Yves here. I am sure readers can add to the list of infrastructure projects that wind up being a poor use of resources. One is sports stadiums, which are basically payoffs to real estate developers and construction firms. Studies have found that almost without exception, they fail to bring in enough in incremental tax revenues to justify their cost.

One obvious form of grifting is toll roads. A 2014 article on privatizations, describing the economics of new toll road projects, explains how they always go bust. I have seen no evidence that the structure or terms of these deals have changed to favor users and taxpayers. From Thinking Highways:

Beginning with the contracting stage, the evidence suggests toll operating public private partnerships are transportation shell companies for international financiers and contractors who blueprint future bankruptcies. Because Uncle Sam generally guarantees the bonds – by far the largest chunk of “private” money – if and when the private toll road or tunnel partner goes bankrupt, taxpayers are forced to pay off the bonds while absorbing all loans the state and federal governments gave the private shell company and any accumulated depreciation. Yet the shell company’s parent firms get to keep years of actual toll income, on top of millions in design-build cost overruns….

Of course, no executive comes forward and says, “We’re planning to go bankrupt,” but an analysis of the data is shocking. There do not appear to be any American private toll firms still in operation under the same management 15 years after construction closed. The original toll firms seem consistently to have gone bankrupt or “zeroed their assets” and walked away, leaving taxpayers a highway now needing repair and having to pay off the bonds and absorb the loans and the depreciation.

The list of bankrupt firms is staggering, from Virginia’s Pocahontas Parkway to Presidio Parkway in San Francisco to Canada’s “Sea to Sky Highway” to Orange County’s Riverside Freeway to Detroit’s Windsor Tunnel to Brisbane, Australia’s Airport Link to South Carolina’s Connector 2000 to San Diego’s South Bay Expressway to Austin’s Cintra SH 130 to a couple dozen other toll facilities.

We cannot find any American private toll companies, furthermore, meeting their pre-construction traffic projections. Even those shell companies not in bankruptcy court usually produce half the income they projected to bondholders and federal and state officials prior to construction.

And don’t get me started on high speed rail. What about “existing conditions” don’t you understand?

If you are going to propose a city pair, start by telling me where the terminus in each city is, where that is relative to the airport and any airport link to the city, and how much in the way of office building, retail and residential structures you have to buy up and tear down. High speed rail might have worked early in the post World War II suburbanization process. Real estate would have been developed in relationship to rail transit. There’s no way to do it well or effectively now.

By Richard White, Professor of American History, Stanford University. Originally published at The Conversation

Over the past two centuries, federal, state and municipal governments across the U.S. have launched wave after wave of infrastructure projects.

