Yves here. Gabriel Zucman came to prominence with his study on tax havens that became the book The Hidden Wealth of Nations. Zucman concluded that 8% of global wealth was held in tax havens, and 6%, meaning 75% of the 8%, was in fact shielded from the tax man.

Most people think of tax havens as being primarily the device of shady oligarchs and third world dictators but the biggest users are major corporations. Nicholas Shaxxon, in his book Treasure Islands, used a early chapter to describe how corporations shifted income out of Africa to the degree that Africa was a net capital exporter.

Zucman and his co-author Ludwig Wier focus this post on the findings of new paper on whether EU and US efforts to curb tax haven use have had much impact. They conclude not.

By Gabriel Zucman, Professor of Economics University Of California, Berkeley and Ludvig Wier, Head of Secretariat Danish Ministry of Finance. Originally published at VoxEU

The world has been trying to curb profit shifting to tax havens for a decade, but consistent time series evaluating the impact of these reforms have been largely absent. This column uses a new time series of global profit shifting covering the 1975–19 period to estimate that the fraction of multinational profits (made outside of the headquarter country) shifted to tax havens increased from less than 2% in the 1970s to 37% in 2019, resulting in a tax loss of roughly €250 billion.

In June 2012, world leaders at the G20 meeting in Los Cabos attested to the need to curb the corporate practice of using tax havens. The OECD was put in charge of developing a plan that ended up consisting of 15 tangible actions that should significantly limit abusive corporate tax practices. Three years later, the G20 adopted the plan officially and implementation began across the world in 2016 (Djankov 2021).

In the immediate aftermath of this landmark agreement, leaks of questionable corporate tax practices flooded the ether (the Panama Papers, Paradise Papers and many more). These bolstered public outrage and led to further political action across the world. In the US, the Trump administration passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in late 2017 that almost halved the corporate tax rate in the US and cracked down on profits located in tax havens, both actions intent on lowering the incentive to shift profits to tax havens. Meanwhile Margrethe Vestager – named “the tax lady” by Trump – started going after EU member states granting preferential tax deals to multinationals. Finally, lowering profit shifting to tax havens became an explicit part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with SDG 16.4.1.

So, did all of these plans work? Was profit shifting to tax havens curbed by these global efforts? In a new paper (Wier and Zucman 2022), we investigate this and find that it was not. The increase in artificial profit shifting to tax havens by corporations have been relentless since the 1980’s until today.

Quantitative Estimates of Global Profit Shifting

A body of evidence suggests that multinational companies shift profits to tax havens (e.g. Bolwijn et al. 2018, Clausing 2016, Crivelli et al. 2015, Tørsløv et al. 2022). Until now, however, we have not had a good sense of the dynamic of global profit shifting. Have corporations reduced the amounts they book in tax havens since 2015, or have they found ways to eschew the new regulations? A number of studies provide estimates of global profit shifting, but they typically do so for just one reference year. Moreover, because these studies rely on different raw sources and methodologies, their estimates are not directly comparable, making it hard to construct consistent time series by piecing different data points together.

This limits our ability to study the dynamics of profit shifting and to learn about the effects of the various policies implemented to curb it. This paper attempts to overcome this limitation by creating global profit shifting time series constructed following a common methodology. Our series allow us to characterize changes in the size of global corporate profits, the fraction of these profits booked in relatively low-tax places, and the cost of this shifting for governments of each country.

Our starting point is the estimates from Tørsløv et al. (2022), which are for 2015. Building on the same sources and applying the same methodology, we first extend these estimates to cover the years 2015 to 2019, a period that includes the base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) process and the US tax reform of 2017. We then construct pre-2015 series back to 1975, which allows us to capture the decades of financial and trade liberalisation that saw a dramatic rise in multinational profits. Due to the lack of some of the input data required to implement the full methodology of Tørsløv et al. (2022), these pre-2015 series are based on additional assumptions and have some margin of error. However, the main quantitative patterns that emerge from these series are likely to be reliable.

