Yves here. As positions on political issues become even more polarized, this post examines one route for creating social tolerance for expressing dissident views.

By Leonardo Bursztyn, Professor, Department of Economics, University of Chicago; Georgy Egorov, Professor of Managerial Economics & Decision Sciences, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University; Ingar Haaland, Associate Professor, University of Bergen; Aakaash Rao, PhD student in Economics, Harvard University; and Chris Roth, Professor of Economics and Management, University of Cologne. Originally published at VoxEU

Dissent plays a vital role in driving social change, but can be limited when individuals fear social sanction for expressing opinions about controversial issues. This column explores the function of rationales in facilitating dissent on both sides of the US political spectrum. Using a simple theoretical framework, it shows that liberals are more willing to post a tweet opposing movements to defund the police – and indeed face fewer social sanctions – when their tweet implies they have read scientific evidence supporting their position. Analogous experiments with conservatives demonstrate that the same mechanisms facilitate anti-immigrant expression.

Dissent is a vital driver of social change (Adena et al. 2020, Cantoni et al. 2014, Enikolopov et al. 2019, Gagliarducci et al. 2018, Manacorda and Tesei 2016). Dissenters usually draw upon rationales — narratives that provide arguments supporting dissenting causes — when expressing their views. Rationales might spur dissent because they are persuasive – that is, they change people’s private opinions and thus their behaviour. But in many situations, dissent is limited not because people support the status quo, but rather because they fear the social sanctions associated with publicly expressing their opposition. In fact, 62% of Americans agree that “[t]he political climate these days prevents me from saying things I believe because others might find them offensive” (Ekins 2020).

For example, consider a Democrat who opposes the movement to defund the police. She may be reluctant to express this opinion around fellow Democrats, as opposing defunding the police could be interpreted as a signal of racial intolerance. Now, suppose that a new study is widely circulated suggesting that defunding the police would encourage violent crime. This new study might increase her willingness to publicly oppose police defunding even if the study does not change her private opinions, as long as she is able to attribute her views to the study. The availability of this rationale provides an explanation other than racial intolerance for her position. Rationales can provide social cover and facilitate the expression of dissent.

In a new paper (Bursztyn et al. 2022a), we present experiments exploring the power and potential limitations of rationales. Across the political spectrum, dissent is often expressed — and suppressed — on social media, where rationales from both mainstream and fringe sources proliferate (Fujiwara et al. 2020) and where people often face large social costs for expressing controversial opinions. We experimentally investigate the expression and interpretation of dissent on social media, focusing on two controversial domains: liberals’ opposition to defunding the police and support for deporting illegal immigrants.

Experimental Design and Results

In a first experiment, liberal respondents read a Washington Post article written by a Princeton University criminologist arguing that “[o]ne of the most robust, most uncomfortable findings in criminology is that putting more officers on the street leads to less violent crime” (Sharkey 2020). They then choose whether to join a campaign opposing the movement to defund the police and, if so, whether to authorise a tweet promoting the campaign. (Importantly, our experiment is designed such that no tweets are actually posted.) The experimental manipulation varies the availability of a social cover in the tweet while holding fixed other potential motives to post. In the Cover condition, respondents’ tweets suggest that they were shown the article before joining the campaign, while in the No Cover condition, participants’ tweets indicate that they were shown the rationale after joining the campaign. The implied timing in the Cover condition provides these respondents with a social cover – the (implicit) justification that they joined the campaign because they were persuaded by the article’s claims. The timing implied by the No Cover condition removes this social cover. Differences in ‘willingness to tweet’ therefore cannot be explained by the persuasiveness of the rationale, as all respondents in both groups read the article; nor can such differences be explained by respondents’ beliefs that the rationale will persuade their followers, as both versions of the tweet contain an identical description of the article.

