share of a county’s population receiving disability insurance in 1990 or the share with end-stage cancer (Arteaga and Barone 2021) strongly predicts the flow of opioids and opioid-related deaths across place between 1997 and 2010.

But the national opioid epidemic cannot be explained by a secular increase in physical pain. The share of Americans reporting two or more painful conditions increased only slightly between 1999 and 2009. The number of emergency department visits for injuries declined over that period, and so did the share of Americans who reported moderate or severe pain. In our analysis, we estimated that changing levels of reported pain can explain only one-fifth of the increase in opioid use. If we control for pain that is severe enough to interfere with work, we find that only explains 4% of the rise in opioid use.

While opioids are meant to treat physical pain, many social scientists, including Case and Deaton (2020) themselves, have emphasised that economic dislocation can led to despair, which in turn can push people towards opioids. Yet opioid shipments were rising most quickly between 1999 and 2006, and Gallup data shows little change in life satisfaction during those years. Life satisfaction dropped during the Great Recession and then rose again after 2012, but those data don’t correspond to the time series for opioid shipments, which peak in 2010 and then begin a secular decline. Moreover, the flow of opioid shipments between 1999-2010 is uncorrelated with the share of people at the county level who report that they are dissatisfied with their lives. The great shift was not in the level of reported pain or in feelings of despair, but in the willingness of doctors to prescribe opioids for pain.

Humans have had a complex relationship with the poppy plant. The harmful effects of opioids have been known for millenia. Yet there are periodic cycles where opioid use skyrockets and many become addicted. Cycles tend to begin with a new way of delivering opioids that is different enough from pre-existing variants that its makers can claim that it comes without risk. Thus, Freidrich Sertuner, an Austrian chemist, isolated morphine in 1804. It was incorrectly seen as being safer than opium. Serturner himself, and thousands of others – including many Civil War veterans – became addicts. Felix Hoffman, a German chemist working at Bayer, discovered heroin in 1897. The company told its customers that “heroin is completely devoid of the unpleasant and toxic effects of opium derivatives”. This claim also was untrue.

After a first optimistic phase, reality sets in and doctors and pharmacists realise the new formulation is not risk-free. Policy actions are often taken to relock the barn door. The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914 made it illegal to sell certain opiates, even with a prescription. Yet even when doctors refuse to prescribe morphine and heroin to addicts, they leave behind a stock of addicted consumers, many of whom turn to illegal suppliers. The ‘French Connection’ was infamous in the 1970s, though it was not unique.

