It seemed likely that as highly speculative plays like crypto, NFTs, and SPACs crashed to earth, venture capital would be soon to follow, and not simply because some venture capital firms dabbled heavily in these bezzles.

A separate reason to anticipate that venture capital would be in world of hurt, aside from investment canaries dying in coal mines, is that venture capital fares badly when central banks raise interest rates and/or when inflation is high. Both are applicable now. The reason that venture capital crashes hard is that discounted cash flow models for enterprises that project big payoffs in later years are particularly sensitive to high interest rates. They greatly reduce the value of down-the-road returns.

Today, the Financial Times confirmed our expectation in a well-documented piece Venture capital’s silent crash: when the tech boom met reality. Those of us who learned in the dot-com era that absolutely lunatic ideas such as thinking it’s perfectly reasonable to assign ginormous valuations to companies with zero prospect of ever turning a profit, because eyeballs, can become pervasive before they finally fail. Even then then supposedly sober McKinsey took dot-com equity in lieu of fees and had to write off $200 million.

Despite giving a very solid overview, as we’ll soon explain, the Financial Times missed serious valuation abuses that gave venture capital promoters incentives to keep companies private longer.

Key sections of this important story, which I urge you to read in full. The article starts by warning that venture capital has lax valuation rules, which has allowed fund managers to put off writedowns. But:

Only companies with an urgent need for capital have been forced into a full reckoning with reality, as investors putting in new money demand an up-to-date valuation. Klarna, the Swedish buy now, pay later company, sent shockwaves through the market for private fintech companies earlier this month when it raised money at a $5.7bn valuation — 87 per cent less than its venture capital backers judged it was worth a year ago.

Yet that savage price cut merely echoed a turn that had already set in for similar companies in the public markets. Shares in Affirm, a US buy now, pay later company that went public early last year, have also fallen 87 per cent from a peak last November. Fast-growing fintech company Block is down 78 per cent, after $130bn was wiped from its market value.

Many more will have to follow Klarna’s lead before the full extent of the reset sinks in. Despite some signs that people are getting more realistic about valuations, “We don’t yet have the full puking that’s required,” says [Josh] Wolfe [co-founder of Lux Capital].

