Yves here. Sadly, this model of more broadly shared prosperity might have been possible, but it seems like a pipe dream now given climate change, inflation, food scarcity, and more intense competition for other scarce resources.

Even thought this article does a good job of tracing some of the immediate factors that have led to worker in the US working even harder over time, it greatly underplays the coercive nature of the need to sell labor as a condition of survival in a capitalist system. This is why ordinary people can’t have nice things like a lot of leisure. Cribbing from a 2020 post on precarity:

Robert Heilbroner identified this tendency in his 1988 book, Behind the Veil of Economics. A major focus was contrasting the source of discipline under feudalism versus under capitalism. Heilbroner argues it was the bailiff and the lash, that lords would incarcerate and beat serfs who didn’t pull their weight. But the lord had obligations to his serfs too, so this relationship was not as one-sided as it might seem. By contrast, Heilbroner argues that the power structure under capitalism is far less obvious:

This negative form of power contrasts sharply with with that of the privileged elites in precapitalist social formations. In these imperial kingdoms or feudal holdings, disciplinary power is exercised by the direct use or display of coercive power. The social power of capital is of a different kind….The capitalist may deny others access to his resources, but he may not force them to work with him. Clearly, such power requires circumstances that make the withholding of access of critical consequence. These circumstances can only arise if the general populace is unable to secure a living unless it can gain access to privately owned resources or wealth…

The organization of production is generally regarded as a wholly “economic” activity, ignoring the political function served by the wage-labor relationships in lieu of bailiffs and senechals. In a like fashion, the discharge of political authority is regarded as essentially separable from the operation of the economic realm, ignoring the provision of the legal, military, and material contributions without which the private sphere could not function properly or even exist. In this way, the presence of the two realms, each responsible for part of the activities necessary for the maintenance of the social formation, not only gives capitalism a structure entirely different from that of any precapitalist society, but also establishes the basis for a problem that uniquely preoccupies capitalism, namely, the appropriate role of the state vis-a-vis the sphere of production and distribution.

And having ordinary workers receiving the perquisites of the well off is too much for a capitalist system to endure. Michal Kalecki explained in his 1943 Essay on Politics and Ideology why even full employment is threatening. A key section:

We have considered the political reasons for the opposition to the policy of creating employment by government spending. But even if this opposition were overcome — as it may well be under the pressure of the masses — the maintenance of full employment would cause social and political changes which would give a new impetus to the opposition of the business leaders. Indeed, under a regime of permanent full employment, the ‘sack’ would cease to play its role as a ‘disciplinary measure. The social position of the boss would be undermined, and the self-assurance and class-consciousness of the working class would grow. Strikes for wage increases and improvements in conditions of work would create political tension. It is true that profits would be higher under a regime of full employment than they are on the average under laissez-faire, and even the rise in wage rates resulting from the stronger bargaining power of the workers is less likely to reduce profits than to increase prices, and thus adversely affects only the rentier interests. But ‘discipline in the factories’ and ‘political stability’ are more appreciated than profits by business leaders. Their class instinct tells them that lasting full employment is unsound from their point of view, and that unemployment is an integral part of the ‘normal’ capitalist system.

By Jan Behringer, Head of Unit (Macroeconomics of Income Distribution), Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK), Martin Gonzalez Granda, PhD Student, Institute for Socio-Economics (IFSO) and the University of Duisburg-Essen, and Till van Treeck, Professor, University of Duisburg-Essen. Based on a text published in German on the research blog of the Institute for Socioeconomics at the University of Duisburg-Essen. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

Keynes promised shorter working hours and greater prosperity by now. As remote as it sounds, that vision is still possible.

Why haven’t working hours in rich industrialized countries declined more sharply or even increased at times since the early 1980s? And why do average working hours vary so much across rich economies? These are the questions addressed in our paper Varieties of the rat race. Working hours in the age of abundance.

