Yves here. Leroy R recommended the last Gail Tverberg piece, where she broadens out from her usual focus on energy to the issues of complexity and collapse. I decided to repost it because it’s meaty and thus likely to provoke a good discussion.

That said, while I agree completely with her overview statement, that the trend towards complexity has gone too far, I have to beg to differ with her in making energy a central driver. What has made the increase in “complexity” destabilizing is that it involves tight coupling, so that when a disruption occurs, it propagates across the system and the process cannot be halted. You can have a complex system without tight coupling if it has features like buffers or self-contained, segregated sub-processes, or redundancies.

While Jacques Tainter’s book on collapse is seminal, its focus on rising energy as the sole explanation never seemed satisfactory, particularly since it didn’t serve to explain why some societies collapsed while others were on that trajectory yet pulled themselves out. Tainter also rejected culture as having any explanatory power, when culture probably had a fair bit to do with how these societies were able to become complex in the first place.

The big impetus for the Reagan era was not energy prices but in a classic “never let a crisis go to waste” sense, it sure helped. Many of our US readers likely know that a hard core right wing movement, with John Birchers, the Kochs, and the Cohrs family as charter members, was crystalizing in the 1960s, before the oil crisis, to turn back New Deal reforms and re-establish the primacy of business in American society. This initiative was codified in the Powell Memo of August 1971, again more than two years before the oil shock of 1973. These conservatives were greatly helped by the fact that the new Keynesian whiz kids posited an inflation-growth tradeoff (the Phillips curve) which was then shown to be wrong when stagflation settled in. By contrast, Milton Friedman had warned against LBJ’s deficit spending as too simulative (as had Democratic economist Walter Heller, but everyone seemed to forget that a liberal had been on the same page) and became the new economic star. Friedman understood the important of propaganda, um, polemics, and was extremely skilled at making middle-class hostile neoliberal policies sound sensible, even enlightened, and broadly beneficial when they were anything but.

And neoliberalism’s primary, if covert aim, was to reduce labor rights and incomes to favor managers, executives, investors, and their close advisors. The relentless pursuit of efficiency, even at the expense of increasing risk at the company-level and system-wide, wasn’t just thoughtless short-termism and profiteering. Had anyone thought about it, this was yet another elite “Heads I win, tails you lose” bet. Those at the top of the food chain, generally speaking, are in a vastly better position to ride out disruptions than the peons.

By Gail Tverberg, an actuary interested in finite world issues – oil depletion, natural gas depletion, water shortages, and climate change. Originally published at Our Finite World

The world economy requires stability. People living in the world economy need stability, as well. They need food every day and a place to live. Children need a home situation that they can count on.

Back in the 1950 to 1979 era, when energy supplies of many kinds were growing rapidly, it was possible to build stability into the economic system: Jobs with a company were often long-time careers; pensions after retirement were offered; electricity was sold through regulated “utilities” that charged prices that wrapped in long-term maintenance of the electric grid and the cost of fuel, among other things.

But as high energy prices hit in the 1970s, the system became more and more strained. The mood changed. Margaret Thatcher became the Prime Minister of the UK in 1979, and Ronald Reagan became President of the United States in 1981. Under their leadership, debt was increasingly used to cover longer-term costs, and competition was encouraged. A person might say that a move toward greater complexity, but less stability, of the economic system had begun.

Now, through several iterations, the economy has become increasingly complex, with less and less redundancy to provide stability. The energy price spike that is being experienced today is a warning that something is very, very wrong. As I see the situation, the trend toward complexity has gone too far; the economic system is starting to break down. Sharp changes appear to be ahead. The world economy is shifting into contraction mode, with more and more parts of the system failing.

In this post, I will discuss some of the issues involved. It turns out that energy modelers haven’t understood how detrimental intermittency really is. They modeled intermittent electricity from renewables (wind, water and solar) as far more helpful than it really is.This has been confusing to everyone. The sharp changes that the title of this post refers to represent an early stage of economic collapse.

[1] If energy supplies are inexpensive and widely available, it is easy to build an economy.

I have written in the past about the need for energy supplies to keep the economy functioning properly being analogous to the need for food, to keep humans functioning properly.

The economy doesn’t operate on a single type of energy, any more than a human lives on a single type of food. The economy uses a portfolio of energy types. These include human labor, energy directly from sunlight, and energy from burning various types of fuels, including biomass and fossil fuels.

As long as energy sources are inexpensive and readily available, an economy can grow and provide goods and services for an increasing number of citizens. We can think of this as being analogous to, “As long as buying and preparing food takes little of our wages (or time, if we are growing it ourselves), then there are plenty of wages (or time) left over for other activities.”

But once energy prices start spiking, it looks like there is not enough to go around. In the absence of ways to hide the problem, citizens need to cut back on non-essentials, pushing the economy into recession. Or businesses stop making essential products that require natural gas or coal, such as fertilizer or fuel additives to hold emissions down. The lack of such products can, by itself, be very disruptive to an economy.

[2] Once energy supplies become constrained, energy prices tend to spike. In the early stages of these price spikes, adding complexity allows the economy to better tolerate higher energy costs.

There are many ways to work around the problem of rising energy prices, at least temporarily. For example:

- Build vehicles, such as cars, that are smaller and more fuel efficient.

- Extend fossil fuel supplies by building nuclear power plants, hydroelectric generating plants, wind turbines, solar panels, and geothermal electricity generation.

- Make factories more efficient.

- Add insulation to buildings; eliminate any cracks that might allow outside air into buildings.

- Instead of pre-funding capital costs, use debt to transfer these costs to later purchasers of energy products.

- Encourage competition in providing different parts of electricity production and distribution.

- Develop time-of-day pricing for electricity, so as to keep prices down to the marginal cost of production, even though this does not, in total, repay all costs of production and distribution.

- Cut back on routine maintenance of electricity transmission systems.

- Purchase coal and natural gas imports using spot pricing, rather than long term contracts, as long as these seem to be lower-priced than long-term commitments.

- Throughout the economy, take advantage of economies of scale and mechanization. Build huge companies. Replace human labor wherever possible.

- Stimulate the economy by increasing debt availability and lowering interest rates. This is helpful because a more rapidly growing economy can withstand higher energy prices.

- Use global supply chains to source as large a share of manufacturing inputs as possible from countries with low wages and low energy costs.

- Build very “lean” just-in-time supply chains.

- Create complex financial systems, with debt resold and repackaged in different ways, futures contracts, and exchange traded funds.

Together, these approaches comprise “complexity.” They tend to make the economic system less resilient. At least temporarily, they pass fewer of the higher costs of energy products through to current citizens. As a result, the economy can temporarily withstand a higher price of energy. But the system tends to become brittle and prone to failure.

[3] There are limits to added complexity. In fact, complexity limits are what are likely to make the economic system fail.

Joseph Tainter, in The Collapse of Complex Societies, makes the point that there are diminishing returns to added complexity. For example, the changes that result in the biggest gains in fuel savings for vehicles are the ones added first.

Another drawback of added complexity is the extreme wage disparity that tends to result. Instead of everyone earning close to the same amount, those at the top of the hierarchy get a disproportionate share of the wages. This is what leads to many of the problems we are seeing today. Would-be workers don’t want to apply for jobs, even when they seem to be available. Citizens become unhappy and rebellious. Lower-paid workers may not eat well, so that pandemics spread more easily.

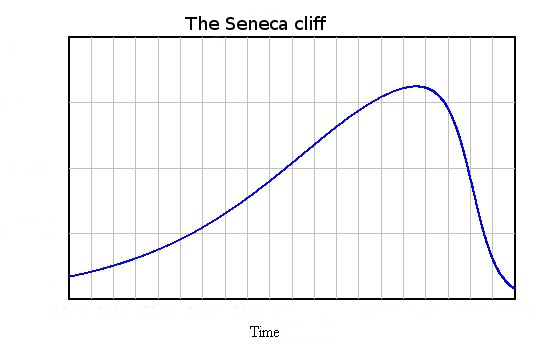

The underlying problem is that population tends to rise, but it becomes harder and harder to produce food and other necessities with the arable land and energy resources available. Ugo Bardi uses Figure 1 to show the shape of the expected decline in goods and services produced in such a situation:

According to Bardi, Seneca in the title refers to a statement written by Lucius Annaeus Seneca in 91 CE, “It would be of some consolation for the feebleness of ourselves and our works if all things should perish as slowly as they come into being. As it is, increases are of sluggish growth, but the way to ruin is rapid.” In fact, this shape seems to approximate the type of cycle Turchin and Nefedov observed when analyzing several agricultural civilizations that collapsed in their book Secular Cycles.

[4] An increasing amount of complexity has been added since 1981 to help compensate for rising oil and other energy prices.

The prices of commodities, including oil, tend to be extremely variable because storage is very limited, relative to the large quantities used every day. There needs to be a very close match between supply and demand, or prices will rise very high or fall very low.

Oil is exceptionally important because it is the single largest source of energy for the world economy. It is heavily used in food production and in the extraction of minerals of all types. If the price of oil increases, the price of food tends to rise, as does the price of metals of many types. Oil is also important as a transportation fuel.

