Yves here. This VoxEU post does a very solid job of trying to estimate the importance of Russian output to various commodity markets, and importantly Russia’s role in supply chains. However, even this piece misses some issues due to the impact of the conflict on Ukraine, and that Ukraine’s output profile has parallels to that of Russia.

Rev Kev pointed out recently that Russia has stooped to a bona-fide sanction (as opposed to its more passive-aggressive variants) with neon after the US and EU barred the export of semiconductors to Russia. As you can see from the video below, Ukraine had accounted for about 50% of the global output of neon via two plants, one in Mariupol and one in Odessa. That’s now off the market. Russia had 30% of the market, which is now 60% of what is left. And neon is essential for the lasers used to etch semiconductors. (Readers: does a laser keep using the same neon over its life, or does it need new neon periodically/often? That will make a big difference in terms of how quickly this restriction bites).

The speaker is sweeping in his claims about who shelled what in Mariupol. It’s clear that Ukraine was responsible directly and indirectly for attacks in residential areas; I’m not clear why Russia would have wanted to attack the neon facility but it might have been collateral damage when Azov retreated to the industrial part of town.

By Maria Grazia Attinasi, Economist in the External Developments Division of the European Central Bank; Rinalds Gerinovics, Analyst, ECB; Vanessa Gunnella, Senior Economist, ECB; Michele Mancini, Economist, Bank of Italy and ECB; and Luca Metelli, Economist, Bank of Italy (on leave at the ECB). Originally published at VoxEU

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions imposed on Russia are adding strains to already disrupted global supply chains. This column introduces a new indicator to show that the war is already rattling global supply chains. It also argues that despite the modest share of Russia and Ukraine in global trade, the ramifications for global activity can be sizeable as both countries are among the top global exporters of energy products and raw materials that enter upstream in the production processes of several manufactured goods and that may be hard to substitute in the short term.