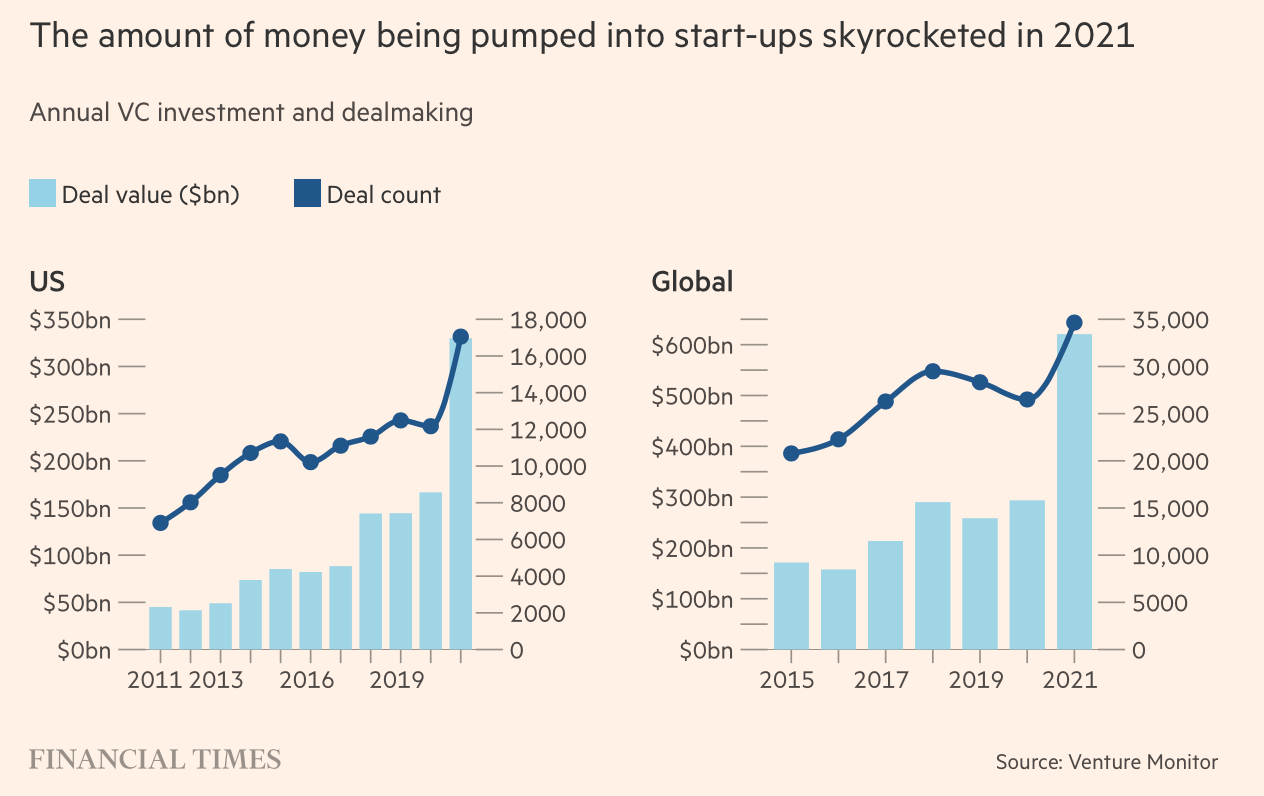

The article also points out a ginormous amount of money went new venture capital investments in 2021:

And it is a bigger money wave than in the dot-com mania:

The scale of the most recent venture boom has dwarfed that at the end of the 1990s, when annual investment peaked at $100bn in the US. By comparison, the amount of cash pumped into American tech start-ups last year reached $330bn. That was twice was much as the previous year, which was itself twice the level of three years earlier.

Note that the CPI calculator says that $1 in January 2000 equaled $1.65 at the end of 2021, so even in inflation-adjusted terms, this is twice as much money cashing young ventures as during the dot-com mania. And back then, the rapid adoption of the Internet was producing fundamental shifts in business and consumer behavior, and along with it, lots of commercial opportunities. The idea that fortunes could be made, as Amazon and Google and Facebook showed, was not entirely delusional.

By contrast, this is not an era of fundamental advances in technology. So it should hardly come as a surprise that the loft valuations were more a function of cheap money producing investors desperately chasing returns, as opposed to bona fide “innovation”.

Investors abandoned discipline and became believers:

Carried along by this immense tide of capital, many venture capitalists now admit their market was overcome by a race to invest at almost any price — though most like to claim their own funds were able to sidestep the worst of the excesses.

“If there was one word to describe it, it was Fomo,” says Eric Vishria, a partner at Benchmark Capital. The “fear of missing out” he points to brought a stampede at the peak of the market. It wasn’t just the high prices investors were prepared to pay not to miss the boat: periods for conducting due diligence were drastically shortened and protections that investors usually build in to protect their investments fell by the wayside….

As a result, according to Vishria, the venture capital industry became bloated. Many companies stayed private far longer than was usual for a start-up, drawing on private investors rather than moving to the stock market.

