Yves here. In this second part of his series on the world implications for the end of the US empire, which it is managing to accelerate with its Russian sanctions blowback and military and economic eyepoking of China, Das uses the accelerating crisis in the UK as a case study. He argues that many of its elements apply to the US.

While Das is persuasive on the sorry condition of the UK, which has long been in a perilous state by being a small, open economy with an outsized banking system, I anticipate reader quibbles with this chapter in his series. Das does not appreciate that the financial system does not allocate savings (this is the loanable funds fallacy) but that banks create loans and deposits ex nihilo. But the conclusion is correct, that our modern financial system does a dreadful job of allocating capital to productive uses.

Das does describe some of the impediments of moving away from the dollar despite the keen desire of China, Russia, India, and the Global South to do so. Das also offers some quick thoughts. And he provides a nuanced and detailed discussion of decay in Western political and social structures, compared to conditions in China and Russia.

By Satyajit Das, a former financier whose latest books include A Banquet of Consequences – Reloaded (March 2021) and Fortune’s Fool: Australia’s Choices

Ordinary lives are lived out amidst global economic, social and political forces that they have no control over. Today, multiple far-reaching pressures are reshaping that setting. This three-part piece examines the re-arrangement. This first part examined current great geopolitical divisions. This second part looks at key vulnerabilities. The final third part, which will appear on Friday, October 28, will look at possible trajectories.

Economic weakness is usually central to social and political breakdowns. The ability to meet the population’s inexorable demand for goods and services is essential to stability. Today, there are fundamental financial vulnerabilities.

Economic Susceptibilities

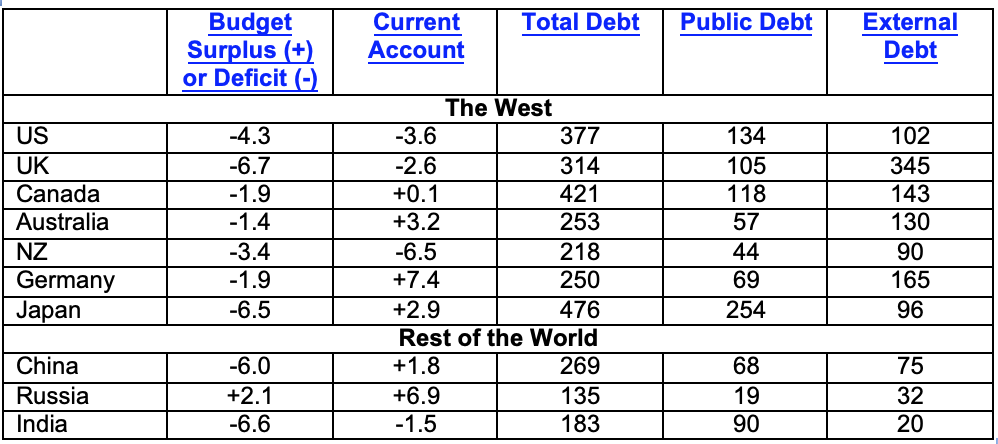

Application of standard metrics of resilience -internal (budget) and external (current account) deficits and debt levels, especially amounts owed externally- yields interesting results:

Notes:

- Budget Position, Current Account, Total and Public Debt (gross) are all stated as a percentage of GDP.

- Total debt is taken as all non-financial private and public debt. External Debt is recorded as total debt owed externally as percentage of GDP.

- All data is for 2021 or the most recent available.

While point-of-time data has its limitations, the West is running substantial twin deficits (budget and current account). Canada and Australia’s strong current account performance is driven by high commodity prices and volumes. These factors also underpin both nation’s government revenues and help keep budget deficits in check. Germany and Japan’s current account is vulnerable to falls in exports, such as to China, and elevated energy prices.

Western budget positions are precarious. Germany and the UK are spending €300 billion ($300 billion or 8.4 percent of GDP) and more than £100 billion ($110 billion, or 4.3 percent of GDP) respectively to protect households and businesses from higher energy costs largely funded by borrowings. The UK also proposed but later abandoned an ambitious fiscal program to boost growth with tax cuts totalling an additional 2 percent of GDP.

