Yves here. I do plan to Say Something about Bernanke, who appears to have been awarded a Swedish Central Bank counterfeit Nobel Prize for intellectually plagiarizing Hyman Minsky. But we need to deal with current sins of central banks and bankers again, namely doing harm to the economy (as in real people and enterprises) for the benefit of financiers. This piece explains why they have such misplaced confidence in their snake oil.

By Anis Chowdhury, Adjunct Professor at Western Sydney University and University of New South Wales (Australia), who held senior United Nations positions in New York and Bangkok and Jomo Kwame Sundaram, a former economics professor, who was United Nations Assistant Secretary-General for Economic Development, and received the Wassily Leontief Prize for Advancing the Frontiers of Economic Thought. Originally published at Jomo Kwame Sundaram’s website

The dogmatic obsession with and focus on fighting inflation in rich countries are pushing the world economy into recession, with many dire consequences, especially for poorer countries. This phobia is due to myths shared by most central bankers.

Myth 1: Inflation Chokes Growth

The common narrative is that inflation hurts growth. Major central banks (CBs), the Bretton Woods institutions (BWIs) and the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) all insist inflation harms growth despite all evidence to the contrary. The myth is based on a few, very exceptional cases.

“Once-in-a-generation inflation in the US and Europe could choke off global growth, with a global recession possible in 2023”, claimed the World Economic Forum Chief Economist’s Outlook under the headline, “Inflation Will Lead Inexorably To Recession”.

The Atlantic recently warned, “Inflation Is Bad… raising the prospect of a period of economic stagnation or even a recession”. The Economist claims, “It hurts investment and makes most people poorer”.

Without evidence, the narrative claims causation runs from inflation to growth, with inevitable “adverse” consequences. But serious economists have found no conclusive supporting evidence.

World Bank chief economist Michael Bruno and William Easterly asked, “Is inflation harmful to growth?” With data from 31 countries for 1961-94, they concluded, “The ratio of fervent beliefs to tangible evidence seems unusually high on this topic, despite extensive previous research”.

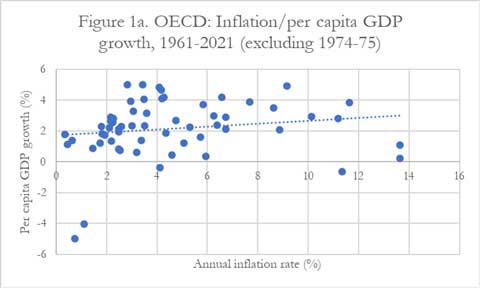

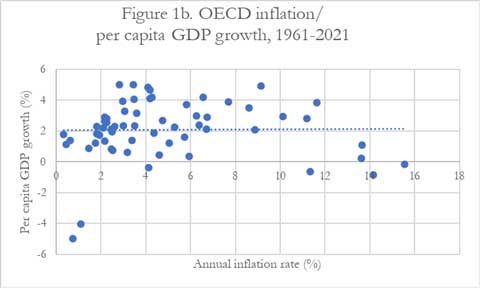

OECD evidence for 1961-2021 – Figures 1a & 1b – updates Bruno & Easterly, again contradicting the ‘standard narrative’ of major CBs, BWIs, BIS and others. The inflation-growth relationship is strongly positive when 1974-75 – severe oil spike recession years – are excluded.

The relationship does not become negative even when 1974-75 are included. Also, the “Great Inflation” of 1965-82 did not harm growth. Hence, there is no empirical basis for setting a particular threshold, such as the now standard 2% inflation target – long acknowledged as “plucked from the air”!

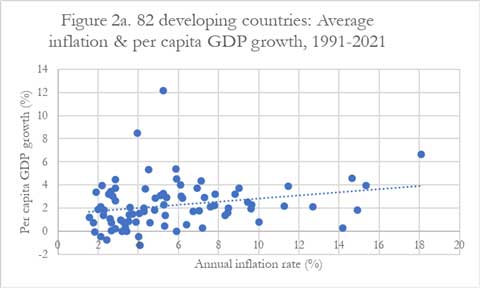

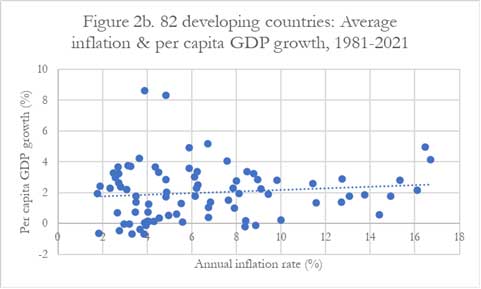

Developing countries also have a positive inflation-growth relationship if extreme cases – e.g., inflation rates in excess of 20%, or ‘excessively’ impacted by commodity price volatilities, civil strife, war – are omitted (Figures 2a & 2b).