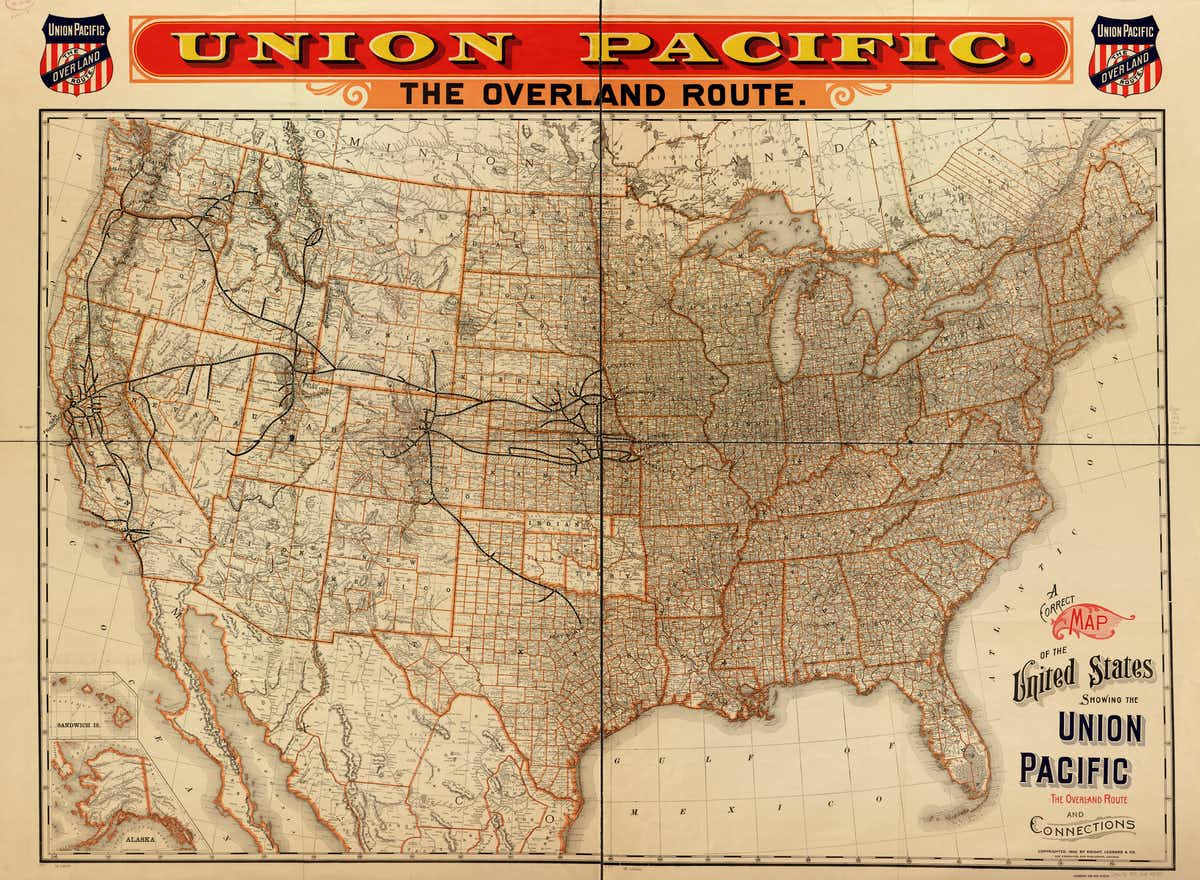

They built canals to move freight in the 1830s and 1840s. Governments subsidized railroads in the mid- and late 19th century. They created local sewage and water systems in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and then dams and irrigation systems through much of the 20th century. During World War II, massive amounts of public money were spent building and expanding ports, factories, airfields and shipyards. And after the war, highway construction – long a state and local project – became a federal endeavor.

Many of these projects did not end well. The problem wasn’t that the country didn’t need infrastructure – it did. And the troubles weren’t the result of technical failures: By and large, Americans successfully built what they intended, and much of what they built still stands.

The real problems arose before anyone lifted a shovel of earth or raised a hammer. These problems stem from how hard it is to think ahead, and they are easy to ignore in the face of excitement about new spending, new construction and increased employment.

The questions about which massive structures to build, and where, are actually very hard to answer. Infrastructure is always about the future: It takes years to construct, and lasts for years beyond that.

The money invested in roads, railroads, airports and dams cannot be repurposed, and what is built requires large future expenditures for upkeep. If the infrastructure isn’t needed, then we throw good money after bad.

Overbuilding

Obsolescence isn’t the worst of the potential problems that can come from infrastructure spending. Railroads dominated the 19th century, but the U.S. built too many of them, particularly into the lightly populated West. I spent a whole book discussing the many ways in which that work, lauded now as a great success of government funding for private infrastructure, was in fact a costly and wasteful failure. The costs began with the bankruptcies and repeated regional and national economic crisesthat 19th-century Americans referred to as “railroad depressions.”

Infrastructure is intended to promote development, and it will. But that can be a problem. There is such a thing as dumb growth, like the development that swamped 19th-century markets with wheat, timber and minerals that they could not absorb. The result was numerous business failures and the abandonment of whole geographic areas when the economy went bust, as during the Dust Bowl.

The economic damage the overbuilding of railroads yielded paled before the environmental damage wrought by the mining, clear-cutting and large-scale agriculture they encouraged. And this points to another problem.

Delayed Costs

People tend to disregard the long-term costs of the plans they make, particularly if they reap the benefits and others pay the costs.

In the early 20th century, municipal water and sewage projects were great successes. They probably had more to do with reducing disease than medical advances did. They made modern cities livable.

But they inflicted costs on others. Los Angeles became Los Angeles by draining water away from the Owens Valley, draining a lake and reducing farmland to desert. San Francisco became San Francisco by flooding the Hetch Hetchy Valley, which naturalist John Muir once called “a wonderfully exact counterpart of the great Yosemite.” The results may have been worth the price, but it is useful to recognize that there was a price – one that continues to be paid.

When launched, new infrastructure seems to be a list of benefits. In the mid-20th century, enthusiasts for hydroelectricity and irrigation saw all sorts of advantages as the government dammed Western rivers and irrigated Western lands. But many of these lands needed unreasonable amounts of irrigation to yield the desired crops. Dams utterly changed the nature of rivers and hurt the iconic species of the Pacific West, particularly salmon. It might have been helpful for builders to have had a little less faith that future technologies would correct the problems they foresaw.

