By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

“… forced to learn a difficult trade in a driving hurry…” –Patrick O’Brian, Post Captain

This post is a companion piece to an earlier post, “The Romance of Shipping Containers,” where I was quite taken with how shipping containers “embodied two subjects I really enjoy: Transportation, and international standards” (I’m terrific at parties). I was also taken with the modularity of stacking up (more or less) identical containers. I did not, however, consider the material realities — the physicality — of moving shipping containers from Port A to Port B, whether oceanic or human, which I hope to do now, while still digging into some standards. (The shipping industry is gloriously complex and has a long history, so I’m going to give readers plenty of opportunities to remedy any errors or omissions.)

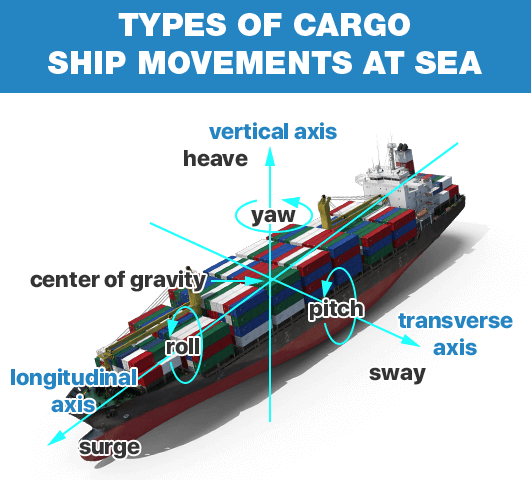

A ship at sea moves — or rather, is moved, by the ocean — in six degrees of motion: heave, sway, surge, roll, pitch and yaw. Here is a handy diagram, from Freight Forwarder:

You can see at once that if containers were simply stacked up like children’s blocks, the materiality of the sea would cause them to slide off the deck in short order, never mind what a storm might do. Hence, some method must be used to secure the containers. This method is called “container lashing,” or “lashing.” From Marine Insight:

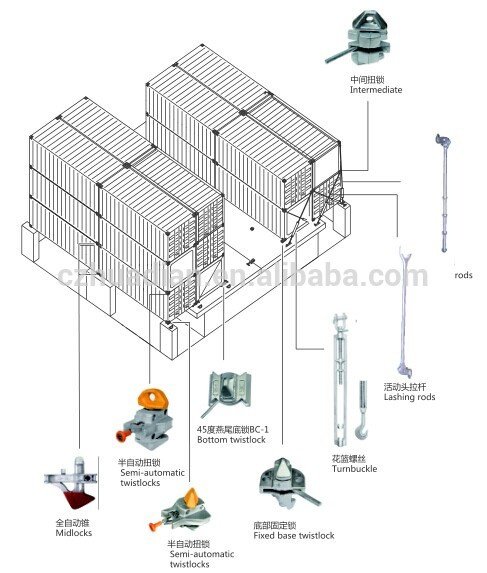

When a container is loaded over ships, it is secured to the ship’s structure and to the container placed below it by means of lashing rods, turnbuckles, twist-locks etc. This prevents the containers from moving from their places or falling off into the sea during rough weather or heavy winds.

Not just lashing rods, but also wires, chains, ropes, and straps. There is, apparently, a myriad of proprietary lashing systems, necessarily compatible with the standardized fittings of the containers, but otherwise incompatible.. Here is a diagram of one rod system:

(Presumably sold on Ali Baba, hence the watermark).

Alert reader Charlie Sheldon described working with a rod lashing system:

