Yves here. On the one hand, it’s instructive to see a solid program that addresses concrete needs, here for food, continuing to operate. But it’s also noteworthy that it in New York City, it continues to be oversubscribed. And with so many restaurants and retailer having extra food, the limiting factor isn’t supplies as much as having staff and trucks to get to the fridges.

I hope that THE CITY publicizing the free fridge program might lead other communities to take it up.

By Jonathan Custodio. Originally published at THE CITY on Nov 30, 2022

Selma Raven, left, and Sara Allen place vegetables in a community fridge in Riverdale in September.. Jonathan Custodio/THE CITY

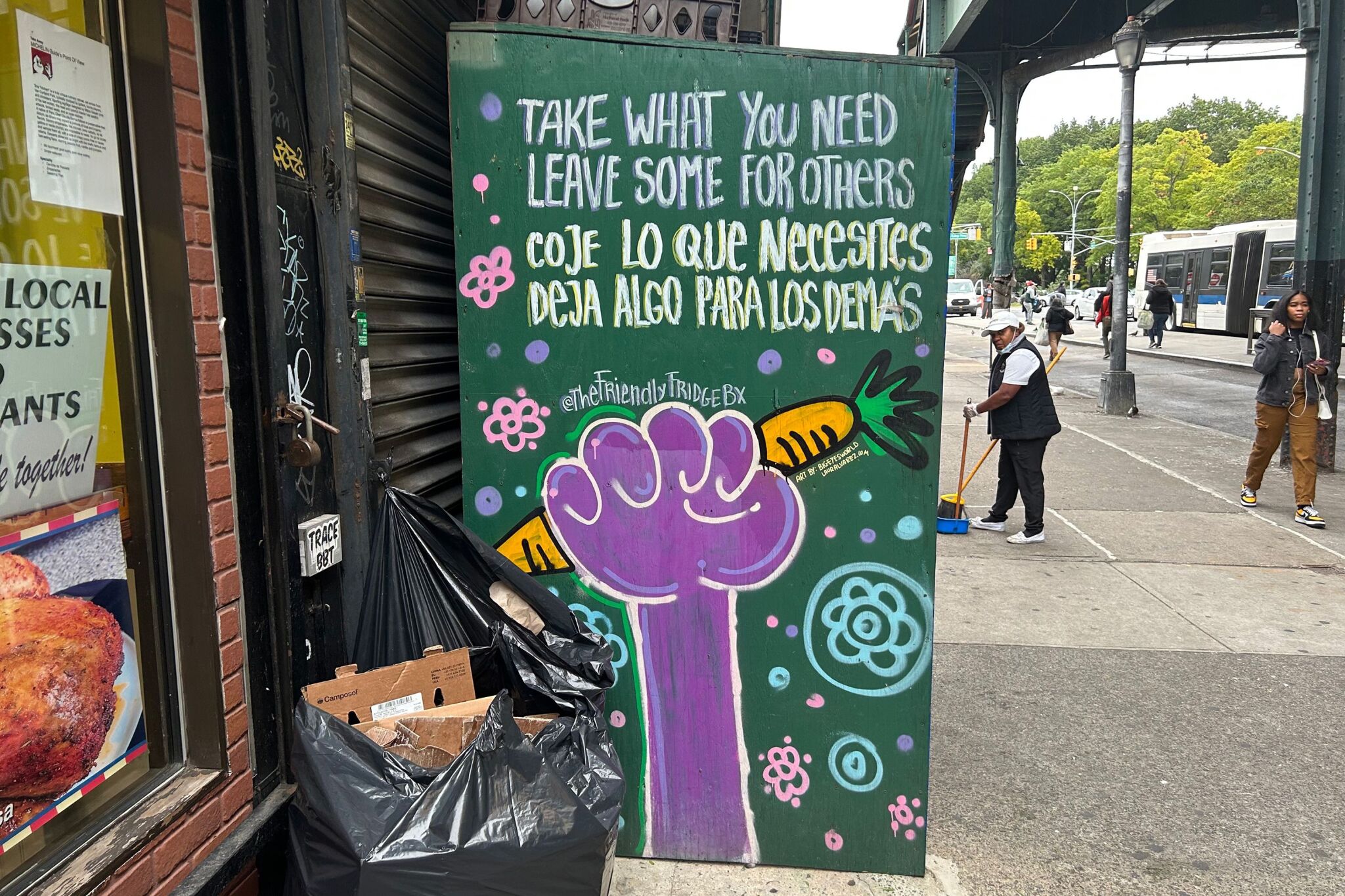

Community fridges became a vital stopgap during the pandemic, providing free produce, prepared meals and even clothing to the neediest Bronxites. Now, the volunteers who run them wonder how they’ll keep this community resource going, as fridges are routinely emptied several times a day.

