To try to salvage its floundering central bank digital currency (CBDC), the eNaira, Nigeria’s Central Bank just launched an all-out assault on physical cash.

In October this year, the governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Godwin Emefiele, unveiled a plan to redesign and reissue high-value currency notes. It is ostensibly intended to mop up excess cash liquidity, stay ahead of counterfeiters and take greater control of Nigeria’s money in circulation, more than 85% of which is currently outside the vaults of the country’s banking system.

The central bank will begin issuing redesigned high value notes from mid-December and has given residents until the end of January to turn in their old notes. This week, a CBN circular titled “Naira Redesign Policy – Revised Cash Withdrawal” has offered more information about the demonetisation process. And it is, to put it mildly, troubling. From Bloomberg:

Nigeria’s central bank slashed the daily withdrawal limit from automatic teller machines in a bid to boost digital payments in Africa’s most-populous nation.

The Central Bank of Nigeria capped the maximum customer withdrawal at 20,000 naira ($44.97) a day, down from the previous limit of 150,000 naira, according to a circular sent to lenders on Tuesday. Weekly cash withdrawals from banks are restricted to 100,000 naira for individuals and 500,000 naira for corporations, and any amount above that limit will attract a fee of 5% and 10%, respectively, the central bank said.

The ultimate goal of these desperate measures is to breathe life into Nigeria’s floundering central bank digital currency, the eNaira.

As readers may recall, Nigeria was the first largish country in the world to launch a CBDC, which it did with the advice and assistance of the IMF. The roll out of the eNaira, in October 2021, put the West African country in the “global spotlight”, attracting the interest of “global stakeholders” such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, other central banks [which are working on their own CBDCs] and “the CBDC community,” the CBN noted in October this year.

But so far, the eNaira has been a complete dud, as I reported in July and November. The numbers speak for themselves.

The eNaira recorded just 700,000 transactions worth ₦8 billion ($18 million) in its first year. By August only 905,588 people had downloaded an eNaira wallet — a thoroughly underwhelming number in a country with an estimated population of 225 million people. Worse still, only 282,600 of those accounts, representing just over 0.1% of the population, were currently active. Meanwhile interest in cryptocurrencies has continued to rise despite a government ban barring financial institutions from enabling transactions in cryptocurrencies.

But as I warned in my previous post on this topic, the central bank is undeterred. In fact, with the world’s central banks and Bretton Woods institutions watching on, it is arguably more determined than ever to make its CBDC a success. To deepen its drive to “entrench a cashless economy” (its own words) and boost take-up of the eNaira, it is launching a demonetisation process not too dissimilar from the one India’s government unleashed in late 2016.

As of January 9, Nigerians will face an 87% reduction in the amount of cash they can withdraw from the bank on a daily basis before having to pay usurious fees. The central bank will also ban the cashing of checks above 50,000 naira over-the-counter and set a limit of 10 million naira on checks cleared through the banking system. Cash withdrawals from point-of-sale terminals, which are frequently used by Nigerians who don’t have a bank account, will be capped at 20,000 naira daily.

“Customers should be encouraged to use alternative channels—Internet banking, mobile banking apps, USSD, cards, POS, eNaira to conduct their banking transactions,” the central bank said on Tuesday.

This gives a whole new meaning to the term “financial repression.”

As Matt Stoller noted wryly in a Naked Capitalism post back in 2011, the term “financial repression” is invariably used to describe financial policies that rentiers hate, such as “preventing them from moving their capital anywhere in the world at a moment’s notice, stopping them from engaging in predatory lending and usury, directing investment to national priorities (like public investment, war, health care and education, a safety net, etc), and regulating banks so they don’t become casinos.”

In recent years it has mainly been used to describe explicit or implicit caps on interest rates, usually well below inflation or, in the case of Europe and Japan, even below zero, as a means of gradually liquidating bloated government debt. In this case it is savers who have been on the sharpest end of said repression.

Now, the CBN appears to have devised a whole new brand of financial repression (or oppression), one not aimed at rentiers or savers but at the entire population. The goal is not to gradually liquidate government debt but to coerce people into using less cash and begin adopting digital means of payment — preferably the central bank’s own digital currency. As with India’s demonetisation of late 2016, the consequences are likely to be disastrous on both a micro and macro level.

Like India, Nigeria is an economy that is predominantly cash based. According to the 2022 edition of the FIS Global Payments Report, physical cash accounted for 63% of point-of-sale (POS) transactions — compared to an average of 44% across the Middle East and Africa.

