Yves here. Today we turn to an important element of the nature v. nurture question, that of education, and how that plays into inequality.

A cross-post yesterday on the promotion of “race science” provided a revealing set of comments, not necessarily in a good way. I should have posted this section from an article in Sapiens as a prophylactic:

A friend of mine with Central American, Southern European, and West African ancestry is lactose intolerant. Drinking milk products upsets her stomach, and so she avoids them. About a decade ago, because of her low dairy intake, she feared that she might not be getting enough calcium, so she asked her doctor for a bone density test. He responded that she didn’t need one because “blacks do not get osteoporosis.”

My friend is not alone. The view that black people don’t need a bone density test is a longstanding and common myth. A 2006 study in North Carolina found that out of 531 African American and Euro-American women screened for bone mineral density, only 15 percent were African American women—despite the fact that African American women made up almost half of that clinical population. A health fair in Albany, New York, in 2000, turned into a ruckus when black women were refused free osteoporosis screening. The situation hasn’t changed much in more recent years.

Meanwhile, FRAX, a widely used calculator that estimates one’s risk of osteoporotic fractures, is based on bone density combined with age, sex, and, yes, “race.” Race, even though it is never defined or demarcated, is baked into the fracture risk algorithms.

Let’s break down the problem.

First, presumably based on appearances, doctors placed my friend and others into a socially defined race box called “black,” which is a tenuous way to classify anyone.

Race is a highly flexible way in which societies lump people into groups based on appearance that is assumed to be indicative of deeper biological or cultural connections. As a cultural category, the definitions and descriptions of races vary. “Color” lines based on skin tone can shift, which makes sense, but the categories are problematic for making any sort of scientific pronouncements.

Second, these medical professionals assumed that there was a firm genetic basis behind this racial classification, which there isn’t.

Third, they assumed that this purported racially defined genetic difference would protect these women from osteoporosis and fractures.

Some studies suggest that African American women—meaning women whose ancestry ties back to Africa—may indeed reach greater bone density than other women, which could be protective against osteoporosis. But that does not mean “being black”—that is, possessing an outward appearance that is socially defined as “black”—prevents someone from getting osteoporosis or bone fractures. Indeed, this same research also reports that African American women are more likely to die after a hip fracture. The link between osteoporosis risk and certain racial populations may be due to lived differences such as nutrition and activity levels, both of which affect bone density.

But more important: Geographic ancestry is not the same thing as race. African ancestry, for instance, does not tidily map onto being “black” (or vice versa). In fact, a 2016 study found wide variation in osteoporosis risk among women living in different regions within Africa. Their genetic risks have nothing to do with their socially defined race.

When medical professionals or researchers look for a genetic correlate to “race,” they are falling into a trap: They assume that geographic ancestry, which does indeed matter to genetics, can be conflated with race, which does not. Sure, different human populations living in distinct places may statistically have different genetic traits—such as sickle cell trait (discussed below)—but such variation is about local populations (people in a specific region), not race.

This post describes an important aspect of the nature versus nurture question, which is the role of formal education and the advantage the more affluent have in paying for their children to have more and better quality instruction.

By Matthias Doepke, Professor of Economics London School of Economics and Political Science, Jan Stuhler, Associate Professor Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, and Jo Blanden, Professor of Economics University of Surrey. Originally published at VoxEU

In modern economies, people’s livelihoods are based in large part on skills acquired through education. Unequal education therefore drives both inequality in the labour market and low social mobility across generations. This column reviews the evidence on how family background shapes differences in educational outcomes, mechanisms, and the potential role of policy. The implications of educational inequality are pertinent given the COVID-19 pandemic, in which widespread school closures have created new challenges to learning that put children from low-income families at a particular disadvantage.

