Yves here. Covid’s impact on the labor market (early retirements, avoidance of certain workplaces, long Covid) has had an upside: giving people with disabilities jobs. Despite the fact employers are not supposed to discriminate against those who have a disability, they still often have trouble getting hired. I’ve even seen an example in Mountain Brook, with our normally image conscious local gym hiring a woman for the front desk who has a mild speech impediment and gets around with a motorized wheelchair.

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

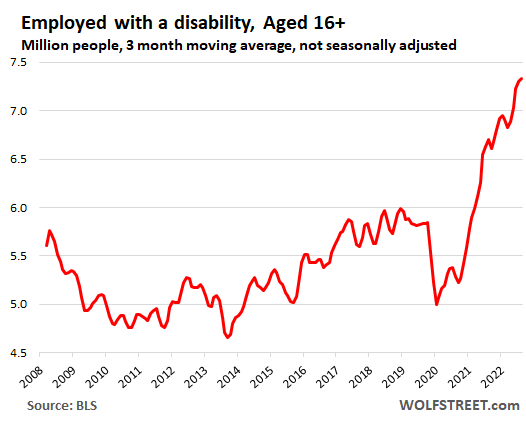

The tight labor market over the past two years has had an amazing effect on people who have a disability: An additional 1.55 million were working in January, compared to the pre-pandemic January 2020, up by 27%, according to the employment data by the Bureau of Labor Statistics today.

And according to the Social Security Administration, the number of people who applied for disability benefits, and the number of people who received disability benefits, both dropped to the lowest levels in many years.

In January, there were 32.6 million people aged 16 and over who had a disability, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Lots of times, you see the word “the disabled,” but that’s wrong. Many of them are not “disabled.” The correct term is “people with a disability.” They may be vision impaired, or they returned from a war with a limb blown off, or they have some disease. A lot of disabilities are the natural result of getting old. Many of the lucky ones that make it to 80 years have some kind of disability, and yet some still work and earn money, and you’ll find some in the US Congress, making good money too.

Others are elderly and retired; others receive disability benefits and are not working; others are wealthy and don’t need to work; others are full-time students, etc.

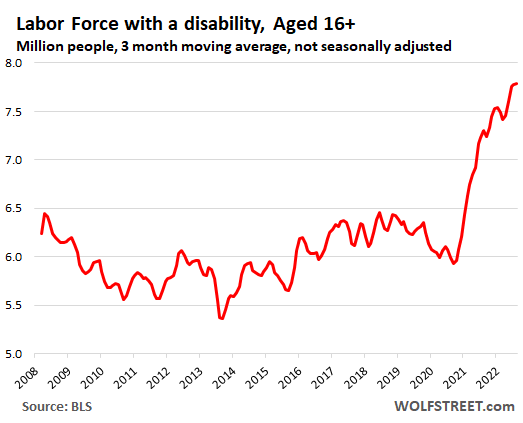

The number of people with a disability in the labor force started spiking with the tight job market in early 2021, which encourage people with a disability to go look for work, and thereby join the labor force.

A record 7.85 million people with a disability were in the labor force in January, meaning there were either working or actively looking for a job in January. This was up by 24%, or by 1.62 million, from January 2020!

At the same time, in this tight labor market, companies, beset with difficulties in hiring people to fill the record number of job openings, began opening more doors to people with a disability. (None of the data here is seasonally adjusted. To reduce some of the month-to-month variations, I used three-month moving averages):

The number of people with a disability who were employed in January spiked by 27% from January 2020, to 7.29 million in January — with December at 7.37 million having been the highest in the data from the BLS going back to 2008:

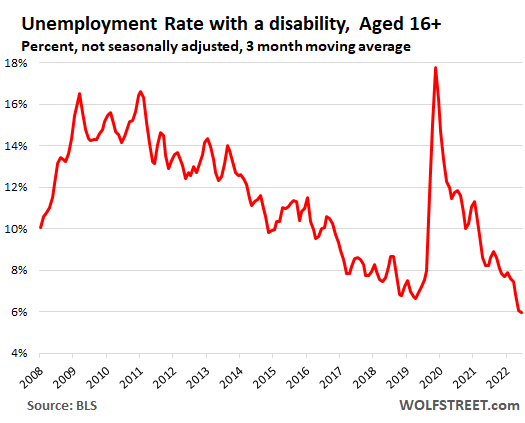

The unemployment rate for people with a disability — people who were unemployed and were actively looking for a job — dropped to a record low of 5.0% in December, not seasonally adjusted, amid a surge of seasonal hiring by the retail industry before the holidays. In January, those seasonal jobs ended, and the unemployment rate rose of 7.1%.

