Yves here. This post is consistent with my gut reaction that China’s Evergrande crisis will be a savings & loan level crisis, as opposed to a systemic event. However, thanks to the passage of time, Americans have forgotten how nasty the S&L crisis was. Citibank nearly went under, thanks to having made too many junior loans to what turned out to be “see through” commercial developments in Texas.

Similarly, the 1991-1992 recession was nasty, but banks and the economy recovered faster than most economists expected (and remember “most economists” have an optimistic bias). A big reason was that Greenspan engineered a steep yield curve by driving short rates low but not seeking to intervene in the long end. That enabled banks to rebuild their balance sheets quickly through dumb “borrow short/lend long” strategies.

The big contribution is in documenting the scary size of China’s real estate activities.

By Kenneth Rogoff, Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics at Harvard. Originally published at VoxEU

The Chinese economy was able to sharply rebound from the Covid pandemic, helping to sustain a housing boom. The country faces a multitude of challenges over the medium term, however, on top of the much more virulent Delta variant. This column argues that the footprint of China’s real estate sector has become so large – with real estate production and property services accounting for 29% of the country’s GDP – that absorbing a significant housing slowdown would significantly impact overall growth, even absent a financial crisis.

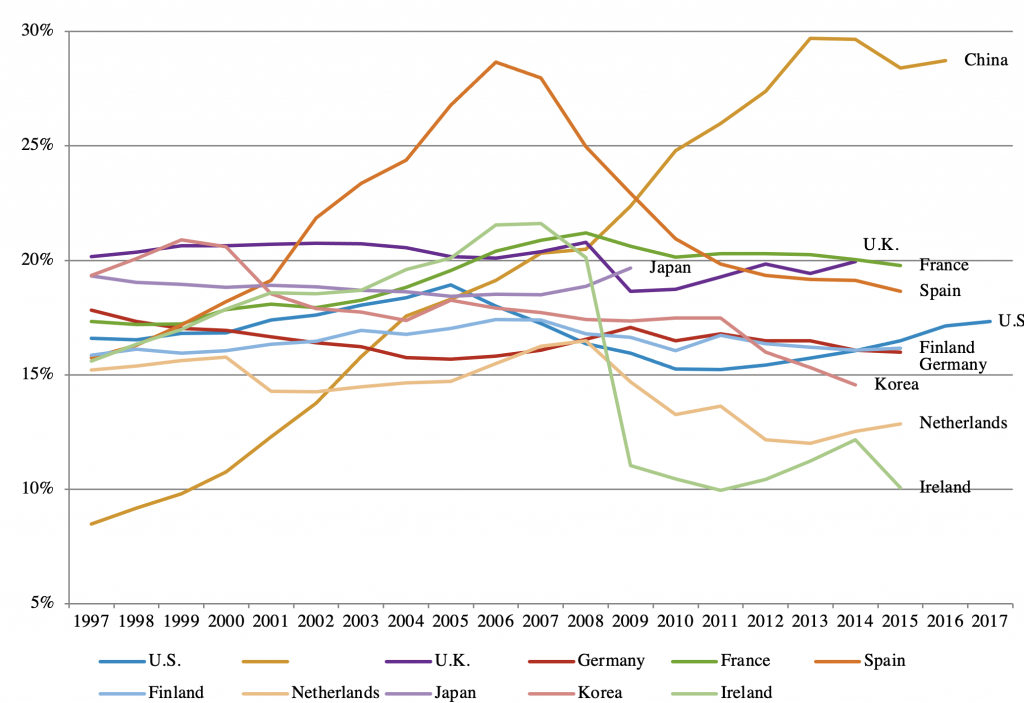

In our recent research paper (Rogoff and Yang 2021), my co-author Yuanchen Yang and I argue that the footprint of China’s real estate sector has become so large that absorbing a significant housing slowdown would significantly impact overall growth, even setting aside the usual (elsewhere) amplification effects from financial sector fragilities (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009). With real estate production and property services accounting for 29% of GDP – rivalling Ireland and Spain at their pre-financial crisis peaks – it is hard to see how a significant slowdown in the Chinese economy can be avoided even if banking problems were contained.