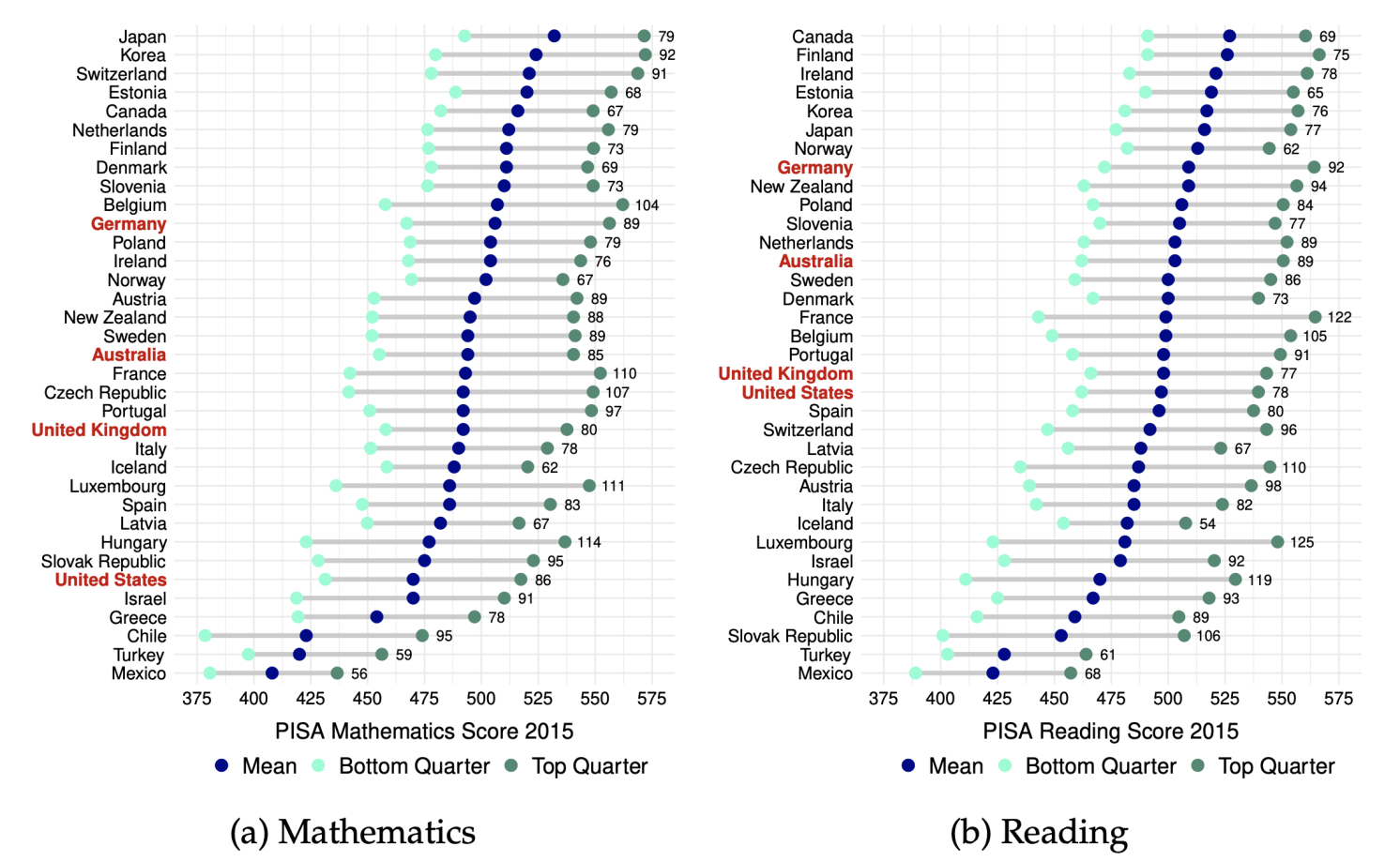

Educational inequality is vast. Figure 1 compares average scores from the 2015 wave of the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) by country to the average scores for children from families in the top and bottom quarter of a measure of socioeconomic status. The socioeconomic gap in test scores amounts to almost a standard deviation. Even in the best-performing countries, the scores of students from disadvantaged backgrounds are below the OECD average.

Figure 1 PISA scores by country and socioeconomic background

Notes: The figure reports the mean PISA 2015 results for OECD countries and the mean scores in the top and bottom quarters of the PISA index of economic, social, and cultural status (ESCS). The numbers refer to the gap between the mean scores in the top and bottom quarters for each country. Source: OECD (2016).

These large socioeconomic gaps imply that educational inequality is a key element in the reproduction of inequality from one generation to the next. Economic inequality contributes to large gaps in the investments that parents from different parts of the income distribution make in their children’s education. Given high economic returns to education, educational inequality in turn implies both economic inequality and low social mobility.

Indeed, the ‘Great Gatsby Curve’ shows that countries with more income inequality also tend to have lower income mobility (Corak 2013, Blanden 2013), and a similar association is observed across regions within country (Chetty et al. 2014, Güell et al. 2018). This pattern is also reason to be concerned about future social mobility. Income inequality has been rising in many countries, and the Great Gatsby Curve suggests that this might result in lower social mobility and in an economically divided society in the future. But how likely is such an outcome of ever-lower social mobility?

The Educational Great Gatsby Curve

To get an answer, one should first consider the link from economic to educational inequality. Conceptually, there are good reasons to expect economic inequality to increase educational inequality. By raising the stakes, it spurs well-off parents to double down on investing money and time in their children, while those of lesser means may not be able to keep up.