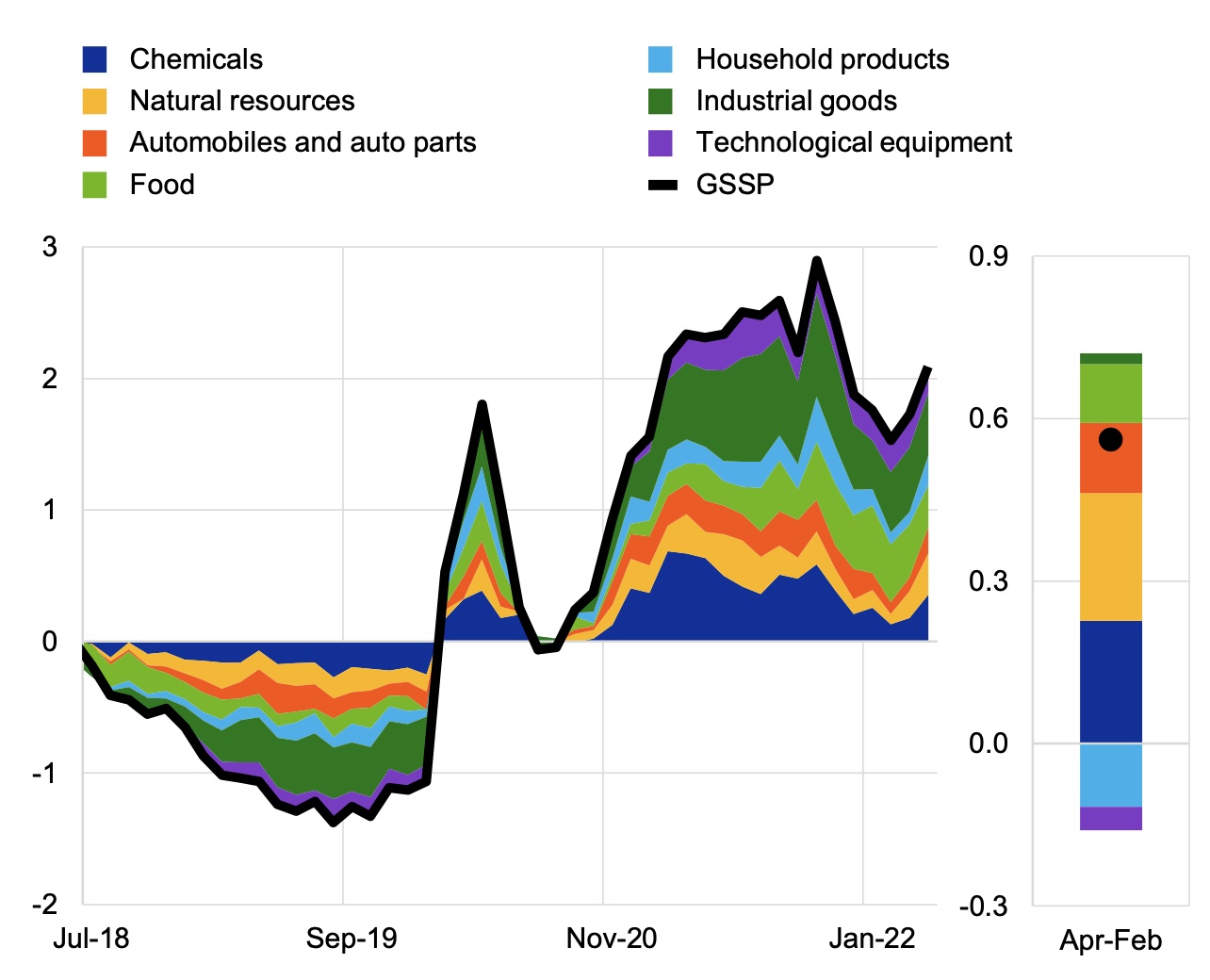

Supply bottlenecks have worsened since the onset of the war, especially in sectors largely dependent on Russia’s and Ukraine’s exports. We construct a new index of global sectoral supply chain pressures (GSSP) which disentangles the contributions of seven industries to aggregate supply pressures in the manufacturing sector. This indicator is derived from a vector auto-regression (VAR) with global purchasing managers’ index (PMI) variables such as: output, output prices, and the suppliers’ delivery times of seven manufacturing sectors. A global supply shock is identified through sign restrictions and the indicator is obtained bottom-up by aggregating the fluctuations in sectoral PMI suppliers’ delivery times (SDT) that are explained by the global supply shock.1 The GSSP indicator suggests that supply pressures intensified again since March (Figure 1), with the natural resources and chemical industries sectors being the main contributors. This pattern of sectoral disruptions likely reflects the impact of the war in Ukraine, as both Russia and Ukraine are important exporters of metals and mining products, as well as products used in the production of fertilizers (i.e. the chemicals sector).2 Such supply disruptions, not yet fully captured by available economic data, are likely to intensify in the next few months, especially in Europe.

Figure 1 Supply chain pressure indicator in global manufacturing

(standard deviations from the average value and point contributions)

Sources: IHS Markit and authors’ calculations. Latest observation: April 2022.

Notes: Left (right) hand side panel is aggregated at quarterly (monthly) frequency. Higher values of the indicator point to worsening in the supply chain pressures.

