Yves here. Americans outside the private-jet-using class have no idea how poor they are compared to the middle classes of most other advanced economies. They are not overpaying for lousy health care. They have solid social safety nets and an at least adequate level social services (child care, elder care, public transportation). And they generally prefer to have less housing and more vacation. Matt Bruenig explains how the comparisons of incomes that the US is wont to use conveniently obscures all these issues.

I got an odd reminder of the state of the US earlier this month when I went to New York City to see doctors (I wore an N95 with a procedure mask underneath and kept them on in transit, which was not pleasant). New York looks…tawdry. It’s not as down and dirty as it appeared after the fiscal crisis, when I first moved there, but it is also lacking in the sense of steely determination that I felt then. There was manufacturing in the Garment District. Soho was largely empty, and most of the artists had not exactly legal rentals, and far from legal improvements. There were plenty of other aspiring talents, singers, dancers, thespians, who were able to live in Manhattan, in areas like the Lower East Side, or Hells Kitchen, or Spanish Harlem.

But in the later 1980s and through the last decade, the city was gentrified. More upper income parents decided to raise their kids in Manhattan rather than decamp when their offspring hit school age. I saw it in my building; it had only one child when I arrived, and by the time I left, there was a good half dozen. Bodegas and “Koreans” (24 hour convenience stores) lost out to chichi food vendors and chain drug stores that carried the 2AM essentials: cigarettes, condoms, painkillers and cough syrup, milk, butter, eggs, toilet paper, diapers, and batteries. Big box stores, coffee shops, and bank branches displaced quirky retailers. And everything got shinier: spiffier storefronts, virtually no graffiti, tidier streets, even much faster snow plowing.

As much as seeing how the fall light hit the buildings and the yellow gingko trees made me nostalgic, the damage the city has suffered is visible despite the streets being crowded again. The bizarre Covid theater of quickly-built fake outdoor rooms attached to restaurants are eyesores and disrupt foot and even car traffic. The “build it and they will come” bike lanes are barely in use, and the rental bike racks are virtually all full. Many store fronts are boarded up and graffiti-covered. Even some of the Christmas decorations looked tatty; the city installed large package props on Fifth Avenue sidewalks, but their LED lights look cheesy. And even hardened male natives tell me the subways aren’t safe.

I still very much miss New York, so it is sad to see the city in this condition. But some of the horses on Central Park tourist duty were wearing pretty plumes and strutted as if they were proud to be decked out.

By Matt Bruenig, a lawyer, policy analyst, and founder of the People’s Policy Project. Originally published at his website

Comparing incomes across countries poses certain difficulties: incomes are paid in different currencies, products have different prices, tax levels are different, and benefit levels are different. Many years ago, economists came up with a decent-enough way to cut through most of these problems: figure out the prices in local currency amounts for a given consumption basket and then compare those prices across countries to determine how much a given unit of currency is worth relative to the US Dollar.

This is called Purchasing Power Parity. And it allows you to say that, e.g., 1 US Dollar is equal to 7.985071 Danish Kroner. With this knowledge in hand, it becomes possible to see, e.g., how Danish GDP stacks up against US GDP or how the median Danish income stacks up against the median US income.

Last year, Denmark’s PPP-adjusted GDP per capita was $60,551. In the US, the same number was a bit higher at $63,543.

In 2017, the last year the OECD has data on the subject, the median disposable equivalized PPP-adjusted cash income in Denmark was $30,739. The same number in the US was $35,600.

This figure is the best one we have from the OECD, but it suffers from one very big flaw: it subtracts the taxes people pay from their income, but does not count any of the non-cash benefits they receive towards their income. This means that the taxes the median Dane pays towards public health insurance, child care subsidies, and free college are deducted from their income, but the value of these benefits are not then added back.

It’s hard to say exactly, but based on the LIS microdata that I worked on many years ago and these current OECD statistics, it’s pretty clear that the bottom 60 percent or so of Danes have a higher total income (when including in-kind benefits) than the bottom 60 percent of Americans. Once you get over that line, the US pulls ahead of Denmark, at first modestly, but then enormously as you approach the top of the distribution.

This may be a boring way to approach this question, but I assure you it beats certain other approaches to it.