Tony Marquez, a Riverdale resident of eight years, stopped by The Friendly Fridge on 242nd Street and Broadway as he commuted home recently and told THE CITY the fridge has been a big help to his family.

“There are seven of us,” Marquez said in Spanish while carrying a bag of groceries and a hoodie he picked up from the fridge. He supports five children. “Everything helps, my brother. I’ll take them with me. I need them.”

Coach Will, who preferred not to give his last name, stopped by after working out in nearby Van Cortlandt Park. He says he stops by the fridge “all the time.”

“I need the vegetables because I had a stroke,” Will told THE CITY on a September evening as fridge users sifted through strawberries, radishes and avocados. He said he had the stroke right before the pandemic began and has been going to the fridge ever since it popped up in May 2020.

“I don’t eat brussels sprouts, but now I got to eat them since they gave me a bag,” Will said.

Persistent Needs

Only a couple of community fridges existed in New York City before the pandemic, estimates Sara Allen, 47, an engineer manager for a startup who co-manages The Friendly Fridge. The popularity of community fridges soared once COVID highlighted food insecurity nationwide.

In the U.S., the number of fridges skyrocketed to over 200 in 2020 from 15-20 before the pandemic started, according to Ernst Bertone Oehninger, one of the founders of international community fridge network Freedge.

Oehininger, who serves as Freedge’s treasurer and works on its mapping, acknowledged that it’s hard to keep track of all the fridges but estimated that there are more than 500 fridges in the U.S. right now.

