Yves here. On the one hand, it’s good to see that some have not forgotten about the huge distortions created by “heads I win, tails you lose” regimes like limited liability companies, particularly since the financial crisis showed how costly they can become. On the other, the question has largely disappeared from the policy radar, save for Elizabeth Warren’s idea of creating a special bankruptcy regime targeting private equity owned companies that would force them to bear more cost than just an equity wipeout.

Charles Goodhart proposes a regime that has partnership-like features, in that the “deciders” at a company face liability of one or even a multiple of their accumulated revenue while in power. Another proposal along these lines was devised, by of all people, former Goldman partner, then New York Fed chief William Dudley, that bankers at TBTF banks have a significant amount of their pay retained at the firm, as subordinated equity. If the firm went bust, their retained comp would be torched first. The dollar protection might not be all that large, but the impact on behavior almost certainly would be.

By Charles Goodhart, Emeritus Professor in the Financial Markets Group, London School of Economics. Originally posted at VoxEU

A predominant example of moral hazard is the application of limited liability to the shareholders of publicly listed private-sector corporations. This column argues that changing the incentives for senior employees and majority shareholders for listed firms may be the most effective form of regulation. The author suggests that creating a system where managerial staff and other shareholders are incentivised to adhere to best practice to protect themselves, as well as the firm in question, is optimal.

Moral hazard occurs when the ‘costs’ of a bad outcome of a (predictable) risk fall, in part or in whole, on someone other than those taking the risk, while at the same time benefiting from good outcomes. If the probabilities of that risk can be ascertained in advance, then, in principle, the risks can be insured and the risk taker will have to pay a higher premium, for example for obligatory flood insurance on a house built by a river. In this case, the moral hazard would then disappear. Otherwise, moral hazard leads those subjected to it to take excessive risks.

While concern about such moral hazard has been widespread in macroeconomics, the application of this concept has been quite selective, usually focussed on occasions when the state has chosen to bail out persons and/or institutions that have fallen on hard times. What has been mostly missing from such discussions in recent decades has been the realisation that in capitalist macroeconomic systems, the predominant example of moral hazard has been the application of limited liability to the shareholders of publicly listed private-sector corporations.1 Thus, if such a company goes bankrupt, the costs involved do not fall fully on its owners, but are generally passed on to its other creditors. This naturally leads shareholders to pursue riskier and sub-optimal strategies.

