By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

“Change and decay in all around I see.” –Henry Francis Lyte, Abide with Me

Utah’s Great Salt Lake is drying up. A resident mourns what was:

That used to be full of water. My wife asked if a piece of metal was a wheel chair ramp…nope, the old dock.

Next a view from the visitor's center. The causeway in the distance had water up to the edge when I was in HS. pic.twitter.com/IkYisSUZg2

— Michael Kofoed (@mikekofoed) July 29, 2022

Reading @mikekofoed thread, I naturally wondered what the status of “land artist” Robert Smithson’s iconic “Spiral Jetty,”[1] which (when created) jutted into the Great Salt Lake. How it started, very beautiful:

(Smithson is said to have selected the site for the red color, seen here.) How it’s going, also very beautiful:

Still beautiful, but a jetty without water. The Salt Lake Tribune raises a classic question in aesthetics: “Spiral Jetty: A barometer for the Great Salt Lake, or a work of art unto itself?”

Like any work of art, the value of Spiral Jetty — easily the most recognizable artwork in Utah — depends on how you look at it.

Jaimi Butler, the coordinator of Westminster College’s Great Salt Lake Institute, called the 1,500-foot rock formation artist Robert Smithson created in 1970 an “artistic water gauge” of the Great Salt Lake….

The jetty “is a barometer for the ways in which we are operating in a climate emergency,” said Lisa Le Feuvre, the head of the Holt/Smithson Foundation, which oversees the creative legacies of Smithson and his wife, Nancy Holt.

Smithson never intended Spiral Jetty to be a barometer of anything, said Hikmet Sidney Loe, a former professor at Westminster College who wrote “The Spiral Jetty Encyclo” (University of Utah Press, 2017), a comprehensive book about Smithson and his most famous work.

“He wanted a very dynamic environment, so the salt crystals would form, dissipate, the colors would change and the water would rise and fall,” Loe said. “But he wasn’t [thinking], ‘In 50 years, here’s what people are going to think about my work.’”

The classicist’s dulce (sweet) vs. utile (useful) dichotomy (but why not both? “It’s a dessert topping! It’s a floor wax!”). However, confronting Smithson’s vast body of work, I find I don’t have a coherent aesthetic I can use to give an account of them, so I won’t go further with theory. (I have a few claims I make about art, but that’s not the same as having a theory). I will also shirk my responsibilities by not giving even a potted biography of Smithson, a summary of his writings (autodidactic; very 60s; prolix; less interesting than the art. Here’s an example). Nor will I expound upon the concept of entropy — “things fall apart” will do — or explicitly relate the concept to Smithson’s art. But you’ll know it when you see it:

If anyone is working on Robert Smithson and needs an image to illustrate the entropic principle I can probably help pic.twitter.com/EBGqzFz9tM

— Jeremy Millar (@jeremy_millar_1) May 18, 2022

Sadly, then, this post will not be a critique or even an appreciation. Rather, I will present a series of Smithson’s works — or, rather, images of Smithson’s works — first some minor ones, and then three major ones: “Spiral Jetty” itself, then “Partially Buried Workshed,” and finally “Amarillo Ramp.” My and your remarks will then accrete round the armature of the works. In more or less chronological order, “Heap” being early, and “Ramp” being late, indeed final:

“Heap of Language”:

robert smithson, a heap of language pic.twitter.com/QyPO8Jjjw2

— wordvoid (@wordvoid) July 28, 2022

Like a heap of sand, one more grain will trigger an avalanche. Bloggers know this feeling.

“Glue Pour”:

ROBERT SMITHSON

Glue Pour, 1969large drum of glue, industrially produced by National Starch and Chemical Company poured over a hill pic.twitter.com/6IkPJFtOWS

— Yempejji Culture Channels (@yempejji) February 3, 2022

Here is the view of a Canadian art critic:

When the drum delivered by National Starch and Chemical Company was pried open, its sticky contents were a garish orange—not the expected neutral grey. Buoyed by the convivial mood of his co-conspirators, master of ceremonies Robert Smithson proceeded to lower the barrel into position atop the steeply inclined clay bank near the University of British Columbia campus, a site scouted by Vancouver artist and accomplice Christos Dikeakos.