These questions are interesting and especially poignant because there are indications that rich societies have perhaps long been in a position to move into an “age of leisure and abundance” due to the level of productivity they have achieved. The famous economist John Maynard Keynes predicted in his 1930 essay on The Economic Possibilities of Our Grandchildren that the conditions for significantly reduced working hours (3-hour days or 15-hour weeks) should be in place by 2030. While Keynes’ predictions regarding productivity growth have actually been exceeded over the past nearly 100 years, the obstacles to more leisure time are primarily socio-political in nature.

Based on an empirical analysis of 17 European countries and the U.S. for the period 1983-2019, we conclude that lower income inequality, coordinated wage bargaining, and strongly developed public services can contribute to short working hours. This result is relevant in that shorter working hours could make an important contribution to addressing several of society’s most pressing current challenges – climate change, gender equity, and social cohesion.

The saturation of middle-class needs in the “Golden Age of Capitalism” (ca. 1950-1980)

What is the minimum amount of money a family needs to do well in life? In the United States, this question is regularly asked in a large-scale survey. How respondents’ answers have changed over time since World War II says a lot about the evolution of American society, and likely also about the evolution of capitalism in rich countries as a whole.

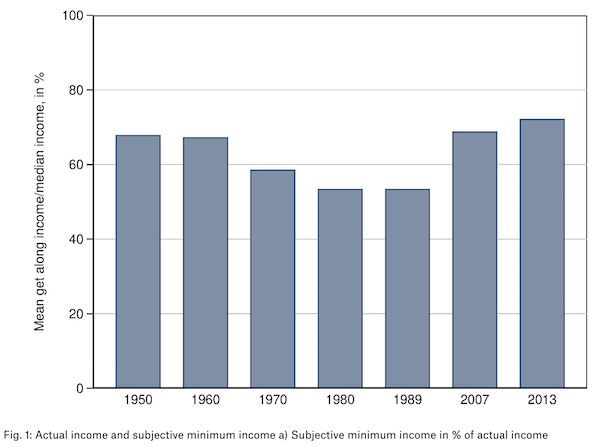

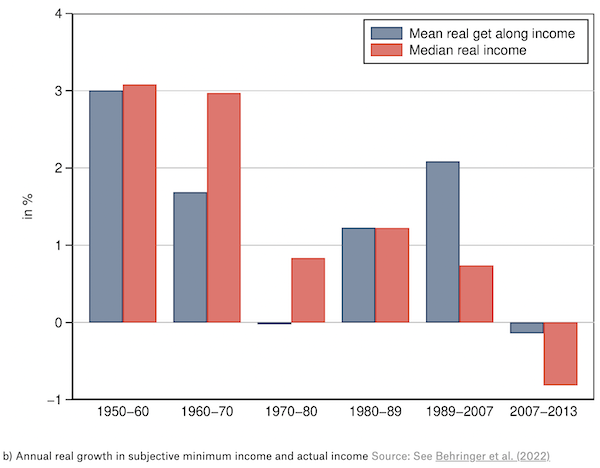

In 1950, on average, the families surveyed thought they needed about 68% of the actual median income at the time to live satisfactorily (Figure 1). By 1980, after three decades of strong income growth across all strata of the population, 53% of median income was already sufficient for a satisfying life for the families surveyed. During the 1950s and 1960s, while aspirations for a satisfactory standard of living increased, they did not increase as much as the actual incomes of the middle class. And, interestingly, the growth of these aspirations actually came to a complete halt during the 1970s. Apparently, a certain saturation of basic material needs had been reached.

Fig. 1: Actual income and subjective minimum income a) Subjective minimum income in % of actual income

b) Annual real growth in subjective minimum income and actual income Source: See Behringer et al. (2022)

