Yves here. It’s disheartening to see yet another article treat inflation in the US as something that can be tamed by interest rates. The Fed using its brakes is instead more likely to reduce growth without doing much to remedy inflation.

One of the big inflation drivers is energy costs, which are up due to Covid whipsawing demand, and some producers, particularly in the oil arena, not being able to turn on a dime. The auto industry chip shortage has improved but is not fully over. Food is another category where prices are up, and that’s due to many factors: poor harvests, high fuel costs, trucker shortages, and higher labor costs. The Fed can’t fix any of those.

The usual economists’ assumption, that higher prices will elicit more supply, isn’t working for US workers. A big reason is many who have real estate and/or stock market gains and face Covid risk in their jobs have decided to pack it in. Even for lower paid-hourly workers, many have decided to shift to less risky work or cut back hours because they see employers as not paying enough for them to endanger their health (and not backing workers in keeping unmasked patrons out and improving ventilation). The Fed playing with interest rate dials won’t have any impact on this dynamic.

But the wee problem is that this article, which uses the sort of models the Fed uses, shows that US inflation will stay high-ish by recent standards, which means the central bank thinks it must Do Something despite its impotence with respect to this bout of inflation. Also note the angst despite quite a few economists saying during the years of the dread Secular Stagnation that an inflation target of 2% to 4% would be better for groaf than 2%.

And don’t get me started on the model assumptions.

By Jasper McMahon, Director and co-founder, Now-Casting Economics; Lucrezia Reichlin, Professor of Economics, London Business School. CEPR Research Fellow and trustee; and Giovanni Ricco, Professor of Economics, Warwick University; Chercheur Associé, OFCE-SciencesPo. Originally published at VoxEU

The Federal Reserve has recently changed monetary stance and signalled a faster than anticipated pace of monetary tightening, while the ECB is more dovish. This column applies a statistical model to recent data on oil prices, inflation, expectations, labour markets and output, and finds that the model’s forecasts support the difference in stance of the two central banks. Based on an assessment of cyclical inflation being mostly driven by transitory energy price disturbances and a very small Phillips curve contribution in both jurisdictions, it predicts that in a year from now euro area HICP inflation will still be below the 2% target, at 1.75%, while in the US CPI inflation will be above, at 2.75%.

Inflation is the topic of the day. In the US, the Federal Reserve has recently changed monetary stance and signalled a faster pace of monetary tightening than had been anticipated. The ECB is more dovish, but a change in its assessment of inflation risks was expressed in the announcement following its December policy meeting along with a forecast that inflation will remain elevated throughout 2022. Yet, the two central banks continue to regard the current bout of inflation, although more persistent than expected, as temporary.

Is this view consistent with the data? How high is the risk that the rise in inflation may dis-anchor expectations and threaten price stability?

The conventional view shared by central banks and others is that inflation is the product of three components. First is a cyclical component related to slack in the real economy (the Phillips curve). The second is a more volatile cyclical component related to energy prices, which is driven in part by commodity price shocks and in part by the effect these shocks have on consumer expectations. The third is the ‘trend’ component, which we can think of as the underlying inflation rate that would prevail if the cyclical components were zero.

This underlying trend component relates to firms’ and consumers’ long-term expectations, which in turn should be determined by the central bank’s policy target. As long as these long-term expectations are anchored by a credible central bank target, the trend component of inflation will be stable – at the target rate. If expectations become dis-anchored then there is a danger that the stable equilibrium will be lost, and the central bank will have to intervene more and more forcefully to re-establish the credibility of the target.

From this perspective, if central bankers say that the current inflation is transitory, they presumably mean that the trend component of inflation is at the target rate – i.e. around 2% – and they expect the inflationary pressure to abate even without policy intervention. Although the two cyclical components – the Philipps curve and energy price disturbances – are temporary, there is a danger that they can destabilise inflation if they affect long-run expectations. In particular, oil shocks have historically induced surges of inflation expectations, and are thought to be able to dis-anchor consumers’ and price setters’ expectations (Coibion and Gorodnichenko 2015, Coibion et al. 2018).

How can we determine the current level of the trend component of inflation? We look at the data through the lens of a statistical model proposed by Hasenzagl et al. (2020, 2021). This model is an attempt to characterise in a stylised way the conventional view of inflation described above.

The Underlying Inflation Rate

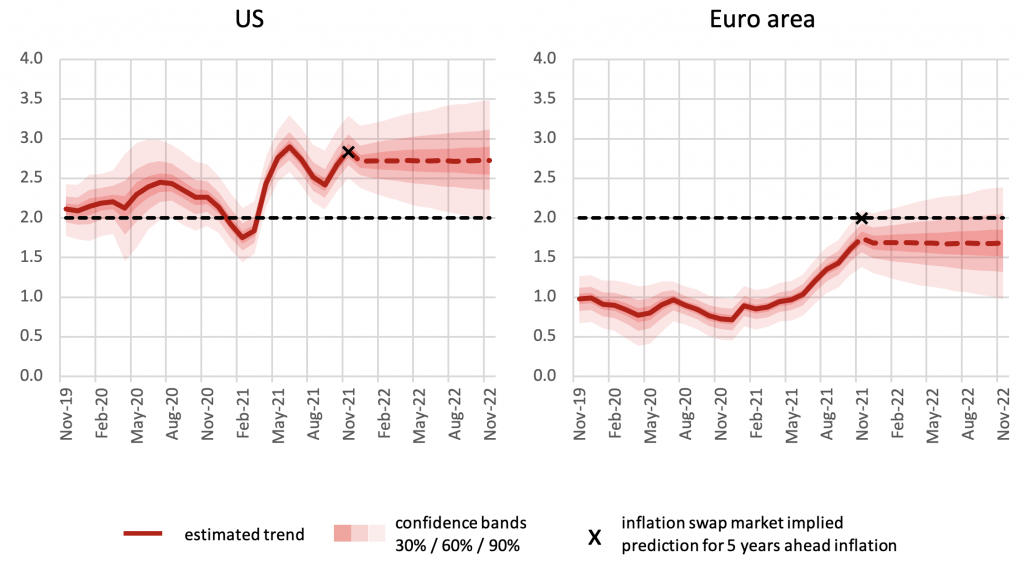

The model defines the trend as the component of inflation that is not due to cyclical components and that is reflected in professionals’ and consumers’ medium-term forecasts of inflation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Trend inflation in the US and euro area (%, monthly, year-on-year, not seasonally adjusted)

Sources: Authors’ computations and Now-Casting Economics Ltd.

The model suggests that, since the onset of the pandemic, the trend component of inflation has risen in both the US and the euro area by a similar amount – approximately 75 basis points. However, in the US, this rise has taken the trend well above the 2% target, whereas in the euro area it is still slightly below the target, at 1.7%.