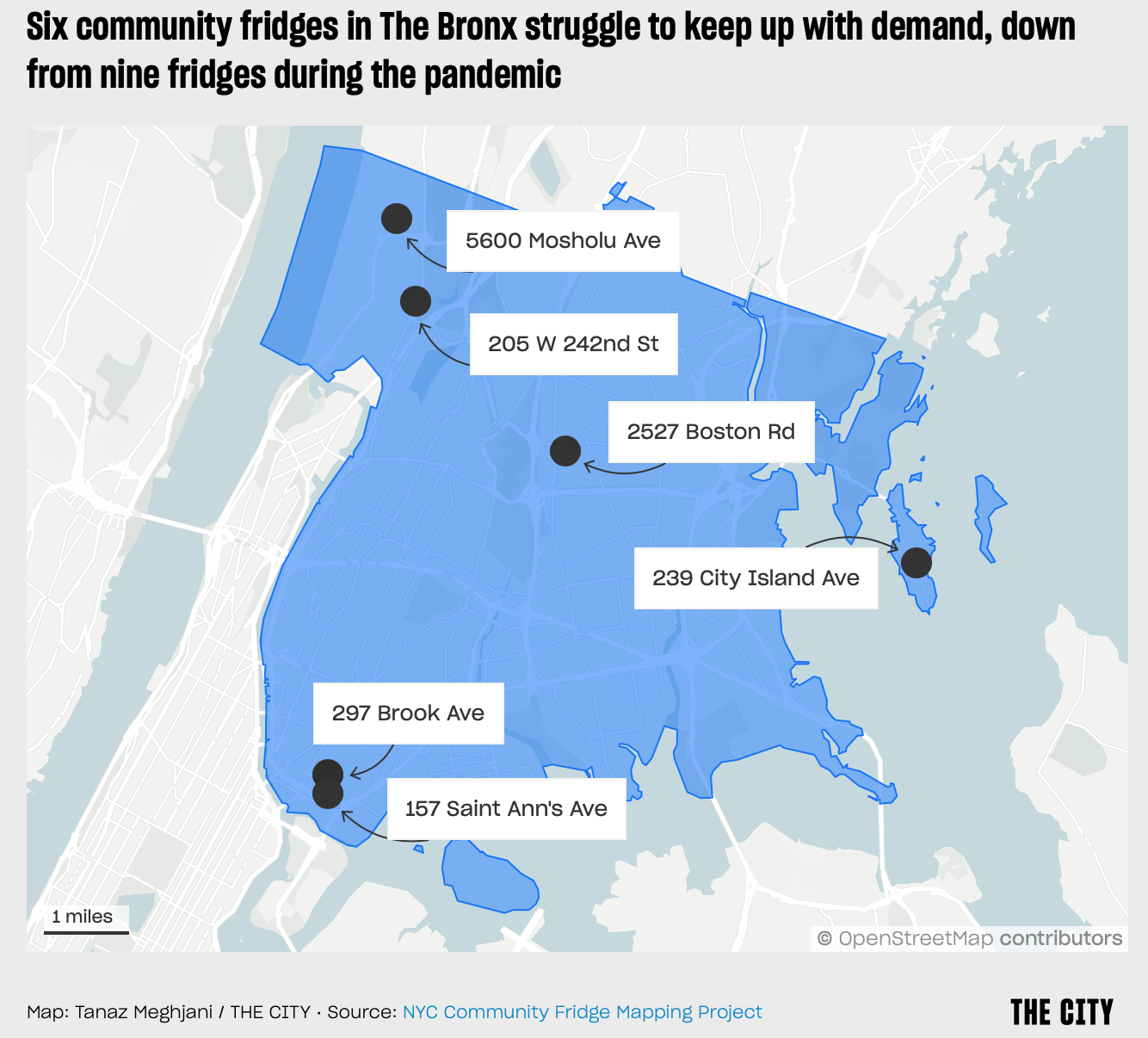

There are at least six community fridges in The Bronx now, down from about nine since the winter of 2021. Lack of consistent funding or closure of businesses supplying electricity forced several fridges to shut down, including ones in Soundview, Parkchester and Bedford Park.

At the remaining fridges, volunteers are scrambling to meet persistent needs.

“It doesn’t really address food insecurity,” said Selma Raven, 56, a special education teacher in The Bronx who co-runs The Friendly Fridge with Allen. The demand is overwhelming, Raven said. “It will fill and empty several times a day.”

Raven and Allen work at the fridge daily, and they estimate around 250 visitors grab something from the fridge every day.

Allen usually handles the fridge in the morning before logging in to her job because she works on West Coast time. She and Raven receive calls from restaurants to pick up food at all hours of the day. Allen estimates that they will receive about six to eight thousand pounds of food for the fridge per week.

The fridges are coordinated by local residents supported by larger groups. The Mutual Aid Collective, for example, works with fridges in City Island, Riverdale and Allerton. If a fridge has a ton of prepared meals, its coordinator will reach out to another fridge partner that may be running low on food.

Grassroots Grocery, a fast-growing nonprofit organization that coordinates deliveries to community food sources in The Bronx and Upper Manhattan, manages two fridges in Mott Haven and one in Co-Op City. The organization taps community volunteers to ensure the fridges are well-maintained and regularly stocked.

Most fridges are working with a tight budget, according to Ariadna Phillips, an organizer in The Bronx with the Mutual Aid Collective.

“Most of the fridges have operating budgets under $1,000,” she said, adding that food availability isn’t the biggest problem facing fridges. “It’s not the food that’s missing. It’s the transport and distribution.”

Emptied Out Quick

Raven and Allen will stock the fridge through pickups from pantries, restaurants and schools. They get produce and other food in bulk, along with fully prepared meals. They partner with seven schools and four food pantries in The Bronx, all within a one-mile radius, Raven told THE CITY.

Sometimes they will get calls from pantries in Manhattan offering perishable food that needs to be picked up quickly, but are not able to make the trip.. Or they’ll get late calls from restaurants with bags of food available. This is where a driver can come in handy.

“The on-the-fly nature of food rescue makes scheduling difficult,” said Doug Silver, founder and executive director of Gotham Food Pantry, contrasting it with the smoother schedule of a soup kitchen or food pantry. “The number of rescues that we’ve lost because somebody — we’re told an hour before that there are 3,000 pounds of apples on this pier. Well, I can’t really do anything with that right now.”

Many fridge users ask if they can lend a helping hand to the operation, said Raven. But while more volunteers to help with food distribution and fridge maintenance is helpful, transporting food from pantries and restaurants is the biggest obstacle.

Like most volunteer service providers, funding is a major issue for fridge operators, who need money to pay for transportation. Those expenses can include hiring delivery drivers, covering gas costs, cleaning and packaging supplies or paying someone to help manage the fridge.

The Friendly Fridge has an average operating budget of $570 per week, including transportation, Allen told THE CITY via text. That does not include the $600 weekly average spent buying hot meals from local restaurants: Allen said they are “working very hard to increase that number.”