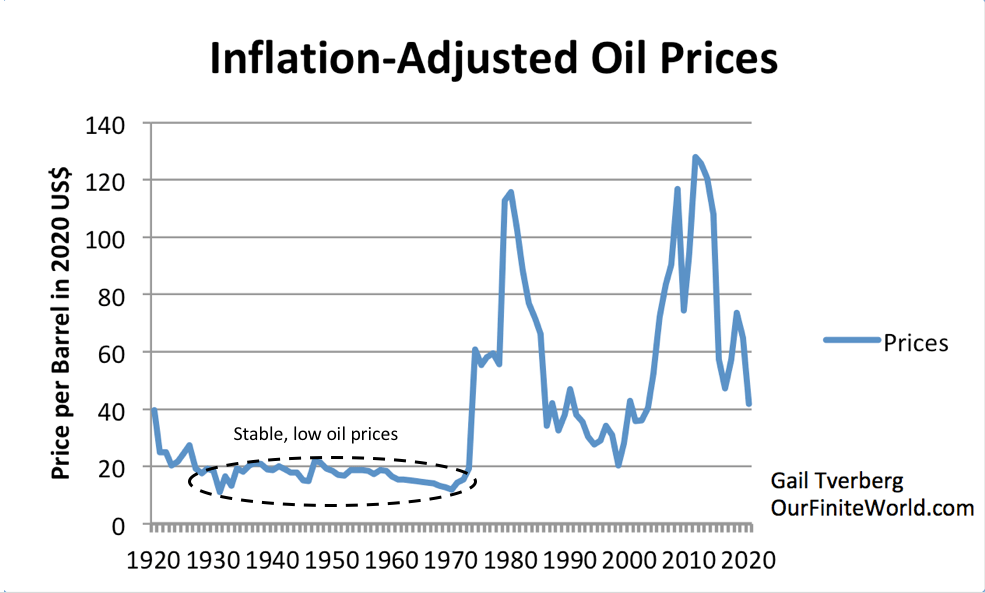

In the early days, before depletion led to higher extraction costs, oil prices remained stable and low (Figure 2), as a result of utility-type pricing by the Texas Railroad Commission. Oil prices started to spike, once depletion became more of a problem.

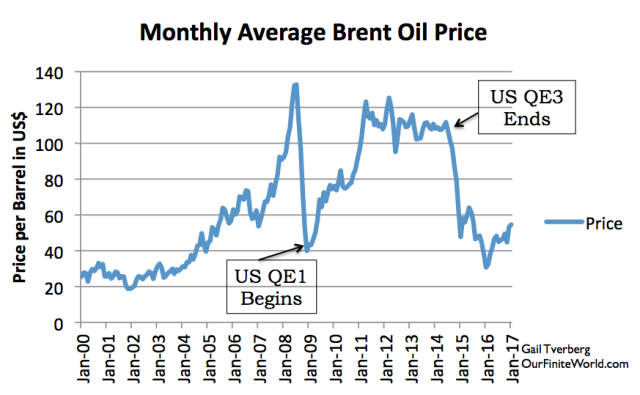

Economists tell us that oil and other commodity prices depend on “supply and demand.” When we look at turning points for oil prices, it becomes clear that financial manipulations play a significant role in determining oil demand. Such manipulations lead to prices that have practically nothing to do with the underlying cost of producing commodities. The huge changes in prices seem to reflect actions by central bankers to encourage or discourage lending (QE on Figure 3).

Quantitative easing (QE) makes it cheaper to borrow money. Adding QE tends to raise oil prices; deleting QE seems to reduce oil prices. These prices have little direct connection with the cost of extracting oil from the ground. Instead, prices are closely related to the amount of complexity being added to the system and whether it is having its intended impact on energy prices.

At the time of the 1973-1974 oil crisis, many people thought that the world was truly running out of oil. The petroleum industry did, indeed, succeed in extracting more. The 2005 to 2008 period was another period of concern that the world might be running out of oil. Then, in 2014, when oil prices suddenly fell, the dominant story suddenly became, “There is plenty of oil. The world’s biggest problem is climate change.”

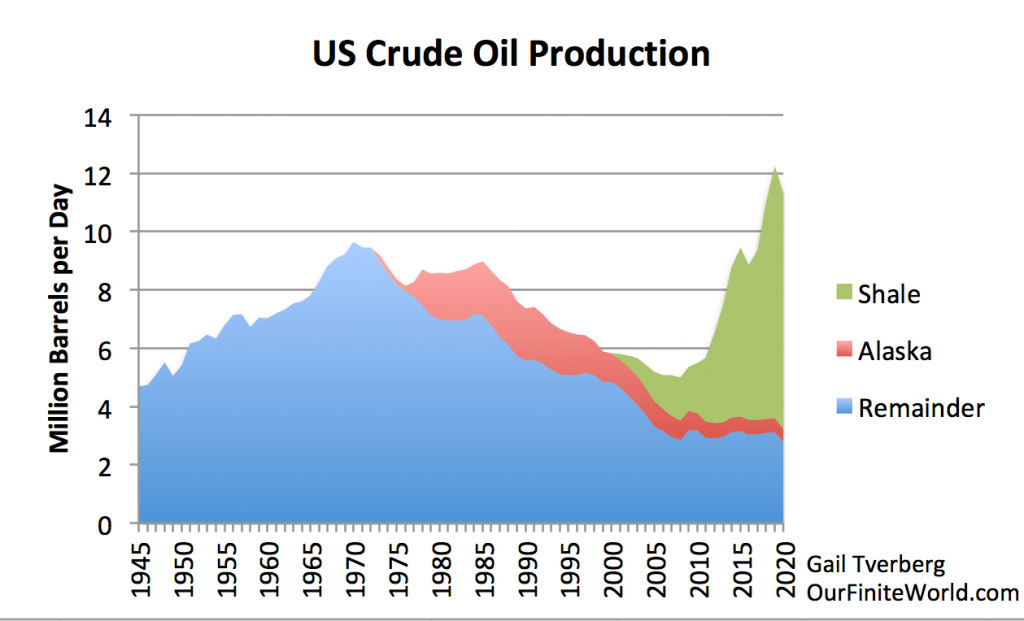

In fact, there was no real reason to believe that the shortage situation had changed. US oil from shale had a brief run-up in production in the 2007 to 2019 period, but this production was unprofitable for producers, especially after oil prices dropped in 2014 (Figures 2 and 3). Producers of oil from shale are. no longer investing very much in new production. With the sweet spots of fields depleted and this low level of investment, it will not be surprising if oil production from shale continues to fall.

Figure 4. US crude and condensate oil production for the 48 states, Alaska, and for shale basins, based on data of the US Energy Information Administration.

The real story is that the supply of oil, coal and natural gas is limited by the extent to which additional complexity can be added to the economy, to keep selling prices so that they are both:

- High enough for producers of these products, so that they can both pay adequate taxes and make adequate reinvestment.

- Low enough for consumers, especially for the many consumers around the world with very low wages.

Many people have missed the point that, at least since 2014, financial manipulations have not kept prices for fossil fuels high enough for producers. Low prices are driving them out of business. This is the case for oil, coal and natural gas. In fact, low prices caused by giving wind and solar priority on the electric grid are driving producers of nuclear electricity

out of business, as well.

Oil producers require a price of $120 a barrel or more to cover all of their costs. Without a much higher price than available today (even with oil prices over $80 per barrel), shale oil production can be expected to fall. In fact, OPEC and its affiliates won’t ramp up production by very large amounts either because they, too, need much higher prices to cover all their costs.

[5] Economists and analysts of many types put together models that give misleading results because they missed several important points.

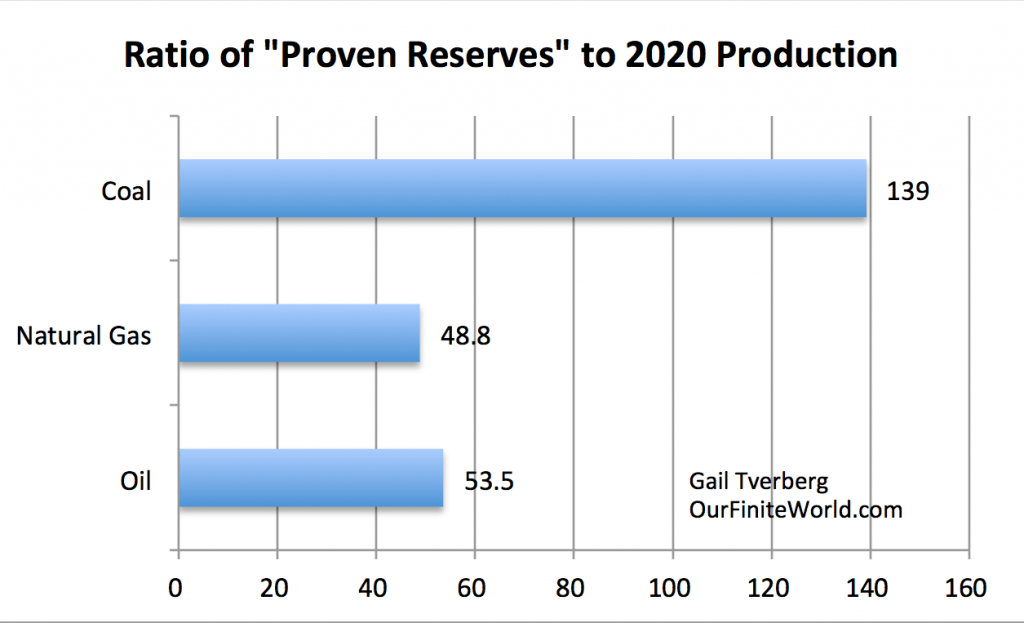

After oil prices fell in late 2014, it became fashionable to believe that vast amounts of fossil fuels are available for extraction, and that our biggest problem in the future would be climate change. Besides low prices, one reason for this concern was the high level of fossil fuel proven reserves reported by many countries around the world.

