This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 1561 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, more original reporting.

And if I may add a personal note, from just looking at the top of the front page: Where else in the world do you find a site that covers COP26, war, imperialism, the labor market, OSHA and its vaccine mandate, and regenerative agriculture, all in one news cycle? Along with two heaping servings of linky goodness every weekday? I say nowhere.

So, if you have not contributed, please do so. No donation is too small (cf. Luke 21:1-4). Now, some readers may not be in a position to donate, and that is fine; we don’t want anybody to go hungry or skip the bills, after all. However, if you have already donated, and you are in a position to do so once more, won’t you please consider donating on behalf of small donors who cannot? Thank you!

By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

For some time, readers have been chivvying me to review Gabe Brown’s 2018 book Dirt to Soil (Chelsea Green; list $19.95[1]). Well, “chivvying” is not quite fair; rather, readers have been not-at-all ostentatiously dropping his name in comments, rather in the manner of parents leaving copies of a book they want their recalcitrant teen-ager to read beside the couch or out on the kitchen table. Well, it turns out that readers OregonCharles, pileusII, drumlin woodchuckles, HotFlash, and Mike G got ahold of the right end of the stick; Gabe Brown’s book is definitely well worth a read (and very hopeful, a good thing these days).

This will not be an exhaustive review of Brown’s book, or a treatise on regenerative agriculture. Rather, I will, as is my practice, pick out a number of bright shiny objects that I think Naked Capitalism readers can make use of. Since I don’t have an electronic copy of the book, and don’t have time to type in long passages from the book, we are mutually reduced to bendy screenshots of pages from the book, which I have helpfully highlighted. I will look at Brown as a media figure, the Five Principles of Soil Health, the depth of Brown’s topsoil, what Brown called “the production model” of non-regenerative agriculture (“Big Ag”), and finally at Brown’s carbon-based “Income Statement.”

(1) Brown as a Media Figure.

Brown is, it is clear, a media figure. He is out there pushing for — in an unguarded moment, he might say “evangelizing” — his ideas, and very effectively, too. In this, Brown resembles Joel Salatin of Polyface Farm (who I learned about from Michael Pollan (whose Omnivore’s Dilemma Brown references (p. 183))). This is a good thing; but it’s also a thing[2].

(2) Rules for Soil Health. Please forgive the way these pages are cobbled together:

I’m glad Brown put the Rules right up front, instead of taking a hundred pages to build up to them. I have helpfully underlined words like “look out,” “take a walk,” “you will still see,” because as Yogi Berra says: “You can observe a lot by just watching.” No matter whether our plot or land be large or tiny, we can all exercise our senses and draw conclusions from them. For example, from Rule 2: “Keep covered at all times.” Why? When you look, you see that “bare soil is an anomaly.” And even in my very, very limited experience as a gardener, I know what when I sheetmulched my patch — sheet-mulching is the gateway drug to permaculture, as perhaps permaculture is the gateway to regenerative agriculture — the soil got darker, fluffier, and just more generally pleasant to the hand, and very different from the horrid riverbank clay I started out with. There is also a good deal of pure pleasure to be had from Rule 5: Pollinators, predator insects, earthworms. Pollinator insects are relaxing to listen to, and pollinator birds are fun to watch (like those hyper-aggressive little fighter jets, hummingbirds). And before I sheet-mulched, no earthworms. After I’d been sheet mulching two or three years, many of them. It’s a good feeling to discover that the soil is alive when situating a plant within it. I realize these are my relatively trivial experiences as a gardener, rather than a farmer, let alone a farmer running a very profitable enteprise; but the sheer pleasure Brown takes in all those goes into making dirt soil shines through on every page. I highly recommend the feeling.

(3) The Depth of Brown’s Topsoil

Taking Iowa as an example, Iowa has lost a lot of topsoil:

According to the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Iowa has lost an average of 6.8 inches of topsoil since 1850. The Iowa loss of topsoil is unsustainable at the current rate. The best scientific estimates put the average rate of rebuilding top soil at ½ ton per acre. That indicates Iowa is losing topsoil (5 tons per acre) at a rate 10 times the rate of replenishment (.5 ton per acre). Iowa’s rate of loss of its black gold suggests farmers must reverse this trend or future generations of farmers face a grim outlook.

Conventional wisdom says that it takes generations to build back (oops) topsoil once it’s been lost[3]. From the USDA:

An often asked question is, “How long does it take to form an inch of topsoil?” This question has many different answers but most soil scientists agree that it takes at least 100 years and it varies depending on climate, vegetation, and other factors.

(LandStream is a consulting firm, hired by Brown in 2018 to assess his soil. I cannot find the results online[4].) If Brown’s figures are correct (I do note that qualification, “some samples”) then the USDA is wrong (not unheard of for Federal agencies ***cough*** CDC ***cough***). If if topsoil can be regenerated in years, not decades, that opens the way for my hair-brained scheme to restore the Great Plains to its former glory (and pay its inhabitants for doing that[5]).

(4) The Dominant “Production Model”

Crop insurance-driven business decisions don’t seem like profit calculations at all, to me. They seem a lot more like rents (and very much dependent on luck, too, as last year’s flooding shows. And as climate changes, more and more unluck may end up destabilizing the crop insurance system, as it looks to be destabilizing flood insurance). Big Ag looks a lot like Big Pharma, to me. I wonder what Stoller would have to say about all this…

