Mexico’s economy was one of the best performers of 2022, despite (or perhaps because of) a whole raft of worker-friendly policies from the AMLO government.

Amid all the economic fallout from the ever-escalating conflict in Ukraine and the West’s disastrously backfiring sanctions, compounded by the supply chain woes lingering from the still-ongoing virus crisis, 2022 was a dismal year for many of the world’s economies. But some fared better than others. They include Mexico, which began the year in technical recession but finished it on a bit of a high.

Just over a week ago, the London-based Center for Economic and Business Research (CEBR) forecast that by the end of 2022 Mexico will have dethroned Spain, its former colonial ruler, as the world’s 15th largest economy. In so doing, it will become the biggest economy in the Spanish speaking world, a mantle it is likely to hold onto for some time to come. Granted, this is just a forecast but given the wafer-thin difference between their respective GDPs and the size of the gap between Mexico’s growth rate for the first three quarters of 2022 (3.3%) and Spain’s (1.5%), it’s probably a sound bet.

A week or so later, Mexico placed sixth on The Economist‘s list of best performing economies out of a selection of 34 OECD members. From Mexico News Daily:

The magazine ranked countries according to five economic and financial indicators – Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, inflation, inflation breadth (the share of inflation basket items whose price has risen more than 2% in a year), stock market performance and government debt – and assigned each an overall score. Mexico was beaten only by Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Israel and Spain.

Mexico’s strong performance was due largely to its 3.3% GDP growth between Q4 2021 and Q3 2022 – the fourth highest on the list. Although inflation was high – at 6.8% consumer price growth and 82.4% breadth – it still compared favorably to many other countries analyzed. Mexico’s average share price dropped by 0.9%, while its share of debt to GDP fell by 0.7%.

Readers may recall that The Economist is no great admirer of Mexico’s left-leaning President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (aka AMLO). As I reported in The Empire Strikes Back Against Mexican President AMLO (June 1, 2021), AMLO was given pride of place on the cover of the May 29-June 4 edition of the magazine. Above his picture was the headline “Mexico’s False Messiah.”

An editorial inside the magazine called on Mexican voters to “curb Mexico’s power-hungry president” whom it compared with “authoritarian populists” such as Viktor Orbán of Hungary, Narendra Modi of India and Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil.

Contrast The Economist‘s depiction of AMLO with Time magazine’s near-messianic treatment of his predecessor Enrique Peña Neta, whose PRI government would end up being one of the most corrupt of modern times.

Mexican Peso: Strongest Currency of 2022

Only four largish economy currencies managed to hold their own against the US dollar in 2022. They are (in descending order): the Mexican peso (+5.37%), the Brazilian real (5.09%), the Peruvian sol (4.96%) and the Russian rouble (3.32%). While the pound sterling, the euro and the Colombian and Chilean pesos all registered historic lows against the greenback last year and even the Swiss Franc tumbled slighty, Mexico’s currency had its best year since 2012, when the currency appreciated 7.9% against the USD.

Much of the credit belongs to the Bank of Mexico, which, like Brazil’s central bank, preempted the US Federal Reserve’s aggressive hiking of interest rates by raising its own benchmark rate no less than 10 times between April 2021 and December 2022. It also helped that Banco de Mexico (Banxico for short) didn’t cut rates quite as aggressively as most of its peers during the chaos of 2020.

As I’ve noted in previous articles, Latin American countries are justifiably terrified of interest rate hikes from the Fed. When the Fed begins tightening monetary policy, it can often create a perfect storm in the region. Rises interest rates in the US raises the costs of the dollar-denominated debt of LatAm companies and governments. It can also trigger an outflow of foreign capital, which in turn heaps yet more pressure on the region’s currencies, making it even harder for both governments and companies to service their debt denominated in dollars or other foreign currencies. Rinse and repeat.

So far, Mexico has avoided this fate, helped along, of course, by higher dollar flows from exports, remittances, and foreign direct investment. In other words, an important reason for Mexico’s economy success story of 2022 is its increasingly close relationship with/dependence on the US economy, which performed significantly better than many of its advanced economy peers, particularly those in Europe. Unfortunately, that is unlikely to last.