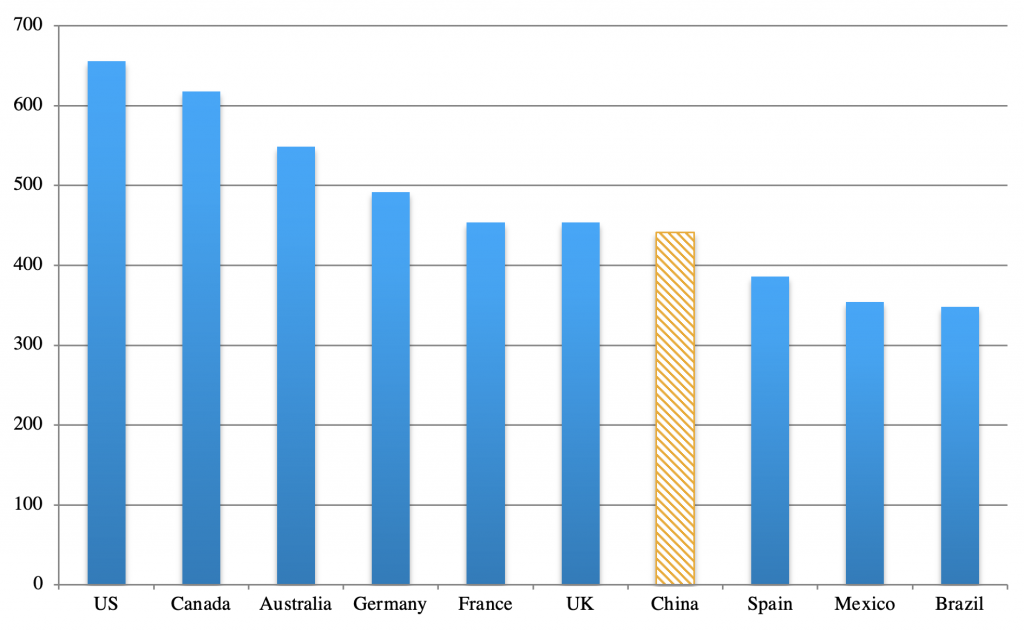

Of course, the Chinese authorities exert enormous leverage over the housing market, and have in the past used an array of tools to alternately tighten and stimulate the market. But the issue is not just maintaining stability but also maintaining the scale of production and employment. The fact that the square feet of housing per capita in China already rivals that of much richer economies such as Germany and France (see Figure 1) is sobering. Even acknowledging that the average construction quality in China is lower so that there is room to upgrade, this suggests that the current size of the real estate sector, relative to GDP, cannot easily be maintained.

Figure 1 Average residential space per person by country in 2017 (sq.ft.)

Source: Rogoff and Yang (2021).

Up until now, China seems to have brushed aside growth and real estate concerns. With its Covid-zero approach, the Chinese economy was able to sharply rebound from the pandemic, growing at over 8% in 2020 and over 12% in the first half of 2021. As elsewhere, housing price growth has been strong. Nevertheless, as China adjusts to dealing with the much more virulent Delta strain, growth is slowing sharply. Over the medium term, China faces a multitude of challenges, ranging from extremely adverse demographics to slowing productivity, not to mention environmental degradation, water shortages, and dealing with inequality. Until now, the housing boom has been sustained by a broad economic boom that now faces steep headwinds.

To arrive at our 29% estimate for the share of China’s real estate sector, broadly construed to include both physical construction and property related services, we make use of China’s most recent (2017) input-output matrix (published in mid-2019), including not only first-order effects but higher-order interactions as a real estate shock reverberates throughout the economy. (Taking into account the external sector slightly lowers the share but does not fundamentally change the message.)

Figure 2 uses a similar measure to construct the share of real estate in advanced economies, and plots these alongside China. As the figure illustrates, China is even more dependent on housing construction than Ireland and Spain were prior to the global financial crisis, and far more dependent than the US was at the peak in 2005.