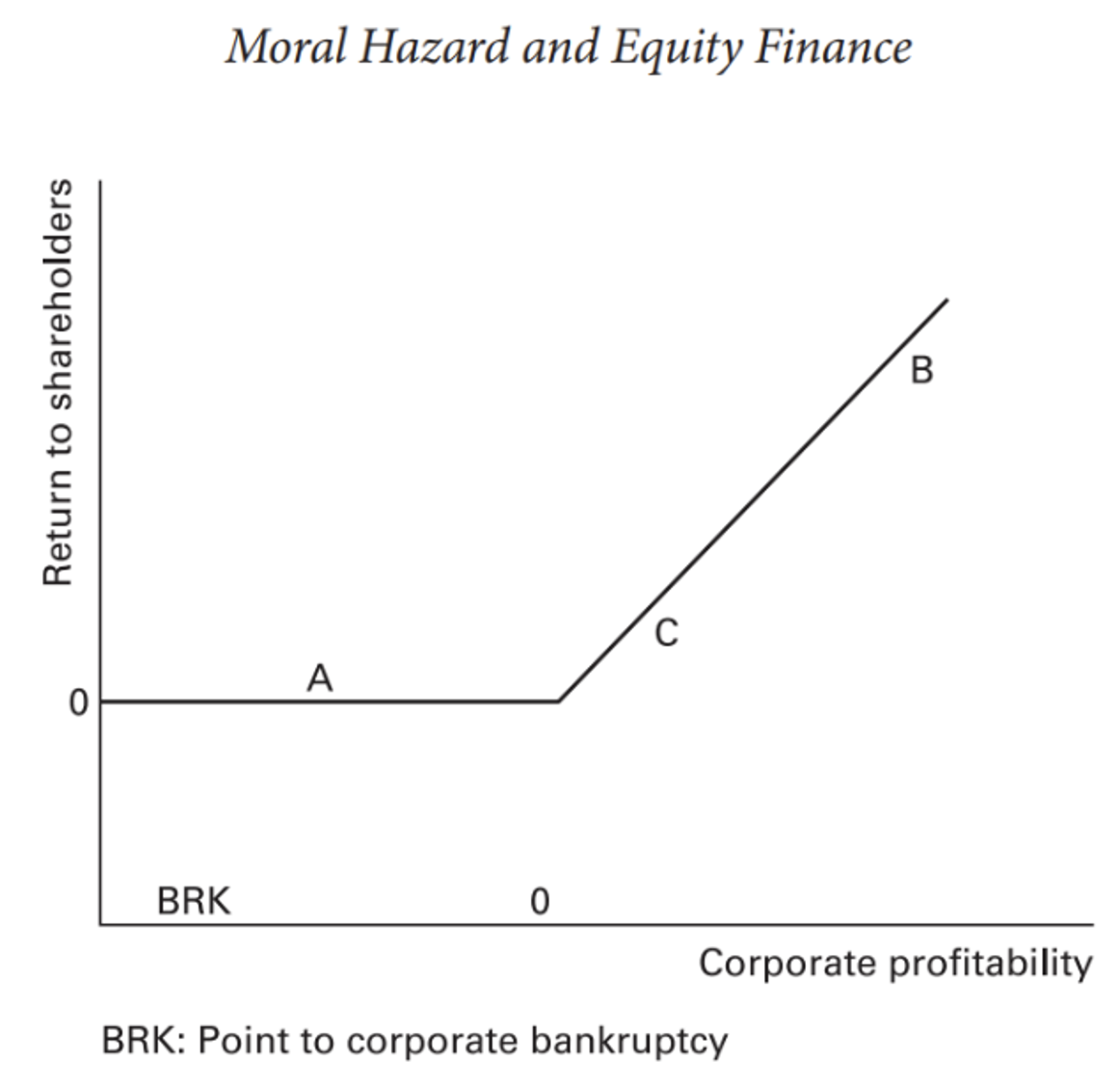

A consequence of limited liability for shareholders is that the return to their investment, as a function of the profitability of the firm in which they have an equity share, is flat when the company is doing badly or becomes insolvent but slopes upwards strongly when the public company is doing well. This is shown graphically in Figure 1 below.

With a return structure of this kind, the shareholders are led to prefer a riskier strategy, with an even chance of an outcome of A and B, receiving a return equal to the mean profit to the corporation of ‘AB’, rather than a completely safe policy (as shown in the diagram at point C). So, shareholders have an innate preference to encourage management to take on riskier activities. Such shareholder preference for risk is somewhat abated by loss aversion (see, for example, Kahneman (2012)). But that, in turn, is reduced by appropriate diversification, so that the loss involved on any single portfolio holding is limited. So, the implication is that limited liability naturally leads shareholders to push management to adopt riskier strategies than would be socially optimal.

Figure 1 Corporate bankruptcy

In earlier decades, before the 1990s, this pressure on management was mitigated by the fact that managers were primarily paid by a cash salary unrelated to equity valuation. Moreover, other considerations, such as reputation and pride in developing a successful company over the long term, had the effect of constraining managers’ willingness to take on risk. But one of the other possible incentives on managerial behaviour, as a result, was to spend resources on activities that might bolster managerial reputation and personal comfort, rather than maximising profits. This involved size and spending money on managerial perks, including perks such as company planes and chauffeur-driven cars, as well as fancy, prestigious architecture, head offices, etc. The cry went up, as a result, that managerial incentives should become better aligned with the interests of shareholders – possibly one of the worst ideas developed by academic economists in recent decades.

Partly in response to public attitudes about soaring managerial pay and perks, President Clinton introduced measures in 1993:

“…when he effectively set a $1 million limit on directors’ pay by making anything above that level non-tax deductible for companies. However, in the small print of his legislation, was a clause that specified payments with performance conditions were exempt from the $1 million rule. That effectively meant company boards boosted all salaries to $1 million and paid bonuses and extras in stock options that directors could cash in for shares at a later date. This prompted an explosion in executive awards…” (Hargreaves 2018)

The result of such alignment of managerial incentives with those of shareholders, in some large part done consciously, resulted in there being the exact same incentive on management to give priority to policies that would maximise equity valuation. Naturally, this would generally lead them to pursue additional risk. Moreover, the expected lifetime incumbency of most CEOs is relatively short ¬– five years or less – and this means that the incentive on them is to maximize short-term equity valuations. This can most easily be achieved by accepting a riskier financial structure (e.g. share buybacks), reducing employee headcount, and cutting out such longer-term investment (notably in research and development – the return on which was unlikely to become clear for a long time).