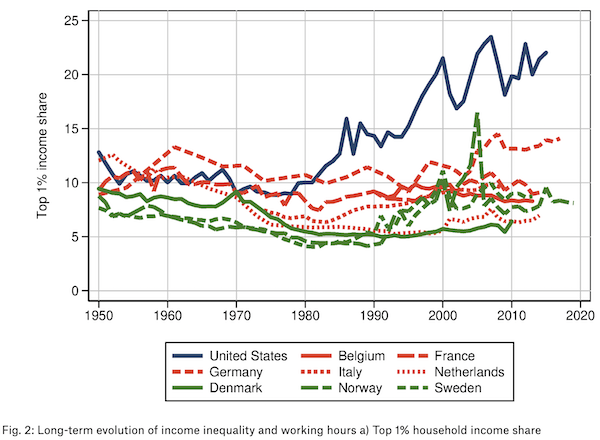

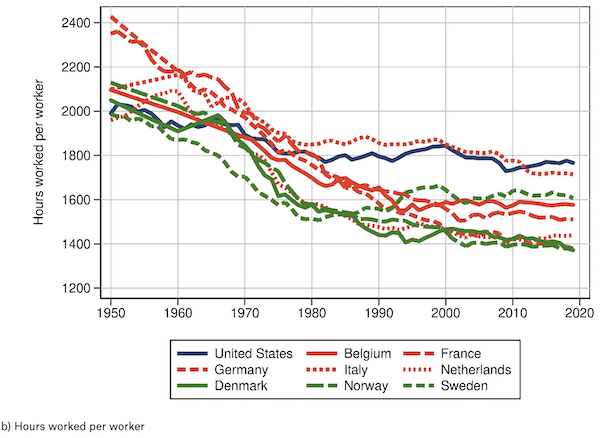

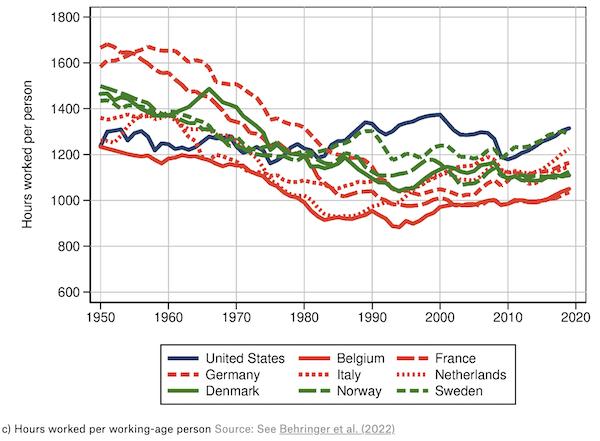

The three postwar decades, often described as the “golden age of capitalism,” also displayed a remarkable reduction in average annual working hours. This was the case not only in the U.S., where the hours worked per year by employees declined by about 200 hours but in virtually all industrialized countries (Figure 2). From the perspective of neoclassical economics, leisure time behaved like a “normal good”: as they got richer, people consumed more leisure.

It almost seems that, as Keynes put it in his 1930 essay, “the economic problem” was more or less solved: as income levels rose, people’s material needs would be met and they would now prefer to devote more of their time to non-economic purposes rather than continuing to work long hours.

The reestablishment of material neediness in the “neoliberal age” (from ca. 1980)

But things turned out completely differently. Since the 1980s, material saturation has given way to a new and growing sense of material deprivation among large segments of the population. The level of income that families consider minimally necessary to make ends meet has risen again over this period, and at increasing rates of growth. When the global financial crisis hit in 2007, the subjective minimum income was again 68% of the actual median income, just as it had been in 1950 (Figure 1).

Average hours worked by employees did not decline in the U.S. after 1980; instead, they rose again until the early 2000s before remaining at a high level. In fact, annual hours worked per working-age person rose steadily by about 150 hours from 1980 to 2000, a trend interrupted only by two deep recessions. Working hours in other industrialized countries show broadly similar trends over time, but with some differences in the extent and timing of these developments (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: Long-term evolution of income inequality and working hours a) Top 1% household income share

b) Hours worked per worker

c) Hours worked per working-age person Source: See Behringer et al. (2022)

Inequality, decentralized wage bargaining, and poor public services as reasons for long working hours