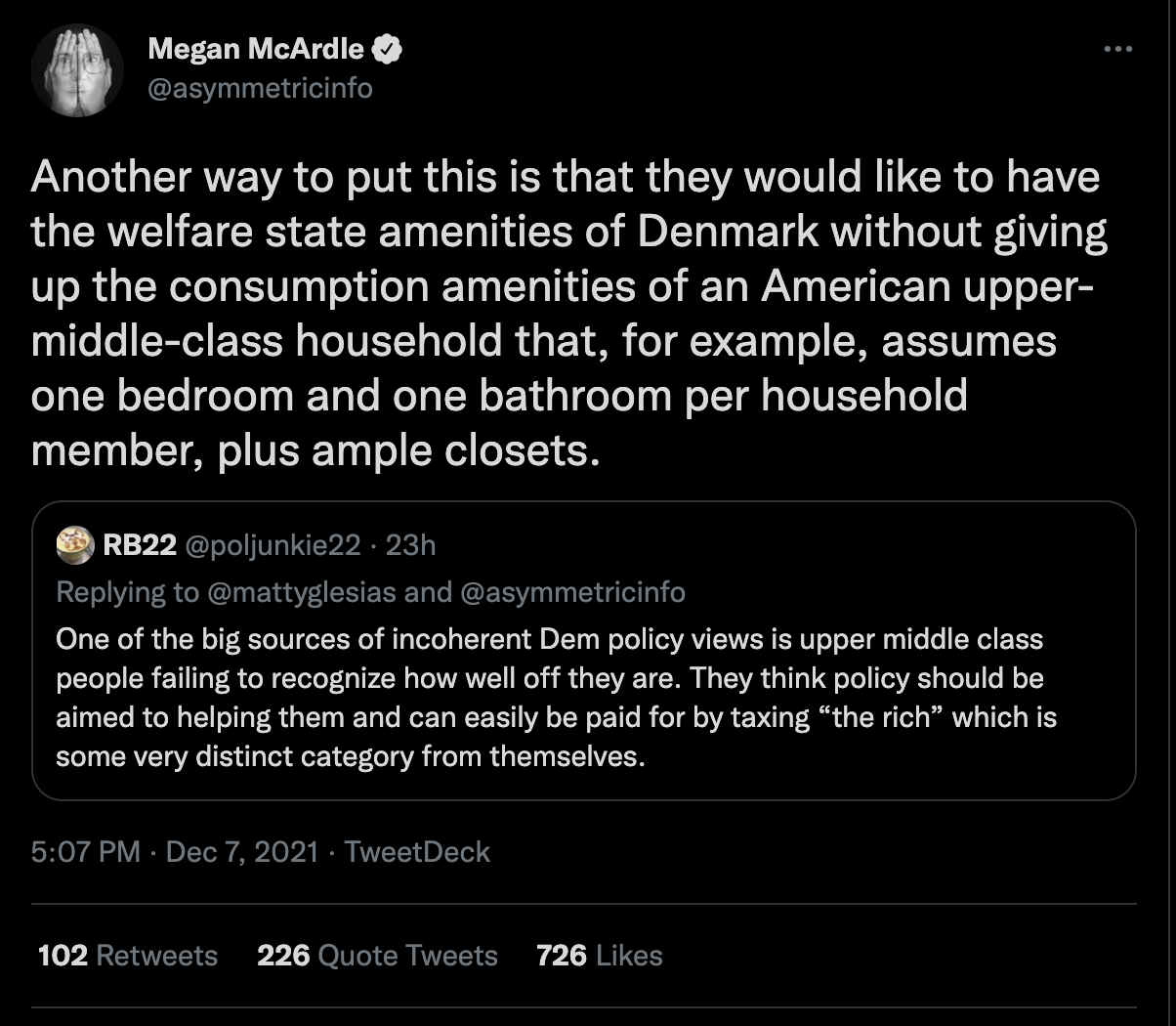

Elsewhere in this and adjacent threads, you see people talking about how Danes or other Europeans often don’t use various American appliances or consume fewer quantities of certain other consumption items.

The obvious problem with this analytical approach is that there are many reasons why someone might have a differently-sized house, different appliances, and a different temperature on their thermostat that are not related to their general level of affluence. This is why we don’t try to compare different places by focusing on the quantities of one or a few specific consumption items, but instead focus on their incomes as compared to the prices of the consumption basket.

Danes clearly have enough income to buy dryers. They only cost a few hundred dollars and last ten years. Remember, this country’s PPP-adjusted per-capita GDP is nearly identical to ours. If you want to figure out why they may not have them despite their clearly documented affluence, ask yourself why do Americans not have Japanese-style toilets despite their affluence? Why do we not have French bidets?