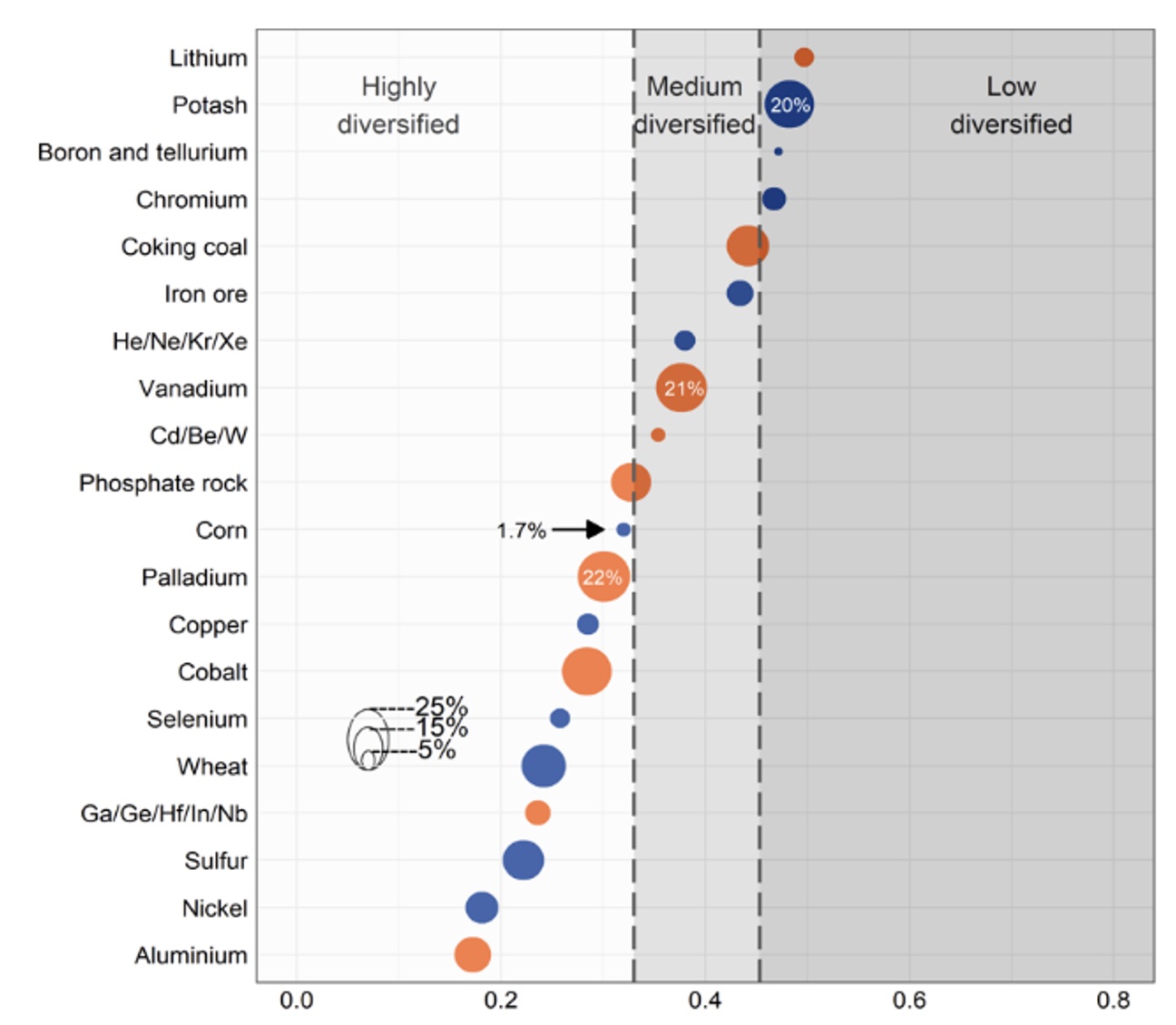

Figure 2 Russia’s share in global exports of raw materials and degree of export market concentration

(share in world’s exports; Herfindahl-Hirschman index; 2019)

Source: Trade Data Monitor, European Commission and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Materials marked with red circles denote strategic raw materials as defined by the European Commission’s latest criticality assessment (2020 Factsheets). The size of the bubbles refers to share of Russia in global exports.

Looking at Russia’s trade specialisation is useful to assess the potential implications of war-related disruptions for global supply chains and their geographical dimension. Russia’s exports of oil, gas, and coal account for 15% of the world’s exports of these commodities and the EU is its largest importer and the region with the highest import dependence from Russia. This explains the supply pressures emerging in the natural resources sector. In addition to energy commodities, Russia is also a key exporter of raw materials, including those classified by the European Commission (2020) as critical given their economic importance and high supply risks (Figure 2). For example, Russia exports materials used in the production of fertilisers, especially potash, where it has a dominant position, but also of sulphur and phosphate rocks. When looking at critical raw materials, Russia is a large exporter of palladium, vanadium, and cobalt, which are most prominently used in the production of 3D printing, drones, robotics industries, batteries, and semiconductors, thus affecting also other sectors, such as electronic appliances, transportation, and most prominently the car sector. Russia is also the fourth largest producer of coking coal, used for steel production, where it also enjoys a dominant market position, while Ukraine is one of the largest exporters of iron ore, which is used in iron and steel industries.

