Yves here. Yours truly has always strongly preferred living in densely populated areas. Running errands on foot was a way to get some activity in as well as a bit of a mental health break via checking in on the state of street life.

But as I have become older and creakier, I cringe a bit at the emphasis on walkability. What happens to those who can’t get around as easily? While no solution is perfect, taking this design priority at face value means that the mobility-limited are expected to cope….or live elsewhere. And mind you, “mobility limited” is not just the handicapped. All sorts of normally robust people sprain ankles, wrench knees, need foot operations, and so on. When you are limited to crutches, or worse, all of those formerly nothingburger distances like going across a cavernous lobby suddenly become daunting.

Note also that this article emphasizes energy savings via reducing driving. But apartment complexes are also more energy efficient by virtue of a much better surface to mass ratio, as in fewer exposed walls. My old apartment building in New York City had impressive thermal inertia. It took a full day for a change in outside temperatures to register inside.

By Sarah Wessler. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

Transportation is the largest source of greenhouse gases in the United States, and passenger vehicles — the cars most Americans rely on to meet their daily needs — account for more than half of transportation emissions.

Conversations about reducing these emissions typically focus on electric vehicles. But increasingly, government officials across the country are aiming not just to get Americans into different kinds of cars, but to radically reduce the need to drive in the first place.