Interestingly, for the US this is almost identical to the inflation swap market’s implied prediction for five-years-ahead inflation, while in the euro area the level identified for the trend is 25 basis points lower than the swap market’s implied prediction.

This observation gives us some comfort about the ability of our trend estimates to pin down long-term expectations. The difference between the US and the euro area also suggests that the Fed and the ECB can and should respond differently to the inflationary threat – as indeed they are doing. While in the US the inflationary pressure may have pushed the underlying inflation rate above the desired target, in the euro area it seems that inflation is still anchored below the policy target.

Oil Prices and the Cyclical Components

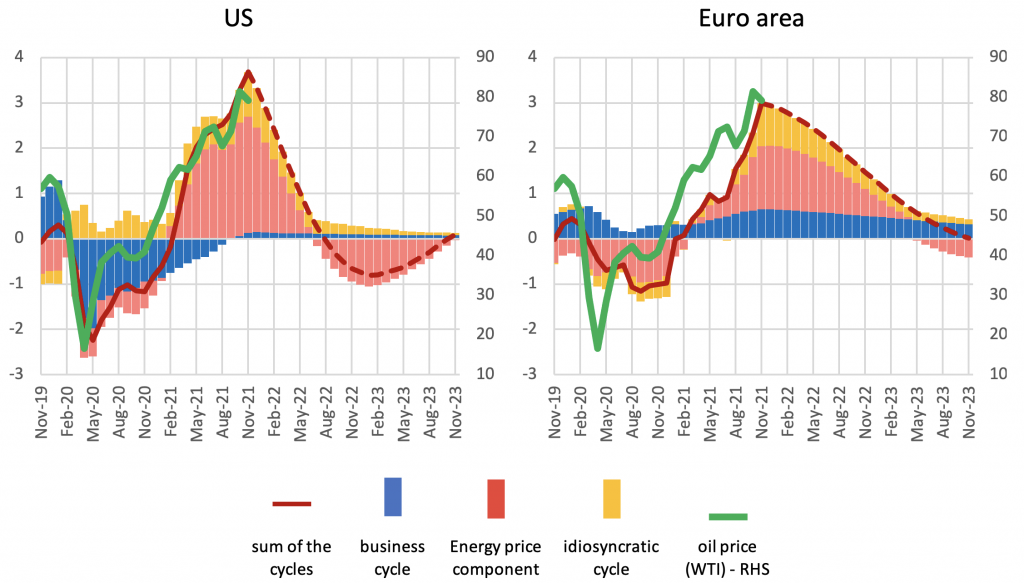

Figure 2 shows the model’s estimate of the recent and future evolution of the cyclical components of inflation: the business cycle (Phillips curve) component, the energy price component, and an idiosyncratic one. The latter may be seen as a measure of what the model cannot explain (and is indeed very small).

Figure 2 Cyclical components of inflation in the US and in the euro area

Note: The chart reports the model’s estimate of the business cycle (blue), i.e., the Phillips curve component; the energy price component (red), and an idiosyncratic component (yellow). The estimates are %, monthly, year-on-year, not seasonally adjusted.

Sources: authors’ computations and Now-Casting Economics Ltd.

The model interprets a large part of the increase in inflation over the past 18 months in both the US and the euro area as a cyclical phenomenon – but it attributes it largely to the rise in energy prices (the red bars). Consequently, the model predicts that inflation will decline in the coming months as the pressure from energy prices turns.

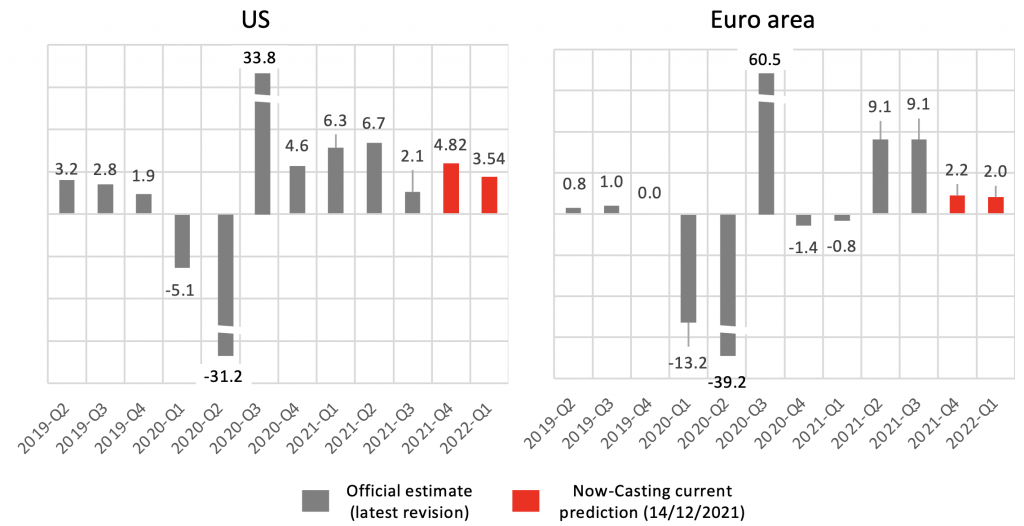

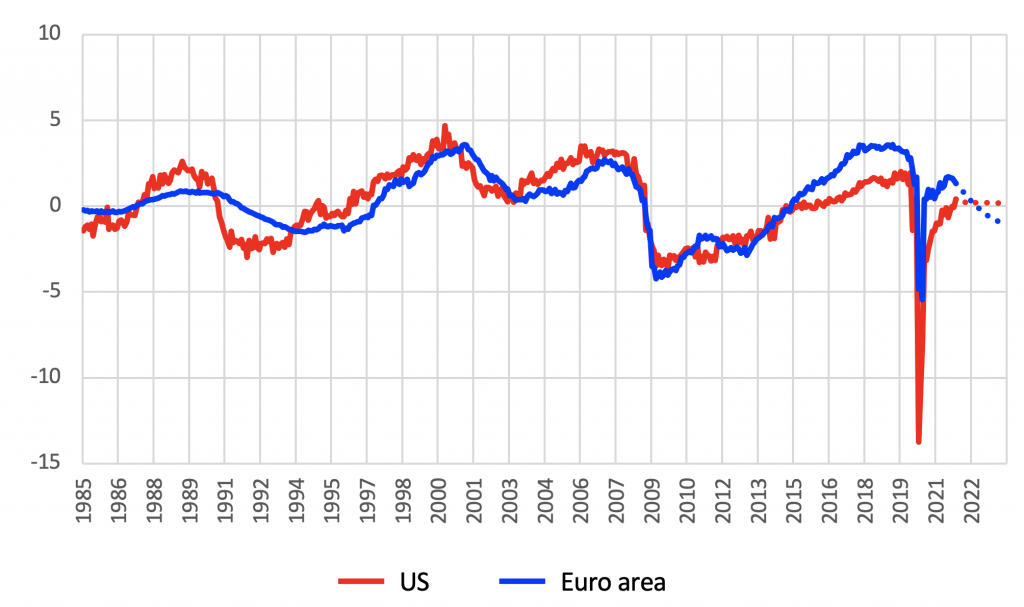

In the US, the energy price component dominates, while the real economy has little impact. By contrast, in the euro area relatively strong growth is seen to be helping to sustain the recent rise in inflation and causing its decline to be slower. This may be surprising, given that real GDP growth in the US has remained relatively strong since the post-pandemic rebound in the second half of 2020, whereas growth has been more volatile in Europe and is now apparently on a weaker path (see Figure 3). However, what matters is growth relative to trend – i.e. the output gap – and the model estimates a closing output gap with the American economy nearly back to its potential growth rate. Conversely, it estimates that the European economy has probably seen a reduction to its potential and hence it may be above trend growth (see Figure 4). Hence the impact of the Phillips curve in the US is negligible whereas in the Euro area it contributes some upward pressure on inflation until at least 2023.

