Yves here. I was going to take a stab at writing a post on the drivers of our current inflation, since contrary to a lot of conventional wisdom, the main causes are various forms of damage done by Covid that resulted in a marked fall in the productive capacity of the economy, then turbo-charged by sanctions blowback raising commodities prices. However, this tour de force by Servaas Storm give a far more comprehensive and data-driven take-down than I could ever hope to undertake.

Now admittedly, we’ve discussed many of the issues that Storm addresses, albeit separately. One is the ongoing labor shortage. Covid led some to not come back to badly-paid, high contagion workplaces. Some realized they could get by on one or one and a half income(s) rather than two after they ditched the costs related to having a two earner household with kids or had employer that let them work from cheaper locales. Some had to quit or go to part time employment due to long Covid.

And then we have the many and still not resolved supply chain issues. For instance, talk to anyone who has the misfortune to need to get household appliances. The sweet spot of pretty good but not deluxe has very long lead times.

Before you try saying, “Oh, but this is really just the result of too much money printing/government spending,” consider an similar argument similar to another one of Storm’s from Julius Krein in Unherd. Remember that one cause of inflation that was anticipated to be largely transitory was the increase in gas prices in 2021. Oil producers had been whipsawed by the Covid-lockdown and continued-pre-vaccine precautions killing car and air travel. In 2021, when demand picked back up, they had trouble increasing production quickly enough, generating sudden gas price increases. As Krein pointed out:

The most intriguing and potentially alarming trends are visible in the oil market. In December 2019, before Covid, global oil consumption was about 100 million barrels per day, and the price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude hovered around $50-$60 per barrel. At that time, the US operating rig count was around 800 (around 2,000 globally), according to Baker Hughes. After the pandemic hit, in 2020, global oil demand fell to about 90 million barrels per day, prices collapsed and briefly went negative, and the US rig count hit a low of around 250. Oil demand recovered about half the lost ground in 2021 and is expected to return to 2019 levels of 100 million barrels per day this year. In December of 2021, WTI spot prices were around $75, rose significantly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and currently sit around $110. Yet the US rig count is still around 700 (of 1,600 globally). The last time oil prices were above $100, before the crash of 2014, the rig count was over 1,800 (3,600 globally).

This trajectory is difficult to square with inflation accounts based on excessive demand. Oil demand has still not exceeded pre-pandemic levels; it is supply that has lagged. Meanwhile, far from being “too greedy”, companies seem to not be greedy enough — at least in the conventional sense of maximising profits. Instead of reinvesting their earnings in drilling new wells, even at profitable oil prices, companies have returned cash to shareholders.

Some have argued that oil companies are not drilling because of the Biden administration’s environmental regulations. As a critic of those policies, I am sympathetic, but they cannot account for the larger phenomenon, including international drilling. Others have suggested that ESG investing requirements have prevented the oil and gas industry from accessing capital. While there is no question that ESG as presently constructed is a disaster, this does not explain why companies are not reinvesting their own earnings. There are some time-lag issues — wells cannot be drilled overnight — but prices have now been elevated for months. Oil futures are also over $80 through most of 2024, meaning companies can hedge future production.

The best explanation is, therefore, the simplest one: shareholders prefer that companies return cash rather than invest, a preference widely discussed among industry participants and observers….

Fears of stagflation have focused on a Seventies-style wage-price spiral, but the above considerations suggest that a greater concern today may be the threat of a “profit-price” spiral. In the Seventies, investment was discouraged by high taxes, strong unions (which directed profits to labour), and relatively robust antitrust enforcement. With low investment, increasing demand only led to more inflation rather than growth.

Today, we have low taxes, weak unions (although tight labour markets), and high industry concentration. These conditions, combined with shifts in corporate governance and financial management, have also discouraged investment — by facilitating extractive financial engineering, as in the case of the oil industry example. A scenario in which companies maintain returns in a stagnant economy by preserving margins while avoiding competitive investment is also more consistent with recent empirical findings. Corporate profit margins achieved a record in 2021 (though they seem poised to retreat somewhat in the coming quarters), and studies have found that rising corporate profits have contributed significantly more to inflation than labour costs.

Note that your humble blogger was early to identify corporate disinvestment in The Incredible Shrinking Corporation in the Conference Board’s magazine. But I didn’t recognize how strong a role it was playing in our current economic tsuris.

This is a long but highly readable paper, so I hope you can find the time to do it justice. Of necessity, it carefully presents the views of various Serious Economists before taking them apart.

By Servaas Storm, Senior Lecturer of Economics, Delft University of Technology. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

A Specter Is Haunting the US—The Specter of Stagflation

Financial Times’ Martin Wolf (2022)is the latest influential voice sounding the alarm bell on ‘the threat of stagflation’ and calling for the Fed to drastically raise interest rates to bring inflation down to its target level. Published on May 24, Wolf’s diagnosis of where the stagflation in the US economy is coming from reflects current establishment opinion: nominal demand, fuelled by over-expansionary fiscal and monetary policies during the COVID-19 crisis, is exceeding US supply. To bring down inflation, these macroeconomic policy errors need to be corrected convincingly and as soon as possible. This is how Wolf puts it:

US supply is constrained above all by overfull employment […] Meanwhile, nominal demand has been expanding at a torrid pace. [….] The combination of fiscal and monetary policies implemented in 2020 and 2021 ignited an inflationary fire. The belief that these flames will go out with a modest move in interest rates and no rise in unemployment is far too optimistic. Suppose, then, that this grim perspective is correct. Then inflation will fall, but maybe only to 4 per cent or so. Higher inflation would become a new normal. The Fed would then need to act again or have to abandon its target, destabilising expectations and losing credibility. This would be a stagflation cycle — a result of the interaction of shocks with mistakes made by fiscal and monetary policymakers. (italics added)

Wolf hedges his bets and does not state how strongly the Fed should raise the interest rate in order to avoid the ‘grim’ prospect of a stagflation cycle. Wolf is in the good company of Lawrence Summerswho voiced similar concerns already in February. Summers, however, does not hesitate to provide more explicit guidance to monetary policy-makers in the Fed:

[….] we’re likely to have a need for nominal interest rates, basic Fed interest rates, to rise to the 4 percent to 5 percent range over the next couple of years. If they don’t do that, I think we’ll get higher inflation. And then over time, it will be necessary for them to get to still higher levels and cause even greater dislocations (Klein 2022).

Summers’ and Wolf’s calls for action are echoed by many observers in the financial sector. Mohamed El-Erian (2022), for instance, argues that

Also similar to the 1970s, the US Federal Reserve [….] is already dealing with self-inflicted damage to its inflation-fighting credibility. With that comes the likelihood of de-anchored inflationary expectations, the absence of good monetary policy options, and a stark choice for the Fed between enabling above-target inflation well into 2023 or pushing the economy into recession. (italics added)

Goldman Sachs Group President John Waldron has just one piece of advice for the Fed: “…. bring back Paul Volcker” (Natarajan and Reyes 2022). Wolf, Summers, El-Erian, and Waldron are thus putting serious pressure on the Fed to hike up interest rates more strongly and quickly than it is already doing.

On March 16, 2022, the Fed raised the interest rate by a quarter percentage point, from 0.25% to 0.5%—the first interest rate increase since 2018. And on May 3, 2022, it raised its benchmark rate by another half-a-percentage point. “We have to reassure people we are going to defend our inflation target and we are going to get inflation back to 2%,” St. Louis Federal ReservePresident James Bullard stated recently, adding that “our credibility is on the line here” (Egan 2022). Bullard doubled down on his view by recommending that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) should shoot for a policy rate above 3% this year.

Not only the Fed, but central banks all over the globe are raising rates rapidly in the most widespread tightening of monetary policy for more than two decades, according to a recent Financial Timesanalysis (Romei 2022). To bring down inflationary pressures, central bankers worldwide have announced more than 60 increases in current key interest rates in the past three months. The recent increases are just the beginning of a global monetary tightening cycle (UNCTAD 2022). The Fed, pushed by the likes of Summers, Wolf, El-Erian, and Waldron, is expected to move to a policy rate around 2.5%-2.75% by the end of 2022, but statements in the minutes of the FOMC indicate that its members are prepared to raise interest rates more, if and when deemed necessary.

A Soft Versus a Hard Landing

Few doubt that the monetary tightening by the Fed will push the US economy into a recession. This means there is no free lunch: bringing inflation down comes with a considerable societal cost. Opinions are divided over how deep and long-lasting this recession will be. Establishment opinion is that “the time to throttle an inflationary upsurge is at its beginning, when expectations are still on the policymakers’ side,” as Wolf (2022) puts it. That is, the sooner and the more aggressive the Fed acts, the lower will be the collateral damage to the US economy and the more likely the US economy will experience a ‘soft landing’—which is Central Banker Speakfor a relatively mild recession.

Channeling former Fed chair Paul Volcker, who has posthumously acquired a near-saintly status with the monetary policy commentariat, Summers adds that the cost of sharply increasing the interest rate to kill off inflation will be temporaryincreases in unemployment—and he opines that bearing this non-trivial (but temporary) social cost will be preferable to suffering from the permanent cost of inaction, which he predicts, rather ominously, will involve “stagflation and the associated loss of public confidence in our country” (Klein 2022). For Summers, a ‘hard landing’, a cherished euphemism for a deeper, bruising, recession, appears to be preferable to the long-run societal cost of a scenario in which the Fed does not act strongly and quickly enough, loses its inflation-fighting credibility, and cannot prevent the de-anchoring of expectations. Wolf concurs (again) and adds that “the political ramifications [of such a stagflation cycle] are disturbing, especially given a vast oversupply of crazy populists.”

The arguments of Summers and Wolf are fairly typical of the much broader macroeconomic debate within a select in-crowd of Very Serious Economistsover how to respond to the recent surge in US inflation. The tone of this debate in newspapers and online fora is dire (“stagflation, after all, is a grim threat”); the arguments are abstract (“monetary tightening is crucial to maintain the Fed’s inflation-fighting credibility and keep inflation expectations anchored”); the analyses are surprisingly ahistorical (“today’s situation is a repeat of the 1970s” and “bring back Volcker”), the discussions are relatively tone-deaf to the very inegalitarian negative impacts of the sharp increases in interest rates, the (social engineering) policy solutions are mechanical and actionable (“raise interest rates to 5% and the inflation will go away”); and the underlying thinking remains firmly within the box of establishment macroeconomics (“the Fed is capable of controlling inflation without killing the economy in so doing”).