Our Main Findings

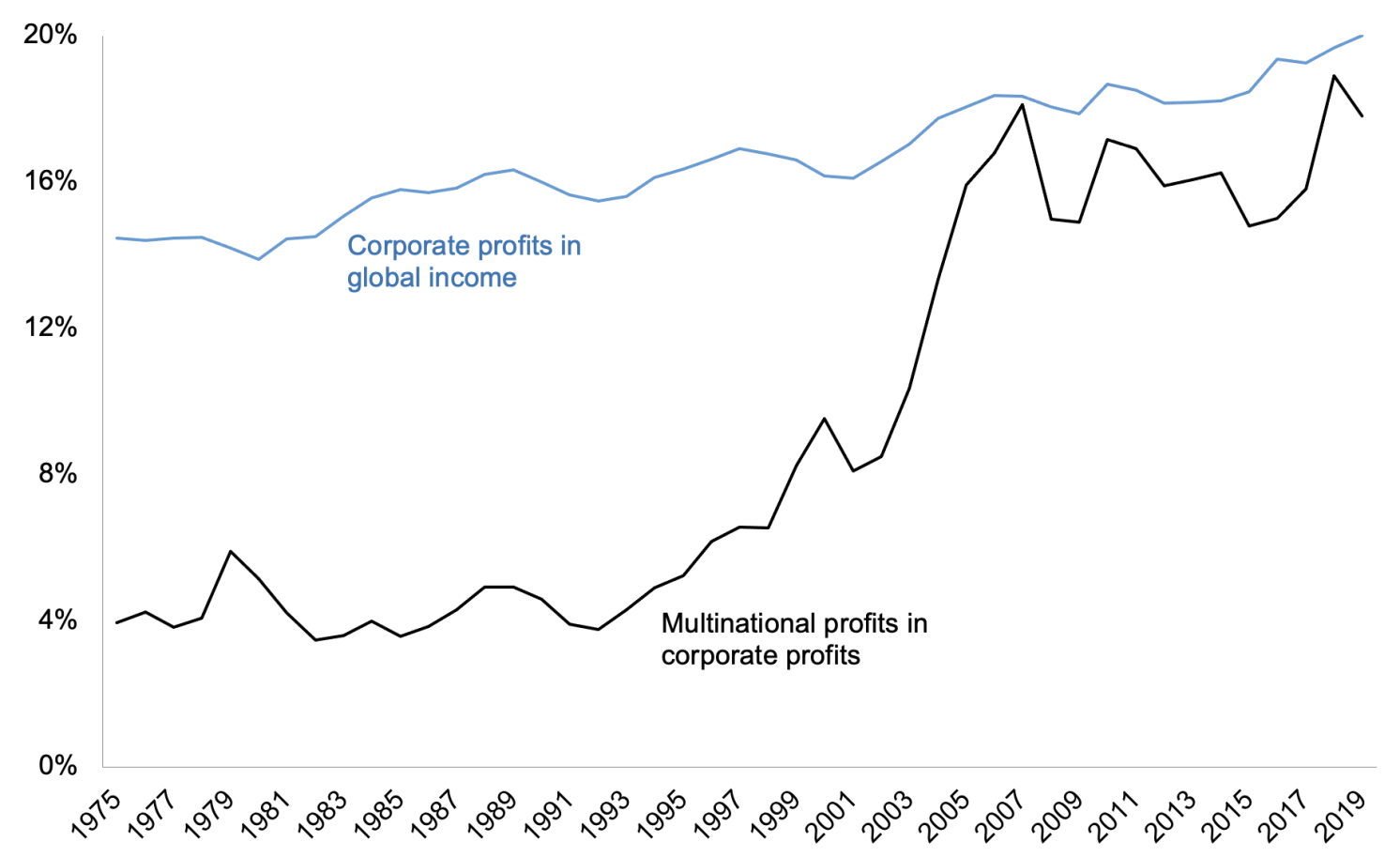

- Global corporate profits grew much faster than global income between 1975 and 2019. The share of profits in global income increased by a third over this period, from about 15% to close to 20%. This increase is due both to the rise of the share of global output originating from corporations (as opposed to, for example, non-corporate businesses) and the rise of the capital share of corporate output. The fast growth of corporate profits means that if the effective global corporate income tax rate had stayed constant, global corporate tax revenues (as a fraction of global income) should have increased by about one third since 1975. In reality, corporate tax collection has stagnated relative to global income – that is, the global effective corporate income tax rate has declined by about a third.

- There has been a large rise in multinational profits, defined as profits booked by corporations in a country other than their headquarters. The share of multinational profits in global profits has more than quadrupled since 1975, from about 4% to about 18%. This evolution reflects the rise of multinational firms, a well-known development but for which a global quantification was lacking so far. The rise has been particularly pronounced since the beginning of the 21st century. This evolution may explain why the issue of how to tax multinational firms has become more salient in the first two decades of the 21st century. When foreign profits accounted for only about 5% of global profits (as was the case from the 1970s through to the late 1990s), the tax revenues implications of properly taxing these profits were relatively small. With the rise of multinational profits, the revenue implications are significantly larger.

Figure 1 Corporate profits (% of income) and multinational profits (% of all profits)