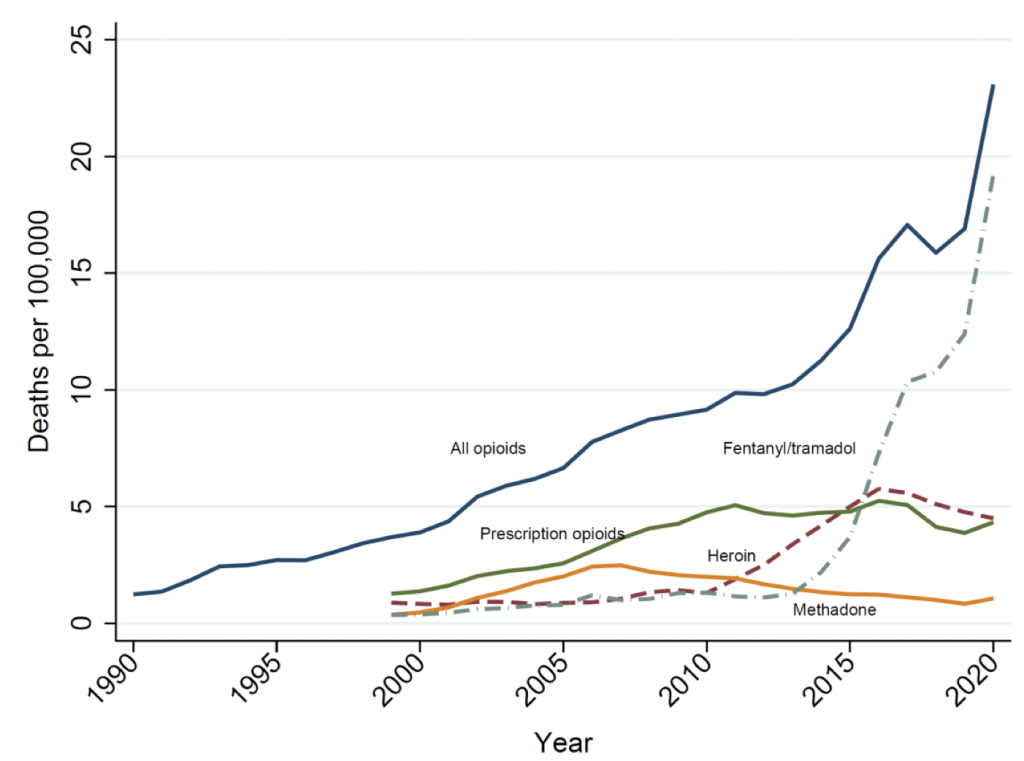

The current wave of opioid deaths is much like the past. It began when Purdue Pharma began heavily marketing OxyContin in 1996 (Figure 1). The ‘contin’ system delayed the release of the drug into the body, which supposedly provided long-term pain relief and simultaneously alleviated the risk of addiction. Purdue had long been a marketing powerhouse, and it promoted OxyContin’s supposed safety relentlessly. The company widely broadcast a 1980 letter to the New England Journal of Medicine, which was not peer reviewed and involved only inpatients, claimed that among “11,882 patients who received at least one narcotic preparation, there were only four cases of reasonably well documented addition in patients who had no history of addiction” (Porter and Jick 1990). Their sales pitch fell on fertile soil, in part because of a growing medical movement that focused on alleviating pain rather than just on treating illness.

It did not take long for the first hints of failure to emerge. By the early 2000s, increased opioid-related deaths were noted in Maine, West Virginia, and Kentucky (Tough 2001), all areas with lots of manual labour and thus high rates of pre-existing pain. Deaths rose apace with opioid prescriptions throughout the 2000s.

Figure 1 Trends in age-adjusted drug deaths and opioid deaths, 1990-2020

Source: Data through 2018 are from Cutler and Glaeser (2021). Data for 2019 are extrapolated from growth rates from CDC. Data for 2020 are extrapolated from deaths in the first 11 months of 2020 relative to 2019.

The rising death toll eventually generated a regulatory response. Under pressure, Purdue Pharma produced an abuse-deterrent form of OxyContin in 2010 that made crushing and injecting the drug harder. As law enforcement cracked down on pill mills and doctors again became skittish about prescribing opioids, users turned to illegal drug markets. Entrepreneurs were more than ready to supply customers. Cicero and Ellis (2015) found that one-third of opioid users switched to other drugs immediately after the reformulation of OxyContin; the majority of those who specified a preferred alternative named heroin. Similarly, Evans et al. (2019) found no impact of the reformulation of OxyContin on overall drug-related mortality. An increase in the number of deaths from illegal substances offset the decrease in the number of deaths from prescription opioids. Quinones (2015) describes the highly efficient distribution network for heroin. Dealers used a system of drivers to carry Mexican-produced heroin right to one’s doorstep.

Yet heroin was not the ultimate endpoint. Fentanyl is more potent still and cheaper to produce; it does not require access to poppy plants. The precursor chemicals to fentanyl often come from China, though Mexico remains an important assembly and distribution point. Because the potency of fentanyl varies greatly from batch to batch, it is particularly deadly. Since 2014, fentanyl has become the most commonly implicated opioid in overdoses.

With the realisation yet again that opioids are not benign, the flow of new opioid prescriptions has fallen dramatically. It shows every sign of remaining low. But there is a large stock of existing users, many of whom will continue to use opioids illegally. Unfortunately, the pandemic made life worse for addicts: social isolation made escape into oblivion particularly attractive; pandemic-induced changes in suppliers made potency more variable; and reduced access to addiction treatment made supervised withdrawal harder. Hopefully, economic normalcy will reduce opioid mortality. That said, addiction treatment will need to be massively scaled up to safely reduce addiction (Lopez 2017).