A more acute assessment would recognize that interest rates are a socially very costly tool to ‘control’ inflation—especially when the sources of the inflationary surge lie in an unprecedented constellation of (mostly) supply-side bottlenecks which are driving up prices. Similarly, a close look at the past record of monetary tightening shows that the Fed has hardly ever managed to guide the economy to a soft landing with interest rate increases.[1]A key reason is that small interest rate hikes do not reduce inflation (at all). It takes large interest rate hikes, but those come with massive collateral damage to the real economy—and this collateral damage might well be larger than the damage done by allowing inflation to remain high for some, while actively managing its consequences (especially in terms of the distribution of incomes). John Cochrane (2022, p. 9) sums it up rather well:

The Fed likes to say it has “the tools” to contain inflation, but never dares to say just what those tools are. In recent U.S. historical experience, the Fed’s tool is to replay 1980: 20 percent interest rates, a bruising recession hurting the disadvantaged especially, and the medicine applied for as long as it takes. Will our Fed really do that? Will our Congress let our Fed do that? Can you deter an enemy without revealing what’s in your arsenal and whether you will use it?

There are reasons to believe that the collateral damage wrought by substantially higher interest rates will be even higher today than in 1980. The key point is that more than a decade of extraordinarily low interest rates have led to a significant increase in corporate and public debts and an unsustainable bout of asset price inflation in the housing market, the stock market, and almost all other financial markets. A large interest rate hike will create a financial crash. The Federal Reserve (2022) recognizes these non-negligible downward risks of monetary tightening to the American economy in its Financial Stability Reportof May 2022. Bringing back Volcker might, therefore, not be a good idea. What is to be done?

A New INET Working Paper on US Inflation

In a new Working Paper for INET, I attempt to recover the lost plot, arguing that the recent inflation has mostly supply-side origins, caused by the COVID-19 crisis and the Ukraine war, and has been enabled by mistaken past and current macroeconomic policy choices. The paper takes a close look at the current inflation in the US, showing that it is not due to a generalized co-movement of (all) prices, but to a number of sector-specific price increases in industries strongly affected by global commodity-chain disruptions (Section 2). The corona crisis has been seriously stress-testing the resilience of the global supply chains that have developed during three decades of neoliberal globalization—and the system has been found wanting. Section 3considers the global supply side of US inflation in more detail and investigates how global supply chain disruptions and higher global commodity prices have raised US import prices; I find that higher import inflation has been directly responsible for almost one-third of the increase in the PCE inflation rate during 2021-2022.

Section 4presents data on accelerating inflation in the rest of the world. These data underline the fact that the rise in US inflation is by no means exceptional: almost all other economies are experiencing similar surges in (consumer price) inflation as the US. Inflation is running well above central bank inflation targets in all advanced economies. In most, central banks have so far reacted to the increase in inflationary pressures with a gradual response, tapering off unconventional monetary policy support introduced during the pandemic and raising policy rates. Interestingly, differences in the magnitude of fiscal relief responses to the corona-crisis between countries are not showing up in (statistically significant) differences in CPI inflation rates. This suggests that fiscal policy is not a key driver of inflation (differences).

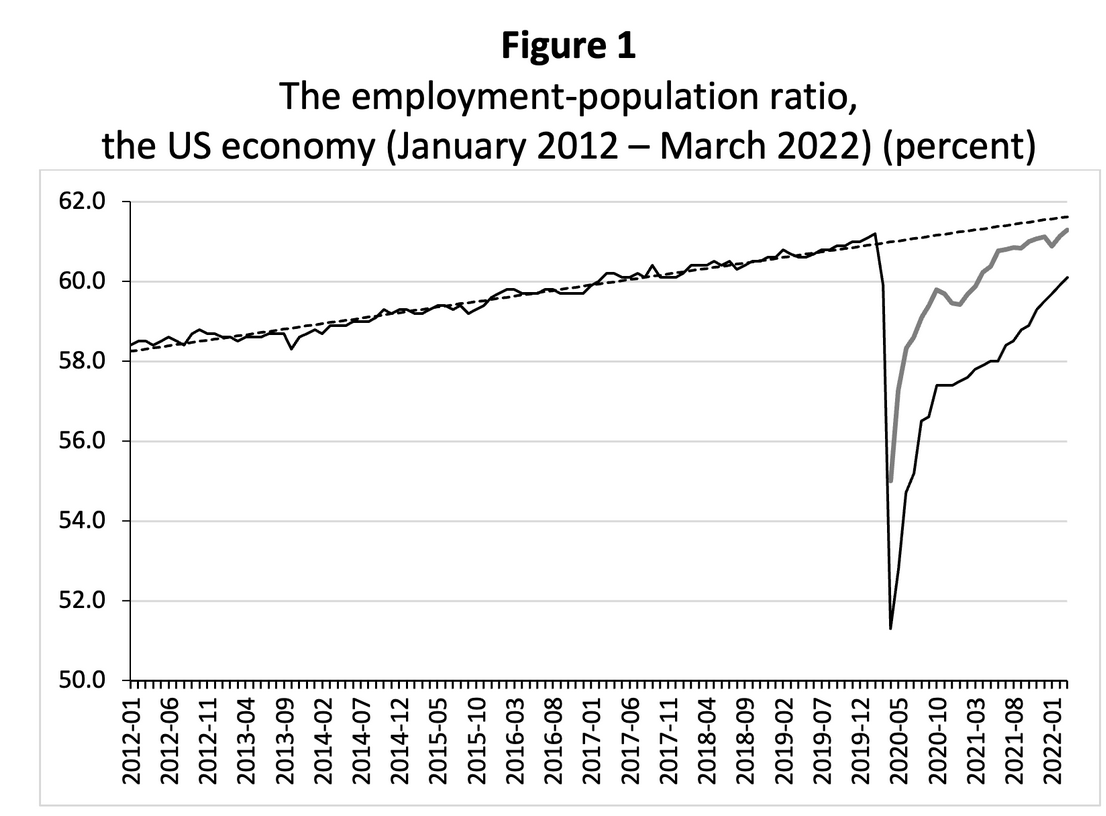

The impacts of the global supply shock were amplified by supply-side bottlenecks withinthe US economy (Section 5), including inefficiencies in US ports and a shortage of long-haul truck drivers. However, the most important domestic supply constraint triggered by COVID-19 arose from the sharp decline in the (effective) labor force of the US: the employment-population ratio declined by 9 percentage points in early 2020 (Figure 1). The employment-population ratio steadily increased from 58.4% in January 2012 to 61.2% in February 2020, but it sharply dropped to 51.3% in April 2020 and 52.8% in May 2020 in response to the arrival of SARS-Cov-2 in the US. The average monthly employment shortfall was around 8 million persons in 2021.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics. Notes: The dashed line is the counterfactual in which it is assumed that the employment-population ratio continues to grow at its trend rate (during January 2012-January 2020). Population is the civilian non-institutional population, i.e., people 16 years of age and older who are not inmates of institutions (penal, mental facilities, homes for the aged), and who are not on active duty in the Armed Forces. The employment shortfall in March 2022 (relative to the counterfactual) is 4 million workers. The grey line indicates the decline in the employment-population ratio due to “persons not in the labor force, who did not look for a job in the last 4 weeks because of the coronavirus pandemic”.

Even though the employment-population ratio climbed up again to 60.1% in March 2022, it continues to remain below what it would have been without the COVID-19 shock. The estimated employment shortfall in March 2022 is 4 million workers (relative to the counterfactual). As elaborated in the paper, BLS data show that during the period May-December 2020, more than 40% of the estimated employment shortfall was caused by “persons not in the labor force, who did not look for a job in the last 4 weeks because of the coronavirus pandemic”. In 2021, around 28% of the employment shortfall must be attributed to persons dropping out of the labor force because of the coronavirus pandemic.

For many workers, the coronavirus outbreak was the main reason for quitting a job—directly, because doing the job had a high risk of getting infected, but also indirectly, because the job offered no or insufficient health insurance, lacked the flexibility to choose when to put in one’s hours, did not allow for working remotely, or did not offer adequate child care support. In Spring 2022, there are still around 1 million “persons not in the labor force, who did not look for a job in the last 4 weeks because of the coronavirus pandemic”, and around 3 million workers decided to retire (temporarily or permanently), primarily because of COVID-19.

As a result, in March 2022, the US labor force still has 4 million fewer workers than in the ‘no-corona’ counterfactual. The sharp decline in the effective labor force has led to a tightnessof the US labor market which is showing up in a high vacancy ratio. As millions of workers disengaged from the labor force, by quitting or retiring, the number of job vacancies has risen sharply. The vacancy ratio, the ratio of job vacancies to official unemployment, has increased to 1.94 jobs per unemployed worker in March 2022, which is more than three times its long-run average level. This is what Martin Wolf means when he argues that “US supply is constrained above all by overfull employment.” But overfull employment is caused by the COVID-19 caused drop in the effective labor force of the US. It follows that, as long as COVID-19 continues to pose a significant health risk, the US labor market will remain ‘tight’.

Is There a Wage-Price Spiral?