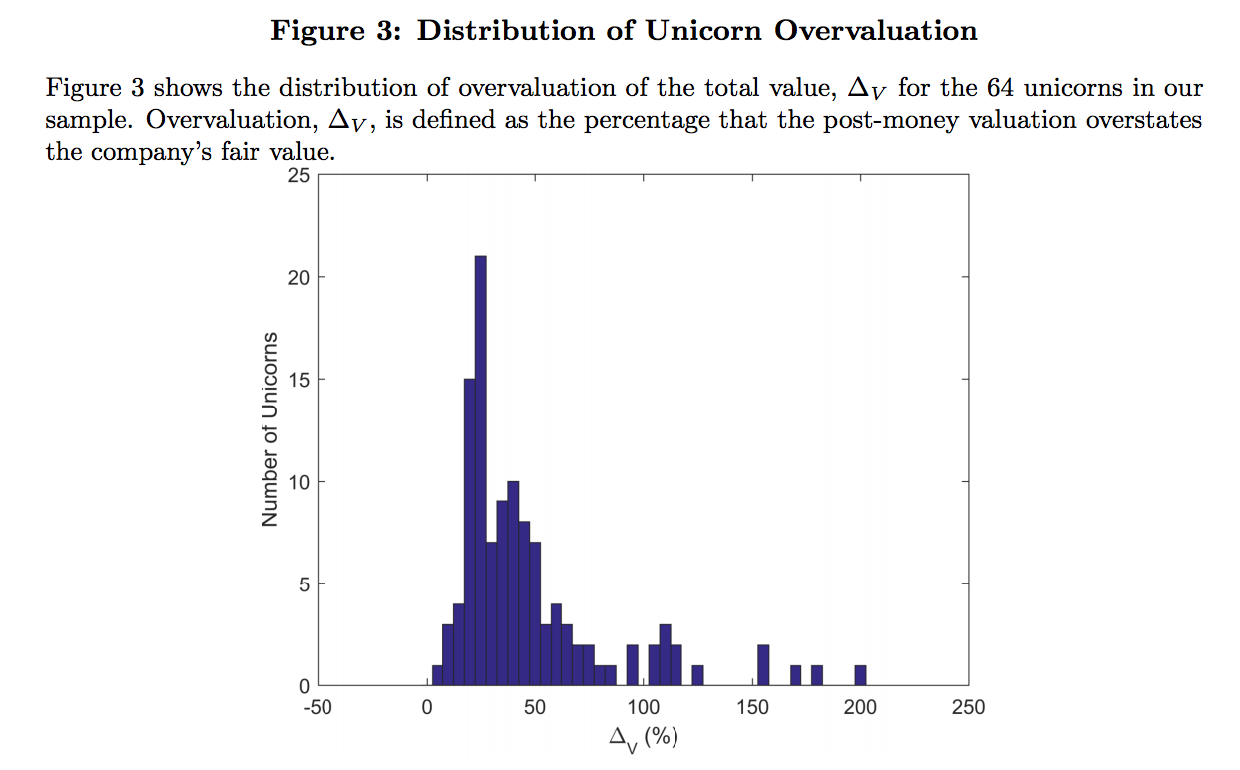

Let’s focus on the valuation issue. The pink paper missed, as did far too many late stage investors, that widely-accepted valuation rules of thumb greatly exaggerated the market value of venture capital backed companies. Unlike public companies, where the market capitalization is based on public shares, and they are all fungible (absent the occasional dual-class structure), venture deals have multiple rounds of funding, with later investors typically restricting the rights of the investors in earlier rounds to somewhat offset the typically higher nominal price paid. As we wrote in 2017, recapping a Stanford paper, Fake Unicorns: Study Finds Average 49% Valuation Overstatement; Over Half Lose “Unicorn” Status When Corrected. Key findings:

A recent paper by Will Gornall of the Sauder School of Business and Ilya A. Strebulaev of Stanford Business School, with the understated title Squaring Venture Capital Valuations with Reality, deflates the myth of the widely-touted tech “unicorn”. I’d always thought VCs were subconsciously telling investors these companies weren’t on the up and up via their campaign to brand high-fliers with valuations over $1 billion as “unicorns” when unicorns don’t exist in reality. But that was no deterrent to carnival barkers would often try to pass off horses and goats with carefully appended forehead ornaments as these storybook beasts. The Silicon Valley money men have indeed emulated them with valuation chicanery.