Falling Unemployment, Greater Worker Protections, Rising Minimum Wage

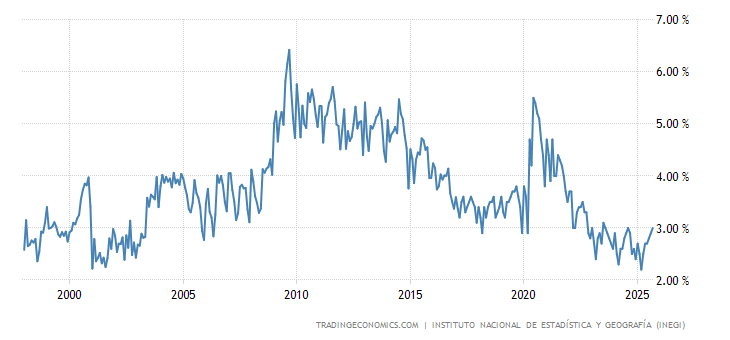

Another interesting part of Mexico’s economic success story is in the labor market. In November Mexico’s official unemployment fell to 2.8%, 1.1 percentage points lower than in the same month of 2021. It is the lowest reading since December 2005.

“The rate is at its lowest level in the past 16 years, which is undoubtedly one of the standout achievements of the year,” said Marcos Daniel Arias, an analyst at the Mexican financial institution Monex, before adding a caveat: “At the same time, it will represent an additional challenge when it comes to combating the high inflation we are experiencing.”

Interestingly, unemployment in Mexico has fallen despite (or perhaps because of) a number of unconventional worker-friendly policies from the AMLO government, including:

1. A 130% increase in the statutory minimum wage since 2018. Following successive annual hikes of around 20% per year, Mexico’s minimum wage has risen from a miserly 88.36 pesos ($4.60) a day to a much improved albeit still measly 207.4 pesos ($10.6). According to official data, just over 6.4 million workers have benefited from this sustained rise in purchasing power. The AMLO government has also doubled the amount of paid annual vacation time for all contracted workers, from 6 days a year to 12.

Mexico now boasts the seventh highest minimum wage in Latin America, climbing nine places from 2020 when it placed sixteenth. This trend has gone some way to reversing a decades-long trend of declining purchasing power among the poorest Mexicans. According to a 2014 study by economists at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, the real minimum wage in Mexico did not just stagnate from 1987 to 2014, as happened in many Western nations; it collapsed by 78%.

2. New labor reforms, including a 2019 law that opened the door to independent unionism after a century of suppression and so-called “protection contracts”, which lock in low wages as a precondition demanded by companies looking to set up shop in the country. As Kurt Hackbarth recently wrote in Jacobin, implementing the reforms will be difficult. But while progress has so far been frustratingly slow, “organized labor has chalked up a share of victories which, it is hoped, will serve as beacons for a wave of independent unionism to come.”

Just as important, new legislation was passed in 2021 that set much clearer parameters for the legal use of outsourcing and subcontracting. As I reported for WOLF STREET in late 2019, millions of jobs had been subcontracted in order to further depress labor costs, particularly in high-risk sectors such as mining:

According to a report by Ernst & Young, subcontracting structures are “commonly used in Mexico by both foreign and Mexican businesses and generally consist of a group of companies establishing one or more operating companies and one or more service companies to provide the labor component of the business activity.”

“Unfortunately”, the report adds (comments in brackets my own), “these structures have been abused” (as opposed to being used in the exact way they were designed to) in order to deprive “employees of their social security, union, and housing benefits, among others.”

In a 2019 communique, the Ministry of Labor reported that 83% of the companies that had been subject to inspection had subcontracted their entire workforce while the remaining 17% had subcontracted over 90% of their workforce. Once the labor reforms came into effect, in April 2021, companies were given a four-month grace period to get their act together. In July 2021, Mexico’s largest lender, BBVA Mexico, migrated all 37,000 of its employees who had been hired under the aegis of its outsourcing scheme to the parent company.

As even the Spanish corporate law firm Garriges noted in October this year, the reforms have been largely beneficial and not nearly as financially painful as many companies had warned:

“[D]espite the challenges and costs involved in adapting to the new rules, this reform has demonstrated its effectiveness, since it has improved the base salary for average social security contributions by almost 15% and not as many formal jobs have been lost as initially thought.”

Even before his election in 2018, AMLO had pledged to bring Mexico’s wages and working conditions closer in line with those of Mexico’s NAFTA partners, the US and Canada — something the US government was also demanding in its negotiations for the USMCA trade agreement. “We need to strengthen the domestic market,” AMLO said at a meeting on the campaign trail with the American Chamber of Commerce in Mexico.