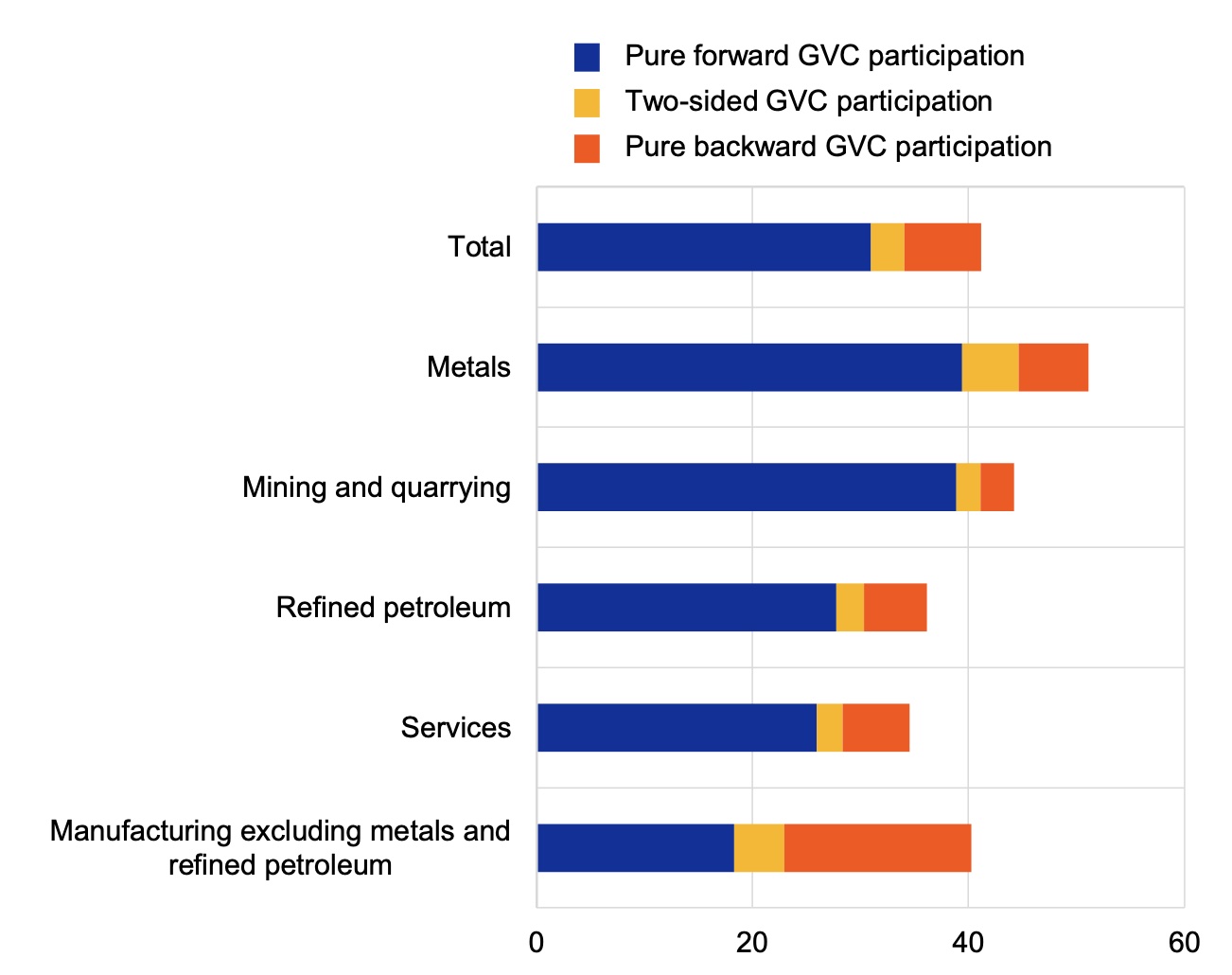

War-related disruptions to production and trade flows from Russia may be amplified through global production networks given the country’s significant forward integration in global value chains. Russia’s share in global forward global value chains participation is around double the size of its share in gross global trade (2.8% versus 1.5%). Notably, Russia has one of the highest forward participation rates in supply chains, as more than 30% of its exports consist of inputs used by its trade partners as intermediate inputs, compared to a global average of just 18% (Figure 3). This is explained by Russia’s specialisation in energy and metal industries, which are intrinsically more forward integrated, being positioned upstream in the production process. Therefore, disruptions to Russia’s exports might well propagate downstream through supply chain networks, having an impact also via the indirect trade (Winkler and Wuester 2022, Winkler et al. 2022). Moreover, as Russian inputs are involved in several stages of production, implications of disruptions could potentially be long-lasting, in line with previous firm-level empirical evidence based on the Tohoku earthquake (Boehm et al. 2019).