Is Regulation the Answer?

Faced with the likelihood that limited liability, especially with managers’ remuneration being concentrated in share options, would lead to excessive risk taking, the standard response has been to impose direct regulations on the relevant sectors, particularly and notably banking and finance, together with measures to reinforce transparency. There is a full panoply of regulations on banks, with respect to reporting, capital, and liquidity requirements, supplemented with regular stress tests to explore how such banks would fare under certain adverse hypothetical conditions.

But trying to constrain moral hazard by regulation and transparency has some inbuilt shortcomings. The first is that, by leaving the incentive structure of those taking the decisions unchanged, it leads the regulated to seek to find ways to get around, to manipulate, the regulations and requirements in pursuit of an improved return on equity (or ‘RoE’). So, regulation becomes an ongoing battle of wits between the regulated, seeking to amend, to find loopholes, and to refashion the regulatory system to their own benefit, on the one hand and the regulators, seeking to shore up the system, on the other. In this battle the regulated have the advantage of much greater resources, the ability and incentive to innovate, and a closer involvement with current operational developments. Regulators are always playing catch-up.

The second problem is that the incentive structure of the regulators, and of many of those charged with the role of providing transparency about financial conditions (e.g. accountants and credit rating agencies), are also subject to pressures akin to moral hazard. Let us take some examples of this. How should a regulator decide when a bank was failing, or likely to fail? The earlier this is done (no forbearance), the less will usually be the losses entailed and the potential for a contagious, systemic collapse. But by the same token, the earlier a regulator tries to close a firm, the greater the possibility that that firm would not have ultimately failed. If a regulator seeks to close a firm before it has become incontestably insolvent, she risks lawsuits and ferocious press briefing in opposition. Regulators themselves gain little, or nothing, from closing institutions before they absolutely must do so.

Similarly, accountants and credit rating agencies are paid by their clients. There is every incentive to give a client the benefit of the doubt, subject to the need to maintain a good reputation. But good reputation is a general, overall consideration, whereas the profitability relationship with each individual client is specific to certain employees in the accounting firm. An auditing accountant is almost bound to want to help each client as far as the law, and some generalised concern about reputation, allows.

In this context an alternative approach to such moral hazard is not to regulate, but to change the incentive structure of all those immediately involved.

Reforming the Incentive Structure for Corporate Managers and Other ‘Insiders’

Current criticism of the incentive structures of corporate managers in modern capitalism has several facets: it is argued that it leads to managers assuming excessive risk, being overpaid, and failing to undertake sufficient long-term investment, especially in research and development.2 The first two criticisms, excessive risk and excessive pay, were particularly levied at banks and other financial intermediaries in the aftermath of the Global Crisis. There have been a variety of proposals aimed at checking or preventing such malfunctions. One such set of proposals has focussed on limiting the business structures of banks and other financial intermediaries. Examples of such proposals include narrow banking in various guises, the ringfencing of core retail financial structures, and a variety of other regulatory measures.

Our proposal – as set out in Goodhart and Lastra (2020) – is to instead apply a distinction between a class of ‘insiders’, who should be subject to multiple liability, and ‘outsiders’, who would retain limited liability. So, for the ordinary shareholder there would be no change. Such a scheme obviously involves making a distinction, which must be inevitably somewhat arbitrary, between ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’.

In principle, the distinction is straightforward. ‘Insiders’ have access to significantly greater information about the working of the enterprise than ‘outsiders’, and the potential to use that information to prevent excessively risky actions. In practice, of course, the distinction is not so easy to make. ‘Insiders’ would include all the board of directors, including the externals. For employees, we would suggest a two-fold categorisation, by status within the company, and by scale of remuneration. Thus, any employee on the executive board, or who was chief of a division would be included. But the key players in a company are frequently indicated by the scale of their remuneration rather than by their formal position. So, any employee who was earning a salary in excess of, say, 50% of that of the CEO would also be assessed as an ‘insider’. Nevertheless, if the potential sanction of multiple liability arising from failure was regarded as severe, there could be attempts to adjust titles and salaries so as to avoid being categorised as an ‘insider’. So, the regulatory authority should have the right to designate anyone in a particular company as being an ‘insider’, subject to judicial review.