Gornall and Strebulaev obtained the needed valuation and financial structure information on 116 unicorns out of a universe of 200. So this is a sample big enough to make reasonable inferences, particularly given how dramatic the findings are.1 From the abstract:

Using data from legal filings, we show that the average highly-valued venture capital-backed company reports a valuation 49% above its fair value, with common shares overvalued by 59%. In our sample of unicorns – companies with reported valuation above $1 billion – almost one half (53 out of 116) lose their unicorn status when their valuation is recalculated and 13 companies are overvalued by more than 100%.

Another deadly finding is peculiarly relegated to the detailed exposition: “All unicorns are overvalued”:

The average (median) post-money value of the unicorns in the sample is $3.5 billion ($1.6 billion), while the corresponding average (median) fair value implied by the model is only $2.7 billion ($1.1 billion). This results in a 48% (36%) overvaluation for the average (median) unicorn. Common shares even more overvalued, with the average (median) overvaluation of 55% (37%).

How can there be such a yawning chasm between venture capitalist hype and proper valuation?

By virtue of the financiers’ love for complexity, plus the fact that these companies have been private for so long, they don’t have “equity” in the way the business press or lay investors think of it, as in common stock and maybe some preferred stock. They have oodles of classes of equity with all kinds of idiosyncratic rights. From the paper:

VC-backed companies typically create a new class of equity every 12 to 24 months when they raise money. The average unicorn in our sample has eight classes, with different classes owned by the founders, employees, VC funds, mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds, and strategic investors…

Deciphering the financial structure of these companies is difficult for two reasons. First, the shares they issue are profoundly different from the debt, common stock, and preferred equity securities that are commonly traded in financial markets. Instead, investors in these companies are given convertible preferred shares that have both downside protection (via seniority) and upside potential (via an option to convert into common shares). Second, shares issued to investors differ substantially not just between companies but between the different financing rounds of a single company, with different share classes generally having different cash flow and control rights.

Determining cash flow rights in downside scenarios is critical to much of corporate finance, and the different classes of shares issued by VC-backed companies generally have dramatically different payoffs in downside scenarios. Specifically, each class has a different guaranteed return, and those returns are ordered into a seniority ranking, with common shares (typically held by founders and employees, either as shares or stock options) being junior to preferred shares and with preferred shares that were issued early frequently junior to preferred shares issued more recently.

The way the VCs mislead the press and the general public is how that they assign a valuation after each round of fund-raising assuming all classes of equity have the same value.

The linchpin finding from the authors:

Equating post-money valuation with fair valuation overlooks the option-like nature of convertible preferred shares and overstates the value of common equity, previously issued preferred shares, and the total company.

Mind you, even though this study focused on unicorns, the same rampant overvaluation is likely to be found in all venture-capital-backed companies that were private long enough to have undergone, say, six or more funding rounds. Moreover, the overvaluation could well be worse in non-unicorns, since the big high-fliers would presumably be the most attractive to the late-stage investors. They would be likely to impose tougher terms on the also-rans, which would increase the post-money-valuation distortion.

As we pointed out in our 2017 writeup, it wasn’t just venture capitalists who were enabling this valuation chicanery, particularly by using devices like IPO ratchets which would further inflate post-money valuations. It was also that fiduciaries like Fidelity and T. Rowe Price that regularly invested in late-stage private deals, also fell in with the valuation hype rather than doing the hard work of a proper assessment.

So if this bubble deflates nastily, just as it did in the dot-bomb days, know that plenty of supposed professionals who should have known better very happily went along for the ride. A jaded Financial Times columnist, John Dizard, explained how this worked in 2007:

A once-in-10-years-comet- wiping-out-the-dinosaurs disaster is a problem for the investor, not the manager-mammal who collects his compensation annually, in cash, thank you. He has what they call a “résumé put”, not a term you will find in offering memoranda, and nine years of bonuses….

All this makes life easy for the financial journalist, since once you’ve been through one cycle, you can just dust off your old commentary.