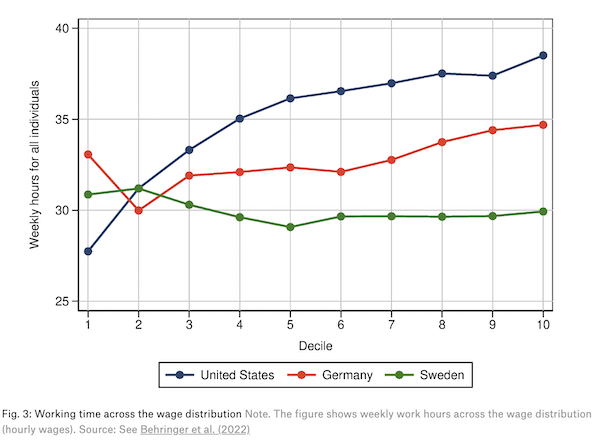

One finding of our macroeconomic panel analysis is that top household income shares are positively related to average working hours. Income inequality has increased since the 1980s, first and more strongly in the U.S., with a time lag and less strongly in Europe (Figure 2a). Two phenomena are striking. First, as inequality has risen, average working hours have fallen more slowly over time than in earlier decades or have even risen again (Figure 2b-c). Second, it is striking that employees with higher hourly wages in countries with high inequality at the upper end of the income distribution now tend to work longer hours than employees with lower hourly wages (Figure 3). Both developments are historically unusual. This is because they contradict the observation of economists that societies or individuals with high incomes consume more leisure time.

Our explanation for this historical anomaly is upward status comparisons in the context of rising income inequality. In particular, the upper-middle-class emulates the consumption norms of the rich and sacrifices leisure time to do so. Because the rich also increase their spending on status goods such as housing, education, etc. as their incomes rise, the middle class feels pressured to keep up. After all, what constitutes a “good place to live” or a “good education” is essentially defined in comparison to the standards that the upper-income groups largely determine. If, on the other hand, the gap in the living standards of the rich becomes too great for the lower-income groups and they are left further and further behind, these groups are often left with nothing but resignation, i.e. giving up the “rat race”.

Fig. 3: Working time across the wage distribution Note. The figure shows weekly work hours across the wage distribution (hourly wages). Source: See Behringer et al. (2022)

Another finding of our empirical analysis is that centralized wage bargaining and government social transfers in-kind (but not in cash) are negatively related to working hours. One possible explanation is that centralized wage bargaining mitigates status conflicts because workers can collectively decide against a “positional arms race” at the expense of leisure. The fact that public services (social benefits in-kind), unlike monetary social transfers, are associated with lower hours of work may be because the direct provision of goods and services reduces the need for status-oriented private spending on goods and services.

Finally, we also examine the importance of education as a positional good. The extent to which the education sector is organized through private markets is found to be associated with longer working hours among workers who themselves have high levels of education.

Inequality also makes leisure time more stressful – the example of raising children

Our findings can also be seen in the context of family economics research by Matthias Doepke and Fabrizio Zilibotti. The authors show that the intensity of parenting styles is positively related to income inequality. In highly unequal societies, the loss of status associated with relatively low educational attainment is particularly large. This seems to explain, in large part, why it is precisely educated and high-income parents who spend more time and money on children’s education when income inequality is higher.

Doepke and Zilibotti point out that parents in the 1970s and 1980s took a much more relaxed approach to child-rearing. Especially for the educated and comparatively high-income middle class, which attaches great importance to children’s educational success and labor market prospects, both work life and leisure time (which includes time spent with children) have therefore become more stressful in many respects as inequality has increased. Parents with less educational attainment, on the other hand, are much less prone to “helicopter parenting.” Again, the explanation is that parents with low educational attainment are more likely to resign due to the large status differences and therefore more often do not even try to enter the “rat race” for the best education.

What to do about “neediness despite abundance”?

Social cohesion is currently being severely tested throughout the Western world. The overarching problem seems to be status concerns related to increased economic inequality, which have spread well into the upper-middle class.

At the same time, there seems to be a great need in large sections of society for more leisure time and to get off the hamster wheel. The Coronavirus pandemic has made many parents in particular aware that they have little time leeway to deal with unexpected additional stress. Among the younger generation, the view is increasingly widespread that the prospect of ever further increases in production and income is not only not meaningful, but also ecologically questionable.