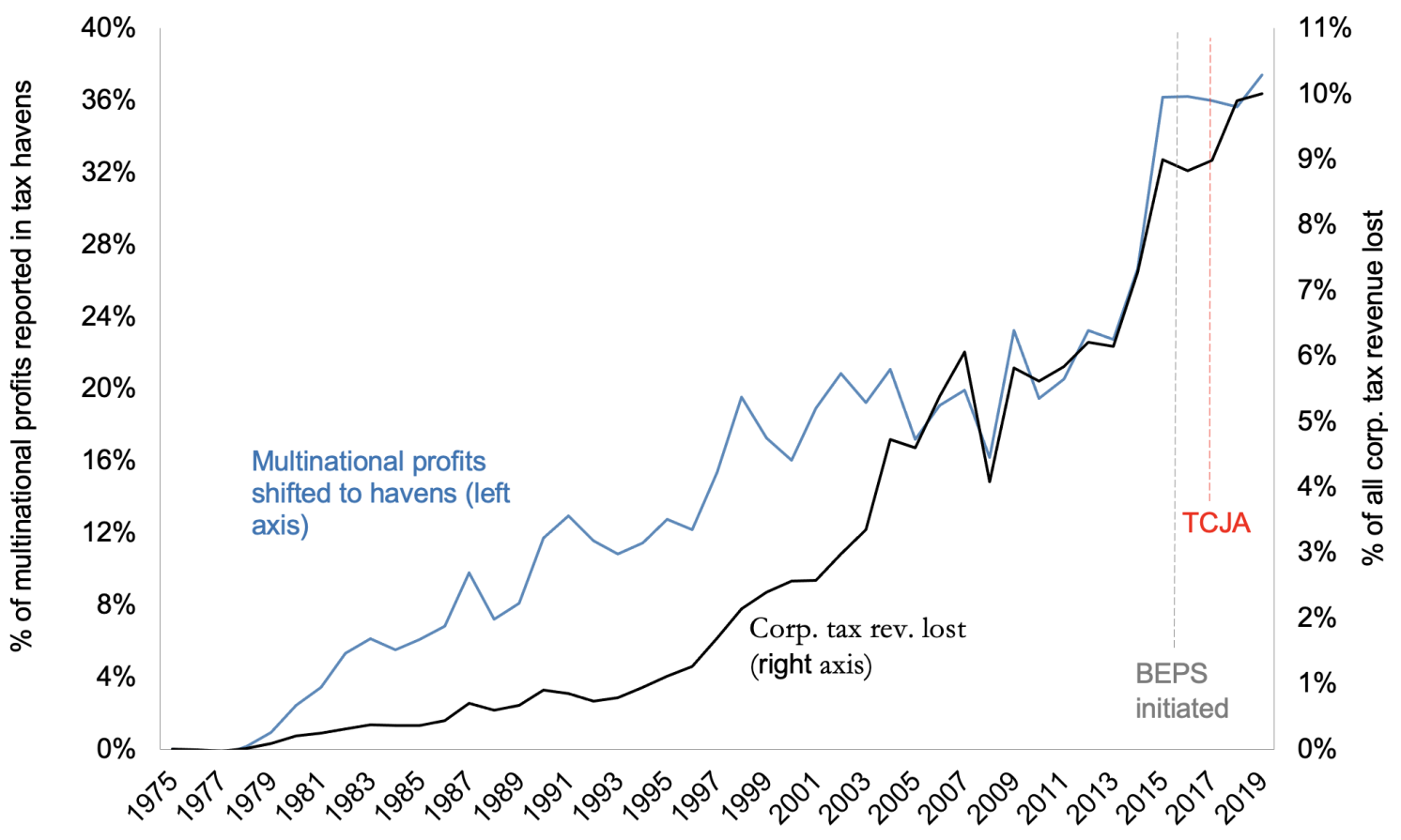

- There has been an upsurge in the fraction of multinational profits shifted to tax havens. By our estimates, this fraction has increased from less than 2% in the 1970s to 37% in 2019. Because multinational profits themselves have been rising much faster than global profits, the fraction of global profits (multinational and non-multinational) shifted to tax havens has risen from 0.1% to about 7%. Consistent with these findings, we estimate that the corporate tax lost from global profit shifting has increased from less than 0.1% of corporate tax revenues in the 1970s to 10% in 2019. The tax loss is slightly higher than the fraction of profits shifted to tax havens globally because the marginal rate on shifted profits is higher than the average rate.

Figure 2 Multinational profits in tax havens and corporate tax lost

- In 2019 – four years into the implementation of the BEPS process and two years after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act – there was no discernible decline in global profit shifting or in profit shifting by US multinationals (which, according to our estimates, account for about half of global profit shifting) relative to 2015. Of course, it is possible that absent BEPS and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, profit shifting would have kept increasing; we do not argue these initiatives had no effect. However, their effect seems, so far, to have been insufficient to lead to a reduction in the global amount of profit shifted offshore. This finding suggests that there remains scope for additional policy initiatives to significantly reduce global profit shifting.