And as Dizard explained, most of the incumbents will dust themselves off after a year or two of lean living and then go back to an approximation of their old normal. The ones at most risk are middle-level staffers, senior enough to be costly but not perceived to be indispensable. But even most of then land pretty well, even though not always back in the fund management game. The fact that running money is such a “Heads I win, tails you lose” game is the reason even serious bear markets don’t change behavior as much as they ought to. Investors, just like the customers of fortune-tellers, want to believe.

The starting date seems too young.

Playing around with the CPI calculator on bls.gov, it looks like the author meant to use a starting date of January 2000, not 2020.

oops, 2000, not 2020, fixing…

Crossover funds like Tiger Global burst onto the scene with billions in capital ready to be deployed, and with their low/no diligence investing model were apparently sending out 15 term sheets every week at the peak of the cycle. Doing diligence and requiring a board seat, long accepted as standard termsheet provisions, became anathema overnight as power shifted entirely to founders who pressed home their advantage against investors afflicted with serious bouts of FOMO.

The reckoning with the new reality is nothing short of brutal, down or flat rounds litter the landscape, valuation multiples have contracted sharply (saas multiples were 100x ARR last year but have now reverted down to their mean of around 5,6x ARR) and available powder (there’s apparently $250bn on the sidelines sitting in LP accounts) is being kept dry as the new trend in investor circles is to talk up staying on the sidelines and being responsible. But, and there’s a but, star VC brands like Andreessen Horowitz, Sequioa etc are still closing multi-billion dollar funds even in this environment, hinting at a shakeout in the VC space that’s going to cull some of the smaller, less recognised players. Lessons won’t be learned and once the stock market (as the terminal buyer of privately held tech companies) recovers from the current rout, it will be back to business as usual and tech startups will dust themselves off and resume their role as liquidity sponges.

As a tech dev who has interviewed with quite a number of startups over the past several years, I can say that most of these firms are built on ridiculous, niche ideas that will never generate a penny in profit, including most of the much-vaunted fintechs. And those few that have a maybe concrete-sounding business model like Revel (rent electric cars and mopeds to finance build out of charging infrastructure) will probably collapse with all the others as financing dries up.

Yes, if you’re a tech startup and you don’t have enough capital in your bank account to give you a two year runway, the likelihood of a crash is very high.

Who sells all these Unicorn Miners their picks, shovels, tents and jeans?

Big weed owes a lot of money to VC. Outside of getting listed on the Canadian exchanges, there’s limited funding for significant investment required for the startup and/or expansion of the large enterprises so they do funding rounds. Ownership’s plan is always to just get more funding to increase the valuation and hope that the operation can be sold on or will eventually be big enough to IPO on the Canadian exchange (plus the constant hope of federal legalization, they were sure when Biden was elected it would be any day, LOL). I’ve been wondering when those investors would start demanding to be paid by companies that aren’t, generally super profitable in a market they overvalued and then drove down through over production. Maybe that time is now.

Big weed is about to get creamed too, which was eminently predictable – https://www.pressherald.com/2022/07/31/recreational-marijuana-prices-dropping-as-product-floods-the-market/

The article notes that the local average price has dropped significantly and is about $9.26/gram now, which is about the same as the black marker price prior to legalization. The head of the Maine Cannabis Industry Association is quoted as saying he doesn’t expect the price to drop further since consumers aren’t demanding it, but I suspect he is talking his own book with that comment. I recently saw it on sale for about $7/gram at a local recreational store (for some reason we differentiate between medical and recreational weed still even though it’s the exact same thing), and the recreational price is usually significantly higher than the medical price.

Presumably the black market price was as high as it was due to the risk of going to jail, so one would think the price after legalization would be lower with that risk removed, however in Maine at least until recently the legal price was higher, and often much higher then the black market price. Legal dealers have got in a year or so of gouging people but that is about to end. I expect to see a lot fewer weed stores in another year or so and a lot of people aren’t going to strike it rich like they thought they would.

For a bunch of people who are supposed to be the smart guys in the room, the VC types didn’t seem to take into consideration that there’s a reason it’s called weed – it’s easy and cheap to grow, just like its namesake, and it’s been massively overproduced in the rush to cash in.

