Yves here. Hubert Horan again painstakingly goes through Uber’s deliberately distorted financial results to present something much closer to a real picture. To give an idea of the level of the fabrications: Uber relies on a pet metric, Adjusted EBITDA Profitability, which excludes all sorts of cost of doing business expense, like legal expenses and regulatory settlements.

By Hubert Horan, who has 40 years of experience in the management and regulation of transportation companies (primarily airlines). Horan has no financial links with any urban car service industry competitors, investors or regulators, or any firms that work on behalf of industry participants

Uber’s cumulative losses from its actual, ongoing operations top $33 billion

Uber’s published results, which were released February 8th, showed a GAAP loss of $9.1 billion for full year 2022 (a negative 29% net margin) and positive net income of $0.6 billion (+7% net margin) in the fourth quarter. Free cash flow in the fourth quarter (net cash flows from operating activities less capital expenditures), was negative $303 million. At the end of 2002 Uber had $4.3 billion of cash on hand.

What were Uber’s actual legitimate 2022 results and how did they compare to past periods?

As has been discussed on multiple occasions in this series, Uber deliberately makes it very difficult for investors or other outsiders to answer those seemingly simple questions. Uber’s reported net income is distorted by the inclusion of claimed valuation shifts in untradeable securities that have nothing to do with the performance of Uber’s actual, ongoing operations. Instead of focusing on GAAP net income, Uber emphasizes a bogus “EBIDTA profitability” measure designed to make results look better by excluding billions in expenses that would not be excluded from a legitimate EBIDTA metric.

After Uber went public, its published earnings were inflated by roughly $7 billion due to the claimed appreciation of Didi equity it received after the collapse of Uber China ($2 bn) Grab equity received after Uber abandoned Southeast Asia ($2.2 bn) and Aurora equity received after Uber abandoned its autonomous vehicle development efforts ($1.7bn). Those claimed “profits” were fictitious. None of those companies demonstrated any potential to earn sustainable profits. Only Didi achieved the scale and market penetration to justify serious investor attention, and its equity value subsequently collapsed. [1]

This forced Uber to reduce GAAP earnings between 2020 and the third quarter of 2022, even though the paper losses were just as irrelevant to Uber’s actual business performance as the earlier $7 billion profits. But earnings inflation returned in the fourth quarter as Uber claimed that its Didi stock appreciated by $773 million. Uber made no effort to explain exactly how a company that had been delisted from exchanges, been blocked from adding new customers and abandoned by investors in the US could be confidently judged to generated this much corporate value since September. [2] More importantly Uber made no effort to explain why speculative numbers of this magnitude should be included in the headline numbers provided to investors about Uber’s current profitability.

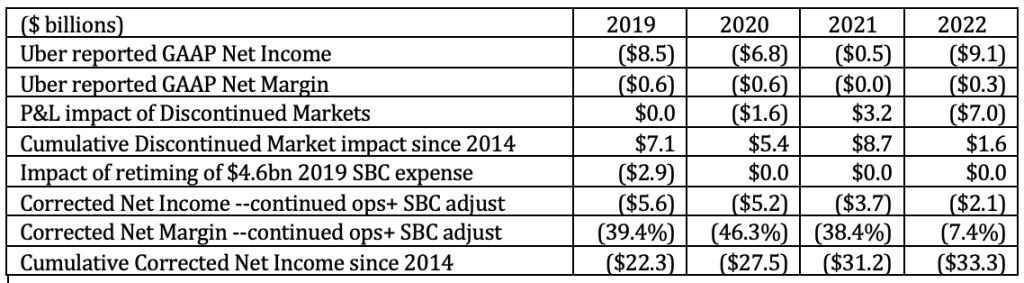

As shown in the table Uber’s 2022 GAAP Net Income from ongoing operations was negative $2.1 billion, producing a net margin of negative 7.4% and bringing a legitimate calculation of its cumulative GAAP losses to $33.3 billion. Any analysis of Uber’s financial performance over time needs to be based on these restated numbers. The distortion of fourth quarter results (not shown in the table) was especially problematic, as the claimed $773 million Didi appreciation allowed Uber to announce that it had become profitable. [3]