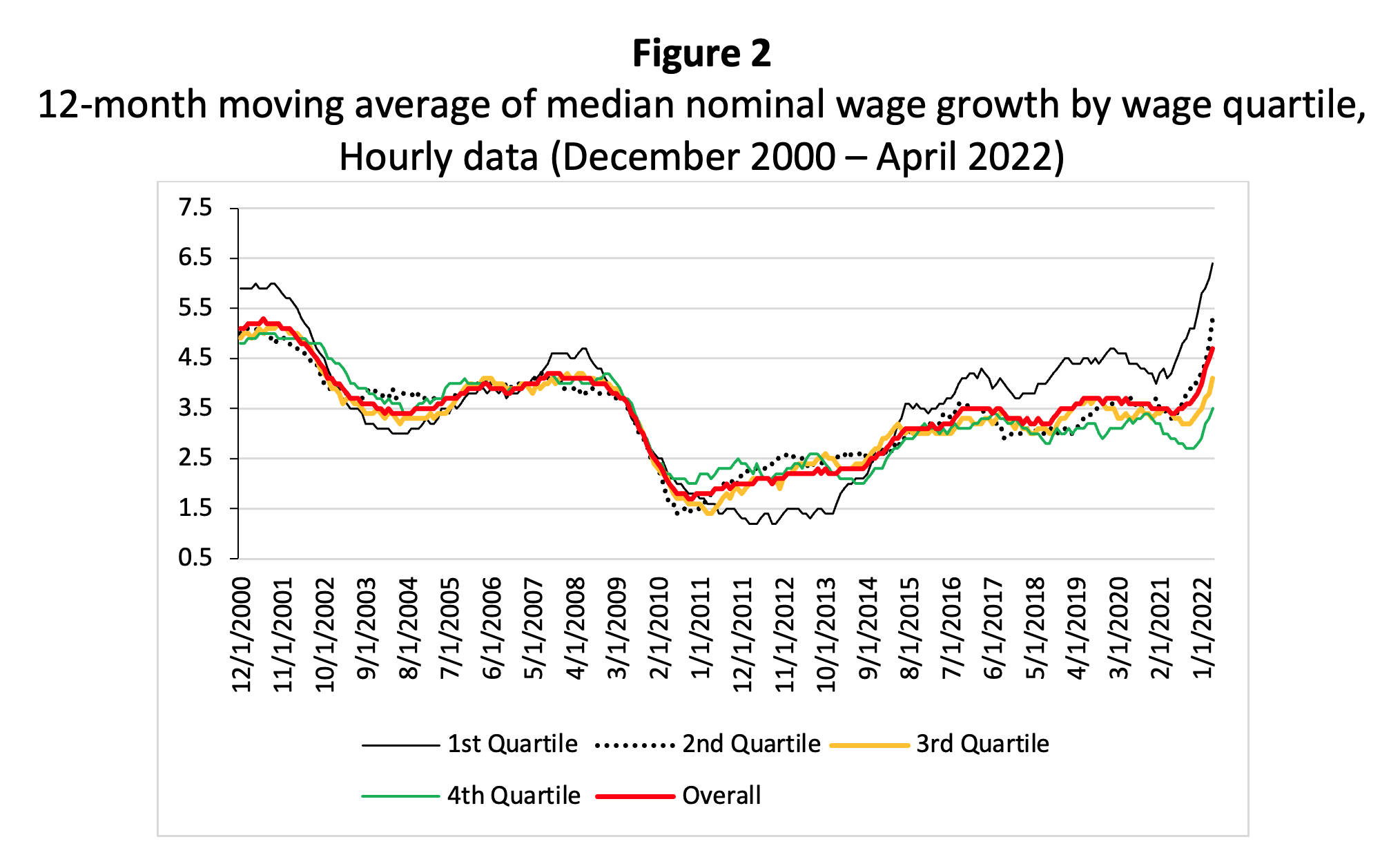

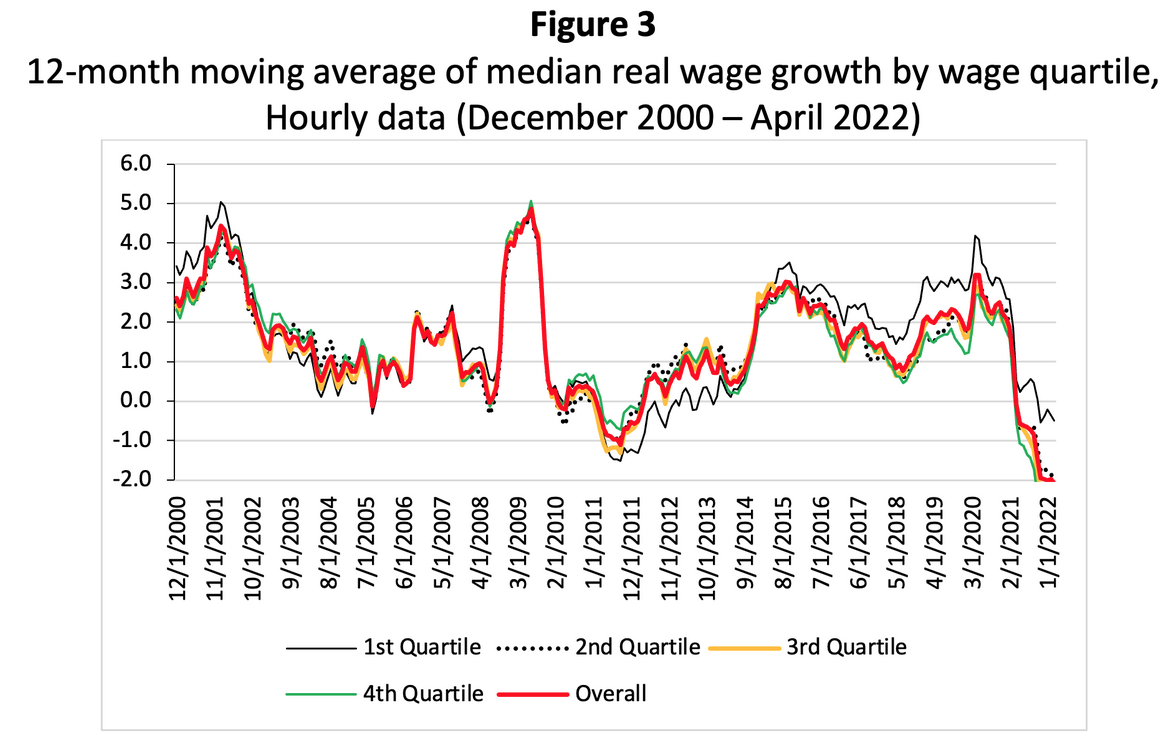

According to Wolf, Summers, and many other observers, US inflation is significantly driven by a wage-price spiral. The empirical case in support of this claim has been made by Domash and Summers (2022a, 2022b, 2022c) who argue that the vacancy and quit rates currently experienced in the US correspond to a degree of labor market tightness previously associated with below-2% unemployment rates. Such tightness, they warn, will make for “extremelyrapid growth in nominal wages” (Domash and Summers 2022a, p. 32). Specifically, “nominal wage growth […] is projected to increase dramaticallyover the next two years, surpassing 6% wage inflation by 2023 ….” (p. 21). This is serious stuff—notice the use of the words “extremely” and “dramatically” in these sentences. So, what is the evidence on nominal wage growth and its impact on US inflation? In response to the tightness of the labor market, nominal wages for the median US worker increased by 4.7% during April 2021 and April 2022 (Figure 2). This may look like relatively good news for US workers, whose median nominal wages increased by around 2.7% per year during 2010-2019 and whose real wages rose by only 1.1% per annum over the same period, but on a closer look, it isn’t. Nominal wage growth of American workers is not keeping up with accelerating PCE inflation, and hence, median real wage growth in the US became negative already in April 2021 (Figure 3). One year later, in April 2022, annual median real wage growth in the US is -2.1%. Real wage growth has been negative in almost all industries and occupations.

Sources: Current Population Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Calculations. See https://www.frbatlanta/chcs/wage-growth-tracker

Sources: Current Population Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Calculations. See https://www.frbatlanta/chcs/wage-growth-tracker. Nominal wage growth was deflated using the 12-month growth in the PCE price index (FRED series PCEPI_PC1).

In Section 6of the Working Paper, I identify various reasons why the evidentiary base of Domash and Summers’ (2022a) claim is not robust enough to substantiate their claim that the US is experiencing a wage-price spiral. A key point is that Domash and Summers assume that higher inflation is pushing up nominal wage growth. However, their own regression results show that inflation indexation is far from perfect: in 14 out of 21 regressions, the coefficient of lagged inflation on nominal wage growth in the US is notstatistically significant. This means that in two-thirds of their regressions, higher prices are found to reduce real wage one-for-one. In the remaining 7 regressions, the coefficient of lagged inflation on nominal wage growth takes an average value of 0.35. Hence, even when US labor markets are extremely tight, US workers are unable to protect their real wages—as their nominal wages grow only one-third as fast as the general price level. Higher inflation is extremely costly to workers, therefore. To single out higher nominal wages as a main causeof the increase in US inflation is not just incorrect, because wage growth barely manages to partially follow(not leading) inflation, but it is quite a stark example of blaming the victim.

Finally, I estimate a more complete econometric model which also includes supply-side constraints (in addition to the vacancy ratio). The estimation results suggest that, on average, 20.5% of (rising) PCE inflation can be attributed to the (rising) vacancy ratio (as a proxy of labor market tightness). However, global commodity prices and capacity utilization play more prominent roles and account for 67% and 35% of PCE inflation. Hence, labor market tightness does contribute to US inflation indeed, but supply-side constraints play a more important role. Besides, the labor market tightness itself is caused by the fact that labor demand has recovered more quickly than the effective labor force (as I discuss below).

The Problem That Shall Not Be Named: Profit-Driven Inflation

US inflation is also being driven by the pricing power and higher profits of corporations—a claim that Lawrence Summers rejected on Twitter as a form of ‘science denial’. But there is more than just anecdotal evidence that corporations with pricing power are using the current inflationary environment as a pretext to raise prices more than necessary because they do not have competitors to drive them to keep prices down. For instance, Fed economists Amiti et al. (2021) highlight the importance of (what they call) the strategic complementarity channel,which captures how much US firms adjust their prices in response to changes in the prices charged by their foreign competitors. To illustrate, if the price of imported cars increases, domestic car producers can also increase their prices. The strategic complementarity channel has been estimated to account for circa 30 percent of the effect of higher import prices on US inflation (Amiti et al. 2021).

The strategic complementarity channeldoes help to explain the profiteering by large US corporations which have been able to raise their profit margins to the highest level in 70 years. Nominal growth of corporate profits (by 35%) during 2021 has vastly outstripped nominal increases in the compensation of employees (10%) as well as the PCE inflation rate (6.1%). Using inflation as an excuse and helped by algorithmic pricing and AI, mega-corporations are choosing to raise prices to increase their profit margins – and they hold enough market power to do so without fear of losing customers to other competitors.

Corporate profiteering is contributing to the inflation problem. According to The Wall Street Journal,nearly two out of threeof the biggest US publicly traded companies had larger profit margins this year than they did in 2019, prior to the pandemic (Broughton and Francis 2021). Nearly 100 of these corporations did report profits in 2021 that are 50 percent above profit margins from 2019. Evidence from corporate earnings calls shows that CEOs are boasting about their “pricing power,” meaning the ability to raise prices without losing customers (Groundwork Collaborative 2022; Perkins 2022). Even the Chair of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, has weighed in on this issue, stating that large corporations with near-monopolistic market power are “raising prices because they can.”