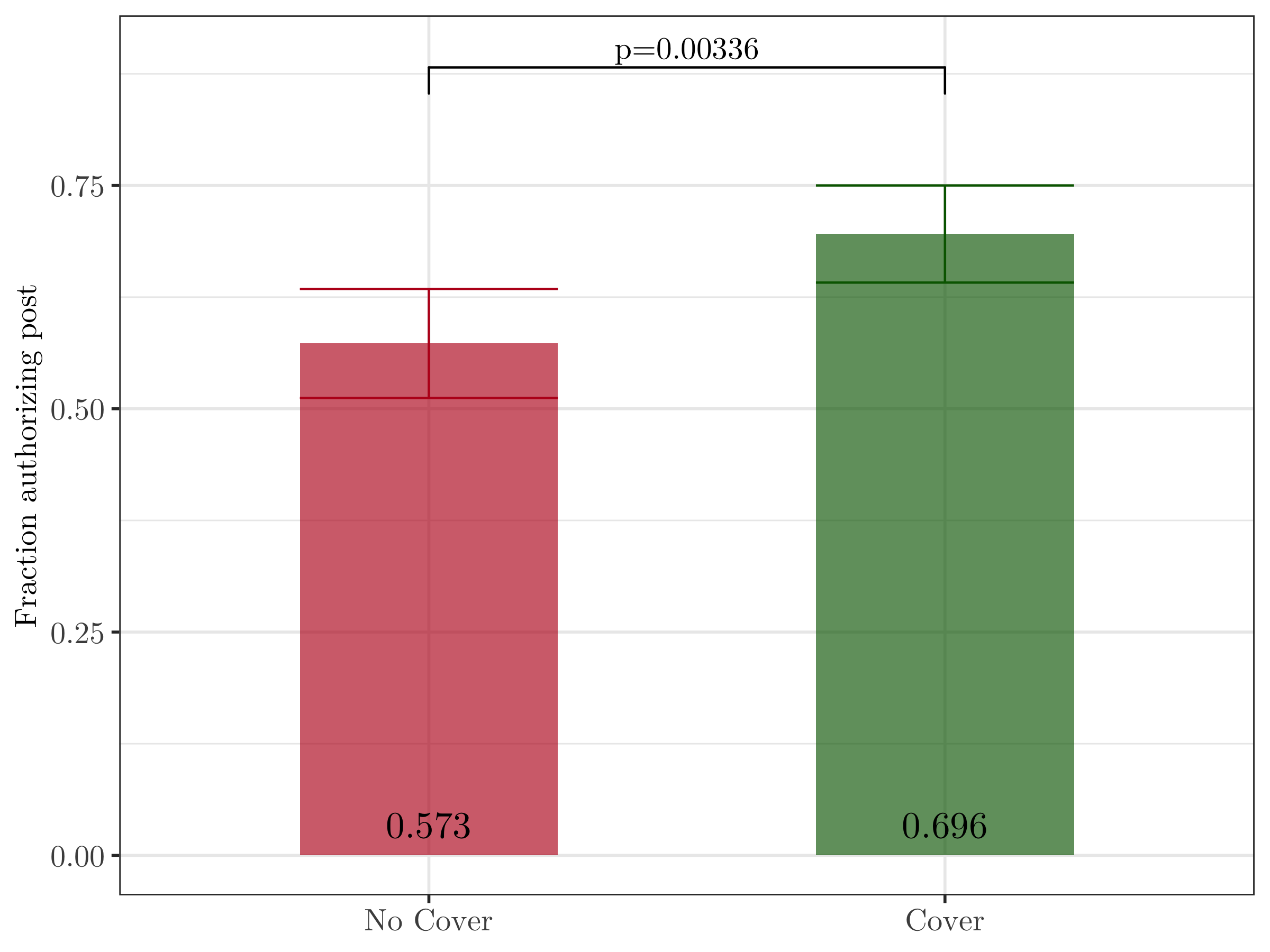

Figure 1 shows that the availability of a social cover strongly affects public behaviour: respondents are 12 percentage points more likely to authorise the tweet in the Cover condition than in the No Cover condition. A placebo and a number of further experiments help rule out other potential explanations for the treatment effect.