a huge part of preparing a ship for sailing is “lashing” which is done by longshoremen when loading the containers and then checked by the ship’s deck crew once underway. Lashing refers to these 12 to 20 foot long one inch diameter rods, with turnbuckles threaded at each end with shackles, which are fastened to the corners of containers and then placed on the ships walkways between stacks of containers, and tightened using big rods turning the tunrbuckle, such that these long rods are drawn as tight as possible to attach the stacks of containers not only to each other but to the ship, too. Between each stack of containers on a ship is a space, about 6-7 feet wide (?) which yu can see when a ship crosses in front of you and you see it side-on, and in that space, rising three or four levels about the main deck, is a gantry platform, with a level at each container level, and railings, accessed by ladders at each end of the gantry (ie at each side of the ship) and this is the thing those lashings are fastened to, and tightened from. It is hard work, but essential because if the weather gets bad those stacks will move and sway, and, unless held down, will come loose, and often they come loose anyway if the weather is really bad. When I sailed we ran the east coast of the US (New York, Charleston, Savannah, Norfolk and then we crossed the Atlantic through the Straits of Gibraltar to the Suez Canal on our way to Singapore) and when we left Norfolk we’d turn to to check all the lashings and make sure they were tight. This took two or three days, actually. Then we’d check everything again before we reached Gibraltar, and it was astounding how much those lashings would go slack because of the ship’s motion. I don’t know if you can call this work highly skilled, but it is hard physically and tough to do properly, and that gear is heavy and dangerous. If a section of one of those lashings, say if the turnbuckle and shackle are unthreaded from the rod, that turnbuckle section and shackle alone weighs 30 pounds, and if it drops or falls and your hand is in the way youl’d lose your hand. I almost lost mine, three times.

(This is the physicality I said I would center.) Here’s some detail on the safety precautions that should be taken by workers doing container lashing. From Marine Insight:

- Wear all the required Personal protective equipment (PPE) such as a reflective vest, steel toe shoes, hard helmet, gloves etc.

- Stretch and warm up your muscles prior to working as it is a strenuous physical job.

It’s like the workers are professional athletes…

Try using a back support belt and always use your knee to lift. Be cautious while walking around the ship as the ship structure can be a tripping hazard. Be careful from slip, trip and fall while boarding or leaving ship from gangway with carrying loads Do not walk under suspended load i.e. gantry, hanging container etc. Work platforms, railings, steps, and catwalks must be inspected prior to the starting of operations. All manhole cover or booby hatches to be closed while lashing. Be careful while walking over the rods and twist locks while working. Always keep the lashing equipment in their assigned place or side of the walking path. Understand the plan and order of lashing and unlashing. The reefer containers require extra attention and coordination for plugging and unplugging when loading or unloading is carried out. Beware of trip hazard due to reefer container power cord. Do not touch any electrical equipment or power chord until it is instructed that it is safe to work on. All the lashing and other materials must be removed and secured from the top of the hatch cover prior to the removal of the same. Be careful of fall hazards when lashing outside containers on the hatch cover or pedestal. Fall arrester or safety harness must be used by workers when operating aloft. Always be at a safe distance from co-workers during lashing or unlashing containers as the long rods can be hazardous if not handled properly. It is a normal practice not to lash or unlash any closer than at least 3 containers widths away from another co-worker. Always work in pairs when handling rods and turnbuckles. Always walk the bars up, slide them down and control the rods at all time. Do not leave or throw the rod or other equipment until you are sure that it is safe to do so and no one is around the vicinity. Do not lose a turnbuckle and leave the rods hanging. When securing a rod, the turnbuckle must be tightened right away. Always report defective lashing gear, defective ship’s railing, or any other inadequate structure or system involved in the operation to the concerned person or ship’s staff.

Less than 0.001% of the estimated 226 million containers carried every year are lost overboard each year. Nevertheless, when containers are lost, carriers are unhappy, and anxious to share their unhappiness with others. Here’s one example of an accident caused by bad lashing, from Container News in 2020:

According to the MAIB accident report the loss of 42 containers and the damage to 34 others, on the 7,024TEU Evergreen container ship, Ever Smart, …

Boy, those Evergreen guys… They have all the luck, don’t they?

…most likely occurred during a period of heavy pitching and hull vibration in the early morning of 30 October 2017 [Pesky ocean! –lambert].

The United Kingdom government agency said that a combination of factors resulted in a loss of integrity for the whole deck cargo bay; in particular, the boxes were not stowed or secured in accordance with the cargo securing manual. In addition, the container lashings might not have been secured correctly, said the accident report.

“Cargo securing manual,” you say? That brings me to the world of international standards.