Large shareholders are also in a position to access inside information, and to exert influence on the course that a company might follow. So, any shareholder with a holding greater than, say, 5% of the company should also be regarded as an ‘insider’. There is no particular key threshold above which a large shareholder should be regarded as an ‘insider’. It is arguable that one should give shareholders holding between 2-5% of the value of the shares the ability to choose whether to count as an ‘outsider’, or as an ‘insider’. If they want to count as an ‘outsider’, they would have to give up all voting rights and not participate in policy discussions (e.g. at AGMs).

The base to which the liability should apply would be the remuneration of all those counted as ‘insiders’, cumulated from the date that they took on that role. This would apply to all forms of remuneration, except those provided in the form of ‘bail-in-able’ debt, with all subsequent transactions in such debt having to be notified. This would apply to the directors and employees. Shareholders would be liable according to the par value of their shares.

Not all ‘insiders’ are created equal, however. In particular, the CEO has much more information and power than any of his subordinates, other members of the board, or the auditors. One might think that the CEO’s liability could be three times the accumulated relevant value of remuneration (excluding ‘bail-in-ables’) from the time that he or she had taken up that role. Board members and chief officers of the company might have two times liability, and every other ‘insider’ employee a single liability equal to their accumulated revenue. Similarly, large shareholders with greater than 5% holdings might have double liability (i.e. for an additional twice par value of their shares), while ‘insider’ shareholders (between 2-5%) might be liable to pay in an additional par value of their shares – as in the American National Bank system before the 1930s.

This raises two further questions. The first is what should happen when an ‘insider’ ceases to play that role (e.g. an employee leaves the company), or a large shareholder sells their shares. The second is that an ‘insider’ may be aware that the company is entering dangerous territory but cannot persuade management to change direction. In that case, how could they avoid being sanctioned for a policy that they would not themselves advocate?

In the first case, of departure from the role of ‘insider, it would seem appropriate to taper the liability according to the degree of insider knowledge and power. Thus, if it was agreed that the CEO should have a three-times extra liability, then that liability would decline at a constant rate over the following three years, leaving the CEO with zero further liability exactly three years after they had left. By the same token, those with a two-times additional liability should have it taper at a constant rate until they were free of any further liability after two years; and so on for those with a one-time additional liability.

Then we come to the second issue, which is the question of how those with additional liability can avoid sanction in those cases where they have opposed the policy but have failed to succeed in changing it. Our suggestion in this case is that those in such a position should address a formal, but confidential and private, letter to the relevant regulators, setting out their concerns about the policy being followed. The regulator would have to formally acknowledge receipt of such letters, and they could then be used in mitigation, or often abandonment of any sanction, should the company then fail. Moreover, in the event of the company failing, for the reasons indicated in such a letter(s), this would in turn act as a form of accountability for the regulators. All such letters would have to be made publicly available in the event of failure. It would be a legal offence for the regulator then not to publish any such letter.

There is a more difficult question of whether the regulator, having received such a private confidential letter of warning (perhaps from the auditor, or an unhappy employee), should make it public. In our view, such warnings need to be investigated further by an independent body, such as the regulator or a financial ombudsman before being made publicly available, since in many cases, they may well be groundless with the maintained policy of the company being appropriate. But if the regulator, after investigation, should feel that the warnings had merit, the first step would then be to have a private discussion with management on the merits of the case, and, if management remained unmoved, the next stage would be to publish the warning (anonymously) together with the regulator’s own assessment, at the same time offering management the opportunity to state publicly their own side of the case. When the latter process had been completed, ‘outsiders’ would then be as well informed as ‘insiders’ on the merits of the issue.

Note that it puts regulators in the firing line for at least severe reputational damage, if they receive such warnings, fail to act upon them, and the warnings prove prescient.

But on this view, we need to go even further in order to encourage regulators to act promptly to intervene in banks. One possibility would be to require regulators to send in an independent auditor to check the conditions of any bank whose probability of default, as measured by one of the standard measures using market value data, exceeds some trigger value on average over a number of consecutive days. Another would be to require that all those in the supervisory body responsible for closing a bank get a bonus, say of 25% of their salary, to be paid by levying a malus (of the same amount) on all those responsible for the previous supervisory assessment of that same bank. Those continuing to supervise the same bank would be unaffected, but there would be an incentive to potential leavers to a new position to make sure that they were handing over a sound bank, and to new incomers to be more challenging about the health and condition of their new charge.