“Entrenching” a Cashless Economy

The CBN wants to change that. In its list of eight reasons for pursuing demonetisation, published in October, the central bank straight up admitted that the “redesign of the currency will help deepen our drive to entrench a cashless economy as it will be complemented by increased minting of our eNaira.”

Demonetisation may well break some public resistance toward the CNB’s eNaira but it will be at huge social and economic cost. As in India, that cost will be borne disproportionately by the poor and vulnerable. As even the Associated Press reports, analysts worry the initiative will “hurt” daily transactions that people and businesses make, particularly given that Nigeria’s digital payment systems, including the eNaira, are often unreliable:

“The policy is intended to cause discomfort, to move you from cash to cashless because they (the central bank) have said they want to make it uncomfortable and expensive for you to hold cash,” economic analyst Kalu Aja said. “That is a positive for the CBN (because) the more discomforting they are able to achieve, the more people can move.”

But the move could backfire, and in a big way. As Tunde Ajileye, a partner at Lagos–based SBM Intelligence firm, told AP, rather than use digital payment solutions, most people are likely to respond to this particular brand of financial repression by hoarding their money:

“It is not going to drive people to start to try doing electronic transactions. On the contrary, it is going to move people away from the financial institutions.”

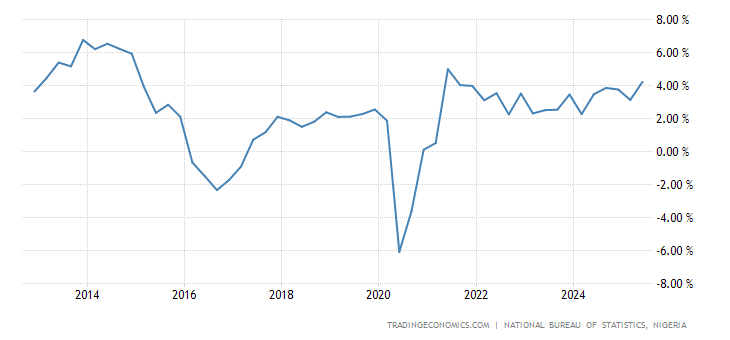

If so, that is likely to pile yet more pressure on an economy and currency that are already at breaking point. Economic growth in Nigeria is decelerating rapidly, as the following graph (courtesy of Trading Economics) attests.

Public debt has more than doubled in the past five years. Inflation is at a 16-year high while the naira is at its lowest point ever against the dollar, prompting the central bank to dig into its scarce foreign currency reserves to try to defend the currency. The crumbling naira together with rising interest rates in the US and beyond have also made it much harder for companies and the government to service their foreign-denominated debt.

It is against this backdrop that Nigeria’s central bank has decided to unleash a large economic shock upon the country. Many businesses may not survive the ensuing chaos, warned Senate Minority Leader Phillip Aduda (PDP, FCT) this week:

“Our commerce, I think, is not ready for this and our economy cannot take this shock. There is a need for us to speak about it because people are suffering and it is a very serious issue.”

A Case in Point

As readers may recall, India’s recent experiment with demonetisation achieved little of any substance while wreaking significant harm upon the economy. The immediate result of the sudden demonetisation was a liquidity crunch. Currency in circulation plummeted from 12.1% of India’s GDP in 2015-16, the year before demonetisation, to 8.7% in 2016-17, as the banking system struggled to re-inject new cash into the system. Economic growth spluttered as 85% of physical currency was pulled from circulation. Businesses went bust. Lives were ruined.

The shock to the system was huge. Given the suddenness and severity of India’s demonetisation, this was hardly surprising. In an article for Scrolled Arun Kumar, an assistant professor in Modern British Imperial, Colonial, and Post-Colonial History at Nottingham University, likens cash in the economy to blood supplying nutrients to all parts of the body:

Cash circulation enables transactions to occur, which help generate incomes. If 85% of the blood is taken out of the body and 5% replaced every week, the body will die. Similarly, when 85% of the currency in circulation was taken out and replaced little by little over about a year, the economy collapsed. If the currency had been restored within a few days, the damage would have been reversed.

The major component of the Indian economy is the unorganised sector, employing 94% of the workforce. It consists of the micro and small units which work with cash and not through formal banking. While the organised sector was hit due to shortage of demand as people lost incomes, the unorganised sector just could not function without cash.

As Kumar notes, the ostensibly intended outcomes of demonetisation — to root out unaccounted cash from the system, eliminate counterfeit currency and end the financing of terrorism — never really materialized. By the time the Reserve Bank of India made a final tally up how much of the demonetised currency ended up returning to banks, the figure was more than 99%.

