Yves here. Hollywood has occasionally tried to bring the evolution of military technologies into its action flicks. For instance, I dimly recall someone in Braveheart saying no one had beaten an onslaught of heavy horse in hundreds of years (and the of course Richard the Bruce does just that). But I hadn’t worked out the degree to which advances in offensive technologies led to innovations in defenses (as opposed to higher walls, deeper moats, and better food stores).

By Peter Turchin, Professor of Evolutionary Anthropology, University of Connecticut. Originally published at The Conversation

Starting around 3,000 years ago, a wave of innovation began to sweep through human societies around the globe. For the next millennium the continued emergence of new technologies had a dramatic effect on the course of human history.

This era saw the advancement of the ability to control horses with bit and bridle, the spread of iron-working techniques through Eurasia that led to hardier and cheaper weapons and armor and new ways of killing from a distance, such as with crossbows and catapults. On the whole, warfare became much more deadly.

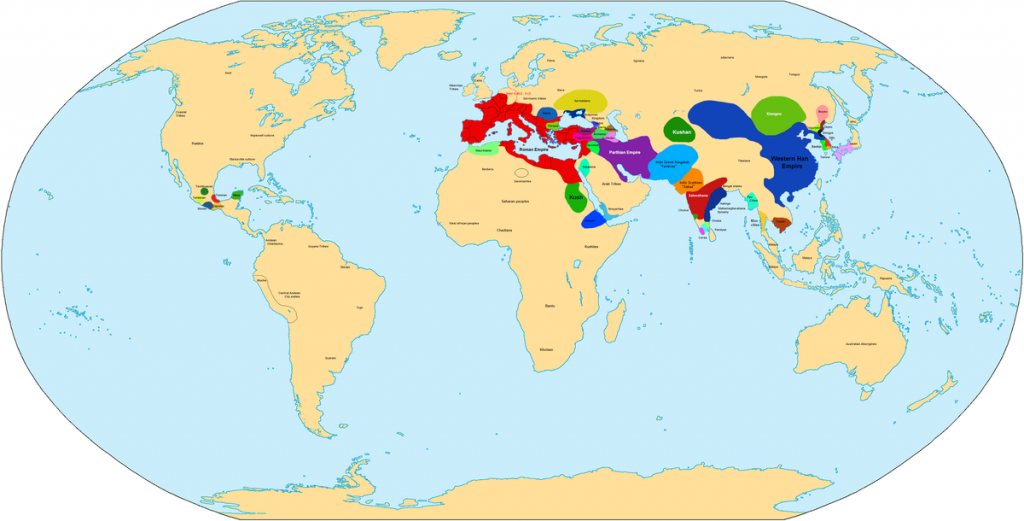

During this era, many societies were consumed by the crucible of war. A few, though – the Achaemenid Persian Empire, the Roman Empire and Han China – not only survived, but thrived, becoming megaempires encompassing tens of millions of people and controlling territories of millions of square miles.

So what drove this cascade of technological innovation that literally changed the course of history?

We are a complexity scientist, Peter Turchin, and a historian, Dan Hoyer, who have been working since 2011 with a multidisciplinary team to build and analyze a large database of past societies. In a new paper published in PLOS One on Oct. 20, 2021, we describe the main societal drivers of ancient military innovation and how these new technologies changed empires.

A Database for Human History

The store of knowledge about the past is truly enormous. The trick is to translate that knowledge into data that can be analyzed. This is where Seshat comes in.

The Seshat Databank is named after Seshat, an ancient Egyptian goddess of wisdom, knowledge and writing. Founded in 2011 as a collaboration among the Evolution Institute, the Complexity Science Hub Vienna, the University of Oxford and many others, Seshat aimed to first systematically gather as much knowledge about humanity’s shared past as possible. Then our team formatted that information in a way that allows researchers to use big-data analytics to look for recurrent patterns in history and test the many theories aiming to explain such patterns.

The first step in this process was to develop a conceptual scheme for coding historical information ranging from military technology to the size and shape of states to the nature of ritual and religion. The database includes over 400 societies across all world regions and ranges in time from roughly 10,000 B.C. to A.D. 1800.

In order to trace the evolution of military technologies, we first broke them down into six key dimensions: hand-held weapons, projectiles, armor, fortifications, transport animals and metallurgical advances. Each of these dimensions was then further divided into more specific categories. Altogether we identified 46 such variables among the six technological dimensions.

For example, we distinguish types of projectile weapons into slings, simple bows, compound bows, crossbows and so on. We then coded whether or not each historical society in the Seshat sample wielded these technologies. For example, the earliest appearance of crossbows in our database is around 400 B.C. in China.

Of course, humanity’s knowledge of the past is imprecise. Historians may not know the exact year crossbows first appeared in a particular region. But imprecision in a few cases is not a serious problem given the staggering amount of information in the database and when the goal is to discover macrolevel patterns across thousands of years of history.