Even fossil fuel companies started to invest in renewables because of the poor returns experienced from fossil fuel investments. It looked to them as if investment in renewables would be more profitable than continued investment in fossil fuel production. Of course, the profits of renewables were largely the result of government subsidies, particularly the subsidy of “going first.” Giving wind and solar first access when they happen to be available tends to lead to very low, and even negative, wholesale prices for other electricity producers. This drives these other producers of electricity out of business, even though they are really needed to correct for the intermittency of renewables.

There were many things that hardly anyone understood:

- Fossil fuel producers need to be guaranteed long-term high prices, if there is to be any chance of ramping up production.

- Intermittent renewables (including wind, solar, and hydroelectric) have little value in a modern economy unless they are backed up with a great deal of fossil fuels and nuclear electricity.

- Our real problem with fossil fuels is a shortage problem. Price signals are very misleading.

- <>The models of economists are mostly wrong. The use of carbon pricing and intermittent renewables will simply disadvantage the countries adopting them.

The reason why geologists and fossil fuel producers give misleading information about the amount of oil, coal and natural gas available to be extracted is because it is not something they can be expected to know. In a sense, the question is, “How much complexity can the economy withstand before it becomes too brittle to handle a temporary shock, such as a pandemic shutdown?” It isn’t the amount of fossil fuels in the ground that matters; it is the follow-on effects of the high level of complexity on the rest of the economy that matters.

[6] At this point, ramping up fossil fuel production would be very difficult because of the long-term low prices for fossil fuels. Unfortunately, the economy cannot get along with only today’s small quantity of renewables.

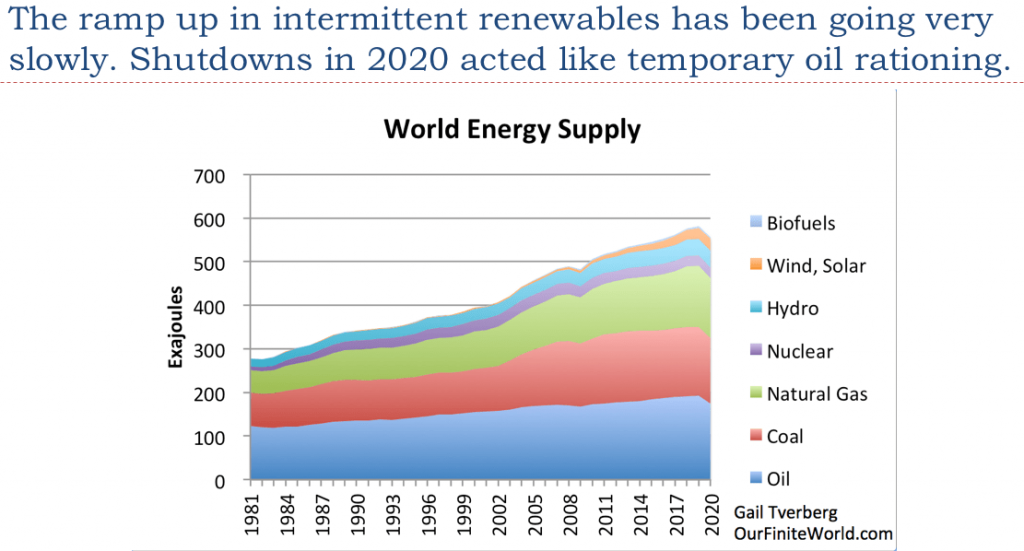

Most people don’t realize just how slowly renewables have been ramping up as a share of world energy supplies. For 2020, wind and solar together amounted to only 5% of world energy supplies and hydroelectric amounted to 7% of world energy supplies. The world economy cannot function on 12% (or perhaps 20%, if more items are included) of its current energy supply any more than a person’s body can function on 12% or 20% of its current calorie intake.

Also, the world’s reaction to the pandemic acted, in many ways, like oil rationing. Figure 6 shows that consumption was reduced for oil, coal and natural gas. An even bigger impact was on the prices of these fuels. Prices fell, even though the cost of production was not falling. (See, for example, Figure 2 for the fall in oil prices.)

These lower prices left fossil fuel providers even worse off financially than they were previously. Some providers went out of business. They certainly do not have reserve funds set aside to develop the new fields that they would need to develop, if they were to ramp up production for oil, coal and natural gas now. Because of this, it is virtually impossible to ramp up fossil fuel production now. A lead time of at least several years is needed, besides a clear way of funding the higher production.

[7] Every plant and animal and, in fact, every growing thing, needs to win the battle against intermittency.

As mentioned in the introduction, humans need to eat on a regular basis. Hunter-gatherers solved the problem of intermittency of harvests by moving from area to area, so that their own location would match the location of food availability. Early agriculture and cities became possible when the growing of grain was perfected. Grain was both storable and portable, so it could be used year around. It could also be brought to cities, allowing people to live in a different location from where the crops were stored.

>We can think of any number of adaptations in the plant and animal kingdom to intermittency. Some birds migrate. Bears hibernate. Deciduous trees lose their leaves each fall and grow them back again each spring.

Our supply of any of our energy products is in some sense intermittent. Oil wells deplete, so new ones need to be drilled. Biomass burned for fuel grows for a while, before it is cut down (or falls down) and is burned for fuel. Solar energy is available only until a cloud comes in front of the sun. In winter, solar energy is mostly absent.

[8] Any modeling of the cost of energy needs to take into account the full system needed to “bridge the intermittency gap.”

As far as I can see, the only pricing system that generates enough funds is one that takes into account the full system needs, including the need to overcome intermittency and the need for transportation of the energy to the user. In fact, I would argue that even more than this needs to be included. Good roads are generally required if the system is to be kept in good repair. Good schools are needed for would-be workers in the energy system. Any costs associated with pollution should be wrapped into the required price. Thus, the true cost of energy generation really should include a fairly substantial load for taxes for all of the governmental services that the system requires. And, of course, all parts of the system should pay their workers a living wage.

This high level of pricing can only be provided by utility type pricing of fossil fuels and electricity. The use of long-term contracts to purchase fossil fuels, uranium or electricity can also build in most of these costs. The alternative approach, buying fuels using spot contracts or pricing based on time of day electricity supply, looks appealing when costs are low. But such systems don’t build in sufficient funding for replacement of depleted fields or the full cost of a 24/7/365 electrical system.

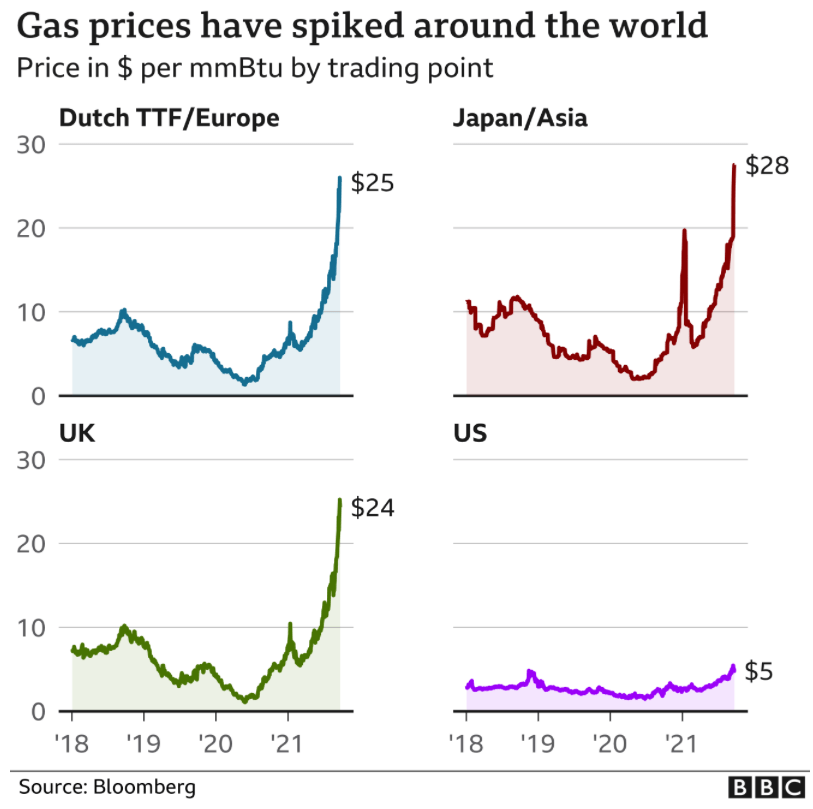

Modelers didn’t understand that the “low prices now, higher prices later” approaches that were being advocated don’t really work for the long term. As limits are approached, prices tend to spike badly. Modelers had assumed that the economic system could handle such spikes in prices, and that the spikes in prices would quickly lead to new supply or adaptation. In fact, huge spikes in prices are very disruptive to the system. New supply is what is really needed, but providers tend to be too damaged by previous long periods of artificially low prices to provide this supply. The approach looks great in academic papers, but it leads to rolling blackouts and unfilled natural gas reservoirs for winter.

[9] Major changes for the worse seem to be ahead for the world economy.

At this point, it seems as if complexity has gone too far. The pandemic moved the world economy in the direction of contraction but prices of fossil fuels tend to spike as the economy opens up.

The recent spikes in prices are highly unlikely to produce the natural gas, coal and oil that is required. They are more likely to cause recession. Fossil fuel suppliers need high prices guaranteed for the long term. Even if such guarantees could be provided, it would still take several years to ramp up production to the level needed.

The general trend of the economy is likely to be in the direction of the Seneca Cliff (Figure 1). Everything won’t collapse all at once, but big “chunks” may start breaking away.