The Cargo Securing Manual (CSM)

Here is functional definition of a Cargo Securing Manual, from Wartsila:

[Cargo Securing Manual (CSM)] required on all types of ships engaged in the carriage of all cargoes other than solid and liquid bulk cargoes. Cargo units, including containers, shall be loaded, stowed and secured throughout the voyage in accordance with Cargo Securing Manual approved by the Administration.

And here is a technical documentation house‘s descrlption of the institutions involved, and its deliverables:

A cargo-securing manual is a document that must be certified by classification societies….

We’ll get to classification societies next.

….and is required to be equipped on all oceangoing vessels carrying cargo (containerships, pure car carriers, conventional cargo ships, refrigerated-cargo vessels, steel-product carriers, timber or log carriers, box-shaped ships) except bulk carriers. We at MTI offer our customers a service for producing cargo-securing manuals for newly built ships by taking advantage of our experience and know-how in marine transportation technologies for various types of cargoes. The manual we prepare satisfies requirements by the NK, LRS, DNV, and ABS classification societies. A manual for other classification societies can be prepared upon request. Send us a drawing of the ship, and we can provide a full range of support from the production of the manual to the acquisition of the necessary certificate from the classification society.

Notably, each ship has its own CSM, unique to it (quite different from the modularity of containers; the ships are not modular at all). Note that the CSM defines the lashing pattern for the ship — i.e., the location, sizes, and weights of the containers, and their arrangement such that the stack does not destabilize — but not the actual lashings involved (which, you will recall, are proprietary). From Ships Business:

The Cargo Securing Manual issued on ship’s delivery does not detail the minimum quantity of portable securing/lashing devices that should exist onboard. There is no minimum industry quantity of lashing stipulated nor guidance on the required percentage of spares. The minimum quantity of portable securing/lashing devices is defined by the commercial needs of the ship and therefore, the minimum quantity of portable securing/lashing devices is that required to secure the intended stow of containers following the lashing pattern given in the approved CSM.

The CSM requires that there be a list of lashing devices, but doesn’t specify what’s on the list. You can see a lot depends on the tacit knowledge of the workers actually doing the lashing, and their commitment to doing it properly. The wording of a CSM “Model Manual” (presumably a template to be modified ship-by-ship) from Det Norske Veritas underlines this point:

2.3 General Information

1 The guidance given herein should by no means rule out the principles of good seamanship, neither can they replace experience in stowage and securing practice.

Professional Mariner makes the same point in a different way:

Cargo stowage inside containers causes problems, as a container stack is only as strong as its weakest container…. [T]he container securing manual (CSM) must be followed accurately, and further stowage guidelines should be sought for problematic cargoes. One of the challenges is that container carriers largely depend on shippers, freight forwarders or their subcontractors [i.e, the workers –lambert] to pack and secure cargoes adequately. Errors are inevitable.

And from one of the insurance companies that will end up paying for the “errors,” Steamship Mutual, on one particular sort of error, overweight containers:

It is, of course, good ship’s practice not to allow loading operations to commence without receipt of a proposed stowage plan or, at least, a stowage plan for those containers about to be worked. This plan must then be checked against the ship’s computer loading/lashing programme and/or CSM to ensure that permissible limits are not exceeded…. However, wrongly declared container weights are difficult if not impossible to identify. The only guard is vigilance on the part of the ship’s crew in terms of adequate supervision of loading. If feasible, loaded containers should be cross-checked against the stowage plan and computer programmes and the CSM used to ensure that the ship’s requirements are being complied with.

And now to the standards bodies that require the necessary but not sufficient documentation, the CSM.

Standards Bodies

As we said, classification societies require and approve CSMs as part of their general process of approving a ship’s classification. From Marine Insight:

Maritime classification societies were born out of a need to ensure the continued safety and security of the maritime domain with respect to the vessels and the various marine aiding constructions. The role of a classification society is thus quite set and of utmost importance.

In the absence of classification societies for ships, there would be no benchmark or guideline standards for vessels and other constructions to adhere to.

At present, more than 50 classification societies exist. A classification society is required to notate grades or classes for vessels, vessel structuring and its maintenance along with the structuring aspect of various constructions located in the high seas.