The three-month moving average of the unemployment rate, which irons out the month-to-month fluctuations, dropped to 6.0% in January, the lowest in the data going back to 2008.

However, the unemployment rate for people with a disability remains far higher than for the overall labor force (3.5% in December and 3.4% in January, seasonally adjusted), attesting to the difficulty people with a disability face in getting hired even in a hot labor market.

People with a disability who want to work face a harsh reality: Finding a job is tougher for them than for people without a disability. And so the unemployment rate is always higher. But as the labor market got historically tight, employers were encouraged to hire people with a disability, and people with a disability were encouraged to look for a job. The results are great to see.

Here is the thing: Over the past two years, people with a disability added 1.62 million more workers to the labor force, even as the overall labor force has not been able to recover to pre-pandemic trend due to excess deaths, a wave of retirements, and other factors, which has been dogging this labor market for the past two years.

People Applying for and Receiving Disability Benefits

There is another aspect to disability: People who apply for disability benefits with the Social Security Administration, and then the people who actually receive disability benefits.

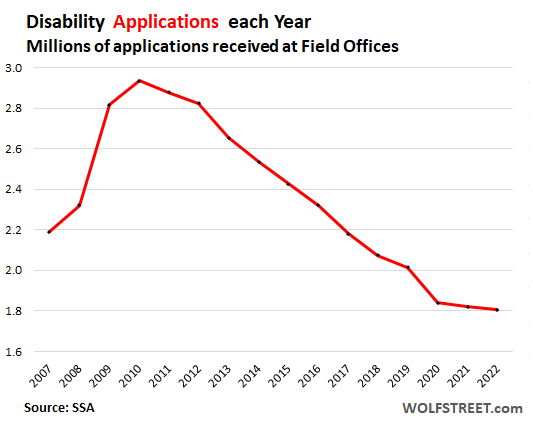

During the Great Recession, in a phenomenon that has long been discussed, applications for disability benefits spiked. Many of them might have been people with a disability who tried to find a job but couldn’t as the labor market went into crisis, and so they gave up and applied for disability benefits. Applications for disability benefits, received by Social Security Administration field offices, peaked in 2009 at the peak of the unemployment crisis, with 2.94 million applications.

Every year since then, the number of applications dropped and in 2022 fell to 1.80 million applications at the field offices, the lowest since 2003:

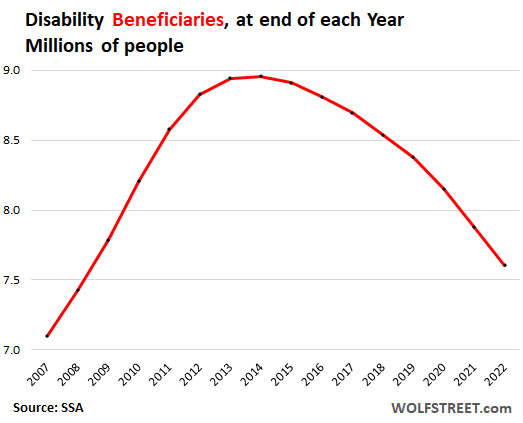

The number of people who actually received disability benefits peaked in 2014 at 9.0 million beneficiaries and has since then dropped every year. In 2022, it dropped to 7.6 million, the lowest since 2008:

I’d add a second (and unfortunately less positive) reason that more disabled people are entering the job market: disability benefits – especially for those who could only qualify for SSI and not SSDI – are abysmal, especially with the cost of housing and groceries being through the roof lately, and the SSA’s regime of blindly denying every applicant without a lawyer means it’s not even worth trying most the time. So a lot of disabled people now are stuck in factotums, working various jobs for short periods of time before getting fired/layed off/burning out from trying to keep up with jobs meant for people without disabilities. At least that’s been my experience, and I’ve noticed coworkers in similar situations.