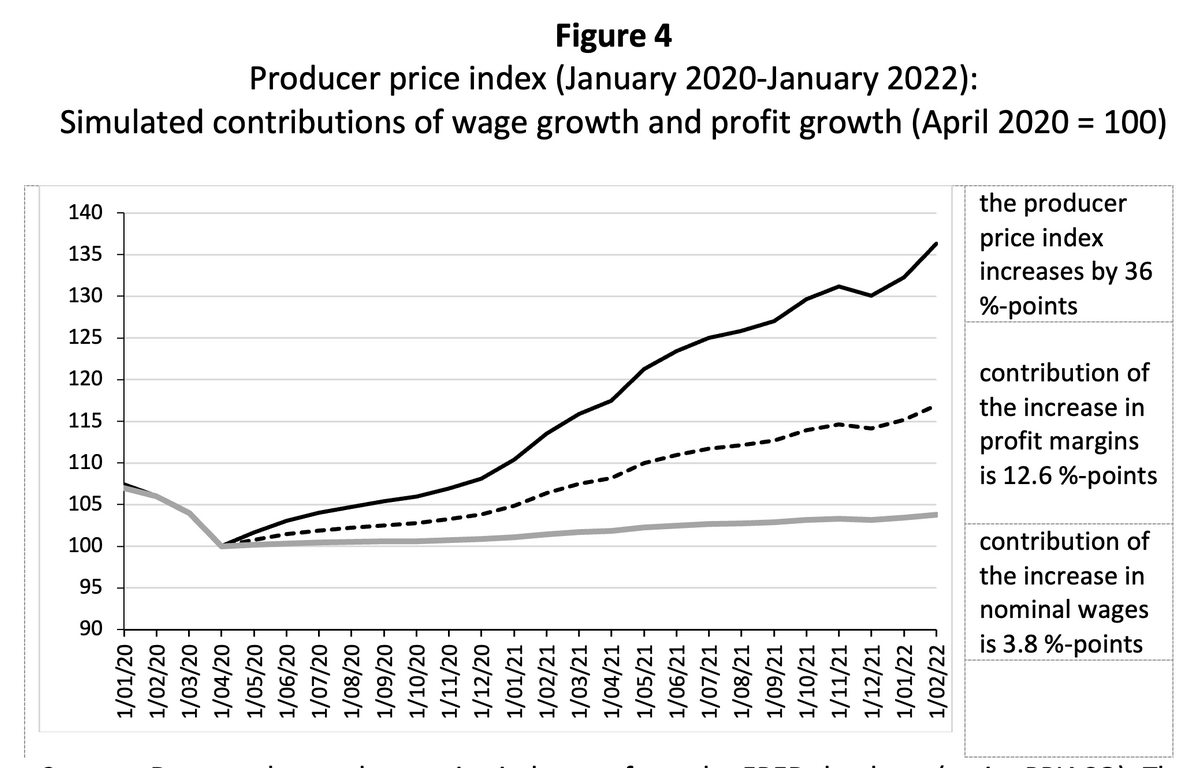

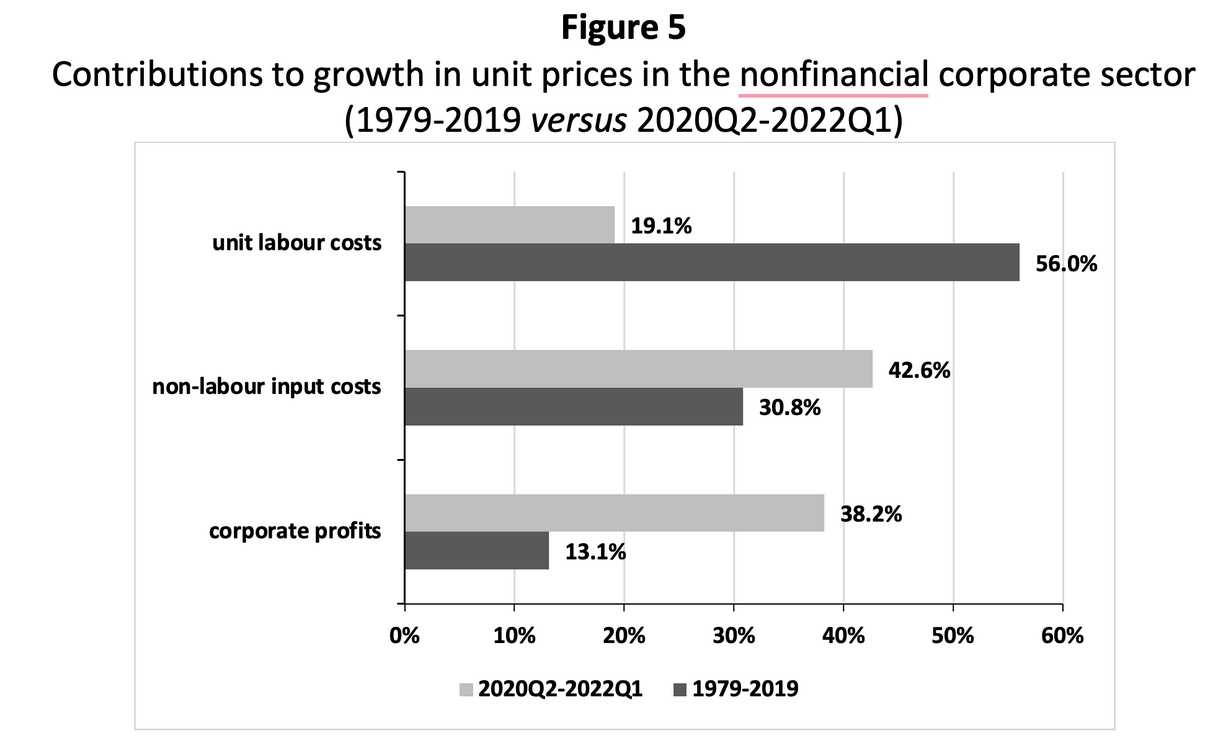

I estimated the inflationary impact of higher profits as well as higher nominal wages, using a simple model in which the producer price is determined by adding a profit mark-up to unit production cost which includes the unit cost of domestic and imported intermediate inputs and unit labor cost. Using BEA data, I find that higher nominal wages accounted for around 10% of the increase in the US producer price during 2020Q2-2021Q3, but the increase in net profits per unit of gross output accounted for more than one-third of the price increase (Figure 4).

These findings are similar to findings by Bivens (2022) who used a different approach. I have updated Bivens’ analysis to 2022Q1 and the results appear in Figure 5. More than 38% of the rise in the US inflation rate during 2020Q2 – 2022Q1 has been due to fatter profit margins, with higher unit labor costs contributing around 19% of this increase. Using Bivens’ approach, the contribution to inflation of higher profit margins is found to be two times as large as that of higher nominal wages. As Bivens (2022) notes, this is not normal: from 1979 to 2019, profits only contributed about 13% to price growth and labor costs 56.1%. The historically high-profit margins in the economic recovery from the COVID-19 crisis are difficult to square with explanations of recent inflation based purely on macroeconomic overheating. We have already seen (in Figure 3) that real wages are declining. And what Figures 4 and5suggest, is that recent US inflation has been caused more by a profit-price spiralthan by a wage-price spiral (as nominal wage growth is lagging behind profit growth).

Sources: Data on the producer price index are from the FRED database (series PPIACO). The contributions of wage growth and profit growth have been estimated by the author; see notes to Table 3.

Source: Based on Bivens (2022). Calculated using data from Table 1.15 from the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) of BEA.

The Perversity Trope: Excessive Nominal Wage Growth Reduces Real Wages

Domash and Summers (2022c) take their wage-price spiral argument one step further, claiming that it is not in the interest of US workers to demand higher nominal wages as compensation for the sharply rising costs of living. Their argument is that claiming higher nominal wages is a self-defeating strategy because individual gains in nominal income will be eroded by the consequent increase in aggregate inflation. This claim is a clear instance of what Albert Hirschman (1991) called the ‘rhetoric of reaction’, and more specifically, of the ‘perversity trope’: the claim that some purposive intervention to improve some feature of the political, social or economic order only serves to worsen the condition one wishes to ameliorate (Storm 2019).

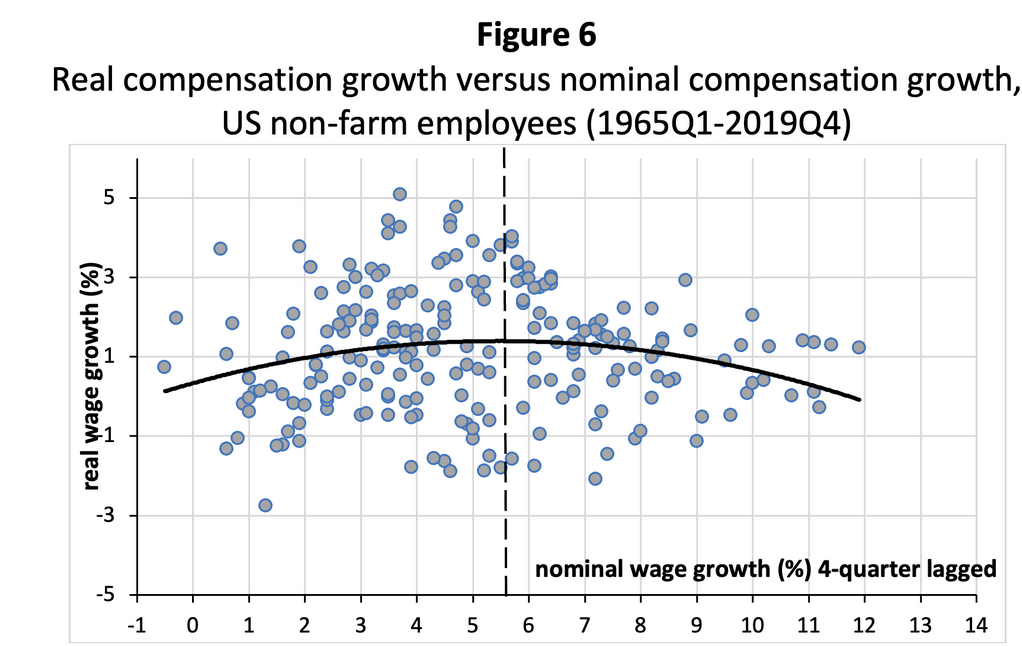

I have replicated the analysis of Domash and Summers (2022c) (see Figure 6) and obtain a similar parabolic—inverse U-shaped—relationship between lagged nominal wage growth and real wage growth in the US during 1965Q1-2019Q4. Domash and Summers use the annual growth rates of ‘average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees, total private’ as their measure of nominal wage growth; as shown in theAppendix, their measure gives much higher growth rates for nominal wages than alternative measures. Anyway, the fitted parabola has a turning point at a nominal wage growth rate of 5.6%; real wage growth peaks at 1.44%. If we take Figure 6 seriously (which we shouldn’t), this would mean that the average US real wage growth will decline from its peak level of 1.44%, the more US workers manage to push nominal wage growth above the threshold of 5.6%.

US workers be warned: nominal wage growth (calculated as the 4-quarter percent change in the hourly nominal compensation for non-farm employees from the BLS), running at 6.5% in the first quarter of 2022, has already passed the turning point of Figure 6, and hence, US real wage growth will only decline. To Domash and Summers (2022c) US workers act in a non-rational manner, hurting their own interests, by claiming excessively high nominal wage growth. It follows that rational workers would decide to restrain nominal wage growth (below 5.6%) and doing so, their private benefit (obtaining higherreal wage growth) will lead, as led by an invisible hand, to a social benefit as well (because it helps cool down the overheated US economy).

