“Sleep that knits up the ravell’d sleave of care” –William Shakespeare

By Lambert Strether of Corrente

For many months I’ve been able to recall my dreams on waking, which is new for me. I remembered that strange dreams were in the second tier of some symptoms lists circulated[1] for the original Wuhan, pre-Alpha strain of Covid-19, and it crossed my mind — though not concernedly enough for me to get a test to see if I am seropositive — that at some point I’d had an asymptomatic case (infection anecdotes; post-vaccination anecdotes). It then occurred to me that we’ve never run a post on Covid and sleep, so here we are.

Through a natural association, I had “sleep” filed along with “sex” and “death” as things we don’t understand, recalling Michael Brook’s book, 13 Things That Don’t Make Sense, which has them each as one of those things. Brooks did not, in fact, include sleep, but he might as well have. From Neuroscience in 2001:

Sleep (or at least a physiological period of quiescence) is a highly conserved behavior that occurs in animals ranging from fruit flies to humans. This prevalence not withstanding, why we sleep is not well understood.

And from the Sleep Foundation, twenty years later:

Even after decades of research, the exact reason why we sleep remains one of the most enduring and intriguing mysteries in health science.

As a sidebar, the fact that we don’t understand many of the most important things in life might lead one to question the universality of the meritocratic ideal, given that advancement within a meritocracy is driven by what can be known, not by what is not known, or not knowable. End sidebar.

We do know that being deprived of sleep is bad. From the American Psychological Association:

Decades of research have linked chronic sleep deprivation to an increased risk for obesity, heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, and problems with immune function (“Sleep and Sleep Disorders,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Sleeping more or less than recommended—typically 7 to 9 hours a night—is a significant predictor of death by any cause (Cappuccio, F. P., et al., Sleep, Vol. 33, No. 5, 2010). Sleep disturbances also hinder social, motor, and cognitive skills and predict suicide risk, depression, and other mental health problems (Bernert, R. A., et al., Current Psychiatry Reports, Vol. 17, 2015; Fang, Y., et al., npj Digital Medicine, Vol. 4, 2021; “Mental health and sleep,” Sleep Foundation).

We also know that much of the world had been deprived of sleep, before the current Covid-19 pandemic. From Sleep:

There is growing evidence, mostly from populations in Western countries, pointing to downward trends in the average duration of sleep and increasingly higher prevalence of insomnia and other sleep disturbances. For example, data from nationwide surveys in Canada and the United States indicate that more than 20% of the general adult population suffer from insomnia, and this number is likely to increase over the next few decades. These percentages are consistent with prevalence figures of short sleep duration reported in population-based studies across different Western countries over the past 3 decades. More broadly, problems with falling asleep or day-time sleepiness and fatigue affect even larger segments of the population, imposing a considerable burden in terms of morbid-ity and mortality outcomes, as well as substantial cost implica-tions for society in developed settings.

And that’s Western countries. In this study:

To our knowledge, this is the first report on sleep problems and associated factors in a large number of older adults across 8 populations from low-income settings in Africa and Asia. Overall, 16.6% of adults age 50 yr and older reported sleep problems in this study.

So, at least in the instance of sleep, there is no “normal” to return to; we should not assume that we’ll all get “a good night’s sleep” once Covid has been eradicated reduced to the status of a lethal disease that’s not part of the narrative.

With that, I will turn to Covid-19 and sleep. This post has no thesis. Rather, I’ve gathered a good deal of intriguing material, though not systematically enough to call this post a survey (the two fields of sleep of Covid are both huge). I hope the material has educational value in itself; it may also inform your practice in daily life. I’ve sorted the material into two buckets: The effect of SARS-COV-2, the virus, on sleeping individuals; and the effect of COVID-19, the disease, on populations. Naturally, I am not offering medical advice (or dosages, or anything like that).

SARS-COV-2 and the Sleeping Individual

Here, I will look at sleep and vaccine efficacy, circadian rhythms, and melatonin. Interestingly, the last two may involve repurposing drugs (always a plus, in my book).