Figure 1 Willingness to post anti-defunding tweet

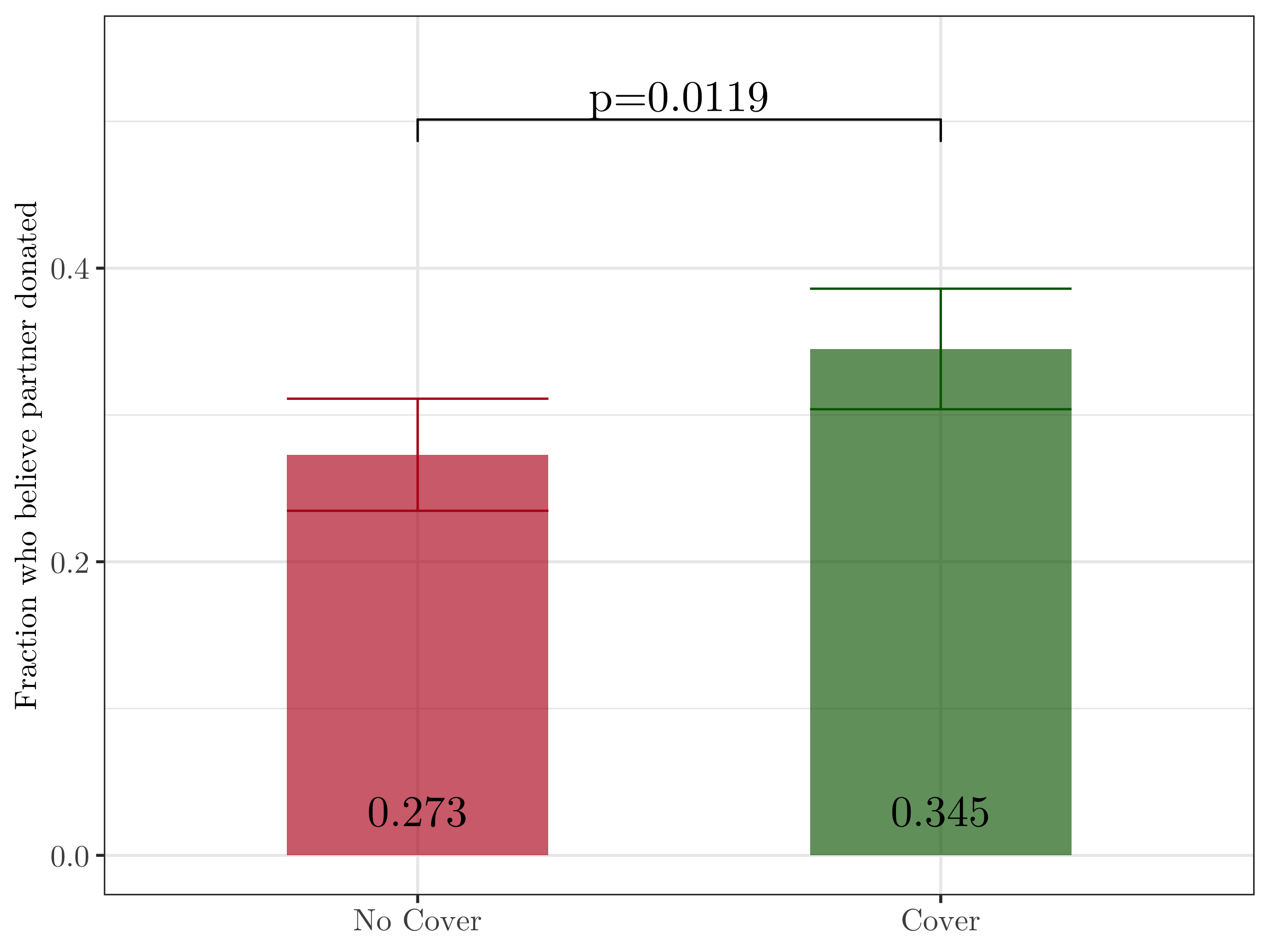

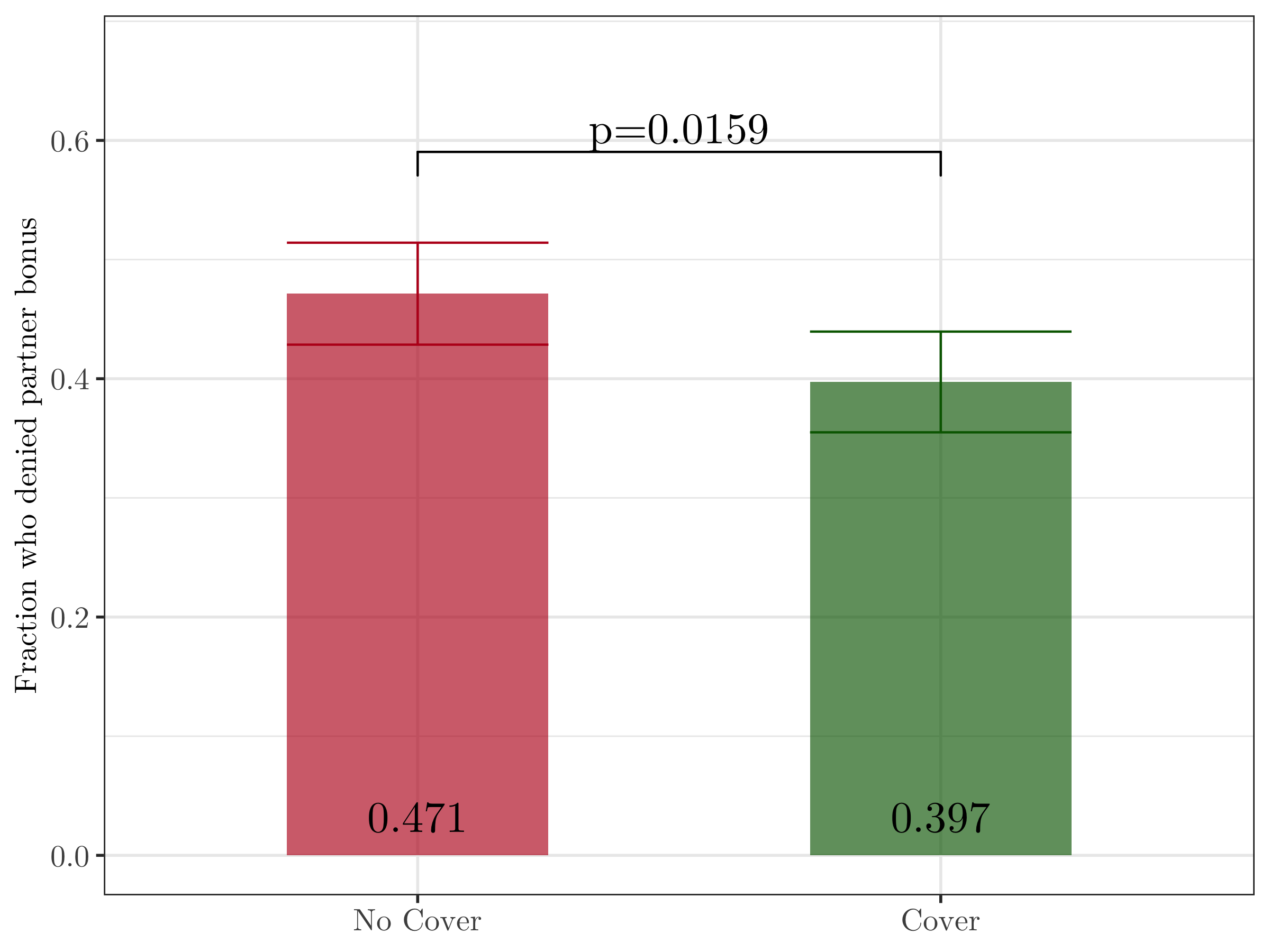

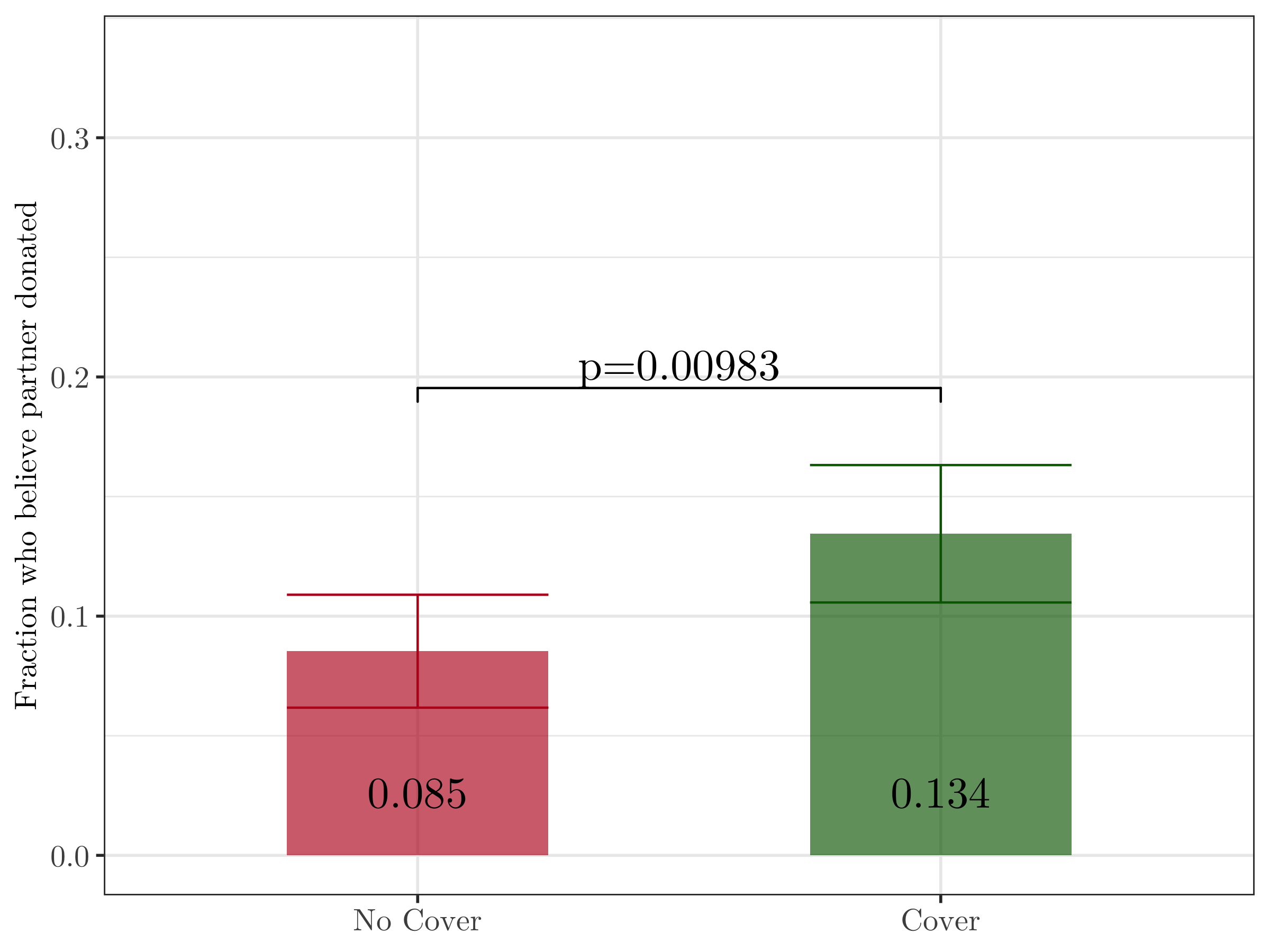

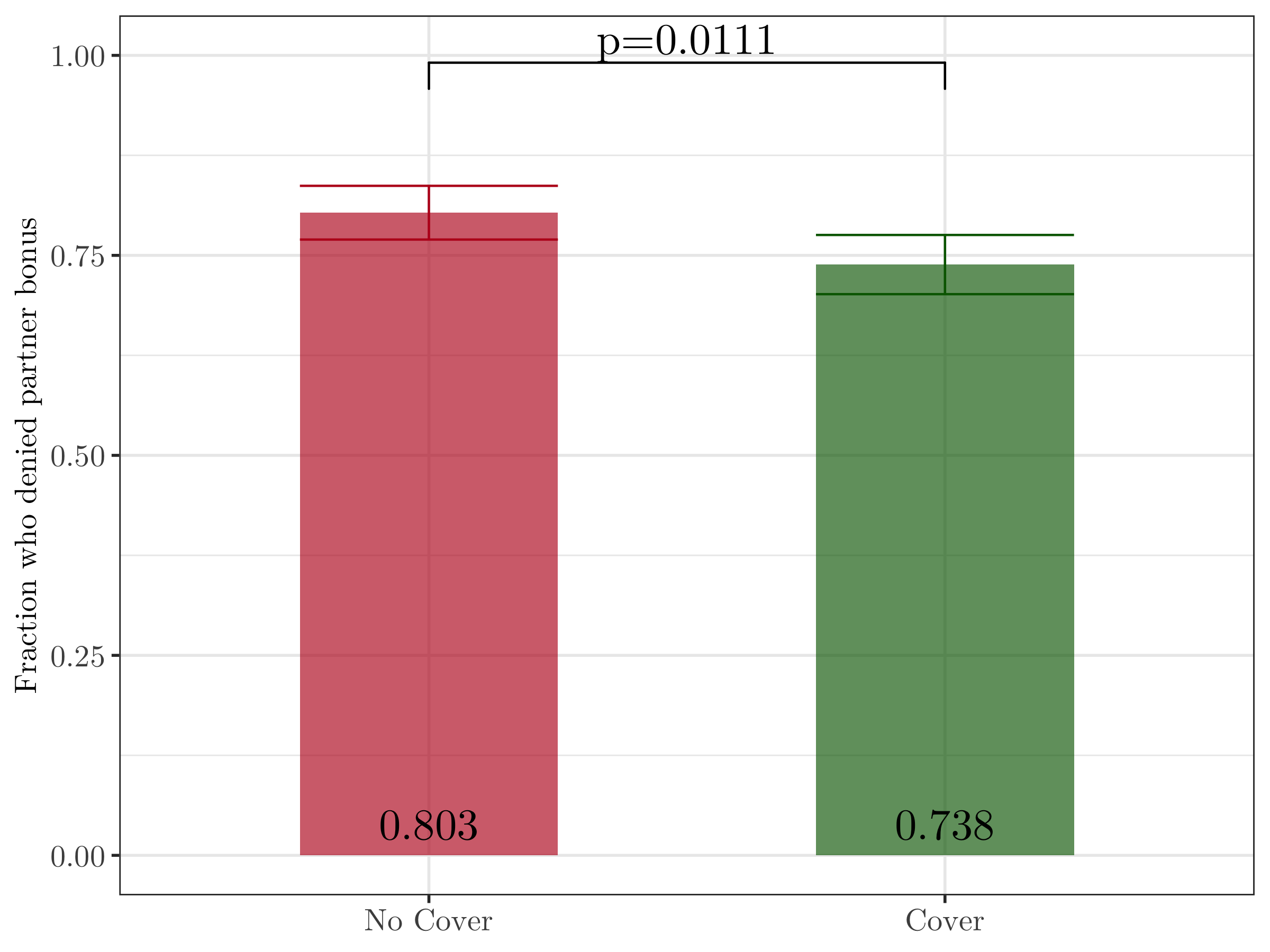

We conduct a second experiment, again with liberal respondents, to examine how the availability of the rationale shifts an audience’s inferences about the motives underlying dissent and the resulting sanctions levied upon dissenters. Figure 2 shows that when interpreting a previous participant’s decision to publicly oppose defunding the police, respondents see participants in the Covercondition as less racially prejudiced than those in the No Cover condition. They are also less likely to deny the Cover participant a $1 bonus, indicating that rationales lower the social sanctions associated with dissent.

Figure 2 Fraction who believe partner donated to NAACP (top) and fraction who deny partner bonus (bottom)