Authors’ note: The views in this column are the authors’ and not necessarily those of the Danish Ministry of Finance. All of our research is available in the public database missingprofits.world. Here you can see the individual tax losses (or gains) of each country using our interactive map. You can also find the methodology description that was recently published in the Review of Economic Studies. We will continue to update our results as new data become available.

See original post for references

not one word about its the free trade stupid. the beefing up of the IRS recently i said will do little to stem tax avoidance. there will be some increase in revenues from the $600.00 rule, and that is where the lions share of the new agents will find work.

as long as we free trade, there will be no restoration of rule of law, and a civil society.

This video from 2013 is very good and uses real life examples such as Apple and Starbucks. For example, there is a royalty paid on every frappuchino sold in the world that ends up in the Netherlands due to a tax treaty or agreement where NV only applies a mere 2% tax on those profits.

Bankers, attorneys and accountants have constructed a labyrinth that rolls on while the world sleeps.

Fascinating!

How dirty our financial world really is! It makes me believe that the results of climate change is a proper end to our rotting civilization. Too bad that those who support and operate tax havens cannot be made to account for their illegal and greedy actions.

We are dirty too.

In the past decade I remember reading that 40% of all corporate profits were made by the banking sector- wonder where that number has gone and where all that cash is blowing up markets and evading taxation or is tax favored