Perhaps the greatest federal infrastructure system of the late 20th century is the interstate highway system. It changed the spatial arrangement of the nation and how Americans moved. It capitalized on the American car culture, until the interstates became crowded around cities they maimed and people confronted climate change, to which the cars on those interstates contribute so significantly.

In promoting infrastructure, politicians will tout jobs, economic growth and a whole array of conveniences and benefits. Citizens should be more sophisticated.

They should ask who – particularly which corporations and developers – are going to benefit from these projects. They should look beyond the price tag to the social and environmental costs. Building canals for a railroad age proved a great mistake. But climate change makes building an infrastructure for a carbon economy a far more dangerous endeavor.

Alas, under the Christian Democrat / Social Democrat coalition, now Germany is also headed down that PPP (public-private partnership) infrastructure road.

By awarding the Vinci contract mere months before an upcoming federal election, Merkel’s government is presenting the voting public with the start of German motorway privatization as a fait accompli. “Facts on the ground” and all that.

https://www.vinci.com/vinci.nsf/en/press-releases/pages/20210721-1820.htm

https://taz.de/Erste-teilprivatisierte-Bundesstrasse/!5792418/

Another boondoggle to track is slow urban light rail.

Local politicos love to cut ribbons to announce “we are so progressive”. Developers announce “walkable communities” on the line, i.e. cheaply built “luxury apartments” with muffin stores below and one or two “affordable” units for deflective PR. Then invariably a few months later the railcars shuttle back and forth almost empty because the apartment inhabitants never take public transportation. The huge debt (“Feds pay 1/3!”) and operations cost remain after the lucrative multi-billion$ consulting and construction graft. And the “cushy jobs for drunken slobs” (Monorail!) are $15/hr with drug tests but at least have AC.

Phoenix has a not very extensive light rail. I’ve ridden it but good luck getting many of the locals to show any interest. Serious commuters who don’t want to drive are more likely to use the express buses.

In Atlanta MARTA–which is an actual subway–has been more of a success as it can get you downtown faster than the clogged roads. But it still has limited routes in a city that is just as sprawling as Phoenix. As Yves says about high speed rail, the barriers to these projects in an already developed cityscape–built for cars–are huge. Making the cars more efficient may prove a lot more practical than getting people not to ride in them, at least here in America.

That was my knock on Marta when I was in Atlanta in the late 90’s. I wanted to take Marta, but it took me as long to drive to a Marta park and ride station as it did to drive to work. So I saved myself the time of the Marta ride each way.

The 1920s newly built streetcar suburbs in Cleveland, Chicago and other cities, and the local opening up of western San Francisco by the opening of the Sunset and Twin Peaks streetcar tunnels which allowed mass development, has been echoed by the half billion blown on the Marin-Sonoma County “smart train”, which is just an excuse to develop greenfields since, there is now “nearby rail transportation”.

Rush hour yesterday, four people on the northbound train out of San Rafael. Freeway gridlocked in spite of the train. Now they are talking about putting in a dedicated bus lane on the freeway and restoring some bus lines eliminated to assure ridership for the train, which allowed overbuilding to generate riders to lesson the number of people commuting. Circular logic much?

It’s time for a massive purge of local politicians who have demonstrated that they are on the take from the construction, finance and ten market rate units built for every low income unit industry.

I don’t know, in seattle I actually use light rail, while the toll roads highways 99, 405, and 520 are all just for the convenience of the richies. 99 used to be one of the best highways for the hoi polloi to see the olympics and it was a great way to get to the airport. Not anymore. Gotta develop that waterfront! These toll roads, while convenient for the richies who drive them (and amazon of course) put large numbers of people on the other highways creating that convenience by suffering themselves. In the states we don’t do shared sacrifice.

In Santa Clara county in California where I live a very expensive light rail system was built that has never lived up to its billing. Despite thousands of housing units built along the rail lines few people ride them. The biggest complaint of those living in the new housing developments is the shortage of parking spaces for the motor vehicles. Recently, there was a mass killing at one of the light rail yards resulting in the entire light rail system being shutdown with no date for return to service. And to think that the local taxpayers agreed to sharp increases in taxes to pay for the massive boondoggle is very troubling.