Figure 2 Real estate-related activities’ share of GDP by country

Note: This figure presents the share of real estate related activities in total GDP in China, U.S., U.K., Germany, France, Spain, Netherlands, Finland, Ireland, Japan, and Korea.

Source: Rogoff and Yang (2021).

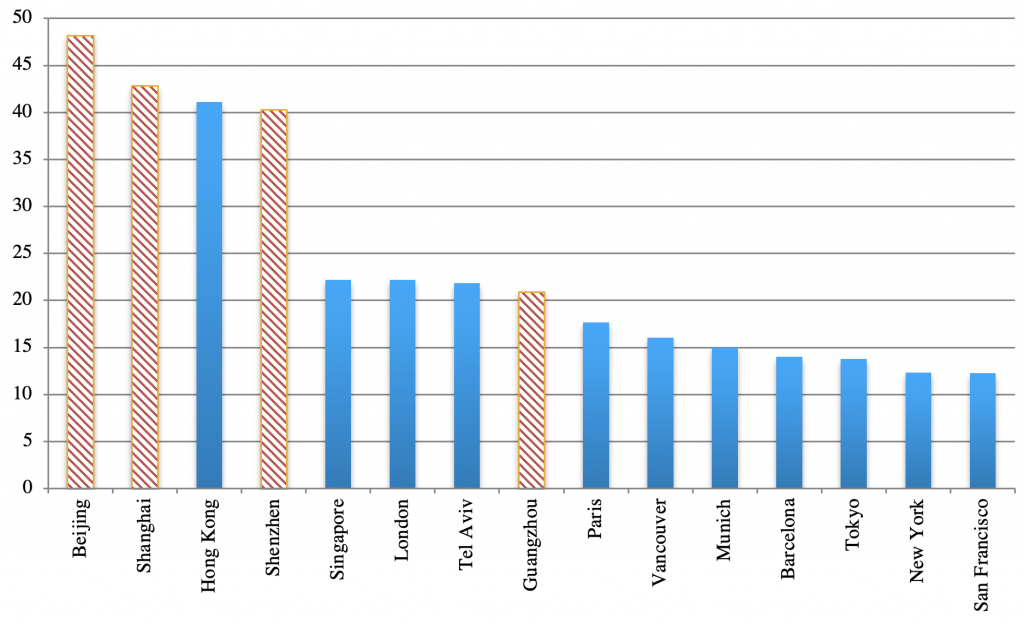

While it is important to emphasise that housing price data are difficult to collect and standardise, comparisons of China with other countries are nevertheless quite dramatic. Indeed, by international standards, the breath-taking scale of China’s real estate price boom is unprecedented for a major economy. Figure 3, based on pre-pandemic data, shows that the home price to income ratios1 in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou are comparable to any of the world’s most expensive cities. The price-to-income ratios in Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen exceed a multiple of 40, compared to 22 in London and 12 in New York.2 Of course, such price-to-income ratios might be justified if one expects China’s spectacular growth record of the past three decades to continue indefinitely. But as we have already argued, the long-term risks posed by ageing, a shrinking technological gap with the West, and a general global slowdown in productivity,make it likely that growth will continue trending downwards, even after the economy recovers from the latest wave of the pandemic.

Figure 3 Home price-to-income ratios in the world’s major cities, 2018

Note: This figure shows home price-to-income ratios in Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Singapore, Tel Aviv, Guangzhou, Paris, Vancouver, Munich, Barcelona, Tokyo, New York, and San Francisco, respectively.

Source: Rogoff and Yang (2021)

We acknowledge that a number of previous authors have explored the potential risks in China’s housing market, with leading examples including Fang et al. (2015), Chivakul et al. (2015), Glaeser et al. (2017), and Koss and Shi (2018). Although there is a range of opinion (see especially Gyourko et al. 2010), the general consensus has been that although China’s housing price appreciation is literally an order of magnitude greater than the US experienced in the run-up to its 2008 financial crisis, it is not necessarily a bubble and it would take a sharp, sustained economic slowdown in overall economic growth to generate a long-lasting housing recession.

