Yves here. Hubert weighs in after yet another dodgy Uber earnings report.

By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines). Horan has no financial links with any urban car service industry competitors, investors or regulators, or any firms that work on behalf of industry participants

On August 4th, Uber announced its second quarter financial results. The first part of this midyear review was published last week as Part Twenty-Five. It examined the data in Didi’s recent IPO, laid out the strong similarities between the terrible economics of Didi and the terrible economics of Uber, and discussed the increasingly divergent Chinese and American government responses to tech companies that have demanded total freedom from legal oversight despite their inability to produce benefits for the rest of society. It also pointed out short-term financial linkages, such as Softbank selling off large portions of its Uber shareholding in order to cover losses from the collapse in Didi’s share price. [A1]

Part Twenty-Six, following the format of past reviews, summarizes the highlights of newly published Uber financial results, and how those results were reported in the business press.

Part Twenty-Seven, to be published tomorrow, examines two major examples of pro-Uber propaganda published in the last months. Understanding Uber’s propaganda approaches is critical to understanding how a company with eleven years of awful financial performance can continue to be seen as a successful and innovative company.

REVIEW OF SECOND QUARTER FINANCIAL RESULTS:

Uber P&Ls improperly comingle operating results with claims about the value of financial instruments unrelated to its ongoing operations and markets

As this series has documented repeatedly, Uber’s accounting practices make it extremely difficult for investors to understand current financial performance and profitability trends.

Uber abandoned several overseas markets that had been financial disasters, including China, Russia, India and Southeast Asia. More recently it has also ditched all efforts to develop autonomous vehicles, and various other speculative longer-term business development opportunities. In each case, a larger market player benefitting from reduced competition gave Uber a consolation prize: some non-marketable debt and equity instruments.

Prior to 2017, Uber carefully segregated financial data about ongoing and discontinued operations. But when Uber was desperate to show strong profit improvements in its IPO prospectus, it inflated its 2018 P&L results by $5 billion based on its claim that the equity received from Didi Chuxing in 2016 in return for shutting down Uber China had massively increased in value. This claim was unverifiable since there was no market for Didi stock and Didi (like Uber) was massively unprofitable [A2] and Uber wrote off much of the claimed appreciation after the IPO.

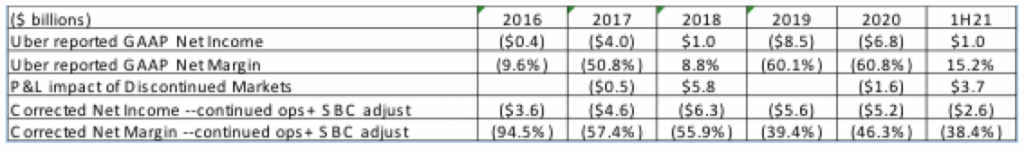

While it is extremely difficult to identify the separate financial results of Uber’s failed and continuing operations from the data in its SEC filings, this series has documented the accounting issues in detail and has restated its 2017, 2018, 2020 and now 2021 reports so that the results of continuing operations can be identified. [A3]

Uber had a negative 38% profit margin in the first half of 2021

To make sense of Uber’s 2021 results, it is necessary to split out huge ($3.7 billion) claimed gains from securities from discontinued markets from its marketplace performance in continuing markets. The table below incorporates that restatement of 2021 results with previously published restatements of 2016-2020 results.

Uber’s published financials suggest that its business is subject to multi-billion dollar up and down swings that have no relationship to any observable market changes. In reality, its business has produced huge negative margins over the last five and a half years that have declined somewhat but have been largely steady.

In the first half of 2021, Uber’s continuing operations had a negative 38% net margin, restoring loss levels Uber had experienced in 2019 prior to the pandemic. As discussed in Part Twenty-Four, Uber massively cut costs and eliminated activities not directly supporting their core taxi and food delivery businesses in 2020, but could not cut enough costs to match the pandemic driven revenue collapse.

Uber’s reported 2021 results were distorted by the inclusion of a claimed $1.4 billion gain in the value of Didi stock it holds, and a $2.0 billion value in Aurora securities received when Uber finally abandoned the autonomous vehicle business. That Didi gain was based on Didi’s value the day after its IPO, which happened to be the last day of Uber’s second quarter. As discussed in Part Twenty-Five the value of Didi stock has since fallen 50%, which undermines the credibility of Uber’s published claim that it earned GAAP profits in the second quarter and suggests that Uber’s third quarter P&L results may be seriously depressed.