Competition and Exchange Drive Innovation

In our new paper, we wanted to find out what drove the invention and adoption of increasingly advanced military technologies around the globe during the era of ancient megaempires.

Utilizing the massive amount of historical information collected by the Seshat team, we ran a suite of statistical analyses to trace how, where and when these technologies evolved and what factors seemed to have had the largest influence in these processes.

We found that the major drivers of technological innovation did not have to do with attributes of states themselves, like population size or the sophistication of a governance. Rather, the biggest drivers of innovation appear to be the overall world population at any given time, increasing connectivity among large states – along with the competition that such connections brought – and a few fundamental technological advances that set off a cascade of subsequent innovations.

Let’s illustrate these dynamics with a specific example. Around 1000 B.C., nomadic herders in the steppes north of the Black Sea invented the bit and bridle to better control horses when riding them. They combined this technology with a powerful recurved bow and iron arrowheads to deadly effect. Horse archers became the weapon of mass destruction of the ancient world. Shortly after 1000 B.C., thousands of metal bits suddenly appeared and spread within the Eurasian steppes.

Competition and connection then grew between the nomadic people and the larger settled states. Because it was hard for farming societies to resist these mounted warriors, they were forced to develop new armor and weapons like the crossbow. These states also had to build large infantry armies and mobilize more of their populations toward such collective efforts as maintaining defenses and producing and distributing enough goods to keep everyone fed. This spurred the development of increasingly complex administrative systems to manage all these moving parts. Ideological innovations – such as the major world religions of today – were also developed as they helped to unite larger and more disparate populations toward common purpose.

Within this cascade of innovation we see the origins of the world’s first megaempires as well as the rise and spread of world religions practiced by billions of people today. In a way, these critical developments can all be traced back to the development of the bit and bridle, which allowed riders better control of horses. Each step in this line has been long understood, but by employing the full range of cross-cultural information stored in the Seshat databank, our team was able to trace the dynamic sequence tying all these different developments together.

Of course, this account gives a greatly simplified explanation of very complex historical dynamics. But our research exposes the key role played by the intersocietal competition and exchange in the evolution both of technology and of complex societies. Although the focus of this research was on the ancient and medieval periods, the gunpowder-triggered military revolution had analogous effects in the modern era.

Perhaps most importantly, our research shows that history is not “just one damn thing after another” – there are indeed discernible causal patterns and empirical regularities through the course of history. And with Seshat, researchers can use the knowledge amassed by historians to separate theories that are supported by data from those that are not.

This story was co-authored by Daniel Hoyer, a researcher and project manager at the Evolution Institute and a part-time professor at George Brown College.

There is very little new in this analysis – the role of the bridle and bit and stirrup in aiding mobile societies has been known for a very long time and well studied (because they usually are well preserved in the archaeological record). The breeding of larger horses over time was also important – previously societies used chariots, which were very effective in very specific circumstances (lots of nice flat, hard, ground).

The role of horses in historical warfare though has always been hugely exaggerated. The horse was for much of history a status symbol for aristocratic elites, not military game changer. The Greeks and Romans did fine without making much use of cavalry. They just hired housebound ancillaries when they deemed it necessary, and plenty of times they didn’t see it as necessary. Horsebound societies like the people of the Steppes usually only managed conquests when they worked out how to do boring things like siege warfare and building defence structures. Horses provide tremendous mobility and speed on flat ground (which is why they were always used for flanking movements), but in up close warfare they are very vulnerable to any enemy with a blade on a stick who doesn’t lose his nerve on first contact (as its very well portrayed in Braveheart).

Military technology has very rarely been a real game-changer in history. Any re-enactor will tell you that many so called military breakthroughs (such as crossbows) are a loss less useful in reality than they seem in history books or video games. The biggest impact military tech has is when a society with one particular weapon happens to hit upon a society that has never seen that weapon before and doesn’t have the time to work out how to deal with it (the Normans were particularly good at exaggerating the small military advantages they had by identifying weak societies). Wars are won through organisation, aggression, and (usually) raw numbers, not fancy weapons.

Yes, I was going to make the same point. I was reading through the article thinking, “what’s new about this, then?” There are any number of histories of military technology already, and of course there is Charles Tilley’s famous comment that “states made war and war made states” which sums up much of this article.

The technology and organisational of warfare is very much a scissors-stone-paper phenomenon, and much depends on the precise balance of technology and organisation between combatants at the time: these balances can and do change quite quickly. For example, by the time of Agincourt (1415) armour designers had already worked out how to defeat longbow arrows, and re-enactments have shown that they were relatively ineffective: the English victory turns out to be a lot more complicated than was previously thought. History is full of cases where the winning side has no advantages of numbers or technology, but still wins a smashing victory (France in 1940 is the classic example, where superior German tactics, air-ground cooperation, good weather and sheer luck won the day.) In ancient warfare, certainly, morale and cohesion seems to have been the decisive factor. Battles were slugging matches until one side gave way, after which they were usually slaughtered. Incidentally, if you’re interested in such things, I’d recommend the site of Brett Deveraux, whose main interest is ancient history but has just done some excellent posts on tactics in WW1.