(Lloyd’s ranks classification socities by ship’s tonnage classified. So, I certainly hope their not like the ratings agencies before the Great Financial Crash. In that case, however, there are the Big Three. Perhaps 50 entities in different jurisdictions are more likely to keep each other honest.)

However, the structure of CSM document type — instances of which type are approved by the classification agencies — is determined by the International Maritime Organization. Here is the origin of the language quoted above in Det Norske Veritas’s Model! From the International Maritime Organization’s MSC.1/Circ.1353/Rev.2 7 December 2020, “REVISED GUIDELINES FOR THE PREPARATION OF THE CARGO SECURING MANUAL“:

1.3 General information

This chapter should contain the following general statements: 1 “The guidance given herein should by no means rule out the principles of good seamanship, neither can it replace experience in stowage and securing practice.”

So, once again, beneath the boilerplate, and not reducible to it, are the material realities of the ocean and the workers doing the lashing. And not, I might add, the brokers, the executives, or the finance people in their havens.

Conclusion

So Tom Brady’s retiring. Boo hoo. There are workers on container ships who are twice the athlete Brady ever was, if you go by physical risk and skills, let alone the ratio of physical risk to paycheck. Or the social utility of provisioning people’s material needs, as opposed to fan service. And the workers play in a game where the ocean makes the rules, which can’t be bent.

APPENDIX

I found this video fun and interesting — even if it does at points break into Cyrlliic subtitles — but I can’t determine its provenance, and so I didn’t quote from it. But it might be worth watching for a more systematic view:

Booby Hatch is a nautical term? Huh.

Now you know.

Although not as technical as Charlie Sheldon, Rose George’s Ninety Percent of Everything is a lovely read about our dependence on maritime container shipping.

This past October the MV Zim Kingston lost 109 containers in the busy Strait of Juan de Fuca between Vancouver Island BC and the Olympic Peninsula WA due to heavy seas; others caught fire and the vessel had to be temporarily abandoned. 105 of the containers remain unaccounted for, creating a hazard to navigation and causing junk to wash ashore on pristine parkland and First Nations coastlines. Our property fronts these waters; Canadian tribes and non-profits are now complaining that there is no plan for the ship-owner to be held responsible for recovering the containers or their contents.

As for the value of profit-ball players: Bust the Sports-and-Gambling Trusts! We need skilled mariners, not brain-damaged multi-millionaire bread-and-circus justifications for billionaires…

When J. McPhee retired from the NY’r, I unsubscribed. He was that good, at least what I read of his stuff. The book below was written at the zenith of his craft, non fiction become lyrical.

https://www.amazon.com/Looking-Ship-John-McPhee/dp/0374523193

Plus, some relatively recent miscreant of a hire on the NY’r staff started putting Briticisms into everything, as in “focussed.” In the last 5 pages of McPhee’s last book, which was copy edited by said imbecile, he put in “focused” once. Case closed.

> J. McPhee

Isn’t that the one where he describes a captain docking an enormous ship with, like, six inches of leeway on either side?

Fully agree on the sports and gambling trusts point…

How about the cargo lashers’ pay? For this risk and skill, how much are they paid? Do they have unions? How do they learn the skills? What is the worldwide labor picture on that? I’d be curious to see more on the topic for this and other similar professions – like oil rig workers, off-shore fishermen.

Something I didn’t see, though it might have been there or in the supporting documentation, was consideration of the weight of individual containers when building the stack. Presumably you’d want the heavier containers centrally at the bottom with the lightest ones on top, and you certainly wouldn’t want all the heavier ones to one side. Yet against that you’d need to factor in which ones need to come off first if there are several stops on the voyage.

Seems to me you’d need to know the weight of every individual container and when you need access to it before you start and have the construction of the entire stack planned before the first one comes aboard, which in turn means your crane-driver shore-side must be able to identify and access the required containers in the park in the right order and build the stack to plan. That would be no back-of-an-envelope exercise.