The particular ‘perversity trope’ used by Domash and Summers (2022c) can only work, however, if higher nominal wage growth raises the growth of nominal unit labor cost (ULC) and firms shift the higher ULC on to prices. Nominal unit labor cost growth is, by definition, equal to the difference between nominal wage growth and labor productivity growth. It follows that an increase in nominal wage growth that is accompanied by a similar increase in labor productivity growth does not raise nominal ULC growth and inflation. Hence, the correlation between nominal wage growth and real wage growth in Figure 6is somewhat misleading, because higher nominal wage growth will only impact inflation and real wage growth if it exceeds labor productivity growth and raises ULC growth.

In the Working Paper, I re-do the analysis of Domash and Summers using the 4-quarters lagged growth of nominal ULC instead of nominal wage growth. After all, nominal ULC growth is what matters for inflation. I obtain a (similar) parabolic relationship between ULC growth and real wage growth in the US during 1965Q1-2019Q4. The parabola has a turning point at a nominal ULC growth rate of 6.2%; real wage growth peaks at 2.5%.

What does my finding imply for nominal wage growth and the warning by Domash and Summers? Well, note first that labor productivity growth in the US during 1965Q1 and 2019Q4 was 1.9% on average per year. This implies that a nominal wage growth rate of 8.1% is consistent with a growth rate of nominal ULC of 6.2%. In other words, using nominal ULC growth instead of nominal wage growth, I find that the turning point after which nominal wage growth is associated with declining real wage growth is 8.1% rather than 5.6%. With US (quarterly) nominal wage growth running at 6.5%, it still makes good sense for US workers to push up nominal andreal wages—a very different conclusion from the one obtained by Domash and Summers, but nevertheless completely in line with their logic.

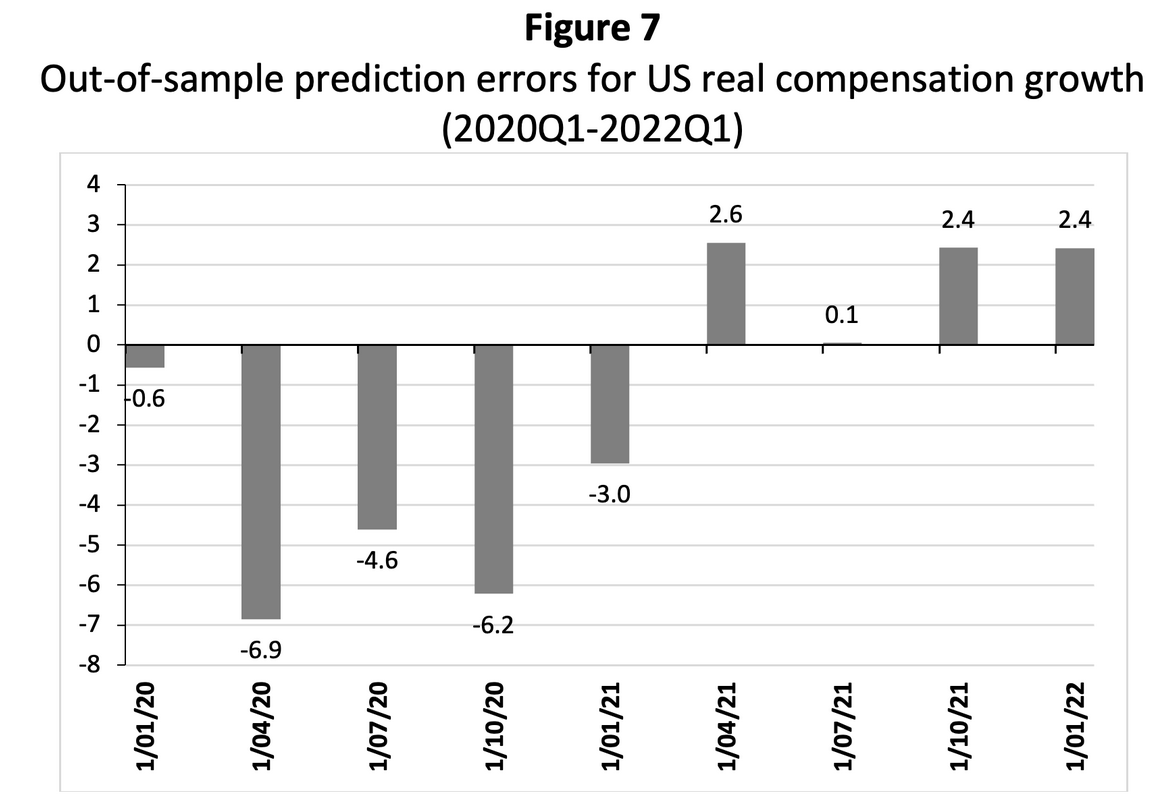

Their logic, or rather the lack of any substantial logic, is the real problem concerning the parabolic relationship between nominal and real wage growth, put forward by Domash and Summers. Let it be said, the two authors duly acknowledge that the parabolic relationship is not meaningful in a causal way, because “nominal wage growth and real wage growth reflect a variety of economic forces.” But they nevertheless quickly proceed with their argument, treating higher nominal wage growth as a cause of lower real wage growth. Empirically, however, the relationship is not strong, as the parabolic relationships explain only around one-third of the variance in real wage growth—which means that two-thirds are left unexplained. To see how this relationship performs out of the sample period (19651Q1-2019Q4), I used the estimated coefficients (reported in the notes to Figure 6) to calculate the ‘predicted’ real wage growth during the nine-quarters period 2020Q1 – 2022Q1, using actual (realized) 4-quarters lagged nominal wage growth. The out-of-sample prediction errors appear in Figure 7. Clearly, their ‘model’ does a very poor job of forecasting actual real wage growth during 2020Q1-2022Q2. Other factors—unprecedented lockdowns, labor market withdrawals and global supply-side shocks—did upset the US economy. The right conclusion is that past performance provides surprisingly little guidance to foretell the future.

However, ignoring the various empirical smokescreens, the greatest weakness of the argument put forward by Domash and Summers (2022c), is its a-historical nature. The wage-price-spiral claim presupposes that US workers have sufficient bargaining power to obtain higher and higher nominal wage increases. Structural evidence provided by Stansbury and Summers (one wonders whether this is really the same person as the co-author with Domash), shows that this presupposition is empirically incorrect. The reason is, of course, that US workers have suffered a long-term structural loss of bargaining power, due to declining unionization and globalization (outsourcing). As Stansbury and Summers (2020, p. 2) write, strong worker bargaining power “gives workers an ability to receive a share of the rents generated by companies operating in imperfectly competitive product markets, and can act as countervailing power to firm monopsony power.” Stansbury and Summers (2020a, p. 2) identify three main causes for the structural decline in worker power in the US:

“First, institutional changes: the policy environment has become less supportive of worker power by reducing the incidence of unionism and the credibility of the “threat effect” of unionism or other organized labor, and the real value of the minimum wage has fallen. Second, changes within firms: the increase in shareholder power and shareholder activism has led to pressures on companies to cut labor costs, resulting in wage reductions within firms and the “fissuring” of the workplace as companies increasingly outsource and subcontract labor. And third, changes in economic conditions: increased competition for labor from technology or from low-wage countries has increased the elasticity of demand for U.S. labor, or, in the parlance of bargaining theory, has improved employers’ outside option.” (Italics added)

Today, US workers almost completely lack the power to redistribute product market rents from capital owners to labor and, therefore, are in no position whatsoever to kickstart a wage-price inflation spiral. As a result, nominal wages are constantly chasing inflation, which is mostly due to higher import prices, higher energy prices, and higher profit markups—Alice’s Red Queenwas wrong: even if workers do all the running they can do, their nominal wages keep lagging behind the inflation rate and their real wages are going down.

In sum: A fair assessment of what has happened during 2020-22 is that US inflation has been driven less by (lagging nominal) wage increases and more strongly by increases in profit mark-ups. Fears of a building wage-price inflationary spiral appear to be misplaced.

Can the Fed Safely Bring Down Inflation?

Section 8of the Working Paper asks the question: can the Fed safelybring down inflation? The answer is a categorical no: the available empirical evidence is clear that small increases in the interest rate do not have much of an effect on inflation. First, the effects of higher interest rates come with a time lag and the gradual impacts (on PCE inflation) will not be felt during the three to four months. Second, an interest rate increase is a generic(blunt) intervention, which will affect inflation by depressing aggregate demand and economic activity but will achieve nothing in terms of lowering the price rises driven by supply-chain disruptions and/or geopolitical tensions, which are responsible for more than half of today’s PCE inflation. Third, empirically, the impact on inflation of an increase in the interest rate is quite limited.