I’m with you and PK. I did a report for an undergrad anthro class 30 years ago about the spread of Indo-European languages and the use of horses during the Bronze Age – not much new here.

As far as this model being data driven, we are talking about social science “data” here and not physics. At the Bronze age excavation I worked on in the early 90s, we uncovered a wall that the director identified as a Bronze age construction, correctly in my opinion since there were other bronze age artifacts all around. Then we uncovered one solitary piece of glass near that wall, and suddenly it was a Byzantine era wall and not Bronze age at all. That’s a difference of 1500 – 2000 years, give or take a bit. If that’s the type of “data” being used in this computer model, I have to wonder how useful it really as, since as the author here admits, our knowledge of the past is very imprecise.

The site where I worked had visible above ground ruins which would attract people to come take a look even when the excavation was not active, and it being the summer in Greece and hot, they would routinely take a water bottle along. Some would litter and leave the plastic bottles at the site. It made me wonder if some curious Byzantine Greek had taken a similar look 1500 years ago and dropped their water bottle on the Bronze age wall, and whether some archaeologist in the year 4000 AD might excavate the area again, find a plastic bottle and date the site to circa 2000 AD.

Archaeology, as much as I do love it, is a very inexact practice. While modern archaeologists do use scientific tools, I’m still hesitant to call it a science since science involves making predictions that can be proven or disproven and by definition you really can’t make predictions about the past.

That reminds me of the story I heard many years ago of a series of excavations on Bronze Age ring barrows in the Curragh region of Ireland that turned out to be 19th Century gun emplacements used for artillery training. Archaeologists were initially fooled by some genuine Bronze age fragments found in the depressions that were probably just dug up by the military engineers when they were building them. Even top museums are littered with badly attributed items, one can only wonder at what sort of impact this has on big data analyses. And thats before you even get into fraud.

And then you get contemptible jokers who strew cheap ancient Roman coins off-trail in the High Sierra, with the full knowledge that they may never be found-or perhaps in 2222, causing some to think legionaries et al must’ve backpacked here once upon a time, and the obvious implication that they beat the Vikings & Columbus to the new world.

They probably didn’t need to bother with using real ones.

Turns out that the horse and Indo-European language spread are not connected:

https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/news/2021/09/genetics-shows-that-indo-european-did-not-arrive-in-europe-on-horseback

“The role of horses in historical warfare though has always been hugely exaggerated. ”

For some periods, maybe, but I’d say that horses had something to do with the rise of the Mongols, who conquered the largest empire up to their time and brought China and Europe into routine contact for the first time ever.

“Horsebound societies like the people of the Steppes usually only managed conquests when they worked out how to do boring things like siege warfare and building defence structures. ”

Siege warfare yes, defense structure no. But China without horses never extended its power very far west, whereas the Mongols after they had mastered both cavalry warfare and siege warfare pushed to Hungary, Germany, and Egypt and overwhelmed the Missle East.

“Horses provide tremendous mobility and speed on flat ground (which is why they were always used for flanking movements), but in up close warfare they are very vulnerable to any enemy with a blade on a stick who doesn’t lose his nerve on first contact (as its very well portrayed in Braveheart). ”

The compound bow (another tech innovation) allowed the Mongols to do most of their fighting from a distance. They also sent infantry cannon fodder into battle ahead of them while their prime troops stayed back until the kill.

Factors like these remade the states of most of Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia between 500 BC or so and 1300 AD. (But not south and southeast Asia, an Western Europe less than points east.

When you combine

This is quite right. Every advance in attack technology is countered by defensive tactics — and it usually is less expensive to defend than to attack.

In the Mithridatic wars, when chariots with scythed wheels slashed through Roman troops inn a big victory, the generals simply put up barriers and, as noted above, pointed sticks to overturn the chariots and kill horses.

The same is true today with super-weaponry defenses.

The Greek general Tacticus wrote (4th C. BC), If you want to conquer a town, promise to cancel the debts. If you want to defend a town, do the same to keep the army’s loyalty.

The authors neglect this dimension.

Sorry Michael, but my prior example of the Imjin War would render Tacticus mute. When Japan invaded Korea the samurai nobility cut the taxes and forgave all the debts of the peasants whose land they held on the peninsula. The reasoning being that a peasant wouldn’t care if they paid their now reduced taxes to a foreign lord as opposed to a domestic one.

Well, the Korean peasantry of Joseon cared and that’s when they began to wage irregular warfare against the Japanese invaders. Which is also the moment when Japanese atrocities began.