Figure 3 Latest official estimates and current Now-Casting predictions of quarterly GDP growth for the US and euro area (quarter-on-quarter, %, annualized)

Sources: BEA, Eurostat and Now-Casting Economics Ltd.

Figure 4 Model’s estimates of the output gap for the US and euro area (%)

Sources: BEA, Eurostat and Now-Casting Economics Ltd.

In interpreting these results, one must be aware that there is substantial uncertainty over the size and stability of the Phillips curve but also on the estimates of trend growth.

The model view that we have just outlined is driven by two features. First, the estimates of output potential can absorb a persistent component due to shocks in the real economy – akin to hysteresis effects – and, as a consequence, the model tends to attribute less importance to cyclical variations. This is particularly true in the euro area, where the trend is revised downward, and the model is not projecting a return to the pre-pandemic trend over the next year. Second, energy prices enter the Phillips curve via mark-ups and the output gap, as in most macroeconomic models, but also have a purely expectation-driven component which is highly correlated with consumer expectations (this is in line with Coibion and Gorodnichenko 2015).

The model view of the output gap differs from official estimates for both the US and the euro area. In the US, the Congressional Budget sees a stable trend and an output gap which has been negative for more than a decade. In the euro area, again as a consequence of estimating a stable output trend, the European Commission sees a smaller output gap than our model does.

But even remaining agnostic on specific features of the cyclical decomposition, the model, by attributing the bulk of the increases in prices to a cyclical component, and in particular to energy price disturbances, orthogonal to real economic activity, appears to be consistent with past regularities. Notice that the model-based, expectation-driven oil component of the cycle is highly correlated with observed oil prices rescaled (see Figure 2), which suggests that the Phillips curve has had a minor role in cyclical inflation since 2019.

Are Expectations Dis-Anchoring?

A pressing question is whether the model – albeit supported by historical regularities – may be missing a shift in expectations due to the effect of oil prices and the lack of a strong enough policy response.

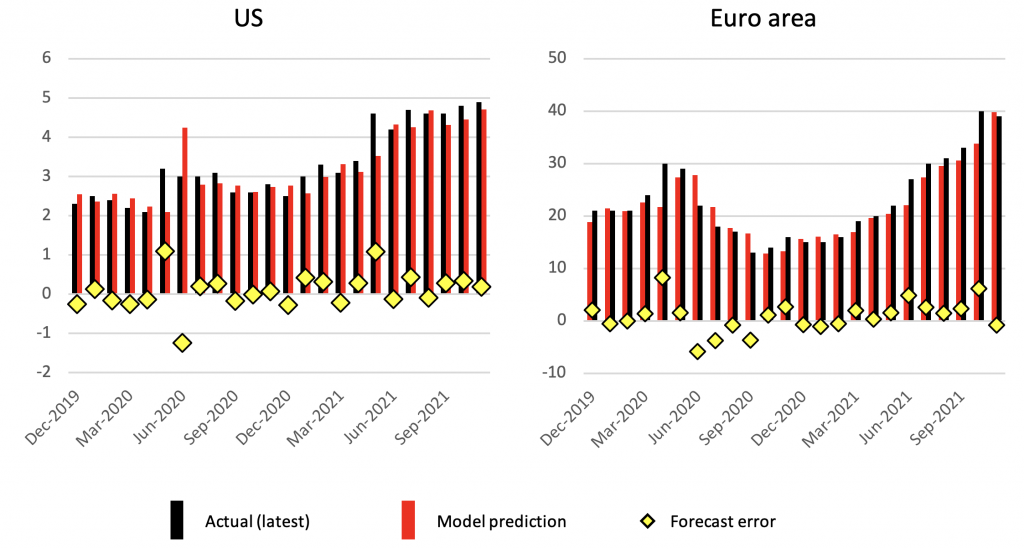

A possible way to address this question is to examine the forecast errors made by the model in forecasting consumer expectations. Systematic negative errors would suggest a ‘bias’ in the model and possibly the drifting of inflation expectations off the target. The fact that the model has not made systematic errors in forecasting consumer inflation expectations (Figure 5) suggests no breakdown of past historical correlations and hence no strong sign of dis-anchoring (beyond that already discussed in relation to the US, where trend inflation is estimated to be 75 basis points above the target).

Figure 5 Model’s forecast errors for consumers’ expectations

Sources: BEA, Eurostat and Now-Casting Economics Ltd.

The Inflation Ahead

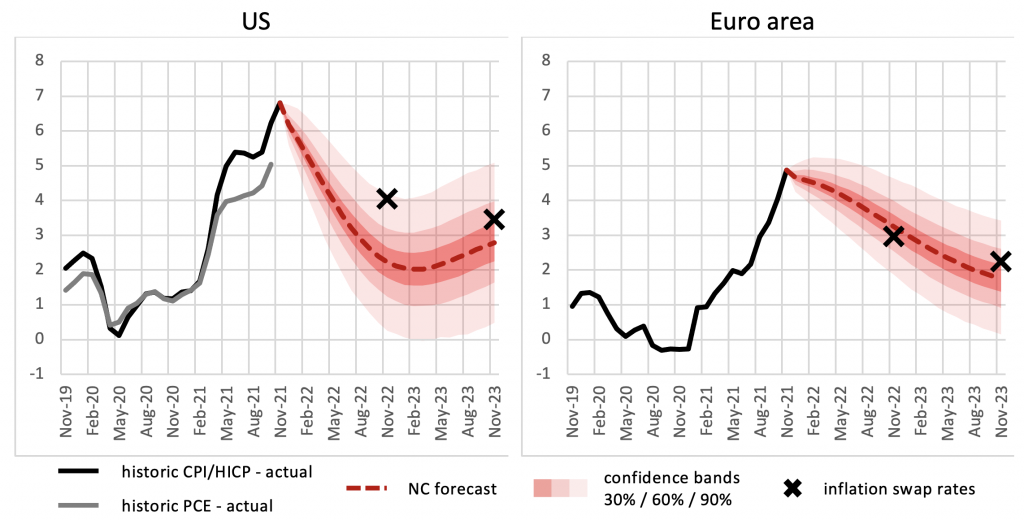

Putting together the trend and the cyclical components, we get the model’s prediction for headline inflation. In both the US and the euro area, the model predicts a cyclically dominated decline in headline inflation over the next 12 months. As we have seen, this is mainly explained by the energy cycle. Due to weaker Phillips curve pressure, the model predicts a faster decline in the US inflation rate than that for the euro area.