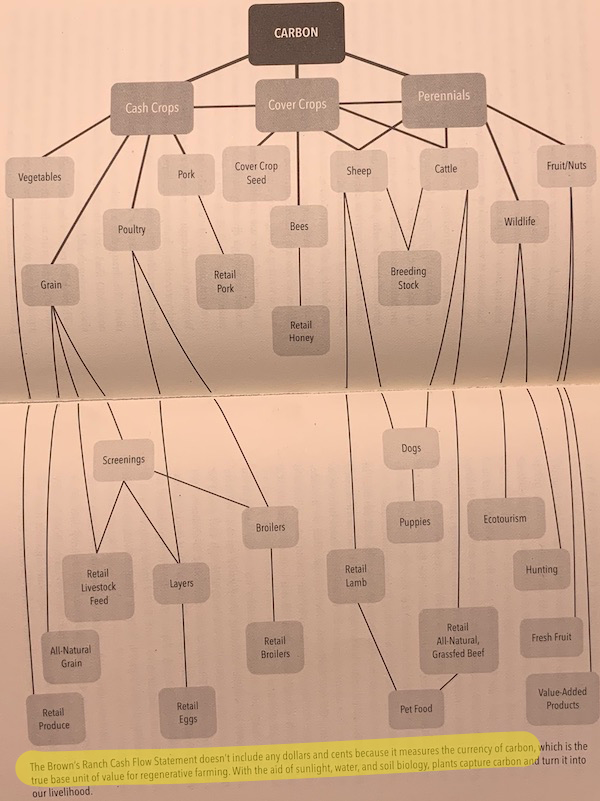

(5) Brown’s Carbon-Based Income Statement

At one level, this is a fascinating approach to agriculture. Starting at the root, Carbon, Brown creates three categories: Cash Crops, Cover Crops, and Perennials. Within each category, he labels a carbon flow, which is simultaneously an opportunity for profit (and not at all a “luck of the draw” rental extraction, as in the dominant “production model”). For example, planting cover crops induces a flow of bees, which induce a flow of honey, which is sold at retail. Grain when processed creates a flow of screenings which feed a flow of chickens, also sold at retail. (Awkwardly for what looks like a tree structure, there are cross linkages between items under separate categories; for example, cover crops and perennials both feed sheep and cattle, which are both sold for breeding stock and at retail. When I see a tree structure trying to become a graph, my impulse is to think that matters are more complex than they first appear, and when I start tugging on loose ends, I’ll find out some interesting things. However, that is neither here nor there for the purposes of this review.) Brown describes how his approach makes for a good family business. Page 195 et seq.:

Because Shelly and Paul and I [Brown’s family] have set up this rich diversity of income streams, our ranch is resilient not only ecologically, but financially, too.

When I travel around North America to give presentations about our farming methods, I hear over and over again that there is no money to be made in production agriculture [“Big Ag”]. My story, however, is proof that there is good money to be made when you think outside the box.

Even though we already run seventeen enterprises on our operation, we have many more that we would like to add in the future….

At almost every presentation I give, someone asks: “How many employees do you have in order to get all that work done?” The answer is: “Shelly, me, Paul, and Paul’s girlfriend, Shalini Karra. For five or six months each year, we bring on a couple of interns

… Rather than talllying up how many enterprises we run and thinking of it as a burdensome workload, I tell people to think about all the tasks we don’t need to do….. For example, we don’t need to haul and apply fertilizer, pesticides, and fungicides. We don’t need to vaccinate and worm our livestock…. We don’t have daily chores of starting up farm equipment to haul feed to the livestock during the winter. We don’t have to spend time hauling manure from the corral out to spread on the fields.

And:

Stacking enterprises gives greater opportunity for profitability.

Seems like a generalization of permaculture’s “stacking functions.”

A few observations on Brown’s “Income Statement” and his larger project of agricultural regeneration:

(A) We are not looking at an income statement, even in terms of carbon. There’s no bottom line labeled “NET.” What we have is a map of potential enterprises based on stocks and flows of carbon. That is an excellent thing to have, but it’s not an income statement.

(B) Conceptualizing such a map as an income statement strikes me as uncomfortably close to the “ecosystem services” model, with each enterprise modeled as an ecosystem service. As readers know, I don’t accept that ecosystem services can be priced, and that includes the services — if services they be — provided by soil, and so it concerns me that Landstream Services (the consultant hired by Brown to assess his soil, whose deliverable I cannot find) is involved in such efforts in Vermont.

(C) Let’s ask ourselves what Brown’s relation to the means of production is. In class terms — and by this I mean no disrespect, in fact quite the reverse — Brown is a peasant. Here is the definition of peasant from my Oxford English Dictionary app:

peasant

/ˈpɛz(ə)nt/

noun & adjective. LME.[ORIGIN: Anglo-Norman paisant, Old French païsant, païsent (also mod.) paysan alt. (with -ant) of earlier païsenc, from païs (mod. pays) country from Proto-Romance alt. of Latin pagus country district: see -ant2.]

A. noun. 1. Chiefly hist. & Sociology. A person who lives in the country and works on the land, esp. as a smallholder or a labourer; spec. a member of an agricultural class dependent on subsistence farming. LME.

(Obviously different in kind from a Big Ag farmer producing a monocrop for export or to be turned into High Fructose Corn Syrup.)

And see also:

■ peasantism noun (a) the political doctrine that power should be vested in the peasant class; (b) the political doctrine that the peasant class and the intelligentsia are the only true revolutionary forces: l19.

■ peasantist noun & adjective (a) noun an adherent of peasantism; (b) adjective of or pertaining to peasantists or peasantism: l19.

■ peasantry noun (a) peasants collectively; (b) the condition of being a peasant; the legal position or rank of a peasant; (c) the conduct or quality of a peasant, rusticity.

Again, I mean no disrespect; a peasantry (“Chiefly hist. & Sociology” my Sweet Aunt Fanny) that can become stewards of the soil as Brown shows that his family can (see the Appendix) is not to be sneered at, but to be encouraged. (“In the Confucian view of the economy, agricultural work was morally superior.”)

However, scaling Brown’s “Carbon Based Balance Sheet” approach even to the level of multiple counties, let alone to States or regions, necessarily requires the creation of a peasant class. That again may be no bad thing; if, in some alternate universe, The Bearded One had read From Dirt to Soil, he would not have made his infamous remark about “the idiocy of rural life,”[6] since Brown is plainly not an idiot.