Indeed, there is evidence for rising socio-economic gaps in parental investments in recent decades (Doepke and Zilibotti 2019). In the US, upper-middle-class parents have increased their time and money investments in children compared to less fortunate families. However, even though gaps in inputs have risen, the evidence for gaps in outputs is less clear. For example, socioeconomic gaps in tests scores in the US appear to have been broadly stable over the past few decades (Hanushek et al. 2019, 2020).

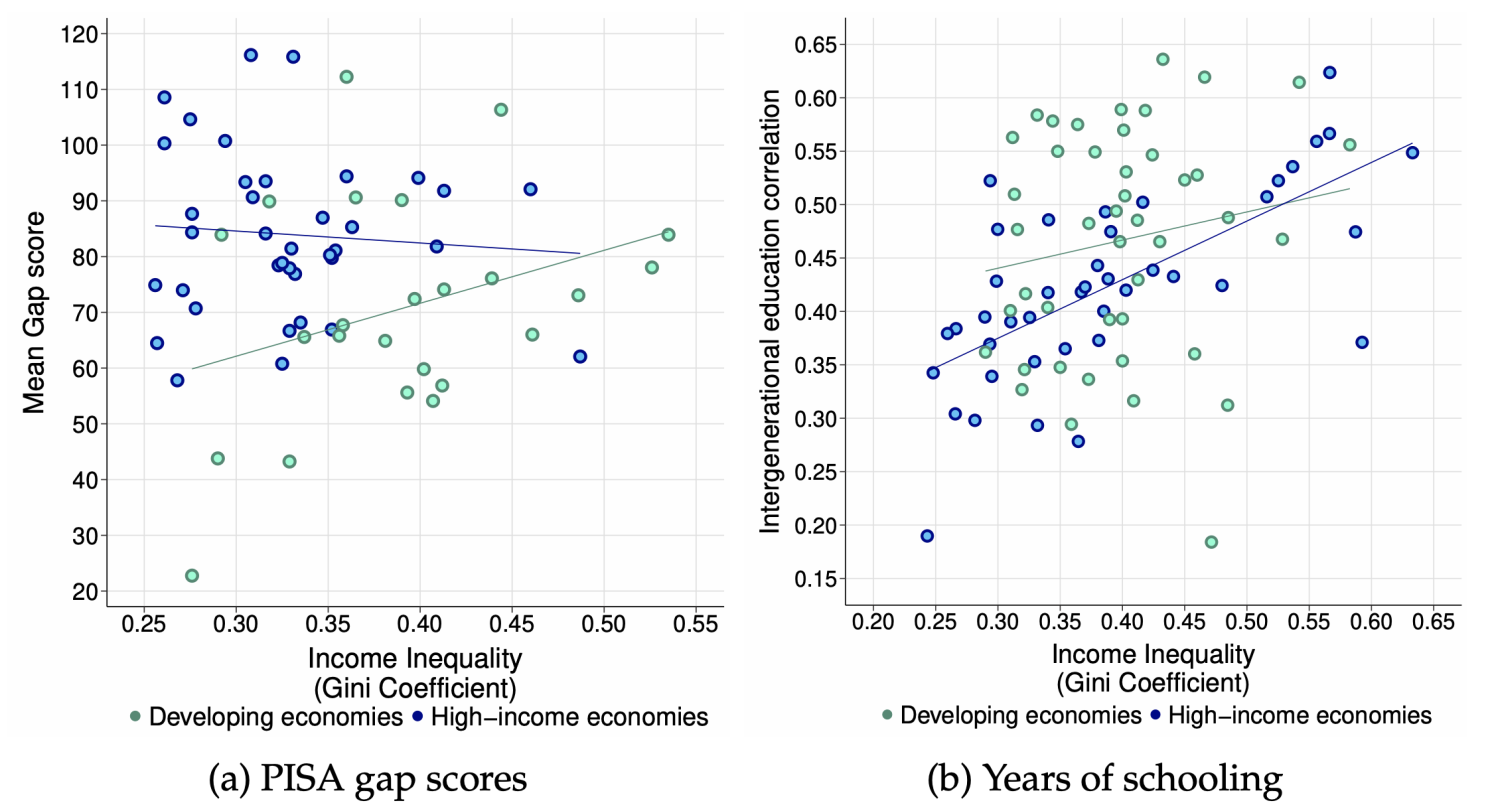

This tension motivates us to look for evidence of an ‘educational’ Great Gatsby Curve. In a new chapter for the Handbook of Economics of Education(Blanden et al. 2022), we assess whether more unequal countries also display greater educational inequality. In terms of educational attainment (e.g. years of schooling), there is indeed a clear relationship: as shown in the right panel in Figure 2, more unequal countries have lower intergenerational mobility in terms of years of schooling, in both developing and high-income economies. But the relationship between income inequality and test scores is less clear: as shown in the left panel of Figure 2, more inequality is not systematically related to larger socio-economic gaps in test scores.