The West’s debt levels and external indebtedness are elevated. Weak public finances and excessive government borrowings can feed inflation and push up interest rates. It can weaken the currency which, in turn, drives price rises and further rate increases. The build-up of debt affects growth and limits the ability to respond to recurrent economic or financial crises, pandemics, climate change and wars.

China and India also exhibit deteriorating economic performance. However, high saving levels and the ability to finance without reliance on external sources is helpful. On all metrics, Russia’s position remains positive although its dependence on raw material exports remains untested, especially under prolonged harsh sanctions.

Kindness of Foreign Creditors

Higher interest rates, the shift from quantitative easing to tightening and restrictive monetary conditions will make it more difficult for the West to refinance maturing obligations or borrow to meet future needs. This may be affected by changing global capital flows.

Since the turn of the century, the West, especially the Anglosphere, has to varying degrees relied on German, Japanese, East Asian and Middle-Eastern savings for external funding. Outside of commodity producers, especially energy, these current account surpluses are now shrinking as a result of export slowdowns and higher energy costs.

Western actions against Russia– seizure of reserves, exclusion from the SWIFT payment system and international financial markets- are significant. US confiscation of Russian central bank reserves is difficult to distinguish from a selective currency default. It may undermine the willingness of surplus countries to hold reserves in US dollars and to a lesser extent Euros, Yen and Anglosphere currencies.

A related development is de-dollarization. In the post World War 2 period, the US dollar’s reserve currency status has provided America with what French Minister of Finance Valéry Giscard d’Estaing christened the “privilège exorbitant” . About half of international trade is invoiced in dollars, well above the US share of global trade of around 10-15 percent. In foreign exchange markets, dollars are involved in nearly 90 percent of all transactions. 60 percent of reserves are held in US dollars, the bulk in Treasury securities de facto financing the American government. This may be changing, albeit slowly.

China, Russia and the non-West have begun to settle trade in Roubles and Yuan through alternatives to SWIFT. Confiscation risk may reduce investment of reserves in dollars. Central banks and sovereign wealth funds may shift to other currencies or real assets to reduce exposure to confiscation. China has been moving away from US Treasuries for some time. It has cut US debt holdings by 9 percent to under $1 trillion from the end of 2021 to July 2022, a 12-year low and well below the all-time high of $1.3 trillion in Nov 2013. It has invested in its Bricks and Road Initiative, which has created different risks.

The switch away from dollars is difficult due to the lack of alternative liquid, large currency and money markets. Faith in non-Western currencies and their sovereign backing is not high. It will be resisted ferociously by the US which would risk losing economic and financial leverage.

But any shift away from the US dollar and Western currencies will make funding of ongoing deficits and refinancing external borrowings more challenging. Reliance on the kindness of foreign creditors is always a risky long-term strategy.

Domination Games

The dominance of the US dollar is under threat for other reasons. In 2022, higher interest rates pushed up the US currency to a 20-year high on a trade weighted basis. Dollar strength was only relative. Most currencies have lost actual purchasing power over recent decades significantly as a result of debasement and monetary excess over several decades. Portrayed as a flight to quality, it was, in reality, more akin to trying to find the least dirty shirt in a laundry basket on Monday morning.

For America, it reduced the competitiveness of exports, decreased translated overseas earnings and made dollar denominated investments expensive. However, the cost to the rest of the world was greater.

The strong dollar increased commodity prices which are mainly priced in US currency terms. The offsetting depreciation of other currencies imported inflation. For emerging markets with high levels of foreign currency debt, the combination of a strong dollar and higher interest rates was financially damaging. American firms could also buy up foreign businesses at bargain prices because of its soaring currency. A strong dollar historically tends to be contractionary for the world economy.

The ‘reverse currency war’, as it was labelled, forced countries globally to push up rates in increments up to 1 percent instead of normal smaller rises increasing the risk of a severe economic downturn and financial instability. Josep Borrell, the high representative of the European Union, publicly criticised the US central bank for its aggressive rates rises which would most likely affect the continent far worse than the US. The former head of India’s central bank Raghuram Rajan posed the obvious question: “If a poorer country over borrows in the good times because global interest rates are low, what responsibility does the US have for that?”