As previously noted in this series, it is impossible to estimate the separate profitability of ridesharing and food delivery, or how the profitability of each business is changing over time from the very limited data Uber includes in its SEC filings.

But despite major flaws in the metric used (discussed below), food delivery appears to be a financial disaster that significantly reduced Uber’s GAAP net income. Even after excluding large chunks of relevant costs, the contribution margin of food delivery was negative 10% in the first half of 2021 and was 30 margin points worse than ridesharing.

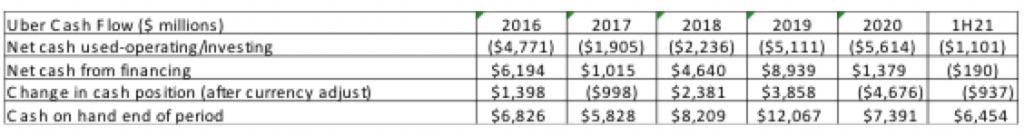

Uber is still cash negative although major cost cutting has slowed the cash drain

After having declined by $4.7 billion in 2020, Uber’s cash position declined by another $937 million in the first half of 2021. Uber now has $6.4 billion in cash on hand. This is an $8.2 billion decline from the peak $14.6 billion on hand immediately following the 2019 IPO. It is highly likely that the elimination of long term activities in 2020 such as autonomous vehicle development significantly reduced cash drains and the increased food delivery activity made them worse, but Uber does not provide investors with sufficient data to develop reasonable estimates. It also does not provide investors with sufficient data to understand the cash flow of its operations in different international markets.

Uber aggressively uses its fake “Adjusted EBITDA profitability” measure to distract attention from its terrible actual profitability.

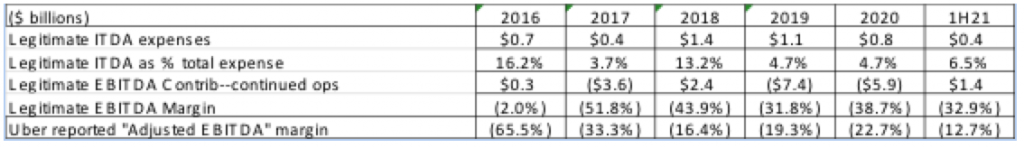

As this series has noted multiple times, the “Adjusted EBITDA” metric Uber highlights in its quarterly financial releases is not an honest measure of anything an investor might actually care about. It is not a measure of any type of profitability, and it does not even measure EBITDA.

A legitimate EBITDA metric would only exclude interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization from total expenses, and would also need to only show results from ongoing operations. As the table below indicates, legitimate ITDA expenses at Uber are only about 5-6% of total expense, so legitimate EBITDA closely tracks GAAP net income.

Uber excludes additional expenses from “Adjusted EBITDA”, including its very large stock-based compensation expenses, and its COVID response initiatives that would not be excluded from any legitimate EBITDA measure, because they are not exceptional one-time costs, and can vary widely from period to period. Uber’s “Adjusted EBITDA” metric gives it the ability to manipulate how much (fake) profit it earned each period, and allows it to mislead investors about how fast Uber is approaching profitability and how far it has to go.

Uber’s “Segment Adjusted EBITDA”, its fake measure of the separate profitability of its ridesharing and food delivery businesses is even worse. “Profitability” is calculated after removing another $2 billion in expenses, including the costs of developing and maintaining its app and IT systems and corporate G&A. This allows Uber to claim that its ridesharing business is already “profitable” even though it is cash negative.

Because of its much narrower business focus, Lyft’s 2021 margins have been slightly better than Uber’s, but profitability is still not on the horizon.

Lyft has very little exposure to non-US markets, so its 2021 results reflect the strongest possible short-term rebound from 2020 pandemic impacts. Because it was also not attempting to expand into a wide range of new businesses like Uber was, it was less distracted by painful restructuring efforts after the pandemic hit. Since Lyft did not experience any of Uber’s disastrous failures in overseas markets or new business ventures, its P&Ls are not distorted by combining any claimed securities valuation changes with the results of ongoing operations.