Vaccine Efficacy

From The Lancet, “Could a good night’s sleep improve COVID-19 vaccine efficacy?”:

Although data from phase 3 trials indicate that factors such as age and biological sex might not be as prominent in modulating the efficacy of certain COVID-19 vaccines (eg, in case of the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine produced by Pfizer and BioNTech),2 the role of sleep in this context is unclear. As suggested by previous studies, sleep duration at the time of vaccination against viral infections can affect the immune response. For instance, 10 days after vaccination against the seasonal influenza virus (1996–97), IgG antibody titres in individuals who were immunised after four consecutive nights of sleep restricted to 4 h were less than half of those measured in individuals without such sleep deficits. Similarly, shorter actigraphy-based sleep duration was associated with a lower secondary antibody response to hepatitis B vaccination. Sleep might also boost aspects of virus-specific adaptive cellular immunity. Compared to wakefulness, sleep in the night following vaccination against hepatitis A doubled the relative proportion of virus-specific T helper cells, which are known to play a prominent role in host-protective immune responses. Interestingly, in individuals who slept the night after the first vaccination, the increase in the fraction of interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-positive immune cells at weeks 0–8 was significantly more pronounced than in those who had stayed awake on that night.

So, if your answer to the Lancet’s question is “Yes,” at the very least, sleep is an enormous confounder for all the vaccine studies, which is pretty funny when you think about it.

Circadian Rhythms

Circadian rhythms are the body’s cron jobs: They cycle through essential functions and processes. One such is the sleep-wake cycle. From the European Respiratory Journal, “Putative contributions of circadian clock and sleep in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection”

Sleep, a circadian behavioral manifestation of major regulatory homeostatic mechanisms such as those associated with immunity, has also been shown to interact with host defenses at the molecular and cellular levels. Indeed, extensive literature has indicated the important role of homeostatic sleep in innate and adaptive immunity [46]. Furthermore, there are clear reciprocal dependencies between sleep duration and quality and the immune responses against viral, bacterial, and parasitic pathogens, the latter altering in turn sleep patterns [46]. Thus, it is likely that improved sleep quality and duration in the population may mitigate the propagation and severity of disease induced by SASRS-Cov-2 infection.

It doesn’t really seem that sleep duration and quality are optimal in a hospital setting. That said, qualifications along with speculative mechanisms:

As mentioned above, it is unclear how disrupted or insufficient sleep may affect SARS-Cov2 infection rates and the severity of its clinical manifestations. Typical symptoms of acute lung injury (ALI) include dyspnea, hypoxemia and pulmonary edema which may deteriorate into the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). The cell-based pathological mechanisms of such progression involve activation of immune-inflammatory cascades resulting in disruption of the alveolar- apillary barrier. This immuno-inflammatory activation is influenced by the circadian clock, and therefore deregulation of circadian rhythms such as in night shift workers or social jetlag could play a disease-specific role by altering the susceptibility to infection or modifying the clinical manifestations of COVID-19 syndrome…. Furthermore, since ACE2, which may be regulated by clock activity, was shown to have a protective effect through suppression of apoptosis of pulmonary endothelial cells, it is possible that chronobiological interventions may mitigate the progression of lung injury, if such interventions occur in a very early stage of the infection.

At the very least, it does seem sensible to think about incorporating circadian rhythms when administering drugs. From Frontiers in Neuroscience, “COVID-19: Sleep, Circadian Rhythms and Immunity – Repurposing Drugs and Chronotherapeutics for SARS-CoV-2″:

Evidence from the literature suggests that nearly half of all physiological functions, including the body’s pathogenic response, are controlled tightly by the circadian clock. Chronotherapy exploits this rhythmic pattern to its advantage to improve the outcome of different medical interventions as discussed throughout this review. This manuscript highlights that diurnal variation exists in the functioning of our immune system, in vivo cholesterol synthesis, coagulation, fibrinolysis and blood pressure, and that considering the time of drug administration might significantly improve the treatment and management of the novel coronavirus disease-19.

The drugs discussed for repurposing include statins, blood thinners/anticoagulants, and antihypertensive drugs. The piece also references melatonin, to which we now turn.

Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone that induces sleep in humans; the brain produces it in response to darkness. (“Research suggests that melatonin plays other important roles in the body beyond sleep. However, these effects are not fully understood.”) Media interest in melatonin as a Covid treatment seems to have peaked in 2020. That said, there’s continuing investigation of repurposing it (and of course it can also help put patients to sleep, as shown in this RCT). Here is a case for melatonin, from (Elsevier, peer-reviewed) Endocrine Practice, “Melatonin for the Early Treatment of COVID-19: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence and Possible Efficacy,” in August 2021. This is a meta-study. From the Results section:

The results showed that melatonin acts to reduce reactive oxygen species–mediated damage, cytokine-induced inflammation, and lymphopenia in viral diseases similar to COVID-19.

Here are a number of speculative mechanisms (details and pathways omitted):

Viral infection with SARS-CoV-2 can cause severe inflammatory responses and oxidative stress; the use of melatonin may be able to attenuate some of these reactions…. It is thought that SARS-CoV-2 causes severe lung pathology by inducing pyroptosis, which is a highly inflammatory form of programmed cell death…. Melatonin acts as an inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome, inhibiting pyroptosis and ultimately exerting an anti-inflammatory effect… SARS-CoV-2 infection involves induction of a “cytokine storm”… Melatonin exerts anti-inflammatory effects through the reduction of proinflammatory cytokines… Furthermore, once inside the cell, SARS-CoV-2 begins its damaging oxidative effects starting with the recognition of its pathogen-associated molecular patterns by pattern recognition receptors located on host mitochondria and subsequent interaction with mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein to initiate antiviral cascades resulting in excessive ROS production… Melatonin has been shown to reduce acute lung oxidative injury by suppression of ROS.

And much more:

Given the information presented here, melatonin has plausible benefits of reducing inflammation and possibly curbing the cytokine storm caused by SARS-CoV-2. Melatonin recommended early in the course of infection could provide benefit at a relatively low cost and a tolerable safety profile.

Currently, there are no published results from a clinical trial using melatonin as a treatment for COVID-19; however, our search provided 2 protocols for double-blind, randomized clinical trials utilizing melatonin dosages of 5 mg twice a day by oral capsule for 7 days and 5 mg per kg of bodyweight intravenously every 6 hours for 7 days. In addition, the clinicaltrials.gov website currently lists 6 ongoing studies (NCT04474483, NCT04784754, NCT04409522, NCT04530539, NCT04353128, and NCT04470297) using melatonin as treatment in patients with COVID-19 in both the intensive care unit and outpatient departments. Although these studies will provide insight into the effectiveness of melatonin in COVID-19, they do not focus on starting treatment as early as the day of diagnosis. In addition, an argument has been made that the treatment of COVID-19 with melatonin can be used before clinical trials…

Melatonin is available over the counter with indications for jet lag, nicotine withdrawal, winter depression, tardive dyskinesia, chemotherapy-related thrombocytopenia, and insomnia. The side effect profile remains relatively benign… Administration for preterm infants, children, and adolescents in various diseases has shown no side effect except at high doses. Caution should be exercised in patients on multiple medications due to potential unknown interactions and in patients taking a medication that can inhibit cytochrome P450, since melatonin is mainly metabolized by this enzyme.

Those who are at highest risk for developing severe cases of COVID-19 should receive treatment as quickly as possible. The current study argues that melatonin would be a cheap, safe, and effective first-line treatment for COVID-19, especially in higher-risk populations.

Melatonin is at least worth a look (and if you know anybody who’s looking, make sure they read the text following “relatively benign”, because I had to omit detail to save space. And read the whole thing, all the way to the end).

And now from individuals, let’s turn to populations.

COVID-19 and Sleeping Populations

The Covid-19 pandemic has had massive effects on sleep patterns all over the world. From Sleep Health, “Sleeping when the world locks down: Correlates of sleep health during the COVID-19 pandemic across 59 countries“:

The outbreak of COVID-19 in December 2019 rapidly escalated into a global pandemic affecting countries around the world, which imposed social isolation measures to stop the spread of the disease. The mass (home) confinement in addition to the uncertainty of the pandemic led to drastic changes in people’s lives, affecting social interaction, work, school, physical activity, and sleep.

Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic has imposed extreme psychological stress on many individuals, the extent of which we are only just beginning to understand.More than half the sample [n=6882, online survey distributed between April 19 and May 3, 2020 ] shifted their sleep toward later bed- and wake-times, and more than a third reported increased sleep disturbances during the pandemic. Older age, being partnered, and living in a higher income country were associated with better sleep health, while a stricter level of quarantine and pandemic-related factors (being laid off from job, financial strain, or difficulties transitioning to working from home) were associated with poorer sleep health. Domestic conflict was the strongest correlate of poorer sleep health. Poorer sleep health was strongly associated with greater depression and anxiety symptoms. Participants from Latin America reported the lowest sleep health scores.

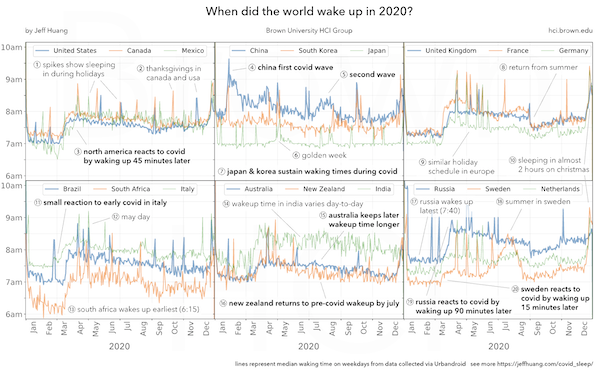

Interestingly, changes in sleep patterns differ by country:

Covid and Dreams

Perhaps I’m not the only one. From Nature and Science of Sleep, “How our Dreams Changed During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Effects and Correlates of Dream Recall Frequency – a Multinational Study on 19,355 Adults“:

Many have reported odd dreams during the pandemic.

And:

To date, only a handful of studies have investigated how the pandemic is reflected in our dreams. Previous research indicates that experiencing collective threatening situations, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, and terrorist attacks, is associated with changes in dreams and sleep patterns. This would make sense as such experiences can cause immense psychological stress, and dreaming is hypothesized to be involved in emotional processing and emotional memory consolidation.

The study focused on Dream Recall Frequency (DRF), presumably because that can be measured:

We found that there was a significant increase in DRF during the pandemic, with 9.2% reporting heightened DRF, which is in line with other reports. Participants with high DRF during the pandemic experienced more pronounced changes in sleep behavior as a consequence of the pandemic, such as worsened sleep quality and more sleep problems.

….[T[here were no differences concerning DRF between people who reported having had COVID-19 and people who had not been infected.

But I wanted to know what the dreams were about! Imagine doing a study where your subject recalled a dream, then ticking a box and not finding out what the dream was. Anyhow, here, here, and here are some anecdotal reports, all of which include swarming behavior, which is pretty darn on the nose for zeitgeist, if you ask me.

Covid and Insomnia

From Vox, “The pandemic has created a nation of insomniacs.” Americans weren’t getting a good night’s sleep to begin with, but:

In one study conducted across 49 countries in March and April 2020, 40 percent of people said their sleep was worse than before the pandemic. Participants’ use of sleeping pills increased by 20 percent. Google searches for “insomnia” also spiked in the US in April and May, when many parts of the country were under stay-at-home orders. Meanwhile, Americans’ spending on the over-the-counter sleep supplement melatonin increased by 42.6 percent [see above] in 2020. “That consumer behavior is a sign that people are struggling,” [Jennifer Martin, a clinical psychologist who serves on the board of directors for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine] said.

Then there are the hundreds of thousands of people who have contracted Covid-19. While insomnia isn’t technically considered a symptom of the disease, the respiratory symptoms can make it difficult to sleep. And clinicians are seeing a lot of chronic sleep problems in people experiencing long Covid. “We’re still trying to learn about that, and whether it might play a role in making the recovery more difficult,” Martin said.