The debt system is a very vulnerable part. Debt is, in effect, a promise of goods or services made with energy in the future. If the energy isn’t there, the promised goods and services won’t be available. Governments may try to hide this problem with new debt, but governments can’t solve the underlying problem of missing goods and services.

Pension systems of all kinds are also vulnerable. If fewer goods and services are being made in total, they will need to be divided up differently. Pensioners are likely to get a reduced share, or nothing at all.

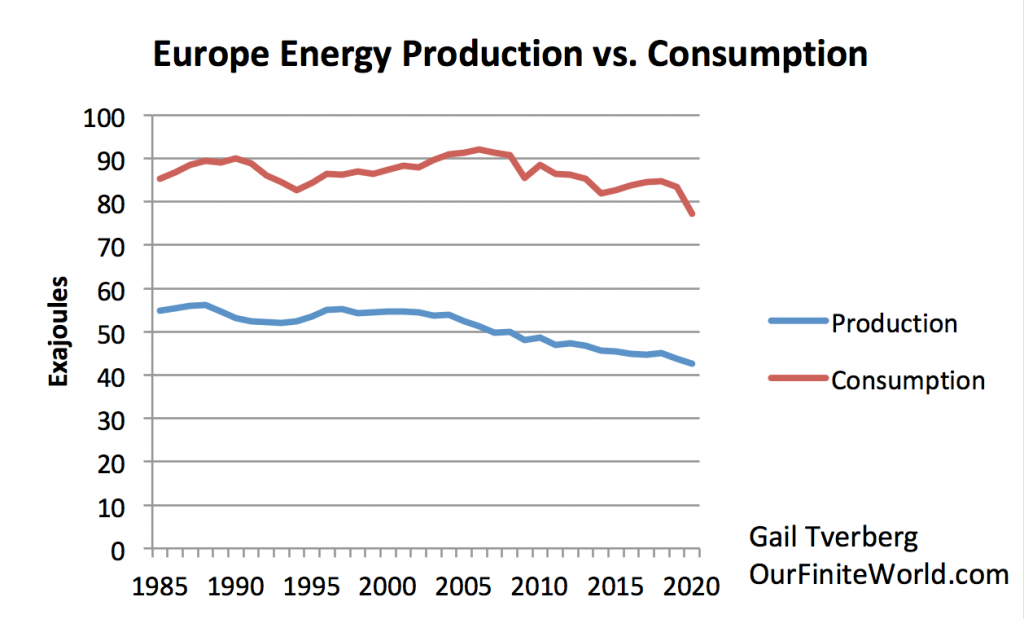

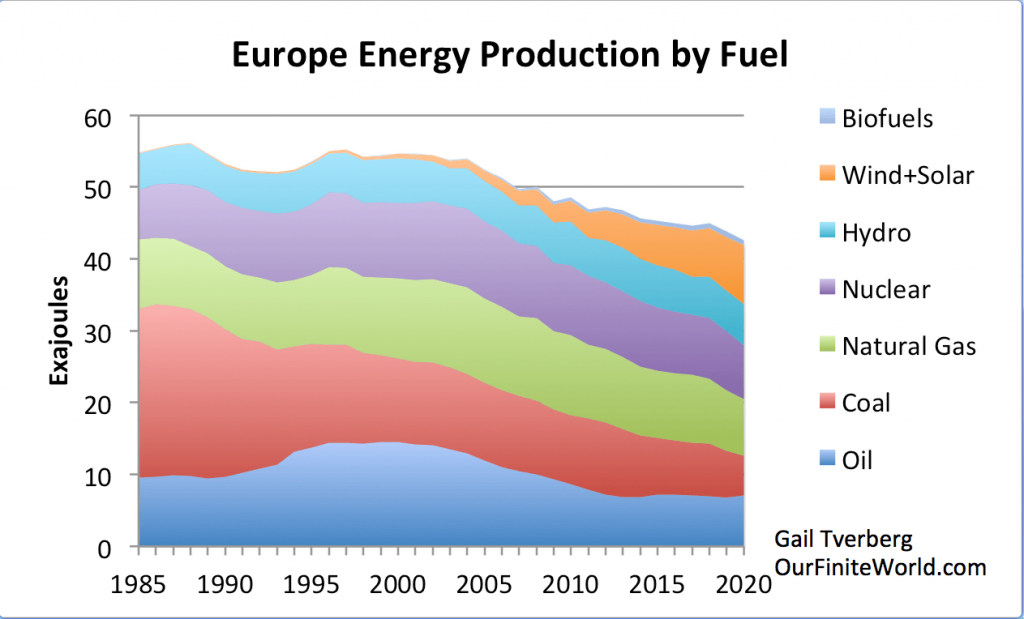

Importers of fossil fuels seem likely to be especially affected by price spikes because exporters have the ability to cut back in the quantity available for export, if total supply is inadequate. Europe is one part of the world that is especially dependent on oil, natural gas and coal imports.

The gap between consumption and production is filled by imports of oil, coal, natural gas and biofuels. Within Europe, countries also import electricity

from each other.

The combined production of hydroelectric, wind and solar and biofuels (in Figure 9) amounts to only 19% of Europe’s total energy consumption (shown in Figure 8). There is no possible way that Europe can get along only with renewable energy, at any foreseeable time in the future.

European economists should have told European citizens, “There is no way you can get along using renewables alone for many, many years. Treat the countries that are exporting fossil fuels to you very well. Sign long term contracts with them. If they want to use a new pipeline, raise no objection. Your bargaining power is very low.” Instead, European economists talked about saving the planet from carbon dioxide. It is an interesting idea, but the sad truth is that if Europe takes itself out of the contest for energy imports, it mostly leaves more fossil fuels for exporters to sell to others.

China stands out as well, as the world’s largest consumer of energy, and as the world’s largest importer of oil, coal and natural gas. It is already encountering electricity shortages that are leading to rolling blackouts. In fact, rolling blackouts in China started almost a year ago in late 2020. China is, of course, a major exporter of goods to the rest of the world. If China has major energy problems, the rest of the world will no longer be able to count on China’s exports. Lack of China’s exports, by itself, could be a huge problem for the rest of the world.

I could continue speculating on the changes ahead. The basic problem, as I see it, is that we have reached limits on oil, coal and natural gas extraction, pretty much simultaneously. The limits are really complexity limits. The renewables that we have today aren’t able to save us, regardless of what the models of Mark Jacobson and others might say.

In the next few years, I am afraid that we will find out how collapse actually proceeds in a very interconnected world economy.

To me for decades it has seemed like the perpetrators are like drug dealers–get people hooked on crack (oil, debt, junk food) then keep cranking up the prices, on gas, interest rates on debt, health care. Bad parasite. But they think the support system they built socking all that profit into their portfolios in the ether will save them. They have forgotten they, and their children, are still in human bodies, connected to Earth. And that Pelosi thing about ‘Catholic values’ she shares with Manchin. As a child I wondered at those bloody depictions of Christ on the cross with the railroad spikes. Yeah, he healed the sick for free, advocated love and compassion, and fed the multitudes with what was at hand, and look what happened to him. It seems like a warning now–what a rube!

Maybe we should listen to a different Seneca.. ‘The Code of Handsome Lake’. Combine Native American beliefs with the Quakers .

(Keep the Navy strong though, just in case..)

“generally speaking, are in a vastly better position to ride out disruptions than the peons.” Up to a certain level, anyways.

As an aside, I believe Phillips curve is a fascinating artifact of economy meets academia in the worst possible sense.

My recollection is that Phillips was happily building his pneumatic models of economy at LSE, when someone noticed he’s not a Professor, partially due to a lack of papers published in “serious” journals. So he was asked to write one, which he hated doing, so he just bumped together a paper on something quickly, which turned out to be this relationship. And then it took a life on its own. Again, if I remember correctly, he hated it for the rest of his life, although kept quiet of it, as it allowed him to do what he wanted, tinkering with his MONIAC (pun was intended).

I do agree that it is hard to overstate the physical importance of energy in an economy just like it is hard to overstate the importance of labour. Nothing can be done without some energy in some form, an economy cannot exist. Likewise if we had REALLY cheap energy almost anything physical can be accomplished and much more cheaply.

This piece touches on many pertinent points. Though I think it is too focussed on fossil fuels without considering the earlier point made about storage in enough detail. Though looking at her blog it would seem she doesn’t see that there are viable alternatives to fossil fuels.

Storage is critical for the very intermittent but cheap and clean solar and wind. It is also critical in price stability of fossil fuels as negative oil prices showed us. I would argue that we have been and still are asleep at the wheel when it comes to navigate ourselves away from fossil fuel dependence. It has become fashionable to promote non fossil fuel energy sources but we continue to ignore the elephants in the room of storage. (both electrical and chemical energy storage; chemical being hydrogen/methanol/ammonia etc)

No we haven’t. We are just experiencing a price spike due to many of the aforementioned reasons in the article. I do agree that it could be a painful adjustment though.

Too many times I read ‘intermittent renewables’ as a mantra here. As if energy storage is not ramping up nearly explosively including here batteries and hydrogen (from very low lows certainly but something not to be missed anyway).

Another thing I miss is the ‘energy cost of energy’ (energy losses in the grid), which is about 34% not something that can be missed, and greatly depends on very much centralized systems with fossil fuel and nuclear plants.

Yet I totally agree with the title: sharp changes ahead.