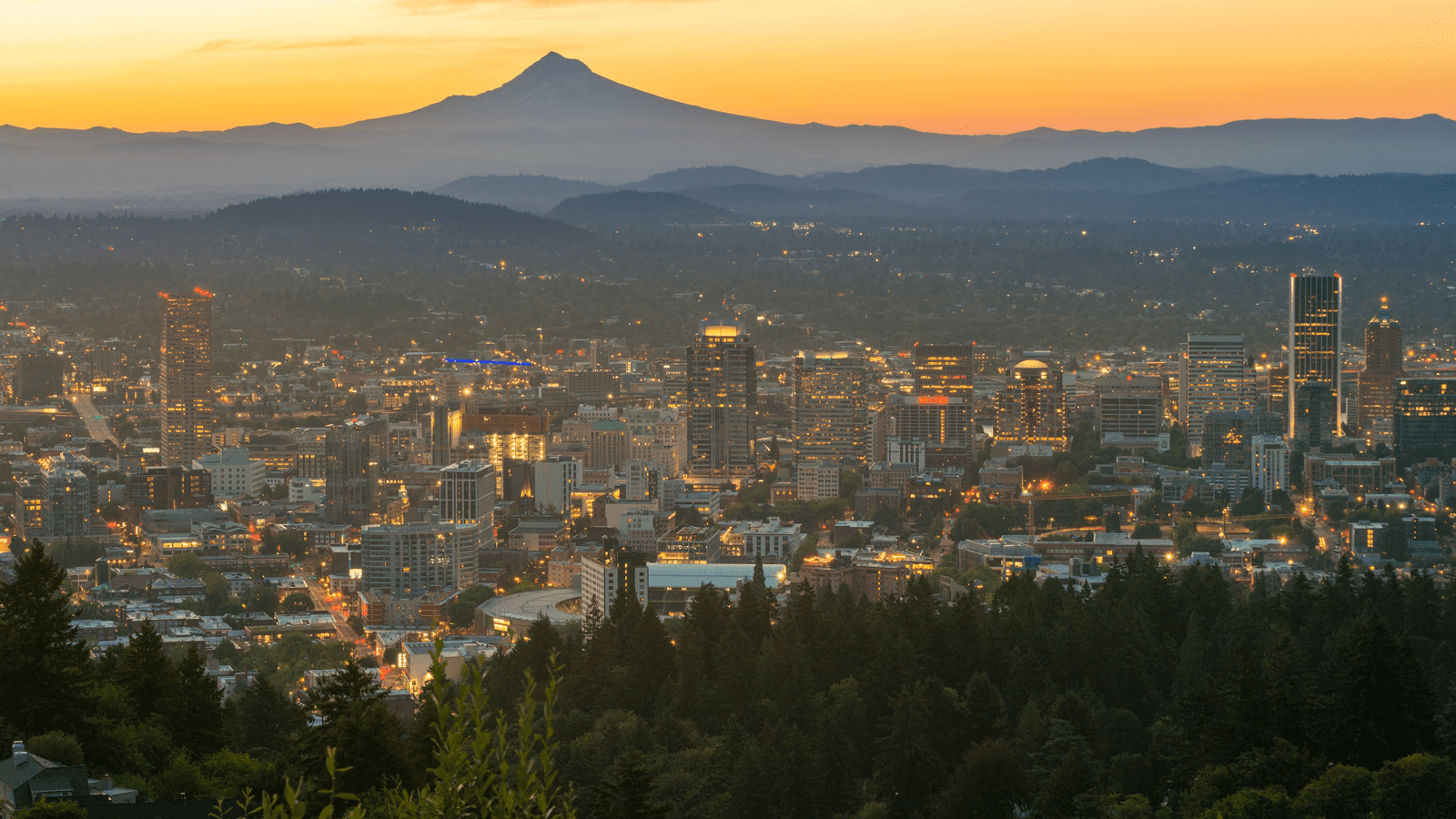

Oregon is at the vanguard of this movement. In 2020, when the state’s ambitious climate goals ran up against stubbornly high car emissions, Democratic Governor Kate Brown charged state officials with finding a solution. One initiative to emerge from her executive order is Climate Friendly and Equitable Communities, a set of urban planning rules adopted in July by the state’s Land Conservation and Development Commission.

The new rules aim to create denser communities that offer a variety of transportation options, making it easier for residents to meet their daily needs without driving. Among the requirements: local governments throughout the state must allow taller buildings in designated areas, reduce the number of parking spaces required in new developments, and provide more resources to support walking, cycling, and public transportation.

“Legalizing the ability to live and work closer together, and have cities be able to develop in this walkable way that they used to 100 years ago is a really big step forward,” said Catie Gould, a climate and transportation researcher at Sightline Institute, a think tank focused on the Pacific Northwest. The parking reforms in particular remove critical barriers to sustainable development, she said.

Gould cites Portland’s Northwest District, which was first developed in the 1800s, as an example of the kind of streetscape the new regulations aim to create. “The Northwest District has never had parking requirements. It has a lot of older brick mid-rise residential buildings. It’s a very walkable neighborhood,” she said. “I have friends that love living in Northwest, and they love all the places they can walk to, having grocery stores and restaurants and shops nearby.”

A Growing Trend

Driven by concerns over climate change, affordable housing, and social justice, other states and cities across the country are also enacting significant land use reforms.

In the past few years, California and Maine have effectively eliminated single-family residential zoning; other states, including Republican-led Nebraska and Utah, have made similar proposals. In October, California eliminated minimum parking requirements near public transit.

Meanwhile, local governments are using zoning to address a wide variety of issues. Minneapolis made headlines around the nation in 2019 by eliminating single-family zoning, and other cities have followed suit. Coastal communities like New York City and Norfolk, Virginia, have adopted new codes aimed at increasing resilience. These trends are being seen also in small communities like Carrboro, North Carolina, which banned new drive-through windows in its city center.

An Under-the-Radar Solution

But while these measures have important implications for greenhouse gas emissions and climate adaptation, many of them don’t even mention the environment. As a recent Harvard Law Review article noted, discussions surrounding recent state-level reforms have largely avoided mention of climate change, focusing instead on affordable housing.

The failure to connect the dots between land use and climate change is hardly confined to these examples. Consider Evan Manvel, a climate mitigation planner in Oregon’s Department of Land Conservation and Development, who helps lead the Climate Friendly and Equitable Communities initiative. Even among colleagues, he sometimes must explain why land use reforms should be a priority when other climate solutions — electric vehicles, for example — are much better known. (His response: Since it will take decades to transition the entire fleet, and since much of the energy used to power electric cars still comes from dirty sources, EVs alone won’t cut it.)

Land use is “in some ways a more complex and less direct and longer-term tool to take on climate pollution than some of the things we’ve traditionally done,” Manvel said. “I think it’s harder to see how exclusionary zoning and other land-use decisions have caused pollution — and you see pollution coming out of a smokestack at a coal plant.”

Some Legal Thing … and ‘A Niche Concern’

Land use policy’s role in climate solutions has been obscured by its bureaucratically byzantine nature.

In the United States, land use decisions are largely made by local zoning boards; state-level interventions are a relatively new phenomenon. Zoning codes vary by municipality, leading to a mind-boggling volume of extremely specific rules across the country.