The opioid cycle is a cautionary tale about how technological innovation can go terribly awry. If we want to reduce the risk of the cycle repeating anytime soon, we will need to change our approach to technology. This will require more collective scepticism about innovations that allegedly cleanse pleasure-inducing drugs of their addictive properties. In addition, we will need stronger penalties for companies that mislead the public about the risks of their products. To be sure, Purdue Pharma will likely cough up billions for its handling of OxyContin. But the Sackler family became fabulously wealthy from opioids, and it is unclear how much the family will be penalised (Lopez 2019). Health is too valuable and addiction too consequential to leave life and death decisions to the market alone.

Authors’ note: Cutler is involved in the multi-district litigation regarding opioids as an expert witness to the plaintiff counties suing opioid manufacturers, distributors, and dispensers.

See original post for references

Re Fentanyl. Unfortunately I did a study that helped this along at the start of my health economics career.

Back then I got a cool trip from London to Ontario (although in February and I learnt what real cold was) to interview 12ish specialists (mostly in palliative care) about pain management. What immediately struck me was that most were British expats who regarded the UK as barbaric and why they left to live in a country that gave patients “all the pain meds they wanted”.

The Fentanyl patch was lauded. Of course naive me thought I was doing good in showing that similar outcomes (compared to traditional morphine/diamorphine) were possible at cheaper total cost (since the additional cost of Fentanyl was offset by much lower prescriptions for constipation and even when the total cost went up, other convenience factors etc made Fentanyl seem highly cost-effective to a body like the NHS.) That was a Canadian province in 1998 but I’m willing to bet similar arguments were being made across the border about the “convenience” of the patch. All gain, no more pain. I soon came to hate the fact my CV had that paper as one of my first publications and it prompted my move into the public sector. Sadly that came with its own set of issues…..

And as a postscript, I got tangled up in the most recent “cycle” of a wonder drug that deals with pain (and anxiety) – pregabalin. Sadly, and I believe with the very different statistics I used in my post-doctoral work I could spot this, drugs like Fentanyl and Pregabalin are not “simply bad for everyone”. They are meds that have a bimodal distribution in their effects. One group of people will swear by them and genuinely not become addicted or develop tolerance. Another will end up in deep trouble. A mental health professional told me a few years ago that the majority of people detained under the Mental Health Act at the inpatient unit next door were there for pregabalin offences and it had become the street drug of choice. It got reclassified by the govt soon after. Yet the medics still can’t predict which of the two groups you’re likely to fall into – it’s not as simple as “this patient has an addictive personality” or “this patient abused benzos”. It’s all pretty depressing.

You can get high on pregabalin? It just makes me fall asleep and comes with bad side effects. Either effects differ in people or people are really psychically hurting, if they’re abusing pregabalin.

Oh my yes. Way too few docs realise that the recommended starting dose is wayyyyy too high for a bunch of people. First day I took it I couldn’t work, lying on my bed thinking “is this what heroin addicts feel?” It was a Sydney psychiatrist who initiated me on it partly because (at that point anyway) it was NOT licensed for generalised anxiety disorder in Australia. It was being used “off-label” for anxiety pretty widely “because the Europeans and North Americans were doing so and we’ll follow in due course”. It was “officially” licensed only for chronic pain, which ironically it helped me with – years of economy class flights from Sydney to London/LA/etc (universities don’t reimburse biz class) had given me a slipped disc so when I got sloppy with my exercises and Pilates it was actually helpful there.

I pretty quickly stopped getting high but was clearly developing tolerance as my dosage had to keep going up. When I returned to the UK I, and my docs here, were horrified and thus began a truly horrible year of getting me off the drug. Ironically benzodiazepines – the “big boogeymen” – cause no addiction or tolerance in me. I am trusted to take time off mine, muck around with my dose, and generally not allow my body to get accustomed to it and keep it for bad periods.

My mum’s cousin in Dublin gave up on Pregabalin after one day (prescribed for pain) when she got high as a kite and felt very distressed. I’d warned her that her starting dose sounded way too high – her (private) doctor had not even done the whole “halve the dose for an older person” thing. But because I’m PhD (med stats) not medical doc, I find that relatives listen to me when it suits them…..*sigh*

The irony of the “pregablin abuse” is that they’re not exactly chasing highs like with a bunch of traditional opioids….but that it just seems to turn off all your “worry circuits”, but most especially if taken with other meds – some of which are perfectly legit anti-depressants and it’s like a permanent mild dopamine high where you are lucid, perfectly able to work and function, but you’re on a long-term road to disaster. I submitted an official “adverse drug reaction” report under the UK Yellow Card scheme for pregabalin once I joined the dots and noticed its effects had been amplified by my particular antidepressant.

re “psychically hurting” – maybe but maybe not. This is the weird thing. The relationship between mental health and response to it is very unclear. The effects definitely differ among people and as of this point they have no idea why.