Figure 2 The educational Great Gatsby Curve

Notes: Scatter plot of the 2012 World Bank Gini (or nearest available year) against the gap in average 2015 PISA scores in reading and mathematics between the top and bottom quarters of socio-economic background (Source: OECD 2016) in Panel (a) and of the intergenerational correlation in parents’ highest and child’s years of schooling (Source: Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility, The World Bank 2018) in Panel (b).

One way to reconcile these trends is that investments of well-off parents run into strongly diminishing returns, while the investments of less fortunate parents are highly productive. Then, rising investment gaps are consistent with stable achievement gaps. But even for given achievement, well-off parents may find other ways to give their children a leg up – and hence, the Great Gatsby Curve in educational attainment. From this point of view, there is indeed reason to be concerned about the future of social mobility, even if the test score gaps remain stable.

Amplifying this concern is that simple summary statistics such as the parent-child correlation in schooling may understate the true persistence of educational advantages from one generation to the next. Years of schooling is only a coarse measure of learning, which abstracts from achievement gaps between students attending the same grade and from horizontal segregation in institutional quality (Chetty et al. 2017) or field of study (Hällsten and Thaning 2018).

Educational Inequality in the Long Run

Indeed, recent studies tracking multiple generations imply that persistence is higher than indicated by conventional parent-child correlations in years of schooling. One way to show this is to note that the outcome of other ancestors remain predictive of child education, even after conditioning on parent education (e.g. Lindahl et al. 2015, Braun and Stuhler 2018, Anderson et al. 2018, Adermon et al. 2021).

That parent-child correlations may understate the role of family background is also consistent with earlier evidence from sibling correlations (Björklund and Salvanes 2011, Björklund and Jäntti 2012) or recent studies of regression to the mean on the surname level (Clark 2014a, 2014b and Barone and Mocetti 2016, 2020).

The Role of Educational Policy

While educational inequality might therefore be quite persistent, the literature is also clear about the fact that policy matters. None of these patterns and trends are unchangeable laws of nature, but they are contingent on policy choices for early childhood education, schooling and higher education, and family support.

This does not mean, however, that it is straightforward to design simple policies that comprehensively counteract educational inequality. Some of the most obvious policy instruments, such as increasing school funding or instruction hours, appear to have only modest effects (e.g. Jackson and Mackevicius 2021). Other inputs such as teacher quality appear more important, but are also less directly malleable by policy.

Given the role of economic inequality, our chapter also revisits the different ways that financial constraints affect attendance in higher education. One important insight is that student loans cannot fully eliminate the investment gap between children from families with more and less resources.

Educational Inequality in the COVID-19 Pandemic

The final part of our chapter addresses the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on educational inequality. Of the world’s student population, 94% was affected by school closures in the spring of 2020 (UNESCO), which often lasted for months and, in some cases, for more than a year. Such school closures are likely to impact children from different socioeconomic backgrounds differentially.

First, the incidence of school closures themselves varied by social background, for instance when public schools close while private schools attended by richer families stay open. Second, children from disadvantaged backgrounds might experience greater learning loss if their school closes, as the ability of parents or peers to compensate is likely to differ across families. In particular, the ability of low-income parents to respond is hampered by the fact they are much less likely to have jobs that can be done from home.

The evidence so far indeed shows that pandemic school closures have increased educational inequality. For example, Engzell et al. (2020, 2021) find that in the Netherlands, eight weeks of online rather than in-person learning led to 0.08 of a standard deviation lower test scores for students aged eight to 11. The impact is 40% larger among those in the least educated homes, suggesting that the pandemic not only increased educational inequality, but that disadvantaged children’s skills actually deteriorated.

Given that the consequences of the pandemic are ongoing, the empirical literature has so far been able to quantify only a subset of the potential channels via which it will affect educational inequality. However, learning is a cumulative process, where learning losses at one life stage may be difficult to compensate for later in life. To examine the potential long-run repercussions of the crisis, recent studies draw on structural modelling that is disciplined by both current and pre-pandemic data (Jang and Yum 2020, Fuchs-Schündeln et al. 2021, and Agostinelli et al. 2022). These studies suggest that unless there is a strong policy response, the pandemic loss of human capital will be reflected in lower lifetime earnings at the individual level, lower national income at the aggregate level, and higher educational inequality for decades to come.

See original post for references

Fund public education from the general fund and do not provide public money for private schools!

This of course requires enough and properly directed funds towards public education. Neither of which are a given, and in many instances against the best interests of those in a position to do something about it

Funding education through property taxes (as is done now) guarantees inequality. The owner class would not have it any other way.

I just through the general fund idea out because that’s the way I think it should be done.