Judging by the toilet situation, we must be a pretty poor country. Or maybe it’s just that different societies develop different consumption habits over time and that picking on any given one of them is not terribly illuminating when it comes to figuring out their overall level of income and purchasing power and that instead you should use a more comprehensive measure.

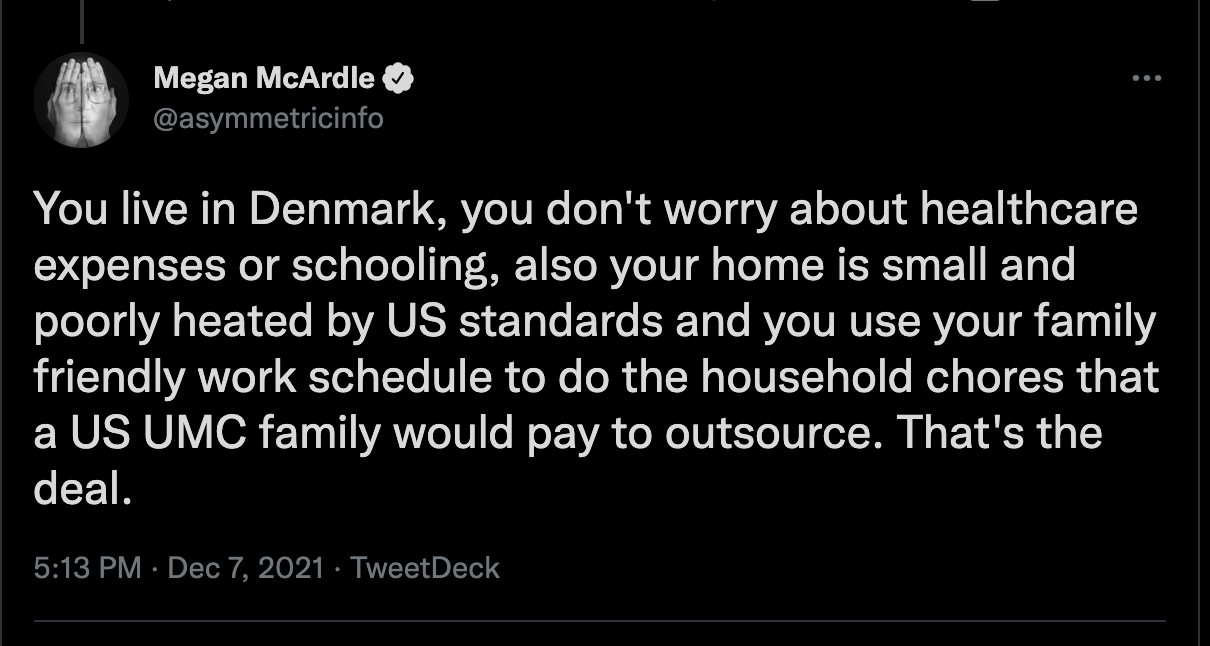

McArdle’s second tweet is particularly amusing because it begins by complaining that Danes have smaller homes on average, but then pivots to saying that the 421 hours of extra leisure time that Danish workers have each year should be disregarded because they have to use it to clean their houses instead of hiring maids. If only there was a way to work fewer hours and spend less time cleaning your house, perhaps by having a smaller house…like Danes have?

Poorly heated homes is a new one to me. Denmark is known for its extensive district heating systems. Maybe a country that is further north than Edmonton is just more comfortable with colder indoor temperatures and is not secretly poorer than the statistics suggest.

Don’t get me wrong. If people want to poke fun at the consumption patterns of other countries or even other regions of our own country, that can be good fun. Europeans seem to have a fun time with American chocolate, cheese, and beer. So by all means have a fun time with their bland food or small fridges. But in doing so, it’s best not to talk yourself into thinking that consumption patterns that differ from your own indicate a lack of prosperity.

When it comes to the “upper middle class” in America, which we might define as those who are significantly above the point where US income exceeds Danish income in the overall income distribution (say 75th percentile and thereabouts), the comparative question would have to focus on whether other considerations might outweigh lower incomes.

The universal welfare state really does provide benefits to everyone even those who are not net beneficiaries of redistribution. For those people, the main benefits of the welfare state are that it smooths out lifetime incomes and protects you from steep income drops.

