By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

“A forest ecology is a delicate one. If the forest perishes, its fauna may go with it. The Athshean word for world is also the word for forest.” ― Ursula K. Le Guin, The Word for World Is Forest

It’s been awhile since I’ve perambulated through the biosphere, but after the news flow this week (and the week before (and the week before that …)) I felt that I needed a palate cleanser. Perhaps you feel the same way. Here is an American Chestnut tree:

(Photography photo by Dr. Garden, Shutterstock.) I don’t know if this American Chestnut competes with Wukchumni’s Redwoods, but it’s certainly a wonderful tree. American Abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher wrote in “History of the American Chestnut” (1874):

[The American Chestnut’s] boughs are arranged with express reference to ease in climbing. Nature was in a good mood when the chestnut-tree came forth. It is, when well grown, a stately tree, wide-spreading, and of great size. Even in the forest the chestnut is a noble tree. But one never sees its full development except when it has grown in the open fields. It then assumes immense proportions. Having a tendency when cut down to send up many shoots from the stump, old trees are often found with four or five trunks springing from the same root. In such cases, no other American tree covers so wide a space of ground. Not even the oak attains to greater size or longevity.

A chestnut-tree in full bloom is a fine sight. It blossoms about the first of July, in clusters of long, yellowish-white filaments, like a tuft of coarse wool-rolls.

In Henry Ward Beecher’s time, the American Chestnut was a dominant species. From the American Chestnut Foundation (ACF):

The American chestnut, Castanea dentata, once dominated portions of the eastern U.S. forests. Numbering nearly four billion, the tree was among the largest, tallest, and fastest-growing in these forests. Because it could grow so rapidly and attain huge sizes, the American chestnut was often an outstanding feature in both urban and rural landscapes.

Chestnut wood was rot-resistant, straight-grained, and suitable for furniture, fencing, and building materials. In Colonial times, chestnut was preferred for log cabin foundations, fence posts, flooring, and caskets. Later, railroad ties and both telephone and telegraph poles were made from chestnut, many of which are still in use today.

Its nut fed billions, from insects to birds and mammals, and was a significant contributor to rural agricultural economies. Hogs and cattle were fattened for market by silvopasturing them in chestnut-dominated forests. Nut-ripening and gathering nearly coincided with the holiday season, and late 19th century newspapers often featured articles about railroad cars overflowing with chestnuts to be sold fresh or roasted in major cities.

(Castanea dentata, not the genus Aesculus (the horse chestnut), let alone the water chestnut.) In fact, the American Chestnut was a keystone species:

American Chestnuts supported many, many other species, ranging from 56 moth species whose caterpillars ate Chestnut leaves, to countless species of birds which relished their nuts, to large mammals such as black bears which relied upon the nuts as a main source of nourishment before hibernation. Over 200 million acres of forests were dominated by this tree, Castanae dentata.

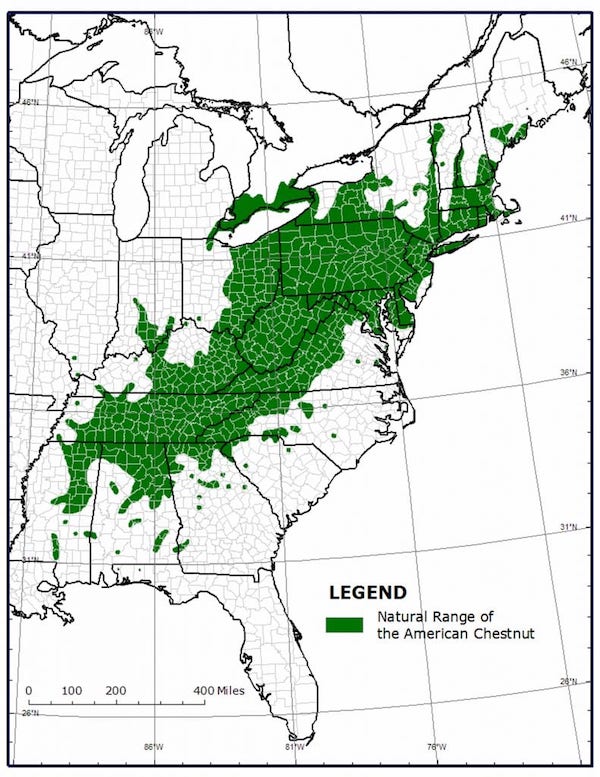

So ignore the haters. Here is a range map, again from the ACF:

So what happened? What killed four billion trees? In a word, blight:

The year was 1904; the place the Bronx Zoological Park in New York City; the beginning of perhaps the greatest single natural catastrophe in the annals of forest history—the discovery of chestnut blight. In less than 50 years more than 80 percent of the American chestnut trees in the eastern hardwood forests were dead; the rest were dying. A tree species that once occupied an estimated 25 percent of the eastern forest, encompassing 200 million acres of forest land, was gone.

Here’s how the fungus did its work:

Chestnut Blight, a fungal disease caused by Cryphonectria parasitica… invades the bark through any wound to the tree. It will kill the cambium (a layer of tissue in the bark) in a circle all the way around the tree. This kills all living cells above the infection (a process known as girdling).

As the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service puts it:

The American chestnut has been reduced from a dominant overstory tree to a small understory shrub

“Shrub,” because as Henry Ward Beecher writes, the American Chestnut “send up many shoots from the stump,” or, in this case, the portion of the tree below the girdling. From the USDA:

[The] American chestnut has managed to exist as short-lived stump and root sprouts, which will occasionally live long enough to flower and bear fruit.