That said, for a class of small-holders to be created on, say, the Great Plains, there are a lot of structural issues to be addressed, beyond propagating the regenerative skills and enterprising attitude that Brown exemplifies. Probably something on the order of land reform would need to be implemented — it’s hard to imagine regenerative agriculture being performed by sharecroppers — and debt would need to be addressed, so peasants wouldn’t be reduced to the status of serfs.

Needless to say, our current political economy isn’t big on debt relief or protection, let alone prying farmland from the sucking mandibles of private equity.

Finally, and there’s no denying it, being a peasant is hard work and involves risk. Not every peasant will be going on speaking tours! If we regard regenerating America’s soil as a public good and a national project worth undertaking, then moving from dirt to soil will not be enough; we will need to move to a support structure for an emergent peasant class as well.

NOTES

[1] If you alllow pop-ups, you’ll see an offer to sign up for Chelsea Green’s mailing list, in which case you get a discount on your next purchase.

[2] The finance-adjacent person in me wonders where the appearance fees, if any, fit into the Carbon-Based Income Statement discussed in section (5).

[3] The scope of the work is indicated by the title: “One Family’s Journey into Regenerative Agriculture.” “Desertification” does not appear in the index; it is not clear to me that Brown’s techniques apply when desertification has reached a stable state. It would be nice if it did; see Greening the Desert at NC (2012).

[4] LandStream does exist, but is quite small. I was amazed to find the name of LandStream’s owner, Abe Collins, in a usage example for “regenerative” in an online Somali-English dictionary. That speaks well of him, I think.)

[5] Big Ag likes to think of itself as “feeding the world,” and, I think, takes its inspiration from Norman Borlaug. It’s not clear that’s a Jackpot-compliant model, and may even be bringing the Jackpot closer. Now, cloning Gabe Brown and sending a clone army of Gabe Browns to India, Africa, and China, on the other hand…. That would feed the world.

[6] But see here for a retranslation/defense.

APPENDIX

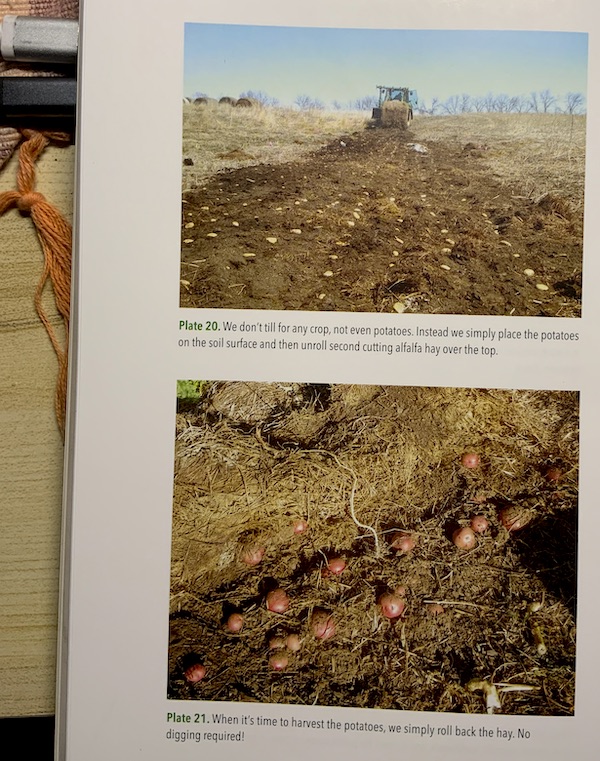

Dirt to Soil also includes 26 illuminating color plates, often with extremely polemic captions. Here is how Brown’s Ranch grows potatoes:

Digging potatoes seems like work, so Brown’s seems like the better system. I wonder if anybody in Aroostook County has tried this technique?

I “discovered” regenerative agriculture several years ago, also via a Chelsea Green book, and the more I study it, the more convinced I am it’s desperately needed. Unfortunately, in addition to Big Ag, we also have to contend with slew of city-dwellers who lump everything agricultural into one amorphous lump and declare it evil. They will argue till their dying day that the only real problem is “eating meat”, and that we should just all go vegan and that will solve everything.

I’ll note there are more than a few excellent videos on YouTube on the subject, and Apple TV+ carries the documentary The Man Who Stopped the Desert, which is both an inspiring story of how regenerative agriculture (in this case using indigenous methods) can initiate tremendous changes, and how free-market greed far too often rears its ugly head and destroys all progress.

I grew up on a small farm in northeastern PA 70 years ago, and know first-hand how easily being able to make a living at it gets undermined by all the “agricultural extension service” advice that relies on expensive fertilizers and hybrid seed sales. We don’t need monoculture and factory farms to feed us, because in point of fact both of those create more waste than anything else. Of all kinds.

All we need is a politically-motivated customer-base who are ready to pay for old-style food from old-style farms. The more such customers there are, the more such farms can be supported.

And any potential customer who also has a real house with a real yard around it can perhaps grow some of herm’s own food in herm’s own yard, so as to save some money for buying higher-priced shinola food with.

Too much gov. or captured gov.

Thank you, Lambert. I’ll get this book to inform my aspirational backyard ‘peasantry’.

At first glance, I’m not thrilled with the potato method. The output per square meter seems quite low compared with what I think I have read can be achieved if one hills soil or mulch as the plants grow, so that the potatoes are produced in a 3D volume rather than on a 2D surface.

I wonder what they do to retard potato beetle damage.

My thought too. New potatoes only develop above the seed potato, which is why potatoes are hilled with soil and/or mulch.

If you have hundreds of square meters to work with, low output per square meter may be enough output overall. If you have only 2 or 3 square meters to work with, you will want to make the stem-surrounding hilling of the potatoes as vertically tall as you feasibly can for the most potatoes per hill given the rigid restraint on the possible number of hills.

Someone should ask Mr. Brown how he retards potato beetle damage the next time he gives a public talk or appearance at a conference. I imagine he would be happy to say what he does.