Dikeakos’s grainy documentation of Smithson’s Glue Pour (1970) captures the prehistoric drama of the event. The adhesive slime, released from its plastic liner, conjured the manufactured terrors, and unintended comedy, of a science-fiction movie. “At the commencement of the pour everyone laughed or had a smile on their face,” recalls Dikeakos. Yet it was only in retrospect that Smithson’s simulated magma flow evoked, for some, a sexually charged travesty of Modernist painting’s theatrics (picture a cross between the poured canvases of Helen Frankenthaler or Morris Louis and a stag film).

Or perhaps The Blob? (Although it’s hard to imagine conviviality among those Present at the Creation it’s not, I suppose, impossible.)

“Line of Wreckage, Bayonne, New Jersey”:

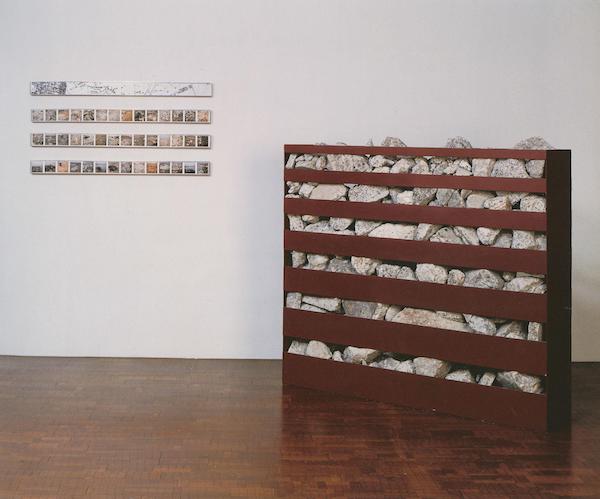

I love the museum label: “Painted aluminum container with broken concrete, framed map, and photo panels.”

The Holt Smithson Foundation[2] describes the work:

Broken pieces of concrete gathered from a destroyed New Jersey highway are arranged inside a steel box with horizontal openings, alongside a map and a series of photographs on the wall providing geographic and visual context. Smithson illuminates the forgotten, displaying post-industrial rubble as if it were an ancient ruin. The result is both anticlimactic and tragic. Visually mundane, the site is afforded our attention within the gallery setting—and its material remains demand a reckoning with the pervasion of loss in an otherwise invisible place.

And the theory behind the work:

The Nonsite (an indoor earthwork) is a three dimensional logical picture that is abstract, yet it represents an actual site in N.J. (The Pine Barrens Plains). It is by this three dimensional metaphor that one site can represent another site which does not resemble it—thus The Nonsite. To understand this language of sites is to appreciate the metaphor between the syntactical construct and the complex of ideas, letting the former function as a three dimensional picture which doesn’t look like a picture.

As a photographer, I have to give this some thought. After all, one photographs at a site. And if the photo is hung, it can only be at a nonsite.[3]

Now let’s turn to some of Smithson’s major works. First, “Spiral Jetty” itself. Although we discussed the dematerialization of the substance in which the jetty was immersed, we never discussed the materiality of the jetty itself, 6,650 tons of sand, earth, and rock (primarily black basalt), delivered and positioned by two dump trucks, a tractor, and a front-end loaded. Here is a long thread on that topic:

Let's begin with the sand. It's difficult to see from the photo but this sand is special. The grains at the Great Salt Lake are ooilitic, meaning they are well rounded grains. This leads to a slippery walk where they are dry and you sink into the sand further than "normal" sand pic.twitter.com/m0P7iTFC0J

— Carly Lee (@_Sackung) December 6, 2020

“Partially Buried Woodshed,” at Kent State University in Ohio:

Here is a thread showing the construction:

Robert Smithson, Partially Buried Wood Shed, 1970 pic.twitter.com/C37AXeXNVu

— Yempejji Culture Channels (@yempejji) June 11, 2022

(Earth was loaded onto the roof of the woodshed until the center beam cracked.) And here we see the post-Kent State University Massacre graffiti:

Robert Smithson, 'Partially Buried Woodshed' (1970) pic.twitter.com/0EOGNbKEo3

— Jeremy Millar (@jeremy_millar_1) May 4, 2021

Hilariously, however, the real forces of entropy at work were not the massacre, nor the slow rotting and ultimate collapse of the shed, but — just let me position my knee here so it doesn’t impact anything — the university administrators:

[Smithson] valued the work at $10,000 and donated it to the university, asking that no changes be made and that the structure be allowed to deteriorate naturally. Shortly after the May 4, 1970, Kent State shootings, an anonymous person added the inscription ‘MAY 4 KENT 70’ with white paint to one of the structure’s horizontal beams.[4] The addition of the message about May 4, 1970 helped make the Partially Buried Woodshed one of the many memorial sites on campus.[2]

The work was set on fire by an unknown arsonist on March 28, 1975, burning much of the left side and causing the structure’s major collapse.[5] The University Arts Commission recommended in April that the roof and burned portion be removed [as opposed to being repaired]—mostly citing safety concerns—with the remaining walls, earthen mound, and rafters allowed to continue the natural aging process.[6] By late April, the university had much of the damaged section removed and planned to landscape the area around the sculpture as a park.[7] Smithson’s widow, Nancy Holt, visited the work on May 3, 1975, and called for its preservation.[8] A committee recommended in June 1975 that the entire sculpture be removed, citing liability concerns, though university president Glenn Olds ultimately decided to keep the remains of the sculpture in 1976. Sometime in mid-1981, the center beam fully broke, and in January 1984, the remaining wooden elements of the structure were quietly removed by the university.[9] While the School of Art hosted exhibits in 1990 for the 20th anniversary of the work’s creation, and again in 2005 for the 35th anniversary, the location of the artwork was largely ignored until Kent State University added an informational plaque to a sidewalk near the site in 2016.[10]

Finally, “Amarillo Ramp”:

Here is the initial sketch for the project:

July 1973. Robert Smithson begins work on a new project “Amarillo Ramp.” #landart #art pic.twitter.com/L95CEymYvh

— Troublemakers (@landartfilm) July 16, 2015

Here is Amarillo ramp then, as constructed:

And here is Amarillo ramp now, having decayed:

If you want to see this one, you’d better hurry up. From Texas Highways:

In 1973, when it was completed, Amarillo Ramp was a spiral pathway jutting into Tecovas Lake, an artificial body of water outside of Amarillo. It was comprised of sandstone found in the area, compacted to an ascending height of 15 feet, and measured 140 feet in diameter. Now, with the lake long since dried up, Amarillo Ramp amounts to a quirky, failing rock formation.

Stanley Marsh 3, an Amarillo arts patron, commissioned Amarillo Ramp for his vast property around the same time he enlisted the art collective Ant Farm to create the more well-known Cadillac Ranch off historic Route 66. Smithson died before the completion of Amarillo Ramp, but his widow and artistic partner, Nancy Holt, along with artist friend Richard Serra, came to the rescue and executed the project. They added but one final touch to Smithson’s design: They cast the sides of the ramp at a slight angle rather than at 90 degrees.

Make arrangements to view Amarillo Ramp by emailing the Holt/Smithson Foundation, which is dedicated to the legacies of the married artists, at ar@holtsmithsonfoundation.org. This rarely seen work comes with a personal tour guide and requires a 15-minute drive down a gravel road. What awaits on private land is a sliver of its original self and could easily be lost in the camouflage of the landscape. But it’s there, reminding us, in the service of dying, to live life before we too are just dust in the wind.

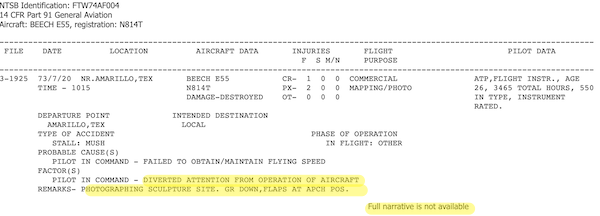

What Texas Highways doesn’t say is that Smithson had gone up in a small plane[4] to inspect the site, and he and his pilot died in a crash. Here’s the crash report:

It’s interesting to think that earth from the Ramp, plus the crash report, would constitute a nonsite. (The note that “Full narrative is not complete” is so post-modern I can’t stand it.)