A tragic fall, for such a noble, generous tree.

Attempts to revive the American Chestnut gathered steam in the late 1970s, when the American Chestnut Symposium was held. The American Chestnut Foundation was founded in 1983, when it began its breeding program:

Breeding for blight resistance was initiated around 1930, but those early programs were abandoned as hopeless in the early 1960s because they had been unable to combine the forest competitiveness of American chestnut with the chosen sources of blight resistance, oriental chestnut species. However, the early breeding programs did identify species with blight resistance and develop methods for making crosses, cultivating seedlings, and screening them for blight resistance. Charles Burnham (1981) first hypothesized that the blight resistance of Chinese chestnut, C. mollissima Blume, could be backcrossed into American chestnut. Backcrossing is the method of choice for introgressing a simply inherited trait into an otherwise acceptable cultivar.

(We might call this approach “classical,” as opposed to “genetic engineering,” which we’ll get to in a moment.) Trees don’t breed as rapidly as fruit flies or even garden peas, and so 2019 – 1983 = 36 years after the ACF began its program, we are close to a result. From the USDA, “What it Takes to Bring Back the Near Mythical American Chestnut Trees“:

The American Chestnut Foundation, a partner in the Forest Service’s effort to restore the tree, is close to being able to make a blight-resistant American chestnut available. Several national forests in [the Northern and Southern research] regions have hosted experimental American chestnut plantings to assist in the development of reintroduction strategies…. The end goal of this collaboration among scientists and foresters is that the integration of their research will yield a holistic set of tools for reintroducing an iconic and long-absent tree species to the region and once again restore the lost giant of the eastern forests.

With typical American extravagance, we have a second foundation, the American Chestnut Cooperators Foundation:

Breeding for blight resistance is currently pursued by two separate foundations: the American Chestnut Foundation (ACF) is developing advanced hybrids, building on the work of earlier breeders to improve tree form while enhancing resistance; the American Chestnut Cooperators’ Foundation (ACCF) is not using Oriental genes for blight resistance, but intercrossing among American chestnuts selected for native resistance to the blight.

In the 1970’s, ACCF located American Chestnut survivors of the original blight epidemic and grafted them into ACCF plots for blight resistance testing.

ACCF intercrossed these and other chestnuts which our tests identified and planted the progeny in all-American chestnut orchards (1982).

The ACCF is a volunteer (“cooperator”) organization of growers, with all the strengths and weaknesses that implies (and greatly in contrast to the ACF, whose Honorary Directors are Jimmy Carter and Norman Borlaug). From the ACCF’s current newsletter:

Projects and research by our founders began in the 60s, the roots of our heirloom program, built on the identification of existing blight-resistant all-American chestnut specimens and the examination of their blight-resistant qualities.

In 1985, the ACCF was organized and established to form the network of Cooperators dedicated to continuing pursuance of a research-based restoration program that serves this grand, native species….

With belief in the inherent strength of the American chestnut, the ACCF continues in its goal of restoring the American chestnut as a pure, significant species to its native range.

This is only accomplished by keeping a long-term perspective, continuing our work with patience and dedication, and through the continued efforts of our Cooperators.

(The ACCF’s website is purest 1990s, but includes a wealth of information on growing American Chestnuts.)

From the classical approach (whether based on Chinese crosses or All-American) we turn to genetic engineering, fruits (or nuts) of an effort at State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY ESF). From the Washington Post, “Gene editing could revive a nearly lost tree. Not everyone is on board.”:

The fungus infecting chestnut trees thrives by secreting a chemical called oxalic acid, which kills cells and allows the pathogen to feast on the dead tissue. But many other plants, including bananas, strawberries and wheat, avoid that fate by producing an enzyme called oxalate oxidase that breaks down the toxin.

By 2014, [SUNY’s Bill] Powell and [Chuck] Maynard successfully added the wheat gene to chestnuts and were growing infection-resistant trees. The pair dubbed one line Darling 58, in honor of Herb [Darling, who initiated their project].

At the orchard in Syracuse this June, a team working with Andy Newhouse, a biologist and assistant director of the restoration project, had dug hooks into their tiny trunks to intentionally infect them with the fungus.

The results were dramatic: On the tree carrying the disease-resistant gene, a gray, dime-size sore swelled up at the site of the quarter-inch incision — an infection from which the tree would recover. “The big public policy question is: Should we bring back forests with genetically modified chestnut trees?” said Edward Messina, director of the Office of Pesticide Programs at the Environmental Protection Agency, one of the agencies weighing approval. “That’s a pretty heavy question.” “This case sits right at the intersection of cutting-edge science and public policy considerations,” [EPA’s Edward] Messina said in a video call. Still the question remains, he added: “Just because we can do something, should we?”

Good questions, which have now entered the regulatory process:

The EPA is reviewing how the transgenic tree’s enzyme will interact with people and the woodland environment. The Food and Drug Administration is evaluating the nuts’ nutritional safety. And the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service is reviewing how the tree may affect insects and other plants.

I think the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) review is the important one. From the Hill:

[T]he U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has just released a draft environmental impact statement [(EIS)] and draft plant pest risk assessment that will allow the unrestricted planting [“unregulated status”] of blight-tolerant GE chestnut trees on public and private lands. If approved, the tree would be the first genetically engineered plant released with the purpose of spreading freely into the wild. Although the agency is recommending the tree’s release into wild forests, they are also requesting public input regarding their recent decision to do so. (You can submit comments here.)