Here’s what I might do with the five or six potato hills I could fit into my very small garden if I were to try potatoes at all. With that few potatoes, I could afford the time to kill each potato beetle by hand. The fastest easiest way might be to use a squeeze bottle with a long narrow snout and filled with vegetable oil, and put a few drops of oil on each potato beetle to smother it to death under the layer of air-excluding oil.

I would focus on the tiniest potato beetle larvae first because they have the most growing yet to do and will do the most damage to achieve it. I would work my way up to mature egg-laying-size adults and kill them all too to prevent them laying eggs. I would hunt for every possible little egg mass already layed but not yet hatched, and put some drops of oil on each of them.

Here are some images of potato beetle egg masses. I think they are hidden on the undersides of the leaves so it would take some work to turn each leaf upside down to find the egg masses. On the other hand, the egg masses can’t run away and hide.

https://images.search.yahoo.com/search/images;_ylt=AwrJ61ohw5xhqRsAochXNyoA;_ylu=Y29sbwNiZjEEcG9zAzEEdnRpZAMEc2VjA3Nj?p=colorado+potato+beetle+egg+mass+image&fr=sfp

Thanks for this. The word “dirt” implies an inert and a singular physical structure, like Lead (Pb) or Iron (Fe). The word “soil” implies an alive and complex and multifaceted environment for growing plants (and their associated insects and animals). “Dirt” is what one wipes up on a dust cloth when cleaning the house or wiping off the car windshield; soil is life-cycle renewing results though natural seasons of growth/decay or cropping or forestry. This sounds a bit, um… romantic, I know.

adding: see the many utube videos about turning sand into soil, etc.

from Wikipedia:

Gabe Brown (left) and Ray Archuleta are prominently featured in “Kiss the Ground,” a feature-length movie which focuses on regenerative agriculture as a solution to ecosystem, health and climate problems.

i recommended this doumentary before when the subject of regenerative agriculture was topical.

here is the link again

https://kissthegroundmovie.com/kiss-the-ground-netflix-movie-features-soil-health-pioneers-ray-archuleta-gabe-brown/

just sayin…

With regard to the peasantry as a class, I am reminded of Thomas Jefferson’s comment to his nephew Peter Carr,

I really liked Lambert’s tangent into how important a peasantry can be. You could probably argue agriculture overwhelmingly for market sale (even among otherwise small farmers) was another one of America’s original sins. It ties into so many others: slavery, ecological degradation, lack of solidarity, land grabs. I remember watching a TV show (an episode of Nova?) that mentioned even Washington & Jefferson were already freaking out about soil exhaustion on coastal tobacco land.

And of course, it’s hard to keep the Satanic mills running if the workers can just say “take this job & shove it; I’m moving back to the Shire & growing squash.” I think Kropotkin even wrote at one point that he thought the Paris Commune could have succeeded if they hadn’t alienated the countryside.

As for the gardening itself, I would love to do this sort of thing & make permaculture one of my main hobbies. Unfortunately, I don’t have my own place or land right now, so I’m still surrounded by chemically-treated, grass lawns (barbarism!) But mark my words, once I do have my own place, I will bury my lawn under a righteous wave of compost and mystery-bag seeds from the nearest native gardening club.

> I really liked Lambert’s tangent

Tangent? Moi?

As for gardening, if you have a window or a porch, you can start out small with some pots :-) DCBlogger grows herbs and vegetables that way (though not much, of course). Start from seed, of course….

What is “Marxism” spelled backwards? “Hegelianism”? “Msixram”? What if a tiny new class with a motivating ideology figures out how to recruit parts of the wider society into helping that new class get big and numerous in order to make its ideology powerful enough to influence society and politics in favor of further growing that new emerging class to a safe and stable size?

Years ago in Acres USA, Charles Walters used to write about the possible emergence of a new class of small-scale farmers in growing numbers, eventually getting large and then huge enough to assist in tearing down and destroying the huge petrochemical cancer-juice mainstream farms of today. And we are seeing the emergence of growing numbers of owner-operated lived-on small farms selling to motivated suburban and urban customers. And hiring as little non-family labor as possible. A new market-peasant class or a “yeoman farmer” class if one wants to be romantic about it. With an ideology of ecosystem and environmental repair and upgrade, sometimes expressed as “regenerative agriculture”.

Enough development in that direction and we might see Earl Butz’s imperative stood on its head, at least within 50 or 100 miles of medium and large urban centers full of picky-choosy customers.

” Get small or get out”.

And further away from such centers, we will at least see a new imperative of ” get clean or get out”. Charles Walters invented for his paper the Masthead Motto . . . ” To be economical, agriculture has to be ecological.”

I was reading Gabe Browns Book yesterday. He definitely does not operate on the scale of a subsistence peasant but that of agri-business. His operation at the time of the publishing of the book was 5000 acres, part owned part rented. His cattle herd is 300 head + each years calves. He repeats several times in the book that the book is aimed at production farmers like himself, saying if he can do it so can they.

Saying that, nearly all of what he does can be done on the peasant scale with a bit of imagination and thinking through the application. I have 4 1/2 acres in the UK, half coppice woodland (heat fuel, garden poles & fence posts) half vegetable allotment, soft fruit, orchard and nut platt. Of the products only the nuts are sold commercially, the rest I use for subsistence i.e. my scale is peasant scale (plus a small cash job, not an unusual mix historically for peasants). Gabe’s five rules are solid gold though.

Agribusiness scale farming will continue while diesel fuel lasts. Once that is gone farms will have to re-scale to using horses again, many will be at peasant scale, but if towns and cities persist many will be larger selling commercially to the urban areas.

Gabe’s potato production is low per unit area, but he has the space, mulch, and heavy equipment to apply large amounts of mulch, plus he does not want to break the soil. His system suits him.

My system, I grow a lot of pole beans in double rows tied together at the top. This leaves dead ground below into which I plant a row of main crop potatoes as deep as I can followed by a ridge of compost on top (please note the potatoes and compost go in before the pole beans). The potatoes and beans do well. I just have to check a couple of times in the season if the potatoes need earthing up which I do with a hoe, usually not much required. My system suits me.