Every time one of those “$200,000 is not a lot of money” articles drops, if you look closely at it, what you’ll almost always find is a detailed budget of someone who is currently shouldering a lot of expenses or savings that would be smoothed out by a tax-funded welfare state in other countries. So the budgets will usually be dealing with one or two child care bills while also putting significant savings towards 401k retirement accounts and 529 college savings accounts.

At some point these costs will level out for this person: the kids will move on to K-12 and the 401k and 529 will be well-capitalized. At that point, they will be rolling in big time cash. But at that moment, they seem to opaquely be grasping that a system with higher taxes, child care subsidies, more generous old-age pensions, and free college would result in them having more money to spend at that point in their life, which means they are opaquely grasping that the smoothing function of the welfare state has a lot of value even for those with higher incomes.

The higher amount of leisure time might also factor in depending on your own personal preferences. Being able to take off an entire month in the summer and have more vacation and holidays in general is worth a lot to some people, which is why countries like Denmark have implemented these policies. Despite what McArdle says, it isn’t actually the case that all of this extra free time is spent cleaning.

Beyond that, there are of course various indirect quality-of-life aspects of an egalitarian society. There is much less crime, homelessness, “blight,” and things of that nature. Upper middle class people can often insulate themselves from that stuff in highly unequal societies, but not entirely, and the amount of time and money spent on insulating oneself from the consequences of inegalitarianism can also be a bit of a drag. Finally, you might even just care that other people in your society have good lives for less self-serving reasons.

The dryer thing is such a weird hill to die on and usually seems to be based upon some anecdote about traveling in Europe one time. My other had a dryer in the early 80s. It’s not a luxury item in Europe, and the best dryers are made by European manufacturers. People just make different choices about what they want.

On the other hand modern US construction is really bad. American houses are built cheaply, are poorly insulated and will not last. Excluding Britain (which suffers from the same disease as the US), northern European houses are much better built than American houses. Danish houses are really nice. The Germans invented the PassivHouse for god’s sakes.

Meghan Mcardle

Truly the hack’s hack. Most Americans can’t afford maids either, but sure that’s a reasonable comparison to make…

Another example of hidden costs of construction from east Alabama.

Recently I had an assessment of several heaves in a concrete driveway and got an assessment of a fix-up. During the conversation it was noted that the concrete in my driveway had a life-expectancy of 75 years (laid in the 1970s) whereas recent concrete driveway replacements in the neighborhood during the past 5 years had a life expectancy of 15 years. Apparently the river aggregate used in earlier concrete versus the lime-heavy concrete today contribute to different life expectancies

I live in London UK and have a drier in my house by accident- previous tenants couldn’t take it when they moved. I haven’t actually used it in 3 years. The damn thing is annoying and loud and I would rather use a drying rack.

I think Americans like dryers only because they can hide them in a far corner of a deep basement of a giant house.

I admit to hiding my Kenmore dryer in a far corner of the deep basement of my not-giant 2-family house. But I must point out that it was about 30 years old when I purchased it for $100 with a one-month unconditional guarantee 25 years ago. It’s noisy, and not pretty to look at, but it still runs just fine. I find it far preferable to hanging all the clothes, bed linens, towels, etc., on clotheslines in the basement or outdoors. And it does testify to the fact that once upon a time, American appliances were built to last.

American here. I am actually more embarrassed by my underwear on display in the dining room (only place the rack won’t get in the way).

If you only dry underwear and socks, 15 minutes can be enough.

The shirts and trousers I dry on their hangers in my closet, because the clothes dryer damages them.

My parents with seven children at home, which meant lots of clothes washing and drying weekly, found it useful to have a drier, and it was indeed. There are now washing machines that work also as driers so there is no need of extra space for that item. At our home nowadays, with my family of four, with two no-longer-children at University we don’t feel any need for a drier except if we want a higher electricity bill (not the case). Our offspring both go to university, not totally free, but we wouldn’t be able to afford US tuitions by any chance. None of them are getting indebted for that reason. Given the case we might pay them postgraduate studies here or abroad if we think this is needed. Our medical expenses have been close to 0 (a few inexpensive medicines) even if my wife is frequently screened for skin cancer plus some other stuff and she recently had a melanoma removed at 0 cost included all the processes before and after. Covid tests have cost us nothing (only an antigen kit I bought just in case). For 20€/month our students can take any bus/metro in Madrid, a bit more expensive if you add city outskirts. We have only one car that we share between the four of us and really no need of a second car. I do most of my stuff without needing it, I mean the car. Only use it for the supermarket (once a week) and the gas station the very same day I go to the supermarket but only once every 2-3 weeks. You see, two of my family roles. I spend about 140€ weekly on the supermarket and everybody is having breakfast, lunch and dinner at home every day with few exemptions. Yours truly is the chef most of the time. On weekdays a few purchases like daily bread. Unfortunately we are now living on our savings though hopefully this will change soon on my side. My wife can do it until she dies and yet let her son and daughter a handsome inheritance. This means we are in ‘no extra costs’ mode by definition except for son and daughter needs. Next Christmas we will spend a few days in our second home at the beach (a luxury courtesy of wife’s parents).