Lyft’s first half 2021 net margin was negative 49%, versus negative 42% in the second half of 2019 (the strongest comparable per-pandemic period) and versus negative 38% for Uber’s continuing operations in the first half of 2021. Its ridership volumes, revenues, operating expenses and total expenses are all down 29-30% in 1H21 versus 2H19, suggesting that Lyft shrank costs closely in line with the market declines. It did appear to reach cash breakeven in the second quarter.

Lyft’s financial releases also emphasize “adjusted EBITDA profitability” so they can claim faster progress towards “profitability” than Uber, even though their GAAP net margins are lower. Lyft’s “adjusted EBITDA” metric excludes stock-based compensation expenses (about 15-20% of total Lyft expenses). Since these compensation expenses increase rapidly when revenue grows, excluding them allows Lyft to claim that second quarter revenue gains had a much larger “profit” impact than they actually did.

The financial press ate up Uber and Lyft’s fake profit claims and totally ignored the central economic issues

Uber and Lyft’s emphasis on fake profit measures successfully got the business press and Wall Street analysts to misrepresent their performance to their readers, and to completely ignore the questions of how Uber or Lyft could achieve the coming improvements in “adjusted profits” that their executives were promising, and what it would take for Uber and Lyft to actually achieve sustainable profitability.

Every mainstream publication falsely implied that the specific “adjusted EBITDA profitability” metric Uber and Lyft’s used was widely used and understood. The Wall Street Journal even offered the blatantly dishonest explanation that it merely “entail[ed] stripping out expenses such as asset write-downs that executives and many investors consider to be outside a company’s fundamental operations.” [A4]

None explained how it compared to GAAP profitability, and almost none of the stories about Lyft even mentioned its GAAP losses, focusing instead on how “Lyft has just won the race to profitability ahead of its ride-hailing rival Uber, but there are hopeful signs that the latter is not far behind.” [A5].

Reporters buried mentions of Uber’s claimed $1 billion GAAP profit deep in their stories. They seemed to understand that an increase in the value of Didi equity issued in 2016 had nothing to do with the true GAAP profitability of Uber’s core businesses, but never made that point directly, and since Uber had not provided them with a coherent measure of actual profit they placed even greater emphasis on the fake “Adjusted EBITDA” measure. [A6]

Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, which (unlike the mainstream business press) has always had an excellent grasp of Uber’s terrible economics, found that none of the Wall Street analysts that follow the industry seemed to have a clue about Uber’s actual financial performance. Grant’s noted that “After a projected $715 million adjusted EBITDA loss for 2021, analyst consensus calls for that line-item to swing to a positive $1.43 billion next year, then more than double to $3.47 billion in 2023. Free cash flow, penciled in at minus $1.8 billion this year, will swing to positive $553 million in 2022 and then quadruple to $2.36 billion the year after, if Wall Street is on the beam. Overall, 39 of the 44 analysts tracked by Bloomberg rate the stock “buy” or its equivalent, while the Street-wide average target price sits at $69 per share, about 60% above current levels.” [A7]

There is no evidence Uber’s investment in food delivery could ever be profitable

Unlike ridesharing, media stories about food delivery do highlight the central economic issues. Readers are told that no one in the industry has ever made money, recent growth depended on unsustainable levels of discounting and no one expects the lockdown-driven demand spike to continue.

Food delivery is much more competitive than ridesharing, neither Uber or other incumbents have any discernable competitive advantage and (as Uber has demonstrated) there are no meaningful barriers to new competitive entry. Even though they serve half the market and have the longest experience, Doordash margins have continued to decline, and at the height of pandemic only earned 90 cents out of each $36 customer order. Grubhub is refocusing on online services for restaurants; its CEO said that food delivery “is and always will be a crummy business” and that delivery/logistics was a commodity service that was “hard to leverage even with technology and scale.” [A8]

As noted, even by Uber’s dubious “segment adjusted EBITDA” metric food delivery margins remained negative ((10%) in the first half of 2021) and much worse (30 margin points) than ridesharing. This suggests that Uber’s food delivery is significantly cash negative, and the gap between current performance and true profitability is much larger than it is in ridesharing.