Yes, I really hate the use of ‘intermittent’ as a mantra. All fuel sources are intermittent and require storage, it just takes different forms for different fuels and mixes. There is no ‘perfect’ fuel for electricity generation or for industrial purposes. They key is always getting the mix right for the particular grid (and every grid is radically different, often for obscure historical or technical reasons. People who single out solar and wind because of ‘the intermittency problem’ either don’t understand how grid and energy systems work, or they are engaged in bad faith argumentation. All power systems require storage and redundancies if you don’t want brown/blackouts.

This is not, of course, to downplay the technical obstacles to creating a grid dependent on solar/wind for the majority of power, but the problems are technical ones that do not require any major scientific or engineering breakthroughs. Its a question of will and a question of structural/infrastructural planning.

Yes…and no. Oil and coal can be easily stored (relatively speaking). Solar and wind cannot be easily stored; not now and not for the foreseeable future. A few tens of thousands Tesla batteries will not substitute for massive oil storage tanks or trainloads of coal.

They can be easily stored, but way less easy to transport.

TBH, solar and wind can be now also stored, indirectly via hydrogen/methane production, but then you again get into the transport problem (it’s no fun transporting hydrogen..), although in theory methane could use existing CPG/LPG infrastructure.

Your second statement is demonstrably untrue. Large scale electricity storage has been constructed and used worldide for many decades – mostly pumped hydro. I regularly hike around the 292 MW capacity Turlough Hill Station which is nearly half a century old and is still operating perfectly. It is in fact part of a series of storage hydro systems – water being pumped either side of existing hydro stations. These are extremely common on small grids worldwide, from Ireland and the UK and Portugal to Japan and elsewhere. They have fallen out of favour to a certain degree because wider grid connections and cheaper gas peaking supply made them less attractive. But a variety of other technologies are in wide use worldwide depending on the particular local grid requirements. Flow battery installation is now very common on windfarms worldwide, although they are likely to be replaced by the newer thermal and liquid air systems that are now being scaled up.

Storage of renewable energy is a lot more difficult than storage of say, fossil fuels.

It will require overcapacity and storage.

I’m not at all convinced that lithium ion batteries are reliable for this. They lose their charge after too few charge and discharge cycles. On a small scale, they are fine, but for large scale, it is going to be a lot more difficult.

https://www.technologyreview.com/2018/07/27/141282/the-25-trillion-reason-we-cant-rely-on-batteries-to-clean-up-the-grid/

We should not deny global warming, but denying the potential solutions have challenges is a surefire way to problems.

To give an example, California had blackouts in part due to the swap to solar and was forced to turn to natural gas, at least temporarily.

https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/california-to-build-temporary-gas-plants-to-avoid-blackouts-1.1642188

The problem is that natural gas tends to emit methane, which is many times more powerful than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas.

Germmay had to turn to coal due to weak wind output.

https://www.dw.com/en/germany-coal-tops-wind-as-primary-electricity-source/a-59168105

There are no simple solutions. So the intermittent concern is well justified and will remain a serious barrier to renewable energy becoming a higher percentage of the total amount of electricity output.

Lithium ion batteries are not the solution, and apart from Elon Musk, nobody is claiming they are. They are currently popular simply because scaling makes them relatively cheap. But storage is not simply a case of ‘storing electricity until its needed’, there are a range of stages, from the transition from when one power source goes down and another kicks in (this is handled by capacitors or similar), short term storage (2-3 hours), where lithium ion batteries are currently the most cost-effecive, to longer term storage, where flow batteries, thermal, gravity and other sources kick in. In reality, all grids need, and will increasingly in the future need, a wide variety of storage types and scales. There is also a lot of current interest now in simply using surplus power for other uses, such as making hydrogen or ammonia for storage or industrial use. Most investment now is focusing on flow batteries and liquid air or thermal solutions.

But the most obvious solution, and the one that is being most actively pursued in China and Europe, is not storage, but simply bigger networks. Solar and wind are only intermittent on a regional scale. There is always sunshine and wind somewhere in the world. For the initial period of investment, longer DC lines makes the most sense. The problem with implementing these in the US is political and legislative, its not a technical or economic one.

Longer power lines are not the answer. In California PG&E has been unable to maintain and safely operate their extensive grid of power lines, costing many lives and many billions of dollars. In addition, power lines are unsightly and spoil landscapes.

This is a non-sequitur. Just because PG&E can not maintain their lines doesn’t mean they can not be managed properly. In my opinion, California’s power line problem is a product of neo-liberal style deregulation and privatization.

Citing California fires as a reason to dismiss high voltage, long distance transport of electric power is not a legitimate rebuttal to PK in this matter in at least two critical ways: 1) the utilities can do better maintenance, as they managed to do in the past, and 2) wildfires are rarely set off by high voltage, long distance transport lines.

PG&E is capable of maintaining their lines more effectively than they do. All their lines. However, it is the end-of-line part of their system that is the key issue, specifically the secondary and tertiary lines that deliver electricity to end users, not the ‘high tension’ lines you see as “spoiling the landscape”. (Also, a fair number of fires are sparked by ground infrastructure, not lines).

The end-of-line and most complex part of the distribution system has been responsible for most electric-system spawned wildfires in the far west. Unless we all transition back to gas lamps and gas-powered appliances, end-of-line electricity distribution will remain ‘a thing’ in the west and everywhere else, irrespective of the location and type of generation behind it. And it will likely remain the primary source of electricity-spawned wildfire.

Long distance HDVC lines have been working fine all around the world. The Chinese and Europeans are constructing lines at cross-continental scale using technology that is now very mature. There are no fundamental technological obstacles to new lines crossing the US, its entirely down to the incompetence and corruption of US power companies that existing lines have failed.

Is it just me, or is there really an increase in the “this is a pie in the sky thing, because it doesn’t work in the US” comments – some in the NC commentariat, but many more outside?

There is plenty of it around. I honestly don’t know if its ‘organic’, or its deliberate, given that often industry funded astroturfing starts in the US and then spreads, often by people completely unaware that they are regugitating ‘facts’ generated by PR companies. This is particularly common with anti-windfarm commentary.

The average age of those power lines in California is about 70 years old. About the time that Harry S. Truman was President. One that started a fire in California was erected during the Warren G. Harding administration while there are others older yet. That is why the Californian power supply is rubbish. Not so much because a lot of that gear is old but that PG&E has been taking the profits while not bothering with maintenance.

Leadership at PG&E has milked the company for every dollar by failing to properly maintain or replace it’s infrastructure. This is a maintenance philosophy called “run to failure”. Engineering at our company had to beat back similar management efforts some years back in our factories letting management know that it was 1) often illegal, 2) could likely injure or kill personnel, and 3) would adversely impact production. It was only with much effort that we talked management back off the ledge on that one.

What California is experiencing with PG&E is a deliberate policy of neglect to enhance management income.

Also, solar/wind can store energy via hydrogen/methane generation. IMO methane generation is the most viable way forward, as methane-driven cars mean relatively small changes to the existing infrastructure. In continental Europe, CPG cars are not uncommon already, with the infrastructure to fuel them and all. Most of the gas station in my neighborhood have CPG refuelling facilities as well as the standard stuff.

Given that CPG is, optimally, all methane…

The above article makes a big assumption: that we want to, or get to, keep the current global economic system.

should be

Historically, much of human activity functioned without fossil fuels and will inevitably reconfigure into a form without them. This will take place over a longer period than the word “collapse” implies and the conclusion is more accurately stated as:

However, if the author, like myself, is used to a Western middle-class life then the decline ahead will appear like collapse on the personal level. I work in computers, which I find fascinating, but I am very aware of how complex and fragile the industrial system is that makes them. Further, when energy, resources and money become constrained, it’s hard to see how the computer/gadget industry can continue as is. Everything is digital now, especially communications. Returning back to the old analog telecommunications may not be feasible at its previous scale. Radio may be the one that can. But when the Internet declines can the old television broadcasts return? Decline will not be evenly distributed, of course, but countries that do not have silicon foundries may not be able to maintain digital technology at all as imports grow scarce. I take some comfort that Science Fiction is more optimistic, imagining a future where wind-driven clipper ships transport nano-tech across the oceans.

True. But would you want to live like that? Human history is littered with periodic famines across Europe and probably most of world once it relied on agriculture and population densities grew too large to return to previous lifestyles. The advent of industrial agriculture which relies on fossil fuels largely eliminated famines, and the relatively recent advent of plastics from oil made life vastly easier for billions of us. The long-term consequences are appalling, obviously, but that’s a problem to solve.

Plus ça change…

We might not want to live like that, but that’s because we’ve tasted the wonders of industrialization. On the other hand, the people living during the 1600s or anytime in the past probably never expected life to get dramatically “better” let alone our current way of life. Some of them probably learned to be content with what they had. Is that bad?

Yes, and there would not currently be billions of people on this planet had humans not been able to thrive without fossil fuels.

Some charts to consider in that regard (I don’t vouch for the sites or their backers, just the graphs as evidenced by their labels);

1) World population growth (scroll down)

2) World energy consumption (scroll down)

And finally, the Limits to Growth chart. Scroll down to where you see four graphs. Note the population curve.

So, it appears from the graphs that population growth in sub-Saharan Africa is greatest in an area with minimal fossil fuel consumption. The charts show that the effective fertility rate in Nigeria is 6.2 while in South Korea it is 1.2. It seems that population control is best implemented in a culturally cohesive, industrially advanced, educated population. Whooda thunk it.

Or it could simply be increasing cost of living + stagnant wages. In poor countries like Nigeria, there’s no guarantee any given child will grow to see the age of 10 (just a guess). China used to be like that too.