You are correct.

I don’t think the owner class would have it any other way regardless of where the funds came from. The key is making it not dependent on what the owner class wants. As I noted in another comment, it’s probably easier for smaller countries to pull that off

Those PISA graphs make me wonder what Canada, Estonia, Finland, Korea and Japan, for example, have been doing that other countries should do. Not one-size-fits-all but more general lessons to be learned.

I believe Finland pays teachers well. Dunno about the rest.

Teachers in Finland require a Masters degree in the subject they teach as a minimum. There is apparently a strong emphasis on maintaining a consistent level of education in all schools which in practice means a lot of support for disadvantaged areas and weaker students. It could be argued that the relatively low level of immigration from ‘problem’ countries benefits the Finnish education out comes relative to, say, Sweden or other developed European countries. But it is pretty much beyond question that the Finns have gotten education policy right when compared to other countries, although of course you can never separate this from other socio-economic issues. Although given that its a relatively poor country, Estonia scores very highly too.

Aside from Japan, a commonality of those countries is that they are relatively small (population wise). I would guess that its easier to get policy right the smaller you are. less competing interests/bureaucratic hurdles, etc.

Korea is also not small population wise either. And where is China on these tables? Apparently it is/was number 1 on PISA

Having become recently involved in K-12 teacher certification (Texas), I was surprised how strictly teachers are held accountable for all student outcomes — by parents, the school, the district, the state, etc. — and all that entails: provisions for ESL or bilingual instruction, accommodating learning and other disabilities, engaging and connecting emotionally with children who are in stress or difficulty (at worst, homeless or abused), as well as gifted and talented, keeping all children’s lives safe and private, and of course prepared for the relentless frequency of standardized testing. If being supremely fluent in the content of classes (i.e., math, physics, language, history, etc.) were teachers’ only hurdle, then I don’t think this would be such a minefield. But all of the above amounts to a very stressful job, and to me this explains teacher shortages as well their very high turnover rate. Depending on the district, teachers may be forced to fund a goodly portion of their student’s activities out of their own pockets, and given their modest salaries those pockets are pretty shallow. At the same time, they are granted comparatively little autonomy: the curriculum (both what they must teach and when, the so-called “scope and sequence”) is dictated in legal boilerplate by the state, and failure to do so is grounds for dismissal (in comparison, teaching at the college, university, or graduate school level is far more straightforward, with professors — assuming tenure and not guns for hire — having almost complete autonomy). Add to that the stress of testing and student performance, on which district funding hinges. Add COVID, and the difficulty of remote instruction on crappy hardware and software. Add the military industrial-like complex of well-paid consultants and political interference from on high. We ask a lot from teachers in this country, and provide them with neither strong salaries nor prominent social position.

Having read Pasi Sahlberg’s Finnish Lessons, what strikes me most is the issue of autonomy.

In Ontario (education in Canada is a provincial responsibility — there is no Canadian department of education) public school funding comes from provincial general revenues and is allocated to school boards on a per-pupil basis. This reduces (though it cannot eliminate) the sort of regional funding inequality that property tax funding of schools exacerbates and cements.

What’s happening in Japan is that any kids whose parents aspire them to attend college or a private H.S., are spending hours a day in cram schools.

They go as a kind of after-school study session. It’s not as serious as regular school, but there are classes and teachers and subjects and it’s heavily focused on getting better test scores, i.e., to get into higher-ranking schools. It typically starts when the kids are still in elementary school and also functions as a kind of we-will-look-after-your-kids day care for school kids, allowing moms some free time in the afternoon before the kids arrive home.

Universities and even high schools are all ranked by hensachi (a standardized test score), and by middle school all students should have a rough sense of where they are heading. If they (or their parents/family) want to go to college, they start clocking large amounts of time in a cram school.

As for whether this is something to emulate… well… meritocracy, etc. etc.

Not sure about South Korea, but I gather similar to Japan. I will note that in Lee Chang-dong’s excellent film Burning (2018), the protagonist (Jong-su) comments memorably: “there are too many Gatsby’s in Korea.”

East Asian countries influenced by Confucianism give high social status to teachers? If someone is formally your teacher, you will address them as such for the rest of your life.

Finland invests very heavily in childcare, including emergency, off-hours (weekend and evening) childcare and support from birth to school age. It also compensates and supports stay-at-home mothers for their role in early childhood education, should they choose to bypass state-run daycare. They also have after-school cultural programs, such as music conservatories for school-age kids.

“A cross post yesterday about the promotion of race science provided a revealing set of comments…”

I saw that, and thought the phrase “group differences” was doing a lot of euphemistic heavy lifting in some of the comments.