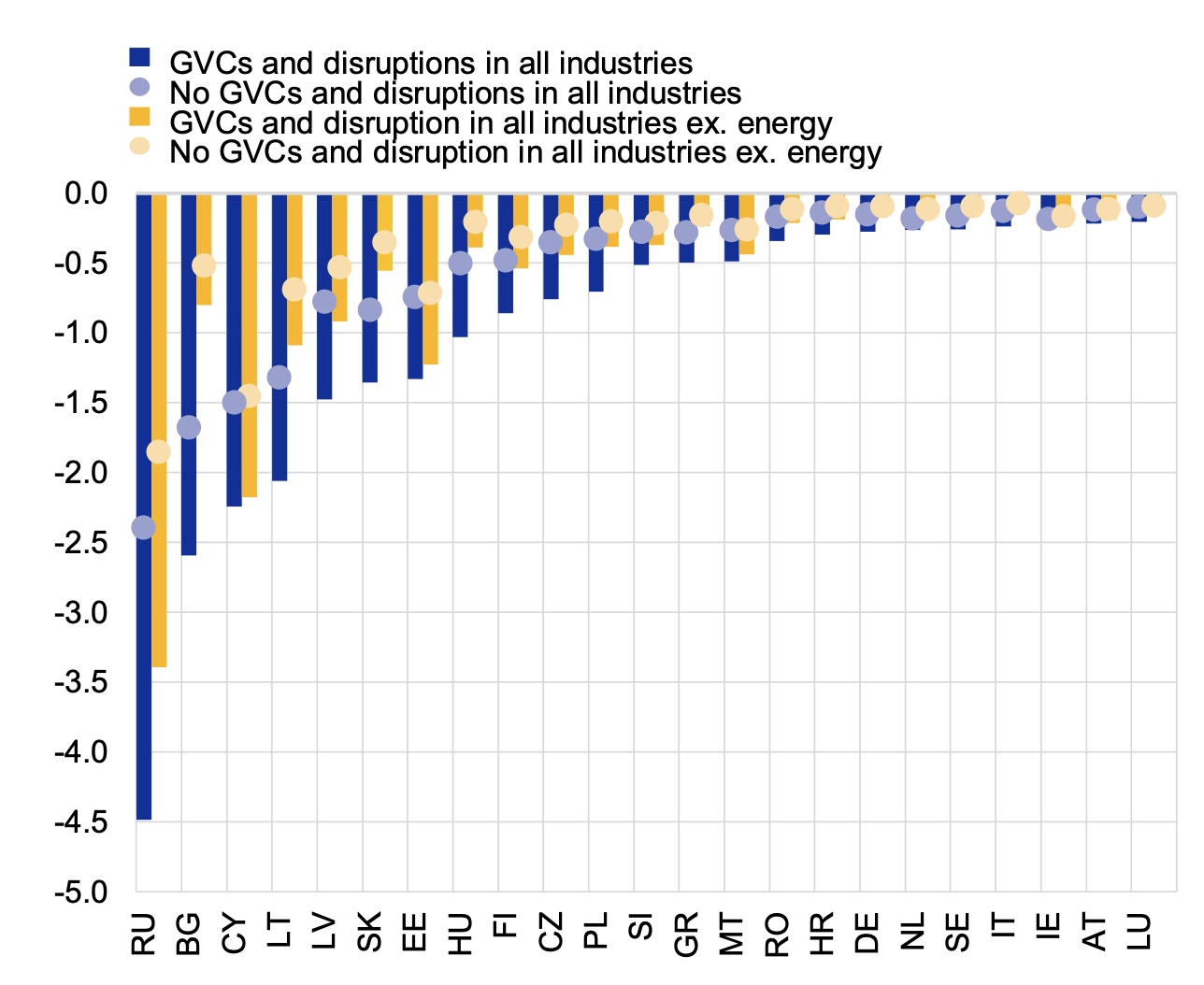

Quantitative trade models which account for global value chain linkages find that the size of the welfare effects of trade disruptions due to the war is double compared to standard models. In a recent work (Borin et al. 2022) a multi-sector, multi-country general equilibrium trade model (Antràs and Chor, 2018) is exploited to gauge to what extent supply chains may amplify the effects of the collapse in trade between Russia and its trading partners. A decline in Russian imports from sanctioning countries in line with the most recent trade data is obtained through an increase in bilateral trade barriers. The results suggest that Russia and some EU countries, most notably Central and Eastern European countries and Finland, would be affected disproportionally compared to others, with the welfare effects being significantly larger when sanctions on energy are assumed, suggesting a highly pervasive role for energy inputs in production (Figure 3). Indirect cross-country and cross-sectoral linkages effects act as a significant magnifier, as they double the size of the standard (i.e. non-global value chain) effects, especially for those countries which have tighter supply chain linkages with Russia. One caveat to these findings is that the quantitative trade model features a high degree of substitutability across inputs, a feature arguably unrealistic especially in the short run for critical inputs such as energy (Bachmann et al. 2022). Under lower but plausible degree of substitutability, Borin et al. (2022) show that the magnitude of the effects on economic activity of disruptions to trade in energy products would be higher than estimated above and, in the case of a full energy embargo, they would increase markedly and may reach 4% of GDP in the euro area.