Figure 6 The recent path of headline CPI/HICP (monthly, year-on-year %, not seasonally adjusted) for the US and euro area, together with the model’s prediction for their paths over the next 24 months, and comparisons with the inflation swap market’s implied predictions for one- and two-years-ahead inflation.

Note: The historic path of US PCE is also shown for comparison.

Sources: BEA, Eurostat and Now-Casting Economics Ltd.

Our views seem to coincide with those of the market as reflected by inflation swap rates although the swaps predict slightly higher inflation at one year horizon for the US.

Our decomposition helps us to interpret these forecasts. It tells us that both central banks are right when they interpret current inflation as temporary, but that this view should be nuanced in different ways in the US and the euro area. In the US, as we have seen, a small but permanent increase is likely, and this implies a trend inflation rate of 2.75% in the next five years at least (assuming away unforeseeable large permanent shocks in the future).

Interpreting Recent Policy Announcements

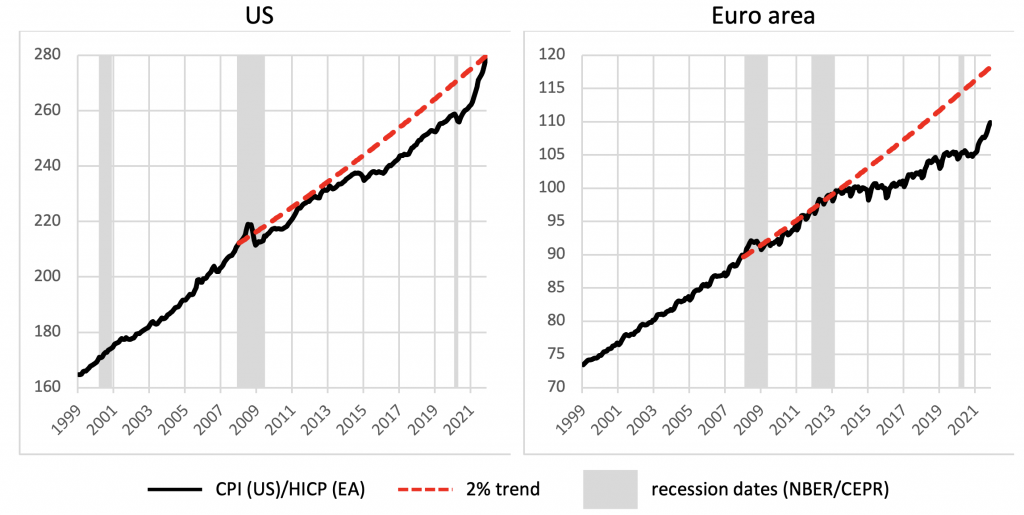

To interpret recent policy announcements, it is useful to compare the actual price level with the price level that we would have observed had inflation been at the 2% target since the recession of 2008 (in Figure 7).

Figure 7 Price levels in the US and in the euro area and the predicted price levels had the inflation target of 2% been hit since 2008

Sources: BEA, Eurostat and authors’ computations.

While in the US, the price level has returned to the level implied by the 2% target, this is not the case in the euro area. This is an additional justification for the different stance by the two central banks.

See original post for references

Personally, I do not experience/perceive inflation as being driven by labor wage increases but by monopolization and profiteering, and IMO we have too few enforced social protections against these. Does the fed ever discuss this? Not to my limited knowledge.

My own monthly energy charges for home are a quarter of the charges for phone/internet/basic tv. In NJ/NY, the price for gas between stations varies by several dollars per gallon and there seems to be enough competition that a consumer can avoid stations that overcharge. It is perhaps a different experience in other states or localities.

Meanwhile, in NJ/NY we have practically no choice about communication services; and that industry seems to me cartel driven. First, when I was in market research, I saw reps from all the major services attend the same strategy and research meetings together at Comcast headquarters in Denver. Second, ten years ago there was a small local cable service in NJ that was named Patriot, with tv svc at $12-15 per month all total; no need for digital cable box, etc. Unfortunately, this company was purchased by Comcast and put out of business; then charges tripled in one month and continued to rise in steady increments.

Maybe I’m just old and cranky, but it seems we’re all being “managed” into corporate profit algorithms for relatively weaker selection. Some people never experienced those early services and others maybe haven’t lived long enough or traveled to acquire alternative perspective. You realize of course that it is part of many marketing plans to disregard the old and/or cranky, so they do not infect the new consumer ranks with negativity. And, 100 variants of Oreo cookies is not consumer choice; that is a monopoly in disguise as category manager, hogging store shelf from true choice options.

Thank you for saying it for me old and cranky.

“…we’re all being “managed” into corporate profit algorithms for relatively weaker selection…” I do think so as well. This perennial little economic protocol (inflation) has such a synthetic texture. Inflation within reason? In order to maintain a smooth and steady ride – so everything needs to be kept under control. And why? The reason has always been to control profits; to ensure them. And so to say that supply inflation or demand inflation is categorically different than “trend” inflation is just not true. They are all of a thing. And our trend is rather worrisome at this point in time for maintaining the illusion that money (profit) has its own value. Which is what this is all about imo. Because we are on a trajectory for… extinction. They reran Attenborough’s “Extinction – the Facts” last nite and the final word of encouragement after facing the dismal truth was that our best hope was massive “investment” to stop the pollution and repair the devastated planet. Well, yes. But splain me just how we get any range of “inflation” out of investments that are unable to extract profits? There are no profits left to extract – from here on in it is all repair work. We need to stop talking about inflation altogether. It is nonsense at this point. Pure nonsense.

Thank you for the illuminating and astute comment. Nothing old and cranky about it.

The big corporations are monopolizing and profiteering while even little companies in select areas are showing how greedy they are, especially in construction because there’s more demand for their services from the wealthy who are spending on home improvement. The cost of concrete work and fencing, etc has doubled, especially for small projects. They’ll bid “what the market will bear”.

You’re not being old or cranky (or at least any crankier than you should be).

I’m a millennial, and I’ve seen multiple instances in my lifetime where price increases were clearly just from a monopoly eating up the alternatives.

That said, this time does appear to be a little different, with inflationary pressure beyond that very real monopoly pricing. I think the tell is that prices are jumping all along the value chain, including for raw materials, suppliers, and transport, possibly at an even higher rate than for consumers.