45 days for public input over the holidays and ending December 27, seems less than ideal for such a big decision. Here are some of the concerns expressed in the previous round of public input:

APHIS solicited public comment for a period of 30 days ending September 7, 2021, as part of its scoping process to identify issues to address in the draft EIS. We received a total of 3,964 public comments. Issues most frequently cited in public comments on the notice concerning Darling 58 American chestnut included the following:

- Potential for gene flow to wild relatives;

- Potential to spread and become invasive;

- Potential non-target impacts, specifically to beneficial fungi, the microbiome, mycorrhizal networks, and the forest ecosystem;

- Potential impacts to wildlife, including pollinators, and threatened and endangered species; and

- Potential human health impacts from consuming nuts as well as potential allergies from pollen.

Of these, the first, “gene flow,” seems most important to me; if American Chestnut pollen is as promiscuous as alfalfa, that would be bad. The APHIS EIS argues that gene flow is both desirable and low risk. From “Environmental Impact Statements; Availability, etc.: State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry; Draft Plant Pest Risk Assessment for Determination of Nonregulated Status for Blight-Tolerant Darling 58 American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) Developed Using Genetic Engineering“:

American chestnut trees spread at an average rate of “no more than a few kilometers per century” (Paillet and Rutter 1989). It may take a century or more for blight tolerant chestnut trees to become dominant after the first pioneer trees become established in a given area. Slow natural colonization rates and frequent animal and pest pressure on seeds and seedlings (Clark et al. 2014), in addition with the limitations on pollen spread, suggest that chestnuts, regardless of type or transgene status, will not rapidly invade new areas (Cook and Forest 1978). Areas that are not intentionally planted with blight-tolerant chestnuts will likely remain without chestnuts for decades or longer (ESF 2019).

Under the Preferred Alternative [unregulated status], pollen mediated gene flow from Darling 58 American chestnut is possible. Darling 58 American chestnut is intended to be planted in proximity to native American chestnut trees with the hope that wild trees will flower and cross- pollinate to yield blight resistant seeds with the intention to increase the genetic diversity of the blight tolerant chestnuts. The transgenes from Darling 58 could also spread to related species through successful pollination with at least one transgenic parent.

There are two main objections to releasing the first genetically engineered plant “the purpose of spreading freely into the wild.” The first is the precautionary principle. From “That new chestnut? USDA plans to allow the release of GE trees into wild forest“:

Trees are complex organisms that interact with other living things over many growing seasons, if not centuries. For this reason, more research is needed if we are to fully understand the impact of GE chestnuts on larger forest ecosystems…. The supposition that genetically modified chestnut trees will behave in a specific and predictable way, based only on a decade of research, is premature, if not bad science.

Indeed, studies have shown that the genomic structure of transgenic plants can mutate as a result of gene insertion events and exhibit unexpected traits after reproducing. It is also possible that GE chestnuts, as they grow older and larger, will not be able to repel the blight, particularly if the OxO enzyme, produced by a wheat gene inserted into the DNA of the American chestnut, becomes less prevalent in mature trees. Scientists must be able to predict the future outcomes of their experiments and cannot reliably do so in the case of GE chestnuts.

However cliché it might be to state that those who do not learn the past are doomed to repeat it, in the case of the American chestnut this could very well be true. Chestnut restoration is an honorable undertaking, but the process should be done as carefully as possible, without harming the genomic heritage of this iconic tree. A wiser approach would be to adopt what the United Nations refers to as the “precautionary principle,” which restricts actions that can permanently harm a species or ecosystem, especially if there is no absolute certainty about their safety.

The second might be termed “the thin end of the wedge” or “the camel’s nose under the tent.” From In These Times:

The chestnut is very explicitly referred to in terms of its value for public relations and as a “test case.” Maud Hinchee, a former chief technology officer at tree biotechnology company ArborGen Inc. who had previously worked for Monsanto, stated, “We like to support projects that we think might not have commercial value but have huge value to society, like rescuing the chestnut. It allows the public to see the use of the technology and understand the benefits and risks in something they care about. Chestnuts are a noble cause.”

Scott Wallinger, a former vice president vice president of the paper corporation MeadWestvaco (now Westrock) said back in 2005, “This pathway [promoting the GE chestnut as forest restoration] can begin to provide the public with a much more personal sense of the value of forest biotechnology and receptivity to other aspects of genetic engineering.”

Even the American Chestnut Foundation said, “If SUNY ESF is successful in obtaining regulatory approval for its transgenic blight resistant American chestnut trees, then that would pave the way for broader use of transgenic trees in the landscape.”

I have to say that when I wandered into this post, I didn’t expect to find an explosive issue of genetic engineering, where a smallish USDA agency was charged with setting an enormous precedent. But here we are.

It would be completely in character, sadly, for grant-driven university researchers to avoid the precautionary principle. It would also be completely in character for Monsanto, et al., to make a “noble cause” into a mere public relations effort for an enormous increase in GMOs (though I suppose eating transgenic plants would be better than eating bugs, as the WEF would like us to do). We’ve just had a collective experience — some might say an experiment without informed consent — with how capital manipulates genetic material: mRNA. Regardless of what one thinks of vaccination or mandates, it’s undeniable that the side effects of mRNA were not predicted or even tracked. “Unregulated status” means that will be true for Darling 58; and darling 58 is intended to mix with heirloom genes. That doesn’t seem like a good idea to me. Much as I’d love to see the American Chestnut restored to its orginal range, I don’t see what the rush is. Hasty, as Treebeard would say. If you want to comment on the APHIS EIS, here again is the link.