This is hardly complex economics. By facilitating better living standards for Mexicans lower down the income scale, the government would provide a much-needed fillip to internal demand. It would also help to relieve some of the social tensions in the country resulting from extreme income inequality. Yet none of AMLO’s predecessors of the NAFTA era had even thought to pursue such a goal, for the simple reason that it contravened some of the basic tenets of neoliberal economics.

By 2016 even Mexico’s wealthiest man, Carlos Slim, one of the biggest beneficiaries of the NAFTA era and with whom AMLO has had his share of differences, agreed that it made sense to bolster Mexico’s internal market. “We need to look again at the domestic economy, which for 50 years we prioritized, and it gave us average annual economic growth of 6%. In the last 30 years we have neglected that,” Slim said at a Bloomberg forum in late 2016.

Even The Economist article conceded that AMLO has done some good things along the way, “such as bumping up pensions and subsidizing apprenticeships for the young. Though a leftist, he has kept spending and debt under control, so Mexico’s credit rating remains tolerably firm.”

Winning “Rabid” Public Support

AMLO has already partially delivered on his pledge to bolster internal demand. In the last four years working conditions and pay have improved substantially for many Mexicans working in the formal economy.

As NC reader Anonymous pointed out in a comment yesterday, this has gained AMLO “rabid support from poor people which, in Mexico, is the great majority of people.” Now in his fifth year in office, he still enjoys majority public support. And rather than hitting a brick wall and then falling off a cliff, as many companies, banks and economists warned would happen, the economy actually appears to be in ruder health as a result.

But you are unlikely to hear much about Mexico’s unconventional economic success story in the mainstream media, whether in Mexico, the US, Europe or other parts of Latin America. After all, it might encourage others to follow suit.

Over the past four years, the mainstream media has consistently derided or attacked the AMLO government’s reform agenda, including its promotion of energy security, its rewriting of the rules for outsourcing and its nationalization of lithium. Even today, most MSM coverage attributes the lion’s share of Mexico’s economic success in 2022 to “external factors”, such as increased consumer demand and investment from the US.

Every time AMLO has tried to pursue policies that generally favor Mexico’s broader economy, dire warnings erupt that investors, both domestic and foreign, will stampede for the exits. A case in point: one of AMLO’s first acts in government was to cancel a $13-billion airport for the capital that was almost one-third finished, around $5 billion over budget, mired in allegations of corruption and posed serious environmental downsides. In effect, he took his presidential predecessor Enrique Peña Nieto’s legacy infrastructure project and ripped it up, for a slew of good reasons. And in doing so, he sent a clear signal to Mexico’s business elite that the time for “business as usual” was over.

But he also made sure that the investors holding the bonds that had financed the unfinished project were paid in due course. And contrary to what many economists, bankers and media pundits had warned, investors did not rush for the exits.

Nor was there a mad stampede when the AMLO government began strong-arming domestic and global corporations into finally settling their decades-long tax debts with the Mexican state. Until AMLO’s arrival, no government had even bothered to try. Coca-Cola bottler Femsa, and brewer Grupo Modelo, a division of the world’s largest brewer Anheuser-Busch InBev, paid hundreds of millions of dollars in current taxes and back taxes. So too did Walmart and a host of other companies.

As a result, the government was able to raise more tax funds in 2020 than in 2019, without raising taxes on the middle classes. Again, no rush to the exits, though some companies, such as Canadian mining giant First Majestic Silver Corp, are still refusing to pay up.

In fact, Mexico is fast becoming a magnet for foreign investment, as corporations, particularly from the US, shift their focus from China to a production base that is similarly cheap but closer to home. In the first three quarters of 2022 Mexico received record levels of foreign direct investment, much of it from the US. According to research by the McKinsey Global Institute, American investors poured more money into Mexico than into China last year. As the NYT kindly pointed out, for American companies moving business to Mexico location is the main driver:

Shipping a container full of goods to the United States from China generally requires a month — a time frame that doubled and tripled during the worst disruptions of the pandemic. Yet factories in Mexico and retailers in the United States can be bridged within two weeks.