If I now had a wage of about 63.000$ I would be saving much of it, most of it.

Building houses in wood is rare in Denmark. We use bricks which also means that a house, if taken care of, would still around in a couple of centuries whereas a wood house would likely be gone.

More expensive building materials do play a role in house sizes

I lived in southern Sweden near Denmark in a house with a drying closet rather than a dryer. It used the small closet space under the stairs that included a dehumidifier and a small warming element. Hang the clothes up and they are dry 6 or 8 hours later without any wrinkles. More energy efficient and less labor than using the American style dryer.

Denmark is tiny. Smaller than Ireland. Yet it always comes up for comparison. But if we look at size, instead of “income”, it gets clearer. They are small and tidy. We are big and sloppy. It is more “expensive” in every way to live in a big sloppy country. It would be much more salient to compare a US state, of approximately the same population, to Denmark. I’m guessing around 5 million people. And to look at the opposite end, to compare the US to India is equally difficult. Just to really bring the silliness of these comparisons home, let’s compare Denmark to India. Right? It should go without comment that a country should never get so big, sloppy and out of control that it cannot maintain good social welfare; that it casually destroys the social contract.

When you stress Denmark’s small size compared to the United States, Susan, do you mean to say that Denmark’s universal social welfare policies cannot be scaled up? (I always wonder what people mean when they say this and they do often say it, at least to me).

As far as the USA being “big and sloppy” and therefore more “expensive” [your quotation marks], according to Google, its tidiness and small size, notwithstanding, Denmark’s cost of living is a full 28% higher than that of the USA. https://www.mylifeelsewhere.com/cost-of-living/united-states/denmark

I think it’s that democracy and decent self-governance can’t be scaled up to a bigger size. The population and landmass that has to be governed is just huge, a Senator in California represents 8 times the population of the entire of Denmark.

And the social welfare programs, well yes that would be good, but it would be most likely to follow from a functioning democracy, and I’m not sure that scales very well.

The first thing I would wonder is, How do you compare value received (the cost of living) in a small, well run country with that of a big hopelessly inefficient country? Cost of living is a balancing act between supply and demand on an economic scale. It might be made more expensive by any number of middlemen taking a cut for totally pointless services (fees), etc. My guess is that if we could break down the “cost of living” into actual value – not just the price of various things, many of which have been unnecessarily made into necessities (commuting nightmares and other stuff we ignore) – we would discover that the US keeps the price of gasoline (and other things) down so everybody can waste it along with wasting time on the freeway. And on and on. Don’t get me started on “health care’.

Since Breunig is particularly interested in Scandinavian social democratic societies, he often deals with this objection that countries like Norway and Denmark are much smaller than the United States, and thus there’s no point in turning to them for positive examples since their situation ‘does not apply’ to the U.S. The guy is a lawyer with a background in debate, and you can find his discussions on this topic in many places. Try the People’s Policy Project site; I’m pretty sure there’s also an episode of his podcast ‘The Breunigs’ on this topic.

Having been self employed for 30+ years, with 3 children to raise and educate, and self-funding retirement, paying maximum FICA, extortionate Obamacare premiums ($22K out the door before they pay a penny) and high NYS income taxes… well, you add it all up and we were effectively paying French or Danish taxes without the benefits.

With a disabled son, we’re basically on our own providing care. Parents have passed on and required first expensive home care services and later nursing home “care”, costing many thousands per month. And some types care for disabled or elderly simply cannot be gotten.

The US is a failed state… Rentiers, MIC, GWOT and COVID are the only proof we need.

upstater,

That’s right, we pay dearly and get bupkis back. But we get big dryers, huge fridges, $75,000 trucks, shoddily built McMansions and collapsing infrastructure. We get student debt and medical debt. We get teensy vacation time. No childcare or eldercare support. But those great 3% mortgages!