My preferences lie with the ACCH and its cooperator approach. A Utopian vision indeed!

Food for everyone that could last 1000 years. Every October everything stopping for nut gathering and festivals. November milling & processing. Something so secure about that in a way I don’t think someone from 2020 could understand.

— BUILD SOIL; Plant Chestnuts! (@BuildSoil) November 26, 2022

Robust, however. Jackpot-ready.

Curious about a chestnut site (fenced and identified) I encountered while traveling some old roads “off the beaten track” in Phippsburg. Based on what I can recall of the signs, this appeared to be a small stand of native blight resistant chestnuts. I also recall a forester/forest ecologist friend telling me several years ago that there were small numbers of blight resistant chestnuts up through that part of the coast..

Given the range chestnuts covered, the genetic diversity would have been enormous. We’d expect there to be several different versions of blight resistance within that large pool. I expect this is what was used for one of the breeding programmes mentioned in the post.

Using the ones that survived is a traditional way to build breeding stock for resistant lines (roundup resistance was found in bacteria at the outflow from a glyphosate plant, for example).

There is speculation that the frenzy of clear cutting chestnut trees when the blight started to spread killed many of the trees that would have had some resistance. Not that there would have been that many anyways. Then add that the surviving trees, whatever their resistance, are scattered in isolated pockets; just finding all the pockets scattered throughout the East and then finding if they survived because the blight hasn’t arrived yet or the stand is made of blight resistant trees is difficult.

Any of the three different ways of getting and spreading blight resistance trees is multi lifetime effort. I have no problem understanding why some people just want to move. At least, I can still out my window and see Redwoods. Or just drive a bit and see a bunch of old, original forest. Having those trees die would likely kill my heart, corny as it sounds, it is the truth.

I completely understand – losing the trees you live with is an incredibly painful idea. I couldn’t imagine being without pockets of native bush and the omnipresent birds that it supports.

I’m not surprised to hear that people clearcut chestnuts to try and control the blight, eradicating potentially hardy trees. Agreed any reasonable approach to bring back a species like the american chestnut is many lifetimes work. Hard sell these days.

Here in the Sierra Foothills gold country there are mature healthy American Chestnut trees scattered around – they can be seen from some distance when in bloom, and the fragrance is intoxicating. e

Street view of a protected grove. There are numerous young trees from nuts along the road outside the fence.

The grove is dated 1916, so these are old trees. A couple have been removed recently; don’t know why, might be blight. There’s 6 ft thick trunk in there from one of these.

I assume they came over the mountains with the ’49ers and the blight hasn’t caught up with them yet. Nobody in the East seems to know about these out here. Maybe it’s a secret.

It has been quite sometime since I have been anywhere near the Sierras. I just might take a drive this summer to see those trees.

Are the Chestnut trees in Europe Chinese Chestnuts. They are very large and bear lots of nuts, The descriptions and flowering seem similar, a good tree. I am familliar with the Chestnut woods from the NY-PA area as well as Europe and they are also similar. What is the difference between the two? Could the European (Chinese?) Chestnuts thrive in the US?

They could and they do. Unfortunately, their nuts are bigger and less sweet than the nuts of the American chestnut are/were. They are also not the tall-growing timber-capable tree that the American chestnut is/ was/ could be again.

Also unfortunately, they can harbor the same blight which they themselves are immune to, and spread it back to any American chestnuts within the wind’s reach of them. Of course, it is that immunity which tempts people to wonder if it could be engineered into the American chestnut. And maybe it should be tried, under Level 4 biocontainment and exhaustive safety testing and without any private company involvement.

> Level 4 biocontainment

better still, perhaps do it in orbit, with artificial gravity to make the plants grow properly.

Which makes it seem that classical and neoclassical breeding is still the best way to go, especially in that we are already getting closer and closer.

And something else I just wonder . . . if the immune chestnuts produce a fungistatic or fungicidal chemical in their roots and ship it up into the trunk and branches, what if an American chestnut scion were grafted onto a Chinese/Japanese/European chestnut stock?

They would certainly take. But would an American trunk sitting on Euro/Sino/Japanese roots be blight tolerant or resistant or immune?

If it would, then at least we could revive grafted American chestnuts as an American nut orchard tree . . . producing the sweet little American nut even though not the huge American timber tree which the other chestnut roots could not support, I suspect.

The sweet chestnut, Castanea sativa, is the chestnut grown in Europe, although that isn’t to say Chinese chestnuts weren’t introduced at some point. The sweet chestnut is susceptible to the blight, but less-so than the American.

The Portland Arborist told me that a mature Chestnut is doing well over in Evergreen Cemetery in Portland. And check out tree hugging Castine. They label and number their Elm trees.

If any of those chestnuts are nutbearing female trees, and there are no armed guards preventing you from gathering some nuts, why not gather some nuts and plant them here and there? If the stand is guarded as well as fenced, perhaps the guards will sell you or give you some nuts.

As a big fan of GE in certain contexts, this is absolutely lunatic. They could be super careful about the release by first doing multiple deep sequencing runs to be entirely sure there were no off-target insertions or effects (common even with CRISPR-Cas9), but it would takes years to do the necessary functional analysis of the gene action within the chestnut.