Figure 2a summarizes evidence for 82 developing countries during 1991-2021. Although slightly weakened, the positive relationship remained, even if the 1981-90 debt crises years are included (Figure 2b).

Myth 2: Inflation Always Accelerates

Another popular myth is that once inflation begins, it has an inherent tendency to accelerate. As inflation supposedly tends to speed up, not acting decisively to nip it in the bud is deemed dangerous. So, the IMF chief economist advises, “Don’t let inflation ‘genie’ out of the bottle”. Hence, inflation has to be ‘nipped in the bud’.

But, in fact, OECD inflation has never exceeded 16% in the past six decades, including the 1970s’ oil shock years. Inflation does not accelerate easily, even when labour has more bargaining power, or wages are indexed to consumer prices – as in some countries.

Bruno & Easterly only found a high likelihood of inflation accelerating when inflation exceeded 40%. Two MIT economists – Rüdiger Dornbusch and Stanley Fischer, later International Monetary Fund Deputy Managing Director – came to a similar conclusion, describing 15–30% inflation as “moderate”.

Dornbusch & Fischer also stressed, “Most episodes of moderate inflation were triggered by commodity price shocks and were brief; very few ended in higher inflation”. Importantly, they warned, “such [moderate] inflations can be reduced only at a substantial … cost to growth”.

Myth 3: Hyperinflation Threatens

Although extremely rare, avoiding hyperinflation has become the pretext for central bankers prioritizing inflation prevention. Hyperinflation – at rates over 50% for at least a month – is undoubtedly harmful for growth. But as IMF research shows, “Since 1947, hyperinflations in market economies have been rare”.

Many of the worst hyperinflation episodes in history were after World War Two and the Soviet demise. Bruno & Easterly also mention breakdowns of economic and political systems – as in Iran or Nicaragua, following revolutions overthrowing corrupt despotic regimes.

A White House staff blog noted, “The inflationary period after World War II is likely a better comparison for the current economic situation than the 1970s and suggests that inflation could quickly decline once supply chains are fully online and pent-up demand levels off”.

Myth 4: Evidence-Based Policymaking

Central bankers love to claim their policymaking is evidence-based. They cite one another and famous economists to enhance the aura of CB “credibility”.

Unsurprisingly, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand promoted its arbitrary 2% inflation target mainly by endless repetition – not strong evidence or superior logic. They simply “devoted a huge amount of effort” to preaching the new mantra “to everybody who would listen – and some who were reluctant to listen”.

The narrative also suited those concerned about wage pressures. Fighting inflation has provided an excuse to further weaken workers’ working conditions and pay. Thus, labour’s share of income has been declining since the 1970s.

Greater central bank independence (from the executive) has enhanced the influence and power of financial interests– largely at the expense of the real economy. Output and employment growth weakened as a result, worsening the lot of the many, especially in the global South.

Fact: Central banks Induce Recessions

Inappropriate CB policies have often slowed economic growth without mitigating inflation. Hawkish CB responses to inflation can become self-fulfilling prophecies with high inflation seemingly associated with recessions or growth collapses.

Before becoming Fed chair, Ben Bernanke’s research team concluded, “an important part of the effect of oil price shocks [in the 1970s] on the economy results not from the change in oil prices, per se, but from the resulting tightening of monetary policy”.

Thus, central bank interventions have caused contractions without reducing inflation. The longest US recession after the Great Depression – in the early 1980s – was due to Fed chair Paul Volcker’s 1979-81 interest rate hikes.

A New York Times opinion-editorial recently warned, “The Powell pivot to tighter money in 2021 is the equivalent of Mr. Volcker’s 1981 move”, and “the 2020s economy could resemble the 1980s”.

Fearing an “extremely severe” world recession, Columbia University history professor Adam Tooze has summed up the current CBs’ interest rate hike frenzy as “the single most dramatic simultaneous tightening of monetary policy ever”!

Phobias, especially if based on unfounded beliefs, never offer good bases for sound policymaking.

Nobel price is not so nobel anymore.

Bernank’s great insight in one sentence: ‘under a paper-money system, a determined government can always generate higher spending and hence positive inflation’.