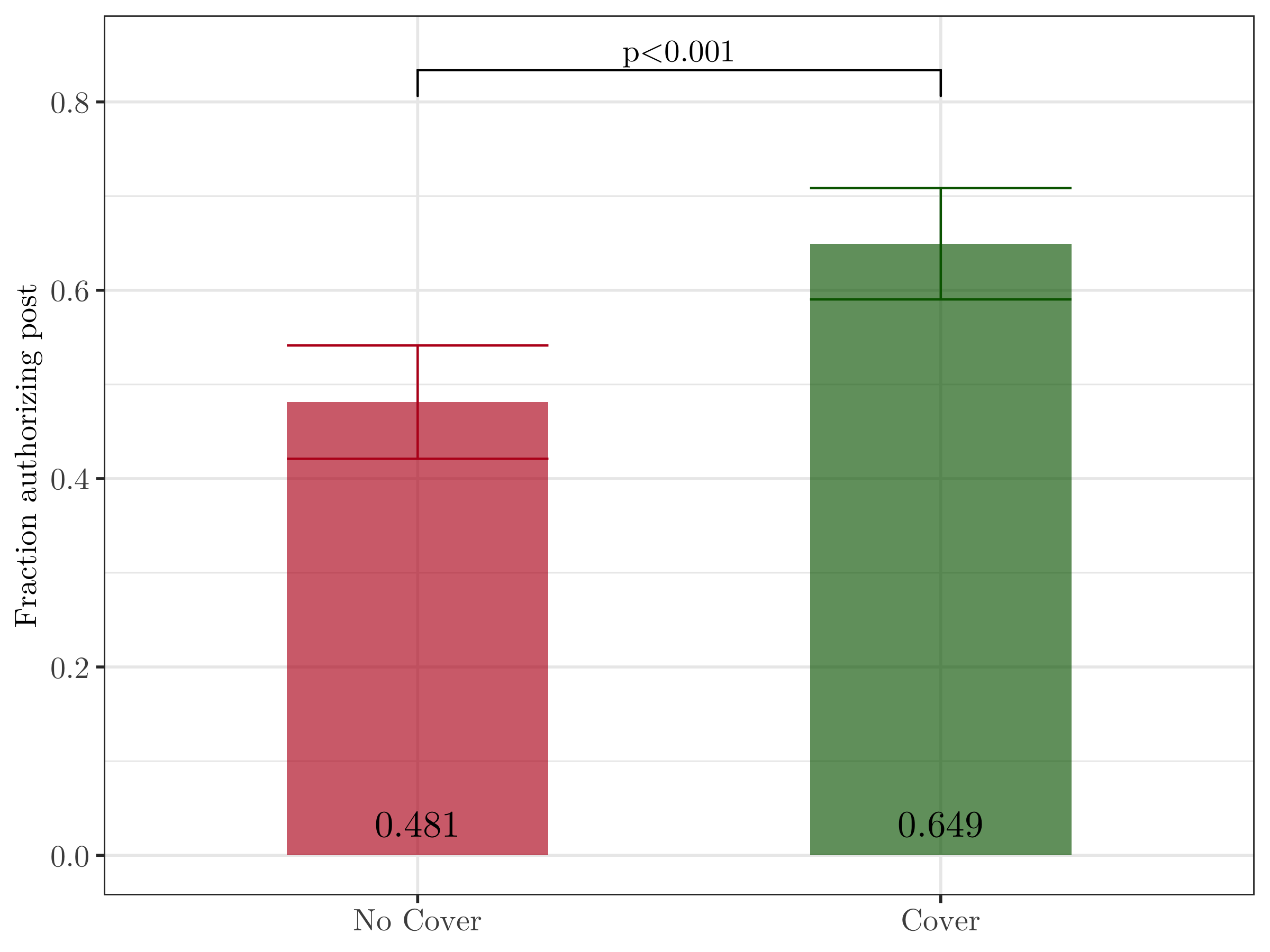

We also study the effects of rationales among a different sample (conservatives), and in a different policy context (anti-immigrant policies). Here, supporting the immediate deportation of all illegal immigrants from Mexico is a stigmatised opinion that people may be reluctant to publicly express, but a similar rationale as studied previously – concerns about crime – may shift inference about motives and thus decrease social sanctions. As in our first experiment, in the Cover condition, respondents’ tweets indicate that they were exposed to the rationale – a clip of the Fox News Channel’s anchor Tucker Carlson arguing that illegal immigrants commit violent crimes at vastly higher rates than citizens – before joining the campaign, while in the No Cover condition, respondents’ tweets indicate that they were exposed to the rationale after joining the campaign. As shown in Figure 3, respondents are 17 percentage points more likely to post the tweet in the Covercondition than the No Cover condition. A further experiment shows that this rationale once again has strong effects on inference: as shown in Figure 4, respondents matched with a participant who chose to post the Cover tweet are 5 percentage points more likely to believe that this participant authorised the pro-immigrant donation and 7 percentage points less likely to deny their matched participant the bonus.

Figure 3 Willingness to post pro-deportation tweet

Figure 4 Fraction who believe partner donated to US Border Crisis Children’s Relief Fund (top) and fraction who deny partner bonus (bottom)

Implications

Our evidence showcases the importance of rationales in facilitating dissent on both sides of the political spectrum. Our theory and evidence highlight the mechanisms by which individuals and institutions can influence public behaviour by shaping the availability of rationales and perceptions of their credibility. Our findings have important implications for how the expression of dissent responds to the availability of new narratives that become widely known.

First, rationales are only effective when observers believe that they genuinely change the dissenter’s beliefs. An obscure or non-credible rationale likely fails to shift inference, and may even backfire, if it is informative of the dissenter’s underlying type. In the extreme, if only intolerant people tend to read a particular source, citing a novel rationale provided by this source will fail to generate social cover. Thus, the endorsement of rationales by prominent figures such as politicians or celebrities may generate particularly large ‘social amplifiers’. Such figures may not only be more credible and directly persuade more people, but they may also be able to generate common knowledge such that dissenters can claim they were exposed to the rationale without seeking it out directly from stigmatised sources. Anti-minority politicians, for example, may enable supporters to speak their mind more openly and spread propaganda through their social circle, an effect documented for Nazi propaganda in the Weimar Republic by Satyanath et al. (2017). In another paper (Bursztyn et al. 2022b), we apply this framework to understand scapegoating of minorities during crises. The strength of the ‘social amplifier’ channel depends not only on the number of individuals who hold stigmatised views, but also on the number of individuals who could not express these views prior to the rationale becoming widespread.

Conversely, groups seeking to suppress dissent have strong incentives to silence or marginalise potential sources of rationales because these tactics reduce the perceived probability that people will be exposed to rationales ‘by chance.’ Such tactics may include censoring certain figures or otherwise disallowing them a public platform (e.g. disinviting campus speakers), or branding particular media sources or speakers as fringe. This helps explain why censorship techniques such as China’s Great Firewall can be very effective in suppressing dissent, even when citizens can bypass them with relative ease (Chen and Yang 2019). If successful, these tactics can create and sustain a ‘political correctness’ culture in which, for better or worse, certain rationales are ineffective because citing the stigmatised source undermines social cover. By questioning the credibility of rationales or tying them to stigmatised positions, a vocal group can silence a majority.

See original post for references

Weird. An academic article vs Tucker Carlson. Cover to express their worst selves versus cover to express a more nuanced view. All kinds of stuff mixed up here, and it is reflected in the further examples given as well.

Another academic study from social scientists with physics envy trying to quantify something that can’t really be quantified. Wouldn’t it be easier to just encourage people to grow a, or a pair of, the gonads of their choice and speak their minds? ;)

Everyone with any intellectual honesty should watch a week of Tucker Carlson’s reports, free on youtube, then make up your mind. Also, read the transcript of Putin’s speech on Ukraine.

The same people that ran around talking about mushroom clouds before the invasion of Afghanistan are now mouthing reports of Russian atrocities.

Those people deserve the politicians that they elect.

I have a FB account, mainly to keep track of my musician friends.

