By Lucian Cernat, the Head of Global Regulatory Cooperation and International Procurement Negotiations in DG TRADE. Until 2020, he was the Chief Trade Economist of the European Commission. Originally published at VoxEU.

Numerous analysts have suggested that globalisation has permanently slowed or reversed, while others argue that it has merely changed in nature. This column argues that globalisation is a complex phenomenon that needs to be assessed with detailed, firm-level indicators that go beyond simple aggregate metrics. When using such indicators, the picture is much more nuanced. In the case of Europe, the role of global trade is as important as ever for hundreds of thousands of companies and millions of jobs supported by global trade flows.

Globalisation is a complicated phenomenon that is often oversimplified. The common conception is that the world has entered a period of reduced trade activity as countries have closed themselves off to trading with other markets. One of the key indicators referred to as evidence of ‘de-globalisation’ – or ‘slowbalisation’ – is the declining share of trade in global GDP.

However, Baldwin (2022) concludes that the reports about the death of globalisation are greatly exaggerated. He argues convincingly that globalisation is a complex trade phenomenon that cannot be captured with one simple macroeconomic indicator. For instance, it is enough to plot the evolution of this simple metric of globalisation for each of the top trading partners (e.g. the EU, US, China, Japan) and the de-globalisation story becomes more nuanced. The evolution of trade over GDP looks rather different for the EU compared to the other major trading nations, indicating that perhaps globalisation has not really peaked for Europe.

Three important conclusions come out of these analyses. First, as Baldwin (2022) clearly shows, the EU trade-over-GDP metric of globalisation has not really peaked. Second, to have a correct understanding of recent developments, one needs to use more disaggregated trade metrics than simple trade-over-GDP ratios. Third, globalisation is a multi-dimensional process and has to be measured across a wider range of economic indicators.

A better way to measure globalisation: ‘Trade policy 2.0’ firm-level indicators

In a new paper (Cernat 2022), I argue that a more precise way to measure the extent to which globalisation is shaping trade and economic relations is to rely on more disaggregated indicators, ideally firm-level trade indicators. As nowadays generally accepted in economics, nations do not trade; firms do. 1 Having a good grasp of trade policy realities would consequently also require such good firm-level trade indicators, leading to a ‘Trade Policy 2.0’ approach (Cernat 2014).

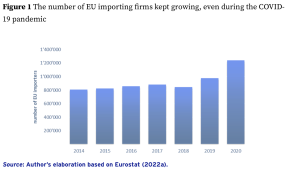

One detailed indicator that can capture the extent to which the EU has become more integrated into the global economy is the number of firms in Europe that engage in trade, notably the number of EU firms that rely on global supply chains and imported intermediates for their economic activities. As can be seen in Figure 1, the number of EU importing firms is growing, surpassing the symbolic milestone of a million firms in 2019 and reaching a new record of more than 1.2 million firms in 2020.

This finding is remarkable, considering the unprecedented shocks that global supply chains suffered in recent years and the massive decline in trade witnessed globally as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and other trade shocks. This growth in the number of EU firms engaged in trade is in line with other in-depth firm-level analyses confirming that a large share of global trade decline took place via a decrease in trade values or product varieties and not so much via a reduction in the number of firms engaged in international trade (see Bricongne et al. 2022 for a firm-level analysis of French exporters and Behrens et al. 2013 for an in-depth analysis based on Belgian firm-level trade data).

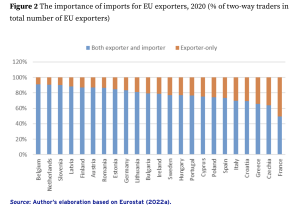

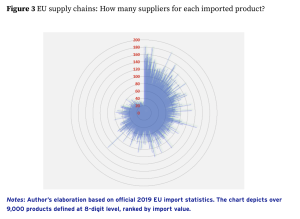

Another way to measure globalisation is to look at the extent to which ‘Global Europe’ requires well-functioning, diversified supply chains. Two detailed indicators can shed light on this aspect. The first one captures the importance of imports for EU exporters. As seen in Figure 2, for the vast majority of EU member states, more than 70% of exporters are also importers. A second detailed indicator to gauge the complexity and the diversity of global sourcing patterns for EU trade is to look at the number of suppliers for each imported product in the EU, at very disaggregated product levels.

Zooming in on one of the most disaggregated product levels of EU imports (8-digit product codes) shows us the staggering complexity and diversity of EU supply chains. Many of the over 9,000 individual products imported to the EU come from over 100 non-EU countries. The average number of foreign suppliers for EU imports across the full range of imported products is 68 countries. For the vast majority of products, the diversity of EU import sources at the firm level is even greater, since each country usually has more than one individual exporting firm for each of these products.