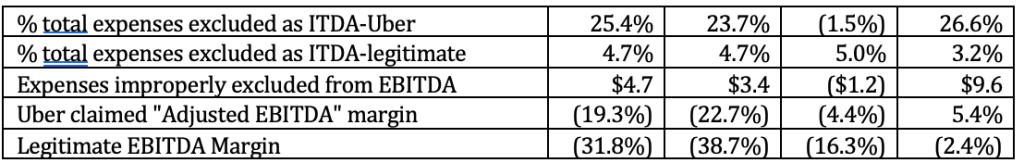

As this series has discussed, Uber’s public reports to investors downplays GAAP profitability and emphasizes a bogus “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability” metric which does not measure either profitability or EBITDA and does nothing to help investors understand changes in Uber’s financial performance.

The interest, tax, depreciation and amortization expenses excluded in a legitimate EBITDA calculation have typically accounted for less than 5% of Uber’s total expense. In order to produce numbers that make Uber’s results look much better than they really are, Uber’s bogus “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability” usually excludes a quarter of Uber’s total expenses. This improved the “profitability” Uber touts by $9.6 billion in 2022 and by $16.5 billion over the last four years. In addition to distortions caused by expenses unrelated to current, ongoing operations, Uber excludes stock based compensation ($1.8 billion in 2022) and the cost of legal and regulatory settlements ($732 million in 2022). The bogus metric allowed Uber to present an “adjusted” 2022 profit margin of 5.4% when actual, legitimate EBITDA was negative 2.4%.

In addition to “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability” Uber’s public reports try to distract investors’ attention from actual profit performance by heavily emphasizing top-line revenue growth.

In 2022 Uber’s revenue data became seriously distorted by a $3.4 billion UK-only accounting change required when drivers were reclassified from ‘independent contractors” to employees. [4] Uber failed to provide the information that would allow investors to understand how these accounting changes affect overall profitability. It does not say how big the UK market is compared to its overall revenue base, although based on the size of its “Europe, Middle East and Africa” region (15-18% historically) it appears to be roughly 3-5%. Uber does not explain why this $3.4 billion increase in 2022 UK revenue is appropriate given that it is more than 100% of Uber’s prior revenues in the entire “Europe, Middle East and Africa” region. Since Uber had been fighting these changes tooth and nail one could reasonably assume that the net P&L impact is negative, but Uber failed to document any of the offsetting “Cost of Revenue” expenses. Perhaps a full and transparent accounting of these impacts could resolve these issues but Uber apparently doesn’t want investors to know what the net P&L impact of driver reclassification is and wanted to be able to highlight artificially inflated 2022 revenue growth numbers.

Uber’s deliberately opaque and misleading financial reports have always been designed to prevent mainstream business media reporters from understanding Uber’s actual performance, so that their stories are limited to Uber’s preferred PR narratives. Stories about Uber’s February 8th announcements emphasized Uber’s top-line revenue growth and endorsed Uber claims that this “strongest quarter ever” and that it had done a much better job than other tech companies in “staving off the downturn” while ignoring the multi-billion dollar accounting adjustments behind the revenue growth numbers. Stories highlighted that Uber had been “profitable” in the fourth quarter, without explaining the huge distortions in all “Adjusted EBITDA Profitability” numbers or that the alleged fourth quarter number had been totally driven by the claimed appreciation in untradable Didi stock. None of the stories in major business publications mentioned Uber’s reported 2022 loss of $9.1 billion or any other GAAP numbers. [5] There is no way to say whether the problem is that Wall Street Journal and New York Times reporters and editors are financially illiterate, or whether they are deliberately trying to mislead their readers.

Uber reduced losses by capturing billions that had previously gone to drivers

As the adjusted numbers show, Uber has significantly reduced its losses. Its GAAP net income from ongoing operations, which had been negative $5.6 billion in 2019 are now only negative $2.1 billion. Net margins have improved from negative 39% to negative 7%.