I agree we have a failed state. The question most on my mind, is that when a state collapses, does it do so with a bang or a whimper? Quickly or generationally?

I suggest giving Dmitry Orlov’s presentation on the relative strengths/weaknesses of the USSR and USA in facing a complete collapse.

from the text:

“I’ve described what happened to Russia in some detail in one of my articles, which is available on SurvivingPeakOil.com. I don’t see why what happens to the United States should be entirely dissimilar, at least in general terms. The specifics will be different, and we will get to them in a moment. We should certainly expect shortages of fuel, food, medicine, and countless consumer items, outages of electricity, gas, and water, breakdowns in transportation systems and other infrastructure, hyperinflation, widespread shutdowns and mass layoffs, along with a lot of despair, confusion, violence, and lawlessness. We definitely should not expect any grand rescue plans, innovative technology programs, or miracles of social cohesion.”

Closing the Collapse Gap

I understand the date of that presentation is 2006 but the oil industry has fundamentally changed in the united states, we have more discovered reserves than ever. Those aren’t going anywhere. But the people could, if we regulate it away over a few generations the knowledge to tap those resources will be lost. Than when we need them the most (in the officially collapsed state) it will be an issue.

Not saying I am against environmental regulations but our vast resources in our country are always there as a back up plan. In the interim we have closed production of them within our borders and instead have invested in international companies doing the same thing (not in my backyard environmentalism).

His comments on flood of refugees from suburbia seems absolutely true. I have a multi year plan to go solar and get cars to run off it. I am on the outskirts of a major city in the hills and understand that if I cant get transportation figured out I will be one of those refugees.

Very interesting presentation thanks for sharing.

Making any sort of comparison is notoriously difficult, especially as some choices are cultural rather than economic. Even within countries there can be enormous difficulties – the quality of life for, say, a mid ranking college lecturer in parts of the north of England are vastly higher than one in the south-east, mostly due to the difference in costs for housing. A lecturer friend of mine from London used to talk with amazement about the huge Edwardian house in a good area he could buy when he moved to Liverpool after a long period teaching in China – he simply couldn’t afford anything but a very modest apartment or crappy semi-D in a bad area in London.

Low income housing can (with exceptions) be of very high standards in parts of Europe. I’ve visited the families of first generation low income immigrant friends in Stockholm and Amsterdam, and by local standards they are way out in the outer suburbs, but their homes were small but with a very high quality finish. They might be far out in the sticks, but public transport was generally very good. Much the same applies in Austria. Certainly much better than anything equivalent I’ve seen in the US, or for that matter in Ireland or the UK.

There is a cultural element. Japanese people I know in the UK and Ireland complain constantly (albeit very indirectly) about the cost of accommodation and the crappy fittings and the lack of decent baths, while expats i know in Japan complain about the minuscule apartments and the cockroaches and the very over-concerned (if polite) neighbours. Tokyo is surprisingly cheap for rent compared to most major cities, and even crappy parts of Tokyo are well served with public transport and amenities and are very safe. But you pay for this with high prices for food and homes that would be smaller than most US garages.

I know of an Irish couple, both high level IT engineers, who work for a very big name company. They were well paid in Dublin, but complained about costs, especially buying a house. They were moved by their company to London, where they doubled their already high salary. They found they couldn’t afford a house in the sort of area that would get them entry to the schools they wanted for their three children. They were then offered yet another doubling of salary to move to the San Francisco head office. By any objective standards they are very highly paid (but not ‘wealthy’, in the sense of not having any real assets) – together well into a 6 figure income. But they were shocked to find that in SF they could only afford what was considered a very modest home a long commute from their office. They have an enormous mortgage now and would be in deep trouble would one or both of them lose their job or the property market collapse in SF.

RE: ‘Built it and they will come NYC Bike Lanes’

Yves, I have one small quibble:

As a daily NYC bicycle commuter I must take exception to your comment that the bike lanes and bike share system are “barely used.”

Citibike is the most used bikeshare system outside of China and recently set a new record for ridership back in September:

https://ride.citibikenyc.com/blog/citi-bike-breaks-single-day-ridership-record-during-tropical-storm-recovery

The bike lanes are jam packed at rush hour in midtown and it’s gotten so tough to get/return Citibikes at rush hour that Citibike is trying to add infill stations to cope:

https://nyc.streetsblog.org/2021/11/02/asking-for-a-friend-is-citi-bike-being-held-hostage-by-dot-fear-of-inconveniencing-drivers/

If anything, NYC needs more bike share and bike infrastructure.

