Yves here. Wolf does the very important service of showing that (so far) the Bank of England intervention in the gilts market is much smaller than the press reports would lead you to believe. However, there’s also a lot of consternation as to why the Bank is engaging in easing in the midst of a tightening cycle.

In fairness, it’s not as if the Bank had any control over the recklessly stimulative and wealthy-enriching Truss/Kwarteng mini-budget that set gilts into a mini-meltdown. The Bank is also contending with aggressive interest rate increases by the Fed, which puts other central banks in the position of importing inflation (via further currency depreciaition) if they don’t keep pace. The Bank also may not have been sufficiently cognizant that British pension funds took greedy leveraged positions and were wrongfooted. If the UK is much like the US, large pension funds are close to unregulated so it’s not as if they can be prevented from running lemming-like into dodgy fads.

And the Bank relying (again so far) more on posturing and not as much as expected on actual buying does show some finesse. We’ve seen this sort of thing sometimes in central bank responses to crises, with a noteworthy version when Mario Draghi calmed rattled investor nerves by announcing the OMT…which amounted to nothing new, but was merely a rebranding of existing authorities.

I hope to give this a longer-form treatment, but the short version is that QE is not a form of monetary stimulus that is directed at the real economy. Its role in the financial crisis was to allow central banks to manipulate the longer end of the yield curve, as well as (in the US case) lower the spreads of high quality mortgages over Treasuries. That helped shore up housing prices and also indirectly provided some economic stimulus by facilitating refis.

However, generally speaking, particularly for QE directed at government bonds, QE is an asset swap. It’s not as if retail bond holders are going to tender bonds in QE. And the professional investors that do won’t and can’t run out and use the cash they get on real economy spending. They’ll go buy other financial assets. So QE does not stimulate the real economy much if at all, but does goose asset prices, which has in the long run distorted the capital markets (unnaturally high asset prices promote speculation rather than real economy investment).

Mind you, I do not want to sound as if I am praising the Bank of England. Raising interest rates is a lousy way to handle inflation cause by supply shocks, significantly Covid-induced labor shortages, Ukraine-sanctions-induced energy price increases, and food inflation. QE is a bad policy that central banks adopted uncritically, copying the Fed. I am merely saying the Bank of England handled this particular nasty juncture better than it appears….but that’s not saying all that much. It remains true that the combination of policies is confusing to investors when central banks are big believers in managing expectations.

By Wolf Richter, editor at Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

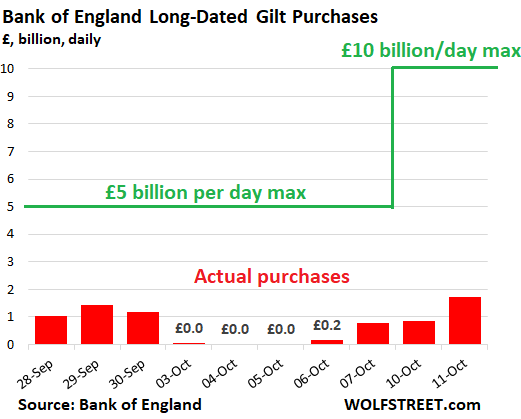

The Bank of England announced on September 28 that it would buy up to £5 billion per day in long-dated government bonds “to help restore market functioning and reduce any risks from contagion.” This was hugely ballyhooed as a “pivot” on the internet and in the US financial media. Yesterday it came out with an even more hugely ballyhooed announcement that it would double its potential bond purchases to £10 billion per day for the rest of the week. And today, it came out with an even more hugely ballyhooed announcement that it would “expand” the bond purchases. Throughout it maintained that it would “cease all gilt purchases” on Friday, October 14.

And yet, despite all the hoopla, the BOE has actually bought just a small fraction of the bonds that it said it might buy. In total, since September 28, the were 8 days of “up to £5 billion” per day in purchases and 2 days of “up to £10 billion” per day, for a total of £60 billion.

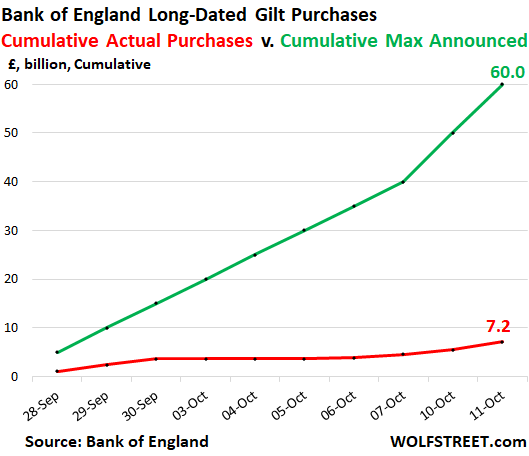

And yet… through today, it purchased only £7.2 billion in total over the entire 10-day period, with four days of zero or near-zero purchases. It purchased only 12% of the amounts it said it might purchase.

