Yves here. We’re using the topic of globalization to illustrate an old saw about economists. When a young economist presents an intriguing and important finding to an older colleague, the greybeard remarks, “So it works in practice. But does it work in theory?”

This post provides a theoretical justification for a pattern observed with increased globalization: a rise in profit share of GDP, in the last 15 years nearly double a level that Warren Buffett deemed unsustainably high, and a corresponding fall in labor share.

By Nuno Limão, Professor in the Economics Department, University of Maryland; Research Fellow at NBER and Kiel Institute for the World Economy and Yang Xu, Assistant Professor, School of Economics & Wang Yanan Institute of Studies in Economics, Xiamen University. Originally published at VoxEU

Production is increasingly specialised, with firms concentrating workers on certain tasks that take advantage of outsourced intermediate inputs (Ariu et al. 2019, Timmer et al. 2019). Intermediates are an increasingly large fraction of international trade (Johnson and Noguera 2011, 2017); access to them can increase firm productivity (Amiti and Konings 2007) and it may also lower labour shares in manufacturing (Elsby et al. 2013). Labour share declines have also been attributed to increasing profits due to higher concentration (Barkai 2020) and a shift of production towards larger and less labour-intensive firms (Autor et al. 2020).

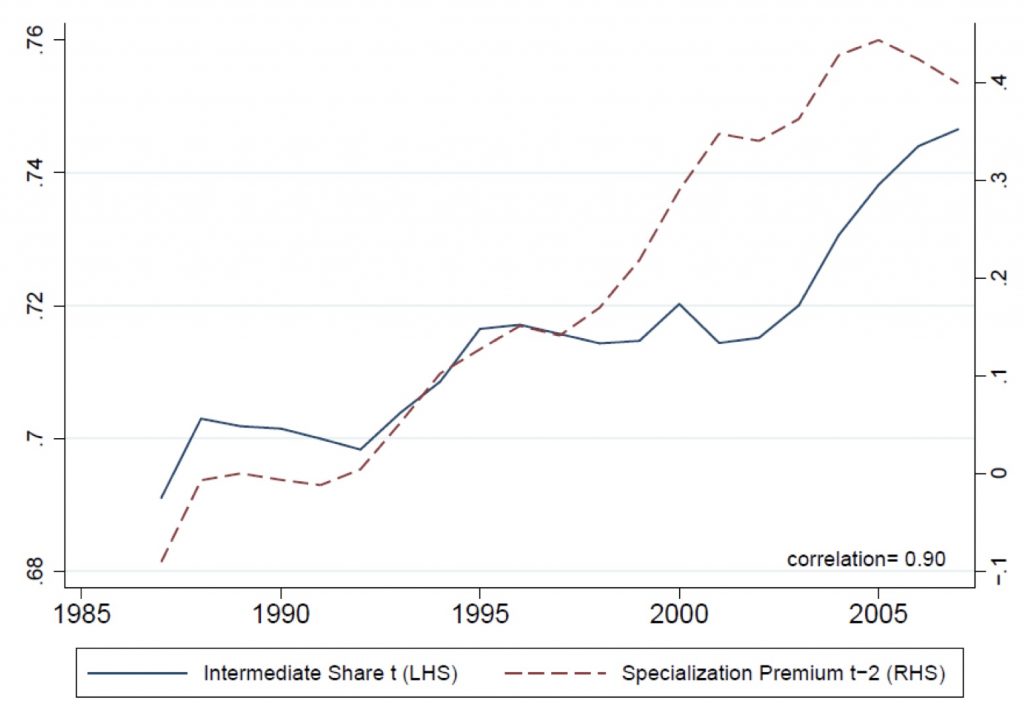

In a recent paper (Limão and Xu 2021), we study the relationship between globalisation and specialisation, and its implications for the labour share and income. We define specialisation as the share of intermediates in variable production costs. Figure 1 shows specialisation within manufacturing industries in the US increased about five percentage points between 1987 and 2007, about half of it since China’s WTO entry.