However, these studies are based on data which are now somewhat out of date in the landscape of the rapidly evolving Chinese economy. In Rogoff and Yang (2020), we make use of newly available sources, especially taking advantage of the digitisation of China’s statistics that has helped provide both more extensive and more accurate data, to extend and significantly update the earlier work. And, of course, the Covid-19 pandemic, particularly as new mutations evolve, poses a very real risk that the catalyst for a sustained growth slowdown could be at hand.

My 2021 paper with Yang focuses on the importance of real estate for growth and employment, but of course the financial vulnerabilities are also a great concern, even if China proves much more adept at debt workouts than Western governments managed after 2008, as many observers anticipate. Nevertheless, the looming bankruptcy of the Chinese real estate developer Evergrande, with over $300 billion in debt,3 will be by far the largest the government has had to deal with, and weaker real estate firms are facing challenges rolling over their debts. Gao et al. (2020) discuss for the case of the United States in the early 2000s, housing speculation in the run-up to a crisis can considerably aggravate real effects of the eventual collapse. While the Chinese authorities have long made periodic efforts to contain speculation, this has been immensely difficult in the face its epic, decades-long housing price boom, as Wei (2017) emphasises.

The challenge of rebalancing the economy away from real estate production and services is a problem China will have to face in the coming years, perhaps sooner rather than later.

See original post for references

Michael Pettis has a very good overview on the very bad options facing Chinese regulators.

The most important aspect of this is to recognise that Evergrande is not the problem – its the symptom of the problem. The core (related) two problems in China are a gross over reliance on residential property for economic growth, and excess domestic debt. We still tend to see China as a model of a country that has grown through industrial might, but in reality for the past 10 years or more China’s growth has been a good old fashioned debt driven construction boom. As an Irish person, this is all too familiar (although of course there are massive differences in the economy). I’m sure Ignacio will recognise this too. Older Japanese will know exactly what it looks like and what happens if governments just try to roll over debt without dealing with the deeper structural issues.

While this article and the Pettis article focus on the financial engineering side of this, there is also an important demographic and structural element. Quite simply, China has overbuilt houses and it is overbuilding infrastructure, so there is no simple ‘just get rid of the debt, give the houses to the homeless and employ everyone building nice things’ way out of this either. In a housing slowdown, tens of millions of Chinese will become unemployed in a country with very weak unemployment protection, and no safety valve in the form of emigration (which partially saved Ireland and Spain 10 years ago).

The obvious solution is to rebalance the economy by encouraging more consumer spending – i.e. more income to regular people, stronger unemployment benefits, and decent pensions to stop making people think their only form of security in old age is owning more apartments. But the evidence from the Covid response is that the Chinese are naturally very cautious consumers (for very good historical reasons), and its not clear that this can be changed in the short to medium term. In other words, giving people cash to spend directly or indirectly might not work – they might just sit on it, or salt it away out of the country to perceived safer havens.

Another core problem the regulators will have to face is that the people who have benefited most from the policies are also very powerful and very influential. Its been very clear that the most senior Chinese officials (including Xi himself) know what the problems are, and they know the things that need to be done. But despite grand statements over the past few years, they have done precisely nothing to follow up their fine words. That indicates that it may simply not be possible politically to do what is needed. Even the most autocratic states have to deal with interest groups carefully, especially when those interest groups are tightly bound up with the ruling elites. We’ve already seen this in the way Evergrandes senior people have been untouched in comparison to the way the tech outsiders were publicly brought to heel.

So yes, China will almost certainly manage Evergrande reasonably well and its unlikely they will mishandle things to the extent of allowing a financial contagion to take hold. But the problems are deep and systemic and the temptation to just put sticking plaster on and pretend there is nothing really wrong will be very strong. The real danger to China is a Japanese style stagnation lasting a decade or more.

Thanks for this comment. Encouraging more consumer spending to rebalance the economy is a sensible goal. I wonder how high avg. household debt is in China – all those loans to buy flats, etc – and how much headwind that creates to increasing consumer spending.