“I want to pay a living wage to a fridge organizer,” said Raven, noting she would love to have enough funds to pay someone else to coordinate the fridge and ease some of the burden on her and Allen.

“At some point” the work needs to be more self-supporting, she continued. “How sustainable is this model?”

Neighborhood Outlets

Part of what keeps the fridges going is neighbors — and sometimes, their businesses too.

The Friendly Fridge is in front of Jerusalem’s Bar and Grill, whose owner allows Raven and Allen free use of electricity to power the fridge. Many community fridges rely on other storefronts for the same.

When operators first set up fridges, it was not uncommon to hear residents and business owners say it was a bad idea: that fridges would be subject to vandalization or worse. But those concerns have subsided, Raven and Allen said. Some previous skeptics have even become helpers. A nearby Riverdale deli owner who was pessimistic at first now routinely drops off leftover bread at the fridge, they said.

Community fridges often rescue leftovers and food headed for the trash from local restaurants. The restaurants’ proximity to fridges reduces delivery costs and other headaches. Ready-to-go meals are more appealing to fridge-goers, said Raven, who noted these are prioritized for people experiencing homelessness.

Silver of Gotham Food Pantry is all in on getting unused food from local restaurants transferred to fridge shelves and other food rescue projects.

“Local retailers can beef up food sources,” Silver said. “I think every restaurant or food retailer that opens in the city, as a policy change, should have a designated food rescue partner … just the way you have to have a health license and you can get graded on that. I think donating your food is a public health issue.”

Several bills aimed at addressing food waste have been introduced at both the federal and state level.

The Food Donation Improvement Act incentivizes businesses who pay for transport of donated food by offering a tax deduction. The state passed an act in 2020 that supermarkets over 10,000 square feet have to donate their food. The City Council has sought to curb food waste under a 2013 law that penalizes food-related businesses of certain square footage for failing to separate organic waste but, as of July, as THE CITY reported, the follow-through and enforcement remain unclear.

In the meantime, volunteers in The Bronx are stocking free fridges in any way they can. While food pantries often limit their distribution to certain hours, Raven notes, the fridges often pick up food from pantries or schedule impromptu deliveries from them. That’s vital, she said.

“We have vulnerable populations. They cannot stand on that line,” she said.

Silver said a fridge’s strongest source of power is the community maintaining it. “Once food arrives, people descend,” he said. “We can’t discount the human element of what makes a fridge function.”

How to Help Local Free Fridges

You can find and support a community fridge near you anywhere in New York City using this Fridge Finder app.

To donate, you can reach out to the following Bronx community fridges through their websites or Instagram pages:

We have several community fridges in the Bed-stuy/crown heights sections of Brooklyn. Many local retailers routinely stock them and at times I’ve seen lines of people awaiting the next re-stocking. There’s persistent need, it’s obvious.

The ad-hoc, just-it-time needs of sourcing lots of available supply sounds like a particularly difficult challenge, but one the city could surely address with not that many resources. Hire a few full time bike delivery drivers/riders per borough? Amazon and UPS already rely on their relative advantage over cars/trucks in the city, especially since bike trailers enable pretty impressive hauls.

We have these here in Tucson as well.

Matter of fact, this city is kind of a share-it hotbed. It’s the place where the Freecycle program got its start. Link:

https://freecycle.org/

We also have quite the network of Little Free Libraries and one of my favorite places in town, the Free Table. Being a share-it hotbed, we have many, but my go-to is just 1.4 bicycling miles away from the Arizona Slim Ranch. I’ve taken all sorts of things there, and I’ve also found plenty of interesting stuff.

Share on, people! It’s fun!

Chiming in from here in Richmond, VA, too. 10 current active fridges, all placed in areas accessibly by public transportation and heavily promoted on Social Media. Near as I can tell, it has been a fantastic and well supported resource. You can donate actual fresh food or $$. We had one case of someone maliciously unplugging the fridges overnight during the summer this year, but since then, no issues. I am glad these exist (right along with our Little Libraries too) and I have sent $$ their way.

Seen them all over New England, even in small town Vermont. Is there a part of the country that doesn’t have them?

I know this is supposed to be an uplifting piece, about solidarity and community and all, and to a certain extent it is, but for me, to address destitution with public fridges in the street, in the richest country in the world, is absolutely horrifying.

I grew up in a small Communist country, and at the time I thought we were the most persecuted human beings on Earth because we didn’t have blue jeans and free speech. Little did I know.