Weird! Different people = different effects. I’m on pregabalin for a chronic lower back problem probably caused by stress. I’ve never gotten high, and never had anxiety reduction. I hate the drug and I’m trying to slowly reduce out of it. It makes me brain fogged and I need 10 hours sleep a day or I have miserable muscle aches the next day and feel like I got run over by a truck. I’m tapering off (you must know the routine) and hope to just keep it for flair-ups.

All I can say is it and gabapentin have some brutal side-effects that doctors and patients have to watch for. The upshot is that we need a saner society with less stress…

Stay better and don’t let the academic/medical rat-race grind you down to misery.

Yes it works wonders for lower back pain – my Sydney record “officially” had that as the reason for using it so I wouldn’t get my psychiatrist into trouble and had the benefit of actually being (at least partly) true.

Yes, it and its “little brother – Gabapentin” are very very troublesome meds in a lot of people. After Pregabalin and Gabapentin got reclassified to be “Class C” drugs in UK (like benzos) I kept looking at an open access site on total prescriptions per drug in every practice your your “CCG” (often around 20ish General Practices in your local area). I saw the prescriptions for the two drop off a cliff. Except at one Practice. Since I grew up in this city I knew the characteristics of that Practice – lots of male patients on disability benefits who did awful physical work down the mines 40+ years ago when we had a mining industry and who now presumably all have back issues. The GPs have clearly successfully managed to keep these patients on the meds, which is interesting.

re the rat-race – haha way too late for that, I exited a few years ago…..do a lot of family caring stuff at the moment.

Human Leucocyte Antigen B6 (HLAB8) is a fairly strong predictor of alcohol addiction. It would be great, as you say, to have a good predictor of opioid addiction.

Great bit of into there, thanks. Indeed the “predictors of success” plagued my professional career in more than one area. For 8 years my “big boss” was Professor Paul Dieppe. He literally wrote the rheumatology textbook, blew the whistle on Vioxx and has spent his later years trying to understand why some people, despite good pre-op data, exhibit terrible outcomes following joint replacement (my mum is one such patient).

This “cycle” and bimodal distribution of pregabalin is rather interesting. Did the pharmaceuticals purposely set the recommended starting dose high so that patients become dependent on it and then persist to take the drugs when the addiction withdrawal kicks in? Please tell me more.

I have neuropathic pain and neuropathy-like sensations. For neuropathic pain, doctors hand out the gabapentinoids (pregabalin and gabapentin) like candy. The greedy doctors even pushed benzodiazepines and SSRIs on me even though no sane person would ever conclude I have anxiety or depression. The good doctors and I know that my main problem is not necessarily pain because I experience mild amounts of pain in terms of intensity. The pain is still horrifying in terms of duration. Thus, my doctors agreed with me that the risk posed by gabapentinoids is too great for me.

As for the risk posed to other readers here, please try to exhaust all alternatives before taking gabapentinoids (or even worse, drugs that act on mu opiod receptors). Try lifestyle changes, chiropractors, physical therapy, massage therapy, avoiding whatever triggers your neuropathy. Perhaps even try traditional Chinese medicine, even though I just ranted about it two days ago.

You’re welcome. Dosage reflects current flawed models of statistics where “everyone is interchangeable” and the central limit theorem is invoked. It’s far from clear the CLT can be invoked when you have 2+ fundamentally different “types” of patient and your outcome is discrete rather than continuous. So I can’t ascribe motives.

One point regarding “seemingly ridiculous” types of drugs prescribed for pain. Look up amitriptyline. Old school antidepressant but, like aspirin, has been found to be beneficial in loads of other contexts it was never designed for. It is used in pain management. Ironically that’s how I discovered it. 50mg (wayyyyy below the minimum dose for use as an antidepressant) can give amazing benefit for certain pain. Also good for insomnia and unlike “normal” drugs for that it is not addictive. I used it for years.