One critique of Smithson’s work is that it is not “political,” which art should be. In vulgar form:

the point of art is for it to Do Politics, so you can look at it and go “wow politics” and “if only other people were as enlightened as me, to see these politics”

— let le wokisme win (@lyta_gold) July 30, 2022

Or, in more sophisticated form, from “Ecological Art: What Do We Do Now?” at, amazingly enough, Nonsite.org:

[Araeen’s’] critique of the unseeing egoism of American earth artists such as Smithson and Morris is not without precedent. What is unusual about his manifesto is its optimism despite ecological warning signs, many of which we are alerted to by artists. While Araeen rails against ego in the realm of art that focuses on nature, he claims that the idea of making land into art in significant ways remains potent. How? Through what he calls “collective work” (683), a radical transformation of human consciousness. He cites Beuys’ famous 7000 Oaks project – begun at Documenta 7 in 1982 and continued in New York – as an example of how to make planting trees “part of people’s everyday life” (682).

As NC readers know, the Earth’s requirement is not trees, but forests. More:

Many contemporary artists share Araeen’s sense of urgency. They agree that fellow artists should focus on ecological issues but also caution that this emphasis is not yet sufficiently global. Araeen’s examples of art’s ameliorative effects center on bringing water issues – specifically more widespread desalination — to the fore… Basia Irland has similarly underlined the potency of social organization and participation in her many “Gathering” works. A Gathering of Waters; Rio Grande, Source to Sea,” she reports for example, started in 1995 and “took five years to complete. Hundreds of participants were invited to put a small amount of river water into a canteen, write in a logbook, and pass these downstream to another person.

[UPDATE I am having a highly irritable reaction to Irland here, brought on by Nonsite’s framing, more than Irland’s projects themselves.] This reminds me of one of those horrid listening sessions where a consultant posts sticky notes of the attendee’s suggestions (and doubtless throws them away, having already written their report, or recycled it from another project. Forgive my cynicism.) More:

Connections were made that have been lasting, and groups are working together that never would have met otherwise. In order to participate in this project, you had to physically be at the river and interact with someone else downstream, thereby forming a kind of human river that brings awareness to the plight of this stream that is always asked to give more than it has.”

Aesthetically, I think this is hooey, and NGO-style hooey at that. I think Irland’s projects are primarily aestheticized documentation, as opposed to Capital A Art. (Implicitly my incoherent aesthetic says that art should last far beyond the milieu in which it was created, unlike, say, entertainment, socializing, or sticky notes. Objects have their own integrity that persists over historical time, regardless of whatever political use can be made of them.)

I’m sure I don’t need to further underline the themes of decay and entropy in Smithson’s work. He is, after all, deeply concerned with the material, which decays. That’s one aspect of his work that makes him the artist for the Jackpot. But there is a second, more subtle aspect of his work, and in a classic illustration of the post’s theme, I have misplaced and cannot recover the tweet that documents it. If I had the tweet, it would go in a blockquote. It’s a note to the Holt-Smithson foundation:

To Whom It May Concern:

Some kind but thoughtless students of mine recently visited “Spiral Jetty,” and brought back a gift for me: A rock they had taken from it.

Enclosed please find the rock. I am returning the rock to you, in the hopes that you can return it to the Jetty.

(There was a photograph of the box the rock came in, and the note.) In this way, Spiral Jetty, as art, was able to link unexpectedly the past and the future, in this case through acts of kindness (misplaced and, er, to be placed). We will need to be able to do this during the Jackpot just as much as we will need to be able to recognize (and mourn, and cope with) decay. The Forest Service (!!) quotes Smithson:

Nature does not proceed in a straight line, it is rather a sprawling development.

~Robert Smithson #quotes pic.twitter.com/fNatiR0gvW— Northern Research (@usfs_nrs) November 20, 2019

And, as a lemma, Nature does not proceed in a straight line down.

NOTES

[1] Nobody seems to remark on the surrealist aspect of “Spiral Jetty.” A spiral jetty is just as useful as Man Ray’s “Cadeau,” an iron with nails in the sole plate:

[2] I looked at the Holt-Smithson Foundation’s Board of Directors and didn’t see anything horrifying by NGO standards, as one might in other contexts.

[3] So as I can determine, there is no connection between Smithson’s concept of a nonsite, and Nonsite,org, edited by, among others, the redoubtable Adloph Reed.