“Within a single jurisdiction, the zoning code can be a couple hundred pages long — so it’s regulating minutiae,” said Jonathan Rosenbloom, a professor at Albany Law School and the director of Sustainable Development Code, a research and editorial platform focused on planning best practices. “But then we have to compound that by 39,000 local governments across the United States. So the complexity of talking about zoning gets really difficult really fast, because we have many iterations of it, and we have many different things that it’s regulating.”

Sonia Hirt, dean of the College of Environment + Design at the University of Georgia, said that while interest in zoning has grown dramatically since she started writing a book on the topic a decade ago, it remains a niche concern.

“When’s the last time anyone talked to you about zoning at the dinner table?” she asked. “It seems like something technical and just an instrument — it’s some legal thing, and who cares? But the truth of the matter is that it’s very influential because it allows you to live a certain way, or not live a certain way.”

For example, many cities’ zoning codes specify that the only new construction type permitted in residential districts is detached single-family housing: no apartment buildings, townhouses, or other housing types, let alone grocery stores, doctors’ offices, or other commercial uses. What’s more, these codes often require that new homes meet or exceed certain requirements for square footage and lot size.

These rules, referred to as exclusionary zoning, effectively bake in sprawl. Rooted in a long history of racial, socioeconomic, and religious discrimination, they push local residents into a car-dependent lifestyle by making everyday activities — visiting a community center, eating out, going to the gym — virtually impossible without driving.

And exclusionary zoning is only one example of the myriad ways that land use policy shapes Americans’ everyday lives while impacting greenhouse gas emissions.

“Anytime you step out your door, or even anytime you move inside your own house, many of the things that are affecting how you move about your day, what you eat, how you eat it, where it comes from, what transportation you take, whether your lights are fueled by solar or wind or gas or oil — all those things are impacted by zoning,” said Rosenbloom.

Rethinking Zoning’s Legacy

The familiar low-rise, car-centric communities found across much of the United States can make the American land use paradigm seem natural, almost predetermined. But in fact, there’s nothing inevitable about it, according to Hirt.

“We kind of made up the system over the last hundred years, and now it’s become so customary to us that I think we just don’t really think about it,” she said.

She points to Europe to demonstrate how things might have turned out differently. Municipal zoning was born in Europe in the late 1800s, then imported to the U.S. around 1900. Within a few decades, the American model evolved crucial differences. To this day, compact districts with a mix of building types — a common formula in Europe — are less likely to be allowed under American codes. Instead, U.S. zoning is much more likely to dedicate large swaths of land to single uses: residential, commercial, or industrial.

In particular, the U.S. places unusual emphasis on single-family residential districts. In some jurisdictions, more than 90% of land is dedicated to detached single-family homes. “That really sets apart American zoning from the way it’s practiced in other countries,” Hirt said.

Legalizing Traditional Communities

According to Oregon’s Evan Manvel, many of the land use reforms now being enacted are essentially a return to the days before 20th-century zoning innovations reshaped the American landscape. “A lot of this is reinventing the wheel of traditional housing types that we made illegal,” he said.

But he emphasized that these changes also align with contemporary demographic shifts that have increased demand for less-expensive homes in denser, more walkable neighborhoods. “Fifty years ago, it was nuclear families, and that was 40% of households. And now it’s about 20% of households, and almost a third of households are single-person households,” he said.

He believes that the tangible benefits land use reform can bring to people’s everyday lives offer a powerful incentive to make it part of the standard climate solutions toolkit.

“It’s better housing choices. It’s the ability to walk to get your groceries. Or being able to not chauffeur your kids everywhere, and they can bike to a neighbor’s,” he said. “So hopefully, the co-benefits of working on land use will really help move it forward as a way to also reduce climate pollution.”

Zoning and related development standards are absolutely central to how urban areas develop. If you compare two countries with generally similar US derived land use planning systems – ROK and Japan – you see the former has ultra dense urban areas, with abrupt transitions to rural areas, while in the latter the cities sprawl over vast areas. The key difference between the two is that the Koreans area much more proactive at taking land into public ownership and using zonal regulations and direct intervention while the Japanese find this very difficult due to land ownership splintering and weak eminent domain laws. The Koreans are also much keener on maintaining agriculture zoning than the Japanese, for reasons that are obscure to me given both those countries histories. Of course, both countries had a blank slate start thanks to their most influential urban planner, Curtis LeMay.