It’s biology, it’s always more complicated than our models. There may be unexpected pleiotropic effects of the inserted gene itself, there might be unexpected gene interactions within the new host, and there may be the mentioned unexpected GxG(xE) interactions with the blight and other pathogens in the wild. None of those can be functionally tested within a short time frame when working with trees.

With an apparently successful backcross program already underway, it makes no sense at all to release a GE tree now to attempt to solve the same problem. The backcross programme being 36 years through, even assuming its as much as 8 years to do a hybridisation cycle from flower to tree to flower, it’s only 4 to 20 years to complete an adequate traditional introgression of resistance (proportion from donor parent = (1/2)^n+1 over n cycles). Cycle duration could be shorter using grafts onto suitable rootstock, I haven’t read up on the programme.

The forests are already gone, there’s no sudden crisis underway, we don’t need to rush trees out now when we’ll be ready with a safe version in a couple of decades at most.

Planted a hybrid blight resistant tree in 1980 in front of a modest frame home in Royal Oak, MI.

Last time I checked on Zillow, it’s about 40′ tall.

Norman Borlaug’s ‘green revolution’ procedures have met with savage criticism over the years. I tend to agree.

If nobody else posts about “The Overstory,” here it is. The American Chestnut figures large in what I consider a beautifully written novel.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/40180098-the-overstory

+1 on that — anyone interested in trees and our environment should check out The Overstory, great book.

On a related matter, I have 50 hybrid hazelnut bushes in my front yard. They were bred at Badgersett Research farm in Minnesota. I’m uncertain whether Badgersett is currently a viable concern.

These hazelnut bushes are crosses between Asian, European, and American hazelnut plants. They are bushes (like the American hazelnut), not “trees” like the European strains, and they’re supposedly Eastern Hazelnut blight immune. Not resistant, but immune.

In my stand of 50 bushes, there are as many “cultivars” (genetically distinct plants) as there are bushes. They’re all different. The genetics of these bushes are anything but stable; the genes from the three parent stocks can inter-breed, but they’re very, very different. The combinatorial genetic range of these bushes is immense. It’ll take a good long while before the genetics “settle down” and produce bushes that look, act, and operate the same. Generations, at least.

I bought and planted them with the express purpose of letting nature exert selection pressure on them, and letting the natural breeding, propagation, predation (deer, mice, etc.) and failure forces guide the evolution of those bushes. My theory was that Nature would evolve a set of cultivars that actually fitted into my local environment.

I’ll take many decades before I have any idea whether this set of bushes will survive. For now, they feed squirrels, birds and deer. I get nothing from this stand of bushes; they produce plenty, but everyone else gets there before I do. No nuts for me!

I’ve been a fan of the American Chestnut tree’s revival for many decades; I tuned in a while back. But I had trouble starting the chestnuts, and conversely no trouble at all starting and defending the hazels.

I am a rank amateur at this. I tremble to think what people like Greg (above) might think of what I did. Maybe it was reckless; many unfortunate things have happened at the hands of ignorance and misdirected hope. “The road to Hell is paved with good intentions”.

I surely wish that I did right, and that what I did will help re-introduce the hazelnut here in the mid-Atlantic East, where I happen to live. The bushes are surely feeding a lot of animals, and a lot of birds; the bushes are host to Brown Thrashers (among others), which nest in bushes, and are a declining species where I live. Surely there is some benefit, but I’m very interested to hear what people with much more genetics background than I have will say.

Thanks for any input; it’d be most welcome.

====

Lambert – thanks for raising this topic. I have been long (decades) interested in the re-introduction of the American Chestnut. Next edition of the subject, I hope you’ll relate the Passenger Pigeon’s fate to that of the Chestnut. I’ve heard rumors that the Chestnut’s demise was more relevant to the pigeon’s demise than (even) over-hunting.

Badgersett is still, I believe, alive and well and at least some of it’s output is available through The Experimental Farm Network;

https://store.experimentalfarmnetwork.org/collections/perennial-vegetables

who do their own share of excellent breeding work.

I am typing from an extremely limited functionality hotel computer, so I can’t even find links to offer. My memory is that the Passenger Pigeon was strip mined into near non-existence by the 1890’s. The last great nesting colony attempt was called the Petoskey nesting as I remember and was attempted in 1890-something somewhere in Wisconsin. As soon as it was discovered, its finders sent word by telegraph in every direction calling on all hunters, market gunners, etc. to come and kill them all. Which they did.

This happened several decades before the 1910’s and 1920’s wipeout of the chestnut. And a few American chestnuts still live on.

There is nothing GMO about planting different sorts of hazelnuts and letting them cross pollinate each other to produce hybrid offspring. This is a method used in classical and/or neoclassical plant breeding. I am no professional, but I see no possible harm in these hazelnuts.

The crossing and backcrossing and back backcrossing and back back backcrossing of these nearly American chestnuts to get a nearly American chestnut which can resist or tolerate the blight for a reasonable lifespan is the same sort of classical breeding done in a modern way.

Old stump root systems keep sending up new little trunks. They keep trying and trying. They should be preserved on the chance that their roots harbor the same sort of legacy mycorrhizae who lived on the roots of the pre-blight chestnuts, since some of these are living pre-blight stump-root systems. If a nearly American chestnut reaches the point of being release-ready, it may want to have the good old-time mycorrhizae living on its roots.