[4] Unlike, say, Jackson Pollock; see link in note [2]. This is a joke.

I’ve always liked the idea of ephemeral art but Smithson‘s art is heartbreaking. And ultimately, his story is tragic.

Also, I once had a job testing gravel for highway construction. This post reminded me of that year.

What a great job!

I think ephemeral art is entertainment. Ars longa, vita brevis.

The sand paintings of Tibetan Buddhists and Navajos are ephemeral. In such instances I would argue that the persistence lies not in the objects produced but within the persons that produce them as handed down through succeeding generations. I suppose photographs of same, although most likely requiring less artistic knowhow and effort, might qualify as fulfilling the requirement of object persistence. Andy Goldsworthy for example produces ephemeral artworks from unrefined natural objects— branches, stones and the like, which he then photographs.

Hmmm…

“All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music.” – Walter Pater

not arguing… just a paradox that rings true to me, a musician/artist/entertainer type.

This bit about taking rocks away from the Spiral Jetty and then sending them back is intriguing. I bet the rock was not replaced at exactly the same spot it was taken from. If this happened often enough, the Spiral Jetty could creep away to wind up at a completely different lake from the one it was built at, and not, as is happening with ordinary entropy, a lake completely different from the one it was built at.

I’ve been reading this site for a while now, but I can’t exactly piece together what ‘jackpot’ is supposed to mean. Could someone enlighten me? Collapse of civilization? fascism? anarchy? bad climate change?

> Jackpot

See here.

The “Spiral Jetty” is the only major work of art by Smithson that holds much interest — for me. In my opinion, the rest of his oeuvre is at best forgettable. His work “Glue Pour” hardly competes in beauty, scale, or political message when posed opposite the many works of environmental waste and destruction created by our Corporate Elite. “Line of Wreckage” evokes the much grander and aesthetic works of various state departments of transportation as rendered in the debris walls of rock and heavy metal fencing used to reduce erosion along highway escarpments. The steps in some of these are much more interesting than the painted aluminum — and there is no comparison in the reach of their scale. The “Partially Buried Wood Shed” is far less interesting and aesthetic than any number of the derelict wooden sheds, barns, and houses dotting the countryside where I live, or some of the buildings ‘eaten’ by kudzu you can see in many parts of the South. The “Amarillo Ramp” is all too derivative of the much more attractive and interesting “Spiral Jetty”. Both works evoke the magnificent Nazca Lines in Peru or the Mississippi Mounds in the u.s.

I admit that my theory of aesthetics remains stunted at the level of the Supreme Court’s theory of pornography. Even so, I am not uncomfortable feeling mournful of the financial support that Smithson’s works required in the belief that the money might have supported and kept from starvation many other more deserving artists. In retrospect, so much of the famous and celebrated art and art concepts from the 1960s impress me most with their shallow pretentiousness. It is not sufficient to intentionally evoke images of much grander and more compelling works — many of which are unintentional and created through other causes than deliberate aesthetics. Smithson’s evocations make no compelling statements to me that were not already evident in the greater works.

Do wonder if at some point in the future, after our hubris has lead to the loss of the power grid and thus the ability to access so much of history, people will come across the spiral and wonder, much we do with Stonehenge, what religious significance it may have had.

It is an agnostic’s religious symbol: a question mark with extra curls, or perhaps a kinhin walkway.

Even now, some of us wonder about the significance of the spiral. I do not believe it compares favorably with other similar land artifacts from earlier times. It may be interpreted as telling of the declines of our present age with respect to much earlier cultures.

I do like the Spiral Jetty; I liked the freeform with the giant pods more. Here’s what I think about Smithton’s agony about entropy – he doesn’t understand it. If he did he would have not made such a regular, almost boring spiral. True art is steeped in all sorts of entropy. But Spiral Jetty is just too regular, it winds up like some dumb, senseless mechanism. If Smithson had done some slightly loopy spiral it would have had an irregular rhythm. I’m thinking like a wave function – but who can nail that down? The only entropy Sprial Jetty will endure will be a slow erosion. Which might also be nice.

Speaking of entropy, I’m reading a book on mammalian evolution and extinction, Beasts Before Us by Elsa Panciroli. It’s kind of depressing in a way: all those fantastic critters come and gone. It is perhaps a bit less so if one realizes what a remarkable and persistent shapeshifter is DNA.