Thanks for this comment. It takes 2 years, on average, from the time of application for SS disability to acceptance into the program, assuming you’re even accepted. If denied (likely) you can apply again, wait another 2 years for a decision, etc.

My wife’s first job out of college was as a disability examiner for our state’s social security office. Basically a bottom rung bureaucrat that would assemble relevant paperwork for the final doctors determination.

Its been 10+ years since that time, but from my recollection of her job it’s not that SSI/SSDI is blindly denying applicants without lawyers per se, it’s that the determination process relied on:

(a) an archaic, pre-hollowing-out-of-working-class-America job classification table. I.e. you aren’t disabled because you can still work x,y,z jobs that don’t exist in your area anymore.

(b) punatively low income thresholds where attempting to remain solvent or not a charity case would actively harm an application.

(c) a lot of relatively poorly compensated and motivated worker bees.

I don’t think SSA cares about lawyers all that much, it’s more that the lawyers could arrange an applicants affairs correctly to press the right buttons in the system. That may seem like a distinction without a difference, but it matters in the sense that a more humane process is possible and that systematic denial is not policy. Although I suspect part of the red tape was intentionally designed, certainly not all of it was.

I have been fighting with the federal government for disability via Social Security for 3.5 years now. It is an awful and humiliating experience. As disability applicants move up through the appeals process to higher courts, the legal processes become so complex that no ordinary person could hope to understand the intricacies. I never read any of Franz Kafka’s books, but the bureaucracy over the disability application is ominously vague yet simultaneously unforgiving—truly Kafkaesque. The Social Security Agency (SSA) has full-time lawyers on staff, presumably well-paid, whose job is to deny disability benefits for applicants.

In addition to the SSA’s lawyers, there are bureaucrats, judges, and medical experts that exude an aura of unpleasantness. Early in the disability claims process, I received a letter from the SSA instructing me to communicate and direct questions to Ms. S, the level III disability analyst. Ms. S’s role was similar to the role of ocop’s wife above. I forwarded various medical documents for Ms. S to prepare. Even though that SSA letter specifically gave me Ms. S’s phone number, she erupted in anger at me when I told her that the SSA made a mistake by unfairly sending an ophthalmological survey to my neurologist. During the hearing with the previous judge in the lower court, he (justifiably) reprimanded me for asking if the medical expert had sufficient knowledge of my rare neuropathies, for which there is scant medical literature on. The lower court judge denied me disability even though he made an emphasis in his written decision that the medical evidence and the medical expert’s testimony substantiate the herculean effort it would take me to work.

My disability case is now at the federal district court level, the third highest court in the land behind the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and, of course, the Supreme Court. Those two higher courts almost certainly will decline to hear my case. Furthermore, there are very few lawyers who have experience with disability cases at this level, even for specialist disability attorneys.

The most crucial point the SSA and I are arguing over is the timing of my disability application. According to the SSA’s definition of disability, which Sue inSoCal links to below, I have been disabled by neuropathic pain for at least eight years. It is most unfortunate that I did not apply for SSA disability until three years ago, because I had never given a thought to disability. I spent all that time studying medical literature to find some sort of answer to my rare neurological problems, but I should have started the disability application immediately. Here’s some advice I hope nobody here has to take. If you become disabled in the US, you have to apply for disability immediately. If you wait too long, you will not be disabled according to the SSA, irrespective of how incapacitating your medical problems are. This is similar to how the Bureau of Labor Statistics reclassifies an American citizen or resident who has been unemployed for two years as out of the work force. These people fall out of the official unemployment rate.

What happens over the coming decades as more and more people transition from workers to those with a disability due to Long-Covid? I don’t think that people are really talking about this one yet but it will be factor.

Edward Dowd is closely following the disability numbers from insurance companies and state/fed reports. You can find him on Twtr.

Just finished reading his book, Cause Unknown. Highly recommended.

I first learned about Edward Dowd on Naked Capitalism, and thank you, NC, for running this story:

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2022/02/bankruptcy-for-moderna-definitely-pfizer.html

How is ‘disability’ defined?

From the BLS paper cited, which I think may be this: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/disabl.pdf

“Technical Note

The estimates in this release are based on annual

average data obtained from the Current Population

Survey (CPS). The CPS, which is conducted by the

U.S. Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics

(BLS), is a monthly survey of about 60,000 eligible

households that provides information on the labor

force status, demographics, and other characteristics

of the nation’s civilian noninstitutional population age

16 and over.