I did not expect to see Fentanyl in my sedation cocktail for my recent colonoscopy

Fentanyl was invented around 1960 as an anaesthetic. It was quickly established that it worked incredibly well but the dose-response relationship can be unpredictable so it remained as “something only used by anaesthetists in medical procedures” for yonks and I’m not exactly surprised that it might still be used that way today – it’s perfectly fine if used by an expert. The patch was an “innovation” that helped regulate how much and how quickly it got into your system with a “smaller need for medical supervision” – hence why it became both “useful to cancer patients in controlling their pain relief at home” and then “something addicts could abuse without the extremely high risk of killing themselves”.

Then of course innovation caused it to be re-engineered as a pill or some other form to give the quicker “hit” and the rest is history…..

I had it in a recent gastroscopy for stomach ulcers. It knocks you out fast. No high here. Again your mileage may vary. My spousal unit had it for a recent colonscopy and got totally high. Manoeuvring his very happy inebriated self home via metro and bus was challenging! Everything distracted him and made him happy. Getting him to think “must go home now” was impossible. I guess after a colonoscopy, he deserved something happy…;^) They are not pleasant.

Look at the class character of the majority of the fatal overdose victims (including those addicted by prescription). This helps to understand the eugenic ideology of the elites and policy makers who watched and profited from this slaughter over the past 30 years.

A contrary anecdote:

A friend of my brother had terminal cancer. He died in agony because his doctor had been hounded by the DEA about pain prescriptions and was afraid to prescribe an adequate dose. But that’s contrary to even the “cruel” Old Testament:

Give intoxicating drink to one who is perishing,

And wine to one whose life is bitter.

Let him drink and forget his poverty,

And remember his trouble no more.

Open your mouth for the people who cannot speak,

For the rights of all the unfortunate.

Open your mouth, judge righteously,

And defend the rights of the poor and needy. Proverbs 31:6-9

Note also the connection between poverty, misery, and the need for psychological escape. Note also that per Deuteronomy 15:4-5, poverty is a result of disobedience to God, at least with regard to economic justice, and is not inevitable, especially to a large extent.

So beware of treating a mere symptom and in the process adding cruelty to economic injustice.

Disabling pain is a reality. The fads in treatments for what one must provide subjective ratings from 1 to 10 before and after prescriptions are not easy to interpret. Too bad i don’t have a test metering strip similar to what is provided on the higher cost Duracell batteries.

Marijuana does have medicinal effects. “Yeah it hurts, but I don’t care as much?” It appears to me that cannabis is complex and there is a rational basis for seeking a strain more effective with pain.

physical addiction to marijuana is not a side effect.

BINGO. And this is why I think a fairly large portion of medicine (including the categorisation of pain) is wrong and bordering on criminal and indeed ties into the point made above by user saywhat?

Giving a “pain score” on a scale of 1 to 10 sounds intuitive. It’s also absolutely family-blogging terrible and easily manipulable. Did you know that a Chinese person with traditional (“old fashioned”) Mandarin beliefs won’t give you a 4 because that has connotations with death? That some people deliberately just use the endpoints? That others never use the endpoints? Humans are truly terrible at numerical scales and the mathematical psychologists (going back to Marley and R Duncan Luce) in the 1960s showed this. But there was never a “Nobel” in THEIR field so various economists got to rediscover this stuff and get rewarded.

Pain scores must be cardinal in a mathematical sense to undertake all the analyses we put them through. They’re demonstrably not. Just go peruse a few review articles by the two authors mentioned for evidence. This is just ONE reason why “discrete choice modelling” took off in giving numbers to things that ACTUALLY mean something (namely, how often would you say/do this in 100 parallel universes)?

This ties in with the “drug debate” above……I suspect that rather than two groups, one responding “appropriately” to a med 100% of the time and the other responding 0%, we have a sliding scale with two peaks. This requires different statistics – which are published and underpin an Economics “Nobel” as well as numerous other mathematical/statistical results. However, we like our answers nice and simple. Reality probably isn’t described properly by discrete choice models either but at least we’re relaxing stupid assumptions and not assuming that when Mrs Smith says “4” she literally means her pain has halved from pre-treatment when she said “8”.