Investors would want to understand what has driven these improvements and whether those improvements might continue and allow the company to achieve sustainable profits in the near future. But Uber’s reporting is designed to prevent investors from answering those questions, and Uber’s does not provide investors with any explanation of recent changes or how those changes might future P&L prospects. To what extent were recent changes the result of one time events or accounting changes versus productivity or marketing improvements that might be ongoing? Uber doesn’t even allow investors to understand how demand volumes and prices in its different businesses and regions have changed, or how pricing changes have affected demand growth.

The two biggest recent changes in Uber’s economics are major price increases since the onset of the pandemic, and Uber’s ability to capture a much larger portion of customer payments since early 2022. In the years prior to the pandemic Uber’s strategy was based on extremely aggressive prices and capacity growth designed to fuel the extremely strong top-line traffic and revenue growth it believed that investors were focused on. As this series had discussed in detail, this produced massive losses and there was no evidence that Uber had any idea how to produce sustainable profits under this strategy. When the ridesharing business was devastated by the pandemic, Uber was forced to put greater emphasis on the much lower margin delivery business, and to refocus on reducing ridesharing services and raising fares.

The data Uber provides is limited to aggregate revenue and trip volumes (rides plus delivery combined). This obviously masks margin and competitive differences between the two businesses and accounting issues such as UK driver reclassification, but this is all an outside observer has to work with.

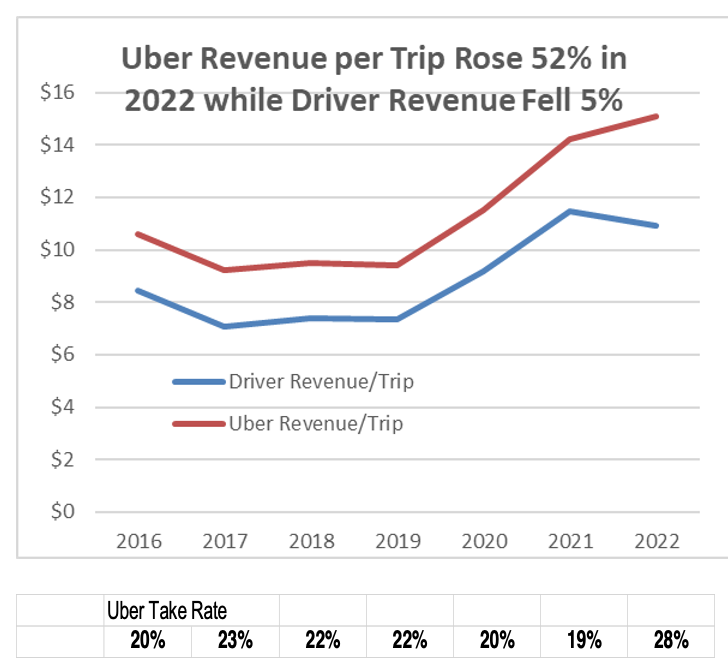

Pre pandemic total customer payments per trip had averaged roughly $9.50, with Uber getting a little over $2 (22%) and drivers getting a bit more than $7 (78%). 2021 customer payments per trip were 51% higher than 2019 levels, but Uber revenue/trip increased only 34% as the portion of low margin delivery trips increased and because Uber needed to give a higher share to drivers (81%) in order to keep service levels from collapsing.

But as ridesharing demand was recovering in 2022, Uber managed to increase its revenue per trip by 52% ($4.17 vs $2.74 in 2021) while forcing drivers to accept less revenue per trip (down 5% from $11.46 in 2021 to $10.93). During 2022 Uber implemented “upfront” pricing schemes that uncoupled driver payments from customer fares. Drivers no longer had any way of knowing what customers were paying or what share of the steadily increasing customer fares they were getting. This allowed Uber to improve its margins by charging the highest fares it thought passengers would pay, while paying drivers the lowest rates it thought it would take to get them to accept trips.