While there’s not yet much data on sleep trends this year, experts say the sleep disturbances of the early pandemic could persist over time. For one thing, plenty of people are still dealing with a lot of anxiety around the pandemic, from those who have lost their jobs to those dealing with the stress of sending kids to school amid the delta variant. As [Lauren Hale, a professor of family, population, and preventive medicine at Stony Brook University] put it, “everybody has their own reasons why they aren’t sleeping as well during an international crisis.”

For another, any stressful experience that disrupts sleep for a period of time risks triggering chronic insomnia. When patients are asked how their sleep problems started, they’ll typically mention some “stressful event or a big change in their life as a thing that sort of got them off track,” Martin said. “Short-term insomnia is how long-term insomnia starts.” That’s one reason some Americans may still be having trouble sleeping now, more than 18 months into the pandemic, even if they’re vaccinated and their personal fears around Covid-19 have (somewhat) abated.

Of course, we can’t have the labor force interfered with that way, so we’ve invented a new buzzword: “coronasomnia.” From the BBC:

[T]he ongoing coronavirus crisis has made getting a good night’s rest significantly harder. Some experts even have a term for it: ‘coronasomnia’ or ‘Covid-somnia’.

This is the phenomenon that’s hit people all over the world as they experience insomnia linked to the stress of life during Covid-19. In the UK, an August 2020 study from the University of Southampton showed that the number of people experiencing insomnia rose from one in six to one in four, with more sleep problems in communities including mothers, essential workers and BAME groups. In China, insomnia rates rose from 14.6% to 20% during peak lockdown. An “alarming prevalence” of clinical insomnia was observed in Italy, and in Greece, nearly 40% of respondents in a May study were shown to have insomnia.

Simple, more of us are now insomniacs. With the pandemic into its second year, months of social distancing have rocked our daily routines, erased work-life boundaries and brought ongoing uncertainty into our lives – with disastrous consequences for sleep. Our health and productivity could face serious problems because of it. Yet the scale of the problem could potentially bring change, introducing new elements into how we treat sleep disorders – and get our lives back on track.

“Get our lives back on track…” How cheery. As if the old normal was all that great. Whose track? Going where? But slipping into “News You Can Use” mode, here are some tips on dealing with insomnia.

Conclusion

So that’s what I found out about Covid-19 and sleep. I’m sure there’s much more to learn. But it does occur to me that a sleep-deprived population with bad dreams that they’re remembering for the first time might be unusually cranky in the aggregate, even more than their material circumstances might dictate, and that this might be one factor behind the decrease in (dread word) civility that many have commented upon. Getting no sleep is bad.

NOTES

[1] No, I can’t find where we linked to this, which we did, because wherever you turn search doesn’t work anymore.

I would love to read other people’s anecdotes. Mine: my dreams haven’t changed since the pandemic, at least the ones I can recall. I still dream about traveling, for instance.

I have friends that grow several different kinds of pot and they have one that is especially good for getting to sleep and restful wakening. Not sure of the variety.

Indica.

Cannabis does suppress your dreams. I’m not sure of the mechanism, but a daily smoker who takes a break for a week or two (recommended!) usually experiences vivid dreams. Perhaps this is related to the notorious memory effects of pot.

Maybe that’s a good reason for cycling onto and off of cannabis . . . . to upvividise your dreams in the off cycle.

This is interesting. For most of my life I could NEVER remember a dream .. Only the feeling it induced upon waking. More recently I remember exact details of dreams. They’re generally not nice. But not necessarily “wrong”.

I’m one of those people who hasn’t always realised what I “should” be doing. I’ve seen doctors who are not “cuckoo weirdo types” who can see that my dreams are trying to make me think. What is right for me? Well I started a new job today. I’m not stupid. I know the covid risks. However my bonus to mental health was amazing. I’m back in the game. Sure, I might get covid (again?) and die. But I did something in my “first life” with a big textbook etc. If I die at 50 I’m not a failure. I achieved something.

In meantime I’ve got recruited to help docs get letters out to patients asap. I hope this helps. The recruitment story is funny and perhaps for another day but I’m just feeling great that I’m speeding along letters from docs.

Your new gig sounds great–it’s hard for people to wait for results. Encourages the rest of us to find something simple to help.

Great post. Thank you.

