Lambert here: Cf. Psalm 23; who are these “enemies”?

By Etienne Le Rossignol, a Research Fellow at London Business School, and Sara Lowes, Assistant Professor of Economics University of California, San Diego. Originally published at VoxEU.

Moral universalism – the extent to which individuals exhibit similar altruism and trust towards in-group and out-group members – varies widely across societies. An extensive literature has examined the determinants of levels of trust in different societies. However, we know relatively little about how trust changes as a function of social distance or, put differently, what affects the levels of trust shown to in-group members relative to those outside the group (Hruschka and Henrich 2013a, 2013b, Enke 2019, Schulz et al. 2019). This is important because the scope of moral values has been shown to affect a wide variety of outcomes – such as policy preferences, willingness to redistribute, and altruism – even more than do variables such as income, wealth, education, or religiosity (Enke 2020, Enke et al. 2021, Cappelen et al. 2022). Motivated by a rich anthropological literature, we examine how reliance on transhumant pastoralism – a traditional form of economic production in which populations seasonally migrate and herd livestock – shapes the scope of trust (Le Rossignol and Lowes 2022).

Pastoralism is a livelihood practiced by over 250 million people today. Pastoralists raise livestock such as cattle, sheep, and camels (FAO 2018). Certain groups of pastoralists undertake some forms of seasonal migration known as transhumance and are referred to as transhumant pastoralists.

Anthropologists highlight several features of transhumant pastoralism that may generate greater in-group trust and less out-group trust (Goldschmidt 1965, Spencer 2013). First, transhumant pastoralists exist in extremely challenging environments that are generally unsuitable for intensive agriculture. Undertaking seasonal migration offers the possibility of existing in these environments, but also undermines other means of managing risk. Thus, while both sedentary and transhumant pastoralists are exposed to multiple threats from the environment, sedentary groups can cope with challenging environments by constructing shelters, building fences, or forging alliances with neighbouring groups. These same risk-mitigation strategies are less available to transhumant groups, who must rely on each other to share and mitigate risk. Second, transhumant pastoralist groups are only able to reap the benefits from migrations that they and their animals survive. The migration itself can be risky, exposing pastoralists and their capital to potentially hostile groups and terrain. This incentivises transhumant pastoralists to rely strongly on their community for mutual assistance and protection.

We examine how reliance on transhumant pastoralism historically is associated with the scope of moral values today. To do this, we employ several data sources. First, we use data from George Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas, which codifies ethnographic data for over 1,200 pre-industrial societies, to construct our measure of historical reliance on transhumant pastoralism. We match this with present-day data from the Integrated Values Surveys (IVS), which has data on trust for 280,000 individuals across 97 countries, allowing us to ask: do individuals from ethnic groups that relied more on transhumant pastoralism in the past have greater in-group relative to out-group trust than others?

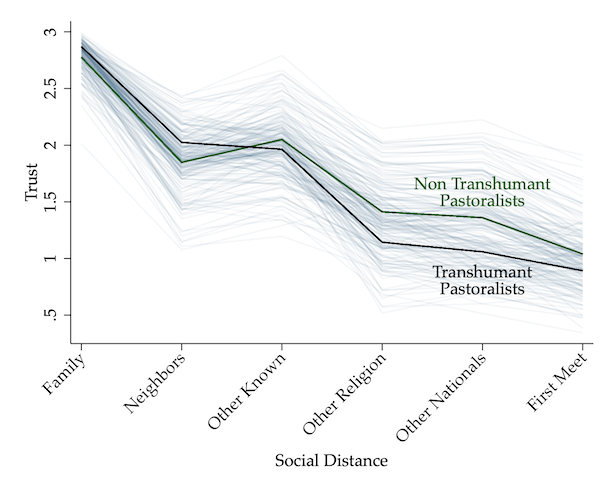

The key results are summarised in Figure 1. For each country, we plot average levels of trust as a function of social distance in a variety of other individuals, including family, neighbours, other known people, people of another religion, from another country, and people first met. Several key patterns emerge. First, in most places, individuals tend to trust ‘in-group’ members (family, neighbours, other known people) more than ‘out-group’ members. This is indicated by the general downward slope of the lines. Second, there is a lot of variation across countries in the levels of trust, as shown by variation in the overall height of the lines.

To test our hypothesis, we compare the averages for countries that relied, historically, on transhumant pastoralism (designated by the dark black line) with countries that did not (designated by the green line). We find that transhumant pastoralists have greater trust of in-group members (the black line is above the green line for the first two types of individuals) but have less trust in out-group members (the black line is below the green line for those more socially distant).

Figure 1 Trust and social distance across countries

These results – that transhumant pastoralists have more parochial trust, or alternatively, more limited moral values – are consistent if we look across countries or within countries by leveraging variation between the ancestral livelihoods of different ethnic groups residing in the same country. Our analysis suggests that the effect is very persistent. Indeed, when we analyse the scope of trust among second-generation immigrants, we find a similar pattern. Finally, we rely on an instrumental variable approach to give a causal interpretation of our results.