Contra Grubhub, Uber is doubling down on delivery logistics. They appear to believe they can find a technological solution to productivity and service problems that no one else has been able to discover. They also seem to believe they will find new ways to exploit the Uber app and brand even though there is still no evidence of operational synergies or pricing power large enough to have a material P&L impact.

Billions in venture capital failed to “disrupt” traditional food delivery economics. Rather than admit these investments have failed these companies will keep searching for ways to extract value from consumers and suppliers via consolidation or exploiting market or political power. Grubhub resulted from the rollup of 12 independent companies. Uber was unable to acquire Grubhub but did acquire Postmates and Drizzly. The food delivery companies, desperate to limit the power of their “gig” drivers, were major backers of California Proposition 22 and similar moves in other states. No one has ever explained why a low-value added supplier should expect to capture a much bigger share of the customer dollar (30% app charges) when the restaurant who was providing the product the customer actually cared about could only earn 3-5% margins, but abuses of restaurants have become legion. [A9]

Uber was highly unprofitable in 2019 and things haven’t gotten any better

In 2019 the GAAP profitability of Uber’s ongoing businesses was negative 40%, At that point Uber was flush with IPO cash, most customers believed Uber was a terrific service with good prices, and many drivers may have been frustrated with pay and conditions but saw it as a decent employment option. Uber had cutting edge technology that could tie all the pieces together and efficiently balance the supply of vehicles with the demand for rides. But as this series has discussed in detail, all of that depended on large and seemingly inexhaustible levels of subsidies. And absolutely no one could lay out a plausible path from 2019 market conditions and 2019 subsidy levels to sustainable profitability without subsidies.

The pandemic obliterated ridesharing demand. While a major rebound is visible in second quarter 2021 results and will presumably rebound further, a full recovery to 2019 market conditions isn’t on the horizon. The business and entertainment-related ridesharing trips in the relatively dense (and relatively wealthy) large urban neighborhoods that were the heart of Uber’s biggest markets are unlikely to return to pre-pandemic conditions anytime soon.

The crisis led to decisions that both hurt and helped Uber’s economics. Believing that the stock market would focus on raw volume and ignore profitability, Uber made a major new commitment to food delivery. This allowed it to trumpet the fact that current trip volumes are only 20% below late 2019 levels but it seriously weakened profitability and cash flow, and there is no evidence Uber could ever earn money in this business.

On the other hand, Uber aggressively eliminated costs that weren’t supporting near-term revenue generation, including all of its hopeless investments in future businesses such as autonomous vehicles. But there has never been evidence of operating scale economies in ridesharing. As revenues increase second quarter 2021 levels, costs will as well.

The disruption of 2019 market conditions also disrupted operational efficiency. Lower demand means lower vehicle utilization and driver earnings potential. If drivers can’t cover their daily costs, they won’t show up. The driver shortage triggers enormous pricing surges—July 2021 prices were 50% higher than December 2019 prices. [A10] But this doesn’t solve the underlying problem because drivers know it has become much harder to make money driving for Uber. The combination of the surge pricing sticker shock and the increased awareness that cars might not be available when needed drives away customers, so the downward spiral continues.

In the second quarter Uber announced that it would spend $250 million on bonuses in the hopes of keeping the driver shortage from getting out of hand. Car availability improved somewhat but many drivers said they would only drive when bonus or surge pricing conditions held. But Wall Street was spooked by the big P&L impact—the share of gross customer payments retained by Uber fell from 22% to 16%, the lowest level since Uber began publishing its financial results in 2016. Uber statements suggest that the bonuses have only helped car availability in the states that had terminated unemployment assistance.

Uber’s challenge isn’t the pandemic, it is the end of the infinite subsides needed to prop up a failed business model

Uber’s operating crisis has seriously, perhaps fatally, undermined the narrative that its stakeholders had accepted for so many years. Customers have begun to doubt their longstanding view that they could rely on Uber to provide service at good prices whenever they wanted. If current prices persist, they will begin to realize that Uber now costs more than the traditional taxi companies they drove out of business. Neighborhoods that traditional taxis could not serve profitably will begin losing service since Uber will not be able to serve them profitably either.