Speaking of energy consumption. When is an appropriate time to take Bitcoin out the back with a rifle in hand?

Bitcoin energy usage is insane. It produces nothing, it epitomises what is wrong with our financial markets.

Yes this is 100% truth. What a waste of natural resources – all to produce something with literally zero intrinsic value.

Notice how Wall St. never has to “take one for the team.”

Where are the progressives to call for banning mining as a climate provision in the BBB bill that keeps on shrinking?

I agree and have a few additions to the list:

1) private planes and helicopters*

2) fast food restaurants**

* cold turkey, close down the factories and melt down existing craft

** phased (Why should we allow this “industry” to destroy both the environment and their customers’ health? Oh, I know. Jawbs. And such very fine jawbs they are.)

We would need a program of Universal Basic Income and Federal Job Guarantee both combined at the same time and ready to go in order to have something to offer to the jawbholders in returning for firing their jawbs. Without the pre-engineered ready-to-go high credibility promise of those two things ready and waiting for them upon the loss of their jawbs, they will not submit quietly to losing their jawbs in a great Bonfire of the Jawbs.

I don’t have time to get into the details of this post, and perhaps I’m misreading some of the arguments, but I think a number of Tverbergs assumptions are simply incorrect and out of date. We’ve seen enormous changes in the economies of power generation and supply over the past 10 years, this simply isn’t reflected in her writings now. The price of solar and wind has dropped enormously and is now the cheapest option for new electrical power capacity. The notion that the major industrial economies cannot replace existing electrical power generation with non-fossil fuel over the usual investment lifespan of 20-25 years is simply untrue, and I don’t think there are any serious analysts outside of the fossil fuel industry who believe that. The problems are political and institutional. She is also flat our wrong to suggest that somehow ‘economists’ have been telling Europe that they don’t have to invest in fossil fuels, I’ve no idea where she gets this idea. In reality, Europe has been spending billions in trying to widen its access to natural gas from a variety of sources, plus countless billions in developing nuclear reactors (the latter of which have been a disaster).

As for the issue of ‘complexity’, I don’t really understand the point she is trying to make. Complex systems are, like complex ecosystems, inherently more robust than simple ones. Energy systems with a variety of sources and an historic overlay of infrastructure tend, in general, to be stronger and more robust than those dependent on single source, or having a single generation of infrastructure. The ‘complexity’ has been introduced through long and needlessly complex supply chains, but Europe in particular has always been highly dependent on external supplies of energy (just read some WWII history to see just how crucial this was to military decision making). What does seem to be a problem now is that energy sources have become more intertwined than was the case in the past, hence we are seeing cascading problems linking wind, coal, gas and oil supplies. Even nuclear reactors are facing shut downs due to problems with gas supply for back up generators.

Another questionable assertion is that economic development is inherently tied to energy use. There are obvious connections, but historically speaking its not as tight as suggested. If this was so, then North Korea, with all its coal, would be a lot richer than South Korea, which has almost no domestic form of cheap energy. For that matter, if energy was crucial, South Korea would most certainly not be the third largest manufacturer in the world. Likewise, Japan developed rapidly with little to no access to cheap energy. Germany has for decades has had some of the most expensive domestic energy in the world, and it hasn’t exactly harmed its industrial development.

Much more important than energy, by far, in economic development is the management of land and the agricultural production.

Yes! It is the overpopulation of sub-Sahan Africa that will impact local land management (ecosystems/poaching) and the need to expand agriculture into unfavorable locations (forests) that will create problems.

Also, the mass monopolization of land by Industrial Scale Plantationeers all over Africa will also impact local land management, and will impose land-shortage upon the local population by large scale land grabbing and enclosurization long before overpopulation ever does.

“ The notion that the major industrial economies cannot replace existing electrical power generation with non-fossil fuel over the usual investment lifespan of 20-25 years is simply untrue, and I don’t think there are any serious analysts outside of the fossil fuel industry who believe that.”

Yes. Thank you. Most arguments against our transition to renewable energy are simply hogwash. Spiced with upper middle class petulance about “excessive” new development, damage to scenery, and an ill-concealed desire to see a large part of the world’s population simply die off. Somehow. The mechanics of this Return to Eden by way of rapid decline in population are rarely discussed, and never discussed honestly.

Thanks for this, Yves, and a great introduction to an excellent example of a particular kind of thinking.

I’ve been reading a lot of business- and economics-related material lately because of my involvement in the Common Earth course–more than at any point since college. Yves’s criticism of Tverberg provides a good starting point for something I’m seeing in this reading that is worth discussing in my view.

Yves notes this in her introduction:

Yves then goes on to recount a little of the history of the rise of neoliberalism and its impacts on complexity independent of energy prices or availability.

And Yves is right. Just as she dissected the ’08 crisis in Econned in a way that made it comprehensible to the laity, she sees through Tverberg’s overly simplistic understanding of the rise of complexity and provides a detailed explanation of why it falls short. She can do this because she has operated inside these systems, sat around the table, after being thoroughly trained to do just that.

Stephanie Kelton is much the same. She writes The Deficit Myth after serving as Sanders’s aide on the Senate Budget Committee. She’s talked to the members and their staffs. She’s knows their thought processes, and she takes apart their mistaken ways of thinking piece by piece. Kelton, like Yves, brings the expertise and nuanced thinking of an “Inside” point of view.

Tverberg comes from an “Outside” perspective. Those coming from the “Outside” perspective, like Meadows, Tverberg, Heinberg or Raworth, start far from the “Inside” framework. They begin with the idea that the economy is embedded in the natural world and subject to any limits it imposes. Note Tverberg’s graphs. How many of them relate directly to the natural world and its “resources?” The sloppiness about the history of the rise of Thatcher and Reagan, and the tendency to explain everything in terms of the limits to growth is pretty typical of those coming from the “Outside” perspective.

Both kinds of thinking are desperately needed today. “Inside” thinkers can neglect to consider the natural world because they’re living inside a world, whether it’s Wall Street or Capitol Hill, that largely ignores the natural world. Kelton’s book struck me as weak on our little carbon problem, especially in the way it talks about growth without considering its consequences and given when it was written, but I have to wonder if Kelton realized that adding growth limits to her book would make it completely unpalatable to those she is very seriously trying to persuade, including right now in these days of Manchin and Sinema.

And we’ve already seen, thanks to Yves, how the “Outside” perspective of Tverberg can be blind to the intricacies that the “Insiders” consider to be almost common knowledge.

The last chapter of Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics does a somewhat better job of handling both the “Outside” and “Inside” points of view. She begins with the Kennedy Administration and Walt Rostow’s Five Stages of Growth proposed in the 60s as a model for the developing world. It begins with traditional society mired in the misery of life without TV dinners and “Bonanza” in color and lays out 3 steps “forward:” pre-flight; take-off and climb to altitude. Step 5 is to keep on flying, as Handel would say: forever and ever. Walt was apparently relying on the in-flight refueling planes they built to keep the B-52s in the air to keep that economic bird in the air forever. You can see how that might set someone with the “Outside” perspective into a tizzy.

Raworth then divides the world that gives a damn into two factions: those who believe that plane can keep flying forever and those who want to figure out how to land it safely.

She then moves on to curves of three types. The first is the exponential growth curve. That’s what we’re on if growth is to continue forever. It makes the whole idea look pretty silly. The second type of curve is the Seneca Curve highlighted by Tverberg. You could also all it an Overshoot Curve because that’s what a graph looks like when a species becomes overpopulated to the point that it exhausts the resources it requires. The third type of curve is the S-curve. It rises like the exponential curve to a certain point, then bends around to fit under a straight line ad infinitum. This, Raworth says, is a way to land the plane.

She goes on to discuss several other “Outside” points. The keep-on-flying advocates claim that “decoupling” will break the link between GDP growth and carbon emissions. Raworth responds by showing that both technological and economic feasibility are questionable, and studies published since Doughnut Economics was written in Nature and elsewhere make the point even more strongly. She also talks about the drop in Energy Return On Investment for all currently used forms of energy from new oil wells, to secondary and tertiary recovery in old wells to wind and solar to nukes.

So far, all this has been textbook “Outside” thinking. But then Raworth acknowledges that we are living in a world where the people in charge fervently believe that economic growth is essential to our civilization. She argues that we’re addicted in three areas: finance; politics (the scariest one); and socially (we could say culturally here). It’s great that she recognizes these impediments to change, but I would love to hear what Yves has to say about an addiction to growth in finance. I’m sure there’s a lot more depth to the topic than Raworth, who’s a development economist who’s worked with the UN, is qualified to provide.

We’re in desperate need of lots of good thinking. I’d like to see the “Inside” and “Outside” perspectives work together, fill in each other’s weak spots and produce compelling ideas that will help us land that plane.

Now I’ve walked way out on that limb. Saw away.

No saw here. Love your observations.

Intermittent is a relative term. If you’r looking at way the two century fossil fuel economy operates, the idea of simply plugging in renewables to take their place was always wrong. It’s about building a new economy based on the energy renewables provide. The economy needs to and will change in every way, cheap oil is over, and no economy on the planet is more dependent on cheap oil than the USofA. Cheap oil’s demise wasn’t so complex that it could be covered up with debt for a few decades. What’s that about bankruptcy, gradually than all at once.

Life is a complex system, we don’t do complexity well at this point, we still don’t understand life.

“Life is a complex system, we don’t do complexity well at this point, we still don’t understand life.”

Fritjof Capra, along with co-author Pier Luigi Luisi, have done something about that: The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision. It’s designed as a college textbook. I actually bought it and am using it as a reference.