What did happen was that large numbers of people, particularly in the middle and upper classes, began using digital payments, including the Unified Payments Interface, an instant real-time payment system developed by National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) and launched to the public in 2016. And that was probably the primary underlying goal behind India’s demonetisation campaign. Witness the Reserve Bank of India’s casual advice to the more than a billion people caught up in the ensuing chaos (emphasis my own):

While these efforts are afoot, [the] public are encouraged to switch over to alternative modes of payment, such as pre-paid cards, Rupay/Credit/Debit cards, mobile banking, internet banking. All those for whom banking accounts under Jan Dhan Yojana are opened and cards are issued are urged to put them to use. Such usage will alleviate the pressure on the physical currency and also enhance the experience of living in the digital world.

This prompted a seething response from Indian economist Jayati Ghosh:

Statements like this make one wonder whether the RBI is living only in the digital world. Surely the worthies in that institution have some idea of the conditions under which banking and money exchange occur for most Indians?… The facile assumption that moving to e-banking is just a matter of personal choice, which appears to underlie some of these arguments, is completely mistaken.

The same facile assumption is now being made by the Central Bank of Nigeria. All that’s needed, they think, is a little nudge in the right direction for people of all walks of lives and income levels to abandon cash and embrace digital payments. For fintech companies, most of them foreign, opportunities will abound. And whatever pain is caused along the way will be well worth the gain — at least for the central bankers, corrupt politicians, business and financial elite who will be largely, if not wholly, insulated from that pain.

As Jibrin Ibrahim, the Director of the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD), recently wrote in the online newspaper Premium Times, enterprising criminals and corrupt politicians will simply change their Naira into forex or cryptocurrencies, which will further depress the value of the local currency. Meanwhile, businesses will hit the wall, jobs will be lost and poverty will rise in an economy which is already close to the wall. And central banks around the world, almost all of whom are looking to develop their own CBDC, will watch on as the drama unfolds. Rest assured they will be taking notes.

More road kill created by Have-mores among the Have-less.

Seems like the cashless society has one huge weak point: absolute dependence on digital and electrical infrastructure. (And energy to operate them) Even without full digital payments I’ve been in situations where the gas station says “or card terminal network is down” and half the customers are simply screwed because they only use a debit card. I have to wonder if the designers of these systems are factoring these issues in or simply assuming they’ll always be too minor to be of serious concern? It’s not like some disgruntled person would ever disable an electrical substation!

Much less the right electrical substations that cause a cascading outage.

It might be counter intuitive, but Russia’s example of attacking critical electrical and other energy infrastructure seems to have been noticed elsewhere, and not just by State level actors.

With the reliance on the supply of electricity being a major node of “the System” today, said nodes become attractive targets for new fangled anarchists.

Substation in Clackamas OR (near Portland) is attacked….

https://www.kgw.com/article/news/investigations/pge-clackamas-substation-attack/283-08d66bab-30e9-4ca8-bb76-cde54ad46512

Good to see this variety of analyses on topics of Gitmo/de-dollarization/CBDC the last days (Gitmo in particular I think I last read a lot about back when Glenn Greenwald was on its beat, before Snowden).

One thing that goes unsaid here is that these efforts are primarily aimed at curbing gray economy and recovering tax revenue lost through these channels. In countries like Nigeria gray economy is a significant percentage of economic activity, for Nigeria estimates are 50-60%. It goes without saying that most of grey economic activity is conducted in cash.

So the government and the central bank have these wet dreams of significantly increasing their tax revenues by forcing these cash payments into official banking channels where they can be recorded and appropriately taxed. Inevitably, these efforts fail and the recovered tax revenue dwarfs the inflicted economic damage.

The people of Nigeria may soon be able to express an opinion about this hair-brained scheme. I see that they have their national elections scheduled for February next year – in about 11 weeks. But I do wonder how they will be able to work this system in practice. I mean, Nigeria is huge and is nearly as big as Texas but has some 225 million people living there. How many of them have reliable electricity and/or internet coverage for digital cash to work in the hinterlands? But it is easy to see why Nigeria was chosen as the next crash-test dummy (after India) as the United Nations rates it to be one of the most corrupt countries that there is. It’s gunna be a mess but hopefully short-lived.

So, in a few months, if I were to show up in Nigeria with a pocket full of $100 bills, no enterprising Nigerian would sell me anything because it’s cash?

This policy may have the unintended outcome of making cash more valuable.