I think the attraction of light rail is that there’s a class disdain of buses. From the examples of developing (or recently developed) economies, I see bus rapid transit systems with frequent service and interconnects, then put in a subway or light rail line as capacity, funding, and politics allow.

In particular, traffic and air pollution become intolerable, even for the elites.

Hoodlums on the buses with no ability to ban them from ridership is the problem, especially when you have locally elected D.A.s who practice “restorative justice”, a.k.a. criminals who are not even prosecuted.

One un-prosecuted bum, arrested multiple times, but thanks to Kamala Harris who pretended to be the D.A. and never prosecuted him, terrorized the busline that my daughter once rode to school in San Francisco, meaning that I quit my job to drive her twice a day.

If mass incarceration worked America would be a crime-free paradise. So-called “restorative justice” doesn’t work either because it doesn’t address the root issue.

Why do countries with high levels of “economic freedom” like the US and the UK have problems with hoodlums on buses and unsafe neighborhoods? Might be worth looking into.

Hoodlums on buses is not a significant UK problem, unless you mean pensioners and their take no prisoners wielding of their shopping trolleys. At least, in Southern England. I cannot speak of the North.

The problems on UK buses are rowdy schoolchildren (but they are only bullying each other) and, after chucking out time, drunken people fighting, throwing up or, worst, eating noisome fast food.

Cali spent oodles of money in the 1970’s to make sure that there were emergency phones on the freeway, and about the same time erected large electronic message boards, neither of which are around all that much today, nor needed.

Sorry I am a big fan of emergency phones, and cell phones didn’t get a big following until the very late 1990s, so they had a good 20 years of being a valuable public service. One of my pet peeves is the removal of pay phones in airports. I can see not putting them in new terminals, or only one per terminal, but removing them? What are foreign arrivals who haven’t yet gotten a local temp phone to do? Or what if you forgot to turn it off during the flight despite flight attendant lecturing and your battery got drained (cell phones go into max power use when trying to reach a cell tower and none can be found)?

They made sense circa 1974, but nobody saw mobile phones coming on the horizon. About the only time the message boards are utilized currently is for an amber alert.

I like pay phones too, we have 3 of them in Mineral King and 75 Cents will allow you to make a 3 minute call just about anywhere in the US, but be careful trying to make a call using a credit card, that’s where the gouge comes in. One time coming off a week long backpack trip where I had no coins, the tariff was $31 for a 3 minute call, ouch!

No different really than 1824 when building canals were all the rage, they couldn’t see that railroads would make them obsolete.

Replying to Wukchumni (putting the link in as my comments are always snagged by the site bot and disassociated spatially from the original post).

Canal barges were towed by mules or horses so of course moved slowly compared even to the first rail lines moving at about 15 to 20 mph.

And yet today barge traffic on the Mississippi, the Ohio and the St. Lawrence Seaway is a major component of trade for many commodities.

Of course the technology of motorized barges moving on waterways did not come about until after1840; but I wonder if something was lost in giving up on inland waterways. At least, I guess in the idyllic sense of having a way of cruising around on quiet, picturesque byways. But I guess, that’s a picture for an unwritten novel.

I am also a big fan of emergency phones along highways. Even today not everyone has a cellphone. Some cellphones malfunction at the very worst time.

I also miss pay phones. They have completely disappeared in my area of the world. As has been pointed out, not everyone has a cellphone, and even for those who do, there are times when they don’t work. Pay phones fill a void. I’d like to see them come back.

Yves

Re. ‘show me where the terminus is’

How about if the high speed rail terminus is the airport? Many flights might be unnecessary if you could fly into LAX and connect right there to an HSR to Las Vegas, or Phoenix, or other southwest cities. Most people don’t live downtown, so a city center terminus isn’t necessarily an advantage. There is an HSR station at Frankfurt/Main with many international routes.

You then have to substantially redo the airport, for starters.

And most cities have their terminals way spread out.

The problem is how you then get to downtown.

Many US cities have crap public transit connections from the airport to the city. Fuggedaboudit for NY, LA, and Dallas. And if you are going home, that = taxi.

There is a key problem with public infrastructure, in that nobody has ever come up with a good way to price it. Much of the problem comes down to benefits being incommensurable (such things as regional balancing, social/environmental benefits, etc), and to the difficulty in applying discount rates, especially for very long lived infrastructure. We are still getting benefits from canals and railways built in the 18th and 19th Century, but there is no reasonable means of calculating these. China as we know it wouldn’t exist without a millennium of flood control engineering. Its also very difficult to balance up risk when assessing projects, especially long tailed risks (this is particularly important when trying to assess alternatives for making infrastructure more resilient).