But often people confuse density with high rise, or even apartments. You can achieve very high densities with well designed terraced housing developments (most of the Netherlands, for example), and appropriate infills (for example, rear mews developments in existing large plot suburbs) can be surprisingly effective at creating far more diversity of house type and density. More often than not the core problem is not exclusionary zoning, but minimum car space and garden size regulations, which can result in a huge waste of space. The amount of land devoted to car storage in the US is staggering, much of it almost entirely unused.

Just a couple of comments:

1. I found the tone of the article amusing. In several spots, I felt as if the author was thinking “how dare they not cite climate change as their reason even if they are doing the right thing anyway.” The author didn’t seem to realize that it might be more politically advantageous that way.

2. I am totally in sync with Yves comments on walkability etc. My elderly parents are severely limited in their mobility. In addition, a lot of higher density housing is being built here in So Cal, but the preference currently seems to be for 2-story townhomes, none of which are suitable for anyone who has issues with stairs. Back in the 70’s and 80’s a lot of condo complexes had 2 story buildings with a single story unit on each floor so 1/2 the units had no stairs at all. With the increasing elderly population, anything single story sells at a premium here.

I still don’t see a growing elderly population as an argument against walkability. Just because walking might be the default mode of transportation, doesn’t make it the only one; likewise, cars aren’t the only way for the infirm to get around.

If anything, I’d say that vastly increased walkability and density would greatly help the elderly, because it would help recreate the social bonds that have been alienated away by our current development pattern.

I also found the tone amusing. If you read any consultancy reports or white papers from the last decade or so even remotely related to sustainability or technology, it becomes obvious quite quickly that a) EVs were never intended as 1:1 replacements for passenger cars, instead being destined for sharing fleets in a ratio of 1:20 to 1:50, and b) travelling long distances is perceived to be a very elite activity in the near future. The level of agreement on those points is matched only by the shared acknowledgment that it will be a politically difficult transition.

I’ll just point out that zoning doesn’t just restrict housing, but also commercial activities. Having a walkable environment is just as much a matter of having places to walk to as having dense housing.

The amount of land devoted to car storage in the US is staggering, much of it almost entirely unused.

A number of years ago my boss was an architect (Canadian) who said that the first project he worked on as a junior architect was a residential one in the Detroit suburbs. He was totally shocked at the parking requirements.

Regarding Portland, Husband sent me this yesterday, writing that ‘Portland seemed to be having a hard time’ in the news lately:

https://i.redd.it/eqhfunr16u2a1.jpg

That’s this story about owner Marcy Landolfo and her store, Rains PDX:

https://www.foxbusiness.com/retail/portland-store-shuts-down-posts-blistering-note-front-door-slamming-rampant-crime-city-peril

Also reported in the Portland Business Journal, but there it’s behind a paywall.

So in recent years my town has transformed from a doughnut surrounding a downtown hole to a nicely uniform residential pastry that still has a downtown grocery hole. Which is to say it’s not just about zoning but also about a commercial landscape that has evolved to shape itself around cars. Those people downtown get to walk to the main library and pricey restaurants and new nightlife but that’s about it. If they are fit cyclists they would still need to ride several hilly miles to find a grocery store and on dangerously busy streets. We are now getting a network of pedestrian/cycling trails but slowly.The “new urbanism” is more about giving young people a hipper lifestyle option than about AGW–at least around here.

We did have a coop grocery for a few months downtown but it went bankrupt. Larger chain groceries want to have easy customer access and not just the limited downtown walking population. A nearby city has a Publix more or less downtown but surrounded by a parking lot.

Here’s suggesting a better short term solution to reduce huge US carbon pollution would be higher CAFE standards more than the unicorn of widespread EV adoption. But as always special interests–Detroit–stand in the way.

“…a better short term solution to reduce huge US carbon pollution would be higher CAFE standards more than the unicorn of widespread EV adoption. But as always special interests–Detroit–stand in the way.”

DingDingDingDing! We have a winner!

Saw a Hyundai EV on display last weekend in Atlanta. Nice looking car and not built by the Elon. $58,000+. Less than 300-mile range. In the South, that just will not do. Or in most of the country.

My medium-size southern city had a local grocery store downtown for 6 months. Not a co-op but a good idea, with local meat and produce. Poorly executed, missed the market they aimed at, if they were aiming at people conscious of the climate crisis. Alas. We tried using it, but the 4-mile drive to Publix (now an 8-mile drive to the replacement store) was still necessary. The good thing is that I go only once a week since the pandemic began.