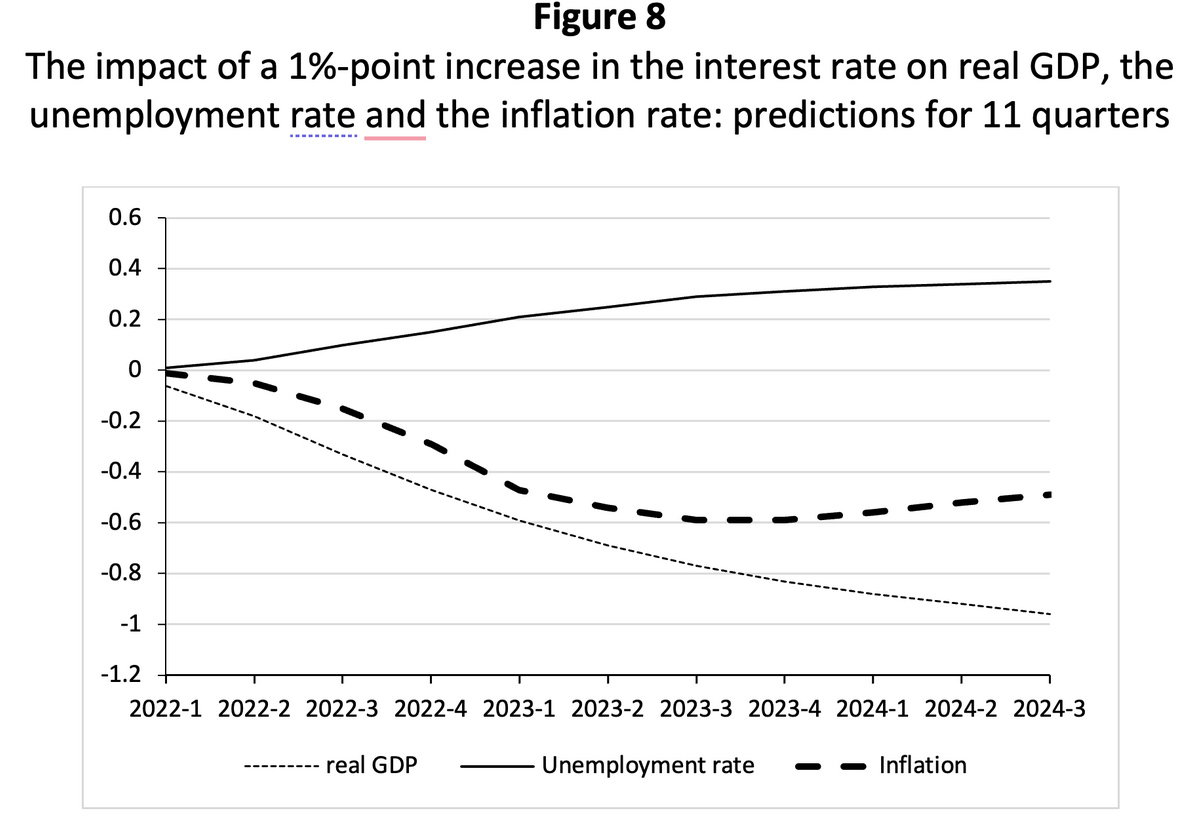

To get a structural sense of how effective monetary policy is in changing the inflation rate, real GDP, and the unemployment rate, we can do no better than consider Figure 8, which presents recent econometric-model forecasts for the US economy of a one-percentage-point increase in the interest rate for the forecast period 2021Q2 – 2023Q4 by Ray C. Fair. Professor Fair finds that after 11 quarters, a one-percentage-point increase in the interest rate results in a decrease in the inflation rate by 0.5 percentage points, a decline in real GDP of almost 1 percentage point, and an increase in the unemployment rate by 0.35 percentage points. Fair (2021, p. 24) concludes: “The effects on inflation are [….] about a half percentage point fall for a percentage point increase in [the interest rate], but it takes about 5 quarters to achieve this.”

Source: Fair (2021).

Suppose the Federal Reserve follows Summers’ advice and ramps up the interest rate from 1% to (say) 5% in the expectation that this will return the US economy to a stable-inflation equilibrium. Fair’s estimates tell us that this will not happen. Raising the interest rate to 5% will lower PCE inflation by only 2.25 percentage points—from 6.3% in April 2022 to around 4% in July 2022. The collateral damage of this failed attempt at inflation control will be non-negligible: after 11 quarters, real GDP will be lower by 4.5 percentage points and the unemployment rate will be higher by 1.5 percentage points.

There are reasons to believe that the collateral damage wrought by substantially higher interest rates will be even higher than predicted by Fair. The key reason is that more than a decade of extraordinarily low-interest rates has led to a significant increase in corporate and public debts and an unsustainable bout of asset price inflation in the housing market, the stock market, and almost all other financial markets. The Federal Reserve (2022) recognizes these non-negligible downward risks of monetary tightening to the American economy in its Financial Stability Reportof May 2022. Ergo: Large—Volcker-like—increases in the interest rate are off the table, because the resulting collateral damage is prohibitively high.

Since inflation cannot be brought down by monetary tightening alone, calls are growing to tighten fiscal policy as well. The idea is that public spending has to be scaled down in order to reduce the excess aggregate demand and excess labor demand, created by the fiscal relief spending that was (arguably) larger than the COVID-19 crisis required. The million-dollar question is whether the collateral damage of renewed austerity is a price worth paying for lowering inflation. If the inflation is driven by supply bottlenecks not directly amenable to fiscal and monetary policy, and sector-specific (in origin), then the fiscal tightening needed to lower inflation will be large and will cause substantial collateral damage, particularly for low-income households and small businesses. Austerity is not a rational solution to rising inflation in a time of corona and war.

The strongest call for fiscal consolidation is coming from proponents of the ‘fiscal theory of the price level’, who argue that the current surge in prices represents ‘fiscal inflation’. In this account, inflation is due to an erroneously overly expansive fiscal policy, which will not be compensated by (promises of) higher tax revenues and/or expenditure cuts in the future. In Section 9of the Working Paper, I offer a theoretical and empirical critique of the fiscal inflation hypothesis—arguing that it is a fallacious ‘theory’ and empirically empty.

In Section 10, alternative ways to bring inflation down are briefly discussed including the much-maligned strategic price controls, a tightening of position limits and an increase in margin requirements to eliminate commodity-market speculation, measures to remove some of the domestic supply-side bottlenecks in the US itself, and fiscal interventions to shield vulnerable households and firms from the negative impacts of high inflation.

Inflation in the Longer Run

Finally, in Section 11, I consider the longer-run context and focus specifically on the unavoidable inflationary impacts of global warming, ‘fossilflation’, and ‘greenflation’ (Schnabel 2022). I also discuss inflationary pressures originating from the long-run trends of rising transportation costs, rising commodity prices, fragmenting supply chains, and disorderly de-globalization. These trends are posing new—and daunting—challenges for monetary policymakers. The key issue facing macroeconomic policymakers is: how to deal with rising prices while also accelerating a green structural economic transition? When addressing this issue, central bankers appear to be stuck between a rock and a hard place.

This is because central bankers supposedly have to trade off safeguarding future financial stability (by keeping interest rates low today, supporting the climate transition but allowing for higher inflation in the short to medium run) versusbringing down inflation in the short to medium run (raising interest rates, but at the cost of slowing the transition to a net-zero economy and allowing for higher inflation in the longer run).

The trade-off is a false one, however. The reason is that slowing the climate transition is not an option: another decade of unmitigated global warming will lock the climate system into an unmanageable self-reinforcing process of climate change which risks putting us—humanity as a whole—on a one-way journey to Hothouse Earth (Schröder and Storm 2020). On that road, inflation rates will rise and become completely uncontrollable, while financial stability will be jeopardized.

In other words, in the face of the growing risk of catastrophic climate change, macroeconomic policy needs to be guided by only one principle: it is better to be safe than sorry. Hence, monetary policy should be made to support the transition to a net zero-carbon economy—and inflation control must be unconditionally subordinated to this overriding aim. Green fiscal policy and green industrial policies will have to do the heavy lifting—but these policies must be supported by (and not undermined by) a sufficiently accommodative interest rate policy. A supportive monetary policy will also include tightening risk and accountability regulations for banks and businesses so as to more rapidly phase out funding for fossil-fuel activities; dual interest rates (by offering a preferential discount rate for green lending); tighter regulation to eliminate commodity speculation; and some version of Green QE to help the decarbonization of the economy.

Monetary policy has to be reimagined to make it support the climate/energy transition—rather than obstruct it (as is the case now). Central bankers have to come down or be brought down, from their Olympus and act in alignment with the imperative of the net-zero transition. The clinical, social engineering approach to monetary policy-making that mostly favors financial markets (often at the cost of the rest of society) has to give way to more honest approaches based on the recognition that we are in all this together. One must recognize that a fair sharing of the inflationary and other burdens of the net-zero transition is critical to its viability (“distribution matters”) and acknowledge that the effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policies is overwhelmingly more important than whether their impacts are Pareto optimal or not. Financial markets need to serve the economy rather than live like parasites on it by means of speculation, socially useless regulatory arbitraging, and rent-seeking. There are no quick fixes and the longer macroeconomists continue to treat ‘the economy’ as a mechanical, ergodic, and closed system to which one can apply techniques of optimal control in order to identify some time-consistent monetary policy choice or optimal carbon tax trajectory, the more our economy and society will become locked into irreversible warming “heading for dangers unseen in the 10,000 years of human civilization” (Harvey 2022).

All this may well mean that inflation rates should be allowed to be higher (for some time) than the target of 2% and that alternative measures to control inflation and manage the societal and economic impacts of inflation (as discussed in Section 10of the Working Paper) have to adapt. A reimagining of monetary policy-making in the face of global warming is long overdue.

Appendix: A Note on Measuring Nominal Wage Growth

There are different measures of nominal wage growth in the US. Domash and Summers (2002a, 2002c) use the annual growth rates of ‘average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees, total private’. These two groups of workers account for approximately four-fifths of the total employment on private nonfarm payrolls. Other measures of nominal wage growth include the annual growth rates of ‘average hourly earnings of all employees, total private’ (which also include the wage increases of non-production workers and supervisory employees) and of ‘median hourly earnings of all employees’ (which concerns the growth of the wage ‘in the middle’ of the wage distribution, with 50% of wage earners earning less and 50% of wage earners earning more).

As is shown in Table A, the growth numbers differ depending on the measure of wages used. According to the wage growth measure for production and non-supervisory workers (W1) used by Domash and Summers, nominal wage growth in the US during 2021-Q1/2022-Q1 was 6.7%. But the growth rate of average nominal wages of all US workers (W2) was only 5.4% in 2021-Q1/2022-Q1. Median wage growth of all employees (measure W3), finally, was 4.3% over the previous year. Wage inflation exists, to some extent, in the eye of the beholder.

Table A

Nominal wage growth in the US: different measures

| W1 | W2 | W3 | |

| Average hourly earnings of production and non-supervisory employees, total private

(% change from a year ago) |

Average hourly earnings of all employees, total private

(% change from a year ago) |

Median hourly earnings of all employees

(% change from a year ago) |

|

| 2021-Q1 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 3.5 |

| 2021-Q2 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.4 |

| 2021-Q3 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 3.5 |

| 2021-Q4 | 6.4 | 5.2 | 3.7 |

| 2022-Q1 | 6.7 | 5.4 | 4.3 |

Source: FRED database.

_________

[1]According to Alan Blinder, a former vice-chair of the Federal Reserve, the Fed managed to achieve a soft landing in exactly two out of 11 tightening cycles since World War II: the first one occurred in 1966 and the more recent soft landing happened in 1994. That makes one success story in the past 50 years (Mason 2022).

See original post for references

If you had told the average American in 1977 that they were in the very last days of a postwar economic golden age, would they have believed you?

Should we in 2022 be trying to savor these last days of whatever we have?

I graduated high school that year. I was firmly of the belief then that if this was as good as it got, we should just bag it right now. Who knew?

Your point about oil investment…

“shareholders prefer that companies return cash rather than invest” .

This can be extended to the overall inflation problem. The fed has been artificially supressing rates for over a decade.

Why? They are pushovers..

Investors/companies want cheap money and bailouts. This prohibits real market forces from driving investment.

People generally fight the last war, not the current one.

For a decade shareholders preferred that oil companies drill, drill, drilled. Oil prices fell: the net effect to bury burned dollars into shale and to bankrupt a good number of oil companies.

The lesson learned from this last war was to stop drilling. Now “shareholders prefer that companies return cash rather than invest.”

The right thing to have done would have been to return cash to shareholders from 2014 to 2020 rather than to drill, but to have started drilling in 2020.

Doing this would have required the courage to be countercyclical, to not follow the crowd. This is really hard to do. Really hard. I do it more in hindsight than in foresight. It’s not simply that

It’s more simply not being smart enough and not being brave enough.