Economists of course have an answer – cost benefit analysis and free market pricing. Both, we know are useless, books can be written about it. The problem is that in rejecting it we have to have a realistic alternative. And nobody so far as I know has come up with an internally consistent, intellectually satisfying one.

So this brings us all to politics. The incredible messiness of the Swiss system of deciding on infrastructure spending (vote on it) is probably not replicable elsewhere, but it does work. The French of course go all out technocratic, and that usually works pretty well too, although possibly because its balanced out by a very vigorous system of local power, where mega projects get balanced out with local spending. The Germans get it right at a regional scale, but are hopeless at a national scale. South Korea was very focused on systematic infrastructure planning, but they seem to have problems maintaining focus in a more openly democratic system (unlike in the 1960’s, the President now can’t just declare that his home village is now a major industrial city and then make it happen). The Japanese got things right, up until they got addicted to pouring concrete everywhere and then it all went very wrong. The Chinese are aware of the Japanese mistake, but seem to be falling into the same trap, as they are now building HSR’s where they have no logic whatever.

If there is anyone to copy, its probably the Dutch, who have to get infrastructure planning exactly right, or they end up swimming to Germany. They also happen to have half a millennium or so of experience at it. They have a bewildering multi level system of national, regional and local plans, all subject to seemingly endless polite arguing. Somehow, out of all that, they usually get things right.

Governments are not private businesses. Infrastructure projects don’t need to “pay for themselves” or “turn a profit” through tolls or tax revenues. The purpose of infrastructure spending is economic stimulus, period. If anything of lasting value gets built like rural electrification or national parks, that’s just a bonus. The “infrastructure” project could be moving a pile of rocks a mile down the road (and then moving them back next year) and it still accomplishes the purpose of stimulating the economy. Unlike other forms of stimulus (like stimulus checks), there is no chance the money will spent on things that don’t stimulate the economy like being stuffed in a savings account or gambled on the stock market.

That doesn’t help the real-world economy, just the fake abstractions of accountants. Better to just give people money (such as UBI) to spend on things they want, leading to increased production of tangible items. Real economic stimulus needs to result in increasing production of real wealth.

Sorry for being so negative, but this piece did spin me up. Anyway, the water issue is a problem with over use. Don’t blame the dams. These dams transformed the energy system in America, particularly in the backwards, rural northwest and southeast. The private farmers need to organize and impose limits on water use. Of course they probably won’t. Same problem in Texas, only even worse. So the government will have to impose limits, I suppose. Under FDR public spending created the product (electricity) and created the demand for the product (farmers buying efficient machinery). FDR initially injected money into the banking system, which did not work. He finally learned it was up to the government to spend the money directly. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation financed it all. It became the largest central bank in the world. It not only financed the New Deal programs it financed WWII. Dirty secret: the RFC did a majority of its financing by creating new money, not issuing debt (although some debt was used, war bonds etc.) Anyway, once all the war spending was over Congress killed the RFC which made a profit of over $50 million (billion?) I cannot recall. The problem was private banks could not compete with the RFC, so they killed it.

In the Twin Cities in Minnesota we are building a SW light rail connecting the wealthiest suburbs to city center, to go with our Blue Line connecting downtown Minneapolis and St Paul, and Green Line connecting Minneapolis and St Paul. At 14.5 miles the projected cost is 2.003 billion but is starting to look more like 3+, and years behind schedule. Something about tunneling under the luxury condos on Lake Bde Maka Ska formerly known as Calhoun. That is $141 million per mile projected. Much of the area of course was a spider’s web of trolley lines until the 50’s, when that all got ripped up for roads and busses.

I have assumed for the decade plus they have been talking about this infrastructure deal that that was ample time to line up the stupid money, doubling down on doomed. With Biden needing Republican consent, I take it for granted it will be mostly graft, doing what graft has always done on infrastructure. Not that a Dem alone bill would be any less grafty.

Now if by infrastructure they meant breaking up the holdings of Big Ag to hand out to a new generation of Homesteaders with the means and ways of getting product to market, plus returning the productive capacity of America to capacity, then I would be like, go America. But I am assuming again, this is just another means for Private Equity to bank, at the expense of every last thing.