I have experienced broken sleep for a number of years, and have found that the best remedy for me is to unplug my wifi router before going to sleep. The result is a more sound sleep and if I do awaken, I return to sleep easily. YMMV. An interesting and challenging book about sleep is “Waking Up to the Dark. Ancient Wisdom for a Sleepless Age.” By Clark Strand. He writes about some sleep studies that changed the way I view broken sleep. He also writes about the negative effects of artificial light on humans and the benefits of sleeping in a totally darkened room. But the most startling narrative is about his experiences talking walks in the middle of the night.

Interesting! I assume you don’t use a smart phone as an alarm? or do you use it as alarm and leave it on data only?

I dreamed I was escorting Jesus from Chicago to Kansas, where Jesus planned to prepare for a career in pop music.

But when we got to Kansas, we had to go through customs.

Kansas customs operated out of sheds in primary colors (red and blue), but with subtle Japanese-looking detailing.

The customs lady was concerned that Jesus didn’t have a middle name. We went round and round about this.

Finally, I called for a Japanese brush, ink, and a scroll.

When these arrived, I painted a mystic symbol for the customs lady: a tiny yin-yang symbol in a circle, but with a long “descender” such as you might see on a lower-case “g.”

This satisfied her, and Jesus strode alone into the wheat fields, without stopping to thank me or to say goodbye.

Quite impressive honestly.

> Kansas customs operated out of sheds in primary colors (red and blue),

That’s very odd. In one dream I remember, I was in my old High School. The building trim inside (door frames and such) was all blue. The banners were blue. But my real HS school colors were red.

Could it be that the red/blue dichotomy has invaded our dreams? Anyone else?

Lambert Strether: I wouldn’t evoke the invented red/blue political dichotomy, which is a mess, anyway. After all, red traditionally is/was the color of revolution–as well as being a sign of joy and prosperity–even opulence–in most cultures. Think of how crimson is valued in Western culture. And Red Square in Moscow is named red for reasons not Leninist.

Blue has all kinds of divine attachments: I read an essay that posited that the rise of blue is related to the rise of Christianity. Mary, Mother of God, almost always has a blue cloak, and if she is related (without a doubt) to the great celestial goddesses like Diana and Hera, well, blue is signaling something else.

The question is: What do certain colors mean to you (rather than, Is a pop-culture shorthand meme leaking into your consciousness)? As I mention below: Paging Dr. Jung…

My dreams never take place in actual settings. Even if it’s “my apartment” in the dream, it bears no resemblance to any place I’ve lived or other apartment I can recall.

In fact, one of the distinguishing features of my dreams is the varied and excellent architecture. Plus often very elaborate plots.

Once in a while, I lucid dream (“This can’t be real” which I then test by flying, and then argue with myself as to why I can’t fly when awake) and quasi-lucid dreams (I rewind the dream and direct it down another plot path, but I am not as aware of it being a dream as when I fly).

However, one recurrent dream type is being at risk of getting to an airport late and having issues with packing.

Interesting! Thanks Lambert

I have longstanding issues maintaining circadian riddim and take Melatonin 2mg SR when I want to induce sleep. And it works very well. It’s not available OTC in Australia, except for people over 55 as of June this year

Last week I noticed with some wry amusement that in some of my dreams I would start to panic when I realised that I was in a crowded indoor space and not wearing a mask. Yeesh. It was not a dissimilar sensation to the dreams where you find yourself naked in public.

The night before last I dreamt I was living in an apartment in, I think, NYC which inexplicably had a nest of conspicuously and excessively large redback spiders. No idea what that portends.

I got on the Melatonin train to combat some sleep difficulties with ADD meds.

All I got to report back is my first nightmare where I stumble upon an abandoned smart phone in the dark forest and know immediately it belonged to my friend and he was kidnapped by gnomes.

Woke up as I hear something shuffling from the bushes towards me.

I’ve also had many recurring dreams since the pandemic of being in an indoor space and forgot to put my mask on. I panic and run out of the space while holding my breath – I feel very panicky. My dreams have always been very vivid and I nearly always could recall them – sometimes many days later.