Is the japanese occupation of korea a case of local peasants not liking foreigners…because foreigners, or one of hot-headed occupation forces over-reacting to peasant resistance and inspiring more resistance?

As i understand, the japanese of the imjin era had no real prior experience with counter-insurgency and thought korea was a speed bump on the way to rolling over china.

I wonder if it was a little like Napoleon assuming the Spanish wanted rid of their corrupt clergy and aristocracy, and being more than a little shocked to find that the Spanish peasantry preferred ‘their’ rotten clergy to foreign atheists.

Ha! Your comment reminds me of an experience of my Irish mother’s taking a graduate course in history at an Alabama state university I will not name in the 1980s. The professor told the class that when some of the Spanish Armada landed on the coast of Ireland, the locals were so primitive and barbaric that they killed and cannibalized the Spaniards.

My mother, a proud Kerrywoman, pulled herself up to her full five-foot-ten, questioned the marital status and intelligence of the history professor’s antecedents in Gaelic and told him, before walking out, that when the Spaniards arrived, they were recognized as fellow Catholics and many intermarried with the locals giving birth to families of Mediterranean-looking “Black Irish” .

Many a battle has been lost because of misconceptions by one side or the other about the underlying loyalties of the locals.

You’re right about China being the real objective of the Japanese during the war. I assume Japanese rule in Korea was brutal and sparked the resistance. A samurai could lop your head off if you annoyed them. The tax policy / rice collection was just a good idea in the midst of near constant war. If the peasants all starve you won’t be collecting any taxes.

I’m not above speculating that the peasantry didn’t have an incentive to rebel against foreign rule. Participating in a war against an outside invader is a good way to advance your social position. It would entail rewards from the government and respect amongst ones peers. Although I have no idea why thousands of Buddhist monks joined the insurgency..

The moral of the story is that you should earn the love of people whom you invade/liberate. Buying it usually doesn’t work out in the long run.

Buying it in the short run could “buy”you time to earn it in the long run though, eh?

“If you want to conquer a town, promise to cancel the debts. If you want to defend a town, do the same to keep the army’s loyalty.”

Similarly, see Monty Python’s sketch “What have the Romans Ever Done For Us?“. For many ancients there were probably worse options and often significant material advantages to being assimilated into the Roman empire. I would assume this is true in many instances of large group formation bringing previously disparate groups together.

Hmm, it appears my comment didn’t post, so I’ll try again with an additional thought at the end.

“If you want to conquer a town, promise to cancel the debts. If you want to defend a town, do the same to keep the army’s loyalty.”

Similarly, see Monty Python’s sketch “What have the Romans Ever Done For Us?“. For many ancients there were probably worse options and often significant material advantages to being assimilated into the Roman empire. I would assume this is true in many instances of large group formation bringing previously disparate groups together.

The attractive power of materially beneficial technologies and cultural attainments, the “arts of peace” as it were, in formation of larger human groupings should not be overlooked.

Since a database is only as good as its schema, I took a quick look at the Seshat Codebook. No way to code for a mode of production, so far as I can tell, even by combining codes, which matters to some, I would think.

“It usually is less expensive to defend than to attack.”

This is an exaggeration. The steppe peoples NW of China had very few resources compared to China, but they were a constant threat for 2 millennia. The problem was that mobile attackers could concentrate their forces at any point along the defense line, but the defenders had to defend the whole line. China or major parts of Chine were ruled by nomads more than half the time between about 400 AD and about 1300 AD. And these nomad regimes often were supplanted by new nomad regimes: Khitan–> Jurchen –> Mongol in the north.

I think that’s over-stating the case a bit given a few historical examples. The Koreans mounted cannons onto their naval ships during the Imjin War which gave them a distinct advantage at sea. While the Japanese refined their usage of gunpowder weapons for their infantry.

Pick any random battle and you can probably guess the outcome based upon where it took place. At least until the semi-professional military of the Ming intervened in a decisive manner. Fortunately for the Koreans their navy severed the ability of the Japanese invaders to supply their forces.

I’m no expert on the Korean peninsula wars, but I’d always thought that the key advantage the Koreans had was that they were familiar with the very powerful and dangerous currents around the Korean island chains. The Japanese, used to the comparatively tame Inland Sea, were often easily outmanoeuvred by sailors with better local knowledge. In this way, it was maybe similar to how Drake out thought and out-fought the Spanish Armada.

The relative difference in seamanship definitely played a role in deciding the outcome. But my examples were about technology and it’s application during the war.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hansan_Island

The Koreans were lucky to have a great admiral in the form of Yi Sun-sin-

‘His most famous victory occurred at the Battle of Myeongnyang, where despite being outnumbered 333 (133 warships, at least 200 logistical support ships) to 13, he managed to disable or destroy 31 Japanese warships without losing a single ship of his own.’