What is interesting to me is that per Kendi, if you attribute “group differences” to anything other than (white) racism, you are a white supremacist, while at the same time, Asians generally have the highest test scores and the lowest crime rates, so why aren’t you an Asian Supremacist? Or at least, a Model Minority Supremacist?

Because it runs counter to Kendi’s marketing scheme. He is a race hustler. Search YouTube for the “The Glenn Show”, Glenn Loury and John McWhorter take Kendi apart and it’s fun to listen to. Here’s one:

https://youtu.be/Ey04EWAuBhA

I deliberately didn’t enter the (comments) arena yesterday, firstly because I know where all of this tends to lead, and secondly out of respect for the consistent civility of the NC comments section. I generally find the mention of “group differences” in this context an attempt to put scientific gloss on deeply held biases, and the “but Asians have the highest test scores” retort is, in my experience, usually dusted off and invoked in a defensive posture (to be clear, i’m not suggesting this is what you’re doing). By the way, growing up black in South Africa taught me that the folks in the “middle of the bus”, the buffer racial groups between myself and the whites (in this case the Indians and the “coloureds” or what in the US would be called “mixed race”) can be just as fervent in the exaltation of their own supposed superiority as the avowed racists at the front of the bus, to whom they will readily proclaim their inferiority.

In any event, I find the valorization of test scores to be a form of navel gazing, and I say this with due respect, because it takes something that is multivariate in its formation and development, intelligence, and pretends to successfully isolate the causative factors behind it down to genetics. The g-factor is multivariate, and is shaped by a confluence of factors of which genes are but only a part.

I grew up in a school system that very much believed in testing and “grouping”–something that was considered progressive at the time. Local school systems were ranked according to how many Merit Scholars they had. Perhaps they still are.

The result was that some of us got French lessons in second grade for pity’s sake and others were put on a track to trade school. I’m sure much of this is now widely discredited for public schools but the rich still send their kids to private schools to keep that grouping gig going or at least put them on a superior education track (Ivy league etc). I believe these days our local Day School teaches Mandarin (again, for pity’s sake).

Despite all of the above I’ll state my personal belief that there is such a thing as a predisposition to learn–indeed a hunger to learn–and it can’t all be put on nurture (or race either of course). Some of us took yesterday’s post to say that there’s no genetic contribution to intelligence at all. If so I don’t agree. It’s not about race but it is about something other than nurture alone. If bad actors are misusing science then that has been going on for a very long time and not just by righwingers.

Gary Nolan, the acclaimed scientist and inventor, was being interviewed by Lex Friedman once and he stated that the density of the basil ganglia plays a role in intelligence. He called it the “brain within the brain”. Interestingly, he also noted that UFO “experiencers” tend to have denser basil ganglia:

https://youtu.be/uTCc2-1tbBQ

Gary Nolan is an “experiencer”. I have come to slightly suspect that I am as well. Bear with me here, gang.

A few months ago, I suddenly had a distinct memory of a “dream” I had had as a child. It popped into my head quite clearly along with the feeling of profound weirdness that had originally accompanied it. In it, I was looking at myself laying in bed, from the angle of being at the foot of my bed.

Looking over me were three Grays.

Okay, I said in the here and now, it was a dream. You are already enough of a weirdo. This is a bit much. But I thought it might be interesting, for the heck of it, to ask my sister if she had any odd memories. Boy, did she.

When I asked her, I could practically hear her jump on the other end of the phone. She relayed that up until she was about eight years old, she would hear distinct voices, actually hear them, talking to her about her day and the things she would be doing. They were not in her head, it was as if the speaker was in the room with her. She had forgotten about it for several years but my questions had brought it back clearly.

The voices were always friendly and even helpful, telling her stuff like she was going to do well in class today. This had started when she was around six. But she knew this was High Weirdness and became scared as she grew older. One day she interrupted the voices and told them to stop. She never heard them again.

My sister has no history of mental illness. She is an extremely intelligent and capable woman who brooks no BS from herself or others. She is not given to flights of fancy and has never demonstrated the need to seek attention, in fact the opposite.

Make of that what you will.

Just to add to what I said above I think the real debate should be about the value we put on certain kinds of intelligence over others. If the meritocracy worked then why are things so screwed up? It’s the encouraging kids to group themselves that may have a lot to do with it. Public education should really be about socialization. Those who want to learn are going to do so regardless. In this day and age there are many ways to do so.

See my last sentence about the confluence of factors, which obviously include genes. But gene variance is both a within and between groups phenomenon. That said, these discussions may at some future point (soon?) become academic because the correlation between intelligence and success will mean very little in a world where we are all on UBI as AI/computers take over the traditional stomping ground of high intellect people, aka knowledge work, pushing the cost of cognitive labour towards zero.