Positive inflation? Maybe that is the point. At the risk of going over my skis, I have for decades seen how central banks are comfortable with inflation, especially when it reduces worker’s wages and conditions. But the one thing that they do not ever want to talk about or tolerate is ‘deflation’. That would require them worshiping in another church altogether and I sometimes wonder if it is a matter of how deflation would decrease the assets of the wealthy. Hell, I am the sort of guy that questions the need of having central banks at all.

This is the meeting when Yellen convinced the fed that money should be debased by 2% a year by adopting a 2% inflation target.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomc19960703meeting.pdf

Feel free to read her long rambling discussion. But this is her main argument:

“…Second, and to my mind the most important argument for some low inflation rate, is the “greasing-the-wheels argument” on the grounds that a little inflation lowers unemployment by facilitating adjustments in relative pay in a world where individuals deeply dislike nominal pay cuts…”

Even Keynes considered moderate inflation preferable vs deflation.

So you prefer the free market approach to setting interest rates?

Doesn’t inflation decrease the value of debt though? What if I could pay off my entire mortgage for the price of a loaf of bread?

An Argentine Peso is currently worth about 1/200th of its value in 2000 when measured against the almighty buck, roughly similar to the fall in value of the Mexican Peso from the late 1970’s to early 1990’s.

If you had a 30 year fixed mortgage (I have no idea how real estate works there) on a house in Buenos Aries you bought after the turn of the century, mortgage payments would be an appealing joke, a slender scintilla.

Heavy inflation would work the same in the USA with the boogieman in the bargain being that property taxes would be worth nothing as well, both by the owner paying them and the county receiving them, so expect no services to speak of, but lots of paid off homes.

…so then it’s the utilities services that go through the roof. A surban home without affordable water and power is just a hut :) .

Well, serfs should expect to live in huts. It’s “The Natural Order of Things.”

Tentative new Neo-liberal rules:

1) Because Markets.

2) Go die.

3) Hierarchy of ‘The Valued.’

Yeah, there’s that too, unexpected perks…

…and fughed about new construction

If we do hyperinflate somehow (there have been essentially no instances of hyperinflation in this here digital age, hmmmm) expect to see a real estate listing like this in LA:

Pacoima fixer upper: a less than charming 2/1 SFH on the wrong part of a bad town… a handyman’s whet dream and then sum, sold as-is:

$345 million

Depending on where you live (of course), the property taxes are probably adjusted on a fairly regular basis–some even annually–to reflect the current market value of the property, as calculated by recent sales, which yield a percentage increase that’s applied to all properties. I’m in NYC, so naturally this is a very complex calculation the result of which is habitually disputed by large property owners, resulting in turn in an adjustment for them, resulting in another and predictable turn in small property owners bearing the brunt of the adjustment for higher market values. So your property taxes can easily go up in tandem with escalating values, whether or not you sell your house. And house price inflation is typically, IIRC, higher than inflation however measured.

So (again, depending on where you live, and you’re in California where you have Prop 13, which freezes property tax on residential property IIRC) the boogyman gets your property taxes. Probably at a higher-than-inflation rate (depending on how efficient the tax adjusters are).

Just to further complicate an already complicated mess, property taxes used to be fully deductible (offsetting inflation to a certain extent), but the deduction (which now includes state income or sales taxes) is now capped at $10,000. I do my own taxes, but boy it’s painful.

Prop 13 doesn’t completely freeze the tax but does impose a maximum increase of 1% per year. Yes, same here in CA, the loss of the fed deduction was painful, a one-two punch following the increases in healthcare costs with the ACA.

You assume countries with high inflation have fixed-rate mortgages, which most countries don’t.

So, it’s not going to be a slender scintilla but rather a good 2×4 over the head.

As long as wages go up with inflation and you continue to get them, then yes, inflation decreases the value of debt.

Problems occur when your wages are stuck and what you once spent on your mortgage, necessity now dictates you spend on food. That sort of thing.

Or, when the business that you work for is broken by energy costs, as is happening now all over Europe and you simply cease getting wages. For those with money, your debt is worth less, for you it’s become unbearable.

The situations you describe are the kind that reliably produce torches and pitchforks.

The sheeple in this country don’t know what torches and pitchforks are let alone on how to wield them.

Nor do we endorse that method of settling differences. Remember that “trial by combat” is a fictional device.

It seems MMT always comes up when government stimulus is needed, but on the flip side when inflation is out of control (and MMT says tax the excess money back) it is never mentioned?