Figure 3 Russia’s participation in global value chains across sectors by different modes

(percentage share of total exports, 2020)

Sources: World Bank WITS, ADB MRIO tables.

Notes: Measures are based on Borin et al. (2021).

Figure 4 Amplification effects of global value chains

(GDP changes, percentages)

Source: Borin et al. (2022).

Notes: The model with GVCs relies on a full input-output structure. The model without GVCs utilizes an altered input-output structure where trade in intermediate products is attributed to trade in final products. Data refers to 2018. Only countries where welfare changes are larger than 0.2% are reported.

_____________

1 The indicator is obtained by aggregating the fluctuations of the sectoral PMI delivery times which are due to the global supply shock. These sectoral fluctuations are weighted by the relevance of various sectors in the global economy. The indicator compares well with the indicator GSCPI produced by the NY Fed, sharing a high degree of correlation (around 90%). The sectors considered in the indicator are Chemicals, Natural resources, Automobiles & Auto parts, Food and Beverages, Household & Personal Use Products, Industrial goods, and Technological Equipment.

2 Our indicator likely picks up also the effects of the severe lockdown measures introduced in China since mid-March in response to the spread of the Omicron variant, and which caused disruptions to economic activity and logistics.

See original post for references

In a calculated war of attrition, brinksmanship, and PR jingoism, the entire range of pain, adversity, and hardship in the form of economic collateral damage has not yet been fully intellectually realized and that includes a multiplicity of ‘chance’ events that simply cannot be planned for, since future events and their entire range of outcomes and spillovers are not able to be perfectly predicted. So there is always the possibility of unforeseen additional grief being added to the already present adversity.

See for example,

“Natural gas prices surged across Europe on Thursday after a fire broke out at a key US export hub, putting further pressure on already tight global supply.”

“European natural gas prices soar by almost 40% after fire at key US export terminal”

https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/commodities/natural-gas-prices-lng-europe-texas-freeport-terminal-fire-2022-6

It is further assumed that some sort of ‘breaking point’ will be needed in order to move beyond the current impasse.

The trouble with global resources is you tend to think of them like pieces on a chess board. So when you see Neon being taken off the market, it is like seeing a knight being taken off a chessboard. But it is not like that at all. It is more like a Jenga tower. And yes, you can remove a fair number of pieces but take the wrong one out and down she comes. So you look at a problem in the supply chain and you try and work out the effects downstream as they work their way out. The west tells Russia no computer chips for you so Russia says no means to produce chips for you either. So trying to work out an arrangement may take months but in the meantime, a shortage of computer chips is now going to get much worse. Meanwhile here is a new problem to contend with in the supply chains – ‘An explosion in Texas has knocked out 20% of US LNG export capacity for at least three weeks’–

https://www.rt.com/business/556841-freeport-lng-explosion-exports/

I believe the term you are looking for is cascading failure. As someone working for a global manufacturer we just keep cascading. I used to think we needed a recession to sort out the supply chain but now I am beginning to think this stage of globalization is at a total deadend.

> Readers: does a laser keep using the same neon over its life, or does it need new neon periodically/often

I’ve been wondering about this since the first mentions of potential neon shortages after the beginning of the SMO. I can’t imagine that the neon “wears out” or that it leaks out. Being a noble gas, I would not expect it to react much with the vacuum vessel or internal metal. Perhaps other parts of the laser wear out and it is cheaper to replace than to repair. I suspect that the issue is manufacture of replacements or new equipment for new factories.

Per this item,

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/helium-neon-laser

helium/neon lasers do have a finite lifetime, so it may be that “new” neon is used in the manufacture of replacements for lasers that are at the end of their service life. The lifetime mentioned in the link is quite long, multiple years of continuous operation.

One would think that it would be possible to recycle the gas in decommissioned gas lasers, but that might be costly given that there is very little present in each laser (low pressure is required to reduce collisional de-excitations).

A neon shortage would also crimp production facilities expansion.