The chart shows the huge and growing gap between its cumulative purchases (red line) and its cumulative announced potential purchases (green line). The actual purchases were in effect minimal so far:

The BOE is caught between 10% inflation it needs to crack down on with big rate hikes and lots of QT and a crisis over derivatives that leveraged UK pension funds blew their brains out with.

The relatively puny amounts of actual purchases show that the BOE is trying to calm the waters around the gilts market enough to give the pension funds some time to unwind in a more or less orderly manner whatever portion of the £1 trillion in “liability driven investment” (LDI) funds they cannot maintain.

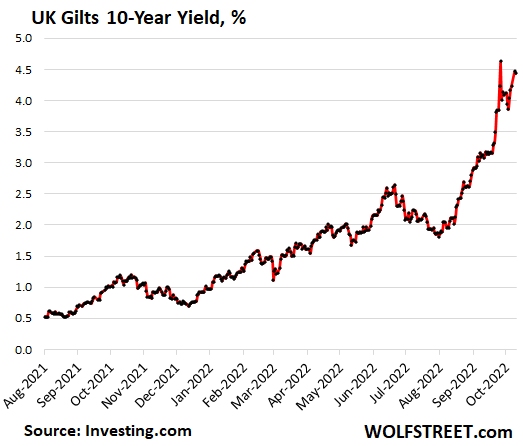

The small scale of the intervention also shows that the BOE is not too upset with the gilts yields that rose sharply in the run-up to the crisis, triggering the pension crisis, and have roughly remained at those levels. The 10-year gilt yield today at 4.44% was roughly unchanged from yesterday and just below the September 27 spike peak.

And it makes sense to have these kinds of yields in the UK, and it would make sense for these yields to be much higher, given that inflation has spiked to 10%, and yields have not kept up with it, nor have they caught up with it. And to fight this raging inflation, the BOE will need to maneuver those yields far higher still:

So today, BOE Governor Andrew Bailey, speaking at the Institute of International Finance annual meeting in Washington D.C., warned these pension fund managers that the BOE will only provide this level of support, however little it may be, through the end of the week, to smoothen the gilt market and give the pension funds a chance to unwind in a more or less orderly manner the portions of their LDI funds that they cannot maintain.

“My message to the funds involved and all the firms is you’ve got three days left now,” he said “You’ve got to get this done.”

The Wall Street hype organs and trolls had been swarming all over the internet and the media, trumping up the BOE’s “pivot,” and that the Fed would pivot next, and yada-yada-yada. So now, the BOE not only didn’t pivot, confirming what it had said all along, but also dished up an ultimatum to the pension funds.

The BOE has been in communications with the pension funds, and with the investment banks that sent out the margin calls to the pension funds, since before the crisis erupted into public view. So we can assume that the pension funds and investment banks have known about the finality of the bond purchases, that the end-date as announced on September 28 would stand, though they lobbied hard for extending it through the end of October. Bailey’s message today surely is no surprise to them.

But it was a surprise to the stock markets in the US that were still dreaming about the wondrous BOE pivot that would be the precursor of the Fed pivot or whatever.

At some stage, TPTB will want and arrange a massive crash. It is survival of the fittest. Apart from nayhting else, it has been baked in for decades, but ZIRP prevented the markets correcting.

What is the point in amassing all the genuine tomato liquidity, if all the income producing assets are all at inflated prices?

Cut the legs out from under. Pull the plug and let the liquidity drain, to see who is naked and who margined to the hilt. Then watch them all die, except for a select few.

Then, spend and cherry pick, not forgetting the genuinely new technologies that have been suppressed as they threatened the investments of many decades in what will piously be opined to be obsolete, once most of the ‘ducks are in a row’.

Most neoliberal governments are willing to bail out the assets the pensions funds invest in. The pension funds themselves, not so much…

Makes me think of Adam Curtis’ claim that come the 90s the pension funds no longer needed the raiders as they had learned how to asset strip on their own.

QE is not a form of monetary stimulus that is directed at the real economy. Its role in the financial crisis was to allow central banks to manipulate the longer end of the yield curve

I understand the individual words in this snippet. If I wanted to understand its meaning and implications, what source would anyone recommend I read?

I am not totally comfortable with my own understanding of

Financial shenanigans. I do follow wolf street web site daily.

Read what he has to say as well as the comments. Slowly but surely, the mud gets clearer.

You can do a search on ‘Quantitative Easing’ and the effect on interest rates.