They do know the weights, and it’s a complex optimization effort to create the container stow plan for boxes to be loaded at a certain port. It’s because of the requirement to not make the ship top-heavy as you discuss, but there are many other issues to balance: 20’s and 40’s, special equipment like flatracks or tanks, hazardous containers have to go in certain locations, refrigerated containers have special areas where they can be plugged in, and the stowage has to align with the ship’s port rotation, amongst others. You can’t load containers for Hong Kong below those destined for Singapore if Hong Kong is called first. Carriers hate having to unload containers just to dig out containers that are buried.

It’s an amazing business.

> omething I didn’t see, though it might have been there or in the supporting documentation, was consideration of the weight of individual containers when building the stack.

It’s there in the discussion of stowage plans, though I didn’t emphasize it. (The point of the standards is to have a plan, not to specify the actual plan. That is another, and very interesting, topic. Since the today’s plans are created with software…. one would assume there’s fraud, no? A topic for another day.)

Adding, maybe I should do cranes, at some point. I had the picture in my mind that the cranes moved the containers swiftly and smoothly. Swift they are, but smooth they are not! Those cranes swing around quite a bit, as the videos show.

I still believe it might be worthwhile to read about possible future Ocean conditions Hansen et al. describe in the 2016 paper based on Paleoclimate data: “Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2 °C global warming could be dangerous”, https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/16/3761/2016/acp-16-3761-2016.pdf

The Ocean conditions described in that paper might not be kind to Ocean shipping.

> possible future Ocean conditions

Yes, that’s certainly a possibility. There’s some muttering about the very newest and largest ships (like the Ever Given) being vulnerable in ways that are not yet understood.

Thank you, Lambert; this is interesting.

The thought occurred toward the end of my reading that ‘there’s strict rules when money is at stake.’

Perhaps that’s why we have such … ill-considered … public health policies. It’s only people’s lives on the line.

I’m amazed to find one of my comments quoted and will add this further observation: maritime sailors have to train all the time – fire fighting, survival, watch standing – and of course have rules about PPE, helmets, gloves, steel toed boots, as mentioned above – and as I recall we rarely went on deck, if ever, without helmets on. The thing is, much of the work is repetitive and routine, and we are always tired. On the ships I sailed on, most of the deck crew, the ABs, were watch standers, and they stood a wheel watch twice a day for for four hours. But, to increase our take home pay, and do the necessary work, when not standing watch we would work overtime, lashing containers, painting, repairing stuff, chipping rust, cleaning. And in addition to all that were the duties entering and leaving ports, receiving the pilot, letting the pilot off, bow watch in narrow waterways, handling the mooring lines. There were also however STCW rules requring that we be able to get enough sleep, but honestly these rules often had to be ignored when in and around ports. The work is not anywhere near as hard as fishing offshore, which called for 18-20 hour days, but it is still demanding. In one 205 day gig – three round trips New York to Singapore, I kept track of my hours and I worked over 2600 hours, or something like 13 hours a day seven days a week. You get used to it, but you are also tired, dulled out. You have all this training to handle the big disaster and do everything to avoid it, and the definition of success is the thing not happening, but it is HARD to stay sharp for the unlikely event. The work is not highly skilled, whatever that means, but it requires skill, attention, effort, and physical ability, yet at the same time it can be long and tedious, which ios when the danger is highest. All those standards and rules mentioned in this great post are on the walls all through the ship, and we try to pay attention to them, and do, but in the end you’re just working in an environment of heavy, heavy gear, aboard a ship that itself is heaving and rolling and working.

‘

When we lashed the containers, though, leaving the last port before a long stretch at sea, everyone took it damn seriously, because the last thing you want is containers falling overboard or collapsing. As regards weight and crushing (mentioned in an above comment) the ship loading plan at the pier is supposed to manage where the heavy ones go, but not and then mistakes are made. It’s all heavy gear.

” Skilled” and “credentialed” are two different things. Maritime labor is just as skilled as agriculture labor is, even if not quite as ” un-credentialed”.

> ” Skilled” and “credentialed” are two different things.