Gabe says several times in the book that it is not gross production that is important but whether you can make a profit from it. Now I measure my profit in a different way to Gabe, but it is still basically the same: maximum output for minimum input in both cash and labour. The skill is in maximising the output for the inputs you are willing or able to expend. Gabe’s book gives a lot of knowledge to improve those skills and through those your soils and crops!. I could not recommend it more highly.

Best wishes to all Philip

> I was reading Gabe Browns Book yesterday. He definitely does not operate on the scale of a subsistence peasant but that of agri-business. His operation at the time of the publishing of the book was 5000 acres, part owned part rented. His cattle herd is 300 head + each years calves. He repeats several times in the book that the book is aimed at production farmers like himself, saying if he can do it so can they.

To begin with, it’s not a question of scale but of social relations. That said, at scale, social relations can change. If Brown outcompetes all this neighbors — remember, they aren’t running a media operation, etc. — and they lose their land and become Brown’s hired hands…. Well, now we’re back to capitalism, and all the incentives that ruined to soil in the first place.

Prediction is hazardous, but I will make one anyway. Brown won’t try outcompeting his neighbors to drive them out of business and acquire their land. He will keep his operation “small” enough that he and family members can work it themselves without hiring bunches of people, or even very many, to work it for the Brown family.

If his neighbors approach going out of business slowly enough that they can swallow their pride and ask him for his advice before it is too late for them, he will probably give them his advice.

If his neighbors go all the way bankrupt and have to sell their land, the only reason he would buy any of it would be to establish a defensive perimeter of neo-virginoid prairie around his place to keep the pollutionists farther away. And if various state or municipal governments were to acquire that land for the very same purpose of prairie restoration, he would be equally happy about that as long as it establishes the same eco-defense perimeter and buffer between himself and the mainstream pollutionists. Perhaps he will become a lone eco-peasant in a spreading sea of buffalo and prairie.

Since his neighbors are probably too attached to the petrochemical GMO Haber-Bosch death cult to ever change, the coming Haber-Bosch unaffordability shortage combined with the sort of wild weather swings which chemo-autoclaved dirt will be unable to cope with will drive his neighbors bankrupt and into liquidation faster than they can believe. The only thing which could get him to buy that land would be a misplaced desire to help rescue and restore it. “Misplaced” because that much more land would be beyond any one family’s ability to handle, in my ignorant layman’s opinion.

So that’s my prediction. If his neighbors all decide to commit farm-suicide to show their devotion to the mainstream model, he will watch their operations die with all due sadness to be sure, but without any desire to board the Titanic in order to fix the leaks. And some of his neighbors will do it fast enough that I will live long enough to see my prediction turn out right or wrong.

I am a hobby gardener with a very small garden. A garden is not just a tiny farm and a farm is not just a huge garden.

If I wanted to grow a few potatoes, I would have to go somewhat vertical and pile mixed soil and mulch fairly high up the growing potato stems, chasing their upward growth upward. I would have to try growing as much potatoes as feasible per each of rather few potato planting spots. Brown can spread way out laterally.

After the Cromwellian invasion of Ireland, the Irish were driven into the least fertile and flat parts of the island, from what I have read. They had to develop a method of growing potatoes which would work with absolutely minimal cash input, since they were left with minimal cash if any at all. So they developed a method called “lazy bed” potato growing. It reminds me of Brown’s putting potatoes on the soil surface and then laying mulch over them.

Here is a blog entry about ” lazy bed” potato growing.

https://www.betterhensandgardens.com/growing-lazy-bed-potatoes-a-complete-guide/

Here is a very condensed version of the same thing by the same author.

https://www.hobbyfarms.com/grow-potatoes-in-lazy-beds/

Here is a different blogpost about lazy bed potato growing from a blogger-gardener in Ireland itself.

https://connemaracroft.blogspot.com/2011/04/potato-planting-lazy-beds.html

Thanks for posting about Gabe Brown. He is truly an inspiration and makes you want to be a farmer. For those who don’t have the book and want to learn more about this subject I recommend the following videos:

Treating the farm as an ecosystems part 1 https://youtu.be/uUmIdq0D6-A

Treating the farm as an ecosystem part 3 https://youtu.be/QwoGCDdCzeU

In the latter video, Gabe goes into the business side of their enterprises. By limiting inputs and selling directly to consumers, Gabe is able to have a successful and profitable business. One thing that he mentions is that he doesn’t sleep very much. Maybe 4 or 5 hours a night. I doubt many people could replicate his workload.

Regenerative agriculture is greatly needed all across the world. We must move away from utilizing fossil fuel derived fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and insecticides. Hopefully Gabe can make some in roads at land grant agriculture colleges.

> Hopefully Gabe can make some in roads at land grant agriculture colleges.

That would be excellent. It’s what they’re for, or should be.

one example of land grant u’s and brown. what you are asking for is happening! https://csanr.wsu.edu/regen-ag-solid-principles-extraordinary-claims/#comment-121465

This could be another example . . .

Recently I heard on BBC a program about a present-day advance towards partially regenerative agriculture for extremely small-scale peasant farmers in Zimbabwe. Since I am at a “no sound” computer at the public library, I can only hope this link I will provide is a link to that broadcast.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/w3ct2z2z

The method is called Fumfudza. It appears to use some of Gabe Brown’s concepts, whether taken from Gabe Brown or from previous developers/inventors or developed in parallel right there in Zimbabwe. Here is a link to an article about it.

https://allafrica.com/stories/202006120509.html

And here is a link to ” Fumfudza agriculture Zimbabwe images”. Some of those images will have URLs to backtrack to which might be highly informative.