Let’s not forget the Mario M. Cuomo Bridge, where the financing was put together with tape and string, resulting in predictable cost overruns. Hopefully, we won’t find the bridge itself was also constructed on misrepresentations – see https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/mario-cuomo-bridge-structural-problems-covered-up-15594755.php

Is that the same bridge that Andrew Cuomo intervened to ensure there would be no rail line on that bridge and that any later retrofitting to add such a rail line would be impossible?

That’s great to hear. I used to be terrified driving over the old bridge, and was relieved when the new one opened. Nowhere in that article does it say anything about a systemic plan to check the bolts which made it to the finished bridge, and replace any needed.

Isn’t what is described here partly a made in America problem, due to an aversion to public planning and to relying on government subsidization of private sector projects? Europe, Japan, China haven’t had huge problems developing high speed rail and in Europe many railways were built as national infrastructure by governments. Perhaps the illusion of wide open space and endless resources fed into the American mentality, whereas more crowded and resource constrained countries tend to develop different mentalities.

Timing played a huge role. As Yves wrote in her intro, had the USA invested in high speed rail after WWII it would have been much easier to build than it is now, after 70 years of suburban groaf.

Europe and Japan having been bombed out left plenty of room for modern infrastructure development.

The government could have used its equity ownership and control of the banks to provide credit and credit card services as the “public option.” Credit is a form of infrastructure, and such public investment is what enabled the United States to undersell foreign economies in the 19th and 20th centuries despite its high wage levels and social spending programs. As Simon Patten, the first economics professor at the nation’s first business school (the Wharton School) explained, public infrastructure investment is a “fourth factor of production.” It takes its return not in the form of profits, but in the degree to which it lowers the economy’s cost of doing business and living. Public investment does not need to generate profits or pay high salaries, bonuses and stock options, or operate via offshore banking centers.

Ah, “public” infrastructure, how do I fleece thee? Let me count the ways:

Jomo Kwame Sundaram: Public-Private Partnerships Fad Fails (NC Mar 2019)

PPPs are essentially long-term contracts, underwritten by government guarantees, with which the private sector builds (and sometimes runs) major infrastructure projects or services traditionally provided by the state.

$ ‘Blended finance’, export financing and new supposed aid arrangements have become means for f̶o̶r̶e̶i̶g̶n̶ ̶g̶o̶v̶e̶r̶n̶m̶e̶n̶t̶s̶ ̶ [China, and sometimes others now and then] to s̶u̶p̶p̶o̶r̶t̶ [subsidize] powerful corporations bidding for PPP contracts abroad.

$$ The government has to fork out upfront fees, typically into millions, to gather a transaction advisory team (I.e. legal, technical, financial etc) to write out the terms of reference to guide the bidding process and to assist in bid evaluation.

$$$ Generous host government incentives and other privileges often undermine the state’s obligation to regulate in the public interest.

$$$$ PPPs can limit government capacity to enact new legislation and other policies – such as strengthened environmental or social regulations – that might adversely affect or constrain investor interests.

[I am shocked, shocked]

$$$$$ PPPs often increase fees or charges for users.

[And, wait for it….]

$$$$$$ The government may be required to step in to assume costs and liabilities if things go wrong.

Wolf Street takes it from there:

$$$$$$$$ The ultimate irony is that some of the same banks that feasted on the absurdly high interest rates the UK government agreed to pay on its PFI deals are now themselves, thanks to Carillion’s and Interserve’s collapse, public service providers.

[This last one is on the foily side, but darkly amusing and in America, the land of Second Acts, all too readily imaginable – from the comments:]

$$$$$$$$ Big banks can’t run themselves, so it is highly unlikely they can “fix” failed businesses…. In administration, the banks cannot bid and the administrator must sell at the best price. And who is best positioned would buy a defunct business? The previous owners of course.

For renewables and “cleantech”: lather, rinse, repeat.

The keys go up an’ down. The music goes roun’ an’ roun’ an’ it comes out…. here!

I saw an example of when the private sector goes it mostly alone. So a tunnel was built going to Brisbane Airport and the deal was put together by Macquarie Bank & Deutsche Bank and their financial projection that they used was that 60,000 drivers would be using that tunnel each and every day. When it opened only about 20,000 drivers used it daily. It was a fiasco. The builder lost a billion, the investors lost $1.2 billion, and the bankers lost between $1 billion and $2 billion causing the consortium to go bust. And this is why private corporations need government partnerships for – to have taxpayers eat all the losses.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-02-20/brisbanes-airport-link-3-billion-debt-a-fiasco/4529088

Give us this day our daily deal flow, mate.