We then turn to better understanding the mechanisms through which transhumant pastoralism limits the scope of moral values. We draw on a theoretical literature in anthropology that suggests that climate shocks and conflict may affect the scope of trust (Hruschka and Henrich 2013a, 2013b). We show that intergroup relationships are important. The effect of transhumant pastoralism on in-group relative to out-group trust is strongest in countries where transhumant pastoralists coexist alongside other forms of economic production, such as farming. In the same vein, we find that the effect is stronger in countries where there are more conflicts as well as in regions where pastoralists are exposed to more climatic risks, such as droughts. The increased need for cooperation in regions under severe climatic and societal constraints appears to be a key mechanism explaining the observed effect.

Finally, we explore the implications of more limited moral values on economic outcomes. Using the World Bank’s Enterprise Survey data, we show that in countries with greater reliance on transhumant pastoralism, managers tend to favour family ties over performance in their promotion decisions. We also find that greater reliance on transhumant pastoralism is associated with smaller firm size, particularly for the largest firms. These results suggest that a more limited scope of moral values – a cultural trait shaped by ancestral livelihoods – may serve as a constraint on firm growth.

Re: “Thus, while both sedentary and transhumant pastoralists are exposed to multiple threats from the environment, sedentary groups can cope with challenging environments by constructing shelters, building fences, or forging alliances with neighbouring groups. These same risk-mitigation strategies are less available to transhumant groups, who must rely on each other to share and mitigate risk. ”

Both groups work together to reduce risk. They just face different risks.

Sedentary patoralists work together to keep other sedentary pastoralists, wolves- and especially farmers- out of their territory. Examples abound. I’ll only mention the US examples: the sheep vs cattle wars of the American west; the “open range” vs “sodbusters” conflicts ; and more recently the wars between gun-toting ranchers and federal officials over who gets to rent public grazing land and the number of cattle/100 acres. And don’t forget the collisions beween European settlers and natives in New England over pigs and fishing rights and between the natives who got western technology (the Comanches with their horses and guns) and the settled agriculture and herding people (eg Navaho and Pima). There was a reason why the Army scouts in the 1870s and 80s were settled indians.

Such example can be found world wide. Today in the Sudan and Chad the war between the herders and agriculturalists continues unabated.

Transhumants in Switzerland and France every summer move up into the mountain meadows. The biggest threats to the groups I’m personally familiar with, the summer cattle herders in central France, are hikers who accidentally annoy the cattle and urban liberal calling to “save the countryside”.

But the great historical fear was wolves. Look up “Beast of Gévaudan” in Wikipedia. It was a huge, old lone wolf, apparently the loser in a fight for pack dominance, who developed a taste for 10 year-old summer herding boys and other easy prey. According to the local historical markers, after an elderly six-foot-long-nose-to-tail wolf was killed, the attacks stopped. North American’s relationship to wolves was no different. In eastern Connecticut there is a historical marker where Isreal Putnam, a hero of the Revolution, made his name one winter by hunting down and killing the last wild wolf in Connecticut.

If you think 80 pound pit bulls are a problem, try to deal with a pack of 125 pound wolves. Or worse the dire wolf, the huge North American wolf exterminated as quickly as possible by the newly arrived native Americans 10,000 years ago.

In the mountains of central France, where I’ve hiked and slept rough, I’ve encoutered the local transhumant cattle herders. One night I kept hearing the “chug, chug” of a small engine. At 4:00 am I got up, packed my tent and investigated. It was a herder, a young woman, who spent the hours after midnight with a small, gas-powered milking machine, milking her herd of cows for the milk she was making into the delicious local cheese. The tradition continues… without wolves.

The French made a piquant and energetic film loosely based on the Beast of Gevaudan, which is worth a look.

Dire wolves were specialized hunters that probably died out from lack of food as the large animals that they hunted died out roughly 12,000 years ago. Their smaller relatives are more general hunters.

Modern wolves avoid people and very, very rarely bother people aside from eating sheep, which is why ranchers and herders go exterminist on them. When is the last time anyone has gotten hurt by a wolf? Their supposed dangerousness is (mostly) propaganda especially as the average wolf is too smart to want to get people with their guns attention. Honestly, I think I have more to fear from Canis familiaris than Canis lupus.

Now, bears though. Grizzlies have been known to hunt and eat people. Any animal that has the ability to unpeeled the car or bust open the door to the kitchen for my food gets my greater concern. Mountain lions have hunted people as well even in California. And they are probably much more likely to surprise a person.

OK they’re economists, the question is, what answer did they start with?

I’d be extremely curious to see what list of countries are captured by “transhumant pastoralists”, since the gist seems to be that these countries people are parochial, nepotistic, with “limited moral values” and don’t have supersized corporations running them.

It seems like a study based on a spurious correlation, tied to a very in-the-moment moral reading of factions in geopolitics. But I could be wrong, perhaps the list of transhumant pastoralist countries that they worked with includes countries the US/UK approves of.

Astute and well put. The irony is satisfying, isn’t it?

Thank you. Made my morning.

In short, gibberish.

I bet they get to watch top predator carnivores peering upon the 4×2 from water hole to food repeat. Quickness, Speed and Courage!

Where’s Hemingway when you need TR? Where’s TR when you need CIA Bush Kennedy and Nixon? Sniff Sniff. Gab away group