Yup. And if it’s not monopolies, it’s oligopolies.

I find it interesting how people talk about inflation due to the price of oil, when the spot market price actually hit zero during 2020. Of course gas is more expensive, it was very cheap in 2020.

When we look at this temporary rise in prices people somehow want to talk about the rise in real wages, but nobody talked about the 2% target inflation over the past 20 years was accompanied by stagnant real wages even though the ability to produce increased. If anything the average working person was getting less of the GDP pie – and that wasn’t news.

Meanwhile, the average government deficit since Jan 1, 2020 has been over $1 trillion per year – pretty much 5% of GDP. Neither of the government parties seem bothered by it to any great length.

In the US inflation and debt are only an issue when someone needs a political football to throw around and we all know how long a football play lasts.

When oil was briefly -$43 a barrel in 2020 I bought gas in Cali for $1.57 a gallon and if I had storage capabilities, would’ve gladly bought a few thousand gallons at that price, but settled on 20 gallons worth, a full compliment of the gas tank in my truck. Where would I put 2,000 gallons?

Oil inflation for consumers is a completely different beast than foodstuffs, which can be bought in quantity for future use.

Some foods keep better than others. The only reason for the price of oil to drop that low was Covid, the reason for the price recovering is that much of the economic activity has returned. Besides oil is still down from its highs that happened just before the great recession.

For the people complaining about the cost of gasoline, I don’t understand what they expect the solution to be besides wishful thinking or a worldwide recession to depress demand. Perhaps more massive fiscal and financial subsidies? As opposed to a serious effort on decreasing dependence… which would also deal with the environmental and social costs.

The rising price for oil is due to hard physical limits and constraints. There’s no untapped sweet crude oilfields out there.

Oil reserves are a function of price and crude gets pretty sweet when the price is high enough to upgrade it. I am more bearish on oil in the longer term. Countries are switching over to electric vehicles and they will become even more economical to operate.

I hope you’ll post & discuss Ellen Brown’s latest article on inflation & the Fed. (I found it on Scheerpost). There’s a LOT the Fed can do, a lot Congress can do, a lot the President can do.

Interesting piece. It was all about the Plutocrat Boutique Bank crushing rent-seeking. Arguably, the Plutocrat Bank exists to foster rent-seeking by its member banks and their affiliates, not curb it. No banker who even remotely harbored such subversive sentiments would get within hailing distance of the Board of Governors. Even raising the margin requirements is a bridge too far for these clowns. Interest in and discussions around the Bank of North Dakota, once all the rage, are pretty much in the dustbin.

I hate to say it but Ellen Brown is not reliable on the subject of the Fed. She really does not understand its operations or even much its authority. I have refrained from shredding her pieces because her heart is in the right place.

And as for the Bank of North Dakota, fans of public banks airbrush out that the US was once full of public banks. They were all shuttered ex the Bank of North Dakota because they quickly became cesspools of corruption, bribery, and kickbacks. CalPERS is a paragon of virtue compared to what went on.

Thanks Yves, I was hoping for a topical response from a follower or two. I didn’t expect to hear from you over the holiday, Merry Christmas!

For more than a decade the Fed has (not innocently) watched as our largest banks brutalized the rest of us. It’s no secret these same banks are the principal (& forceful) opposition to new state banks. And, I can’t believe anyone would argue they’re acting for our best interests.

I recently drove cross-country. The drive provides ample evidence our large banks’ investment strategy has failed us miserably. (Personally, I’d like to see =>5% CalPERS & CalSTRS funds moved yesterday.)

EU Natural gas stocks are low for this point in the season. See data at agsi.gie.eu (use the graphs, suggest max scale on time axis)

More recently, as of late September, flows of natural gas into the EU are down about 1TWh/day below typical levels of 4TWh/d. See This Graph [found within a Dec 22 Marketwatch story]. Based on this, pencil in an additional deficit of 90 TWh each quarter, subtracted from the trends you see in the agsi.gie.eu data.

By my unprofessional eyeballing, this extrapolates to EU+Ukraine storage being dead empty just as the heating season ends. Plus or minus weather. No slack whatsoever.

Next year will then see higher volumes to replenish stocks. Seems like a near-certain inflationary impact. The current state of affairs also means EU will max out its LNG import capacity, thus exporting their bid to an already stressed global market.

On the US side, once LNG exports max out, US becomes again (on the margin) isolated from global pricing, as it was prior to the buildout of export capacity. However, reduced oil production means less associated gas coming from the Permian, so that is a factor, although a short-term one. And there are financial issues of course.

“A big reason is many who have real estate and/or stock market gains and face Covid risk in their jobs have decided to pack it in.”

Just thinking about this and the “Santa Rally” in the stock market after a short time of a small trend downward.

Some have claimed insiders and big wigs have been selling all year.

Now this “Santa Rally” – which I look at as Santa handing out bags. So many bags being dumped on investors/traders as well.

I agree. So I won’t get started. But I will get started on something else.

I am especially curious why you think inflation can’t be tamed by interest rates and yet growth can. Why would growth be reduced by interest rates yet demand in most of the areas you list not be tamed?

Now I don’t want to resort to economics 101 but I see no other approach. Prices are rising because of excessive demand is the mirror image statement to prices are rising because of excessive supply. Though depending on demand/supply elasticities you could choose to attribute more to column S than column D, it is still an inescapable truth.

I would also agree (if that was the implied point) that interest rates are a fairly blunt and inaccurate instrument to apply. However QE and interest rates are the suitable instruments to broad based inflation. Some of the key drivers automobile sales, a huge housing boom are discretionary purchases that are HEAVILY influenced by interest rates.

I must say I’m heavily in Wolf Richter and camp here. Also I find it inescapable to not conclude that “Inflation is Always and Everywhere a Monetary Phenomenon”. Sure there might be other causes like a bad harvest or a chip shortage or other reductions in gross output. But that just reinforces the point, if the same wages are chasing fewer good what do we expect to happen?

The question is how long are supply issues going to last. Unless they are extremely short lived (transitory) then we need to reduce (defer) demand. And there is one very direct tool that encourages the intertemporal transfer of demand today to demand tomorrow. Short term interest rates. In fact it is the most appropriate and also the natural tool.

Increasing interest rates will reduce spending via the wealth effect. Its strongest impact is via real estate values. The wealth effect of falling stock prices is considerably exaggerated.

The Fed also thinks that increasing interest rates will lower demand and growth (via negative wealth effect and making borrowing more costly), that’s the channel that they think will also reduce inflation.

The inflation is due to real economy issues that are not or not much related to total demand, such as workers staying at home despite plenty of jobs and higher wages. We had stagflation before. The Fed is out to create that.

I agree that the wealth affect will play is active. Though I would counter that there are bigger wealth effects from high stock prices and high house prices.