However, a reduction in working hours is likely to remain unattractive or unattainable for many people as long as high inequality, incomplete collective bargaining agreements, and inadequate public services foster a feeling of “neediness despite abundance.” In our view, an unconditional basic income, which many are toying with, does not offer a solution as a purely monetary social benefit. More promising would be an expansion of “unconditional public services” in areas of key positional goods (especially housing, transportation, and education), combined with labor market reforms (e.g., four-day week, regular sabbatical years, job guarantee, subsidized free time for service to the common good).

I don’t know anyone angry because they’ve grown increasingly insecure in their status. I know lots of people who are angry because they feel stress about their ability to house and feed their family. Maybe that’s because I spend more time with lower income people than I used to. But the rich are very public about their wasteful opulence, and their control of politicians, and the contrast with most people’s situations is stark.

If the author says status concerns is the issue but status is mostly a middle class concern (as here):

…. Then it seems like he’s pretending middle class concerns are everyone’s. Ideally, there’d be no rat race, but that would require physical confrontation with the formal and informal thugs working for capital (ie cops/military and their privately-hired equivalent) to change how abundance is distributed and social life is structured.

Thank you for the laugh. The nuevo-rich are still at it… i started making economic choices when Victor Posner bought Sharon Steel in the early 1970’s and knew I was screwed. Crawled into the bottle for a decade or so, popped out in the early 1980’s. Back to school, got a trade and moved to Miami. After 9/11 things appeared worse, 401k evaporated and realized I can live on self employment @ 20hours a week, and cover my nut. @75 yrs today, and as draftee the VA does my health care, i have a cleaning lady every other week, and a wash and fold across the street. i have enough. Ya, I’m bragging. Cause and effect, we make our choices.What’s the old Warren Buffet quote,’… you were born in the USA, you already won the lottery…” for as longs as it lasts.

…even ol’ WB knows the ping-pong balls are weighted. It’s not who your mother country is, it’s whom your actual mother is. Just take a look at the effects of wealth on educational attainment.

I think the authors are broadly correct in their interpretation, though they could be clearer in emphasizing much more strongly how the pursuit of “rivalrous” goods, particularly education (which in the US is peculiarly tied to real estate in K-12?) drive down leisure preference at the upper end (but not the very top) of the income and wealth distributions. I say particularly in education because it speaks to dread of downward mobility as well as being a crucial element of social and class reproduction.

Yves’ introduction is particularly helpful in explaining why those who benefit most from current arrangements choose price stability over full employment over and over again, risking social and political upheaval in the process; which always works — until it doesn’t …

Judging by news this week, it’s starting not to (work).

which in the US is peculiarly tied to real estate in K-12?

In the US public schools are funded by residential property taxes. Nicer neighborhood, better public school. Good private schools are expensive in K-12, you want to save as much as possible for college, so for a lot of upper middle class families it made more financial sense to get a good house in a good school district than live in a cheaper house and pay for a parochial school (that is more of a lower middle class thing).

Econ dilettante that I am, I jump on over in my mind to the subject of: for whom it doesn’t “work.” Seems pretty conspicuous. It astounds me how people don’t grasp which workers are holding up this country, and how the system screws them [leisure time for them ha; they’re too tired to leisure it up]. Often, though, even the workers themselves don’t grasp it! It’s in industrial consumerism’s nature not to convey how it depends on an army of the screwed…but degrowth is another argument (and yes this site did turn me on to Tverberg).

Just as we know exhaustive s-media dossiers/profiles can help algorithms figure out right now who to “restrict,” so also a whole horde of scaming scavenging “flexians” might eventually end up figuring out exactly who to take from. Until…if ideologies were racial in nature…things got pure enough for whatever phase of the [coherent appearing] orthodoxy settling out. Whichever one wins at musical chairs, Trumpian or Schiffian.

Something to do with Ellul’s technique and Kafka?

The western demos has lost much connection to geopolitical reality and scientific reality. I could go on about the former; but, re the other…when a [high art] means of conveying information has become the end, one can see that an avalanche of content of one kind or another could derail the whole thing? The Winston Smiths these days are like Whiteheadians telling us substance doesn’t matter because there is none…there are only the phones and Big Tech stocks.