Entirely. As has been made crystal clear over the past two years, if it was not clear at all. In fact, one might regard credentialization as a process of deskilling…

Are the so-called rogue-waves at sea — things of tales — or are they real? And are the great cargo carriers immune? Would a well-strapped container ship withstand a rogue-wave — if they have more substance more than smoke filling the wind of story-tellers’ tales?

Woooooooooow … thanks for this post. Watching the video now and it’s amazing. I guess I thought they weighed containers before putting them on … ? The bit about heavier containers ending up higher in the stack caught be by surprise!

> thanks for this post

You’re welcome. The weight of containers should be taken into account by the stowage plan for the ship. But to an extent that depends on an honor system involving the shippers, and the crew is responsible for detecting it. I would bet there’s a lot more gaming of weights than we know about, since those are the incentives. That woudl argue, to me, that there’s redundancy in the standards (i.e., that pencil-necked MBAs haven’t been able to optimize them to the point of creating danger).

Re. weighed containers …

Although the video goes into detail on the differences in the various Classification Societies’ weight and strength standards, it mentions only in passing the least quantifiable and possibly most dangerous link in the container safety chain. It’s the shipper who declares weight and content of a container. Since weight and level of hazard affect cost of carriage, there are strong incentives to be less than frank and low probabilty of discovery and sanction unless disaster ensues. Given this system, it’s a wonder there aren’t more disasters, especially fire.

I’ve traveled as passenger on two Winter transatlantic container ship crossings and can underscore a couple points in this post:

1. Pitch and roll factors cannot be overstated. On a vessel with its superstructure astern (instead of amidships), I’ve had to grip the sides of my bed to keep from being thrown on the deck, with the crew asserting that these were not unusual seas (Just joshing’ a landlubber? I didn’t really think so.). I can’t imagine the forces on lashings and twist-locks. And remember from the video … the lashings only go about 3 layers above deck. There can be at least a couple higher layers held only by twist-locks.

2. Vessel flex: the only time I saw the masters (never heard them called “captain”) with their own hands on the controls was during slow final approaches to a mooring. I was told that despite a hull made of very thick steel plate, given vessel size and cargo weight, it’s about as easy to bend as a tin can.

Finally, on “code as law,” safe and efficient load distribution (far too complex for human calculation to be practical, see Reenst Lesemann above) is determined by software, apparently running on standard PC hardware and OSes, and subject to the usual hazards. The safety of the vessel, its cargo, and its occupants depends on the correctness and security of this software and the accuracy of its inputs regarding container weight and hazardous content.

Many a time I’ve looked at those crazily stacked up container ships on the way into my local port here and wondered how they hell they stay on in a storm. Now my question is answered, many thanks Lambert!

This great post evokes memories of my lost youth as a river rat on the great inland waterways of the Midwest. The Illinois river’s locks accommodated barges 3 abreast and 3 long, each one 35′ x 200′. We’d often break our ‘tow’ in two to pass through the locks, pushing 15 barges at a time. Some barges would be empty and high on the water, some low, full of low-value sand, gravel or occasionally crude, strapped together with steel cables and turnbuckles attached to whatever we could figure out to hold things together. At the head of the tow a quarter-mile up from the tugboat it was so quiet we’d startle ducks in shallows. A sudden swerve from the cockpit could explode much of the tow, parting our cables in a cloud of steel smoke and throwing turnbuckles like toothpicks through bulkheads, or you. A half-century ago no one on board had heard of safety helmets, though our National Maritime Union defended working hours pretty well: 6 hours on, six off, 24/7, for 30 days (unless a replacement couldn’t be found or port work had to be done), then a mandatory 30 days on land. 50 bucks a day was better than I could make in a used bookstore, my other dream job. Already in the 70s we were surrounded on tugboats by accommodations for ghost crews long stripped away by management, so safety wasn’t much of an issue either. At least we had a cook, and a washing machine.

I can remember sailings on various Sea-Land container vessels in the 70’s, where the Port Captain would bring a new lashing plan aboard every sailing from the States. Sounds like nothing has changed.

People do not realize the movement of the hull in a seaway. It can twist, bend and contort in all directions and transmit these movements to the containers as I have observed from personal observation from the well decks and main decks at sea.