When trade means jobs: Has globalisation peaked for Europe?

Global trade flows are not just important for the 1.2 million EU importing firms; they are also a major source of economic activity for EU exporters. Participation in global supply chains has a positive and growing effect on jobs and wages in Europe. In 2000, extra-EU exports supported almost 22 million EU jobs (12% of total EU employment). By 2019, EU jobs supported by trade reached 38 million: 1 out of 5 jobs in Europe are supported by trade (Kutlina-Dimitrova and Rueda-Cantuche 2021). Many of the trade-supported jobs in Europe are found in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that are successfully engaged in global value chains: over 13 million jobs in Europe depend on SME exports (Cernat et al. 2020).

Services also have growing importance not only in global trade but also in the number of jobs supported by trade flows. When accounting for both direct services exports under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) and the ‘embedded services’ exported as part of goods (mode 5 services), services jobs represent nowadays more than half of total trade-supported jobs in Europe (Kutlina-Dimitrova and Rueda-Cantuche 2021). So, globalisation has not really peaked in terms of EU employment either.

The future of globalisation: Some open-ended questions

We have clear signs that globalisation continues on an upward trend in Europe, and one can only hope that past indicators of globalisation are a good indication for the future. However, globalisation is shaped by many powerful and unpredictable forces. There is a possibility that globalisation peaks in the future.

Some forces will work against globalisation; others will keep pushing towards more global economic integration. Take for instance the consumers’ love of variety. If globalisation satisfies this human need for greater (including imported) varieties, trade in consumer goods will not fade away. One good indication perhaps is the rapid increase in global e-commerce. In 2010, only around 4% of EU consumers engaged in online purchases from non-EU sellers. In 2021, 12% of EU consumers did so, buying a wide range of products online from non-EU sellers (Eurostat 2022b).

New technologies may lead to reshoring and automation that reduce trade flows (Seric and Winkler 2020), but they may also increase trade flows in unexpected ways (Mulabdic and Ruta 2019). New technologies such as artificial intelligence, 3D printing, the Internet of Things, and robotics will offer new trading opportunities for manufacturing-process and digital (mode 5) services built into ‘smart’ products. Digital technologies will continue to eat into the share of manufactured goods (from cars to fridges and pacemakers), and companies engaged in such activities will remain global players.

Apple, for instance, uses more than 170 direct suppliers (located in 30 different countries worldwide) for the parts and components used in their products. Now consider the number of services suppliers that are part of the Apple iOS App Store. In 2017, there were almost 500,000 active mobile app developers registered with Apple and over 700,000 app developers registered on Google Play (Ceci 2022). Like hardware suppliers, software and app developers are also scattered around the world, such as in Brazil, China, India, Japan, Romania, Ukraine, and the US. Our lifestyles will continue to rely on digital trade flows and software applications have virtually no physical limitations, except perhaps the memory of our smartphones.

All in all, there are many reasons to remain cautiously optimistic. While the future remains hard to predict, especially for major societal trends, it is fair to assume that humanity will keep some of its fundamental traits. If the future is hard to predict, our past is not. Archaeological evidence indicates that from the early days of humanity, trade played a critical role in ensuring the wellbeing of societies. As The Economist put it, “free trade and division of labour might be responsible for the very existence of humanity” (The Economist 2005). One may therefore say that Homo sapiens was born Homo mercatus. This helps put things into the longer-term perspective: whether we trade more or less in the short term, or any given year, becomes less relevant. What really matters for the longer-term prospects of globalisation is that trade is part of our DNA.

The West is trying as hard as it can now to fracture the global supply chains into two blocks, with BRICS as a separate entity that is to be challenged, not incorporated. As long as this trend continues, which is coming wholly from the US and parts of the EU, globalization will be dichotomized. How that plays out in the long run is anyone’s guess, because we just don’t know how that friction will play out, and how supply chains will sort out. We also don’t know if it will last, as the EU has good reasons for not wanting to go this route.

“Archaeological evidence indicates that from the early days of humanity, trade played a critical role in ensuring the wellbeing of societies. As The Economist put it, “free trade and division of labour might be responsible for the very existence of humanity” (The Economist 2005). One may therefore say that Homo sapiens was born Homo mercatus. This helps put things into the longer-term perspective: whether we trade more or less in the short term, or any given year, becomes less relevant. What really matters for the longer-term prospects of globalisation is that trade is part of our DNA” WRONG! Archeological evidence shows that for the first 40,000 years of its existence humanity lived long and happy lives in small hunter gatherer bands. Then, the climate changed and human beings moved to the mouths of rivers where resources were plentiful. With sedentism came tribal societies, then “civilizations” which ineeed depended on trade and division of labour. But division of labor meant social hierarchy and concepts of property — and (of course) slavery and war. . Nope. Trade is NOT part of our DNA.

https://www.amazon.com/Ageing-Young-Youre-Never-Rock-ebook/dp/B08T9G1YB4/ref=sr_1_2?keywords=ageing+young&qid=1636884520&sr=8-2

I’m experiencing a bout of cognitive dissonance.