Western weaknesses reflect underlying toxic pathologies. The predominant consumption and debt driven growth model is waning. Unfavourable demographics, especially an aging population, and rising commodity prices act as retardants. Financialisation, a major driver of activity, is less effective with high debt levels, overvalued assets and higher costs of capital.

For decades, eschewing structural adjustment, Western policymakers have relied primarily on shock and awe monetary finance – government deficit spending, ever lower interest rates and injections of liquidity. Accommodating markets seemingly placed no limit on debt levels. It was grounded in the theory that “quantity has its own quality” (Stalin’s alleged reference to Russia’s World War 2 strategy of using large numbers of under-equipped and less-well-trained soldiers). Borrowed money came to be equated to earned income.

The lengthy experiment with ultra-low rates and QE (quantitative easing or central banks purchasing bonds to inject liquidity) reveals the excesses. The rapid growth in debt, both public and private, was only sustainable at low rates. By 2022, higher inflation, resulting from rapid growth in demand, substantial increases in money supply as well as Covid19 and conflict driven supply disruptions, necessitated a winding back of expansionary policies and increases in interest rates. The rise in borrowing costs affected the ability of borrowers to meet commitments.

There were subtler effects. The central bank policy of purchasing long-dated government and, in some cases, private debt financed by creating reserves worsened the sensitivity to higher short-term rates. According to the Bank of International Settlements, perhaps 30-50 percent of advanced economy government debt was converted to overnight borrowings in this way. This is now magnifying the effect of rate rises. It has also left central banks with large unrealised losses on its holdings of government bonds which combined with rising borrowing costs may ultimately have to be borne by the state and taxpayers.

Monetary mechanisms have been corrupted. The financial system no longer simply aggregates savings and allocates them to finance productive enterprises. Instead, governments and central banks use financial institutions to channel supplied liquidity to refinance existing debt, supported by overvalued real estate or financial assets, or provide additional credit to prop up consumption to create phantom growth.

Over the last three decades, ‘Botox economics’ and ‘extend-and-pretend’ was used repeatedly to cover up problems or defer unpopular decisions. In an extension of Gresham’s Law, bad policies and complicit leaders crowded out good ideas and necessary reforms. Denial and cognitive dissonance masqueraded as plans. Today, with options dwindling, Western policymakers resemble chess players faced with the realisation that the best available move is nevertheless bad and will lead to ultimate defeat – the German term for the predicament is zugzwang.

Similarities and Differences

Dysfunctional societies complicate the West’s position.

Ostensibly participative political systems are approaching anarchy. The value of suffrage has been reduced by routine gerrymandering, choices between unpalatable, incompetent and absurd candidates, lack of understanding of key issues, and the absence of substantive policies. The result is civic and electoral disengagement. Narcissistic leaders, unable to accept rejection, routinely claim fraud when defeated. Election denial, the new pandemic, further reduces trust in the process.

Governments mainly serve well-funded or vocal special interests. As Mancur Olson forecast in The Logic of Collective Action and The Rise and Decline of Nations well-funded coalitions now influence policies ensuring benefits to narrow interest groups leaving large costs to be borne by the rest of the population. Alternatively, JK Galbraith’s countervailing forces create paralysis. In truth, it is difficult and perhaps impossible to govern nations which are increasingly polarised (Presidential Trump received 47 percent of votes in his 2020 defeat).

The lack of consensus, complex challenges and lack of costless solutions is partially behind the culture wars of Western democracies. Worthy social causes -liberty, gender, sexuality, race, history, indigenous rights, multi-culturalism- are now central to delineating political differences. These power or hierarchy focused debates are difficult to resolve because they involve earnestly held beliefs and values. For politicians, they are priceless allowing them to project authenticity and manipulate a fissiparous electorate.