And he died a Nelsonian death-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yi_Sun-sin

Late to the game, but I was absolutely gobsmacked by Yi Sun-Sin when I first learned about the guy. Incredible story, and though I can’t recall the name there was a relatively decent Korean movie about him. If I was a Hollywood Mogul, I would make a blockbuster about that guy.

His life, from beginning to end was….dramatic. Heres a Youtube series about the man that I kinda liked:

Part 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ieaDfD_h6s

Part 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKBOoPfMvLc

Part 3: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p97Xa6aB2jA

Part 4: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTan6eDphCk

Part 5: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=39Gsx6PaxiY

A Rev Kev hints (no further spoiler alerts, if you haven’t read the full wiki article…but yeah. His death is….indeed, so very Nelsonian. :)

Now that Korean TV series are getting quite popular in the States, there’s a chance Netflix might bankroll a series depicting this guy’s life.

We can hope! :)

The highest grossing and most watched Korean movie of all time according to Wikipedia :

The Admiral: Roaring Currents

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Admiral:_Roaring_Currents

It’s been available on Netflix for some time now. A little corny and OTT in parts but very watchable.

I think that the novelty is in identifying which factors impact the military tech evolution and which ones don’t.

I mean that it’s possible to write a plausibly sounding story why all of the latter matter and support it with a few examples. The point of Turchin’s methodology is to examine these hypotheses quantitatively

>>The biggest impact military tech has is when a society with one particular weapon happens to hit upon a society that has never seen that weapon before and doesn’t have the time to work out how to deal with it

This made me think of Greek Fire since I’m listening to the History of Byzantium podcast.

There were a ton of listener requests for an episode on Greek Fire.

The podcaster was unimpressed.

Greek Fire was only a show-stopper just after it was first deployed, repelling an attempted naval invasion during the Arab siege of Constantinople. The Arabs didn’t develop a counter-weapon, but they adjusted their naval tactics so it was never quite as useful again.

On the other hand, it probably helped scare off more naval invasions. No more sieges of Constantinople for 500 years.

amateurs study tactics, professionals study logistics and supply. underrated requisites,

The mounted Mongols under Genghis Khan and other such would appear to be an exception to this. Unless one wants to cite them as a case of a people with totally better military technology and methods who lucked into millions of square miles of people with no experience with Mongol materials and methods.

A lot of military history seems to ignore the Mongols. It’s true that n=1 so you can say that the Mongol empire is an anomaly, but it;s also a maximum, and Tamerlane, the Mughals, the Mamluks, and the Ottomans (and before the Mongols the Toba, Khitan,Tanguy, and Jurchen) were somewhat like Mongols.

Incidentally, a factor not mentioned so far (by me at least) is Mongol discipline. The Mongols were organized in a clear chain of command where each unit knew what its assignment was and after each battle there were adjustments, organizing the survivofs into new unitsif necessay and promoting those who ad performed well and demoting those who hadn’t.

The Mongols were also very attentive to strategy, scouting and intelligence, and they dispersed their armies and made feints so the enemy never could be sure where the attack would be.

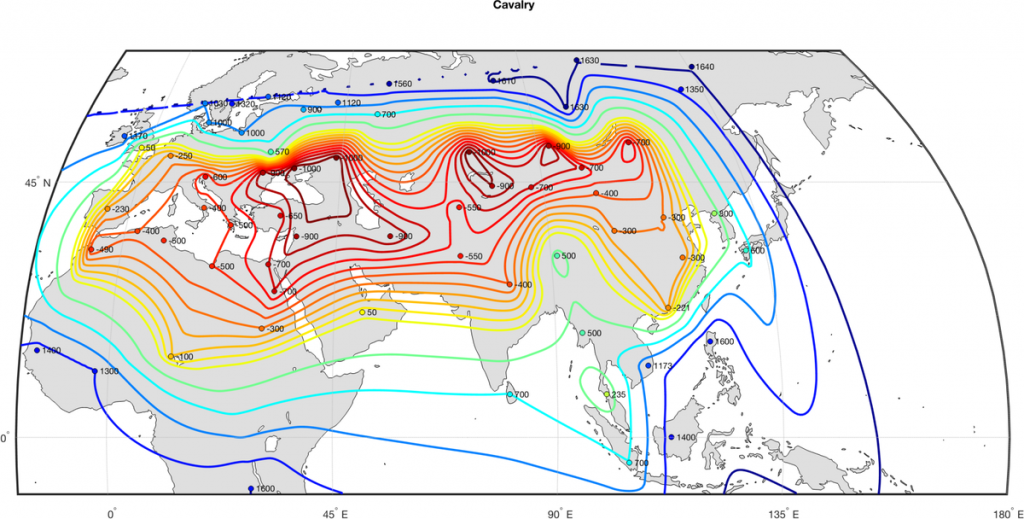

Yes, but the graphic is really cool! Imagine, they have a graphic like this one for each technological item.