It just means banks printed money and bought long-dated UST and MBS, thereby driving rates lower. The price of a bond moves inversely to the “coupon” or interest rate it carries. When the price is bid up, the rate goes down.

No, it means that precisely the thing they didn’t do was print money.

What’s he’s trying to say: Quantitative Easing meant that the Federal Reserve “bought” (more on the scare quotes in a sec) longer-dated US Treasury Bonds from banks. This stimulation of demand for bonds by the fed led to their price going up (and yields going down). When 10-year yields go down, a lot comes with it – rate of bank loans, rate of fixed-rate mortgages, etc.

So by “buying” bonds from banks, the Fed is able to Rube Goldberg their way towards making it more desirable for banks to lend instead of sit in treasuries, and easier for people to start up businesses, get a mortgage, or refinance, etc.

Okay, so the square quotes – the Fed isn’t buying anything. They take the treasury bonds off the balance sheet of the bank, and they say, here are some bank reserves denominated in USD. Now banks don’t actually get to deploy their bank reserves as lendable dollars. They sit inert with the Fed.

The other argument in favor of QE is that there are “portfolio effects” – now that the Fed has taken away a bond from a bank, the bank now has “reserves” at the Fed and can go out and make riskier loans that will generate a higher return. Except nothing like that happens…all the banks have typically done is go back into the market and buy another treasury to replace the one the Fed took away. And THAT continued buying of bonds drives down the interest rate.

I read that and I half think I understand it and at the same time I get an intense feeling of surreality. I experienced the same feeling as a teenager when I realised that we(?) had decided that a decorative but otherwise not-very-useful metal (until electronics) was about the most valuable thing we could possess and that some people would kill for.

GOLD is universally valued because it is inherently valuable.

It is inherently valuable because it is inherently BEAUTIFUL.

The structure of cosmic REALITY has more than four dimensions.

One of those dimensions is to be called KALOS (BEAUTY).

Except gold isn’t universally valued.

I suspect a major benefit was that one could stick gold in a hole for a decade, and still find it intact afterwards.

A personal take of mine is that coins started as weights, because once you start digging into ancient payments they sooner or later end up being based on weight.

Then at some point it became easier to just tally up a number and pass them around, because the local rulers had been able to maintain the weights for so long and so many had been made over that time.

That said, Graeber pointed out that debt preceded coinage. After all, when a community is small enough, that everyone is on first name basis, it becomes easy to agree to pay in grain come harvest season for the chicken slaughtered today.

And even then the most used coin in say Rome was copper based. Silver and gold was used for larger trades, often involving the Silk Road. A Roman silver coin was supposedly found in a Japanese temple wall in the present day.

Coinage started as credit markers. The debt and credit were what had worth, not the object used to represent them.

This is correct — debt precedes coinage. In fact, debt precedes writing, beginning as it does with temple ledgers in the Bronze Age, and the units recorded are weights and/or measures.

Coinage comes quite a bit later (preceded by weights of silver for “international” trade) and is associated with imperialism and force projection.

I suspect a major benefit was that one could stick gold in a hole

I am in general a landscraper by profession, and I’ve always got my eye out…what I’ve mostly found is marbles. Some really cool ones. The occassional penny or dime…I had to break up an entryway sidewalk once that had much of a rambler in it…steering column, shocks, steering wheel, tie rods…thankfully, no engine…

All coins since the Lydians came up with the concept were pretty much based on uniform weights, it wasn’t as if you could have variance.

The fledgling USA so screwed to pooch early on with Continental Currency* that it took 80 years for the Federal government to issue paper money again.

Every USA gold coin from 1795 to 1838 actually contained more in gold value than the actual face value, as we had to prove ourselves worthy.

* our first of 2 hyperinflation episodes

Why do that bring to mind the cobra effect?

The “real economy” likely is what us little people are doing every day. Buying goods and services. The QE in 2008 and 2020 that sent the Fed balance sheet skyrocketing helped Wall Street more than it did for the little guys.

What finally helped the little guys were the fiscal policies like the Economic Impact Payments in 2020 and 2021, the unemployment compensation payments (and non-taxability of up to $10K) in 2020, the totally refundable and expanded Child Tax Credit in 2021, the expanded Earned Income Credit for 2021, and to some extent the small business loans. All these were very effective in getting money to the people who actually spend it on goods and services.

That money gets spent (and multiplied through the money multiplier) instead of sitting on balance sheets and pushing down interest rates that then help push up asset prices like stocks and housing.

Err, the money multiplier is A grade crock…

give a $1,000 to a poor person and a $1,000 to a millionaire. I guarantee you that money the poor person gets circulates more than the money given to a millionaire.