Leaders themselves are an uninspiring lot, long on cunning and media savvy but little else. Constant scrutiny of private lives and better financial rewards elsewhere mean politics attracts in the main uniquely unqualified aspirants whose highest potential is mediocrity. There is daily confirmation of Aesop’s observation that “We hang the petty thieves and appoint the great ones to public office”. Elected representatives, many unknown to voters, serve as Lenin’s parliamentary cretins rubber stamping the celebrity leader’s will or ensuring policy paralysis.

Politics is “panem et circenses” (bread and circuses) as Juvenal wrote in Satire X. Standard operating procedure is appeasement framed as glib announcements or a fashionable tweet which will largely remain unimplemented. The objective is to distract and divert while maintaining popular approval. Outside elections, it is the preserve of professional politicians, operatives and a breathless media providing low-cost, constant entertainment for political addicts.

There is parallel institutional decay. State bureaucracies, once capable of providing objective and independent advice, have been decapitated. Career specialist public servants have been replaced with malleable political appointees. Accreditation and domain knowledge, a fundamental requirement for most professions, does not apply now to public policy.

Law enforcement and the judiciary are increasingly politicised. Courts frequently operate as alternatives to or substitutes for legislatures. Police discrimination against minorities is routine. Justice requires deep pockets or ability to garner fickle public or press support and a popular podcast arguing your side of a case.

The traditional press, for the most part, now cannot distinguish between facts, analysis and opinion. Some have abandoned balance and impartiality becoming overt advocates. Others have evolved into semioticians, endlessly debating the accuracy of descriptors -fascism versus post-fascism- and correctness of pronouns for different sexual identities.

The cheap dissemination power of the Internet has seen the rise of highly variable independent bloggers (600 million at last count or around one for every 14 earth inhabitants) and websites (around 200 million active ones). A process of self-selection ensures that tribes congregate in cyber echo-chambers. Viral or trending items rather than factual accuracy or insight are the measure of success.

Western coverage of the Ukraine conflict was little more than Pravda-esque propaganda. Veteran correspondents, with field experience in covering conflicts, were struck by the one-sided and manipulative treatment of information and jingoism. It highlighted how verifiable facts necessary for an informed debate are no longer readily accessible to or even sought by most people. Ultimately, a world based on propaganda, manipulated factoids and conspiracy theories destroys trust without which institutions and authority cannot function.

Western societies, evolutionary biologist Peter Turchin argues, overproduce overeducated elites who expect high living standards and personal freedoms. They demand that governments shield their lifestyles, irrespective of practicality or cost, from the effects of economic downturns, extreme weather events, terrorism, influx of immigrants, disease or bad personal choices. They assume that bad things happen to others but not to them.

Today, limited employment options, stagnant incomes, the rising costs of middle-class life – housing, food, energy, health, education- and uncertainty mean that their expectations cannot be met. Shortages or rationing of food and energy would not sit well with a population for whom deprivation is a late online delivery, slow Internet download speeds or unavailable crudities of choice. It creates stresses reminiscent of the 1930s.

US founding father John Adams was correct in thinking that democracy wastes, exhausts and murders itself without the right conditions.

Differences and Similarities

These adverse trends extend beyond the West. Trade restrictions, sanctions, climate change and resource scarcity affect many nation’s ability to reach full potential. Deglobalisation is exactly the opposite of the traditional path favoured by low-income countries to improve living standards. Implementing import-substitution policies with the objective of going backwards and reversing technological modernisation is a novel development strategy. As the old saying goes: “you can’t get there from here.”

For the low- and middle income world, options are limited. The game of cheap raw materials and exploitation of a large, cheap workforce has largely run its course. Without access to the best global technologies, foreign investment, access to overseas markets and benign geopolitical conditions, further development is difficult. In addition, there are hangovers to be addressed. Real estate and infrastructure booms which relied on spectacular expansion in borrowing will leave behind bad debts and uneconomic or uncompleted developments. The primacy of political control, intriguing corrupt cliques, and ignorance of basic economics and finance means needed policy changes in most countries are unlikely.