I think we will have to bring psychology into all this. As state must separate itself from church + give it leeway, so onliners should do likewise vis a vis not-materialistic-determinists. Onliners in one sphere welcome somewhat Sheldrake and Islamic believers eg, but when it comes to how gov should govern they view such as non-relevant. It’s become too obvious. Alex Christoforou has made this point. Much of Russia feels this way. Of course, writers (vs “real” economy workers) get doctrinaire. Those who represent feelings in Russia [and speakers, Putin] say one thing; but I think, as Gessen (?) pointed out, there is an expectable/normal number of gays at the institution of the Kremlin (I know OTOH Gessen recognizes the faction there that would seek to scapegoat them).

Chris Hedges, ‘American Sadism’ https://www.mediasanctuary.org/event/chris-hedges-american-sadism/

the End State they imply as a desirable endeavor sounds great.

i could easily sell that in the feedstore parking lot….and to everyone but the actual owners of the place.

but it ain’t gonna happen until the fundamental premise is changed:

status seeking, like money, markets and current economic dogma, is not a thunderstorm, or some angry and capricious god.

it is also not a natural phenomenon, but a “thing of the people”(res publica)…we collectively create it…but that creation can be manipulated given enough resources and power and the perceived and ultimately pathological need to wield such power.

it is entirely possible for a person to eschew status seeking and keeping up with the joneses.

“Our desires and possessions are the strongest fetters of despotism”-Ed Gibbons

see also μηδὲν ἄγαν(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moderation)

but one must want to resist the all but omnipresent manipulative whispers(if not shouts—“Hit BY a TRUCK!???!”)

and, to make matters worse…if someone somehow manages to cultivate and attempt to live such a moral stance, there’s all the rest of those humans….mind glued to the whispering wurlitzer and it’s simultaneously overt and covert gospel:”I need a Boat!”

to go that way is to willingly become a heretic(gr: Choice Maker), if not a pariah.

again…One on One…Evangelism….

what else do we have?

Leisure, sure.

Abundance, now that depends on where you set your high water mark…

Isn’t something missing from their article? Is governments completely powerless to do anything and it is only through bargaining, either individual or through unions, that more time for leisure can be had?

Historically then once upon a time, when governments represented actual people instead of as now representing non-corporeal entites known as companies, then it was possible to legislate for reduction of working hours, paid vacation, paid parental leave, pensions etc.

I believe that if there were not such legislation already in place then some would say out loud that they believe (without even getting paid to say such things) that such legislation is impossible.

Legislation is at the very least a theoretical possibility but in practice then I suppose that now with the (best?) legislators that money can buy then it is impossible.

My recollection is that Keynes’s point was a relatively simple one. The technology was coming into existence to enable radical reductions in the working week if the political will existed to make that happen. He assumed it would, as did many people when I was young. We were wrong. The possibility still exists, but the political will is still lacking.

That’s because, as per neoliberal policy, it’s not enough to take s*>+, you have to eat it, too.

Perhaps the neoliberals are going to tame the antsy masses by taking away the abundance. However it seems dubious that they have any scheme at all other than “greed is good.” When Oliver Stone put it in his movie he thought he was creating mockery, not a road map.

> tame the antsy masses by taking away the abundance.

Maybe that will work in Europe; perhaps we will find out later this year.

In US? Making everything else scarce, creating a situation in which the only thing that is more abundant than needed is … small arms and ammunition? I can’t imagine that can be protective of the elites’ privileges and position.

Maybe they’ll migrate to Canada.

The “wealthy” have always had a strategy in dealing with “the unwashed masses.” It was, is, and will be, physical separation from the “masses” by living in “gated communities” and similar zones. Look at the exurbs surrounding most American cities. Then look at the police apparat and how and where it is deployed.

Mayberry USA is a revered piece of nostalgia because it is fictional. People know that it is “just a television show,” but still wish that they lived there. Thus are ‘they’ induced to ignore and depreciate the actual problems of their “real” neighbourhoods.

Then we have “Gangsta” and the “Thug Life.” Similar misdirection at play.

Stay safe.