Even before the pandemic, drivers had become increasingly aware that Uber work is lousy, can only produce worthwhile income under limited conditions, and Uber was never interested in ensuring the economic interests of their “partner-drivers” were met. Drivers are fully aware of Uber’s desperate fights against any legislation that would increase drivers’ rights and are aware of how quickly Uber retracted increased driver autonomy (right to refuse trips, rights to set fares, etc.) after Proposition 22 passed. Drivers knew that Uber’s $250 million in bonuses would do nothing to permanently improve pay. Drivers are increasingly realizing they have much better employment options. [A11]

The pandemic operational crisis has killed the narrative claim that Uber’s wonderful technology could efficiently balance supply and demand. The pandemic driven restructuring also killed the investor narrative that Uber had numerous profitable expansion opportunities beyond ridesharing and would eventually become the Amazon of Transportation.

The question of how 2019’s gap between negative 40% margins and profitability has become more difficult. Anything that could be done in the near-term to address the needs of customers or drivers would make the negative margins even worse. There are no magical software or big data or other technological breakthroughs waiting in the wings that will dramatically reduce costs or boost productivity. Uber have already used market power to massively suppress driver compensation and to eliminate service and safety regulations that might have limited returns to capital.

Uber had never “disrupted” urban car service economics. It can no longer provide the subsidies to keep drivers and customers happy. As noted, Uber’s cash position has fallen by over $8 billion since the 2019 IPO. While it still has $6 billion on hand, a company that has lost $28 billion in the last 5 ½ years cannot expect to be able to raise significant new equity, and Softbank, its most important investor, has been desperately selling Uber shares to cover its own liquidity problems. Consolidation is not an option. Scale/network economies have always been limited, and Didi has proven that even a 90+% market share won’t produce significant pricing power.

None of the journalists covering Uber’s second quarter results asked how Uber could ever become sustainably profitable, and none of the executive presenting those results suggested they had any idea how that might be done. But the answer is simple. The path to Uber profitability does not exist.

_____________

[A1] Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Twenty-Five: Didi’s IPO Illustrates Why Uber’s Business Model Was Always Hopeless, August 2, 2021

[A2] “Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Nineteen: Uber’s IPO Prospectus Overstates Its 2018 Profit Improvement by $5 Billion” April 15, 2019

[A3] Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Twenty-Two: Profits and Cash Flow Keep Deteriorating as Uber’s GAAP Losses Hit $8.5 Billion, February 7, 2020; Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Twenty-Four: Uber Loses Another $6.8 Billion, February 16, 2021. The restatements of pre-2019 results also spread Uber’s stock-based compensation expense over a four-year period. GAAP rules required Uber to nearly $5 billion in in the third quarter of 2019, when its IPO was completed, even though these expenses were obviously not related to third quarter 2019 operations but to operations over a longer period of time.

[A4] Preetika Rana, Lyft Reaches Earnings Milestone as Demand Recovers, Wall Street Journal, Aug 3, 2021

[A5] Chris Nuttall, Lyft and Uber’s fork on road to profit, Financial Times, August 5, 2021

[A6] Kate Conger, Uber shows signs of pulling out of its pandemic slump, New York Times, Aug. 4, 2021

[A7] Almost Daily Grants, August 5, 2021

[A8] Heather Haddon and Preetika Rana, DoorDash and Uber Eats Are Hot. They’re Still Not Making Money, Wall Street Journal, May 28, 2021, Tricia McKinnon, Why DoorDash & Other Delivery Apps Struggle with Profitability, Indigo Digital, March 16, 2021

[A9] These include contracts limited their pricing freedom, premium charges for high app listings and the creation of false websites and phone numbers to prevent customers from contacting them directly Maureen Tkacik, Restaurants are barely surviving. Delivery apps will kill them, Washington Post, May 29, 2020

[A10] Preetika Rana, Uber, Lyft Prices at Records Even as Drivers Return, Wall Street Journal, Aug. 7, 2021

[A11] Faiz Siddiqui, You may be paying more for Uber, but drivers aren’t getting their cut of the fare hike, Washington Post, June 9, 2021; Preetika Rana, Uber, Lyft Sweeten Job Perks Amid Driver Shortage, Lofty Fares, Wall Street Journal, July 2, 2021; Whizy Kim, Let’s Talk About The Real Reason Ubers Are So Expensive Now, Refinery29.com, July 7, 2021

Uber is approaching profitability in the same way a ship approaches thee Horizon.