The standard MMT response (as set out by Stephanie Kelton, perhaps others disagree) is that less public spending and more taxes should be the response if inflation is due to the economy being too hot.

Kelton as I understand it argues in her substack and in interviews that current inflation is primarily due to high energy an input costs and as such monetary and fiscal responses are largely useless or will cause more damage than harm. Policy should focus on the supply side – i.e. pushing down the cost of energy through active intervention and smoothing out supply chain issues.

Ding.

The price inflation is thanks to COVID and Ukraina playing havoc with supply chains.

We had a decade of near zero interest rate and inflation was never a worry, then a one two of war and pandemic and off to the the heavens it goes.

MMT is a bit of a brain twister because it flips the typical government thinking of taxing before spending on its head. Meaning that money comes from government spending first and foremost, and then the pool gets regulated via taxation.

This vs the current reality where money is largely a product of private bank lending (something that for example Steve Keen will talk about in length).

High prices are the cure for high prices, as the saying goes, and this goes double for ‘inflation’ that is caused more by supply chain disruption and artificial shortages, like OPEC+ supply cuts.

Central banks working off wrong assumptions about cause, could cause a financial crisis, a major depression or any number of other ills.

This might prove to be the worst time in recent history to apply brakes. The economy was already slowing when they started hiking.

More specifically, MMTers really like countercyclical tax and spending programs, like unemployment insurance. Spending goes up when times are bad and falls off when the economy is good.

MMTers sound a lot like Keynesians. If only we had stuck to this simple plan!

Can you comment on how borrow and spend affects the picture? The costs of some remedies are kicked down the road. When cause and effect are not measured in the same time frame, the resulting “data”” is not reliable. [e.g., productivity that takes output from one fiscal year, downsizes, then takes the “input” from the leaner year, gives a result of improved productivity.] Time is a component.

Creditors hate inflation (you noted why) and in this modern western economic “system”, creditors come first. Everyone else will suffer so that they can prosper. Welcome to “capitalism” or maybe it should be called “creditorism”.

Take this as opinion as I am no expert.

Doh, meant as a reply to VT Digger above

The fundamental issue is that the Central Banks are using a very widespread damaging policy of rising interest rates to reduce inflation.

All they can do is reduce aggregate demand by harming workers. Part of this seems to be a very deliberately staged attempt to damage what little bargaining power that workers have accumulated as a result of the pandemic. Certainly there’s an argument that was what Paul Volcker did in the 1980s, as the article hints.

The big issue is that the higher interest rates can’t magically create energy out of thin air or magically fix supply chains. It would require an industrial policy to address many of the ongoing supply chain issues. The energy issue – again it would require direct subsidies to energy companies or MMT and the money goes to state owned energy companies to expand capacity.

The private sector is not going to do it, so it has to be state owned. The private sector is buying back shares and not expanding capacity.

https://www.investors.com/news/oil-companies-target-buybacks-over-production-increases-as-prices-drop/

Also, keep in mind that the debt levels today are much higher than they were in the 1970s and 1980s. This could be a lot more harmful for society than raising rates was back then.

Ultimately, independent Central Banks are a bad idea. They just encourage a policy that props up rent seeking finance at the expense of the real economy.

Dean Baker frequently points out things Congress (not the Fed) could do, such as not letting pharma profit on government-funded research, and tackling patent law, to structurally reduce costs in the economy.

The Central Bank policies also created epic asset bubbles.

Here in the USA, for one example, it has to be admitted that the highs of stock portfolios were fantasy finance numbers.

25% drops from valuations that were hyped on lies should be thought of as a fall to a semblance of reality (but even that is being done with maximum manipulative effect). So many closed their eyes about the implications of that and fantasy finance prices for homes. All kinds of half-wit justifications were made and now people are worried about “fundamentals”?

The trap is that every time the interest rates are lowered, the money isn’t used productively. Frankly, it is used for gambling and increased monopolization. The lock on the trap is hold that the mavens of deregulation of finance have on the key.

It’s not only gambling and monopolization, there’s also scams. You think crypto currencies, NFTs etc are bad? I bet 10 more years of low interest rates will create all sorts of new Ponzi like schemes that boggle the mind. What happens if 20% of the economy is built on scams? How about 30%, 40%? What happens when that blows up? Growth will not be affected? Hard to believe. “The authorities will step in before that happens!!” Well that may be the case back in the days, but nowadays? Basically it’s not just the growth that matters, there’s also the quality of growth. If growth quality does not matter, then why are we criticizing the Chinese for building those ghost cities and infrastructure that’s barely used? Everything’s good right??