Traditionally, household debt has been very low in China, but its surged enormously in the past few years thanks to a huge expansion in mortgages and personal debt instruments. By some measurements, its now significantly higher than in the US (when measured as a percentage of household income). I suspect official figures are an undercount – as one Chinese friend said to me ‘In my village, everyone owns money to everyone else’. Off the books loans are very common so far as I can see and are almost entirely invisible to official figures.

I think its a huge potential headwind. Because of poor pension rights and a very inadequate safety net, Chinese consumers are very reluctant to spend, even when given money if they are feeling uncertain. So a simple boost to household incomes to make up for any rebalancing may not be enough. For years the CCP have been talking up rebalancing and boosting peoples incomes, but have never followed through in any meaningful way.

It must also be realised that a huge amount of spending is done by local governments in China, and they are very heavily dependent on land sales for income. A housing crash will have devastating impacts on their finances, so thats another area that would need to be propped up.

So even though in theory a fiscal boost could help a lot, in practice any spending would probably have to be done by the government. Unfortunately, they’ve only developed a talent for doing things that require covering everything in concrete. China is looking more and more like mid 1980’s Japan.

I should say something about the idea of “overbuilt” housing.

First, China has something of a mismatch — too much in some rural areas, but still a need in larger areas.

Second, much housing the is 30 years old or more is really badly constructed. Chunks of concrete falling off. Bad plumbing that needs to be replaced.

You may remember jokes about cheap and shoddy Chinese manufactures that were coming into the US and Europe 30 years ago. Well,much housing construction was in the same category. So whereas here in New York, you will pay MORE for an old building because it is better constructed, the opposite is true in China. So there will be substantial rebuilding and retrofitting.

Its a few years since I was in China, but as per usual when I travel I like to poke around construction sites and buildings that are accessible. On my first visit in the 1990’s I had the usual traveller experience of going to my nice looking hotel bathroom and finding the faux gold faucet come off in my hand. Fortunately it wasn’t plumbed correctly either so there wasn’t enough water to cause a flood. I’ve been to Mao era hotels which were, on the other hand, plain but quite impressive.

Things have certainly improved a lot, but I’ve seen enough of some of the outer speculative housing built (at least in the Tier II and II cities) to see that its largely unrecoverable. I’ve seen better built film sets. But some housing is pretty good and plenty of the blocks have sufficient size and good structure that they can provide a long life with the correct retrofitting. My last visit was to Shanghai and some of the newer buildings there are very impressive, although I’d worry about some basic things, like concrete quality – I’ve seen spalling in every very expensive and upmarket buildings (plus engineering structures) that if I saw them in my city, I’d be warning buyers off until they got a full engineering report. Specialists I’ve talked to have told me that the big weakness in the Chinese construction engineering industry is concrete standards and controls, thats what would worry them if advising buyers.

> . . . the big weakness in the Chinese construction engineering industry is concrete standards and controls . . .

I would have thought they were experts in pouring concrete by now, yet moar practice is required. CO2 to the moon.

I wonder if a dramatic expansion in military spending and associated tech might be the line of least resistance?

They have certainly noticed the US’s idea of strategic competition looks a bit threatening?

Thank you for the Pettis view. Now I will now turn my jaundiced eye to the Rogoff view, with the proviso that some anonymous UMass Amherst grad student may not have analyzed his data sets. ;-)

Pettis has been talking about China needing to up its consumer spending for decade at least now, and sees it as the major obstacle of getting out of the middle-income trap. The Chinese govt always makes the noises around it, but so far nothing much specific (that I can remember) – except the moves against the super-rich, but those aren’t really about upping the wide consumption/income.

We’ll see how this goes.

I just hope his calculations were not done in Excel

Lol. Thanks.

I wonder if China will prosecute bad actors. It seems necessary for Xi to fully lay the blame at others while inflicting economic harm to a wide swath of the population.

So far, it seems there is a fundamental difference between these property firms and the tech firms. People like Jack Ma were uppity outsiders, who could be taken down to send a message. The senior people in Evergrande has so far been conspicuous by their absence from much condemnation. This strongly suggests that they are ‘insiders’ and as such are unlikely to be made responsible – or possibly that they know where too many bodies are buried. This is quite predictable as the property industry in China is very tightly woven in with government power at multiple levels.