A coterie of Mexican business lobbies have even suggested that Mexico could become a vast investment hub for the whole of the American continent. If this happens, the biggest beneficiaries, of course, will be transnational corporations, mainly from the US. For Mexico, it will mean even closer integration with the US economy, which already accounts for over 85% of Mexican exports.

Just how much economic policy independence future Mexican governments will have under such an arrangement remains to be seen, though the answer is likely to be “not much”. The US and Canada are already locked in a trade dispute with Mexico over AMLO’s energy reforms. It also means that wherever the US economy goes — and signs are that it is heading toward a recession — Mexico will quickly follow. And what was this year a blessing could quickly become a curse.

Actually the Costa Rican Colon is up > 7% vs. the dollar in 2022. Admittedly spit in the ocean for currencies, but Costa Rica is also part of Latin America. The expat community tends to keep their money in dollars, but this new trend is starting to make people rethink their currency choices.

Thanks, Zephyrum, for the correction. I should have written “Only four largish economy currencies managed to…” Have now changed the text.

Certainly interesting to hear about the out-performance of the Colon. I wonder how many other “spit-in-the-ocean” currencies held their own against the dollar last year.

I believe that Uruguay’s peso has also outperformed the dollar this year based on this article from 6 months ago. https://en.mercopress.com/2022/06/29/uruguayan-peso-keeps-growing-against-us-dollar

As near as I can tell (and I don’t feel like I understand economics very well) the UY peso finished the year at nearly the same place as it was 6 months ago relative to the dollar.

But if it’s correct, it’s interesting to wonder how that happened, and what factors may be in play that are different from the factors that you attributed to success of the Mexican currency against the US currency in 2022:

And….

I don’t think the second paragraph applies to Uruguay

Why is the subhead “2nd strongest currency in 2022”? Which was stronger?

That was a mistake on my part, Revenant. Have amended the subheading. Thanks for the catch.

Thank for for this excellent post, Nick. It’s like if Mexico is very carefully listening to the advice of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund – and then doing the opposite. It’s one thing for publications like “Time” and “The Economist” to rail against the Mexicans for not following the neoliberal playbook, but investors have their own priority and they can see that Mexico may be on a winner. And it would not have escaped their attention that if they don’t invest their money there, then there are others waiting in the wings – such as the Chinese. And of course Mexico is lucky in having all that oil. Just today I saw a quote saying ‘More borrowing only ever makes sense if you are expecting a larger economy in the future. All economic expansion is based on energy. Countries with energy can expand, those without cannot.’ So the long term trends for Mexico may be good.

TLDR; AMLO better not go up in any small planes

Really well-done report, Nick. Thank you.

On the subject of foreign direct investment in Mexico, here’s a few snippets.

From a Lloyd’s bank report, 2020 vintage:

And a more recent piece from Dicex (logistics services):

And for what it’s worth, I see a lot of auto-rack “unit trains” moving past my section of the mid-Atlantic east-west rail system. A “unit train” is a train that consists of all one type of freight.

These trains are moving west-to-east loaded, and east-to-west returning empty.

Unit trains typically are loaded at one place, say Mexico, in this instance, and the whole train moves across one, two or even three different companies’ rails – often using the same locomotive the whole way, and not stopping anywhere to be broken up, switched, etc.

I see a lot of these unit trains loaded with automobiles with plenty of the train-cars owned by Kansas City Southern, which is one of, maybe the main north-south rail artery from the U.S. into Mexico.

KCS, by the way, was recently bought out by Canadian Pacific railroad, providing a one-company rail link from Canada to Mexico. Think on the implications of that action.

Hopefully that helps paint the picture of the trade flows, and some of the transportation efficiency evolution that’s occurring to more- tightly couple the north American economies.

Stated a different way, I wonder if Mexico isn’t becoming / hasn’t already become what Wall Street was hoping China would become?

That is, entre to new markets (Americas – South), mfg’g labor arbitrage, “financial services” (rent extraction) beach-head, and a good amount of political influence exerted by the foreign investors.

And Americas South has a lot of raw materials. A lot. A Mexican face on an essentially U.S. investor group would be helpful in relating to the rest of the Americas South countries.

Another interesting question is whether or not, as the U.S. equities market stagnates a bit till the inflation issue is dealt with, whether Mexico might not be a good place to pick up some “value stocks” if their market goes down proportionally more during the U.S. econ hiccups session.

Might not be a bad 5-year play.