‘Asians’ (or more to the point, Japanese, Koreans, and Chinese) have inherited a culture that merges an undisguised 19th century ‘training cogs for the industrial capitalist machine’ approach to education (in the exact same way that Japan leapt into directly copying European militaries, and in fact there’s a reason most Japanese students to this day are still wearing either vaguely Prussian military uniforms for the boys or sailor dresses for the girls) with an extreme emphasis on testing, probably ultimately descended from the insane Imperial Chinese exam hell model. There’s no pretense that education is for fun or anything resembling personal betterment. It’s to teach you raw data to pass tests to get to places to learn more data to pass further tests, with the ultimate goal of landing a ‘good’ job.

It’s a horrific system in many ways, that I think mass produces incurious, stunted individuals, but it does give you lots of people who are good at tests.

The fake ‘mystery’ of high asian test scores is easily explained by the fact that America skims off the elite, educated classes from those countries.

We’re not importing truckloads of India’s untouchables, we’re stealing all their doctors and software engineers. Same with China. It’s no surprise their kids test well.

One distinctly American feature is the ambiguous use of the term “race.” First, no one in biology wants to talk about race, the word used is generally “populations”. In old-school physical anthropology, you had “race” used to denote ancestral population groups–essentially consistent with modern studies like Rosenberg 2002 study that was able to classify populations into six classifications, with five associated with continents, based solely on DNA samples. [In contrast, something like fluency in Arabic, which is culturally acquired, would not be discernable based on biological material.]

In 19th century nationalism-type literature, “race” is used to describe ethnicity, which is characterized generally be a common language, common religion/mythology, and group taboos against exogamy. “Race” here is conflated with “nation” ergo “nationalism”. Nationality, or race, in this sense is culturally constructed because it is dependent on language, religion and customs.

In terms of medicine and disease, race in the first sense is less relevant than race in the sense of nationality, because those taboos against exogamy often lead to “founder’s effects.” Further, in terms of African genetics, Sub Saharan Africans have the most diverse genes of any of the continental population clusters because Sub Saharan Africa never had the kind of centralized governing structures like China or Europe and so populations were more isolated on a relative basis. Generalizing about Africans is probably the most suspicious and suspectable to error because this fact, on top of environmental, economic, and political difference from places like Europe or SE Asia.

On the other hand, most African American slaves came from the area in the vicinity of Nigeria and descend from Yuroban peoples, while a minority derived from the area of the Congo, so African Americans in general are not representative of continental Africans in a broad sense, although obviously with modern immigration, other African ethnicities are encountered in America these days.

Part of David Reich’s research was to isolate certain genes common to Yuroban descendants which cause a significantly more aggressive form of prostate cancer than common in other populations. Being able to screen for those genes means that doctors can provide more effective treatment for prostate cancer in those populations, whereas blank slate medicine would mean more cancer fatalities in a vulnerable population. My guess is a more race-conscious medical profession will do a better job in the future for the populations it services, especially when you will have lots of data whereby you can examine differential outcomes and make essential changes.

In matters of education, the fundamental driving criteria in todays internet world is not wealth; the key is curiosity.

Genetics will come to play a dominant role once we leave behind the hysteria of political correctness, but that is decades away.

The closest form that comes to education in America today is the pharma business.

There is a lot of money to be siphoned away from the public treasury for the future of our children.

I dont know about that. There’s plenty of curious flat earthers out there. If your curiosity isnt directed appropriately (or you dont have the resources to follow through on it) you may well end up less “educated” then even those who have little to no curiosity

I consider education to be a success if it teaches basic math and how to read.

Nothing else is required, for those curious will find the way through the jungle with those two basic weapons. Everything else is social engineering destined to fail.

The problem with this kind of analysis is that it takes “education” to be a reasonably constant variable, and so the only issue is how much of it, how many resources it gets, and so on. But anyone who’s done any teaching (and anyone who remembers their own education) knows it’s a lot more complex than that.

France has slipped so precipitously down the PISA rankings, especially in mathematics and science, that even the elites have begun to notice. The reasons for this are essentially political. For a hundred years, education was the cause of the Left: the village schoolmaster (“the cavalryman of the Republic”) was usually the bitter enemy of the village priest, and the Socialist Party was familiarly known as the Teacher’s Party” (le parti des profs.) But after the 90s, with the middle-class professional takeover of the Party, educating the masses stopped being a priority, and education became a delightful toy to play all sorts of IdiotPol games with. And once education stops being a priority, standards inevitably fall. This has been exacerbated by the rise to power of educational theorists, who dominate the creation of syllabuses and can determine the careers of teachers, although they have never themselves done any teaching. The most catastrophic example is the teaching of reading: around one in five French children is functionally illiterate at the age of eleven, and the average school-leaver has a reading age about two years lower than a century ago. In a move that would make Socialists of the nineteenth century weep, many middle-class parents now send their children to private schools run by the Church, where standards are higher.