Plenty of nice, practical hatchbacks available in UK that do 50+ miles to US gallon. Why buy an EV? Because you can’t get those cars in USA… hmm.

After 30 years of the urban sprawl dominated capital city of California, sacramento, I moved to the highly walkable capital city of uruguay, Montevideo. A simple solution to the problems I saw in Sacramento would be simply to allow some businesses to be located within the suburban sprawl.

Thanks for the Sacramento shout-out. As someone who was very close to that region’s process I can tell you big changes are coming (as they have been for decades now).

As is typical for many older cities, the old (say pre-1950) areas are walkable. The account of sprawl above neglects to mention “white flight” as one of the origins of the changes that make it unwalkable. Pedestrians, especially pedestrians of color are icky.

The state of California really made minimizing Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) a factor in planning/development, and (very big!) mandates “Complete Streets” (street design that accommodates pedestrians). Traditional, pedestrian-friendly, mixed-use neighborhoods cut VMT roughly in half.

Often I’ve heard “But sprawl is what people want.” That’s a bare-faced lie. The most valuable real estate in the region is pedestrian-friendly mixed use — the area around McKinley Park…a beloved public space. I know I can’t afford to live there. Elsewhere in the country, premiums paid for such neighborhoods range from 40% (Kentlands, MD, Orenco Station, OR) to 600% (Seaside Fl). People pay premiums to leave sprawl when there’s an alternative.

Of course sprawl socially disenfranchises the too-young-to-drive and the too-old-to-drive, and driving everywhere builds the exercise out of civic design. Only ten minutes of walking daily leads to far fewer late-life health problems. Having to own a car is one of the most regressive taxes known to man.

There are $50 million worth of disconnected sidewalks in the region, and not enough density to support viable transit (> 11 units / acre — a little more than duplex — is the threshold). So people can’t walk to transit stops, and there aren’t enough people in the neighborhoods to make good transit have riders. Regional Transit is a lame, third-rate operation with buses that arrive roughly every three hours. We can’t even get bus service to the airport. (Mo’ money for Uber, though!). Oh yeah, we have light rail too, but that doesn’t go many places and has similar problems.

New developments are a mixed bag. Nearby Citrus Heights is redesigning their flagship mall Sunrise Mall to include a hotel. They also promise more housing….something I’ll believe when I see it. (All discretionary tax revenue in the region comes from retail sales taxes)

Why so skeptical? Several of us added pedestrian-friendly guidelines to the County’s general plan 30 years ago. These were supposed to be considered whenever developments exceeding five acres were proposed. They weren’t. A friend from nearby Folsom also reports new development there ignores the state’s new requirement for “Complete [pedestrian-friendly] Streets” too. So talk is cheap.

I’ve been trying for more than 30 years to get this pattern to change without much success. It’s been pretty bad all that time, but the worst feature is what “developers” (i.e. “land speculators”) do. They can buy outlying ag land for a few thousand dollars an acre, then, with the approval to develop, sell it to builders for 50 – 100 times what they paid for it. If they exchange out of the transaction, they can own income producing property (commercial, or apartments) without paying a nickel in income tax.

By way of contrast, German developers have to sell the land at the ag land price to the local government, then re-purchase it at the development land price. All of that egregious profit — called the “Unearned Increment” — accrues to the benefit of the public. And Germany has some pretty nice public amenities.

Meanwhile, back in Sacramento, this is land speculator paradise. The late former County Supervisor Grantland Johnson once told an audience that Sacramento is widely acknowledged throughout the state as the most in the hip pocket of those speculators. Not a contest we’d like to win.

This whole zoning question is tightly intertwined with racial politics and also with class prejudice. I live in Ohio near Akron where countless proposals are rejected because they might upset nice all-white, comfortably-monied, demographics. A panoply of regulation exists, most importantly zoning, municipal, and school district boundaries. The courts and the legislature maintain it. It is a sick system in a sick country.

Who will cut the Gordian Knot? It won’t be a single cut by the sword of Alexander. I wish I had something optimistic to say.

My State, Virginia, is a Dillon Rule that leaves many land-use decisions to the State Legislature- a legacy of the reaction to reconstruction. It is unlikely that the PTB will permit much in the way of rational local zoning.

On the other hand, it means that Virginia could force the municipalities to rationalize their zoning codes, which isn’t always a given in every state.