3 years ago at a conference I heard Akiva Silver, author of Trees Of Power ( Ten Tree Allies) give a talk about staple foods from chestnuts, hickories and hazelnuts. Somewhere in that lecture he spoke about Korean Chestnuts which are generally considered a small blight-immune tree species. But he claimed that several 80 foot tall specimens were known to exist in the forests of North Korea. I don’t know if that is true, but I know he made that claim. If it is true, then hybridizing those 80 foot tall Korean chestnuts and American chestnuts might yield a hybrid able to grow nuts midway between the two species in size, on trees midway between the two species’ height. Since the America chestnut tree could sometimes reach 150 feet high, a North Koreamerican hybrid ( or a North Amerikorean hybrid if one prefers) should on average be able to reach 125 feet high just by the arithmetic of averaging. One hopes such a hybrid may someday be made and grown just to see.

Many years ago I was visiting family in Saratoga Springs, NY. At Cafe Lena I met someone who was introduced as an amateur story-teller among other things who claimed Abenaki ancestry and who claimed to own land somewhat south of town. He claimed to have a few 80 foot tall American chestnut trees on his land which he said produced large numbers of nuts and which he claimed to believe to be naturally blight-tolerant or immune based on their unblighted size. That’s a very faint and slender lead to go on but there it is.

Blight immunity GMO’d in from Chinese or Japanese or European or Korean chestnut might be one thing, but a “fungus immunity gene” engineered in from wheat seems a gap too wide to predict from.

I believe Mark Shephard sells either large numbers of pure American chestnut seedlings or pure American chestnut seeds or maybe both on the theory that if many people plant them in many places, some might just happen to be resistant enough to survive.

The climate is changing and will change much more rapidly than trees and other slow growing organisms can adapt through normal processes of evolution. Such adaptation as does take place will probably occur at time scales too slow to be meaningful for human adaptions. I believe there is no guarantee that natural adaptations will be any more beneficial to humans or the present ecologies of life than runaway Franken-GSM adaptations. Humankind will be faced with adapting to wide ranges of dead and dying forests or making a best effort to help selected plant and animal species adapt. I believe GSM processes remain crude and high risk. More than a little basic science must be supported by government research grants — NOT research contracts tendered under the conditions of Bayh–Dole Act intellectual property rights. While GSM is risky, such a risky yet crucial venture should not be left to the tender mercies of the Neoliberal Market or the present system of academic profiteering and careerism.

After Chestnut Trees — what about Dutch Elms?

I’m an outdoorsman, and spend a lot of time out in the woods. I am mostly fine with a genetically modified chestnut being released onto the landscape.

That range displayed in the map is not even close to the range of a plant like autumn olive or stilt grass. I’d much rather see chestnuts trying to get a toe hold than any more noxious invasives.

I hope the genetically modified tree gets deregulated for a number of reasons. First, the tree has been more or less absent from the forest for almost a century. We are quite lucky that American Chestnut is a prolific stump sprouter. If it had been an evergreen tree it would have gone extinct. While there are likely millions of AC small trees and sprouts in the Eastern US, they will continue to be gradually lost over time due to disturbances, land clearing, and deer browsing. I was seen several AC sprouts get killed by deer browsing.

Second, there have been many breeding efforts by different groups starting in the 1920s and none of them have been successful so far. The current effort by TACF has not been succcessful yet. They recently discovered that there are many more genes involved in blight resistance than was originally hypothesized 35 years ago by Burnham. He thought there were only 2 or 3 genes involved in blight resistance. It has been recently discovered that there are genes in 9 different chromosomes involved in blight resistance. It will be close to impossible to create a mostly American tree with blight resistance.

Third, so many of our native trees are at risk due to introduced insects and diseases. Beech, ash, oak, maple, walnut, butternut, hemlock, and white pine have all been affected to some extent by invasive pests. The loss of these other trees is terrible. By bringing back AC there will be hope that science and technology can solve problems created by human errors in the past. The reduction of these other species also creates a void in the forest that AC could fill. I just finished hiking parts of the AT in Shenandoah NP and there are lots of places where oak and ash are dying or dead. These areas can be replanted with a truly resistant AC.

Fourth, the scientist at SUNY ESF have completed dozens of studies over the last decade on how the transgenic tree would affect the forest ecosystem. The have studied the nuts and found no problems there. They studied leaf decomposition in aquatic ecosystems and found no problems there. They have conducted a bunch of additional studies and found no problems. Please see papers here: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=XUi4yYEAAAAJ&view_op=list_works&sortby=pubdate

As for transfer of the oxalate oxidase gene to close relatives, there hardly are any chestnut relatives in the US. There are only three species in the US: American chestnut, Allegheny chinkapin and ozark chinkapin.

If the genetically engineered tree is not deregulated then we will be left with a lot of useless hybrids that aren’t competitive in the terms of height growth with other native forest trees. A hybrid or pure Chinese chestnut can’t fully reach the canopy on many sites and are outcompeted by yellow poplar and red oak along with other tall trees. These hybrids are not very resistant to the blight either. Trust me, I have planted dozens of the “resistant” AC trees only to watch them die of chestnut blight a few years later.

One quibble – 9 loci doesn’t mean you can’t use traditional(ish) methods.

After you’ve nailed down the loci involved in the resistance, there’s no reason you can’t use a marker-assisted backcross to get all the loci into a single line. It takes a larger number of crosses the more loci you want to combine, but you can do things like recrossing hybrids to recombine until you get them all together, before going through backcrosses using markers to make sure you don’t lose the loci.