The trouble there is that if an artist represented entropy directly, there would be no way to tell. The artwork would look like nothing.

I anticipate some large institutional building, possibly the Department of Media Studies, standing on a university campus with a plaque saying “Half-buried Woodshed”. Not a historical plaque — it would not be history. The building would be a Half-buried Woodshed, created by Smithson and entropy.

Q.v. Jorge Luis Borges’ The Lottery in Babylon.

I am reminded of the movie SLC punk, and it’s many fine scenes. But they aren’t alot of fun out of context.

Have Cake instead.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTTq-3lm6ck

Alpha Beta Parking Lot (Comfort Eagle, 2001)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rtlAQWENjyY

Easy to Crash (Showroom of Compassion, 2011)

Has it really been so long?

I immediately thought of geoglyphs when these ‘monumental’ works were pictured for my edification.

Many geoglyphs are astronomically aligned. The Mississippian mounds often are. Remember that the general opinion is that well over 90% of the North American geoglyphs have been destroyed in the last two centuries by farmers and town and city builders. What became town and city sites for the ‘Latecomers’ were equally alluring villiage sites for the ‘Early Peoples.’

An example; there was a very large shell mound on what is now the East San Francisco Bay shore. It survived well into the Twentieth Century. The site now hosts a shopping mall.

See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emeryville_Shellmound

If one wants to consider the transient nature of things, may I suggest a tour of many now empty shopping malls? I believe that there are some interesting websites and attached YouTube videos concerning these “thousand points of dark.” [I do wonder how consciously ironic Bush 41 was when he uttered the invert ‘doppleganger’ phrase to this in his election speeches.]

The ‘original’ phrase has a curious history: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thousand_points_of_light#:~:text=Bush%20reprised%20the%20phrase%20near,a%20thousand%20points%20of%20light.%22

I heard dennis kucinich quote the thousand points of light, what a dead end, from Bobby Kennedy.

My town was where the indians (native americans) met to potlach for the winter. They would ice fish together in peace.

What else would you do if you wanted to see tomorrow?

The claim that Smithson’s art is not “political” seems to overlook quite a bit. E.g., here’s RS in 1970:

Bye bye Lake Bonneville, we hardly knew ye.

As a semi native Utahan, I have visited the spiral jetty only once, just a couple of years ago. It was June and the water was amazingly warm. I built my own mini jetty to the side in salt-sand like other visitors had. It’s sad how far the water has retreated from it. Our lake is dying, and our politicians have been trying to make more dams and siphon more water from it still. I keep saying that we need to build a sprinkler system on the lake and we should have started the project years ago. By the time we get there, the toxic dust will probably be bad.

By the way, that side of the lake is pink because there is a difference in salinity on the north side due to the railroad building a line in the middle of the lake. It’s very striking.

Entropy. Things fall apart. The center cannot hold. Did I read the peripheral before or after I read Lambert’s review? Do not recall, but the Jackpot passage is with me every day. It is deeply sad to watch things, as we have known them, falling apart. I grew up on a farm in the middle Hudson Valley. Among many others, I have a persistent image of an immense flock of starlings wheeling in the sky. I have not seen that in many years. You need not pile dirt on a shed to watch its slow dissolution. The warped and skeletal barns and houses that dot the plains in the Dakotas and Montana serve as well. Are those inadvertent political statements? I do not think of them in that way, nor do I see Smithson’s creations as political, but I may misunderstand the connotation of political in this context. Change, entropy, is not in itself good or bad. It simply is. I think of the world in which I grew up and am sad that my grandchildren will experience a changed and it appears a more uncomfortable, less vibrant, more unfriendly, emptier world. Eliot’s line, “and the leaves were full of children” seems impossible today as the slow but inexorable avalanche that we set in motion consumes us. The shrinking of lake and river are harbingers. The constructions of Smithson punctuate them.

Henry Francis Lyte is a famous old boy of my father-in-law’s school, along with Oscar Wilde and Samuel Beckett. Lyte wrote Abide with Me while rector of Brixham, where he enjoyed a sufficiently munificent living that his rectory is now a clifftop hotel and the town church was much enlarged by his efforts and a devoted congregations’ donations.