There will of course be a few scapegoats, but its questionable whether they will be the real perpetrators.

Depends on what you mean by senior.

Six senior Evergrande executives are facing “severe punishment” for securing early redemptions for themselves on investment products which the imploding Chinese real estate giant told retail investors they couldn’t repay on time.

According to the Financial Times, over 40 group executives had personally invested in its investment products – with six of them securing early redemptions. All six will return the money.

“All funds redeemed by the managers must be returned and severe penalties will be imposed,” said the company, which has offered to repay investors with discounted apartments and parking lots.

That reads as if Evergrande management are acting as the financial regulator and judicial authority when it comes to investigations of wrongdoings. Which is quite possibly true.

My interpretation of the Evergrande collapse is:

a. The Chinese have known for decades about this RE problem. Think of all the articles by Pettis, Bass, DeLong, etc. about the property speculation, over-building, and debt-fueled growth you’ve read. That theme has been building, and is well-documented for what…two decades? This is a well-known problem

b. China used the real estate mechanism to good effect; they built a lot of housing for a lot of people, and it provided a lot of good jobs, and it was the consumption engine that enabled the buildout of lots of industrial capacity (steel, concrete, etc)

c. China has already demonstrated that it doesn’t want to become a speculation-driven, too-big-to-fail captured economy. “housing is for living in, not speculating upon” is the stated policy.

d. The interior of Asia is now opening up for development. The exit of the U.S. from Afghanistan and the concurrent flurry of new admissions/interest in the SCO, BRI, etc. indicates that trade relationships are now possible which heretofore have been much more risky. The political and economic landscape of the Asian interior, and the western transit-points into Africa, SW Asia, and up into the EC have all changed, and are continuing to change rapidly

e. China has shown that they want to be a trading and manufacturing and innovating economy; they want to grow by building wealth .vs. extracting wealth

With all that in mind, what I see is China winding down a phase of economic development, curtailing speculation, reducing the need to create additional debt to service and support an overhang of already-bad debt. This is good econ policy. We may see China do what we in the U.S. didn’t do during our 2008 RE-induced debacle.

The big question for me is “what to rotate investment into”. I don’t see China moving too heavily into consumer-driven investment. I see them investing in more innovation and the resulting new industries, and spinning up the Asia-interior investment and build-out.

The steel and concrete will get re-directed into overland transport infrastructure, new regional distribution, materials, and manufacturing centers distributed across the western hinterland, and quite possibly some very different settlement pattern architecture that more accurately responds to fundamental trends in the environment, such as evolving toward a cyclical economy less dependent on major energy and materials withdrawals from the natural world.

That last point may be projection on my part, but China is an innovator, and one great field of innovation is in the realm of settlement patterns and distributed ag, manufacturing, energy and major changes in housing architecture and materials.

I agree with PK’s assessment of the political need to keep the major players on-side, but these same major players are party to the 5-year econ plans – they are at the table as those plans are written, so they know what the underlying trends are. The political deal-dialog will be “exit that sector, enter this sector, here’s where to invest”

It appears to me, from my remove, that China functions mostly by high-level party consensus. They know what they have to do, and why.

This could be a major turning point, not just for China. If China succeeds in executing this policy evolution, and I think they will, then this signals an epochal change in state-of-the-art economic and political operations at the national level. Others will notice.

There is NO need for construction activity to slow simply because Evergrande went under. It has left a residue of many unfinished buildings. No doubt these WILL be completed, and more building will take place, so as to lower China’s house-price/income ratio.

Wiping out Evergrande’s bond and stockholders need not affect its physical housing. The debts will be wiped out, and on the other side of the balance sheet, the savings of wealthy Westerners and Chinese. So wealth distribution will become less extreme. For Chinese buyers who have made down payments, they will still take possession of their homes when these are built.

In sum, there is no need for an economy-wide slowdown, if handled properly. Since last October, I have been arguing this point to a very large Chinese audience.

But Bernanke and Paulson said the “western civilization will end as we know it” if we dont bail out bond holders?