Lack of progress creates a self-fulfilling cycle. Talent may leave, if not forcibly prevented, further limiting development. But the issues around technology and skill cut both ways. The West has benefitted from Russian, Chinese and Indian workers, highly trained in STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) oriented education systems. They have frequently contributed significantly to innovation and technological advances. This would be lost in a more fractured world.

Most non-Western countries save money and energy by dispensing with plebiscites or pay lip-service to democratic formulas. In some, there is no pretence at citizen participation, independent institutions, toleration of dissent or civil society. In others, lack of enforcement of elaborate and much-praised best-in-class legislation and regulations alongside falsified key-performance-indicators has the same end result. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban called this ideology – “illiberal democracy”.

The core concern is maintenance of power by individual leaders or the Party, irrespective of the means required. The existing machinery of the state, skilful adaptations of techniques of control and terror pioneered by past Imperial empires, is available to secure outcomes without heed to the cost. This is because the pressure for anything approaching full political enfranchisement is lower than in the West. Democracy means nothing to people who live for the most part in poverty without life’s basics. You can’t eat the right to vote although you might get a few cents for selling it.

These top down systems have advantages. Decisions can be made. Unpopular adjustments can be imposed. It is difficult to imagine China’s zero Covid policy being implemented elsewhere. However, the choices made by unchallengeable leaders who demand slavish obedience are far from infallible and sometimes unsound. The state’s enormous influence over the economy often engenders a lack of dynamism and encourages corruption.

In any economic or military conflict, the willingness of the population to accept losses and deprivation is an important but not sufficient condition of success. In World War 2, the Soviet Union lost around 27 million (including 11 million military personnel) of its citizens, including nearly 5 million just between June and December 1941. Over the entire campaign, Germany’s Eastern front losses were around 4 million, a fraction of their opponents equivalent to a favourable 3:1 kill ratio. Yet Operation Barbarossa failed and the war was lost. Autocracies are able and willing to inflict greater suffering on subjects than is possible under more democratic systems.

Outside the West, expectations are more limited. In a world of low living standards, the social contract entails different trade-offs within the Maslow hierarchy. Inequality, which is high in the non-West, can be an advantage as rulers can improve their popular standing by shifting the cost of adjustments onto the small group of the wealthy or privileged.

China’s crackdown on private businesses and corruption, frequently difficult to distinguish from Stalinist purges, enjoys support from many low-income citizens. The effect of Western sanctions on Russia have fallen disproportionately on wealthier, more cosmopolitan urban citizens and oligarchs. Being denied access to Apple-Pay, French cheese or your custom-built super-yacht are not major concerns to the vast majority of Russians.

Contradicting Western portrayals, both President Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin have enviable personal power and support of ordinary citizens for their attempts to improve the position of China and Russia. Their attempts to correct historical slights and throw off Western yokes is popular, outside an Anglicised urban minority.

The fall for the West will be further and therefore harder, heightening discontent which may manifest publicly. It can be highly organised and effective, such as France’s gilets jaunes (yellow vests) movement. Outside the West, any dissent can and will be suppressed quickly and brutally.

But the fracture between different parts of the world will mean reduced global co-operation and little advancement on critical issues – climate change, public health and refugees. Lack of contact and scholarly or people-to-people exchanges will confirm biases and encourage adversarial worldviews. Misunderstandings and mistakes will escalate increasing the risk of conflict.

Universal blindness, the likely outcome in an eye-for-an-eye world, benefits few.

© 2022 Satyajit Das All Rights Reserved

This piece draws on an earlier series published in the New Indian Express.

The depth and breadth of this is going to require some rumination. Thanks for posting it.

Maybe the truth of the matter is that we are all playing our part in a future book called “The Rise and Fall of the West.” We all of us grew up in a system that originated in a small peninsular that came to dominate the world. But nothing lasts forever and the idea that other systems from other regions are rising that will challenge the west has been a long time coming.

maybe our bettors should have paid more attention in the team building exercises…

I just don’t think that “because I f@(k$^& told you to, you moron” is in that curriculum, but I could be wrong…

The most useful statement in this entire post:

The West’s capital allocation mechanism is wrecked at the top, and we’re victims of their incompetence and malignancy.