I never lived through the 1965-82, but it can’t be the case that nothing has changed.

1. The world is more globalized now. Yes there will be growth, but most of the growth will be found elsewhere. Jobs certainly will not be returning to the US. A lot of companies will borrow at low interest rates in the US and invest somewhere else, preferably in countries with lax environmental and labor standards. We’ve seen this movie before.

2. Way less financialization back then? Yes there were hedge funds, but the real vultures like private equity hadn’t showed up yet. With continued low interest rates, those guys can really do some serious damage!!!

3. Energy/population ratio was more favorable. There’s less energy now to go around for everyone.

I am sure there’s other differences since then that makes any comparison between now and 1965-82 somewhat weak. We live in an era where perhaps only stupid can fix stupid.

IMO hyperinflation is a balance of trade effect, involving a massive lack of export to balance off imports. And one that many a nation these days has been made susceptible too thanks to IMF “advice” to focus on cash crops over staple foods.

Anyways, central banks were created for two reasons. Originally to handle lending to kings, then later to handle bank runs.

Who wants to live in a world with 15% inflation? People on fixed incomes certainly don’t. People who save for rainy days certainly don’t. Central banks made huge mistakes with their money creation shenanigans and other manipulations. Central banks are the problem. Lets rid ourselves of them.

Who are these people who live on a fixed income? Anyone well enough off to not have to rely on social security (which is inflation adjusted) tends to own assets besides just 30 yr treasuries

Only well AFTER the damage is done, we might be somehow lucky if central bankers are put under the microscope and found guilty of monetary mismanagement. Problem is, we tend not to learn lessons lately.

IMO, neutral monetary policy means short term interest rates equal inflation.

But given how the inflation horse has left the barn post-Covid, crushing the US economy to bring inflation to 2-ish percent is unconscionable.

In an honest world, the Fed would admit that it failed (Biden and the EU as well w/their anti-Russian sanctions policy), and have the world live with US interest rates around 5% for the next 12-36 months.

Living w/5% inflation, negative real wage growth, and de facto full employment (even w/depressed labor participation rates) is the lesser of two evils—2% inflation at the cost of 6% unemployment.

For some historical perspective: Twice in 1980 and twice in 1981 under Volcker the fed funds rate hit an astronomical 20%. In that time and later, unemployment never exceeded 8%. In the grand scheme of things, the US economy and its participants survived without too much damage and recovered from the shock rather quickly.

Long term, the fed funds rate has averaged 5-6%. Today it is a puny 3% and yet everyone is predicting economic Armageddon if the Fed should raise it anymore. 5%? Gawd forbid, we’re all gonna die!

If the US economy can’t sustain normal interest rates, it is a sick, ailing economy, using debt like medicine to feel better and forget about the inevitable contraction that will come from 15 years of artificially low Fed rates.

In the early 80’s, the Communist Bloc party had pretty much neutered itself in terms of consumer exports.

I think Stolichnaya vodka was the only Soviet product on our shelves, and the Chinese were more concerned with when the next bowl of rice was coming, the only import of theirs of note being fireworks.

In that era an average home in LA was $100k @ those sort of interest rates you mentioned, so now it costs you 6.66% only, why the caterwauling, er, over the very same 50 to 60 year old house now worth a million clams.

The only bubble of that era got squashed by the powers that be, silver going from $6 an oz to $48 in 79-80 thanks to the brothers Hunt.

Everything and I mean everything is extra bubbly now, and past performance isn’t necessarily indicative of future performance.

Do you really think that US 1981 was so similar to 2022 for your simple extrapolations to be valid? For instance, is debt amount and structure similar now to that of 1981?

The biggest problem was letting debt servicing become so much of the GDP.

At some point it’s time to call it the trap that it is instead of perpetuating the problem.

To address your question directly, in 1980 the US national debt was $900B. Today it is over $30 Trillion. Can that in any way be construed as a positive?

Economics is complicated and my only “expertise” comes from investing experience and books I have read. Things change in forty years, I agree. But I also think that certain truths prevail. Among others, debt is bad, saving is good.

Is that simplistic view wrong in the current economic climate? It well could be. I am willing to admit that. Economics is complicated, as I said, and I am no dogmatist.

That being said however, one of the biggest mistakes that economists and investors make is that they believe “This time is different”. Consequently, they feel safe in throwing out the rulebook, even though history is replete with examples where the times turned out to be, regrettably, not different.