About sleep disturbances – I’ve always noticed that if I’m coming down with something (a cold, flu) I don’t sleep well. I’m usually a very deep sleeper – can’t stand any kind of light in the bedroom. I’ve also been taking melatonin for years – so glad to hear about that in relation to Covid. I really do love sleeping.

Thanks, Lambert for an interesting post.

I have a doctor who recommended an anti-inflammatory regimen of omega 3 oils, vitamin D3 (with oil because it’s fat soluble), B-complex vitamins, a probiotic and melatonin. It’s been effective where my markers of inflammation are concerned.

I have a recurring dream that stretches back 30 some yrs. Always the same. Always. Vivid and more real than reality. Standing in what must be a kitchen, looking at the same cabinets and a corner of the room that I know must have a door but I cannot see it. It’s brightly lit, white vintage cabinets you would expect to see new in the 50’s, a bright yellow countertop. There’s an open window to my right just in my periphery, daylight outside, bright and clear. It’s empty-house in-the- country silent except for a slight breeze. The scene is always the same and you start with a calm and peaceful feeling, appreciating the perfect temp and fresh breeze, the somehow comforting cabinets, marveling at the serenity, the window, the breeze, wondering what road in the real world leads here…then it takes a turn, the spell is broke, you think of the corner, in shadow, the rear wall out of sight but you know, you feel, the door and that’s when an overwhelming sense of loss and dread washes over you and pushes you into conscience with the malaise firmly rooted in your waken state.

After all these years it’s become an old friend. I briefly know the play in full at the onset, then I’m engrossed in the strange repeating loop as if new and novel. One day the door wont matter, maybe the loop plays a final time, perhaps I will look through the window and into the yard.

After 500 million years of multicelled life-form selection, if sleep were actively damaging to organisms’ survival relative to non-sleep, organisms which did not sleep would have eventually outsurvived those that did sleep, and outreproduce them. That after all this time, all higher vertebrates at least still sleep, which I think goes to show that having-to-sleep does not hurt us any.

Now, what could sleep specifically be needed for? Here is an article about one particular thing which happens during sleep which is hypothesised to be necessary for the long term survival of the mice in whom this was discovered. And it is suspected to be true for people too, though I don’t know if any studies have been done on human volunteers.

https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/brain-may-flush-out-toxins-during-sleep

Andrew Huberman is good on this – it’s the glymphatic system washing out cellular bits ‘n pieces. He recommends yoga nidra (head below heart) during the day, instead of naps, to augment the effect. He’s also comprehensive on light stimulus and circadian rhythm. His youtube channel has a 3 hour discussion on sleep with Matthew Walker.

My own view on recollection of dreams is that it happens when the sleep cycle is broken – the brain’s workings-out carry over to the other side of the paper, into short-term memory. The content is insignificant, but the accompanying emotion is worth thinking about: a product of the disorderliness of the interrupted brain-washing, or the traumatized unconscious breaching the surface?

If the same thing happens in sleeping human brains as in sleeping mouse brains . . . that the sleeptime glial cells contract to create space for cerebrospinal fluid to move all around the brain cells . . . and then somewhere around wakeup the glial cells re-expand to force the brain cell trash filled fluid back into the general body circulation and disposal system , then i wonder whether the last few decades of mass sleep deprivation may be part of what is causing so much alzheimers disease in some of the underslept, hence undercleaned, brains.

I do remember when we moved away from the big Miami Airport. I couldn’t sleep well for weeks. The absence of noise kept waking me up. I eventually adapted to the quiet. Now I prefer it quiet. Yet, a friend in High School always had to have the radio playing softly next to him for him to sleep well. Take away the radio and he had terrible insomnia. Phyllis needs a night light to sleep soundly. I prefer dead dark, so I usually sleep in the other bedroom. Now that we have disconnected from the Work World, our sleep patterns are all over the place.

Stay safely sleepy!

During the lockdown I participated in an online survey about sleep and changes in state of mind and humour. Very much like Lambert I recalled more dreams. Sometimes I woke in the middle of the night one two or several times. I woke up later than usual.