https://images.search.yahoo.com/search/images;_ylt=AwrExdp9_6NhZTEAL.2JzbkF;_ylu=c2VjA3NlYXJjaARzbGsDYnV0dG9u;_ylc=X1MDOTYwNjI4NTcEX3IDMgRhY3RuA2NsawRjc3JjcHZpZAMzRGNESkRFd0xqSmQySkZzWWFQeWFRVkFNakEwTGdBQUFBQ3BOU0hiBGZyA3NmcARmcjIDc2EtZ3AEZ3ByaWQDMlE2SzZxNlNTcVM5WFFNcnljeGZkQQRuX3N1Z2cDMARvcmlnaW4DaW1hZ2VzLnNlYXJjaC55YWhvby5jb20EcG9zAzAEcHFzdHIDBHBxc3RybAMEcXN0cmwDNDEEcXVlcnkDZnVtZnVkemElMjBhZ3JpY3VsdHVyZSUyMHppbWJhYndlJTIwaW1hZ2UEdF9zdG1wAzE2MzgxMzc3NDY-?p=fumfudza+agriculture+zimbabwe+image&fr=sfp&fr2=sb-top-images.search&ei=UTF-8&x=wrt

If this turns out to be as long-term useful and sustainable as we all hope, it may well enable the establishment of a strongly independent peasant-farmer type of political culture in Zimbabwe. And that might be an inspiring example to develop parallel versions of the same in other countries, perhaps even in the “shallow country inner-ring-rural zone” around some towns and cities in America.

I have a few aquaintances that farm no-till. I get a bit of business as a geologist doing aquifer tests and well design for irrigation systems, so I love to talk shop with farmers and the no-till folks are especially interesting. They always bring up these three points:

1. Less work

2. 60-80% reduction in fuel costs/consumption

3. No irrigation necessary (shucks- they’ll never be my clients).

1 and 3 get publicity, but even when talking about carbon the fuel reduction gets overlooked if it’s even mentioned at all.

Ask the farmers for more detail about how much they cut their fuel consumption/costs, they’ll usually bring up as a tangent how many tractors they were able to sell, because they didn’t need them, and how that saved even more time and money.

I’ve seen Gabe talk before, and I don’t recall him talking about fuel cost reduction as a benefit, or the cascading savings related to that. I hope he put that in the book, because that’s a really big selling point to getting more farmers to follow Gabe’s lead.

Which kind of no-till farming do your no-till aquaintances practice? Do they practice the cover crop and roller-crimper crimp and smash-down of the cover crop which Brown practices? Or do they practice the cover crop and herbicide-burndown of the cover crop which is still the majority no-tiller approach to no-till, as far as I have read?

If your no-till farmer aquaintances are using the roller-crimper crimp-and-smashdown method, then it looks like Brownism is making real progress.

What an interesting view –thanks Lambert for the useful summary, and in particular for the thoughts about peasantry and class.

I am particularly interested in the part about animals. It is clear that “nature doesn’t function without animals”. My question is: could those animals in the farm be allowed to live their long lives (and not be slaughtered and sold, and replaced by other animals)? Is the slaughtering of these animals just an ECONOMIC component of regenerative agriculture (a way to make money/profit), or is it a structural element of the processes (I don’t know –maybe younger animals contribute more nutrients to the soil, or something like that)? Is this model *structurally* compatible with a vegetarian/vegan world?

Thanks

> Is the slaughtering of these animals just an ECONOMIC component of regenerative agriculture (a way to make money/profit), or is it a structural element of the processes (I don’t know –maybe younger animals contribute more nutrients to the soil, or something like that)?

Or the older animals contribute wisdom to the younger ones. Stranger things have happened!

I have seen this question semi-addressed in some of Brown’s videos. He has stated in some of them that the tight-bunched livestock moved fast from paddock to paddock to paddock are managed that way in order to semi-replicate the effect on the plants-and-soil system that the buffalo used to have. They eat all the edible plants on a paddock equally without having time to be picky-choosy, and they pee and poo and pound the pee and poo into the ground with their walking on it.

He claims that his soil started recarbonizing faster and deeper after he introduced the cattle into his system than before he introduced the cattle into his system. But given the time ( and maybe even some money) it takes to manage their guided presence, if he killed zero of them, he might have to spread their cost in money and monetized time over the price of all the pure-plant-based output he harvests. His grain and potatoes and etc. would have to cost more. Would there be enough vegans willing to pay enough more for his plant production that he could afford to keep a zero-slaughter herd of cattle alive strictly to improve his soil with? If there are, then he could. If there are not, then he could not.

So what are vegans willing to pay to help a farmer afford to keep a natural lifespan herd of cattle on the place strictly for soil/pasture/range improvement? And are enough vegans willing to pay it to actually support a don’t-kill-the-animals farmer to maintain a natural-lifespan herd of cattle strictly for soil improvement?

( I like Brown’s videos for the content of course, but also because Mr. Brown speaks very clearly and with very few wasted words, and slowly enough that I can keep up. So watching his videos is not an onerous burden on my time to me.

For people who would find watching a number of videos to be a burdensome time-suck, I am not yet sure which videos would be the few best to watch.

Probably the book itself would be best for people who find videos burdensome to watch.)

Thanks for your response, “drumlin woodchuckles” . I have not watched the videos myself, and so your description of the process (and economic drivers) are useful.

I believe in general that the exploitation and slaughter of those animals is not justified. I was wondering whether in this particular case there was any argument for doing so beyond the economic one (and, you know, the argument that people like or need to eat meat).

I also believe that these things should not be a matter of personal choice. It’s not about whether “vegans would be willing to pay” or not. Don Quijones has an article today about Deliveroo leaving Spain because they are being forced by a new law to treat their riders as employees. He quotes a newspaper article in which Deliveroo argues against the new law:

I assume most NC readers will disagree with those statements from Deliveroo: you MUST treat people fairly, and that includes respecting (and expanding) laws that protect employees, gives them days off and vacation, etc. etc. That should not be up for discussion, and should not be left up to “the market” to decide whether those rights are respected. We would not accept as a response an argument that goes “So what are [social justice fighters / socialists / anti-capitalists / supporters of unions / NC readers / etc] willing to pay so Deliveroo can make a profit if it’s forced to treat the riders as employees?”