Investment in new real assets increases supply and moderates inflationary tendencies. Returning profits via share buybacks can be seen as a type of concerted real goods “supply suppression” which then gives companies in concentrated goods and services sectors more market power. This does seem to be what this paper cites, with the lions share of returns going to profits rather than wages.

One remedy for this is to grant a lower capital gains rate only to gains from investments in new productive capacity, rather than to windfall (paper) gains from stock buybacks and Fed QE.

Arguably, a lot of the supply bottleneck problem can be traced to our tax code promoting unicorn investment but not real investment.

What an amazing coincidence that the three episodes of serious inflation witnessed in the last 50 years in the U.S. have all taken place at the same time that oil prices dramatically increased. Thankfully, we have geniuses like Summers to instruct us that the problem is really working people and their damned bargaining power.

I predicted a year ago that there was no way Powell would raise interest rates substantially… because he had to know that it would crash the housing economy (not just buying and selling but construction and personal finance, which is now importantly based on spending financed by home equity), which would crash the rest of the economy. I’m feeling less and less confident in that prediction.

I have been impressed by everything of Storm’s that I have read. This one seems quite meaty and will take some time to digest.

Very good point. Why do economists blame the “wage price spiral” and not the “oil price spiral”? The latter tends to get to root cause-and-effect, e.g. on everything that depends on energy including fertilizer, food, travel, space heating–and ultimately wages too.

The role of energy prices also helps explain periods of low inflation. It’s no coincidence that the huge ramp-up of U.S. domestic oil and gas production, which made the U.S. self-sufficient in energy for the first time since the ’50’s, put downward pressure on global energy prices for the decade after 2012. This was was also a period of sustained LOW inflation.

So then let’s examine why we don’t focus more on energy price drivers? Maybe the best inflation control strategy would be to stop disrupting some Petro States with military actions (Libya, Iraq) and imposing sanctions on others (Russia, Iran). Most economists are, unfortunately, not foreign policy or energy experts. Also, there are political drivers against looking too closely at such root causes, as tracing the blowbacks from U.S. foreign policy mistakes can be hazardous to the leadership class.

It does appear, from the above article, that U.S. and international rig counts are climbing back up, so eventually oil and gas prices should start coming down again (due to higher production), and therefore, eventually, inflation. Ironically, even though I’m concerned about climate change, I do believe that aggressive expansion of shale oil and gas supplies are needed as a bridge to a peaceful world, without which mulilateral cooperation on de-carbonization cannot happen.

The economics of energy should be a required part of every academic economics curriculum.

Because capitalist will use any stick to beat the labor dog.

Being the boss is the only thing more important than being rich.

Economists mostly work for the boss, they say what the boss wants said in whatever way seems appropriate at whatever moment they write.

“Court economists” is the term, I believe.

Great article! But it does seem to be a repeat of what I’ve learned here over the years. So many smart people are aware of what is happening with our economy but unfortunately, they are not the ones that are getting through to the general public. I was talking to a neighbor yesterday, and yep, she repeated that same old trope about wages causing inflation. She didn’t even know that corporate profits had risen – she thought that they were falling because, you know, stock markets.

The best line in the whole article:

“Financial markets need to serve the economy rather than live like parasites on it by means of speculation, socially useless regulatory arbitraging, and rent-seeking.”

Anyone who has ever been around ranches knows there is only one way to deal with parasites – and that is to kill them before they kill the animal. Sadly, I don’t think Ivermectin will work here.

Another line i liked was when the author argues that according to Summers et al. “workers are not rational” which 1) breaks the assumptions of most econometric models and 2) is of course very PMC, very elitist. We the peasants deserve whatever these geniuses want to inflict on us.

Very good article!

Unlike investors, who rationally plowed their own money into Wework, Theranos, Uber, and thousands of crypto schemes.

When I heard about rational expectations was when I decided I could not take economics and its physics envy seriously. A silly, lazy assumption – not just applied to the above-mentioned “peasants”.

No thought required. Just buy an index fund or the latest variation on the theme—

Some claim that larry summers is not egalitarian, I disagree, he wants all workers to be compensated equally with bangladeshi garment workers, and that monopolies are superior because competition is wasted profits…wall st. uber alles… /s

I agree with Left in Wisconsin, a great and meaty post, thanks

The pervasive entitlement and corruption of the American neoliberal caste system in a nutshell. Cambridge vs. the Massholes.

I’m currently having a house built in a climate refuge — I’m actually on the building site as I type. My contractor has been building houses for 40 years and he tells me that he’s never in his life experienced the current level of price-gouging by his now corporate-owned and globalized monopoly suppliers.

High fuel prices are the BIG CLAW BACK from 2020-21. Simply reclaiming old profits.

I did not see much in this piece on decreasing the money supply with tax policy. It seems to me that a significant tax increase on everyone would cut spending as well as raising the interest rate. But what do I know. Maybe someone can answer.

The Fed lost control of the money supply decades ago.

Inflation — not the money supply — is the problem. All that is required to lower the rate of inflation is to redefine how the rate of inflation is calculated. If the FED is not up to the task they should outsource the problem to the guys who calculate the rate of unemployment or the guys who calculate the cost of living increases for Social Security — perhaps the guys who calculate GDP know some tricks [although they are best at figuring in increases in a measure rather than decreases as are needed].

So Greed is a real thing, and impacts inflation a whole lot, but we have to make room for the rule that corporations are supposed to be “more greedy,” to maximize profits, obliterating the liabilities of off-loaded externalities in the double entry bookkeeping. So it’s just the LOCUS of the greed that appears to be the problem — it’s “shareholders,” not CEOs and lobbyists and PE and VC and corruption.

It used to be that corporations were expected to serve some kind of public purpose, to earn the extraordinary advantages of eternal life and amassing of power. ESG obviously is not filling that function. And when was the last time that a corporation was shown to be guilty of mass murder and outrageous looting and destruction, and was sentenced to death?

And as Al Capone said, “Capitalism is the racket of the ruling class.”

JT cuts to the bone!

Every tool in the Fed’s “toolbox” ultimately creates the Cantillion effect. It’s by design since 1913.

Thx; I don’t recall hearing of the “Cantillon Effect”, despite my BA Econ. To be fair, the (US) Fed didn’t create or cause the Cantillon effect, but it does seem like Aldrich & Co designed the Federal Reserve System with Cantillon effect in mind – to make sure that Wall Street always gets the first (and therefore biggest) piece of the pie. That is certainly what’s been happening for some time, but it’s gotten even worse with the Fed’s reactions to the GFC & then Covid.

This was my intro to the Cantillon effect. It’s a year old, but super interesting.

https://mattstoller.substack.com/p/the-cantillon-effect-why-wall-street?s=r

Quite a number of years ago I pissed on Nelson Aldrich’s grave.

I wonder if all this talk about stagflation is a fear that sales volumes might be collapsing.

If sales volumes have not recovered to their pre-pandemic levels, then companies might be raising prices to try and maintain their past revenue and growth levels. It’s hard to tell if this is the case, because most companies are not required to report how many units of a good or service they sell.

We can probably assume that clothing retailers are selling a lot fewer units post-pandemic, because of work from home and less frequent social engagements ( restaurants, theater, ect. ). And we can similarly assume the travel and hospitality industry is selling a lot fewer of every service they offer post-pandemic. And we can similarly assume that grocery stores were selling a lot more units at the height of the pandemic, but this has likely tapered off as lockdowns have relaxed. Anecdotally, I see far fewer people on weekends in grocery stores which suggests consumers might be buying less because of much higher prices. This at a time when some of the biggest beneficiaries of pandemic lockdowns, like Amazon and Target and Walmart, are now reporting major inventory gluts from overstocking during the pandemic good times ( Amazon is currently trying to sublet 30 million square feet of overbuilt warehouse space ).

One industry where we can see unit sales is the automotive industry. According to WolfStreet, the number of new vehicles sold in 2021 has collapsed to 1978 levels, but the sale price of these vehicles has spiked to record highs. And the number of new vehicles sold in 2022 are so far ( up to May ) about 32% lower than 2021 levels.

I’m not suggesting that raising prices has not been profitable ( so far ). There are lots of stories that describe how inflation has led to soaring corporate profits. And corporations that regularly sell only a fraction of their finished products, like the highest end luxury houses, will probably benefit most from being able to grossly inflate their prices.

But all of this is short term thinking. If you keep raising prices without maintaining unit volumes, then volumes will keep spiraling down in a race to the bottom. And this will cause horrible problems for consumer health and consumer demand.

Good point. Lower volumes mean lower economies of scale, which must be offset via higher prices.

It’s possible we are now entering an era of retrenchment from globalization, if only to bolster national supply chain resiliency. The downside could be more redundancy and fewer economies of scale (and other efficiencies), and thus more upward pressure on prices.

More generally, to the extent that higher interest rates discourage necessary real investment to expand supply, aggressively raising them will only make things worse.

It seems we need to differentiate, in our policies, between “good” inflation and “bad” inflation. The interest rate sledge hammer crushes both. It seems to me that the Fed and fiscal policy makers need to consider, not just inflation and employment, but incentives to invest in the real economy in the right ways to achieve long term goals, e.g. expanding infrastructure, improving resilience, and others, to reduce inflation risks over the long term.

Why are these “ economies of scale“ supposed to be efficiencies? When what they clearly do is create brittle chains that already are breaking down. When they’re not look at Russia for a model of how a nation might proceed in terms of creating flexible and sustainable and durable supply chains and economic activity.

Anyone taking a look at the ruble to dollar conversion these days? And who has surpluses?

“Efficiency” and “efficiencies,” as those terms are so glibly used, with so little recognition of how they manifest in practice, seem to me to be emblematic of the idiocies of neo classical so-called economics.

The comparison between tobacco companies and oil companies is particularly telling. In the face of relentless government opposition to their business model it is entirely rational to limit new (and due to regulatory hostility highly risky) investment and maximize the return on what has already been invested. The extensive regulations and hostility of the regulators mean that anyone who wants to compete with you will have an insurmountable barrier to get into the market (no doubt the regulators see themselves as heroes for preventing an expansion of the market in this circumstance).

The extrajudicial cancellation of Keystone XL caused the loss of billions of dollars of investment on a project that was entirely legal, This creates immense unpredictable risk of pursuing other ostensibly legal projects. In addition the enormous increase in red tape that the Biden administration added to almost any new drilling project immediately upon taking office, mean that this crisis is going to continue for several years. It also means that there is now a huge barrier to entry that keeps the wildcat drillers from jumping back in and taking advantage of the situation the way they did during the Obama administration.

Oil is the input to almost everything in the economy, whether as energy or as a base chemical. If your input cost for everything rises you will see prices rise everywhere.

Libertarian says “regulation”BAAAD!” Offloaded externalities GOOOD!