Among the factors influencing sleep, apart from staying at home for too long hours i think it is important to question about exposure to computer,TV and smartphone screens which IMO should be avoided for a few hours before going to bed because they send a confused signal to our brains.

Paging Dr. Jung. Paging C.G. Jung. I am surprised that there is no mention in Lambert Strether’s main post or in the comments of C.G. Jung, who would find elaborate urgent dreams normal. Further, in a long-term crisis like the Covid pandemic, one would expect our minds to visit all kinds of archetypes and one would expect our unconscious to signal something going on in the big wide world of the collective unconscious.

For the most part, my dreams have been positive and have focused on continuing on: Not exactly survival, but a continuously functioning organism. Yet I have had memorable “Jungian” movies running in my head for years.

There is an aspect to such urgent dreaming that is divine: Not in a transcendent way, more in a chthonic way, the gods of the Earth, the prophetic gods, the ecstatic gods. Not revelation, either. More like epiphanies, the gods showing themselves through the great veil. (And Halloween and All Saints’ Day, now upon us, are times when the veil is more diaphanous than ever.)

I find that I need supplemental Magnesium, melatonin, and an adequate amount of outdoor exercise (about an hour of walking) during the day to get a decent nights sleep.

PS: for Dr Jung

The recurring theme in my dreams for last few years has been being lost, without resources, and struggling to find my way home.

This morning-just before reading Lamberts post-was a dream in which I was asleep and desperately needed to awaken. My family was ignoring me and would not help me awaken.

For most of my life my dreams have been symbolic and pragmatic messages about life issues.

Also, light, inadequate and Fractured sleep is apparently common in old age.

Things are bad enough with the Corona flu. I hope no one dreams like the dreamer in Le Guin’s “Lathe of Heaven”. It would be too hard to keep up with the changes.

The night I got the second Pfizer vaccine almost two months ago was the beginning of what is by far the longest and worst insomnia I’ve had in my life. I have no trouble getting to sleep, but typically wake up three hours later feeling quite awake. I hadn’t had this sort of insomnia ever and wasn’t having much insomnia before the shot, so it seems the vaccine was the cause, or at least an important one. The info on melatonin is useful. Thanks, Lambert! I wonder if other people have experienced anything similar after vaccination. I’ve always tended to remember dreams, but the insomnia has strengthened that tendency. I’m having to manage my sleep carefully every day. Like most recipients of the vaccine I haven’t been asked about side effects. … Posted at 3:15 am

Thanks for this, Lambert. I don’t dream much anymore, unless it’s what I call a “Fellini dream”, an absolute, crazy, brilliant circus. I have had predictive and recurrent dreams. One was of dying by bleeding from the head/mouth trying to call for help (hellooo Jungians out there..). Went on for years. It finally happened, but I survived. Never had that dream again. Anyone else had these?? Just curious. I remember reading about “first and second sleeps” in ancient times. (Being a night owl, I sort of get it!)

No difference with the vaccine, though. Just regular crappy sleep of a resistant night owl! (That’s why my comments are, uh, late!)

1) Reds and blues: years ago, I read a whole stack of books by the left-leaning “social” historians of the French Revolution. Mathiez. Soboul. And others.

In one of these books, I read that before the Revolution, the red flag stood for martial law, and was hoisted by the army as a warning to us ordinary people to get out of the streets.

But one day, in the early days of the Revolution, Lafayette and the new National Guard, THEMSELVES, hoisted the red flag–an assertion of martial law on behalf of the people, against the aristocrats.

If this ISN’T true, it SHOULD be. And I did read it.

The Paris unemployed, I also remember, were put to work–tearing down the Bastille.

2) I’ve been reading NC for years, and feel true affection for and gratitude to the commentariat, as well as the heroic figures who created this wonderful institution.

I can’t imagine what my life would have been like in recent years without NC.

What a wonderful “dreams” discussion.

One important way in which Covid-19 could be negatively impacting our sleep patterns is by confining ourselves indoors most of the time by way of lockdowns or working from homes and depriving us from bright daylight which has vital role in conditioning our circadian rhythms. Below is a link on the subject.

https://www.sleepfoundation.org/bedroom-environment/light-and-sleep