In a somewhat similar vein, one might require that the prior audit fee for any firm going bankrupt in, say, the following six months after the audit be handed over to the fiscal authorities, unless the accountancy firm had specifically qualified the audited accounts in a manner germane to the subsequent failure. There may be better ways to give a pecuniary incentive to the auditor to expose, rather than to paper over, weaknesses in the firms being audited, but the objective is clear enough.

The purpose of the exercise is to provide appropriate sanctions for failure on those with ‘insider’ knowledge and power. The particular illustrative numbers chosen in the above section are, obviously, somewhat arbitrary. But the exercise can be calibrated to impose appropriate sanctions for all such ‘insiders’, whether large shareholders, key employees, auditing accountants, or regulators. We think that this would be a better form of governance.

Conclusions

It is the thesis of this column that the most pervasive and damaging form of moral hazard is that occasioned by the interaction between limited liability and the alignment of the incentive structure of senior managers with those of shareholders, via bonus payments in equity (options). Both here, and in several other papers, I argue for a realignment of managerial incentives by removing part, or all, of the protection of limited liability from senior managers.

By much the same token, the incentive structure for regulators encourages them to delay closure until bankruptcy is incontestable, and for accountants to pander to their auditing clients as far as the law and a generalised concern with reputation allows. In both such cases I suggest ways to shift such incentive structures in order to achieve greater toughness of behaviour.

See original post for references

Ideally, yes, limited liability, especially in the case of private equity should be questioned.

To be honest, I think we should outright ban private equity at this point. What social value does it truly serve, save for being a source of rent seeking for the very wealthy? Matt Stoller had a good piece on this.

https://mattstoller.substack.com/p/why-private-equity-should-not-exist

At the very least, yes Warren’s bill should be passed. Dividend recapitalization too should be heavily restricted and ideally barred – it basically leaves otherwise viable businesses irreparably harmed.

The biggest problem of all is not that we don’t know what should be done. It is that private equity has become a politically powerful source of campaign donations for corrupt politicians and lobbying. They aren’t going to be go down without serious opposition.

Good point. Private equity is just a dodge to avoid reporting requirements. It’s one thing if a firm is a family business which wants to remain non-public. Quite another for a big investment scheme to hide its operations from scrutiny.

Yeah I generally agree. The problems arise from 50 years of neoliberalism which have allowed and indeed encouraged the malign opportunities. Accountants encouraged me all the time to avoid (not evade – that’s illegal) taxes when I ran a biz. My MMT brain helped me accede but my “seeing real life” bit recognised that I was perceived as part of the problem.

My only “material contribution” to the problem was helping companies sell crap. But overall across my career I’m satisfied I did more good than harm. Trouble is that doesn’t pay the bills/protect health etc.

I certainly think that whilst the death penalty is wrong for most people (even serial killers) ironically I support it for certain crimes…. those involving senior people whose ethos poisons our culture and “normalizes” behaviour of the sort this article discusses. Stop the rot. From the top.

Seems to me that we should kill the idea of limited liability across society, from political immunity to the LLC.

Anything less means taking the blindfold off Lady Justice’s eyes.

I like the idea of differentiated equity.

TBH, there are already differentiations between equity holders (often the IPOed shares are class B, allowing the founders to always outvote the plebs).

With power should come responsbility, so having a “LL equity” and “equity” would make a lot of sense.

In theory, the directors right now have responsibility (effectively unlimited), but in practice it’s nonexistent.

Making senior management to hold no-shield equity would work wonders for incentives IMO.

Maybe Sanders/Warren could pick it up, and run it on “personal responsibility” basis that the Republicans love to espouse so much. They could also point out that for the SME, the LL often gives no shield, as many banks want personal guarantee from the business owner. That is, unless you’re a lucky bastard that can raise a couple of millions for your startup from your rich mates

Thank you and well said, Vlad.

Goodhart has some personal affinity to such matters. He is descended from the Lehman banking family. One branch, as with some of the gilded age new money, came to England to mimic the British upper class. The family trust funds education at Eton and Oxbridge and, with regard to nephew David, rich kid pontification.

Goodhart’s colleague and successor at LSE and the Bank of England, Mervyn King, frequently tapped Goodhart for such reforms, but industry and political resistance, including from the Gordon Brown government, was too much.