Back in the ’90’s when sustainability, New Urbanism and grid streets became a thing, Portland produced a Pedestrian Design Guide. It was all about urban density, walkability, connected streets, public transit, air quality and traffic minimization. After decades of slavish motor vehicle worship, this was quite a revelation. In my mountain city where we enjoyed the benign Iron Rule of the Developers, these sort of enlightenment guidelines were a total non starter…simply a discussion item for the planners over coffee break. Then it was on to signing off on whatever loop-and-lollipop, walled subdivision design plans the developers were submitting. There is an oceans worth of difference between guidelines and rules.

“The new rules aim to create denser communities”. I know I will be going very much against the grain on this site but this article from Yale is another version of the same thing we heard years ago from them: Transit oriented development. These buzz words are created by academics that represent the real estate lobby and ear worm themselves into the public lexicon over several years until, without proof, they are adapted as truth by the public. Once the adaption is complete the local developers across the nation present this “truth” to communities to do what?… overturn their zoning laws to build density. Why do they want density? To make more money. What do they leave behind…problems that the community must pay for in perpetuity. This is so clearly seen in towns that have been in developer crosshairs for the past 100 years.

This article and some of the accompanying comments display a complete lack of understanding of the original purpose of Zoning Laws. A single family home owner has no more rights and no less rights, than a commercial building owner. Each are equal under the law. This concept of equality is the

bedrock of society in every community. It makes us neighbors rather than competing users. It was set up years ago so that everyone could feel secure in making what for many of us is the single most important

investment of our lives. Whether you make a Commercial investment , an Industrial investment, a multi-family investment or a single family investment you are protected. No one person or corporation or created village entity or governmental body can take, amend, obliterate or desecrate your rights.

The law says you are the equal to all of them.

Funny, no one seems to care about laws anymore, they are so inconvenient when you want to make money.

Particularly when the ear worms take over. Villages are only too happy to take away your property rights and transfer them, without recompense, to a developer who builds, takes the cash, and leaves the town to sort out the problems of density. Forever.

What’s different this time with Yale? They have added the new twist of climate change to their pro-developer argument. Everybody is against climate change and rightly so. However, Yale wants to make you the problem of climate change and their solution to climate change? Let the developer make as much as he possibly can on your back. I’m no scientist but I don’t think the neighbor across the street going to the grocery store once a week can hold a climate candle to the devastation caused daily by the thousands of ships wandering the globe, the thousands of airplane flights an hour circling our cities, or the thousands of rocket flights puncturing the atmosphere to support 5,000 satellites. Maybe the gas leaking from all the old oil wells, or fracking sites or someone intentionally releasing untold amounts of gas into the atmosphere while destroying critical infrastructure for political gain could be a much bigger problem.

Thank God Yale has straightened us out and told us not enough density is their solution for the world’s climate change problem. How’s that working out in China?

Like good old Professor Michael Hudson says; it’s all in the nomenclature. If you can make left mean right and right mean left and make the man on street agree…well… you have earned the right to fleece him for all he is worth.

This approach to land-use planning (trying to cut down on driving by eliminating parking spaces) is ridiculous. Consider the impact.

We live in a planned community in Northern Virginia. The garageless, lower-end townhouses only have enough parking spaces for two cars for each dwelling under the assumption, one supposes, that two people work and need cars. The garageless, lower-end apartment complexes likewise limit parking to two marked/reserved parking spaces per dwelling. The intentional lack-of-sufficient-parking arrangements are enforced by towing.

This puts a damper on visiting anyone in these low-end housing arrangements. If one wants to visit someone, it is often necessary to walk up to two or three blocks on unlighted streets and sidewalks. This creates a prison-like atmosphere with strict limits on socializing. It becomes a practical impossibility to entertain friends or relatives.

On the contrary, the upscale townhouses and stand-alone houses have plenty of parking in driveways and on neighboring streets. Our driveway can hold four cars with unlimited parking on a side street a few hundred feet away.

I feel for the people who are denied a social life due to limited parking. This was not done as a reaction to climate change. The reason was economic: it was done to jam more living arrangements into more limited space to meet zoning requirements for low-income housing. I know lower-end townhouse owners and apartment renters who were unaware of the draconian parking arrangements until they moved in … only to find their cars towed one night for parking in unassigned spaces.

This lack of parking creates an anti-social “prison-like” atmosphere for these people. It would seem that just zoning laws would require “equal parking” availability in the upscale and downscale parts of town. This may seem like a small thing but it is not.

Thanks for giving knowledge