Strongly seconded.

Moved from Austin where I biked in 86, left my bike on the street after several months: suicidal to ride and to ungainly to live with in the glorified closet I could afford.

Started riding 6mi to work in 2014 and the bike lanes are an exponential improvement. Ridership is ballooning. The new traffic deck level bike lane on the Brooklyn Bridge, while requiring me to suck more fumes, has ended the “omnidirectional tourist risk” that was the bane of crossing: all of my NYC bike accidents have been with pedestrians (which I very frequently am on the bridge myself, so I’m more cautious and understanding of them than the garden variety “angry biker”) suddenly turning into the lane without looking, once even jumping backwards from the guard rail onto my handle bars blindly.

Bike lanes always look emptier than car lanes because they are far more efficient. Bikes move through them at a regular speed, they rarely stop or back up. The Chinese discovered this the hard way when many cities removed the traditional inner bike lane to make more room for cars. It made congestion much worse.

Thanks, yes, compression (red lights, traffic, acceleration…) affect cars far more than bikes

Amsterdam’s dedicated bike lanes (with traffic signals) are heavily used. Terrain is flat, unlike Edinburg where cyclists struggle to get up that hill in the center. So, maybe that’s an issue.

Amsterdam bike lanes have what is known as a ‘green wave’. Biking into the city in the morning, if you get one green light, you get them all. And when it snows, the snow on the bike tracks gets cleared first.

I was just in NYC. Cabbed all over the city, including 1x each at AM and PM rush hour. 12 trips total. Saw completely full or virtually full rental bike racks (at most 2 bikes out) and no joke, at most 10 cyclists, including a motorbike illegally using bike lane. Saw similar non-use when I was there in Oct and cabbed extensively due to location of my docs (above and below Midtown). And the weather was fine, in fact last Tuesday was balmy.

September is best weather and peak tourist season. Generalizing from that is bogus.

Lots of small motor bikes use the lanes.

Some bike docks are poorly located and some routes more heavily trafficked than others. It’s also highly seasonal and “nice day” specific.

I ride year round and am growing a distaste for nice days due to bike traffic. Anecdata: September visit to my doctor on 26th just off Lex, riding back to 80 Pine down 3rd ave to Bowery was more or less continuously passing bikes or being passed by ebikes the whole ride.

Not anything like China, maybe half what I’ve seen in Rotterdam, but still probably around a hundred other bikes on that one ride. Building the lanes is generating traffic.

100 I passed, or passed me: mid day a steady flow of a couple bikes per block, every block. The lanes are only 6’, so that’s decent traffic. On a nice spring day, Hudson River Park is unridable except at tourist speed.

It’s also generational, younger coworkers are discovering it’s a virtually free way to get around and much more predictable travel time.

I understand that those in finance always seem to have money as their unit of measure. I believe that the gist of this post is that it strives for a quality of life exchange rate, in terms of currency. In my experience this can never be a meaningful comparison.

In the United States, historically it is taken for granted that individuals are responsible for their costs for child care, health care, education, and much of their retirement. There can be no meaningful measurement of these costs as they depend on what economic level you born to and raised in, how healthy you are, and how well you avoid unforeseen catastrophes. Blending the costs of these events to create a livability exchange rate serves only to dilute the destitution at the lower levels of American society.

I believe a better measure to be our labor, specifically what lifestyle does a certain number of work hours provide? Compare this to the big flaw below:

The non-American benefits that complicate the equation in terms of “adding them back”, where in both American and non-American cases they can more closely be considered included in a person’s unit of work.

“Judging by the toilet situation, we must be a pretty poor country.” We are and not just from a monetary standpoint. You just feel clean after using a Japanese toilet/bidet. Whenever I returned from a trip to Japan, I felt like returning to a third world country.

Costco usually has a washlet for 200 bucks around Xmas. Easy to install. Not as good as Toto of course…

The simple point, I think, is that income is income and standard of living is standard of living. Neither is the same as GDP per capita, whether calculated by PPP or not. So the author is comparing apples, oranges and pomegranates. In the end, I’d argue that standard of living is the only important measure, and the only real way to calculate that is to take income minus all taxes and minus all services (health, education, transport etc.) and see how much discretionary income people have left. Though I’m not sure even that tells us a great deal about what different societies are actually like to live in.

Yves, next time you’re in New York, get out of Manhattan. There’s much more vitality in the outer boroughs. Sidewalk traffic in Brooklyn, the Bronx and Queens got back to (close to) normal much faster than in Manhattan.