Excel (hell, I remember 123) was the business equivalent of issuing suitcase nukes to the grunt infantry. Easiest thing in the world for bright young spreadsheet monkeys named Woody, Sharon and (increasingly) Prabaljeet to nudge the edge scenario into the base case. Who’s gonna notice? and it hits the hurdles. Come on man, field of dreams. Build it and….

Anyway, everyone with a hand on the elephant wants to Do Deals. Being That One Guy (usually an actual engineer or scientist) coming up with all kinds of makes-my-head-hurt-hey-look-at-me-I-was-paying-attention-in-stats-class reasons for NOT doing Deals is poison for the resume, and for the bonus pool. Ask Cassandra what the payout was for knowing the truth.

By the time the Big Deal shizzles the bed in 5-7 years time, Woody is already MD at a different bank, while Jeet has a startup doing series F.

The ambitious segment of the PMC breathes, eats and cr@ps out Change. Lean in, fail forward (on someone else’s dime). There’s no money or advancement in stability.

[OK, I’ve bagged my snark limit for the day]

You did a good job with your snark. :)

I am old enough to remember when Interstate 80 opened in Pennsylvania. At last, there was a toll-free alternative to the Pennsylvania Turnpike. And Pennsylvanians voted with their cars. I don’t think the Turnpike’s business ever recovered.

The alternative is not spending on infrastructure. Better?

A personal favorite of mine has been the Las Vegas monorail. Planning ahead the geniuses did not carry it thru to the LV airport. Oh and it’s just on the one side of the Strip. I found useful if I was staying at Harrah’s. But I’ve not gone to Vegas since 2009. So this might be a stale example.

Now LAS has a short HYPErloop!

If this is anything like Lisbon, the taxi drivers would have lobbied against it to going to the airport. There’s probably a grift somewhere.

This is the part I thought was most important:

“The real problems arose before anyone lifted a shovel of earth or raised a hammer. These problems stem from how hard it is to think ahead, and they are easy to ignore in the face of excitement about new spending, new construction and increased employment.”

Why is it hard to “think ahead”? This is what gets in my way:

a. Poor grasp of technology trend lines. When will emergent techs actually emerge? Did you see electric cars coming? I didn’t. I knew it was possible, understood advantages, but never expected it to change the industry that fast

b. Poor grasp of environmental (commercial and natural) trend lines. Covid (unexpected big externality) accelerated work from home. Did you see that coming? I didn’t. WFH may obsolete some big “infrastucture”. Quick! Let’s build some more roads.

c. Inertia. Just because something’s possible, and may be beneficial, that doesn’t at all mean it’s going to happen. To the degree new methods upset my apple-cart, uptake is severely hampered.

=====

PK’s remarks above offer up some clues; he seems to advocate for more bottom-up than top-down guidance for making the big investments. It’s a question of “agency” – who has the decision-making power .. and the resources? The “many permutations of solution” strategy .vs. the Big Bang.

So the “who does the investing?” is one question.

But there’s still the high-level policy goal problem: “is this the infrastructure we’re actually going to need in 30-50 years?”

This is especially relevant now, because of all the fundamental change at our doorstep.

That change looks like it’s going to rapidly obsolete some big components of our economic physical plant. Ag, transportation, energy, manufacturing, housing.

Where we live, what we do for a living, what resources are available to meet needs. All up for grabs.

Care to share any timely tips on predicting the future?

Thanks for this post. Reminded me of a book I read recently about the construction of the Metrodome in Minneapolis, published around the time of its construction in 1982 (and incidentally written by Amy Klobuchar long before she was a senator). Like many other stadium proposals elsewhere it was not popular at all among the public, but both teams (especially the Vikings) made lots of noises about leaving if the old Met stadium wasn’t replaced. Once it was approved, it was built as a stadium for both football and baseball because city officials found that the only stadiums that came close to breaking even were ones that could house multiple sports.

The Dome is an interesting case study to me because while it was obviously expensive, it actually came in under budget, which as you point out is quite rare. One reason is it was built without many of the high-end amenities that are now considered “standard” in new stadiums. One person involved with the project said it was built “get fans in, let ’em see a game, and let ’em go home.” Fast forward to now and the Twins and Vikings each have their own single-sport stadiums, and each has no shortage of luxury boxes, gourmet food, etc.

None of this is to say the Metrodome was a sound idea or a good use of state resources, though I can’t help but be nostalgic for the place. It simply suggests to me that the economics of these stadiums have only gotten worse as owners try to lavish increasing luxuries on the dwindling number of people who can afford tickets.