I’ve been disappointed in the 100% seamless anti-Russia, stand-with-Ukraine virtue signalling going on, a lot of it quite rabid.

No awareness of Amerika’s part in the whole mess.

Keeping my mouth shut.

I didn’t know it was so easy to fool everybody…some of the time.

I feel like I’m generally pretty skeptical when it comes to the general intelligence and education level of Americans.

The past week has shown me that I’m clearly not skeptical enough.

The jingoism does seem even more intense than that in the runup to the warcrimes committed in Iraq. Maybe it seems this way because there was no social media in the early aughts.

Too bad it didn’t stay that way. I wish there were a way to put that genie back in the bottle but there likely is not, short of a complete societal collapse. Only consolation is perhaps seeing Zuckerberg gnashed in Old Nick’s fetid maw in the 9th circle of hell someday. A guy can dream….

Now that interior mask mandates are being discarded, it’s a consolation to know that anti-Russian vituperation equals greater Covid resistance… uh, right?

Pass the Victory Gin…

Me? I’m going to say something that will probably shock a lot of the FB crowd, but here goes:

I have been learning Russian for several years. During the pandemic era, I have been putting this effort on hold because it’s been so difficult to find people to talk to.

Well, guess what’s off hold. Learning Russian, that’s what!

Why? Well, that’s simple. I live in Tucson, Arizona, a city that’s famous for welcoming refugees. And I think that more than a few Ukranian refugees are about to come our way.

Since Russian is widely spoken in Ukraine, I think that these new Tucsonans will be looking for someone to talk to. So, here I go again.

Link to the start of my Russian journey: https://realrussianclub.com/russian-language-learning/

I’d add a caution. A friend was trained by the USAF to be capable in Russian for signals intelligence analysis. After leaving the service and working for an airline, he listed himself with an airport to help with translations. He often helped Volga-Dnepr crews when they were transiting the station.

He had several experiences with Russian speaking travelers from former USSR satellite states giving him a hard time for how he could speak the language, as they all accused him of being from some old country group they didn’t like. The poor guy was from the same trailer park in the US that Iggy Pop came from and from a Protestant family in the US for several generations.

Thank you for that link, Slim!

Same here in Finland, and with my Dutch facebook. If you dare say something about the historical role of NATO, US and mention the legion scholars and ambassadors who have warned Russia does not want NATO on its doorstep, you get labelled a Putinista.

I have at some point studied international relations, in the late 1990s, and we had SO many discussions about NATO, about Kosovo, about the end of the Cold War…I even visited the NATO HQ in Brussels, where we got the exact narrative of NATO providing security in Europe. But me and my colleagues dared to ask questions – although we did not get replies of course.

In these recent weeks I have tried to explain all of this in Twitter, Facebook and I got a real amount of vitriol. Which is mentally not nice. But since I have this background in IR, I don’t care what people say – they only look at this immediate war. And to be clear, the attack IS morally wrong. It should not be dissent to point out the role of US/NATO that brought us to this point.

But this will have consequences for my current home country’s (Finland) view on Russia and view on NATO. Fortunately no immediate plans to join NATO.

I was wondering what the authors mean by “liberal” (and a few other terms). I probably don’t need to explain my doubts. In any case, one has probably heard the theory that the more widely read and better informed people are or become, the more it reinforces their original ideas. Meanwhile people with actual power can do things besides argue to inconvenience those whose beliefs or activities they don’t approve of.

This is an interesting topic. I can’t know where to start to disagree other than to tell my experience in speaking out. When you speak out be prepared to loose everything. If the main stream voices in your community or county or state or country are greater than yours you will be crushed. You will be a social pariah if it’s local. If you have a business in that same community be prepared for the behind your back attacks on people telling everyone in the community not to shop at your store.

If you are a young person with nothing to loose, still living at home, you can wade through the personal attacks, hate mail, death threats, even beatings and carry on. Your parents may not be so lucky. They can loose jobs, loose elections, loose friendships over a stance you take. It’s a vicious world out there for people who speak out.

It is even worse today with the draconian knowledge that the government has and their ability to

use it against you. But hey, it’s America Jake. Land of the free.

Weird that they chose two positions (“don’t defund the police” and “deport all illegal immigrants”) that are extremely popular among politicians and the punditocracy (though not across the political spectrum) as examples of dissent.

Not much use to those of us who want to disband NATO, end domestic spying, or democratize the Presidency and Senate and Supreme Court, etc.

What would be interesting is to consider some of the basic conceptual foundations. When it’s millions and billions of people, it’s not so much culture and politics, as it is biology and physics causing what is going on.

To culture, good and bad are some cosmic conflict between the forces of righteousness and evil, while in nature they are the basic biological binary of beneficial and detrimental. The 1/0 of sentience.

This is because a community has to function as a larger organism, so much of culture arises as social control mechanisms. For example, logically a spiritual absolute would be the essence of biological sentience from which we rise, not an ideal of wisdom and judgement, from which we fell. Ideals are not absolutes and treating them as such tends to empower the most close minded.

Consider how memes go viral in society and how it has always been so, since long before there were humans. So the concept of the group as a single organism, a hive mind, is integral to our deep sense of society. This would also be applied to many aspects of reality, consequently the origins of theism. Poly, pan and mono.