Questions were added to the CPS in June 2008 to

identify persons with a disability in the civilian

noninstitutional population age 16 and over. The

addition of these questions allowed the BLS to begin

releasing monthly labor force data from the CPS for

persons with a disability. The collection of these data

is sponsored by the Department of Labor’s Office of

Disability Employment Policy.”

Also:

“Disability questions and concepts

The CPS uses a set of six questions to identify

persons with disabilities. In the CPS, persons are

classified as having a disability if there is a response

of “yes” to any of these questions. The disability

questions appear in the CPS in the following format:

This month we want to learn about people who have

physical, mental, or emotional conditions that cause

serious difficulty with their daily activities. Please

answer for household members who are 15 years and

over.

• Is anyone deaf or does anyone have serious

difficulty hearing?

• Is anyone blind or does anyone have serious

difficulty seeing even when wearing glasses?

• Because of a physical, mental, or emotional

condition, does anyone have serious

difficulty concentrating, remembering, or

making decisions?

• Does anyone have serious difficulty walking

or climbing stairs?

• Does anyone have difficulty dressing or

bathing?

• Because of a physical, mental, or emotional

condition, does anyone have difficulty doing

errands alone such as visiting a doctor’s

office or shopping?

The CPS questions for identifying individuals with

disabilities are only asked of household members who

are age 15 and over. Each of the questions ask the

respondent whether anyone in the household has the

condition described, and if the respondent replies

“yes,” they are then asked to identify everyone in the

household who has the condition. Labor force

measures from the CPS are tabulated for persons age

16 and over. More information on the disability

questions and the limitations of the CPS disability

data is available on the BLS website at

http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsdisability_faq.htm.”

Thank you!

We’re back to the 70s/80s when you needed no head hands or feet to qualify, and it took years for benefits with a lawyer. The system was opened up for speedier and more liberal processing iirc by Clinton and the backlog was cleared. Clinton, iirc, also wanted to allow some work (not Ticket to Work, as it became) so people could work some when they were able to feel productive. (You have an ailment for which you can’t predict when you can work.) I can’t recall anymore. Now the qualification is “severe disability”. End of.

As Rev said, I believe there will be some long Covid patients that will have difficulty maintaining gainful employment. I’ve heard for some folks, many cognitive symptoms are similar to MS. I predict there will be little serfs out of desperation, as shown. The grants are so incredibly low, no one can possibly live on them. But depending on your disability, I don’t see truly disabled persons (see SSA list) who cannot maintain gainful employment able to work long gig hours or maintain 30+ hrs/week for health benefits.

Rip, here’re the definitions.

https://www.ssa.gov/benefits/disability/qualify.html#anchor2

Could the number of “disabled people in the workforce” have gone up because people who are already employed become disabled but keep working, and so all of a sudden count as a “disabled person in the workforce”?

So, maybe some of the increase is due to more reasonable hiring practices. But maybe some of it is due to “abled” people who develop a medical problem but keep working and thereby turn into a “disabled person in the workforce.” I couldn’t tell from the charts if that is possible.

(Typing this again, unsure where my earlier comment went.)

I agree with Wolf that this spike may evidence systemic discrimination issues prior to the pandemic where employers wouldn’t hire people with disabilities. I would suggest another important reason may be technology and the pandemic have combined to create a huge opportunity for people with disabilities.

For example, offices are using virtual conferencing apps which come with auto-captions and transcription, so deaf and hard of hearing people can now participate somewhat. People who are mobility impaired and rely on personal support workers to do many tasks are now able to work within the comfort, convenience and dignity of home. Staying home also means not having to spend significantly more time commuting than most people would, not having to depend on unreliable special needs transit which takes a lot longer, needs pre-scheduling. Blind and visually impaired people no longer need to navigate office complexes, can even join meetings virtually from a single location within the office. The virtual office is also significantly friendlier for people who are battling disease or temporary disability, or mental health issues.

Thus the pandemic and technology have combined to create something of an equalizer. I hope this creates a culture shift which ultimately reduces the social stigma associated with disability. People need to be with and among those of us with disabilities, need to learn how to interact, before they’re comfortable with disability and impairment.