Yves,

Your intro brought a real twinge to my heart.

I lived on and off in New York from the 1970s to the Naughties, mainly in Brooklyn Heights in the Joey Gallo / hookers trolling Atlantic Avenue era, and spent a lot of time in the Alphabet City demimonde.

Yes, there was AIDS (then called “GRID”) and crack, but there was a liveliness and sense of community, the Tompkins Square squats. The artists and musicians, then local figures strolling around Loisaida, are now household names.

When IKEA opened in Red Hook, Joey Gallo’s old stomping ground, I knew it was the beginning of the end. And then there was the sudden flourishing of dark-skinned women pushing blonde babies in very expensive strollers. The final omen was when I was doing yet another term of jury duty. The case involved two Italian contractors on Van Brunt disputing a steel building. In the voir dire, when the judge asked if I had anything further to say, I responded, “Yeah. I’m amazed two Italian guys in Red Hook are settling their differences in court rather than one of them ending in a swamp somewhere.”

Dismissed.

Pardon me if I’m being un-PC.

A few months later, we were gentri-fried [sic] to Jersey City.

When I was bemoaning how much I missed in the old hood, another gentri-fried friend patted me on the shoulder, and observed, “We didn’t leave Brooklyn. Brooklyn left us.”

Yves, you didn’t leave New York. New York left you.

“Finally, you might even just care that other people in your society have good lives for less self-serving reasons.”

Oh, come now Matt Bruenig , you know there is no place in economics for sentiments like that.

With housing, medical care, and food being unaffordable for millions of Americans, I am not getting whatever metric people might be using for comparing income. Here in the States, the wealthy are effectively given money while growing millions are threaten with homelessness and hunger while unable to buy medicine like insulin.

These debates over how to compare income are just distractions from the growing mass of the hungry, sick and dying in one country and those who have the necessities of life. If you can’t afford food, clothing, shelter, or medicine hearing some whinging about house sizes or doing housework is just inane. Hell, I can afford them (now) and I still find this discussion showing how embubbled too many people are.

No doubt being poor in USA truly sucks, is expensive, and very stressful. And to be part of our shrinking middle class… …well, then you gotta worry about becoming poor.

What do we get for our tax dollars? Smirks, lies and platitudes from “our elites.” And what do they get? More tax breaks.

I’ve travelled much of the world, and I’ll wholeheartedly agree with what other travellers note: the USA is a 3rd- world s#!thole, an unholy mess of selfishness, debasement, and want, and not getting any better.

If history is any example, it should come as no surprise as to what might come next.

Well finally a clear methodology of comparing incomes across borders.

Although as the comments point out there are significant cultural differences perhaps this method of comparing incomes will help lay the constant big lie of ” We cannot compete with Country X. The wages there are much lower.”

This is of course a lie, a big one.

Anecdotal data, the power is out here, and posting links using just the smart phone is a big PITA, so no links.

I saw an article where the covid suvivor got the bill – it was $1.2M. How many of those just got handed out in Denmark?

A co-worker ended up in the hospital for three days while out of town. Got a bill for $75k after insurance (and company provides excellent health insurance), and it immediately went to collections. He’s finally realizing American health insurance sucks.

Off topic, but please don’t wear anything under a N95 since this might interfere with the seal and the risk is entirely in side leakage and not through the material. The mask information from the CDC has been criminal.

No, I have to advise the reverse for a lot of cases.

Just about no one outside a medical setting has a “fitted” N95. It is only “fitted” n95s that actually produce N95 protection. You may or may not get that from the N95 you buy.

Women have shorter faces from eye sockets to jaw. I find with N95s that they all have gap under my chin and leak there. I have to wear a procedure mask underneath. When I do, breathing is sort of difficult (a sign of a fitted N95, surgeons who wear them complain that using them more than a half hour to hour is hard) and I can’t smell things in the room (I once took off my gear in a garage to wipe my nose and only then could I tell it stank of gas fumes, for instance).

Well, if you are really confident that you’ve achieved a good seal there probably isn’t any harm in it, but it’s most likely still more uncomfortable than it needs to be. I’ve been using these:

https://www.3m.com/3M/en_US/p/d/v101213340/

for my current 8 hour in person office work. That adjustable noseclip works pretty well and at least I’ve never had issues with glasses fogging up, even if I cycle to work.

Sorry if this sounds like product placement.