Speaking of China, where is it in the “It’s All Gone Pete Tong” chart? And in China’s currency keeping up with Mexico’s currency?

As a non-OECD country, it does not feature.

An amazing statistic from the above

To be sure that’s just the minimum but I’ve read that workers in those Mexican car factories make $5 an hour or maybe one fourth what they’d make even here in the non union South. Given the huge wage disparities you have to ask yourself why wouldn’t Mexicans want to wade across the Rio Grande to a better life and why wouldn’t low skill and high school graduate Americans want to block that competition? By framing the immigration debate as being all about “racism” the good liberals in sanctuary cities are simply diverting attention from their own support for the neoliberalism that creates the problem. Meanwhile the conservatives who say they are coming to commit crimes or gain welfare are just as hypocritical. It’s all about wages–something both the liberal and conservative elites are happy to suppress.

I was also thinking about those long lines that are not stopping before they get to the US border.

And I find it hard to start cheering that some country is sticking it to neoliberalism especially when any county is stll being cheerleaded for being some other developed countries cheap labor hub.

I’m also waiting to see any substantial difference being made in the narco violence, in which US govt agencies’ “war on drugs” policies have played a part.

.

Illegal immigrants have a hard time finding work at car factories or other more regulated industries….or in industries where Americans/green card holders want to work. The auto industry is such a place…. slaughter houses not so much.

doesn’t hurt that bank interest rates for short term deposits can get close to 10% and for a year at 10%.

the article was good up to a point. yes neo-liberalsim(free trade) destroys economies, but that is the goal. destroy then rape and pillage.

but here is what the article mostly left out, the author touched on it lightly, but AMLO is a great patriotic president, but it was trump that gave him the power to do what he has been able to do.

if bill clinton, barack obama, or some other nafta democrats were in power, AMLO would find himself in prison on some bogus charges.

trump gave mexico back its sovereignty, which bill clinton stole from them

trump gave mexico its right to independent unions, trump raised mexico’s minimum wage, and gave mexicans workers a higher wage from industrial production

trump even made AMLO a success story.

foreign direct investments are actually poison to democratic control and a civil society. it should be avoided in large quantities.

NAFTA 2.0 appears to be a success. I do not follow this closely but I assume Mexico is taking back manufacturing from China.

The US is stealing German manufacturing.

I assume Texas will continue to grow as it takes advantage of Mexico’s growth and it’d abundant oil and natural gas resources.

Very grateful for this report, Nick. Shows what a leader with some guts can do. For the sake of both of our countries and the world, I hope Mexico does NOT become just another destination for American out-sourcing. Maybe I’ll send AMLO a copy of my new favorite book: “Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World” by Jason Hickel.

https://www.blackwells+bookstore+uk&cvid=b5759b72e8664a74949972f4f7945575&aqs=edge.8.69i57j0l8.9605j0j4&FORM=ANAB01&DAF1=1&PC=HCTS

Paperback: $12.79 including free shipping to U.S.

Henry Luce never met a corrupt leader he didn’t like, so it’s refreshing to see his magazine has kept to it’s roots.

Another factor that cannot be underestimated when talking about Mexico’s success is energy. Mexico can (in principle) meet its energy demands internally. It is self-sufficient when it comes to oil and has vast (albeit unexploited) gas reserves. This has protected the country from rises in energy costs. There was a point during the pandemic, for example, when it was actually cheaper to cross the border and fill your gas tank in Mexico (specially in California).

Regarding the independence of future Mexican governments… It depends on whether whoever ends up in charge has the political will to protect mexican national interests. The government’s track record is really bad when it comes to this so… Best enjoy the remaining two yrs of AMLO’s term and brace for the worst. Even if the next president is a die hard for sovereignty, there’s another problem to consider. The U.S. is not doing so good right now and both economies are deeply interrelated. There’s a very popular saying in Mexico: If the U.S. gets the flu, mexico gets pneumonia.

Excellent article. It’s nice to see well-researched information on Latin America anywhere in the anglosphere.

“If the U.S. gets the flu, mexico gets pneumonia.”

I always heard it as “If the U.S. gets the flu, Canada gets pneumonia.” But then, I was once married to a Canadian and have no Mexican ex-es. Or currents.

Well… it doesn’t surprise me, there are parallels between u.s.-canada and u.s.-mexico economic relations.