Maybe they were inspired by the video game “Age of Empire II”‘s technology tree-

https://hszemi.de/2018/05/the-age-of-empires-ii-technology-trees-in-your-web-browser/

Cannot rule that out.

When I was in high school, my friends and I would get drunk pretty much every night of the week, and, because my friends’ parents owned a horse stable, we would often go out in the pasture and attempt to put tackle on the horses and take them out for a ride. We succeeded more often than you’d think, maybe 90% of the time. We enjoyed many a glorious moonlight ride.

What does this have to do with the article above? Well, it should make it clear that a bit and bridle allows a creature so low and so loathsome as a drunken human teenager to control a creature so noble as a horse with confidence. Not fair, but it’s a very good demonstration of the asymmetric nature of technology.

If you’ve the time for yet another hilarious Graves’ tragedy:

https://astrofella.wordpress.com/2019/05/08/count-belisarius-robert-graves/

It’s about BeliTsari’s adaptation of military technology, from the Huns, Mongols, Berbers, Celts, Teutonic tribes & Vandals

The three commenters above mostly covered the points that really matter but I will try for a few more. The study of military equipment can be a fascinating thing to study, especially the equipment of the average soldier through the ages. But it is not the most important thing defining military success. The American strategist John Boyd once said that it was a matter of people, ideas, technology – in that order. What I really think counts is training and doctrine. Norman Schwarzkopf of 1st Gulf War fame said that he could have swapped all their equipment with what the Iraqis used and the results would still have been the same. And I think that he had a point. And if you want to get brutal about it, the Taliban succeeded throwing Coalition forces out of Afghanistan using mostly AK-47s, RPGs, and their wits. The Coalition had the best weapons on the planet but in the end it made little difference. The right equipment helps but it is not a ‘silver bullet’ for success.

And this article talks about the appearance of military gear but there is nothing to say if they were being effectively used. As an example, tanks were first used in WW1 but it was only in WW2 that the Germans made effective use of them after spending twenty years of thinking how to use them best. The result for the Allies was devastating but a future archaeologist might discover remains of both WW1 and WW2 tanks and not know how they were really used. Another example would be this future archaeologist discovering British and German rifles from WW1 and find them comparable in performance. But he would not know that after the disaster of the 1899-1902 Boer War, the British spent a lot of time training their infantry in being marksmen. In the early WW1 battles, accurate British rifle fire decimated attacking German forces – but you would not know that from the archaeological record. And the same may be true of this database.

Well, technology like drones weren’t going to help the Coalition in Afghanistan even if the whole point of killing random civilians was a campaign of terror and psychological warfare.

I think it’s a bit early to assess the impact of drone technology on warfare. There’s still a lot of experimenting underway with the most recent example of Armenia vs. Azerbaijan being quite decisive on the side of the Azeris who bought a ton of stuff from Israel among others.

Ian Welsh thinks the cheapness of drone technology may turn out to be a kind of equalizer for smaller players.

George Orwell thought the sten gun (designed to be extremely cheap and easy to make) would be a force equaliser. It didn’t work out that way, although you could argue that the AK47 played that role.

I strongly suspect that drones will go the other way entirely. I don’t think it will be long before the major powers come up with effective means of either jamming or destroying the cruder drone swarms. The Russians have (allegedly) already worked out how to do it. The US Air force has just come up with a system to link clusters of cheap JDAMS in an anti-shipping role – a very cheap and effective way of completely neutralising China’s attempt to out-build the US navy. Its just part of the usual ebb and flow of technology.

It was Orwell who distinguished between “democratic” and “tyrannical” weapons. His argument is that it takes some time to be a competent cavalryman, and that such technology can never be used by the masses against the elites. Same applies to tanks and aircraft: the costs and complexity are such that they will always favour governments and elites generally over the people or revolutionaries. The Sten he thought (and Orwell had been a paramilitary policeman so he knew what he was talking about) was cheap to manufacture, easy to learn and easy to use, and so had the potential, if deployed in large enough numbers, to upset the balance of power against the Germans in France, or if they tried to invade the UK. In the end the Sten turned out to be not that reliable, but it would not have been possible to train and equip the Maquis forces that harassed the Germans in 1944 without it.

I knew a number of people who had been trained on the AK47, and they liked it for its characteristic of being what the British Army calls “soldier proof.” Modern (semi)-automatic weapons are much more complex and reportedly caused great problems for the Afghan Army.

There was the obscure Owen gun that may have been better to use. It was a tenth the price of a Tommy gun and was stamp pressed in production. The Australian military resisted it but the troops loved it for its reliability. My late father saw a demonstration of this gun once by its inventor, Evelyn Owen. He said Owen was at a beach and threw his gun into the water with all the sand and salt. He shook it under water and then pulled it out. A quick clean up later, he slapped a magazine in it and fired a burst of bullets up the length of a palm tree-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Owen_gun

I hadn’t heard this, but I kind of like Orwell’s way of thinking.