Anyway. I appreciate your work Yves. In fact I’ve been eagerly awaiting your comments on the current inflation environment. I was a little surprised that it was significantly different from my outlook, but I can’t expect agreement on everything. :-)

The RBA here in Australia has been even more dovish than the FED! I’m certainly positioning myself financially for low rates for longer.

Sorry, there are many many many empirical studies on the wealth effect. It’s about 3x as strong for real estate as stocks. And what is driving inflation in Oz may be markedly different than the US. For instance, are businesses that hire hourly workers having a difficult time with staffing on a widespread basis?

Sorry I actually misread your previous post. I am in complete agreement with you regarding the wealth effect of real estate and stocks. Where we disagree is that I think spending should be curtailed to reduce inflation. Hence advocating increasing interest rates.

OZ is fairly different from the US in this instance. We haven’t had large reductions in worker participation or gross output. Inflation pressures are there but not to the same extent as the US. One big difference is Australia’s trade balance has been moving strongly positive while the US strongly negative.

Most folks around here could explain to you why Econ 101 is wrong. Yves literally wrote a book about it.

Personally, as an economist working in business, I find that inflation is almost always NOT a monetary phenomenon. What we are seeing now is largely driven by supply chain issues that are limiting supplies and increases costs. Business has been passing these on to customers as well as tacking on additional margins for themselves. Over the summer, we were seeing businesses reporting record profit margins. That’s not all from cutting costs. Currently, wages haven’t kept up as much as prices although we are beginning to see some of that as employers are struggling to fill low-paying positions. None of those things is caused by an increase in the money supply.

Furthermore, if you read some more about the history of depressions in the US, you’ll find out the bigger issue was typically that the money supply couldn’t expand fast enough since it was pegged to gold.

“Think about what inflation is…. its prices going up requiring more money to buy things… We need to get that extra money in the hands of the people that need it most!”

Joe Biden, impromptu presser Dec 22nd 2021.

“…Inflation is caused by the fall in the external value of the mark against foreign currencies and that the role of the Reichsbank is to print sufficient money to sustain the higher price levels driven by the fall in the exchange rate and rising demand for money within the German economy…”

Rudy Havenstein , May. 1923.

The problem with inflation is that no one can really define it in a complex economy and as a result there are so many types of inflations to suit every economic dogma out there.

What most people think of inflation is their money buying less and less. From that angle we have ben having consistent inflation since the great depression.

I think Friedman gets it and he was right and will be proven right again. “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

Friedman and von Hayek have already been proved wrong. MV=PQ may be correct but V and Q are not constants. So M does not equal P.

If you read the work of Friedman and check his math on MV=PQ he says clearly that the relationship holds only if V is constant which was assumed to be so at that time.

Despite the fact that V is empirically demonstrated NOT to be a constant, Friedman’s zombie ideas still shuffle across the public narrative and policy space. It’s ridiculous.

Milton didn’t care as long as his multi-millionaires had money. He is one of those who knew the price of everything but the value of nothing.

Thanks for you comments aj. I too agree that there is much in Econ 101 that is wrong. This wrongness is what drove me to post grad study in economics and drove me to this blog almost 15 years ago. (It also drove me away from my short career in economics and finance).

You have a whole litany of reasons why prices are rising, all of them are valid but none of the seem to be looking at the other side of the coin which is demand. ANY time somebody says prices are too high because of supply issues somebody can equally say prices are too high because the demand is too high for the current level of supply.

This argument is inescapable even for largely inelastic goods. If a harvest fails and food prices triple the primary supply cause is obvious. However the reason why prices increase 3x rather than 10x is that ultimately consumers cut back.

If it isn’t a monetary phenomenon then what sort of phenomenon is it. We are literally talking about the exchange rate of money and goods and services. To say that it is intricately linked with the demand/supply of money and the demand/supply of good & services is a truism.

In my eyes the biggest conundrum is defining and measuring what exactly IS the money supply is the more difficult problem.

From jim truti’s post:

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

Or in this case a decrease in output that hasn’t had a corresponding decrease in the ‘quantity’ of money.

Since inflation deals with prices and we use money to price things, then yes in that sense inflation has to be a monetary phenomenon by definition. What I was trying to say is that I don’t think increases in the money supply have near the impact as do supply chain issues and greedy wall street execs. like a few people have pointed out, the equation is simple mv=pq. But you can’t assume that any one of those things stays constant. In fact, if business are raising p and there is demand for q, then you need the money supply to increase in order for the market to clear. this is the issue I brought up early that used to cause depressions and bank runs

Thanks for you comments aj. I too agree that there is much in Econ 101 that is wrong. This wrongness is what drove me to post grad study in economics and drove me to this blog almost 15 years ago. (It also drove me away from my short career in economics and finance).

You have a whole litany of reasons why prices are rising, all of them are valid but none of the seem to be looking at the other side of the coin which is demand. ANY time somebody says prices are too high because of supply issues somebody can equally say prices are too high because the demand is too high for the current level of supply.

This argument is inescapable even for largely inelastic goods. If a harvest fails and food prices triple the primary supply cause is obvious. However the reason why prices increase 3x rather than 10x is that ultimately consumers cut back.

“I find that inflation is almost always NOT a monetary phenomenon.”

If it isn’t a monetary phenomenon then what sort of phenomenon is it. We are literally talking about the exchange rate of money and goods and services. To say that it is intricately linked with the demand/supply of money and the demand/supply of good & services is a truism.

In my eyes the biggest conundrum is defining and measuring what exactly IS the money supply is the more difficult problem.

From jim truti’s post:

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

Or in this case a decrease in output that hasn’t had a corresponding decrease in the ‘quantity’ of money.

“Or by a decrease in output that hasn’t had a corresponding decrease in the ‘quantity’ of money.” Raising the argument that progress (improvement) is deflationary because it is ever more efficient. But in a world that needs to reclaim nature and stop massive extraction and ever-expanding industrial production which more or less increases the momentum of the economy in order to merely stay in place (profit-wise) to keep from imploding, then the whole idea of inflation is obvious. And revealing, in that we can see, to our horror, that inflation IS the economy. If we were true to our ideals (an ever better world), we’d can the whole inflationary hallucination and create an economy that was steady and sustainable and the word “inflation” would only apply to bicycle tires.

I’m no economist, I struggle to follow the many great comments on inflation here.

What puzzles me today is where is the great debt debate going – because isnt that an even bigger issue

If i was the Fed, I’d be quite happy to see a bit of imported inflation, with rapidly changing descriptions and vigorous discussions of its nature, plus a bit of raised interest rates to come later as my inevitable response.

That acceptance in all my committees would help me as the Fed to inflate away part of the global debt overhang.

It would also effect another huge transfer of wealth, but if I was the Fed then perhaps that is just fine by me.

I’m not the Fed, I am not even managing the cookie jar, so I’m very sure I’m wrong, but I’m still struggling to see where the debt mountains fit into all this calculating and defining about inflation

it costs a lot of money and fossil fuels to stock your shelves with foreign made products. the only ones who make out under free trade are the rich!