In other words, if nobody really cares about the education of ordinary people, ordinary people don’t get the education they deserve.

James Coleman’s “Coleman Report” argued that what occurs outside the classroom is as important as the child’s time spent at school.

https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2016/winter/coleman-report-public-education/

https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2306/Out-School-Influences-Academic-Success.html#:~:text=Much%20of%20the%20work%20concerning%20out-of-school%20influences%20on,segregation%2C%20student%20and%20family%20characteristics%2C%20and%20student%20achievement.

Whether those findings still obtain, IDK.

What is the case, however, is that the literature documents divergent parenting styles in the US:

“concerted cultivation” versus “natural love.”

Concerted cultivation is where parents have the time and money to provide the child with high levels of supplementary educational and developmental resources. Natural love means the child is more or less on its own or unsupervised among peers.

This is combined with trends in marriage and family: whereas in years past, spouses may have had differing SES (doctor marries nurses aide), nowadays individuals with high levels of educational attainment marry their SES peer (doctor marries doctor). They also marry at an older age and start families at older ages, typically after both spouses develop their careers. They have lower levels of divorce. This translates to children being born into a high educational attainment, high-income household. One parent has the option of not working.

The literature contrasts that demographic with individuals with lower levels of educational attainment and lower incomes who marry or cohabit and start families at earlier ages. Statistically, these partnerships are less likely to endure. Both partners must work, or if a single parent household, that parent must work.

These trends suggest intractable inequality that was exacerbated by the pandemic.

In Ireland when I went to school they had Inspectors who visited every two to three months and conducted oral and written tests. This was in effect an evaluation of the teachers (This was in the days before “We are all professionals in our social club”). I am in Canada now and my grandchildren have some teachers that would have never got out of Teachers College in Ireland. There is nothing resembling management in the Primary and Secondary schools. My daughter recently while in a waiting room overheard a conversation where a parent was complaining about a teacher. The Principal put the teacher on an extension unknown to the caller. After the call the Principal and the teacher had a good laugh. In both Ireland and Canada teachers are well paid. The difference is that in Irish schools there are managers and in Canadian schools there are social club conveners.

Per physics stuff, gravity on a nuetron star is about 2 billion times the gravity on earth. There are a lot of assumptions baked into this article and into the comments, and, the assumptions are just social CONvention stuff, not physics stuff.

For over 40 of the last 44 years, I’ve lived in Boston or Seattle. All degrees are not created equal. Your English / Psych / History / … degree is a lot more marketable if it is from Harvard instead of UMass Amherst. IF you’re from a household in the bottom 25, 50 or 75% of household income, a Math or Chem or Stats or Physics or … STEMish degree will be more likely to open door$. IF that STEMish is from Caltech or MIT instead of the state A & M, all the better.

Oh, wait! What about the tens of millions of who are doing work which requires a fair amount of skill to keep the organization going, tens of millions of whom lack these fancy credential$? BTW – when these organizations are supposed to keep the gasoline deliverd to functioning gas stations, or the billions of calories to functioning grocery stores, or the band aids and drugs to the nurses and doctors, or the roads and power and water and sewage running to tens of millions of homes – how the hell are we-the-community helping make things work by venerating bandit$ like Mu$k, Gate$, Bezo$, Buffett … ?

THE PROBLEM is that too many at The Top are there because that is where they started, and, it is by design that the best at protecting the status quo are those in charge of the status quo. For centuries of USA life, pretty much only the affluent could afford an Ivy League degree, so those were the people to hire to be put in charge of protecting the affluent! Ta Da.

Ooops! We’ve also had this incredible science and tech revolution, so, those pesky inventors and producers of high quality and high volume steel and semi conductors and penicillin and the google and radios and … were gonna get a cut of this pie.

Get-A-Degree means Get-A-Good-Life was barely true when I was 18 in 1978, and certainly less true for those of us who’d grown up on welfare versus those of us who’d grown up with all kinds of Door$ being opened. OTOH, get a skill & stay current in the evolving skill has always increased the likelihood that you’d have some kind of choice in life. Wrapping those skills with useful credentials – an even better bet.

Otherwise, you’re depending on your MBA AND your connection$ with the Boola Boola crowd …. or, depending on the kindness of strangers.

I wanted to mention that Blacks in the US, a northern latitude area, tend to have lower Vitamin D levels which is a risk factor for osteoporosis. Black skin requires a lot more sun exposure to make bioactive Vitamin D. Blacks that live in northern climates do not get enough exposure lin comparison to whites because white skin does not block the sun as much. So it is not appropriate to dismiss the risk of osteoporosis in Blacks.