I know we do not agree on the basic premise (whether the use of these animals is justified or not)… and so I don’t expect we will agree on the structure of second-order argument (if you don’t want those animals killed, you should be willing to pay for that). But I thought it’d be useful for me to point out these discrepancies.

Thanks again.

PS: I realize I have done nothing here to defend my basic premise (we should not be killing these animals) … so let’s just agree to disagree on that point ;-)

You are correct in that we will have to agree to disagree on that basic premise. Here is another basic premise to agree to disagree on.

A rising tide of evidence indicates that plants are sentient beings and that multi-plant communities are super-sentient super-beings. The extreme and total difference between plants and animals has made it difficult for Euro-Enlightenment Secular Western Man to perceive this up to this point, but new research ( and older fringe research) is eating away at the lock on the door to that perception.

And some indigenous peoples have perceived that for a long time, and managed their live-in semi-wild lands based on that knowledge.

And now the basic premise: if the slaughter and exploitation of animals is not justifiable, then neither is the slaughter and exploitation of plants. Salad is murder, and bread is mass infanticide. Not to mention all the wild animals condemned to individual starvation and often species-level extinction by burning their wildland home down to grow plants to slaughter and exploit on the rubble and ashes.

man! i go dark for a week and Omicron happens, and Lambert has a thread that was made for me,lol.

i know quite a few vegans and vegetarians…even way out here in redneckland.

when i’m in production(not in last 2 years), they buy my surplus veggies and fruits…and, in explaining why i haven’t been producing the last 2 years, i go on and on about all this infrastructure i’ve been doing, for to make the place sustainable, and to curtail the inputs(manure and hay, which are all suspect, now…now that persistent herbicides are everywhere)

that means i grow animals…chickens, geese, turkeys and sheep at the moment…and i’m trying to add a couple of donkeys/burros(for manure, brush control and coyote deterrence), and a few goats(for bamboo control, mostly)…save for the donkeys, my vegan friends know i eat all the rest of them…(as well as wild hogs and deer).

while this truth is obviously pretty icky to them, they seem to understand the concept of Integration…likely since i go on and on about it.

when i export a tomato off-farm, the farm(specifically, the raised beds) loses nutrients that must be replaced…so the sheep, etc eat a bunch of stuff in the pastures and woods (all the non-raised bed parts) and convert it into fertiliser…much of which gets put into the beds.

circle of life, and all.

so long as i’m treating my animals well…and killing them as humanely as possible…most of my vegan friends can deal with it.

i’m certainly a dern sight better than conagra,lol.

just today, i raked/swept up the first dead leaves…and a great carpet of goosepoop… from under the Big Oak(where they spend the night), and dumped piles of it in all the beds on this side of the road…sprinklers going to wet it, as well as to make it like cocaine to the chickens, who will spread it out and incorporate it(and poop all over it, too…as well as eat bugs and bug eggs) over the next few days. the chickens are more efficient than me at this task…and it saves my back letting them do it.

getting my mis en place together for a single-chicken tractor building party, sometime this winter…instead of the fattening cages i had originally contemplated…because the latter would require the purchase of scratch grain…while the former won’t…i’ll stick them in the beds under production next spring/summer, and they can fatten up on bugs and grass and weeds(it’s really the running around that makes the meat tough, btw)

only problem to overcome is making the tractor coon-proof…so they can just stay in the beds for the 4-8 weeks it will take to fatten them up.

and from this Yeoman Farmer/Peasant…thanks for this sort of thing, Lambert.

Keep in mind that “no till” in industrial agriculture usually means copious herbicide superphosphate and anhydrous ammonia fertilizer application.

I am not convinced that tilling is always bad. My wife and I have experimented in our veggie garden using no till and tilling methods and have found that some stirring of the soil in springtime reduces insect pest and fungus infestations and increases plant vigor. We try to do the tilling when the weather is still cold and the earthworms are generally far below the surface. We add an abundant layer of composted manure and wood ashes followed by straw or woodchip mulch. (We keep the tilling fairly shallow using a walk-behind roto-tiller – mainly to mix the manure/ashes with the soil top layer.) Space limitations prohibit extensive use of crop rotation, but we try to move plant types around every year to reduce infestations. Over the course of the years, the mulching/manuring has generated a topsoil layer of considerable thickness. One of the plots we use has been used as a kitchen garden for over 100 years (by us and by my wife’s parents and grandparents), whose topsoil extends more than 50cm below the surface. That garden was instrumental to the survival of my wife’s family during the Second World War.

This comment re-raises the question I posed to redleg up above. Are his no-till farmer aquaintances part of the mainstream chemical burn-down no till wing of the no till community? Or are they part of the still-tiny no-chem no-burndown mechanical-physical roller-crimper crimp and smashdown wing of the no-till community that Gabe Brown is part of?

Interestingly enough, a lot of early research on crimp-and-smashdown no till has been done at the Rodale Research Institute. They have written a couple of books about that.

https://bookstore.acresusa.com/products/roller-crimper-no-till

Here is a bunch of images of various roller-crimpers on display or in use.

https://images.search.yahoo.com/search/images;_ylt=AwrE1.Bed51hROoAm_ZXNyoA;_ylu=Y29sbwNiZjEEcG9zAzEEdnRpZAMEc2VjA3Nj?p=Jeff+moyer+roller+crimper+agriculture&fr=sfp

So the roller-crimping concept and roller-crimper machines already existed for Gabe Brown to go to when he decided the petrochemical mainstream approach was not working anymore.

Here are two books by a frequent Acres USA conference presenter and certified organic farmer named Gary Zimmer who uses tillage when necessary in his particular operation system, and describes how, when and why.

https://bookstore.acresusa.com/products/the-biological-farmer

https://bookstore.acresusa.com/products/advancing-biological-farming

What can drive regenerative practices in ag? Federal Crop insurance values and payouts for organic certification are 2-3 times those for conventional farms. From a risk management perspective that is enough to allow for profitable transition. The transition period which takes 3 years is the riskiest where crops cannot be labeled organic, but organic practices must be followed.