One competing theme is “deindustrialization of EU”. The other is “trade increases because of our DNA”

If EU trade is to increase, EU needs to be able to produce things others want. How can that continue to happen in an environment of de-industrialization caused by input starvation (like energy)?

The trade numbers and trends presented in the graphs above suggest a high degree of import-export integration in “supply chains”, and they cite recent data. What will that data look like next year?

What would be especially helpful would be some current data on order books and purchasing-manager sentiment. I wonder if that would paint a more accurate picture of what trade flows might be in a year or two. I don’t know where to obtain that data in the EU context, or I’d link to it. Anyone know where to look?

In the M. Hudson interview, adjacent thread, there’s an assertion that debt, at all levels, continues to grow, implying that consumption is ahead of wealth-creation all across the West.

My point: you can continue to import and operate a (basically) value-add via distribution (not creation) economy so long as something (but not organic wealth-creation) is fueling demand.

That “something” seems to consist of new debt and, until recently, money supply expansion.

Here’s another slant on the topic. What do the EU importer/exporter supply-chain _value-add_ components consist of? Are those value-add components marketing functions (re-packaging, promotion, distribution) or create-functions, like integration/assembly, manufacturing, product design, etc.). That would tell an even more compelling story.

I’d also like to understand better what the major EU banks’ loan portfolio consists of. What functions and companies are those loans financing? What are the revenue / cash flows pledged against those loans?

The EU banks, at least some of them, have been struggling for years now, and it seems to be getting worse, not better. I think the pledged revenue streams are problematic, and that _may_ shed light on the rush to join financial / economic sanctions regimes .vs. Russia.

That last para is rank speculation on my part, but a look at the banks’ loan portfolio and the supporting income streams would tell a most eloquent story.

The benefits of trade outlined in the final paragraph certainly don’t require full globalization to be achieved in the main — competing trade blocs of considerable size in a multipolar world will also suffice.

EG, I agree. Seems to me we’re clearly headed in that direction – “competing trade blocs of considerable size”.

For me, there are two big unknowns:

a. Trading what? What are the trade flows, not just between blocs, but between companies that compose those blocs? What’s the distribution of “competitive advantage” and how are functions (value-adds) distributed across blocs? If these flows aren’t balanced, then either trade withers, or somebody’s debt balloons. Sort of what we have now, only more intensive, and a smaller pool to operate in.

b. What are the traits of the production processes are being used? How much wealth is being created, and how’s that wealth distributed? Corollary: where’s the demand coming from? Is the demand broad-based (deep and wide) or narrow and small, like a 1%-based demand? Is the demand fueled by debt / unbalanced money-supply expansion, or is it fueled by wealth creation?

When people talk about “re-industrializing the U.S”, they seem to leave out the question of “where’s demand coming from, going forward?”.

I also don’t see a lot of discussion about labor participation in the new re-shored production. When those production processes return to the U.S., will be they be the same, or more labor-efficient than they currently are, wherever they happen to be (EU, China, Taiwan, etc.)

“However, Baldwin (2022) concludes that the reports about the death of globalisation are greatly exaggerated. He argues convincingly that globalisation is a complex trade phenomenon that cannot be captured with one simple macroeconomic indicator.”

Yes, the death is greatly exaggerated. But I would say “globalisation is a complex FINANCE phenomenon…”

Or something like that.

Last time we tried ‘competing trade blocs of considerable size’ we got World War II. I don’t think we can do better this time around, but, given our technological advances, we can certainly do worse. Considering the breakneck speed with which American elites are galloping towards Doomsday, the oligarchs must be very busy right now adding the last finishing touches to their luxury bunkers.

I’ve just read that Vivos builds entire underground villages for billionaires and their minions, with swimming pools, hydroponic gardens, chapel, and health clinic. To borrow Trump’s go-to phrase, ‘It’s going to be beautiful!’ One builder of designer shelters had to add stables, because the owner cannot be expected to give up his race horses in times of nuclear winter. I would bet my retirement pension that the helpful idiots pushing a ‘limited nuclear war’ with Russia own spots for their families in beautiful bunker communities.

My concern is that I’m only 60 and I don’t think I’ll expire soon enough – before the ‘competing trade blocs of considerable size’ become Orwell’s Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia.

“As The Economist put it, “free trade and division of labour might be responsible for the very existence of humanity” (The Economist 2005). One may therefore say that Homo sapiens was born Homo mercatus”

Ignores entirely the work of Graeber who de-bunked the “homo economicus” myth years ago.