I see $99/oz here but don’t frequent the dispensaries so don’t know if that’s before taxes. At least in MI, the big weed lobbyists are working hard to end our legacy medical program (a grower can have 5 patients plus himself for a total of 72 plants) and have made some noise about ending the personal grow exemption of 12 plants/household. They know that long term they will not be able to compete with that. But they also know that many of their type are $100M+ in debt to VC for their splashy buildouts with claims they’ll dominate the market through size and reach. The full power of the federal government couldn’t stop my generation, not sure why Big Weed thinks it can stop the next one (and I’m over here offering anyone I kind of know to teach them enough to never need a dispensary).

I bet that $7 gram price will be dropping more. Here in the pacific northwest, it’s $2 or less a gram lately. You can buy cured, packaged ounces of very good outdoor-grown weed for $60, $50, sometimes even $40. With my frequent buyer card I got my last ounce for $30, a bit over a buck a gram! At these prices it hasn’t even been worth the bother to grow it.

There’s a typo in this sentence: “Note that the CPI calculator says that $1 in January 2020 equaled $1.65 at the end of 2021.”

It should be January 2000.

When someone tells you a deal is “Too good to be true”, believe them.

Venture capital in renewables is an interesting situation. Particularly the ones that build the actual utility plants. I don’t know how they structure themselves so as to avoid increases in interest rates/inflation. Seems to be a situation designed for some sort of interest rate swap. And of course an implosion by whoever thought it was easy money issuing the swap.

https://www.utilitydive.com/news/have-some-renewable-energy-an-investor-would-like-to-speak-with-you/619718/

Utility plans, in any case, are anything but unicorns. I may be very much misguided but tend to believe that with current e-prices these must be turning into milk cows.

I always love the “inflation leads to lower discounted cash flow” arguments, because they ignore the fact that, if prices in general are going up at a higher rate, future profits from these companies should be adjusted accordingly.

Of course, the future earnings estimates for these companies are all made up, so it’s an illogical adjustment applied to a mythical number. But we’re supposed to think these finance people are serious stewards of wealth…

I’ve done financial modeling for decades in all sorts of interest rate environments, including the super high interest rates of the early 1980s. You clearly haven’t.

The impact of higher interest rates on future cash flows is COMPOUNDED. Your remark is nonsensical if you understood that.

I think this is dealt with tin the idea of nominal vs real rates…

“Nominal versus Real: If your cash flows are computed without incorporating inflation expectations, they are real cash flows and have to be discounted at a real discount rate. If your cash flows incorporate an expected inflation rate, your discount rate has to incorporate the same expected inflation rate.”

Also you are investing in a project using “todays” money which is going to devalue at the inlfaion rate compounded as Yves said.

“By contrast, this is not an era of fundamental advances in technology. So it should hardly come as a surprise that the loft valuations were more a function of cheap money producing investors desperately chasing returns, as opposed to bona fide “innovation”.

Yes, the low hanging fruits have been eaten. It’s going to take more than magical thinking about the forward motion of “progress,” generations, and innovation to solve a host of problems.

Sounds to me like the model here, fund a company out the wazoo to allow it to dominate a market (Softbank) is running out of steam.

No a financial person but prices going up during inflation loses it value unless a company is raising prices because it could get away it, then that’s “value”. Is it really an illogical adjustment? Wouldn’t the investors take rising prices into account?

So venture capital also fell victim to derivatives? What’s the difference between the mountain of derivatives that caused 2008 and 12 different “classes” of equity in a VC startup – it’s no longer preferred stock v. common stock v. bonds – it’s a whole mind-numbing financial scheme to increase the volume of shares outstanding. In some sense this is like all those “rehypothecations” of collateral isn’t it? Except that the collateral is speculation to begin with.

A VC here. Active, not recovering. :-)

What the post and quotes don’t explain with a worked example is the preference “waterfall”. Imagine a waterwheel (the overshot type, where the water is introduced at the top). The first bucket to fill is the top bucket. Then the next, and so on down the wheel (our example wheel is not going to move!).