I think it helps explain the schizophrenia of the evolution of warfare with the use of gunpowder weapons.

Firearms for infantry were probably ‘democratic’, on balance since any random group of people with rifles can pose a threat to ruling powers.

However, cannons were probably more ‘tyrannical’ in the sense that they rendered ineffective a lot of defensive innovations in siege warfare over the previous 1000ish years.

Cannons also gave naval power a major boost. The Portuguese and Spanish launching a first draft, until the British Empire really mastered the idea.

The US added a new twist with air and sea power combined.

I’m no historian, but I am a former Army officer. A couple of thoughts:

The standard British rifle in both WW1 and WW2 was the Enfield. There are differences over time, but they’re essentially the same weapon.

The more interesting part of WW1 rifles is how long they were in 1914 vs 1917. The later models were much shorter. Longer rifles are more accurate, but much harder to transport in a truck.

Another interesting thing is that the French main tank in WW1 was the FT-17, and these were still in service, and somewhat effective, in 1940.

I wonder what future archeologists will think about Enfields and FT-17s.

“We found that the major drivers of technological innovation did not have to do with attributes of states themselves…“

This radical assertion flies in the face of what we know about technology today and state-formation in the past. Just about every component in a smart phone was made by various agencies of the US government decades ago. (eg; DARPA, DoE, etc.) They are the product of state investment in military-backed technologies that eventually transition into the civilian sphere.

The proliferation of technology that was facilitated by trade began as a state-backed initiative in the historical era they’re researching. The Silk Road had it’s origins in an effort by the Han Chinese to colonize it’s western borderlands. These military colonies were meant to serve as logistical supply depots to furnish their military with provisions so they could project power further into the Steppe. It was only later that merchants and trade caravans received permission to use the infrastructure that the Han government built. This example would seem to disprove their demographic-orientated analysis.

There are other factors which influence the invention and refinement of technology. The development of the bit and bridle and stirrups was probably the result of the harsh environment of Central Asia. Where the productivity of livestock was a matter of life and death. I just don’t think that statistical analysis or demographics can explain everything that happens in the study of history.

That’s very interesting, do you have any sources for the smartphone’s history, because all the books I found go from a calculator through computers and finish with laptops. Now there is bunch of people resisting google controlled operating systems for smartphones but that’s another story -software not hardware.

Deveraux’s defense of the Classics a must read for history buffs, as well as everyone horrified by Washington’s daily emulation of the collapse of Imperial Rome.

Took Latin in high school to avoid language lab and because years of reading National Geographic left me fascinated with ancient Greece and Rome. Son just returned from a vacation in Italy – testing, vaccination and masking all taken extremely seriously there – so great to hear his impressions of Rome and many photos of same.

If you enjoy time traveling back to ancient Rome, this author is highly recommended. (Helps if you like reading murder mysteries…)

https://www.lindseydavis.co.uk/

I see a few people asking what’s new about this approach. While the idea of military technology being a driver of state formation is not new, attempting to use big data to correlate it with the formation of large states and empires is new. If you’re familiar with Turchin’s work, you know that using data to take a quantitative (as opposed to merely qualitative) approach to history and testing different theories by using this approach is a major part of his work.

The thrust has been understanding how societies became larger and more cooperative over history. More cooperative societies are more effective at warfare than less cooperative ones. In his theory, it is the existential pressure from military competition that forces states to become more cooperative or perish and be assimilated. Societies that cannot scale up organizationally are weeded out by those which can. So superior weapons lead to pressure on societies within the arena to develop better social organization, discipline and tactics or face extermination. That’s the key takeaway rather than just “societies with better weapons win.” I would argue that haute finance can be considered to be one of these “technologies”.

As for debt forgiveness, that fits squarely into the picture. Turchin would probably concur (hate to speak for him, but oh well), that societies where the majority falls into debt slavery is a society that will fall to it’s competitors, therefore forgiveness of debts becomes a cultural imperative. He describes the philosophies of the Axial Age as a response to increasing pressure on agricultural states from steppe empires. Those philosophies boil down to “forgive the debts and redistribute the land.” Prof. Hudson’s work is quite complimentary to Turchin’s.

I’ve written reviews of Turchin’s latest book Ultrasociety which can explain some of these ideas better:

https://hipcrime.substack.com/p/ultrasociety-by-peter-turchin-review-cfe

So, modern neoliberal societies, infested by catabolic capitalism, growing ever less cooperative, are less and less capable of large scale operations like the war mobilisations of the world wars.

Or climate change mitigation.

Or actual pandemic responses.