And like the ship approaching the horizon Hubert is keeping an accurate log.

The media love affair with Uber is baffling. Same with investors, who keep shoveling money into the Uber furnaces. I recall reading entries in this series back in 2017 that concluded Uber was burning through about three billion a year in losses. The IPO couldn’t have been more timely, as an infusion of cash was vital. With six billion or so in cash reserves, Uber has, what, two more years or so before the next infusion? From where will that cash come?

I speculate that some investors look at Uber as the Amazon of transportation. Amazon did have unprofitable years while it was undercutting its competitors and putting them out of business, but you could see a path to profits. Can’t say the same for Uber. Moreover, the cab and livery services that have survived are the better ones, at least from my vantage. Uber will not drive their competition out of business. And that is the point: the business model seems to be to subsidize fares, drive the competition out of business, and then raise prices in a largely unregulated environment. Won’t happen.

The whole of the Uber story reminds me of the behavior of Cargo Cults that emerged on Pacific islands that had seen U.S. military occupation during WWII.

The particular behavior I’m thinking of is rooted in the belief that piling all your wealth in a heap, somehow, magically makes it increase.

Cargo cultists are often encouraged to engage in ceremonial behavior where an individual or a group are expected to gather all of their ‘cargo’, which consists of artifacts, things of all sorts originating in the period of American military occupation.

In the case of an individual, the ceremony might consist of “Playing the pans” all their ‘cargo’ is put into a couple of metal pans, the sort you might use for washing dishes, and the leader of the ceremony pours the contents back and forth between the pans while the owner expects the contents, his or her ‘wealth’ to magically increase.

What is actually happening is the person manipulating the ‘pans’ is, through slight of hand, removing objects, stealing from the believer.

The same process can be applied to a whole village, in either case, when the expected increase in wealth fails to appear, when in fact deficits are the result, it is blamed on the participants ‘lack of faith’ or dishonest failure to contribute all of their ‘cargo’ to the effort.

The clandestine nature of the ‘redistribution’ of ‘cargo’ wealth achieved through the phony ceremonial grift results in tensions that are socially destructive.

It seems that taxing away billionaire’s wealth to stop them from buying our government is not the only control that goes missing when those taxes are eliminated. That extreme wealth is also used in irrational ways like investing in broadly damaging schemes like Uber and Lyft whose value is illusory, and actual impact is negative.

Uber, and Lyft, much like Cargo Cult leaders have amassed a tremendous pile of ‘investments’ which it promises will magically grow to the profit of investors, but which actually enriches only the corporation’s principals, leaves investors with losses, and causes all sorts of trouble in the process.

But if some ( or all) of Uber’s investors are deep pocketed social sadists who want to see Uber destroy a living-earning taxicab sector and bankrupt mass transit facilities all over America and do other things to precarify the society, then perhaps the loss of mere money is worth it to the deep pocketed investors , who gain more visible misery throughtout society than the money they lose.

I think you’re describing ‘Social Engineering’.

Where have I heard that term before?

Uber and Lyft are like the Freddy Krueger and Jason Voorhees of the financial world. No matter how many time you think that they have died, they come back. And here is the thing. Under a real capitalist system, they should be long gone as the only thing that they are competent at is making billions of dollars disappear each and every year. Under a classic capitalist system, they should have gone bankrupt, the asses liquidated to pay off what debts can be paid, and the people move on to different places. In other words, an inefficient corporation would be wound up and the resources re-allocated to more efficient organizations. But we don’t live under a classic capitalist economy but a completely rigged one which is why corporations like Uber and Lyft are allowed to survive. And it works – until it doesn’t.

In other words, an inefficient corporation would be wound up and the resources re-allocated to more efficient organizations. But we don’t live under a classic capitalist economy but a completely rigged one which is why corporations like Uber and Lyft are allowed to survive. And it works – until it doesn’t.