We’ve ceded the vital capital allocation function to people that actively mean us harm, and demonstrate that fact every day, in every quarter.

How to respond?

We little people need to get good at allocating our capital to productive uses that actually, directly, benefit our households.

We should invest in ourselves, and get really good at doing it.

=====

At the moment, we are spending a great deal of time chronicling our systematic demise.

What should we be _doing_ now?

Efficiency isn’t a solution. In the case of better allocated capital, it’s only an efficiency change in the paradigm, not the paradigm itself. As far as I have bee able to see there is NO country/government/system that is NOT based on continued growth. Continued, perpetual, growth IS the paradigm. ALL will eventually hit the proverbial wall (the West is now seeing that wall for the first time). As I’ve long said, capitalism is able to produce the best noose, one that we use to hang ourselves.

What should be be doing now? Refer to: And The Band Played On (of the Titanic story)… (I’m not suicidal, in which case I suppose I’ll be around to find out and feel how ugly it all will be. May mercy be upon us…)

agreed, Tom. “Investing in ourselves” means mindfulness in how we spend our time and our treasure with’s view toward long term sustainability. When we buy junk that will see a landfill all too soon, made in some developing country by explored labor sold by a corporation that has no interest except cost reductions and short term profit maximizations, we serve the master who enslaves us.

We vote daily with our time and attention and spending.

Sadly, so many of us have become dependent on the flow of this that we won’t as we risk harming our own cash flow and short term financial prospects. We also have our worth tied to what we “own;” even if it, in fact, owns us. I don’t have an answer for that except to suggest considering the short term vs long term impacts. We may “win” today yet by so doing become enslaved tomorrow. It’s worth thinking longer term, I believe.

So beyond that, perhaps endeavoring for more self-sufficiency and focusing time and resources on that, so when the proverbial shit-hits-the-fan we won’t be as starved or decimated. Resilience doesn’t happen by accident.

We can also make clear that we will not participate in any future wars which are certainly avoidable.

We can be happy with less. We can only buy what we truly need. We can make sure what we do buy is built to last and can be repaired, even when it costs more up front.

We can grow more of our own food, which improves quality and nutritional value and also prepares us for when we may need to supplement our diets when what is available isn’t sufficient.

We can put more of our cash into bullion or productive assets and self-warehoused crypto, depending on your risk tolerance.

We can focus on improving or maintaining our health, reducing reliance on pharmaceuticals for mind or body. Stronger and more resilient bodies will weather any likely disturbances better.

All these things begin to steal from the source of the dysfunction described so well in this article. Perhaps contributing to build awareness so one can have an understanding of how it just so happens that the description provided can apply to most any Western country today. Where does this rot stem from? How did it become so commonplace for all our governments to fail so miserably at providing for and creating the conditions for most humans to thrive. Who benefits? Who pays? Why are so many measures of well-being going backwards instead of improving? How did the few become so powerful as to benefit while the many work harder and have less to show for it? Having answers to these questions will make it easier to decide what deserves one’s attention and support.

I would also add that supporting any activism or reforms that increase transparency and make public and publicly accessible the data required to make sense of our world. We suffer from backroom deals and hidden data, and because of that it is easier to feed us lies, so we make poor decisions.

Beyond that, watch for the tipping point. It usually seems to come when enough have been injured or fear being injured by the status quo. The risk of staying the same becomes greater than the risk of change. What doesn’t work has become more clear!

Societal Illusions:

That is one of the _best_ renditions I have seen on “what to do”. I could add some stuff, but yours is so good, I think we should just enjoy it as-is.

One of the very helpful aspects of your post is that in addition to being quite specific in spots, it allows a great deal of latitude about how the individual expresses themselves.

We are all starting @ different places, with different resources and “mindfulness”.

If we help ourselves (work as a team, somehow) to get ___( some unknown number)___ people to somewhat adopt that set of principles…it would work.

That tipping point would happen. Just like the transition from uni- to multi-polar.