Here’s a dialogue with Capra about the book along with, of course, some discussion of the Tao of Physics.

A lot of her prescriptions seem to fall under the heading “be nicer to fossil fuels”, both fuel suppliers and fossil-based electricity generators.

Provide them with predictable, long-term high prices, pay their capex upfront, shield them from competition, be polically pliable to suppliers, don’t develop alternatives, don’t try to improve efficiency.

That might indeed be good strategy in the medium term, if the overriding aim is to have to have steady supply of fossil fuels without price spikes. But it would be a dead end in the long term, as I see it.

Climate change is the obvious problem, though Tverberg seems to consider energy supply as more important. Even purely looking at energy supply, we still need to wean ourselves from fossil fuels at some point.

I try not to talk about this stuff with anyone in my life. It makes me feel crazy.

In particular, what is occurring in China fills me with curiosity. Some people know about the rolling black outs in China. What most don’t understand though is that the factories are shutting down. Not all of them, and not all the time. But they are going offline. Chinas factories and their labor force have had a massive deflationary affect on the United States over the last few decades. And that deflation has been a source of social stability. The Chapotraphouse kids call it The Treat Economy – in that all the cheap junk that keeps us entertained is the only thing that has been soothing the American people since the economic restructuring post-2008. If China is shutting down factories, the deflation and thus the treats are going away too. Ultimately I think it is a good thing. American consumption needs to end. But what is an American if not a consumer, and what happens when the consumer cannot get their treats? Just look at any number of videos online of an entitled schmuck being told they can’t get their treat. Consumption is a cancer on society, and we’re all about to get chemotherapy. It’s probably going to hurt. I just wonder whether the patient will make it.

Indeed, what is the point of making stuff in China to have it float on the water for a year? The confluence of factors causing the unloading of ships be reduced to one third their previous pace is like someone stepping on their own air supply and being unable to get off.

In gearhead terms, the engine was over revved right when it experienced a lean condition, and pre ignition, commonly known as detonation is happening in most of the cylinders. Piston, connecting rod and crank failure will occur within the next couple of revolutions. Ignition timing doesn’t even matter anymore.

the article was pathetic in many cases, worrying about china’s exports. how many tons of fossil fuels have been burned up way ahead of its time shipping and flying stuff all over the world under free trade, just to save a penny in production here, and a penny there, which all goes into the pockets of a few parasites, to the detriment of the worlds population and environment.

how much fossil fuel is burned shipping from chicago to minneapolis?

how much fossil fuel is burned shipping from china, to chicago, then to minneapolis?

this has been going on since 1993 under nafta billy clintons free trade. it super charged climate change, and drained the world of decades of fuel prematurely.

we could go a long ways into cutting fuel consumption by just making it local, and much shorter shipping range.

Moving production of things from America to Mexico, China, Bangla Desh, etc. etc. was very destabilizing to everyone who lost those shipped-out jobs, and everyone related to them, and their communities and etc. Any cheap China crap coming back as a booby prize might have soothed people but didn’t stabilize the people destabilized by mass jobicide and mass job export.

So what is this stabilization I read about “being provided” by all the cheap plastic stuff at the cheap end of the production import stream?

What if what is really happening is that we are reaching ‘The Limits to Growth?’ I see all those suggestions listed for dealing with rising energy prices but I doubt that they are real solutions. Through cheap energy, we were able to squander it to structure our economy in totally inefficient ways that was hidden by the fact that it was organized as tight as a drum. An example I read about once was the simple nylon t-shirt. This article was showing how after the original oil was extracted, that each stage from turning it into nylon, from sending it to a cheap place to turn it into clothing to be shipped to the other side of the planet for sale and eventually to be shipped to another cheap place for disposal was mind-boggling. The energy squandered in manufacturing this t-shirt and shipping it to different paces around the world for each stage was just insane but cheap energy made this system possible. Those days are coming to a close thankfully but the changes that we will have to make in our lives as a consequence will be massive as they will be inevitable-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Limits_to_Growth

About 10 days ago there was an energy entry on NC that got a lot of commentary, but it hinged on the notion that the non-carbon energy sources set to replace fossil fuel were already cheaper than fossil fuel and expected to keep growing that advantage. But many of the comments seemed to say that energy usage ought to contract pretty significantly anyway. Why get excited about t-shirt product-cycle energy consumption if clean energy is going to be cheaper?

This article didn’t include some key points:

a. Financial resources lavished on the fracking industry were not “reliable”. They were massive till they weren’t. The fin industry’s job is to allocate fin resources for highest societal benefit. How are they doing?

b. Complexity. We’re overhauling our entire auto fleet, transitioning from internal combustion engines to electric motors, which constitutes a vast reduction in complexity, not just for the vehicle but for the supply chain that produces and operates that vehicle.

c. The supply-chain issues we’re experiencing now are primarily the result of Covid interference in normal organizational ops, and then massive stimulus injected directly into consumption, putting huge addnl load on organizations that are already impaired. These organizations didn’t suddenly get more complex – they were working fairly well until they got whacked via externalities. Should we add some buffer – e.g. larger warehouses with excess stock? Sure, but that’s not cost-free, is it? Does Tverberg address those costs? Did she mention that our ports are clogged because we have continuous, record-breaking trade deficits with China, lately fueled by massive consumer-directed stimulus? Those major causative factors didn’t get mentioned.

d. If “reliability” is the desired goal, is it better to continue to resource fossil fuels (keep price above production costs) or it is better to invest in tech that addresses the variability issues of wind and solar? Which holds greater promise for long-term stability? Where’s the finance industry on this topic?

f. Automation and supply-chain management are disciplines whose function is to wring out excess, and one of the best ways to do that is to eliminate components and tasks which add cost/complexity without adding compensatory value. There are legions of well-trained professionals who are dedicated to the subject, world-wide, 24×7. Their activities reduce complexity, not add it.

g. Energy price-spikes are an artifact, principally, of financial market interference and distortion. That point Ms. Tverberg makes, and it bears repeating. A great deal of our economic distortions and mal-investment can be laid squarely at the doorstep of our vaunted Financial Sector, that fabulous and gifted allocator of capital we’re so richly blessed with.

h. We are transitioning, very awkwardly, away from fossil fuels. The automobile industry is doing its part. There is currently insufficient renewable energy capacity to shoulder the emergent electricity burden that will occur as we transition to electric vehicles. That is the problem; complexity isn’t the problem. We are missing key technologies (solar panels that don’t use rare materials, electrical energy storage mechanisms, for example) that need to be invented, tested, and implemented. That’s where the work is, and that’s where the national attention and capital investment should also be. We also have a huge political problem: the transition away from fossil fuels is making some rich people less rich, and so, using the Manchins of the world as sand in the gears, they resist. We have fin allocation, tech development and political obstruction by rich people to overcome.

And none of the foregoing is new, or surprising. The auto industry has taken note, and is doing its part. Now it’s up to the fin and tech and political industries to do their part.

Complexity….bah.

I’ll just leave this here

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_usage_of_the_United_States_military

Our current economic system relies heavily on the ability to hide the true costs associated with its operations.

The true cost of transportation involved in our supply chains is currently becoming clear.

The principal hidden cost that needs to be examined is the cost of de-industrialization that would leave the USA a nation of paupers working for McDonalds and shopping at the Dollar store.

So far, shipping America’s jobs to China has been sold as the operation of ‘natural’ forces inherent to economic systems, and unavoidable because of the ‘negative’ results of power being shared between Labor and Capital.

Capital has succeeded in sweeping the runway clear of all impediments to ‘growth‘, in large part by purchasing our government on the one hand, and hiding the cost of those things which they consider ‘externalities‘.

Right now, this very instant, We the People are learning that we must struggle to afford our rights to Life, Liberty and any sort of Happiness, largely because the cost of those rights has been hidden from us so as to allow for their sale to the highest bidder.

The very biggest problem facing the American working class is that so far, the rich and powerful who have led us down this dead-end path have succeeded in convincing half of us that it is other poor, working class people who are to blame for our misery.

One could be forgiven for thinking that the 1% are warning us about the dangers of inflation, allegedly due to enacting widely beneficial social policies, when in reality, they are trying to hide the looming cost of actual, existing inflation, due to the immense amount of ‘Free Money‘ pumped into the economy by QE to their benefit, and at their direction, and incidentally, resulting in the rest of us being driven from our homes, the inevitable result of their massive investing in real estate.

One could also be forgiven for thinking that the 1% are looking forward to making a lot of money in the coming Civil War economy.

Well said, Watt4Bob.

Now, what to do? Do we get angry and then do nothing about it, or do we convert that rage into effective action?

What actions would be effective? Do we:

a. “Revolt” by conducting violent warfare against these “elites”?

b. “Revolt” by slowly, incrementally, and continually building a new economy that – one design, one new product, one purchase decision at a time – bypasses / marginalizes these helpful “elites”?

There’s one other big problem that you didn’t mention, but I’m sure you’re aware of, and that is the relentless march of automation, and the concurrent reduction in the value of labor. While the “elites” didn’t help laborers much, the biggest, most durable and consequential reason for the impoverishment of labor – worldwide – is automation.

That needs to be faced up to. After we “got rid of them stinkin’ elites”, we’d still have the automation problem. Socialist, communist, capitalist or blend, all the “isms” have that problem. All of them, and the effect is the same.

Sorry Tom, I don’t buy the whole ‘Automation Problem’.

Even the New York Times has bailed on that excuse.

If Automation were the issue, there would be evidence of an increasing trend in investment in automation.