I don’t know if it is possible to make directors more responsible. Hopefully it is possible but SOX-legislation did not appear to have done much more than increase fees paid to accountants.

https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/052815/what-impact-did-sarbanesoxley-act-have-corporate-governance-united-states.asp

I’ve seen a supposedly SOX-compliant company file (by mistake) false income statements for the better part of a decade. I’ve seen so many weaknesses in controls in companies that I have little confidence in responsibility being anything but a buzz-word used by directors to dazzle the less than experienced.

It might be possible to reduce looting by PE by changing legislation relating to payments to related companies, extend the time-period when payments (no matter what for) can be clawed back. But even if it would be possible to make such changes does anyone believe that the introduction of legislation without putting effort into enforcing it will change anything?

“In theory, the directors right now have responsibility (effectively unlimited), but in practice it’s nonexistent.”

Requirement to hold an unlimited-liability shares, and restrictions on their disposal are much stronger incentives than SOX or similar stuff. That depends on someone suing, and courts obliging. Bankruptcy is a bankruptcy..

There are still issues, like ring-fencing one’s wealth in a trust, so when the bankruptcy receiver comes after you, they find nothing, but those also can be dealt with by placing liens (i.e. any money you got from the company are “tainted” and have a lien on bankrupcty.. See, a case for perfectly-followable-crypto currency just here).

the suggestions are pretty good, but modify current law so that paying more $1 million dollars in one year, can be taken off your taxes, only if the that isnt more than say 40-50 times more than the average employees wages, for that company , and any subsidiaries and the industry the company is in, and that any stock options are paid out over a long term (say not less than 5 years). oh and the company has to been in business for more than 3 years and profitable, hasnt caused any harm to the location(s) they operate in.

I suggested something like this about 15 years ago.

I have mixed feeling about this suggestion. It seems good in principle, but I fear for a lot of devil in the details. The regulations may have to be way too complicated in practice. I also suspect that lots of lobbying would make this a non-starter, though this is cynicism rather than a reason to reject them outright. It also seems to me that that there are some easier remedies:

– make sure that the costs of share awards are accounted for properly. All too often the ‘adjusted’ figures exclude them.

– make sure the incentives are genuinely long-term. It would be easy to say, for example, that any shares, or options, received as compensation could not be sold until at least five or ten years after they were received. Perhaps allowing them to receive dividends might bring a return of focus on that old-fashioned value.

– some adjustments on what gets taxed and at what rate may help – as the article said, changes to this seemed to trigger the problem.

How’s this for a solution: If total remuneration exceeds that of the President of the United States, then 100% of that amount in excess of that amount can be clawed back in the first two years, 80% in the years 3 & 4, 60% in years 5 & 6, 40% in years 7 & 8, 20% in years 9 & 10 in bankruptcy proceedings.

To quote Billy Ray Valentine (Trading Places). “You know, it occurs to me that the best way you hurt rich people is by turning them into poor people.”

Directors will get insurance to cover the risk they might not get all their money. Same with the top executives. The insurance carriers would carry the risk. If not that a lot of very highly paid lawyers would figure out some sort of loophole. The best strategy would be to make it not worth while by simply taxing income over perhaps 200K at 80 to 90 percent across the board, eliminate deductions to foundations and every other strategy that is used. And as soon as a new strategy pops up tax it. Ain’t going to happen. Our Republic is finished as Gore Vidal pointed out. The next change, perhaps triggered by global warming or mass migration secondary to global warming, may well be dramatic and violent. Another 20 to 30 years of downward mobility for the natives might just do it. Right now what it looks like is a rabid money grab by finance, law and the politicians hoping all to make dynasty creating money to carry them through the coming crisis.

One addition to the potential regulation or other expanded communication could be modeled on past financial disclosures like Annual Percentage Rate. That APR notice helped reduce the mumbo jumbo used by lenders and brokers to hide an element of the borrowing cost. It also provided borrowers a slight reduction in the information asymmetry inherent in so much consumer finance.

Show explicitly the impacts on various classes of the positive and negative events. For example in the event of a bankruptcy, of whatever Chapter, identify in lay terms what happens to CEO, the directors, common or preferred shareholders, any general and limited partners, the managing member, the subordinate tranches or whatever. No more hiding behind the private equity or other smokescreen. Who gets what upon transaction, upon dissolution, upon bankruptcy or whatever course. Add a section about predatory characteristics and effects to sweep in payday lenders, student loan shops and their ilk.