It’s hard work, which is why people want to jump to GE, and ignore the risks inherent in our current methods of GE. As I mentioned above, even CRISPR-Cas9 has proven to have an unreasonably high number of off-target effects, nevermind the old agrobacterium approaches.

Thanks Greg. I agree with Lambert’s “camel’s nose under the tent” comment re: introducing GE ACs into the wild because it sets a troubling precedent that may not be reversible. Hence, the emphasis on “precaution.”

From the Global Justice Ecology Project:

Biotechnology For Forest Health? The Test Case Of The Genetically Engineered American Chestnut is a detailed forty-eight page report that focuses on the controversial effort to use the American Chestnut tree, which has suffered tremendous population loss due to blight and over-logging, as a test case to allow the unregulated planting of it and other GE forest trees in wild forests and plantations.

The white paper produced by the Campaign to STOP Genetically Engineered Trees, Global Justice Ecology Project (GJEP) and Biofuelwatch describes the science and risks associated with plans to release genetically engineered American chestnut trees into forests. If approved it would be the first GMO plant allowed to grow freely in the wild.[NOTE: my emphasis.]

As set out by the report’s main authors, Dr. Rachel Smolker of Biofuelwatch and Anne Petermann of GJEP in the report’s executive summary, “The genetically engineered American chestnut is highly unlikely to enable successful restoration of American chestnut to our forests and therefore it is not worth taking the risks. The real reason this genetically engineered American chestnut is being promoted so strongly is as a public relations tool to gain support for the use of biotechnology on forest trees.”

Read the two page Executive Summary here.

GJEP pushes back on the SUNY-ESF report.

“The GE American chestnut would have unknown and potentially irreversible impacts on forest ecosystems, songbirds, wildlife, soils, and human health. This is not restoration, but a dangerous experiment with our forests.

Industry is using the GE chestnut to undermine historic widespread opposition to GE trees by claiming it will be used for “conservation.” They anticipate that approval of the GE American chestnut will open the floodgates to profitable plantations of genetically engineered trees like poplar, pine and eucalyptus–GE plantations that would further threaten forests.“

Just scanning the first fifteen pages of the report you referenced says volumes about the initiative to bring back the Chestnut tree. Just the list of Corporate Green Pretenders involved paints the project described in this post a very sickly false “Green”, like a bastard child of the “Green New Deal”. Its appearance as the funding for the IRA appears on the horizon adds to my suspicions.

However, I am not convinced that genetic modification of plants, especially trees, is a bad idea in and of itself. I hope I am wrong, but I believe that trees and large mammals can adapt to change much more slowly than bacteria, fungi, and other plants and creatures whose generations are short and whose populations are large. Climate Chaos is only one of many factors rapidly impacting the environment and life on Earth and Climate Chaos alone is bringing deadly change as and perhaps more quickly than any other extinction event in the Earth’s long history. I have every confidence that Nature will adapt the Earth and its life to the changes Humankind has unleashed. Nature adapts slowly. The direction of adaptation it might choose is impartial to impacts on human life or on the flora and fauna as we know them now.

I do not believe Humankind has a choice whether to attempt the genetic modification of selected plants and animals in an effort to nudge the direction of change in a direction more favorable to Humankind. It is not as if Humankind has not played with plant and animal genetics for the last tens of thousands of years. Now we have much more powerful tools to work with. I believe along with greater power, our new tools bring greater mystery, risks and scope than anything available before now. I strongly agree with your opposition to the present programs to genetically modify the Chestnut Tree. The GMO Chestnut tree definitely appears to be a carefully selected Trojan Horse promoted and financed by many of the very unhuman actors that have worked so hard to wreck destruction on the Earth. Humankind still knows too little about how their powerful tools work their magic. Much basic research and discovery must precede any wide-scale efforts to do anything like attempt to change the forests. I believe deep Knowledge of genetics and the mechanics of genetic change could be discovered — if only some semblance of Science were reborn. For the survival of Humankind Science must be freed and reborn from its present state of subjugation. [I am very doubtful that the forces of Climate Change can be so well understood. Hence I remain strongly opposed to Geoengineering.] We cannot Science our way out of all the problems we face, but Science remains a powerful tool we should not too lightly shun.

But science has become the whimpering chattel of Neoliberal Corporate entities pushing wanton efforts to find new sources of profit no matter their costs to others.

I have seen the many stands of dead pine trees near where I live. But I did not realize how many other kinds of trees are similarly threatened as Climate Chaos progresses. We may too soon be living in a land of ghost forests.

How can you be so confident that the end product will actually be an American chestnut, and not some lab facsimile that is only superficially similar? How will the lab-created specimen approach even the limited genetic diversity of the remaining American stock?

GE may have appropriate applications but it isn’t the panacea that it is portrayed as. It’s mostly a tool to concentrate control of biological resources into fewer and more powerful hands. It also threatens biological diversity, as with the Mexican maize genome.

Chestnuts from what I understand became a predominant species by 1900 because they were the most successful new growth following the original, virgin eastern hardwood forests. In very short order virgin forests were destroyed throughout lands settled by Europeans for use as building material or removed for agriculture. I do not believe that 500 years ago they would have been so dominant, but could be wrong. We have the same situation in the Adirondacks; there were enormous stands of virgin white pine, hemlock and spruce. Once logged (pretty much gone by 1900) the hardwoods took their place. Beech became a very common successor which is also affected by a blight. Large trees succumb, but huge thickets of small growth erupt from the roots that get wiped out by blight. Rinse, repeat.