The discussion about inflation shouldn’t be technical about its workings intricacies and nature but rather a moral one first.

Imagine discussing how to rob your neighbor and instead of worrying whether its wright or wrong to do it, we spent countless hours discussing the technicalities of how to get away with it.

For the average American, money represents the hours of his life that he spent earning it.

That’s the basic principle here.

It represents concentrated life, all the things you want to have and do for yourself, and provide for others in the future.

At its core, money is a moral contract between the government and the people, the raw material it is made of is public trust.

When the Fed and the government deliberately destroys the value of money, they’re destroying part of your life.

As they deliberately engage in channeling financial rewards to big government, big business and investors at the expense of small savers, retirees and blue collar workers, they are undermining the basic founding values this nation is built on: equality of treatment for all.

Too many technical terms used by economists for what is really just an economic dependence on blowing bubbles to make the wealthy more wealthy, then dump and do it all over again and the age old reliance on creating a desperate populace that will provide cheap or free labor.

They think describing it using mathematical formulas makes it sound reasonable.

Money cannot be a moral contract. It is just numbers and perfectly amoral.

Dollars are no more moral than inches.

And yet inches not decreasing in value or size year by year.

Where a state take monopoly control of the currency of trade then I don’t see how it is a difficult argument to make that it has a responsibility (ethical, morally, or otherwise) to ensure that the currency of trade is suitable for purpose. Suitable for purpose is very broad but certainly one of my definitions is not unduly volatile. Preferably mostly stable.

It’s good to see data and discussion around both US and Euro trends. Inflation may be “always and everywhere” a monetary phenomenon, but its effects and perception have a large psychological component, and are therefore subject to political suasion. Confidence is always a factor.

Anyone making hay in the US by attributing inflation to presidential / party politics has to deliberately ignore the fact that the US and Europe are on generally similar tracks. That is, until the FED / ECB differences emerge. We Shall See.

Once again, you can’t fix stupid.

Forty years after the Volcker Fed completely misdiagnosed oil-shock inflation and engaged in disastrous monetary policy, it seems Powell is indicating he will make the same mistake. Monetary policy can’t fix what fiscal policy and geo-political detente can. Interest rates have no control over shipping logistics affected by COVID, or the ability of various entities along the supply chain to increase prices. Again, the wonderful article shared here about Jani The Giraffe (via Time) laid this out quite well in layperson’s terms. I came across this from Abba Lerner recently (vi JSTOR) – the title page preview is sufficient. He articulates the difference between buyer’s inflation (a.k.a demand pull) and seller’s inflation (a.k.a cost push). Shock inflation, reminiscent of the 70’s oil crisis and what we have now during the COVID pandemic, is cost-push/seller’s inflation. Note well what Lerner says will happen if you try to treat buyer’s and seller’s inflation with the same policy (raising interest rates, taxes):

“… if restrictive monetary or fiscal policy is used against sellers’ inflation, spending is reduced when it is not excessive, so that we get a deficiency of demand, depression and unemployment. The inflation will continue, however, unless the induced depression is severe enough to destroy the power of sellers to raise their prices.“

It’s the power of sellers to raise prices, stupid.

And most pertinently, the power of energy producers, more than anything else. A year ago, WTI futures went negative. Today, all the MSM parrots just say “energy prices are rising” as if it’s written in stone. Biden telegraphed releasing stock from the US strategic reserves, but like everything else his administration has done, it was merely a gesture – something like a day or two’s worth of supply. Meaningless. I guess the Saudi’s buy enough military equipment to warrant keeping prices high. Pity the US is too busy trying to coup Venezuela instead of having them as an ally with the world’s largest proven reserves. Love to remember that time Hugo Chavez sent free heating oil to the freezing poor in the South Bronx (via Reuters). Oh well … imperialism FTW.

Two follow-up comments. The first: if you read the tea leaves from MSM and Econ/Finance PMC types, you’ll see “Tall Paul” Volcker praised as the man who tamed inflation. From Volcker’s NY Times obituary:

Mr. Volcker’s message was that the Fed was declaring war on inflation. “The basic message we tried to convey was simplicity itself,” he said later. “We meant to slay the inflationary dragon.”

To underscore the Fed’s determination, Mr. Volcker announced a significant change in the conduct of monetary policy. Historically, the Fed had aimed to control interest rates — the price of money. Under the new policy, he said that the Fed would instead aim to control the supply of money. Limiting the money supply would cause interest rates to rise, but the Fed would no longer aim for a specific increase. The central bank would determine how much money was available; markets would set the price.

The change was part of a broader shift in economic policymaking toward a greater reliance on financial markets. It marked the end of the postwar era in which disciples of the British economist John Maynard Keynes had argued that governments could deftly manage economic conditions, including interest rates.

An immediate result was that markets pushed interest rates a lot higher than Mr. Volcker had anticipated. The prime rate, which banks charge their most creditworthy customers, nearly doubled by Election Day 1980, peaking at 21.5 percent. Farmers on tractors circled the Fed’s headquarters. Auto dealers sent the keys to cars they could not sell. “Dear Mr. Volcker,” one builder scrawled on a wooden block with a knothole. “I am beginning to feel as useless as this knothole. Where will our children live?”

Mr. Volcker later confessed to doubts, telling an interviewer in 2016 that he had worn a path into his office carpet while waiting for inflation to surrender. And, early on, he blinked: After tipping the economy into recession in early 1980, the Fed briefly took its foot off the brakes.

But when inflation showed signs of accelerating, the foot slammed back down, and a deeper recession began. Thereafter, Mr. Volcker was obdurate, insisting that the pain was necessary and ultimately worthwhile.

Asked by a reporter how much unemployment he was willing to accept, Mr. Volcker responded, “My basic philosophy is over time we have no choice but to deal with this inflationary situation.”

In other words, another Lord Farquaad – the pain of the masses was a sacrifice Volcker was willing to make.

The second: On the occasion of Margaret Thatcher’s demise, Warren Mosler, one of the primary architects of #MMT penned this at New Economic Perspectives: And the Last Shall Be First – It Was the Peanut Farmer, Not the Tall Guy or the Iron Lady

Excerpt:

But in the early 1970′s demand for crude exceeded the US’s capacity to produce it, and Saudi Arabia became the swing producer, replacing the Texas Railroad commission as price setter. And, of course, price stability wasn’t their prime objective, as they hiked price first to about $10 by maybe 1975, which caused a near panic globally, then after a too brief pause they hiked to $20, and finally $40 by maybe 1980.