A lot of voices (mostly from the left) are criticizing the BoE for creating such a storm with its comments, but I’m inclined to think that Yves is right – it’s a deliberate policy of acting tough to try to stop panic moves in the market. The problem is that its now a well known game, so it may have lost its ability to shock people into action (or non-action, as the case may be).

Whichever way you look at it, UK markets are in an unholy mess. Looks like pensions have been caught with their pants down at the worst possible time, and even the most devoted Tories in the City have no faith whatever in the current government to act appropriately. At least during the last big crises, the PM and Chancellor, despite being Labour, had some grudging respect from the City.

Apparently, the shock wore off rather quickly. Buried deep in yesterday’s FT was an angst in my pants piece about Gilt interest rates doing a vicious u-turn and heading upward. There was even a mention of the BOE buying “high-grade” corporate bonds. There must have been much stirring in the somnolent land of the zombie corporation. Is the IMF on the way?

Of course the question that goes unasked let alone answered is why have these private pension schemes at all when they end up having to be bailed out one way or another by the sovereign anyway?

It’s all about grift and “jobs for the boys,” eh?

I always sort of assumed, without really worrying about it, that ‘GILTS’ was an acronym. I didn’t realize it was because the original hardcopies that were issued had gilt edges.

‘And yet… through today, it purchased only £7.2 billion in total over the entire 10-day period, with four days of zero or near-zero purchases. It purchased only 12% of the amounts it said it might purchase.’

Slow-walking something that they don’t believe in and have no confidence of it working?

Well, now. The US TIPS bond market is having quite the day today as well. Today, traders out of JP Morgan have just noted that: “Believe it or not…Like nothing is trading. We’re the biggest linker market in the world…But everyone is scared apparently.”

So, this might be some contagion from the conventional Gilts & Linker market going haywire over here. UK 30 year conventional Gilt bonds have hit over 5% today. And for the inflation-linked (“linkers”) it’s almost like there was zero intervention at the more mediumish part of the curve (so 2030 – 2052). Interestingly the ultra long end linkers are actually holding up (2055 – 2073), which is where stress was previously (and where LDI managers got margin calls due to the move of their long-end bonds). Possible BoE intervention in the ultra long-end again??

I saw mentioned on Twitter that this was the biggest round trip in the shortest period of time in over 200 years of Gilt trading in the UK. I’ve been around over 20 years and this is nuts. A totally dysfunctional gov’t bond market.

It would appear Yves’ clown-radar is not working because the BoE has managed to reverse itself intra-morning (not even intra-day!). It is all very confusing.

https://www.ft.com/content/eb5baddb-f3bf-4558-b055-b7cb1a71bc2e

“Schrodinger’s BoE says it’s definitely not going to not stop buying bonds. All clear?”

Bailey seems out of his depth. He may be putting out a small technical fire with a bucket of sand but summoning a dozen fire engines to deliver it and then announcing he will be turning the sprinkler system off in future is not reassuring Mr Market.

For crying out loud…

A clear statement would be “we’re going to stop buying bonds. Period.”

I try to follow all the stories about gilts, t-bills, yields, derivatives, puts, calls, etc., but overall I feel I don’t have a good background on where all these piece are placed, and how they fit together. Can anyone recommend a decent book on fundamentals of modern market trading?

I have a PhD in quantum chemistry, so I’m not scared of maths.

Brian Romanchuk has some good stuff (and some books for sale) at his Bond Economics Blog

http://www.bondeconomics.com/

Thanks, eg!

My interpretation was that the Bank of England didn’t have to buy very much to get the market reaction they were looking for precisely because the major players all know that getting in front of that train is suicidal.

Some info from prospective LDI managers/advisers which send one down some for the curiouser.

https://www.nnip.com/en-INT/professional/insights/articles/leverage-in-ldi-a-wonderful-servant-a-terrible-master

https://analystprep.com/cfa-level-1-exam/fixed-income/portfolio-duration-limitations/. (some assumptions embedded here?)

https://redington.co.uk/how-to-manage-ldi-collateral-efficiently/. (nice pitch)

https://redington.co.uk/what-is-liability-driven-investment-ldi/

https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/investmentspensionsandtrusts/bulletins/fundedoccupationalpensionschemesintheuk/januarytomarch2022/pdf. (Hmmmm …. public? Funded. Unfunded?)

The whole sorry debacle is a product of the herd mentality of the parasitical UK investment consultancy industry. Pension schemes were induced to become a mix of highly illiquid assets (“patient capital”) and a liquidity-light concoction of gilts, IL gilts, swaps, repos, and reverse repos designed to match their liabilities – providing nothing bad ever happened. Of course, this is the sort of intellectual edifice that the regulators should be – but are entirely incapable of – regulating effectively.