The various preference share classes replicate this. If the start up is sold for cash – “liquidity” – all the lovely moolah fills up the highest preference share bucket first, which is always the most recent investment round’s share class. The size of this preference share bucket is the amount of capital subscribed in that investment round. Then the next bucket fills, up to the amount of capital subscribed for the shares of the previous round, and so on. Any surplus after the last bucket is filled, representing the very first funding round, is payable to the ordinary shareholders (founders and staff).

So if you sell the business for 10m and your total subscribed capital across all preference share classes is 10m, 10m is paid out first according to the preference buckets. Zero is available to the ordinary shareholders.

If you sell the business for 100m and your total subscribed capital across all preference share classes is 10m, 10m is paid out first according to the preference buckets. 90m is available to distribute pro rata to the ordinary shareholders (the founders and staff).

BUT the preference shares have a little clause that, in the event of an exit, they can be converted into ordinary shares! Why would a VC do that and give up their higher place in the pecking order to go to the back of the queue? Because in the 100m exit example, receiving the relevant percentage of the 90m might be more valuable than receiving a fixed proportion of the 10m preference stack.

This is Preference Share 101, using what is called nonparticipating 1x convertible preference shares. The overall effect is that, as a founder, if you raise 10m of capital across various classes of preference share, you will have your exit top-sliced by the pref holders for the first 10m (or as much as you sell for if less than 10m!) unless you exit at a high enough valuation that the pref holders elect to convert to ords and take their pro rata.

This is the mechanism by which VC’s ensure return *of* capital before return *on* capital. Otherwise weird things can happen. Friends got rich in the dot.com days (they tell the story candidly but it is not my place to name them) because they sat next to an investor at dinner and were not looking to raise money but he basically threw low tens of millions at them for, say, 20% of the company – and without preferences. The founders never spent the money – their business was already cash generative – and when the company was acquired by Acme Inc during the dot.com bust, the company had to be stripped of cash. Their share of the cash invested was worth more than the residual value of the trading business! If the investor had used preferences, he would have got all his cash back but he ended up giving 80% of it away to the founders.

Preferences, son, the secret of my success is preferences….

In the dot.com bust, VC’s were scared of taking more downrounds and started to offer term sheets with 1.5x or even 2x preferences (and in the bottom fishing parts of the ecosystem, higher multiple preferences were seen). This meant that an exit would have to pay back 1.5x or 2x invested capital before any exit proceeds would reach the ordinary shares. Trickle-down economics, baby!

If a company raises a 100m mega round for 10% of its equity, it is worth a notional 1bn post-money (I.e. 900m pre-money plus 100m new capital). But if the 10% equity has a 2x preference, you can view the effective valuation paid by the VC as being 500m postmoney: the VC will get 200m of return on an exit, which is 20% of a billion, implying their investment of 100m bought a 20% share I.e. it was effectively at a 400m pre-money, 500 post-money.

Most of the unicorns are fake. A marginal slice of last-to-arrive capital generates a headline valuation but the majority of the shares are not worth that much. If you sold the business for the headline valuation and filled all the preference buckets, the value distributable to the ordinary shares would be much lower than their straightforward percentage of the headline valuation.

You can extend this logic so down rounds look up. If you raise 100m at 400m with a 1x preference, your post money is 500m. Now raise 200m at 600m with a 2x preference. Your old post money valuation of 500m just became 600m premoney, a 20% increase. Something to tweet about!

But your new investor is entitled to 400m off the top. So at your new post money of 800m, all your previous investors only share 400m, which is 100m LESS than your previous 500m post money. Success hurts!

Different classes of equity are not derivatives. “Options” here are not options that are separately traded but options that can be exercised in light of certain events. Had you wanted more detail on the rights of the different classes of equity, you could have skimmed the underlying Stanford paper that we summarized.