Hey I have but a couple of fourscore miles to be at “Mount Pilot” (Pilot Mtn). Andy Griffith really did grow up in such a place if not named Mayberry.

Of course he left out all the bad racial bits….all the bad bits period.

This goes back to Rome. The senatorial class during the republic were oligarchics, but they competed with each other on who could put more back into the community via building, festivals, etc. Who had the most plebs on his rolls of support was a measuring stick. By the late empire, the senatorial class and non-senatorial rich had removed themselves from the public sphere, built estates on which to live which were more like feudal plantations than estate as in a country home. They didn’t notice the changes that would make the western empire collapse because it didn’t affect them. Until it did.

My observations based on the rats we have around our small farm is the people I know in the “rat race” work much harder than rats, much harder.

I agree completely that an expansion of “unconditional public services” would cure this overwhelming inequality we suffer – at least to the point that full equality will be an achievable long term goal and in the meantime there will be far less unnecessary suffering – possibly none.

yes, the problem is not doing the right thing with the “abundance”. which appears to be indulging the upper middle class and upper class.

for the rest of us, there is no apparent abundance. well, abundance of cheap and throwaway crap, but that’s a rant for another time.

as for the hours per worker, i guess i would have to see the actual methodology on this. our population is higher, women have more fully joined the workforce (they were always there, but expected to drop out as childrearing came to the fore in life and now are expected to drop the child at the daycare), and we essentially let tons of people in to work. more people are working as many hours as they can to earn that “get along income” of whatever percentage of the median it is right now (extremely subjective measure, sounds like).

telling people that the problem is that wealthier people tend to work more to increase their status is not going to make poor workaday schlubs trying to pay the mortgage, car note and water heater repair bill feel any better about life. and that seems to be the main point this writeup is getting at. the upper middle COULD HAVE HAD leisure while the lower ones “willingly drop out of the rat race” (who are they talking about? just because you don’t try to get your kid into Harvard doesn’t mean you can drop out of anything) but they choose to do something else with their time.

oh, and i don’t know if these economists know it, but the lower orders can’t get the hours they need or want quite often. they’d choose “more work” too, but for very different reasons. the hours they do work do not provide enough “get along income” and yet the structure of the workplace is such that corporations don’t want benefit-drawing employees and so overschedule a bunch of workers at 24 hrs/wk and continually churn through them. but this reality seems to be totally invisible in this article, instead explaining the “lower hours of the lower orders” as some kind of personal choice to deal with the fact that they are not going to ever earn what the PMC earn.

this all seems muddled. but that’s probably a reflection of the reader (me).

A large social science literature focuses on differences between, and causes of, the “natural growth” and “concerted cultivation” approaches to parenting.

Separately, among unionized workers, union contracts tend to dictate working hours, work rules, wages, benefits, etc. In the US, at least, government has typically assisted corporations’ drive to disempower unions.

So-called “primitive” peoples actually had more free time than most modern folks do, and thousands of years passed before clocks were invented…

Tim Ferriss ‘4 Hour Work Week’. the idea is to run a small buisness and automate as much as possible so you are not spending most of your time on maintenance but ‘only 4 hours a week’ so to speak. You use your working time for productive things, the creative parts of the work you care about. And then go on extended holidays while the buisness keeps running itself. Thats really what the book is about although its been highly misunderstood. So the book was/is wildly successful. I don’t know how practical or useful it has been for people. It apparently didn’t have a lot of original content. But it did heavily recommend outsourcing overseas as much possible. ‘Don’t feel bad, you are doing those offshore workers a favour’ . Considering how influential the author and his book are I can’t imagine that did favours for the US economy. A few years Ferriss relocated from San Francisco to Austin, Texas (US). Primarily based on his complaint that San Francisco was full of the superficial static of obsessive start-up culture and no quality engagement. (Oh and that his mates in the Pentagon had told him Silicon Valley was were the Islamic extremists were likely to strike – this is from a Reddit Q & A he did) The irony of his contribution to that culture was seemingly lost on him. I had always noted Ferris always seemed unable to type a paragraph without including a phrase like ‘tech stocks’ somewhere within it.