A resiliant proponent of high speed rail weighing in respectfully to this comment:

First off, I’m a lay person looking at the situation with rail lines across the southern half of Michigan where I live (Detroit, Lansing, Kalamazoo, Muskegon, Grand Rapids, other metro areas), and how that connects to Chicago. I don’t have an engineering proposal and can’t draw one up regarding “how much . . . [someone would have to] buy up and tear down.” I can say the rail yards in all of the cities listed are extensive, indeed the rail yards are beyond that in Chicago and around O’Hare airport. There they are yuuuge. And yes there is a direct line of rail from point to point =Metropolitan Airport in Detroit on the north side of the airport to the south side of O’Hare in Chicago.

So the right-of-way connecting all major urban areas, as far as I’ve investigated, is already there. Space for passenger terminals is there too. Admittedly some repurposing of the land may be necessary.

Well this has been an energy drain, so I’ll wrap it up.

Deployment of rapid rail as a means for future passenger transport is possible, indeed desirable. Development of land to accommodate passenger terminals is to be expected. There is not much undeveloped land left. I’m not sure why that should be a barrier. Renegotiating right-of-ways would be needed through Chicago as freight carriers are now deliberately holding up Amtrak trains as part of a political ax grinding venture. And just to go a wee bit further down the road of repurposing, it can be done in a just and fair manner, particularly where residential moves are concerned.

Finally, if we don’t move to rapid rail, how will large numbers of people now using individual modes of transport, find modes that are ecologically, environmentally sound?

Buses? Jets?

Right now the spending seems to be focused on repair/renewal. Roads, bridges, water systems, airports, environmental reclamation, etc. And the human infrastructure (my fave, which will pay off nicely). Before we foolishly head off in an impossible direction, causing more CO2 and other pollution; before we create not just some new “stranded” industries that don’t have a chance in a low CO2 world, but possibly even an entire stranded economy, we should look at our current maintenance schedule. It’s became a huge expense because we neglected it for decades. But maintenance of the economy and timely improvements and repairs should be fairly easy to anticipate and calculate. If we just stick to our knitting and do our necessary (now urgent) repairs we’ll be OK. If we go crazy for some new space industry thing or other impossible dream, we’ll just be in a deeper hole. And if we focus on maintenance of whatever infra we have/fix then we will be better able to analyze the most logical new infra. But if we go racing off in the opposite direction we might never understand the whole natural evolution of a functioning modern society.

Good points. If we could cut the umbilical cord between”our” representatives and the military-industrial-banking complex then we could divert those wasteful funds and afford to put an Infrastructure maintenance/replacement plan into effect. As the military is one of the largest polluters and emitters of CO2, cutting their bloated budget would lower emissions and save lives (foreign& domestic) while setting us on the path to a less sociopathic society.

“It might have been helpful for builders to have had a little less faith that future technologies would correct the problems they foresaw.”

That quote pulled out of this post could serve as an epitaph for our age.

We already have considerable infrastructure that needs repair. Patterns of use, should clarify where infrastructure spending should go. We do not need new infrastructure until what we have is in better repair. There is little point in repairing infrastructure without also doing something about the many laws enabling damage to that infrastructure. I am thinking of the law raising the gross tonnage trucks are allowed to pull over our highways — a law I recall passed during the infamous Reagan years. I am thinking of the laws that enabled the proliferation of toll roads, and toll bridges.

What most worries me about this Omnibus Infrastructure Bill are its many pages of legal gobbledygook empowering much more than repair or construction of infrastructure.

This is a bizarre post. It seems to about the defeatism of hindsight. Everything we ever did has had adverse consequences so we had better do nothing! Is the author seriously arguing there should not have been a 19thC railway boom because logging was a result? Rather than arguing that reduced prices and increased mobility raised rural and urban standards of living? The problems he identifies are not intrinsic to transport, they are a result of attitudes to the environment.

As for high speed rail, there are no significant practical barriers to its adoption in the US, just political ones. Do what the Japanese did with the shinkansen and run the tracks on elevated trackbed down the central reservation of the existing roads.

And as another poster pointed out, link up the airports as “parkway” stations, where all those exurb dwellers can park and catch a train rather than a flight, hire cars, hail taxis etc. It would help if US cities also sorted out their local public transport once you got to the airport or the central station but it’s an independent problem. And the solution could be buses and also trams on rededicated freeway lanes….