With oil part of the cost structure, the consumer price index, aka ‘inflation’, soared to double digits by the late 70′s. Headline Keynesian proposals were largely the likes of price and wage controls, which Nixon actually tried for a while. But it turned out the voters preferred inflation to their government telling them what they could earn (wage controls on organized labor and others) and what they could charge. Arthur Burns had the Fed funds rate up to maybe 6%. Miller took over and quickly fell out of favor, followed by tall Paul in maybe 1979 who put on what might be the largest display of gross ignorance of monetary operations with his borrowed reserve targeting policy. However, a year or so after the price of oil broke as did inflation giving tall Paul the spin of being the man who courageously broke inflation. Overlooked was that President Jimmy Carter had allowed the deregulation of natural gas in 1978, triggering a massive increase in supply, with our electric utilities shifting from oil to nat gas, and OPEC desperately cutting production by maybe 15 million barrels/day in what turned out to be an unsuccessful effort to hold price above $30, as the supply shock was too large for them and they drowned in the flood of no longer needed oil, with prices falling to maybe the $10 range where they stayed for almost 20 years, until climbing demand again put the Saudis in the catbird seat. Meanwhile, Greenspan got credit for that goldilocks period that again was the product of stable oil prices, not the Fed (at least in my story.)

In other words, what really fixed inflation/stagflation was not Fed policy, but shift to natural gas from oil which nullified the power to oil producers/sellers to increase prices.

Volker was a phony but he had connections with the PTB and they gave him credit for taming inflation, which he didn’t.

I wish we had “the everything audit” which evaluated every resource on the planet. In real time. We’d be able to calculate our chances for achieving a better life by using fact-based data – not just cherry-picked info and actuarial tables and money. That would be a big big study. And applying the values of everything, of all our resources – even the ones we no longer use (like stones in the stone age) to economies would be more art than science. But there’s still lots of art lurking in science. So why not? It’s a better way to get outside our thought-rat-race; better that always walking into the patio door.

again, it costs a lot of money and fossil fuels to stock your shelves with foreign made products. the only ones who make out under free trade are the rich!

interest rates will not touch this inflation, its self inflicted from free trade.

volker could have cared less about inflation, same with alfred Khan, the great con. what they were after is what nafta joe biden is after, to take away labors chance for a better standard of living.

Yup. Volker and Greenspan’s #1 priority was breaking labour power and keeping it broken.

How could they have been oblivious to the fact that they were actually breaking demand and that demand was what kept the whole tent up. I’m pretty sure our corporations were looking at China as a demand bonanza – but not at the balanced cost of labor in the US. Our government and corporations should pay all the freight on that misadventure; for destroying labor and industry in the US without so much as a safety net; no alternatives except entrenched poverty and drug addiction. Even the drug addiction was for corporate profits somewhere in the chain. We need laws against this inhuman behavior. Where is the free speech?

all my life i have heard out of the rich and powerful, they have the money, just hold them by their feet and shake hard.

the free trading dim wits said just move, go get another job, learn how to code.

i know of no free trader with the where with all to understand that demand for goods and services is wage driven.

those dim wits actually believed milton friedman and hayek. those dim wits are nafta democrats.

the democratic party became nafta democrats under bill clinton. and they still hold sway today.

remember, as nafta billy clinton committed treason by ramming free trade down our throats, at the same time he almost completely wiped away the new deal, including the safety net.

he almost got social security, and he did get medicare, he made massive cuts, and created medicare advantage.

so in reality you have to think like a sociopathic imbecile, and understand, yes they believed that crap.!

nafta joe biden is seething at the bit to institute austerity.

Even if everything Yves said is correct, it is still wrong for Fed to set rates below inflation. It means those who can actually borrow at those rates – which is ultra rich gamblers like people running WeWork or Uber – continue to get giant subsidies while the common folk keep getting their savings stolen.

So it looks to me like more of wealth transfer from poor to rich.

If rates are above the inflation rates, then no free money for anyone and everyone is forced to show they are doing something productive and not just engaging in more creative financial swindling, which is what all growth has been ever since Fed started to give away free money.

I’m leaning towards this idea some also, and IIUC, it doesn’t actually contradict what Yves is saying.

Now that we’re already here, raising rates won’t do anything to fix supply-push inflation, unless you push it far enough to cause a major recession and destroy demand. I agree that’s not really a fix, in the same sense that killing a patient doesn’t count as curing their illness.

But in the long-run, I think it’s hard to argue that all the easy-money since the Great Recession didn’t unleash a Cantillon Effect from hell, resulting in a lot of waste on speculation, arbitrage, and vanity projects. In a healthy society, low rates probably could stimulate even more investment that actually improves the average person’s quality of life. In America today though, it seems like the lower interest rates go, the more finance (and resource allocation) decouples from the real economy.

here is a different take:

https://johnhcochrane.blogspot.com/2021/12/the-ghost-of-christmas-inflation.html

I got around to reading it, and while I agree with a couple of his basic points (e.g. you can’t have inflation without demand), I mostly disagree.

What’s interesting is that IIUC he also thinks just raising interest rates won’t magically stop this inflation, at least not directly. He also seems to agree causing a recession would be the one clear way to stop it, though he emphasizes balancing the government budget, not the consequences of slashing deficit spending. It seems the real difference is simply that he feels the “cure” of austerity isn’t worse than the disease of inflation.

I won’t lie, I got really excited when I read this at the end…

… but then had a sad when he went on to describe Reaganomics instead of actual industrial policy.

To help me decide if I agree with Yves on the sources of the labor shortage, I need to know more about the recent shifts in the age, social class, Covid vaccination status, real estate ownership rates and income levels of those leaving employment. Anyone out there have any insights into those numbers?

Also, the long term and now radical divergence between the BLS household survey numbers and the employer survey numbers suggests that my personal observations that many more are now informally employed is part of the issue.

Then there is supply side. Frackers lost bags of money. For them to continue to drill and frack the price of oil in the US must go up… but how much? I hear long-term $75bbl is enough. And if they don’t expect that number, are we going to see production slowly decline in the near future?

And the $1 trillion/year to cover the expanding debt; where does this excess liquidity fit into the equation since here in Austin a fair amount of it returns as flight capital converted into real estate and real estate price inflation. Is the US the new Vancouver?

My economically informed friends from my DC days say inflation is “transitory, like the 1970s in that it is led by oil prices with a market correction of 10-15% coming in the next six months”.

I have more questions than answers. But some of the readers here may have information to contribute based on a deeper knowledge of the statistics than I possess.

Warren Mosler argues manipulated bank rate is in itself inherently inflationary. See section on Inflation:-

https://gimms.org.uk/2021/12/19/conversation-with-warren-mosler/

Yes. I remember a clip, a chalkboard demo, (not by Mosler – but a likeminded person) showing how a 2% interest rate (not an outrageous rate to most economists) over time compounded in pockets of wealth until it reached a critical mass trajectory and just exponentiated right up to the Celestial. Because there was nothing in the economy to balance it out. Showing how a mere 2% interest rate could push everything completely out of balance in fairly short order. Also very Picketty.