It seems kind of creaky today

What is this “classic capitalist economy” for which you yearn? I suspect it’s something like the former Soviet Union in the 1990s. A libertarian free-for-all in which the only point to any activity is if it makes money. Nothing need stop people selling drugs or guns to children so long as it’s a profit-making activity. Uber is vile and dangerous not because it can’t make a profit but because it destroys our public transport systems while brutally exploiting its non-union workforce.

I’d also be interested in learning what you mean by liquidating asses.

It was a mistake obviously but when I think of the pointy-haired bosses, it may not be a bad idea. But I don’t yearn for a capitalist system. It as proven itself no fit for purpose but we aren’t even asking ourselves really what to replace it with. And if we don’t, we may end up with a subsistence economy down the track.

Rev, they make soooooo much money in their IPOs that they have a “trust fund” that they can burn through for years and years and years and years…..

Uber’s lack of a profitable business model is largely irrelevant to the world. What matters is the purpose of Uber: to destroy public transport and flood our streets with even vaster numbers of private cars than currently clog them. I really don’t care that Uber can’t make a cent, a penny or any other currency. I want our governments to destroy Uber & Lyft, whether by taxation, regulation or any other legal method.

Prop 22 requires something like 7/8ths to overturn?

“After the effective date of this chapter, the Legislature may amend this chapter by a statute passed in each house of the Legislature by rollcall vote entered into the journal, seven-eighths of the membership concurring, provided that the statute is consistent with, and furthers the purpose of, this chapter. ”

https://calmatters.org/politics/post-it/2020/10/california-amendment-threshold-proposition-22/

So the law will still be there even if/when uber bites the dust…

That’s a concrete increment right (pun intended) there.

(meant to reply to james 10:29)

I’ve read elsewhere that a plan is to pursue the restoration of pre prop 22 labor rights evisceration will be at the federal level.

Also read elsewhere, the sharing vaporware was never more than a veil for “disrupting” the costs of labor. Mission accomplished.

Is food delivery such a bad business? My local pizza place seems to do fine delivering.

And how is Drizzly not profitable? I wonder why Domino’s never pivoted to include alcohol.

Pizza is a completely different animal than random food delivery. Its not even apples to oranges. Its like apples to pizza. So many people are going to buy pizza, so making investments in drivers, especially chronically underpaid ones, works out. Then the pizza buying behavior is so well known, operations can be made around it. The mark up on pizza is hideous, no matter how cheap it seems. Its easy to store in a vehicle. Its not labor intensive to make. Forgot pepperoni? Hey, look someone ordered cheese just now. The delivery guy spends no time at the door because its in a box. There is no, “is this order right,” beyond cracking open the box. Pizza takes no time to make. The ingredients are not the kinds of things that go bad, so there isn’t a risk of running out of ingredients.

I remember during the first break from undergrad where we were home on a Wednesday, my high school friends and I were hanging out in this kids basement and we tried to order pizza after 9pm because it was suggestion by one of the kids who went to a nearby local college. We found out they only deliver to the immediate college area after 9pm, and we needed it to be delivered at that time. Though we were equidistant from the college area to the pizza place, they wouldn’t deliver to us that late because they didn’t have enough people in the area to sell the pizza.

They also know pizza is being bought for groups at home, parents with kids. They can tell you some crazy delivery time such as 45 minutes and get it in 20 minutes because pizza takes no time in those ovens and since its for a group they know someone is at the address who can pay. Coming by earlier than estimated isn’t a potentially wasted trip.

Pizza is the business of the future, the entire Italian economy runs on selling pizza and a few fiat cinquecenti

Outstanding work, as ever

Another year, another Nimitz unit sunk.

> Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, which (unlike the mainstream business press) has always had an excellent grasp of Uber’s terrible economics, found that none of the Wall Street analysts that follow the industry seemed to have a clue about Uber’s actual financial performance.

No clue. Obviously the analysts are completely useless and unfit for purpose, or is the right way to look at this they are totally fit for purpose in that misleading “inwestors” is their objective.

The financial press is complicit in this scam. I don’t know if this is because they are lazy, ignorant, or greedy (no one really want to pay analysts for bearish outlooks. Short investors don’t rely on others for analysis.)

Speaking as a casual observer, it sounds like Uber’s unpredictability stems from the great expense of overpaying its executives. That could change, obviously. What then?

Correction: unprofitability