Figure 1 Intermediate cost share and specialisation premium, 1987-2007

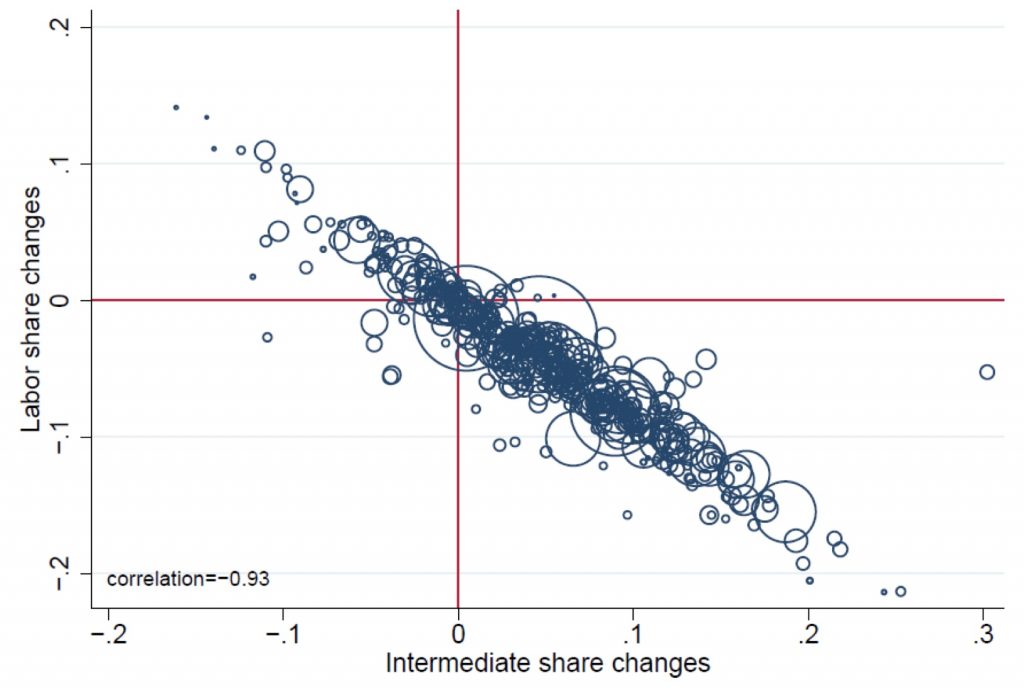

Figure 2 shows that the industries with the largest increases in intermediate cost shares over this 20-year period are also the ones with the largest labour share declines, which suggests intermediates are replacing labour (as opposed to capital or energy).

Figure 2 Intermediate and labour cost shares, 1987-2007 change

We develop a framework where the relationships above arise from firms adopting intermediate-intensive technologies as markets expand. A key determinant of adoption is the relative price of labour to intermediates, which captures the trade-off between in-house production and outsourcing intermediates from other firms. In Figure 1 we see that this relative factor price increased at an annual rate of 2.5% and that it is strongly positively correlated with production specialisation. This relative price captures the cost savings from intermediates relative to labour so we call it the specialisation premium and find it is positively correlated with trade openness.

Motivated by these and related findings, we model endogenous firm specialisation. Firms can lower marginal costs by adopting higher intermediate-to-labour intensive technologies by paying a fixed cost. The resulting economy of scale at the firm level captures one aspect of Smith’s (1776) specialisation argument: when markets are larger firms have an incentive to specialise their labour into a subset of tasks where they are most productive.

We also incorporate a feedback effect that generates an endogenous input-output multiplier. The increase in productivity from specialisation lowers prices and these products can also be used as intermediates. Thus the initial market expansion lowers the relative price of intermediates, which leads to additional specialisation and demand for intermediates.

Similar to other models with input-output linkages, the input-output multiplier reflects the aggregate intermediate cost share, but a key difference in our framework is that this share is not constant because of endogenous specialisation. We show endogenous specialisation has interesting and important implications. Increases in market size, for example due to lower trade costs, generate:

- larger real income gains relative to exogenous specialisation;

- an increase in the aggregate variable cost share for intermediates and a decrease for labour;

- an increase in concentration of profits and sales, as the most intermediate-intensive firms are the ones that benefit the most from the reduction in the relative price of intermediates.

A calibration of the model to US manufacturing in 1987–2007 illustrates the importance of trade and technology shocks in explaining several facts, including the relative increase in intermediates to labour share. We carry out two policy experiments based on our calibration. First, an industrial policy (e.g. a tax/subsidy) that induces all firms to specialise would have increased real income, so the equilibrium is inefficient (firms don’t internalise the externality of their adoption decision on others). That income increase is significant if the policy was implemented in 1987 but negligible in 2007 since, by the latter period, trade and technical change had induced sufficient specialisation. Second, we compute the impact of an increase in trade costs of 16 log points, similar to the recent trade war, and show it increases the labour share but reduces market size and real income substantially – almost half way to the predicted effect of the US shutting all trade.

See original post for references

I think that what the authors call “profit” is more like what the classical economists called economic rent — resulting from market power, not tangible capital investment to employ labor to produce exports and other products.

Lack of the classical distinction between value, price and rent (vs. profit) is a common feature of this post-classical approach.

This sounds like a less-than-honest analysis of the problem that competition causes in a technological world. It causes specialization (usu. automation) that replaces labor but still maintains adequate production so supply is no problem. Quality is improved. Prices come down. Etc. So, strangely, I just saw one of the Fed Vice Chm. on a CSPAN program talking about QE and interest rates… If I understood him correctly he is not worried about a lack of jobs (labor) causing insufficient supply. He sounded satisfied that supply is no problem these days. But he didn’t have a 10-foot pole to poke the fact that the Fed has a mandate for full employment in a world of automation. I’d really like to hear that discussion. Because Demand is being precluded by both unemployment, and soon by a lower birth rate. I’m thinking there really is only one answer – work programs. Why won’t anybody say so?