Quelle surprise!

Cuz pipelines create jawbs, and never leak, and never involve stealing private proppity, using gummint clout, for private gain…

“There are reasons to believe that the collateral damage wrought by substantially higher interest rates will be even higher today than in 1980. The key point is that more than a decade of extraordinarily low interest rates have led to a significant increase in corporate and public debts and an unsustainable bout of asset price inflation in the housing market, the stock market, and almost all other financial markets.”

The money made from the post-2009 fantasy finance asset prices will now be used to buy up the struggling companies that can’t handle the interest rate increases. More concentration in the hands of the few is the result.

Rinse and repeat.

Indeed — who would benefit from increasing interest rates? If the smart money has cashed out their gains in stock shares, the available properties for profitable rent increases have been bought up, and small business and private rentiers have been pushed to the edge, who might benefit from increasing interest rates and a little austerity for the Populace?

I like the insight. I have been in the camp of more post WW2/depression inflation management vs 70’s/80’s inflation management… i.e. fixed rates, let inflation run so everyone can pay down their debt including the government. However what you are saying seems to make more sense on squeezing the market at least temporarily to let the big dogs sweep everything up. It was caused by a different set of problems but that is exactly how the oil market was played when prices collapsed in 2013 then the big dogs came in and bought everything out.

All decisions involving the economy will be made by following the “logic” of Summers. In other view will not matter. It’s the greed of workers who are at fault-as always. As far as dealing with global warming that is not something that will ever happen.

However, what happened to the narrative of President Biden that it is all Putin’s fault. His solution is to have regime change.

Agree with the points about the effects of Covid on employment.

But doesn’t it also bear consideration that worker participation has been on an accelerated downward spiral since around 2000 and EVEN continued after recessions?

Excellent post, my thanks again to Yves. So much truth in Storm’s dense — and accurate summary statement (emphasis mine):

We are out of time.

That quote caught my eye as well. Not only are we not all in this together, the small number of people and organizations making this happen appear to be the most selfish people to ever darken the doors of power and influence.

There’s too much voter ignorance and misdirected rage for this truth to be seen and understood.

The world’s energy and food resources now being managed by Wall St trained and lead economists and managers. All who have never actually had to lose a job or get fired because the Fed was there to print trillions everytime they should have been flushed completely out of civil society. What could possibly go wrong?

It will be more Neutron Jack Welch to the rescue!

As interviewed on CNBC –

I have fired the inhabitants of twenty African countries since they were demanding excessive food, and that would impact ongoing profit taking opportunities in our Ukraine regional operations. They will be free to then interview for the new job opportunities in teleheathcare since it turns out there are more trained healthcare workers in these countries than are left in America.

Yes, we are proud to announce our Focused Utilization Care* as your best Medicare choice, we have the full financial support of our partners in the US government and expect to bilk, um, earn trillions.

*F U Care is a registered trademark. We are pleased to also annouce F U NHS for our British partners!

Never understood why the term isn’t FY?

This is a great article – although since it confirms my opinions, I admit to bias.

We always need to remember that the economy should serve society rather than enslave it. It needs to provide the stuff that people need or want – which is the part that most commentary reflects – and let them get that stuff in ways that are fair enough – which is more often missed.

Fighting inflation by raising rates makes it harder to provide stuff and even harder to distribute it fairly. The “collateral damage” when people lose jobs, lose property, or fall into debt is that they can’t even get the stuff they need.

Rising prices reduce demand and increase production. In that sense “inflation” is self-correcting as long as there is unused productive capacity. As the article points out in the employment-populations ratio chart there is still suppliable labor. Of course, not every part of the economy has slack. For example, as has been discussed elsewhere in NC, refining capacity in America is pretty well maxed out, and cannot easily be expanded.

But in most cases, there is unused capacity, or capacity could be expanded.

Here concentrated control is the biggest impediment. Why change things if you are in control? Riding the wave of increased profit is the safest course. It’s also the “greediest” course but really, the fact that it’s the “safest” course is the deciding factor for as long as you can get away with it.

So the recipe for fighting inflation is to wait, to empower people, and to disempower those with the most power. Of these three the only thing in the power of the central banks is to wait, to do nothing in the face of political pressure, but rather to push back and point out what political actions might be needed.

Fat chance….

No mention of Quantitative Easing? (Is that now considered merely a way to “lower interest rates” below the ‘lower bound’?)

That such creatures can say ” its cause employees are greedy” with a straight face is the very root of the larger problem in encapsulated form

And this is germane and excellent:https://www.strategic-culture.org/news/2022/06/06/the-world-doesnt-work-that-way-anymore/

Again…dying hegemon, lashing out, still dreami g that it will remain on top forever

Aside from the Arab oil embargo and its broad impacts on the prices of all goods and services that rely on petroleum, the stagflation of the 1970s featured a cost-push ratchet effect as higher prices drove organized labor to demand higher wages, which thereby further increased costs. I believe much was made of this as a tool to further sully organized labor’s already damaged reputation. Even in the 1970s not all labor was organized labor. Organized labor may have had some positive impact on raising all wages, but it was easy for Corporate powers to suggest organized labor took the greatest part of the wage gains for itself and raised inflation for all … while minimizing notice of other causes.

As this post makes clear, today’s stagflation is a different beast. The decline of organized labor as an effective counterweight to Corporate power reduces the old cost-push inflation model to an absurdity. This post describes a cost-push ratchet that positions supply shortages opposite Corporate monopoly and monopsony power — supply shortage costs and profits increases push inflation. In the 1970s wages and also prices would go up, but seldom go down [nominally]. In the 2020s prices go up, and profits go up and seldom go down [nominally]. The deconstruction and geographic distribution of the production and supply chains couple with true supply reductions as easily extracted resources are depleted, and Corporate monopoly and monopsony power are free to operate in generating and augmenting further shortages. In this regard I believe the post implies but leaves incompletely unexplored a further aspect of today’s inflation. Price increases due to shortages become locked in even after the shortages have been relieved through Corporate monopoly and monopsony power. This is a particular variety of the profits ratchet the post describes. A further aspect of this effect resides in the power of Corporations to direct policy including, I believe, policies like the u.s. government’s many economic sanctions against various nations.

Monetary policy as a tool for dealing with today’s stagflation seems, to me, quite as ill-founded and destructive — likely far more destructive — than it was as a policy for dealing with the stagflation of the 1970s. Let Paul Volcker lie in peace and keep very far away from us and from further exploits in destructive monetary policy.

[I must disagree with all the arguments that Labor is acting irrationally, contrary to its interests through pushing for higher wages now or in the ‘organized’ 1970s. The fallacy lies in thinking of labor as a single integrated entity — a not uncommon problem in Macro analyses. My wage gains may come at the cost of others and may lower real wages … but in the end each plays for their own interests. I want the biggest piece of the pie though my action and the actions of many may result in a shrinking of pie for all.]

Why Biden and the Democrats are toast (not that their opponents are better, but that is not the subject) Part MDCCCLVII: Since yesterday at noon I made a 325-mile round trip. Filled up the car on the way back earlier this afternoon: $54 and change, for a MINI Cooper convertible (35+ mpg on the highway, 2011 vintage), and the gas tank was still one-third full. My round trip to work is 1.8 miles, when I drive, and my better half can see her place of employment from our front porch, so we really don’t care about gas prices. Much. We are part of a very small minority in this country. And Biden is still gobsmacked at his poll numbers…

Monetary policy is a weak tool. Investment in productive assets isn’t very sensitive to interest rates, companies that have a formal process use quite high internal hurdle rates (eg, 16% pa or 18% pa, or a 4-5 year payback) for many (generally good) reasons, and those rates aren’t adjusted very often. It takes a really big change for monetary policy to have an impact.

The bite instead is through consumer lending (particularly automotive) and mortgage rates that affect new home construction. But housing starts aren’t unusually high (or unusually low), and the auto industry (both new and used car prices) affected by supply-side issues stemming directly from the pandemic. Latent demand is around 17 million units; chip-constrained (NOT labor constrained) capacity is about 15 million units. Rental car companies “de-fleeting” 9-12 month old cars would normally supply 2 million or more units a year into the used market. Fleets normally purchase base trim vehicles at a discount, but car companies aren’t making those. So there goes the largest source of “lightly” used cars, paralleled by owners keeping their off-lease vehicles rather then returning them to dealerships. High interest rates won’t increase the supply of semiconductors, and the rental car companies can’t de-fleet vehicles they don’t have. Low spring-summer 2020 car sales mean few spring-summer 2022 off-lease trade-ins. High interest rates won’t change that. And we’re still not driving at pre-pandemic levels; gasoline demand isn’t the problem, it’s global (not US domestic) supply, summarized in one proper noun: Putin.

Unfortunately, monetary policy isn’t just a weak tool, it’s the only policy tool. Supply-side oriented policies don’t work in an electoral cycle timeframe. I spent time today with two of the biggest automotive chip manufacturers, they’re already over capacity, any blip – a fire at a Renesas fab in Japan, the cold snap that shut down fabs in Texas – introduces new bottlenecks. Adding capacity is a 2-3 year process, if that is all goes well at the suppliers who make the equipment a modern “fab” needs, you need every machine in place before you can start ramping production.

The Fed feels it has to be seen to be doing something. But seriously, Fed Funds are still under 1% pa (to be specific, 0.83%). Rates would already be much higher if the Fed really thought inflation was a demand-side problem. To date it’s much ado about nothing, noticeable only because of a long period of no movement, covered by financial journalists who weren’t yet born in Volcker’s day.

Russia, supply chain disruptions, and Covid stimulus payments.

On Shale Oil fixing things:

Chanos has been extremely critical of the shale oil business:

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/us-shale-oil-gas-investors-171420840.html

Drilling shale wells is extremely capital intensive and wells deplete much faster than traditional wells (meaning a lot of the accounting overstates earnings by understating depletion). Shale companies from 2008 through 2017 focused on deploying capital to expand production, which lowered oil prices internationally but left them with insufficient revenues to meet their CAPEX, and service their debts, let alone pay dividends. The oil war of 2020 left many of the shale companies bankrupt, and those that made it went through a near death experience. US Shale is not the lowest cost producer, so they shot themselves in the foot. Yes, they should pay back dividends rather than waste the money expanding production in a way that destroys their creditworthiness.

Shale is not going to save the US from growth killing >$80 per barrel WTI crude. The companies are not going to repeat their mistake due to the insistence of their bankers and investors, which have become smaller due to ESG, etc., anyways. While it is possible in 3-5 years fading memories of near death will lead to another cycle of mismanagement by expanding production and lowering prices below what they need for sufficient return of capital, it won’t happen in time for Biden. In addition, cost and availability of supplies like sand make it extremely difficult to expand production even if they wanted to.