As horrendous as all of this is, it’s only half the picture. Deceptive marketing and bribing doctors to prescribe more opioids are demand side influences. But there were also considerable supply side corruptions that helped enable the opioid epidemic.

Most opioid drugs are synthesized from the organic compounds found in opium poppies. Nowadays we use high yielding genetically modified opium poppies, and the largest farmer of these poppies is a company called Tasmanian Alkaloids. Tasmanian Alkaloids was until 2016 a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, along with its sister company Noramco, which refines these poppies into opioid active pharmaceutical ingredients (oxycodone, hydrocodone, ect). Noramco was the largest U.S. producer of these ingredients, supplying drug companies like Purdue Pharma, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Mallinckrodt, Endo International and Allergan. And the opium poppy that Tasmanian Alkaloids modified was able to evade rules limiting how much opioid raw material could be imported into the U.S. According to a very interesting article about this part of the opioid supply chain:

“In 1994, chemists tweaked the opium poppy so that the plant produced higher yields of thebaine, a chemical precursor for making oxycodone. More importantly, this transformation enabled United States manufacturers to evade a long-standing regulatory cap. Historian William B. McAllister, author of Drug Diplomacy in the Twentieth Century, suggests that thebaine may be a case of “regulatory entrepreneurship,” where pharmaceutical companies attempt to figure out ways of getting around international drug controls to gain market share. Tasmanian Alkaloids, a pharmaceutical company based in Australia, followed by other firms, was able to ship thebaine despite the formal agreements because Drug Enforcement Administration rules governed the importation of morphine but, by 2000, clearly did not apply to thebaine. This regulatory regime was an unheralded but necessary precondition for the explosive growth of opioid production and oversupply in the last 25 years.”

So the main poppy grower and refiner found a way around rules that restrict how much opium the U.S. imports, and without this the drug companies would not have been able to manufacture so many opioid drugs.

Manufactured drugs are distributed to U.S. pharmacies by an oligopoly. McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health together distribute over 90% of U.S. drugs to pharmacies. These companies are by law supposed to report suspicious orders of controlled substances to the DEA. Despite this distributors have flooded the country with 76 billion opioid pills between 2006 through 2012. 76 billion pills amounts to approximately 33 opiate pills per year for every man woman and child in the United States during the 7 year time period covered in this article. And that’s only oxycodone and hydrocodone – it doesn’t include the various types of fentanyl. Maybe 33 opiate pills per year, per American, for 7 years didn’t sound that suspicious to them.

These innovations to evade regulations occurred at almost every stage of this products lifecycle. As we can now see the consequences are disastrous.

Thank you Terry Flynn. Yes, fentanyl has been used forever for anesthesia. I’m grateful for your knowledge. Also, Lincoln, I had no idea of the poppy issue.

I’m normally not libertarian leaning, but honestly? If you’re going to be addicted, you’re going to be addicted. I see many differing statistics regarding how many people have died from overdoses in the last 20 years, whether they involved alcohol and/or other drugs. (The CDC states that in 20 years, 842,000 people have died of overdoses. And my research shows most of these did not involve scrips.) I’ll place bets that the stats for guns and alcohol deaths far outweigh the overdose panic. There are now questions about health issues with cannabis. Hmm. That sounds like someone should have done some research. The strains are very strong.

As someone mentioned, all bodies react and process chemicals differently. Neurontin? For me, it’s like being wrapped in cotton while dealing with massive migraines.

One is unable to control intractable pain without being treated as a criminal, but one can destroy their liver with alcohol and nsaids legally and smoke ciggies till they drop dead. There are people in serious intractable pain and they are adults. Further, said pain drugs are still being manufactured. (What’s the black market look like? Do we want people to head to the streets?) I want the government out of my life so I can live as normally as possible and the “experts” in the US who are making policy (behind closed doors) out of the rehabilitation business, which is an enormous conflict of interest. Follow the money, as they say. (These opinions are strictly my own as a cranky disabled old fart that wants as normal life as possible and doesn’t want to be in a wheelchair, just yet, or at all…)

https://www.cdc.gov/opioids/data/index.html