“We vote daily with our time and attention and spending”.

Indeed we do. Somehow we’ve got this notion of powerlessness contaminating our mind-set. We have power: time, money, effort. We could get way better at using our power.

Your solutions seem rooted in individual actions. The problems we face require stronger collective leadership and decisions. As Garett Hardin (“Tragedy of the Commons”) said back in the ’60’s, solving the most intractable problems today require “mutual coercion mutually agreed upon”, i.e. laws. Hardin would also say, to reinforce this position, that individual virtuous actions (e.g. drive less to pollute less) amount to a “conscience penalty” that just confers a free benefit to those without a conscience, while ultimately accomplishing little. Only uniform “mutual coercion” in the form of, say, fossil fuel “tax and dividend” to deal with climate change, are apt to be both fair and effective. Hardin’s position is basically the way out of “prisoner’s dilemma.”

Yeah, right. That will really help. /s

amount to a “conscience penalty” that just confers a free benefit to those without a conscience

insightful

Karl said: “Your solutions seem rooted in individual actions.”

Exactly. My solutions are designed to occur where it’s possible for them to occur.

Your solutions seem rooted in a major top-down change. Top is owned by people that adamantly refuse to change, and have the power to keep it that way. Hence the “security state”, e.g. euphemism for “maintenance of existing socio-political order”.

Which theater of action is going to have more impact sooner, pray?

When is your revolution scheduled for?

Using less is an advantage, not a disadvantage. If you use less on x, you can use more on y if needed. It’s about prioritizing – skimp on your wants, so you’ll afford your needs. Ie, flying on a vacation vs heating your home this winter?

Hi Tom (posted earlier, so my apologies if this appears more than once),

I think we have but one realistic option: plan for the inevitable, become as locally self-sufficient as possible. I don’t mean hoarding, I mean sharing. I mean working to strengthen both the resources, the capital, under your control as well as local community resources so that you can help others: people in need, other families, children, elderly folks (or at least folks older than you), people who are disabled or handicapped in some way. Americans can be enormously resourceful: we need to ignite this capacity to conserve and preserve, to re-invent, to help, to educate, and protect one another, to reuse, to make do with less of everything – because less-of-everything is clearly where we are headed.

Additionally, engage in vigorous, loud, and public protest as our political “leaders” inevitably lead the US into yet another Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, hot war, cold war: They know how to do little else. In the 60’s, people (mostly young) were able to force the US out of Vietnam by relentless protest over a decade. It worked. It could work again. But where we are now is different.

Although most in the US must sense that things are not going well, they are also enormously influenced by the media’s relentless propaganda machine. For many, the idea that the US is truly failing as a nation is a very hard notion to accept – which is why it’s important that they understand what is happening. Today, I think our one chance at meaningful change is by unifying people — we, the little people — refusing polarization, forming alliances with those who are otherwise political opposites; it is that polarization which our corrupted political system relies on. But neither of those poles, neoliberalism versus identity politics, is sustainable. Both offer a false sense of autonomy of self, advertising a freedom to “do whatever it is I want to do” detached from personal responsibility, without recognition of our dependence on, and need to provide benefit to, each other. Neoliberal policies use wealth as power over others, and identity politics refuses to realize that who one thinks one is, is nowhere as set in stone as one imagines — and that humans were successful not because of any fixed identity of self, but in spite of it. We endured via cooperation, flexibility, communication, and political imagination: the capacity to imagine a better life for one another.

Keep it going, Rolf.

I hope you’ll continue to develop the theme of collaboration. I think that’s our current weak-spot.

I agree totally. We are individually small; in groups, quite potent.

I am looking forward to additional discussion about how to transit from isolated to unified.

Important point indeed, but it is a critique of financial capitalism. Meaning that the present system started to run after its own tail, so to say. Coming up with all kinds of financial instruments and starting to invest in those rather than in concrete industries. And increasingly so. And when it invested in a business, it started to trim the business – not for long future or sustainability – but to be sold as soon as possible.