By the time of the Ancient Greeks, the belief systems had solidified into the classic pantheon we read about today. It was in pantheistic societies that democracy and republicanism originated, as that was part of how they analogized the multiculturalism that developed as various groups learned to live in relative harmony, without identifying as a single group. In fact, monotheism was analogous to a monoculture. One people, one rule, one god. Remember the formative experience for Judaism was being isolated in the desert for forty years.

Gnostic Christianity arose in the Greek world, as a way to breath new life into the classic religions, as the story of Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection was somewhat analogous to the old tradition of year gods. The son reborn in the spring, of the sky god and earth mother. It was the basis of the Trinity.

Though the Romans adopted it as a state religion as the Empire solidified after a few centuries of fighting among the oligarchs, as to who was Caesar. As such it was to deify the Big Guy on top. So the original meaning of the Trinity had to be obscured, because the Catholic Church was the eternal institution. Which made monarchy the default political model for the next 1500 years. As the West went back to more populist forms of government, it required the separation of church and state, culture and civics.

The two basic dynamics are synchronization, which is centripetal, versus harmonization, which is centrifugal. So there are nodes and networks, organisms and ecosystems, particles and fields. When the crowd starts spiraling into the abyss, run for the hills. Logic is as irrelevant as waving a stick at a fire.

Remember when French fries were called freedom fries, because the surrender monkeys wouldn’t submit to our need to blow up Iraq. Multiply it by a thousand.

Thanks for the essay.

That’s all I can say about it. \s

The ABC TV channel in Australia (govt funded channel) has a panel TV show called Q&A running since 2008 where they discuss various societal issues of the day with questions from the audience. Normally they have speakers from both sides of whatever topic they are discussing. It can get forthright and probably normally could be said to have a left bias but they are generally pretty fair in letting voices be heard.

On part of last nights where on part of the show they discussed the Ukrainian war. A calm young man from the local Russian community gave a view that he had been “pretty outraged by the narrative created by our media depicting Ukraine as ‘the good guy’ and Russia as ‘the bad guy’. Believe it or not, there are a lot of Russians here and around the world that support what Putin is doing in Ukraine, myself included.”

Sasha then went on to claim that Ukrainians had been responsible for the deaths of 13,000 ethnic Russians living in the country since 2014. “Where was your outpouring, or even concern, for those thousands of mostly Russians,” he asked.

10 minutes later during another topic, suddenly the host of the show then asked the young man to leave the studio and had him removed because he was ‘uncomfortable with him being here. You can ask a question but you cannot advocate violence’.

https://www.theage.com.au/culture/tv-and-radio/please-leave-stan-grant-ejects-pro-putin-audience-member-from-q-and-a-set-20220303-p5a1kw.html

Don’t think that anyone has been ejected from the show before. And its a show where differing opinions are supposed to be heard.

The Russophobia and cancellation is off the charts. I can imagine this is how we ended up with Japanese internment camps here in WWII

That is amazing that. The host would have been wearing an ear-piece so what is the bet that there was a lot of discussion behind the scenes with the TV station and some government people what to do. And when they decided to censor that young guy, that the host got his orders over his ear-piece to eject him which was why the 10 minute delay. Remember what George RR Martin said?

“When you tear out a man’s tongue, you are not proving him a liar, you’re only telling the world that you fear what he might say.”

It’s a shame they didn’t do this in 2003 to anyone who supported the Iraq war, including John Howard.

But yes, interesting that a question that was framed as “How do we look at ‘both sides’ of this conflict, without diminishing the magnitude of what’s happening on the ground in Ukraine?” results in a pro-Russian audience member being ejected from the audience.

Oh no, who will think of the brave few who oppose defunding the police!

Wherever could they air their views without fear of consequences?

You know, those consequences. The grave, real-world consequences that this attitude could bring: people will be mean to them on Twitter.

In the lifetime of people still alive being made unemployed, destitute, ostracized merely for going to a meeting or being a member of a perfectly legal organization decades earlier was a very real threat.

For the moment it might only be mean tweets, but in the United States, censorship can be quite heavy and brutal. One can always legally say almost anything and the Supreme Court will back it up; however, members of the security state will likely put under direct observation. Back when HUAC or the House Un-American Activities Committee would subpoena anyone that they wanted to interrogate.

“Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” It was the standard question. If you did not answer in full and name names, the consequences would be severe: immediate unemployment and ostracization from family, friends, and neighbors. All of them, usually. The news would mention your name and then there is what Congress could do to you. Testify or go to jail? Although usually just having your name splattered everywhere would be bad enough. So, rat out your friends and have them destroyed or be destroyed. Then pray that whatever you said would be believed.

Mind you, it could be something you were accused of saying or doing twenty years before by someone, which could get the FBI to your door or the door of family, coworkers, and friends. Would you risk having Hoover’s boys coming to you if you did not ostracize them or if they did not ostracize you? Fired, broke, your children, wife, husband, best friend all being questioned by other people and possibly getting in trouble themselves for not being sufficiently anti-communist. The saying was “better dead than red.”

What anyone should be terrified of is of the state brainwashing or scaring people into doing this to you. Of having people in dark suits following you from job to job, home to home, asking questions from your neighbors and coworkers or your children’s teachers. People will throw others to the wolves to save themselves or their families. Lying just to show what a loyal American they are. And of course, with the new spyware everywhere…. but merely being suspected or being fingered would be enough as your innocence would not really matter.

The details of a future(current?) regime of censorship and punishments will be different, but the results will be much the same although there’s all those prisons built in the past thirty years. But, yes. It is mean tweets for now.