“What really matters for the longer-term prospects of globalisation is that trade is part of our DNA.”

As Tom mentions in his comment above, one experiences cognitive dissonance. There’s ‘trade’ and there’s ‘globalization.’ They are not the same.

Oranges shipped from California to Maine while Maine ships lobsters to Iowa: that’s trade.

Moving all the shoe factories from Biddeford to China, because owners can hire the Chinese for pennies per day. Because they’re benighted peasants. And the brick mills in Biddeford fall into ruin. Until taken over by the local Arts Council. And hundreds of shoe factory workers experience the degradation of losing their paychecks and trying to exist on unemployment. And the local businesses, the hardware store, the pharmacy, the diner, close because no one has the money to buy stuff. That’s globalization.

Right. Moving fish farming to Argentina where environmental regulations are lax and the toxic byproducts of aquaculture can just be dumped into a local river is another example.

Globalization is down but not out. I will believe it is dead when I walk into the grocery store, and I can buy oranges from Florida and the farm-raised fish from Argentina is gone.

Well said. The globalists always want free trade but never one global currency to trade with. That would take away the whole point of globalization, because without currency and labor arbitrage, it’s a lot harder to pauperize millions of people all at once.

Not convincing.

Amazon and apple, along with many others, are provably horrible employers…

global trade is as important as ever for hundreds of thousands of companies and millions of jobs supported by global trade flows.

Ever and always I will be suspicious of a per cent compared with a 1 in so and so…

In 2000, extra-EU exports supported almost 22 million EU jobs (12% of total EU employment). By 2019, EU jobs supported by trade reached 38 million: 1 out of 5 jobs in Europe are supported by trade I do agree that going from 12% to 20% in a 19 year span doesn’t sound that great…

New technologies such as artificial intelligence, 3D printing, the Internet of Things, and robotics will offer new trading opportunities for manufacturing-process and digital (mode 5) services built into ‘smart’ products. Digital technologies will continue to eat into the share of manufactured goods (from cars to fridges and pacemakers), and companies engaged in such activities will remain global players

Um, ok, whatever…vapid cheerleading bordering on “there is no alternative”

Archaeological evidence indicates that from the early days of humanity, trade played a critical role in ensuring the wellbeing of societies. As The Economist put it, “free trade and division of labour might be responsible for the very existence of humanity” (The Economist 2005).

Yeah, from 2005…what happened a couple of years after that? I mean, no one even says free trade anymore and I can’t wait til “smart” gets tossed in the same dust bin.

…and then there are this all too common projection…

Take for instance the consumers’ love of variety.

That’s why I shop almost exclusively at thrift stores, variety and generally much higher quality products…

again, globalization has been around since the 1500,s. what we are experiencing today is free trade.

that is trade that has been de-linked from democratic control, with the rules written by the rich, who are looking for any S##T hole they can find that has little or no civil society, and is willing to use their labor and their environment under horrendous conditions, that is why there is so much cross border supply chains.

the author like many fanatics completely over looks the horrendous damage that free trade has done to the worlds population and environment.

the incredible damage to the environment, the incredible debts and damaged humans created by free trade maybe irreversible for decades, if not for centuries.

we had lots of trade under GATT, that trade was more beneficial to the many, under free trade almost all GDP goes to a few. in the west, GDP is really a worthless number.

hardly anything to get excited about. the author seems to be the excited type.

JR McNeill (William H’s son) wrote a book with his father about the history of globalization, “The Human Web” which is pretty good

And James Goldsmith, despite being rather a rogue, wrote a great little book about the dangers of “free trade” (which ain’t free) in “The Trap”

One of the comments above mentioned Vivos, a company that makes shelters in which to live if the earth’s surface becomes uninhabitable from global warming and/or nuclear war. The wealthy have a viable plan.

Check out this link to Vivos, Watch the videos. https://www.terravivos.com/

Climate change, nuclear war, don’t worry about that stuff. NO PROBLEM!

I repeat. Quinn Slobodian has written Globalisation a somewhat difficult book that seems to explain globalisation as a simple consequence of neoliberalism.

He gives a good definition of the latter term. It is simply the process of uniting political theory and economic theory into a uniform theory. The economics is good old fashion liberalism while the politics is the codification into law of the ideas that laws should support liberalism and do so in a way to make laws protcting property and capital movement universal, i.e., independent of poltical boundaries.

To understand the latter, read Katharina Pistora’s book The Code of Capital.

Behind on my reading of NC.

Excellent points made in comments. I would add: what is being imported? Is there a domestic substitute which is dearer / no substitute (genuine comparative advantage) or has the domestic producer just folded because of high energy costs and so no alternative to imports? The stats surely only tell half the story.