Yes, it’s a critique of financial capitalism, but it’s not necessarily a criticism of industrial capitalism. I think Michael Hudson has made that case well.

My instinct is to move the industrial capitalism out of the realm of capital-concentrated, high-intensity production and disperse it as low-intensity local production processes, owned by locals, and operated in the interests of little people. Little people own the production process. They designed it, innovated it, built it, own it, operate it.

There are many high-intensity, highly capital-concentrated functions, like ag, energy, education, health-care, materials which may well operate more efficiently at the local level than they can at the high-capital centralized model we currently have. Those local models can certainly substitute labor for capital.

The existing production systems have morphed from efficient production processes to a collection of rent-extraction points, which simultaneously marginalize labor, and jack up prices (extract rents). The little people get whacked both ways. To wit: inflation is currently being exacerbated by opportunistic price hikes.

We have a surplus of underpaid, under-utilized labor. We know this because of the prices paid for labor (not a living wage), and because of the lower participation rates we’re seeing.

Evolve that labor into micro-scale industrial capitalists.

How? Good question. We’ll get to that next.

This second post in Satyajit Das series, like the first post, lacks coherence. It presents analysis by pastiche, loosely organized under headings. I am not sure I agree or disagree with any particular bullet points in the post. Regardless of this I am not at all sure what case those bullet points make in their aggregate.

BRI means Belt and Road Initiative, not Bricks and Road.

I have to say that I agree with a lot of the statements, especially “panem and circenses”, but I would love to see a little more incisive analysis. Maybe that is part 3.

My question is: where can you go as a Westerner if you do not agree with all this?

i quite reading it right here,

“Deglobalisation is exactly the opposite of the traditional path favoured by low-income countries to improve living standards. ”

there is a famous south korean economist that has debunked that slop. and america became rich under protectionism,

the west grew rich under protectionism and government policies that helped to redistribute the wealth.

Ben Franklin: the high wage protectionist constitution: The Doctrine of High Wages – How America Was Built: Proponents of the Doctrine of High Wages argued that not only were American workers better paid than their counterparts in England and Europe, but they were far more productive as well. In fact, American economists argued that high wages created a virtuous circle: the superior productivity of American workers allowed them to be paid much higher wages than anywhere else in the world, while those high wages provided American workers a much higher standard living, which, in turn, enabled them to be more productive.

” lincoln knew this well, tariffs are the easiest tax to collect. its why corrupt free traders hate them so much. its why europe has a VAT tax that punishes labor, and rewards corporations.”

https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2016/4/1/1508946/-HAWB-1800s-The-Doctrine-of-High-Wages-How-America-Was-Built

HAWB 1800s – The Doctrine of High Wages – How America Was Built

the author from yesterdays part one seemed to be very blase’ about supply chain disruptions, like he was surprised that counting on a few countries to feed the world, instead under Gatt large portions of the world were self sufficient in food.

and that making drugs and almost everything else 8000 miles away somehow became a unstable policy, like who’da ever thunk!

he seems to be saying back handedly, we need more free trade.

Michael Pettis has a very different take on the concept of “exorbitant privilege”. It seems that the country with the reserve currency status has to run persistent large current account deficit (with associated side effects including increasing loss of jobs and surging debt) to fund the global economic and financial activities. As long as China is focused on getting more trade surplus, CNY will never be a reserve currency, since there would be no circulating CNY in the global market.

https://carnegieendowment.org/chinafinancialmarkets/56856

in the Table what are the units.

eg Total Debt for US is 377. Is it billions, which does not jive with the oft quoted 30 Trillion of debt

An outstanding article which this financial ignoramus will peruse as a kind of study guide in macro economics.

One minor correction though: the term ‘Zugzwang’ (Zug = move, Zwang = obligation) just describes a situation in which one has to reactively execute a certain move. It lives entirely on the tactical level and doesnt directly infer a loss of the game. Almost all games show many of these situations on both sides as every player tries to impose this predicament on its adversary. Quantitatively they obviously reflect the dynamics of control on the board but cannot predict the very last Zugzwang situation which then, and only then, is experienced by the loser.