In the drier climes, Brown’s practices must be stretched out, no roller-crimpers but mow instead or run cows. 3-year rotations with a cover crop to fix adequate nitrogen with one year of no-till, and the use of psuedomonas flourescens to control annuals cheatgrass and goatgrass. US acres in this drier regimen include most Hard Red Winter and Soft White Wheat areas with about 15m acres. https://wheatworld.org/wheat-101/wheat-production-map/

So what about the nutritional value of grains under different production approaches. https://our-sci.gitlab.io/bionutrient-institute/bi-docs/Grains_Report/

I think one very simple way to encourage more regenerative practices is simply to tax (or stop subsidising) inputs, whether its fertilisers, pesticides or feed. There are numerous hidden subsidies for these which have heavily distorted the economics of individual farms. I think the accidental surge in the price of fertilisers and pesticides we are about to see over the next year due to rising fuel prices and energy shortages around the world will do more than anything to make many farmers change their minds.

If America were to run away from the Free Trade Plantation, and were to militantly and belligerently protectionize itself, then America could apply within its own borders the Full Metal Hansen FeeTax Dividend concept and use it to price fossil-carbon based fertilizers and chemicals out of existence in agriculture within America’s own borders. We could then ban food imports from countries which fail to do the exact same thing.

About fuel for the tractors themselves? How much fuel would be needed to do the Gabe Brown thing with a tractor to pull and power the machines? How much land would be needed to grow vegetable or nut oil to fuel the tractor with bio-diesel fuel? If the amount of land needed to grow biodiesel fuel for the tractor over a whole year was a small enough percent of the land that tractor could work in that same year, then rigidly protectionized agriculture could grow all the biodiesel fuel needed to keep farming and feeding the rigidly protectionized nation.

Let America feed America, and the rest of the world feed the rest of the world. That is not possible without rigid militant belligerent protectionism. One hopes that could be achieved politically and without having to round up all the Free Trade supporters, kill them all and bury them in huge pits and trenches. Because that would be mass-politicide, and nice liberals do not advocate mass-politicide.

Rudolph Diesel did invent his “diesel” engine to run on vegetable oil, after all.

A tax on inputs would cause a revolt in farm country, bad policy idea. The only way is to incentives behaviour, i.e. practices. The surge in fertilizer and pesticides prices is no “accident”. Chinese demand a year ago started the melt-up, as it were. Now export restrictions from Russia, China, et al are fueling runups. Here’s knock on effects https://twitter.com/YETICapital99

Well, the price-rise in Haber Bosch fertilizer and now perhaps in diesel and gasoline fuel for tractors and machinery will have the same effect as a fossil input tax, but since it is a private tax imposed by the private enterprise market system, farm country won’t revolt about that in the same way.

So three cheers for the rise in Haber-Bosch nitrofertilizer prices. Here’s hoping the price on natural gas will rise so high that it can achieve the extermination of Haber Bosch fertilizer that governmental policy dare not even attempt.

And let Darwin take the mainstream petrochemical cancer-juice death-cult farmers who are too proud and reactionary to adopt Gabe Brown’s methods.

Re: “the idiocy of rural life” This is a mistranslation according to an expert on Marx (perhaps THE expert), so it says Monthly Review: https://monthlyreview.org/2003/10/01/mr-055-05-2003-09_0/

To save you the trouble of hunting through the editor’s comments, here is the relevant part:

IDIOCY OF RURAL LIFE. This oft-quoted A.ET. [authorized English translation] expression is a mistranslation. The German word Idiotismus did not, and does not, mean “idiocy” (Idiotie); it usually means idiom, like its French cognate idiotisme. But here [in paragraph 28 of The Communist Manifesto] it means neither. In the nineteenth century, German still retained the original Greek meaning of forms based on the word idiotes: a private person, withdrawn from public (communal) concerns, apolitical in the original sense of isolation from the larger community. In the Manifesto, it was being used by a scholar who had recently written his doctoral dissertation on Greek philosophy and liked to read Aeschylus in the original. (For a more detailed account of the philological background and evidence, see [Hal Draper], KMTR [Karl Marxs Theory of Revolution, New York, Monthly Review Press, 1978] 2:344f.) What the rural population had to be saved from, then, was the privatized apartness of a life-style isolated from the larger society: the classic stasis of peasant life. To inject the English idiocy into this thought is to muddle everything. The original Greek meaning (which in the 19th century was still alive in German alongside the idiom meaning) had been lost in English centuries ago. Moore [the translator of the authorized English translation] was probably not aware of this problem; Engels had probably known it forty years before. He was certainly familiar with the thought behind it: in his Condition of the Working Class in England (1845), he had written about the rural weavers as a class “which had remained sunk in apathetic indifference to the universal interests of mankind.” (MECW [Marx and Engels, Collected Works] 4:309.) In 1873 he made exactly the Manifesto’s point without using the word “idiocy”: the abolition of the town-country antithesis “will be able to deliver the rural population from the isolation and stupor in which it has vegetated almost unchanged for thousands of years” (Housing Question, Pt. III, Chapter 3).

Marx’s criticism of the isolation of rural life then had to do with the antithesis of town and country under capitalism as expressed throughout his work. See also John Bellamy Foster, Marx’s Ecology (New York: Monthly Review Press), pp. 137-38.

” the abolition of the town-country antithesis “will be able to deliver the rural population from the isolation and stupor in which it has vegetated almost unchanged for thousands of years” (Housing Question, Pt. III, Chapter 3).” . . . . .

Sure sounds like the actual growers of food and managers of eco-viable landscapes for thousands of years didn’t have any knowledge worth respecting, or even knowing, in Marx’s humble opinion. Didn’t Marx want “for” them a future as gangs of workmen on huge “peoples’ plantations”? What could an urban intellectual who probably couldn’t even tell wheat from rye or which end of the garlic is “up” possibly even know about what peasants did or didn’t know?

Thanks you for this!