And don’t get me started on my acres of dead ash, killed by the emerald ash borer.

Agreed: given historical successional dynamics which are not replicable in present circumstances, the range that was their past range will not be their future range, especially keeping climate shifts in mind. And further: chestnuts are mammal-vectored, hence will spread fairly slowly absent massive human reintroductory efforts. Which is to say, we will not rapidly re-engineer Arcadia, but it’s a sweet vision. But how to make them invasive? Now that’s a strategy.

Thanks Lambert

Crazy timing on Chestnut News.

Got notice last week that On Monday December 5 TACF is planting hundreds of ACs and Hemlocks just outside of Morganton NC on the Linville River Nursery. They were calling for volunteers.

So limited planting is proceeding w/o USFS/USDA approval.

I had not heard of the ACCF despite knowing a bit about The ACF. I like their approach of seeking survivors with natural immunity instead of back breeding to immunity.

There are blight survivors for sure— my two Mother Trees on the southern homestead are only between 35 and 65 years(counting rings on trim cuts) and have given me more than a dozen more saplings now 2-5” in diameter throughout my woodlot. But there are some monsters all over the Century Farms just south of Kings Mtn. NMP. Turns out the Neutral Ground between the Broad R and Catawba R —which separated the Cherokee from the Catawba—had historical notoriety for its Chestnut canopy —so separated from the Blue Ridge Foothills. See the map at the ‘Carolina Step’.

On the old home place in Ohio’s Mahoning Valley I now have several ACs growing, and fruiting, from unknown origin. The old timers there claimed that the homestead next to us had both the barn and Plank House built of Chestnut milled out of the homestead woodlot. In the 80s, selling your barn for the Salvage Wood was a thing that complimented the rise of the rust belt in that part of Ohio.

They are beautiful trees, imo, especially the pasture trees that have full crowns from full sun.

Deer will jump the chain link to get the Mast from our biggest sitting just inside.

The Burrs are a messy pain though, even the dogs pick their paths carefully in October.

Thanks.

Longfellow: The Village Blacksmith

https://poets.org/poem/village-blacksmith

Second verse from the song, I’ll Be Seeing You, written 1938:

In that small cafe,

The park across the way,

The children’s carousel,

The chestnut trees the wishing well.

I did not have time to add an Appendix of links on how to grow your own. A few starting points:

FedCo sells American Chestnuts; good description here.

Excellent, detailed, step-by-step post, for example:

Tomatoes were my gateway plant; they are easy and quick (and tasty). Only after about five years did I realize I wanted/needed trees. But if I had planted my filbert trees when I started planting tomatoes I would have had edible nuts, instead of a realization.

So think about trees first. Not as an afterthought. (I also ran out of time to investigate American Chestnuts and edible forests….)

Just a quick comment that a chestnut industry is already being rebuilt in the states. In Michigan, the Chestnut growers co-op is providing a valuable service to recreate the Chestnut food industry https://chestnutgrowersinc.com/

I looked into the program about 5 years ago and was quite impressed with the work that they do, assisting farmers to transition to chestnut growing and providing a ready market for sale.

With an eye towards the precautionary principle, I do not see any strong enough reason to introduce GE American chestnuts. Non GE blight resistant trees are closer to reality every year, a viable hybrid Chestnut food industry is maturing steadily. To me, I take this as strong evidence supporting the remarks on the true intentions of the American Chestnut engineering programs, to provide a feel good story for bioengineering companies to take advantage of.

If it was truly about the plants, why wouldn’t they support breeding efforts and efforts to scale up the hybrid food industry?

I own about a 50 acre wood lot in upstate NY on the PA border. I discovered a Chestnut tree big enough to bear chestnuts. Wild chestnuts look like big beech nuts. I haven’t been in that part of the woods for several years. I hope it is surviving but don’t know if it is.This tree was relatively small but still produced nuts. Trees are susceptible to all kinds of threats. Disease and insects responsible for destroying many trees.Often these threats are selective destroying one variety of trees.

A few years back I visited a chestnut orchard in Peterborough, NH at the Shieling Forest. This article tells a bit about the orchard.

https://www.sentinelsource.com/elf/outside_my_door/reviving-the-american-chestnut-tree/article_027718bc-65b2-11e8-9e1d-e3c12e398ed8.html

From the article:

“A New Hampshire chestnut orchard can be found in Peterborough at the Shieling Forest where 325 trees were planted. Those trees were inoculated with two strains of chestnut blight in July 2017. It will take a couple years to know if the trees are resistant enough to survive.”

This occurred to me spontaneously: I wonder if the tree could be sufficiently revived in forested areas it would take some of the pressure off deer currently ravaging suburban gardens. So I looked it up on google and found that chestnuts are indeed the preferred food of deer and “should be part of everyone’s deer management program”. The link is talking about attracting deer, but what about attracting them away from residential areas and back to the forest? Of course we would have to revive/create/expand our wildlife corridors.

The article seems to say that it is the nuts themselves which attract the deer. And Chinese/European/Japanese chestnuts seem to be equally attractive to the deer of our own time. While planting chestnuts as deer magnets in chestnut season would not relieve deer pressure on suburbia outside of chestnut season, it would gather many of them on one place during chestnut season, where they could be rounded up and sustainably harvested and processed for meat like the Indian Nations did in their day. That would both feed some people and restrain deer pressure on yards, gardens and farms.

We had our Green Ash cut down last week, it was featured on Water Cooler about 6 months ago, riddled with Emerald Ash Borer trails.