Do you mean that if we didnt bail out the creditors, working stiffs like me would have had a chance to bid on a discounted or reasonably priced house for my family before BlackRock?

Why are you advocating such policies that will cause destruction of chinese civilisation? Surely you cant know better than Bernanke and paulson.

I wonder if we will see a political fight over the burden sharing? Perhaps that fight is already finished. I did note an increase in the number of times Xi wore a Mao suit.

China will be redirecting resources into “technology” because the US has demonstrated that it will no longer cooperate with Chinas development goals.

Missiles, chips, robots, AI, and renewable energy.

If evergrande built up so much debt, does that mean they sold houses for less than the cost to build them, with investors making up the difference?

If that is a widespread practice, then what happens if those investors are no longer there?

I hate to tell you but when real estate construction projects fail, the losses are often over 100%. The party that takes on the project never wants to finish someone else’s effort; among other reasons, they may not agree with the assumptions re sales prices and internal structure (mix of units, amenities). So you have to incur the costs of a teardown.

Will China (Xi) show their governance and their version of capitalism is superior by handling a sector meltdown with alacrity, equity, much less disruption of the overall economy? Or will they call on Geithner to “foam the runway” for big institutional actors while stiffing Main Street.

In my very humble opinion, one of the key weaknesses of the US arsenal for dealing with financial crisis is resistance to supporting low and moderate income citizens and throwing money at the big guys. It’s all about moral hazard, means testing, and the deserving poor here. Unspent HAMP, rental assistance sitting in state coffers, and, of course President Manchin’s benighted, entitled economic views. Thank goodness we have our financial elites “doing god’s work.”

Great opportunity for one-upmanship on management of economic crisis as Afghanistan, the MENA region and the underdeveloped world generally turn to China and away from the US. Who ya gonna call?

But we’re absolutely the best ever at blowing shit up!

It’s easy. Giving money to people who have no morals is the only assured way to prevent any moral hazard.

I’m completely baffled by a communist government that doesn’t provide it’s citizenry a safety net of unemployment & retirement. I suspect that consumer spending based upon increased income (sans debt) will not accelerate without a government guaranteed safety net for citizens. Otherwise, China will just go back to the same old growth via debt program (“unhealthy growth”).

One of todays links actually provides an excellent intellectual history of the Chinese economic/social model and suggests why social protection was never a high priority. Short version is that the focus of Chinese socialism is at root one of economic development and popular (State) control over production, rather than a vision of protecting people from cradle to grave. In the pre-1980’s there was of course lots of public housing and the ‘iron rice bowl’, but the failure to build in a proper replacement system when it opened up to free markets and trade has left China with an appalling health system, a barely functional social protection system, an uber competitive education sector and a rickety pension fund. They’ve covered all this up by providing economic growth and plenty of jobs and a bigger pie for everyone. This is why they are so worried about a drop in economic growth – there is no fallback.

The big irony is that Taiwan, home of the capitalist losers of the revolution (KMT), has ended up with a far better health and social provision system than their nominally communist counterparts.

Salary levels are low in Taiwan though. Resident Foreigners, Taiwanese, they all complain about this situation. Real estate prices though? Sky high. Mortgage debt makes up a huge proportion of household debt in Taiwan.

When I think of Taiwan, I think of the US except the former has a single payer healthcare system and high speed rail.

Your link is broken.

Chinese culture has a much stronger notion of the responsibilities of the state versus the person. It’s a two-way street. When there is flooding or fires, the national (domestic) army shows up en masse to help people.

In the West we owe taxes to the king. but the king owes us nothing. Not so in Chinese culture.

The Chinese try and increase domestic consumption.

Oh dear, they are using neoclassical economics.

Davos 2019 – The Chinese have now realised high housing costs eat into consumer spending and they wanted to increase internal consumption.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MNBcIFu-_V0

They let real estate rip and have now realised why that wasn’t a good idea.

The equation makes it so easy.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

The cost of living term goes up with increased housing costs.

The disposable income term goes down.

They didn’t have the equation, they used neoclassical economics.

The Chinese had to learn the hard way and it took years, but they got there in the end.