This is not the case.

From the Economic Policy Institute;

The numbers to back this up are at the link.

That “unbalanced globalization” thing is biting us on the back-side something fierce at the moment, illustrating the fragile nature of the supply chains we’ve constructed.

I’d ask people to understand that all those ships waiting off-shore at America’s ports, and the stuff they are carrying, are tied to production at factories, and by extension to jobs that now exist in other countries, but used to be right here in the USA.

You ask;

I don’t know, but I’m sure that the first step is being honest about where we’re at, and the way we got here;

1. We’ve allowed Corporate interests to stamp out labor unions.

2. We’ve allowed the rich to dodge their civic responsibilities, especially as concerns paying their fair share of taxes.

3. We’ve bailed-out the investor class at every turn when they’ve faced economic ruin because of their bad choices.

4. We’ve allowed for the concentration of communications media to the point where the American people read, and hear nothing but pro-business propaganda 24/7/365.

5. We’re currently invited by that propaganda system, in a clear effort to divide and conquer, to believe that our problems are the result of the actions and behaviors of ‘The Other‘. The other being the portion of the working class that doesn’t look like you, or love like you, or worship like you.

All of this nasty effort on the part of the rich and powerful being incredibly ironic because all monies received by the working class, meander up-ward to the rich anyway.

The difference being that on its way to the rich’s pockets, money applied at the bottom of the economy does a lot of good for a lot of people, while money applied to the top does relatively little for anyone, including the rich.

Ask Jeff Bezos what additional benefit his latest $Billion provided him, other than bragging rights.

Watt4Bob:

Depending upon the NYT for technical info is not always a great idea.

Points 1-5 above I agree with. Your assertion that automation isn’t a factor in wage reductions, outsourcing, job loss, etc. I decidedly do not agree with.

Let’s do a little thought experiment: Assume that productivity increases average about 2% per year over a period of 20 years. That’s been about the average here in the U.S. over the past 40 years. Data’s from St. Louis Fed

How many workers are required to produce the same output after 20 years of 2% productivity increase, compounded annually? (the data source is for labor productivity).

The answer is “about half”. Every 20 years we need half the workers to produce the same output.

Automation isn’t just robots. It’s better tools, simpler processes, self-checkout, unmanned tool-booths, object-oriented software, computer on every desk, e-mail, software doing what humans once did…it’s all those productivity improvements which technology – “what humans know how to do” – increases each year. Most of those increases in what humans know how to do, in the business realm, are about getting more done with less labor. Labor has a great big target on its back; it’s expensive, and it’s the most readily eliminated of production inputs. It’s not nice, but it’s a fact.

Think about that. Every 20 years, approximately, we only need half the workers to produce the same output. We’d have to consume 100% more every 20 years in order to keep everyone fully employed. Do you wonder why we’re constantly programmed to buy, buy, buy? It’s not just to make Ritchie Rich richer. It’s to keep you and I employed.

Labor is getting increasingly wrung out of the production equation. It’s been going on forever, and it’s accelerating. That is the main reason labor is getting stepped upon. No pricing power.

Ah, but Unions! I say “great! Go for it.” Labor bargaining power is a good thing, and it’ll help. It’ll slow down but nowhere near stop the exit of labor from large-scale production. Not happening. Move factories back from China! Great again. Will the factories be more or less automated than they were when they left in the 80s and 90s? What’s your guess?

So, I agree with the sentiment, and most of the facts of your remarks above. I don’t agree at all that automation isn’t a factor in job loss. It’s the main factor, has been for a long time, will be for a longer time.

Please refute the data I linked to, or the calculations I used to compute how many jobs are eliminated every 20 years by productivity increase.

Everyday you see automation transfering work back to the consumer. For example, phone automation makes you select choices when you make a call. As you go thru the options to select the one you want you are wasting your time while the corporations decrease the amount of labor involved (smartly card productivity by them) and bucks it to you. There are so many examples of this tranferance in daily life – paying bills on the web, getting questions answered by a robotic assistant etc. etc. Self check at the store is another example. The eliminate labor and transfer the work to the consumer.

yes. Another great technique for corporate efficiency’s sake…at your expense. Understand, I’m not vilifying corporate types. Pick-your-own farms transfer the picking function to the consumer, right?

The point I’m trying to make is that these efficiency gambits are part and parcel of folks trying to get ahead. It’s endemic to the human species – it’s what we’ve done since day 0.

Since it’s durable, and endemic, and therefore something of a fact of life, maybe we should see it as such, and start asking fundamental questions like “if we’re all busy eliminating labor from our production processes, what on earth do we do once we’ve succeeded?”.

Things are moving a bit faster than we’re adapting, and that change-adaptation mismatch is playing havoc with us. We’re not ready for all this. I can’t say “nobody’s ready”, but I can surely say “most of us – the vast majority – are nowhere near ready to cope with – here it is now – what already is”.

Already is. It’s here.

Pick-your-own farms allow the “consumer” to excercise his/her own quality-control in deciding what to pick. A number of pick-your-own customer-clients also regard it as a partial-day working vacation.

So that is different than robo-checkout at the grocery store.

What happens to automation when energy to drive the automatic machines runs short and then runs shorter?

Most of us starve is what happens, or we kill one another and then those left starve.

I’m not yet convinced that “energy’s going to run out”. If it does, we’re going to have way bigger problems than “can’t run the grain mill, no power”.

Society isn’t going to devolve gracefully if “energy runs out”. My vote is to make sure that doesn’t happen.

And there are many ways to make sure it doesn’t.

I didn’t say “run out”. I said ” runs short and then runs shorter”.

Hopefully energy will run short enough slowly enough that the employer class is forced to re-hire people to perform work for pay instead of semi-starving under bridges and behind dumpsters before we reach a state of general collapse which would happen if energy runs short too fast for us to keep up.

The process you are describing is productivity increase. That’s not the problem. The problem is that productivity increases have become decoupled from wage increases.

Automation isn’t the problem — who will own the automation is the problem.

“Automation isn’t the problem — who will own the automation is the problem”

That’s the conclusion I was looking for.

I think “the way out” of the automation crush is to make access to, ownership of, operation of, full comfort with … automation way more common, top to bottom of social-economic spectra.

Way easier said than done, but I think this is a durable solution.

I wonder if people will just go back to doing business with each other and cooperating on the local level when there is no ‘invisible hand of the market’ scaring everyone into a state of zombieism. Where I live, there is a lot of cottage industry. People will ‘gig’ for themselves and their neighbors again, and it will adjust to the local ability to pay. I am not saying that outside goods won’t be needed, but the beef I buy from a farm a mile down the road is grass-fed–I pay no more for it than I did a year and a half ago. Corn and hay and beans are prevalent crops. Goat and bovine dairies abound, I get free-range eggs, and CSAs are proliferating. Gas prices are terrible, but I ride an electric bike. Electricity has been transitioning to solar for years and costs are kept down. The elderly get a RE tax rebate so we won’t be taxed out of our homes. What the elites are really worried about is that we really don’t need them at all once we have time to get our strength back from being flogged to death in shit jobs. That’s why they are buying up all the property–they have no skills or desire to work so they have to rentier to stay dominant. Once they can’t steal, they are finished. They really have no control at all, but the MSM is paid billions to make us think we are helpless. it’s not going to be sustainable.

More power to you.

I wish I’d read your post sooner. I’m trying to do what you’re doing, and I’ve long since adopted your philosophy and strategy.

And it’s been hard. Farming – my new job – is waaaayyy tougher than the cushy, simple, predictable and well-paid job I worked in I.T. for all those years.

And yes, that is mostly why the “elites” are buying up property. The other reason is that the buying power of the dollar is falling and will continue to fall. Trading dollars for land is a great move right now. For anyone, not just the rich.

I think you’re on a great track, Helena. Thx for reporting in.

Best wishes for your farm! I did landscaping/nursery work for many years and compared to my other jobs, I felt very good about it. It did take a different toll on my body, but fed my spirit. Take good care of yourself. I’m hoping your community supports your endeavors. I specifically moved to where I am after seeing this lifestyle could be supported and bought my home here. There’s all kinds of ‘hard’ and we are working for healthy rewards, so that’s what matters.

Blogs (like this and others) can be part of a counter-MSM true-news infrastructure used for carrying inspiration and information about the re-skilling and up-skilling of non-elite people so they ( we) can learn to evade their moneyconomic tollbooths and coin-operated bottlenecks and turnstiles. People can start spreading general news and specific information all over the counter-MSM about the theory and practice of non-helplessness, at least until the various counter-MSM venues go dark. Which won’t matter if all the survivalist information has already been spread far and wide.

100%!

When I was a kid it was common to hear what this article is saying–that America’s great wealth was the result of our abundant natural resources with oil, especially, at the top of the list. Some might even say the “exceptional nation” mentality stemmed from this bounty and our protective oceans that provided self sufficiency. Trump’s “make America great again” was itself a futile cry based on the notion that we can somehow hop in a time machine and return to a time with far fewer people (therefore immigration a key concern) and far more resources.

Of course we can’t do that but the above seems as good an explanation for now as any. Meanwhile countries like China are imitating our growth above all rise in a world that is threatened by growth’s externalities. In the future “wealth” may be an idea that is past its sell by date.

I agree. We all need to downsize our lives; especially those of us who live in so-called advanced economies. We need to make less, consume less, aspire to less, envy less, work less, be less in a material sense. Satisfy our needs? Yes. Our wants and desires? Absolutely not.

Or learn to want and desire only our needs.

Its the revolution of falling expectations.