This item,

https://www.experimental-engineering.co.uk/helium-neon-lasers/he-ne-laser-tubes-heads-structure-power-requirements-lifetime/

suggests (toward the end of a long page) that the lifetime limiting thing is changes to the surface of the cathode inside the sealed tube. I would think it would be much cheaper to replace the laser tube than to try to repair something inside the sealed cavity, which would require opening it and then refilling after the repair.

If things get dire, perhaps they can start recycling neon from ‘end of useful life’ lasers.

This link gives the replacement regularly:

The link has a lot of good info on the physics behind the laser and a bit of info on the supply chain for the chips.

Well . . . . if there is no new neon coming onto the market, then they will just have to save the contaminated gas and re-purify the neon itself out of that gas, now won’t they? If they want to keep etching chips, that’s what they will have to do.

And if we want to keep having chips, we will pay the higher price involved to cover the higher cost of constant recycling of an unchanging/ non-growing stock of heirloom legacy neon. We will pay it and we will like it, as part of the higher price of even having chips at all.

But what percent of lasers are manufactured in the west? Anyway, I’m guessing the west has to buy some from the east; so, with Ukraine’s neon off the market, how much will that crimp the east’s roll out of semiconductors and/or lasers?

Lastly is there any kind of a precedent for, say, if Russia had put a quasi sanction (tax?) on natural gas until certain Aegis Ashore installations were removed? Or until some of our sanctions on Russia were removed?

Edit – just saw super extra’s post

Square miles matter- the more square miles a country has the better the chance it has of finding valuable minerals, fossil fuels and good agricultural land on or under the nation’s soil.

The ratio of land to population matters. The lower the population density the more extractable resources per person. There’s a reason Australia is called “the lucky country”. That’s why the US and the USSR were able to win WWII- lots of resources/person.

Big free trade areas matter. The US, the USSR and the British Empire had economies of scale because they had large areas, large resources and big populations- and their trade rules excluded competitors.

Now we have something called “free trade”- which isn’t free trade. Just ask someone trying to sell American software or high-tech in China, drill for oil in Saudi Arabia or send sugar to the US. Plus all the production still depends on valuable minerals, fuels and resources. Suddenly we’ve noticed that the world’s largest country, Russia, has a huge area, a low population density and lot of that stuff- and the Ukraine isn’t far behind. Duh… Plus neither country has the low-end, third world curse of a rapidly expanding population due to high birth rates or immigration lowering the resource/people ratio. The US now has 1/3 of the resources/person it did in 1941- and it shows.

The folks with a good resource/people ratio and large pools of natural resources can put up with high levels of pollution (located miles from the urban areas and dissipated over the large spaces) in order to produce first-stage manufactured goods from the natural resources. The Ukraine uses coal and no-pollution-control iron factories in Mariupol; the Russians do the same in Siberia, both with this nice byproduct called cheap neon to sell to people like us.

All Covid and the Ukraine War have done is kick open the ant hill so we can see how and by whom our iron, computer chips, natural gas and bulk chemicals are made. The roof is off the Factory. We can all look down and see the pollution in the Ukraine and the sweating people in the Chinese factories. All the nice places to live depend on them. We can’t pollute LA so we’ll we’ll fill up with gas from Midland, TX and Saudi Arabia- you know, low population density, high resource places- and with toys and trinkets from the high-density/low resource sweatshops in places like South Asia and China.

If we want some cheap neon all we have to do is let a few traditional, smoky, open-hearth iron makers reopen in Pittsburgh.

Yes, and any feasible transition to green prior was hardly even known. The ideas didn’t encompass details like this blog does. Maybe to go beyond Greens there should be HKSP, Hard Knocks School Party. Learn from the knocks. Greens trusted Fauci too much. And in Germany they must think Blinken and Sullivan makes sense? What have they learned from Covid and the war?

The latter is doomed. Some kind of planned transition to degrowth is what’s called for (Nordstream2’s already “grown,” and, if it’s not being used by the time the vortex dips again, possibly buku pipes’ll be a’bustn).

We need to start on what Alfred McCoy said might come in 2050. If too many westerners don’t know how to do something constructive, care giving might be a decent teacher (and we need caregivers). Once you’ve done it, probably you can do anything. I’ve done it, and I’ve done lots of other kinds of work. And really this is the path Cuba took (what’s the news on the protein sub unit jabs BTW?).

Meanwhile so many things just a cat’s whisker out of reach for us working stiffs. Like that substack on Bernard Charbonneau. Where’s the time to read it? Where’s the money? Where’s the dough?