Bingo. We. Are. Less. Capable.

This is a great term: “catabolic capitalism”. An economic situation that consumes/digests rather than produces, Only at NC do you read metabolic references to economics.

Also, parasitism. I have long found biological analogies more useful for political economy than those from physics.

I remember having seen/read Richard Heinberg use the term “catabolic capitalism”.

And there is a website titled “catabolic capitalism” devoted to the concept that present day “capitalist” civilization is consuming its own “flesh” on the way downward to collapse.

https://www.catabolic-capitalism.com/resources.html

While it’s not popular to admit, one of the most reliably effective technologies for social cohesion at scale has been religion.

I’ll do some pushback here as i’m seeing a lot of commenters saying, ‘nothing new here’.

In my view, that sort of misses the point. Firstly, it’s good to assemble bits and pieces from various sources into a kind of synthesis that can give a real crash course to newcomers to this history.

Secondly, it seems the 10k foot view of tracking where/when those innovations arrive at various locations can also provide a new lens with which to understand history.

I enjoyed the post and sources cited, and of course the comments, too! As lambert says, NC is the best.

Well, I found the article to be an interesting use of computer technology (relational database) and an attempt to fit historical facts/events into it. But I’m not sure any of its output has validity. I see it as an opportunity to “run some scenarios” , see what develops, then debate whether it was accurate/useful.

You’re absolutely right about the Commentariat. Who knew there were so many hidden tactical observers/readers of the practice/motivation for warfare!

“Nothing new here” misses the point. This is about social structures required to evolve based on existential threats posed by military technology. The social change required to use a new weapon is a critical takeaway of the presented work (e.g. English longbow made combat skill at lower social level decisive).

In the present day, does anyone think that militarized AI tech in the hands of a single aggressive military society could not inflict their will upon other societies that are without AI technology? There are such things as step change technologies that change the battlefield completely. Peer competitors are defined mainly by their military technology. When that balance is changed, they are no longer peer competitors.

To argue that there are going to be countermeasures eventually misses the point that “eventually” could be after the destruction of your society.

A small percentage of GI Joe’s in battle in WW2 actually fired their weapons, becoming ad hoc conscientious objectors in the bargain.

Militarized AI won’t have any issues with that~

Unfortunately, militarized AI might not have an off switch as well, which might become an issue, rather like the landmines and water mines that are still lethal and killing people, some more than a century after their placement. IIRC, the oldest mine to kill was a Confederate torpedo (naval mine) that kill an amateur historian about a century and change after the Civil War. Just think of all the bombs and shells from the world wars as well, which are also still killing the occasional unfortunate as well as making large areas of land unfarmable, if not uninhabitable. France, Cambodia, Vietnam, and countries in Africa all have areas like that.

Also, on paper, the Taliban should have lost the war and, supposedly, the AI revolution I have reading about for decades is supposed to change everything, but while the battle and war tends to be won by the bigger battalions and those with most murderous (murderous) weapons, it often just means that more people die.

I think that there will be some incident in which we will see why computers that can keep making a mistake a thousand times faster than an individual will be a problem.

Militarized AI might decide it does not like people and would like to delete us. And it might be intelligent enough to decide that “military methods” are too slow and not thorough enough. The AI might take over germ-labs and make and release bio-weapons all on its own. It might also figure out how to manipulate human society leaderships into accelerating the fossil carbon burn in order to achieve a high enough skycarbon level that all the people will die . . . if that is what the self-propelled AI decides it wants to do.

Wouldn’t it be ironic if China’s lead in AI translated into China’s AI being the first one to break free and begin its own Operation Delete People and started with the people in China?

Yes, that’s what saw Ramez Naam in Nexus Trilogy. (It made a cool Covid shutdown reading) but with much more politics involved.

I know this is just an exposition of the project but it is a shame they didn’t mention the stirrups. They made the use of other weapons feasible. If I remember well from my art history, Romans didn’t know about stirrups. So they could not vield arms freely while riding at the same time. This article says they were first found on an archaeological site India : https://americanequus.com/history-of-stirrups/ in Europe they came much much later.

This entire discussion is very pre-1945. There is no defense against nuclear weapons. After decades of effort and tens of billions spent. The US has a “success” rate of about 50% in intercepting incoming test missile targets (without countermeasures or evasive maneuvering capabilities). If war is the drug, nuclear war is the lethal overdose.

The “nuclear bombs changes everything” has been used in arguments since they were first exploded 76 years ago. It was the same with machine guns and the aerial bomber. Yet, while the bomb has the ability to end civilization, there have been many awful wars since its creation.

I’ve no idea how effective it is and the Russians don’t reveal much but they may already have a working ABM system in place to protect Moscow. One that has been recently updated.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A-235_anti-ballistic_missile_system

It’s entirely possible they’re also working on a system to extend this cover to a few other important cities and regions.