I will only cite “Tulipmania”, the “South Sea Bubble”, the “Roaring Twenties”, the “Nifty Fifty ” of the ’70s, and the “dot.coms” of the early 2000s as exemplars of this kind of thinking.

.

This is again simplistic. It is not just the amount of debt but its structure: who holds it how are holders exposed, where the income comes from, which assets back the debt and how these behave during the crisis. This is only to start with as there are many other considerations about relative strength of markets, wealth and income distribution, etc. Yet with this analysis, even if admitting not to be thorough, you reckon knowing the true rules without being dogmatic. Isn’t it? And, of course, the [family blog] with those idiots abroad with dollar denominated debt.

The national ‘debt’ is the amount of money in private hands.

Private debt is bad if it’s not for production. Saving is good, unless everyone does it.

‘Investors’ are maniacs. Central banks are the opposite, every problem is given the same old treatment which has never worked.

In and of itself, it can’t really be construed as anything. It’s not debt in any meaningful or even coherent sense of the word. It’s not owed to anyone.

Correct — it’s the private debt, not the sovereign debt, which causes systemic problems, as explained in Richard Vague’s “A Brief History of Doom.”

I’d suggest thinking of national debt as if it were bank debt. Your bank account is your asset, but the bank’s liability. Marching down to the bank and demanding it reduce its debt (i.e. make your account smaller) is far from sensible, but that’s what passes for “Fiscal Responsibility[tm]” now…

The history of inflation shows that wage increases are rarely the main driver, for two basic reasons:

1. Wage increases almost always lag inflation.

2. Wages are only a fraction of the inputs to production, counting investment/depreciation, materials, taxes, and (enormously in the last few years) distributed profits.

Some day, when the government again puts a thumb on the bargaining scale between powerless labor and monopsomistic business, wages will actually outpace and drive some inflation (reduced by a reduction in the bloated profit share). Is that a bad thing?

Inflation tends to redistribute upwards. I am at a loss to find evidence of any “wage-price spiral” in US history ever achieving the opposite, notwithstanding the ominous whispers of the phrase. 5% wage growth (after decades of stagnation) is a wage-price spiral??

I’ve been back and forth on the Fed’s idiocy and what they are doing with interest rates and my conclusions tend toward the following.

1) Interest Rates effect asset prices (stocks, housing, etc.) to a far greater extent than they do consumer goods prices (e.g. bread, milk, baby formula). This is because rates primarily effect borrowers (housing) and those looking for returns (stocks)

2) Rates have been too low for too long. While wall street wants booming housing and stock prices, main street would prefer slow, stable growth and the ability to earn interest income on savings.

3) As Warren Mosler has pointed out, the “natural” rate of interest is zero. Therefore, it is up to the fed to set the risk-free rate. We need a positive risk-free rate to encourage savings over risky investment, and to help those on fixed incomes. Personally I think somewhere in the 3-5% range is appealing, but you can debate the proper rate.

4) Interest rates have fuck-all impact on employment, unless the Fed decides to go nuclear. My industry currently has a large surplus of well paying white-collar positions that we just cannot fill. Not to mention all the $10-$15 an hour jobs that noone wants.

It has become clear to me that “independent central banks” are inherently aristocratic institutions hostile to labour — they are anti democratic by design.

Once you grasp this their behaviour becomes predictable.

1. No inflations ever have been caused by excessive government spending or by interest rates that are too low.

2. All inflations are caused by shortages of key goods and services, most often shortages of oil and food.

3. Today’s inflation began with COVID-induced shortages of oil, food, shipping, labor, computer chips, etc.

4. The only cure for inflation is to cure the shortages.

5. Raising interest rates does not cure shortages; it exacerbates shortages.

6. The primary effect and purpose of interest rate increases is to recess the economy.

7. Stagflation, here we come.

RMM,

The only point I will argue around is 6.

The primary effect and purpose of interest rate increases is to increase unemployment (supress/lower wage levels). Recessing the economy is an unavoidable side effect, but on balance, worth the cost to business – as when the economy picks up low wage levels persist, labour is [further] disempowered, thus enhancing long term profit levels post recovery.

Of course interest rates rises also have many positive spinoff benefits for financiers, investors/traders, bankers etc.

All in all business wins – that’s why central banks don’t mind being “forced” to pull that lever.

Myths 1 and 4 sound like Goebbels: “Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes the truth”