Of course, something constructive on a mass scale (where it would make a difference) needs a big national pow wow and the dreaded…planning. The only thing I’d disagree with on the part of those out there now inclined to accept such [MMT people?] is…now is the moment where it has to be careful and right. There aren’t just enviro laws these days to stand in the way of WPA type projects (as Harold Meyerson has pointed out). There’s also a climate problem where we can’t afford to do anything but the best thing. For instance, speed rail. Are there enough people going somewhere important doing something important in this country to justify it at this juncture? Why not build up freight rail/depots? Why not have better bus surface (for workers in real economy) at train stops?

Any thoughts appreciated. Don’t know where Steve Grumbine stands on this exactly, but I thought he made good points starting at around 41:40 [for war intricacies re trials/verdicts, grain, mines, Erdogan, etc…Mark Sleboda was on prior to Grumbine] https://rumble.com/v17zz5o-inflation-40-year-high-water-and-national-security-egbert-v.-boule-ruling-a.html

Neon production is typically a byproduct of large scale steel production. So it may well have been a byproduct of the destruction of the Azovstal plant.

I can’t get beyond how poorly designed each and every single one of those charts is. I suggest all the authors take a close look at Tufte’s “The Visual Display of Quantitative Information” so that their analysis is actually communicated clearly.

Glad to learn I wasn’t the only one who had trouble making sense of them. They made me feel stoopid.

Being made to feel stoopid is par for the course. And I’m not a player of golf.

Exactly so. The meanings of each are hard to comprehend, and made more so by a lack of accompanying textual explanation. Tufte is your man for improvement, but I imagine most graphics people now have never heard of the book.

The concept that neon is a byproduct of steel manufacturing is misleading. In the present case of Russia, it may appear so. But an understanding of how Russia has come to obtain this leverage (in its campaign of agression against Ukraine) is best understood by reciting the history of the industrial gas business in the former USSR ( that Russia invariably inherited after the collapse of the former Soviet Union) . Steel was indeed a major segment of the former Soviet economy, and, it required a significant investment in large air separation plants to produce the oxygen gas needed in steel manufacturing. During the same time frame, the USSR would not have access to western specialty gases markets to be able to buy the CRITICAL MATERIALS ( like rare gases! ) that were necessary for the development and construction of Soviet military , aerospace, and research programs . The central commmittee therefore established state-run air separation plants MUST be desiged and constructed to recover rare gases. This lead to a proliferation of air separation plants with a significant total Soviet rare gases manufacturing capacity . The necessary refining facilites for purifying the raw /crude neon by-product streams colected from state run air separation plants could then be centrally-located in both Russia and Ukraine. As such, it is a coincidence that neon has become associated with Soviet/Russian steel production. In fact, any large air separation plant COULD be initially-designed for neon recovery. However, of the subtstantial number of such large air separations plants that currently exist in western nations, China, and India , only a small number of these were initally designed WITH neon recovery systems . The main reason: the decision to install neon has little to do with the original purpose of building those air separaton plants . All major air separation plants typically service one or more industrial users in a locale. Some of these plants may also be tied into pipeline systems that may service a number of clients over a defined geographic region. Neon has therefore been a co-product of air separation ONLY when there has been interest by the plant owner to manufacture neon gases that it can market through that companies specialty gases portfolio. Under this business model, there has been little pressure or demand on western industrial gas companies to develop a “neon infrastructure for the semi conductor business”. It seems that semi conductor companies have also been comfortable with the current arrangment for some time, as they did not take a leadership role to develop a robust, relaible neon supply chain. The semi conductor companies did not understand the fragility of their neon supply chain; the current situaiton shows that no consideration has been made to have backup supply in the form of excess capacity, redundant plants, and ways to contend with geo poliltical disruption. In moving forward, the method for retrofitting rare gas recovery to existing air separation plants must be evaluated. Retrofit for neon however is certinaly MUCH MORE costly than constructing new air separation plants with neon recovery capabilty built into the design. But, it will be a much larger undertaking to build a sufficient number of new air separation plants neccessary to close the neon supply chain gaps, in the time alloted. Therefore, retrofit for neon to existing cryogenic air separaton plants must be seriously studied, and the cost impacts incurred therein will have to be assumed in the neon product costs. There have been some studies done previously that have opined that such approaches are “prohibitely expensive”. A world without an adequate supply of a critical material availbe to free markets may yet change some minds on what is “prohibitive”.