Unscrupulous entrepreneurs and credulous journalists are responsible for unicorn preference blindness. However VC fund general partners and limited partners should not be. The International Private Equity Valuation Guidelines (yes Virginia, I am not making this up) state that any security has to be valued based on its rights and all contingently exercisable rights should be assumed exercised if they are in the money. So a fund that owned Series A stock in a company which then raised a big Series B round with a higher preference would have to value the company by taking the Series B post money and then assuming a hypothetical exit and applying the preference waterfall to determine the Series A proceeds. The high preference Series B round in my example would cause a drop in the Series A valuation and should be reported to LP’s.

The only way to conceal that would be to assert that the value of the business is higher than the Series B valuation, which would lift the proceeds attributable to the Series A stock. That would be very aggressive valuation practice – a recent observable third party price should trump any nonsense with DCF’s or revenue/ EBIT multiples – but perhaps it was going on among the Softbanks and Tigers. Or I suppose disregard IPEV.

At our end, little bitty Series A investing, the great VC boom did not disturb prices that far. At least not that we would pay. What it did do, here in Europe, was increase round sizes. This was probably a good thing, European round sizes were historically too small to enable a company to hit its next valuation milestones so they would always be raising bridge rounds and going sideways.

One small note, a portfolio company received an approach from Tiger. The entire process was outsourced to Bain consulting and very fast but the diligence was very thorough – and the answer was no! :-)

Let’s not forget that government corruption may have played an important role in inflating the venture capital bubble.

The largest marginal buyer of this venture capital bubble, who was willing to pay the most obscene prices during new startup funding rounds, was the multibillion dollar Saudi and Emirati backed SoftBank Vision Fund. One might speculate that Softbank chose to overpay for particular startups as a way to bribe government officials who were investors. This might be the case because according to the NYTimes:

“In late October 2017, Jared Kushner, President Trump’s son-in-law and Middle East adviser, dropped into Saudi Arabia for an unannounced visit to the desert retreat of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who was in the process of consolidating his power. The two men talked privately late into the night. Just a day earlier, Mr. Kushner’s younger brother, Josh, then 32, was flying out of the kingdom. Jared came to talk policy, but Josh was there on business.”

Josh Kushner runs the Kushner family venture capital fund called Thrive Capital, along with co-founder Jared Weinstein a former special assistant and personal aide to U.S. President George W. Bush. Thrive was invested in many of the startups that Softbank later lavished with obscene amounts of money over a series of funding rounds. The net effect is that Thrive Capital and its private investors, whomever they may be ( your guess is as good as mine ), became phenomenally wealthy. And who knows what types of favors might have been given in return for these compensations.

So when someone decides to throw $100 billion into a market and pay prices that don’t seem reasonable, then be wary because their goal might be something other than simply maximizing investment returns.

This is very interesting. Do you have tabular data?

So when someone decides to throw $100 billion into a market and pay prices that don’t seem reasonable, then be wary because their goal might be something other than simply maximizing investment returns.

Softbank’s operating procedures whereby it massively inflates the valuations of its portfolio companies are, alongside Calpers’s corruption, a universally understood joke in the stateside VC community, to the extent that nobody bothers discussing them any more.

Softbank chose to overpay for particular startups as a way to bribe government officials who were investors.

Better to say that the bribing of government officials and powerful people is a necessary secondary effect, the main aim is to inflate the valuation of the portfolio companies. That’s the whole game. Whether for Softbank or, to a lesser extent, the likes of Benchmark Capital and others in the US, who were/are likewise involved in creating ponzis like Uber or WeWork and many others.

“It’s a big club and you’re not in it.”

To be clear, too, this works in exactly the same way as the feedback loop whereby banks have continually inflated ordinary house and RE valuations by being willing to give ever-larger mortgages so as to book ever larger profits — and RE mortgage lending constitutes 80 percent of all loans made by banks in America. And these profits then get counted towards US GDP.

So it’s not just VC, the whole system is based on these ponzi valuations.