This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 1552 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, more original reporting.

Lambert here: Headline should be “Have Been Doing Better,” not “Did Better.” And some would say all capital is human capital. Perhaps then the phrase “human capital accumulation” would not be so jarring….

By Simeon Djankov, Policy Director, Financial Markets Group, London School of Economics, and Eva (Yiwen) Zhang, Researcher, Peterson Institute for International Economics. Originally published at VoxEU.

Leaving human capital out of policy discussions might lead to incorrect inferences about which measures were most successful during the pandemic. Based on a sample of 45 mostly OECD economies, the authors of this column show that both high levels of human capital and, to a lesser extent, flexible labour regulation have allowed labour force participation to recover faster during the Covid crisis. Countries that prepare to fight the effects of globalisation and robotics have also managed to alleviate the effects of the shock on the labour market.

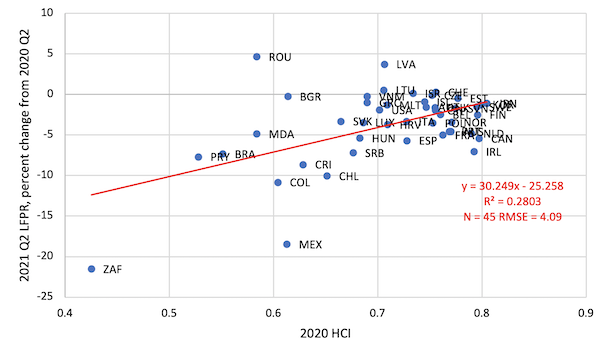

Baldwin and Forslid (2020) posit that labour markets are more robust in nations better endowed with human capital, as high-skill workers are more likely to have flexible work arrangements. High-skill jobs can also be accommodated more easily in a period of social distancing and lockdown measures. If this hypothesis is correct, the recovery in labour force participation in the wake of COVID-19 will be faster in countries with higher human capital. We find that this is indeed the case in a sample of 45 mostly OECD economies during the first year of the pandemic (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Nations with higher human capital recovered faster

Note: The change in the Labour Force Participation Rate is measured between second quarter of 2020 and second quarter of 2021. We use a measure of human capital accumulation as proxy for the share of footloose high-skill jobs in danger of moving to either other countries or being lost to robots. The sample comprises 45 economies with available quarterly data on labour force participation: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Rep., Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United States, and Vietnam.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the Angrist et al. (2021) dataset and the labour force participation rate measured by OECD, last accessed on October 30, 2021.

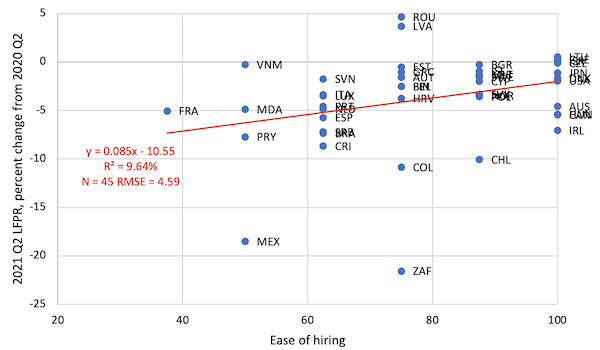

Other, more traditional forces may be at play in the job recovery process too. Since the 1980s, labour regulation has become more flexible in much of the world (Blanchard et al. 2013). The effects of this dynamic have been the subject of much empirical research, particularly in the European context. Bjuggren (2018) finds, for example, that a 2001 reform that increased labour market flexibility in Sweden also improved participation. Bentolila et al. (2012) demonstrate that the wide insider-outsider labour marker divide in southern European economies is reduced with flexible labour rules. Cournede et al. (2016) use OECD data to show that easing employment regulation benefits employment transitions, which in turn increases labour force participation. Botero et al. (2004) use a global dataset to show that flexible labour regulation brings workers to formal jobs, increasing labour force participation.

We find some support for the hypothesis that flexibility in labour market regulation aids the job recovery. In particular, there is a positive correlation between the percentage change in the labour force participation rate in the first year of the pandemic and a regulatory index on the ease of hiring (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Nations with flexible regulation on hiring recovered faster

Note: The change in the Labour Force Participation Rate is measured between second quarter of 2020 and second quarter of 2021. The analysis is performed on the 2019 pre-pandemic data on the ease of hiring, and in particular the availability and maximum length of a fixed-term contracts for permanent tasks. The sample comprises 45 economies with available quarterly data on labour force participation: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Rep., Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Moldova, Netherlands, Norway, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United States, and Vietnam.

Source: Authors’ calculations using the updated Botero et al. (2004) dataset and the labour force participation rate measured by OECD, last accessed on October 30, 2021.

We further test the human capital and regulatory flexibility hypotheses using regression analysis. Human capital is positively and statistically significantly correlated with a faster recovery in labour force participation. This is true when controlling for income per capita and ease of hiring regulation. These qualitative results are maintained if we control for other proxies for flexible labour regulation.

The coefficients on labour regulation are positive, though not statistically significant. The interaction terms between regulation and human capital are negative, but also insignificant. Overall, the results show that both high levels of human capital and flexible labour regulation allow labour force participation to recover faster during crisis. The effect of the former is, however, dominant. Irrespective of the level of regulation, countries that prepare to fight the effects of globalization and robotics have also managed to alleviate the effects of the pandemic’s shock on the labour market.

Policy advisors should take note of this result, as it may distort the inference of which labour market policies have yielded positive results during the pandemic. Initial conditions play a significant role in designing such policies, both in terms of regulation as well as – as this column argues – human capital accumulation.

This is rather dubious statistics, in my not too humble opinion. The “trends” are already weak if you assume that these data points are truly 45 independent observations of an underlying phenomenon. But If you look closer, the trend is driven by the cluster of latin-american countries, and South Africa.

That’s it. The graphs just say “labour participation went down more in Latin America than in Europe and East Asia, and yet more in South Africa”

Given that, you will get a (statistically significant!) trend for any variable that differs somewhat between Latin America on the one hand, and Europe+East Asia on the other hand.

definitions?

unless one reads all of the background literature, this thing is useless.

and then we must agree as to what exactly constitutes “high skill” labor, human capital accumulation (what & how?), and what are exactly “flexible” labor policies. oh, and we won’t count any other huge and myriad variables like development level, major resource or production modes, demographics, or the million other policies which may affect “labor force participation”.

a writeup so intangible, it floats on air. my professors would have failed it for not explaining these things and the authors’ understandings of how the concepts apply, then simply citing jargon. but that was them and it wasn’t economics, the anti-social “social” science.

Um. This looks very much like the stuff put out by stock broking firms in the 1990s. The giveaway is “to a lesser extent, flexible labour regulation have allowed labour force participation to recover faster during the Covid crisis.”

The statistical science here is non-existent. This analysis was produced in an Excel spreadsheet. I’d have been ranting even if the R-squared was close to 1.0. But here sadly it is not.

Who are these people? What planet do they live on?

These guys don’t know how to fit data. R2 = 9.64 is not a correlation. You can draw a line any which way with thses points.

Yes! When I read that article, my first thought was “What am I missing?” because an R2 of .28 or .09 seems to imply that y is barely dependent on x so it doesn’t seem to justify their conclusions that: “Overall, the results show that both high levels of human capital and flexible labour regulation allow labour force participation to recover faster during crisis.”

Wouldn’t you want an R2 of .5 or higher to validate their hypotheses?

I’m not a statistician but those graphs seem to be no more than simple algebra: y=mx+b with linear curve fitting to find b.