“I’m thinking there really is only one answer – work programs. Why won’t anybody say so?”

There’s another answer: Shorter work weeks. Spread the reduced labor hours across more people to better share the load.

Absolutely, isn’t that what Keynes forecast back in the 1930s. By the 21st century productivity would have doubled and we would be working a 20 hour work week. And then in the 1960s the feminists declared that if women shared equally in work nobody would have to work more than a few hours a week. More time for family, vacations and avocations, etc.

I don’t think it’s automation – it looks like a straight outsourcing story. But I agree that the framing of the article seems designed to obscure that. NAFTA was 1993 and 2000 was when China joined WTO – fits perfectly with the chart. As does the fact that increased “intermediates” is associated with lower labor cost shares.

Part of the problem here is that, due to virtually all economic data being collected at the national level while virtually all mfg, esp the firms that decide what gets made where, is/are global/multinational, we don’t really have good schemes for collecting data throughout the whole production chain. (To do so would require gov’ts to demand a lot more data from companies than they do, and to ask a lot harder questions than they do now, esp about things like transfer pricing.) So economists, even the few good ones, have to try to develop indirect work arounds to figure out what is really going on.

I agree with questioning the article not looking closely enough at outsourcing vs automation. Aaron Benanav’s Automation and the Future of Work makes a strong argument for the weight of the former. And, yes, thumbs up for shorter work weeks.

as does it fit perfectly with thomas pikettys graph, inequality was rising before hand for sure, but in 1993 it took off like a rocket shooting skywards.

then went up again mysteriously around the time of the implementation of bill clintons W.T.O. , then rose again when china entered thanks to bill clintons free trade with china.

https://radioopensource.org/capital-in-10-graphs/

the charts in most cases suspecially mirrors the implementations of bill clintons free trade.

and note, the explosions of billionaires in the world just coincided with all of that free trade.

those people will never share a penny with anyone no matter how efficient things get, and remember, under free trade efficiency means the fodder are feed just enough to be malnurished, not starving to death, they make just enough to stay alive.

there is a 100% correlation that free trade is fascism

In 1996 there were 423 billionaires

was it free trade that created all of these billionaires, you bet it

was. In 1996 there were 423 billionaires, In 2019 that number rose to

2,153.

when fascism came to america, its was sold as free trade spreads

democracy, and eradicates poverty

Billionaires constitute just 0.00003 percent of the world population,

but they currently own the equivalent of 12 percent of the GWP (gross

world product) and a much larger percentage of the total wealth of the

world.

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2020/12/do-billionaires-destroy-democracy-and-capitalism.html

in 1983 there were only 15 billionaires in the u.s.a., under bill clintons free trade, billionaires have ballooned into more than 615, and under free trade, this is happening globally

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/04/01/magazine/costs-secretive-wealth-defense-industry-shell-companies-offshore-tax-havens-empty-luxury-condos/

thomas frank is usually good, he was here,

https://radioopensource.org/neoliberalism-and-postcapitalism/

Is ‘factorless income’ the new term for economic rent?

http://mattrognlie.com/kn_comment_rognlie.pdf

Figure 5 of Rognlie’s paper I linked to above points to two ‘unambiguous trends – the rise in housing income and the rise in depreciation of intellectual property products‘.

“Labor share declines have also been attributed to increasing profits due to higher concentration” == monopoly and monopsony rents

“A key determinant of adoption is the relative price of labor to intermediates, which captures the trade-off between in-house production and outsourcing intermediates from other firms.” == labor arbitrage

“economy of scale at the firm level” … “incentive to specialize their labor into a subset of tasks where they are most productive” — “economy of scale” == economic magic incantation and blessings to avoid a closer look at the nature of the so-called specialization of labor wedged into Smith’s pin factory.

The final paragraph of this post is … fantastic. I seriously doubt a “calibration of the model to US manufacturing in 1987–2007” is parsimonious in explaining the growth in labor arbitrage fostered by globalization. The very idea of a tax/subsidy to somehow encourage “firms to specialize” == expand their labor arbitrage, is quite beyond the pale.

Look likeGreed by union busting. Union busting by exporting jobs.

And Ignoring that Customers are also Workers.

The SA Rand used to be at parity with the US dollar. Now there are 10 to 15 Rand to the dollar.

What has the done for SA peoples’ retirement?

A similar recipe also describes the value of the UK Pound.

From the article, it seems like they are not counting labour input into the “intermediates”? So, if a firm fires 10 workers who used to make subcomponent X, and then buys subcomponent X from another firm that employs 10 people to make it, then the article would count this as a reduction in labour cost share.

I can’t find the underlying NBEr article itself, so I cannot verify this.

If that reading is correct, then the article is mostly just describing outsourcing to countries with low wages?

It would help (a layman like me) if they defined what an “intermediate” is.