Easier said than done, but with all that brain power working on the lower tip of Manhattan and elsewhere, someone could take a stab at it and make some dough and achieve notoriety.

hm, in bankruptcy, management seems to get ‘ bonuses’ when the company fails, even though its likely that the failure was their doing.

maybe make it so that they can get bonuses only if they are truly critical to the company, not just an insider, and the company cant take a tax credit for paying those bonus, and will struggle to convince the IRS that they are a going concern

There is a very good historical experiment on the effects of limited liability on risk taking from the 1800s.

The short version is that in the 1800s, Married Women’s Property Acts (MWPAs) were passed, which allowed wives to own their own property, so the things like family jewels and houses that they might have brought into the marriage were theirs rather than their husband’s.

It turns out that this made a big difference if you were a bank president in the 1800s, because if your bank failed, you were on the hook to the depositors, who could take every thing that you owned.

Every thing that you owned, but not what your wife owned, so if you lived in a state that passed an MWPA, and you had a wealthy wife, your bank had a significantly higher leverage rate:

Hoocoodanode?

I understand that this is from a academic leaning source, but to me it soft-shoes around the issue. The real issue is that our current structure tells senior management to do what they are doing. They are cutting corners on everything from product R&D (e.g., Boeing), customer service, employee safety, cyber security, pollution etc. The list of companies playing these games to enrich themselves and be gone when the bill must be paid is endless.

there is plenty of blame to go around for this mess that is for sure. but the author touches a bit on it, bill clinton.

i watched in the 1990’s as bill clinton took a meat ax to americas civil society with his free trade, deregulation, privatization and tax cuts for wealthy parasites.

i said about his deregulation of wall street, the banks, hedge funds etc, would leave america in a scenario where every place you went, everything you use, everything you touch, everything you need to live, a financial parasite would be feeding away on the life blood of america.

and that is where we are today.

wanna stop it? band aids will not do it.

bill clintons disastrous polices must be reversed, or we collapse.

if they can ever be reversed, then we can take away limited liability.

charter corporations for five years, every five years they must submit to revue by the public and labor.

one corporation cannot own another corporation.

a board member can only sit on one board at a time, no multiple boards. like board members from oil companies and insurance companies sitting on general motors board, advocating for policies that drive the cost of production up to the point where they can no longer compete.

limit total compensation to 33 times what the lowest paid employee gets.

proof that some of the profits are plowed back into R&D and local economy.

there is more i am sure, but this is a beginning.

Thanks for this piece, I say as I grind my teeth. The concept of limited liability as it exists is repugnant and in my humble opinion inherently unethical. The lack of liability/responsibility to the what would be called the general welfare or the commons (as Mikerw0 points out) has spread everywhere from lack of regulation as I see it. As someone mentioned, I agree with considering this as a personal responsibility issue, since that’s what’s we hear quite a bit about. However, personal responsibility applies only to the little people.

Off subject perhaps but I don’t think so, private equity run rampant looks to be our downfall as I continue to read NC. They buy up the housing market, physician practices, pet food companies, you name it. Effectively, they are becoming single market controlling entities. It’s almost worse than monopolization. There’s no liability or conscience. Ha. Perhaps sometimes they pay fines.

Just my mindset today: it occurs to me that all those “liabilities” are inevitable to someone, sometime. Whether or how they are avoided in the business world (take it off the taxes, etc.) should be regulated more in line with the cold hard fact that shit happens and somebody winds up paying. Usually up until now society pays them as socialized losses, insufficient taxes to maintain a good society, etc. But always it has been the environment that has absorbed the heaviest burden of exploitation for the sake of our profit. Corporate profit and nice salaries for managers. A “growing” economy. Underpriced resources. Whatever. The reason we have almost-unscrupulous accounting practices is because – competition. Better to have a practical, doable, rules-based economy that protects the environment and society. It doesn’t have to be based on profits. Nor competition for market share. It can all be reconstrued to work in relative harmony. Why not… it’s probably safer than hoping for better behavior with incentives that do not protect the environment.

JFYI, Jonathan Levy’s Ages of American Capitalism: A History of the U.S. notes that before 1980, the manufacturing sector got only 20% of its profits from finance (stock, interest, etc.). After 1980, that figure became 60%. The incentive to seek rent has tripled.