Drivers were only getting 72% of each customer dollar in 2022 while Uber’s share had increased to 28%. Drivers would have received $6.5 billion more in 2022 if fares were still being split on the pre-pandemic 78%/22% basis, while the additional $6.5 billion in revenue was pure profit for Uber and was crucial to offsetting higher costs in other areas. This wealth transfer does not reflect the total decline in driver take-home pay per trip, since they have been facing huge increases in fuel and vehicle costs.

It is difficult to see how Uber could achieve the similarly large margin improvements in the next few years that would be needed to produce meaningful, sustainable profits. This would require both getting customers to pay higher and higher fares and getting drivers to accept smaller shares of customer payments. Marginal gains are always possible but it is difficult to see 2022 magnitude gains (improving Uber take rates by more than 6 points) occurring again. Continued market growth would do very little for Uber’s P&L if the share of customer payments remains constant. There is no evidence that Uber has any way to improve operational efficiency enough to boost its P&L by billions.

The chaos of the pandemic (and pandemic recovery) masks the questions of when customer resistance to higher fares and driver resistance to low payments reach the critical points usually seen in competitive markets. Compared to the traditional taxis they replaced Uber has cut driver compensation and is now offering riders much less service at higher fares. Multiple stories report the magnitude of fare hikes in selected cities and growing driver discontent [6] but (by design) Uber’s refusal to publish basic pricing and demand data limits the awareness that its reduced losses depended on reduced customer and driver welfare.

The collapse of “tech” equity has had little impact on the demand for Uber stock

The central issue affecting Uber’s future health and viability is whether it can maintain a robust demand for its equity. Quarterly P&L results are relevant to stock prices, but the link is indirect. It is more important to understand the factors that have driven the major recent collapse in the valuation of a wide range of “tech” companies similar to Uber.

Following Uber’s lead with taxicabs, hundreds of venture capital funded US startups in the last decade constructed narratives about how their innovative technologies would allow them to “disrupt” established industries such as car selling, real estate, logistics, fashion, and investing. Those narratives highlighted how they were following the model established by the successful unicorns of the previous decade (Google, Amazon, Facebook) including a strict initial focus on hyper-aggressive top-line revenue growth (in the expectation that profits would follow later), richly valued IPOs and strong ongoing equity appreciation.

Over the past 18 months all of the narrative claims those post 2010 startups made have fallen apart. None of these vaunted disruptive new technologies have created powerful competitive advantages in the industries they were trying to “disrupt”. The overwhelming majority of these companies have never earned a dollar of legitimate profits and none have produced healthy, sustainable profits. None had the powerful scale or network economies that might have justified their excessive focus on top-line revenue growth.

The bubble sustaining the demand for the equity of these narrative-driven startups burst in late 2021. By the end of 2022, the value of 23 of these companies had fallen more than 85% and another 14 companies experiences stock price declines of 75-84%. [7] The Ark Innovation ETF, which explicitly tracks these types of startups was down 80%. Softbank, the largest investor in these types of startups (including Uber) lost $5.9 billion in the fourth quarter of 2022. [8]

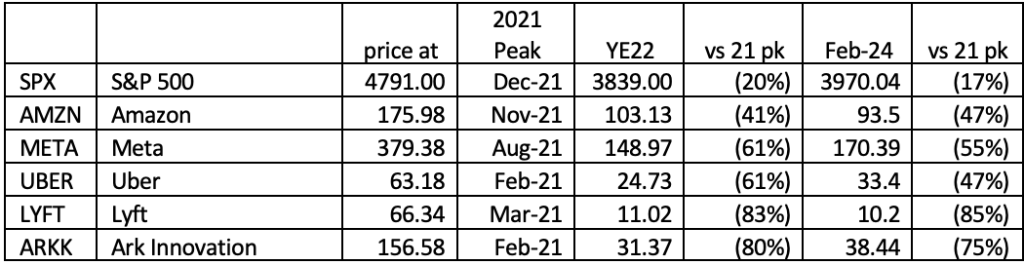

The overall stock market was declining during this period as investors recognized that the Federal Reserve’s shift away from near-zero-interest rate policies would increase the risk of equities. At the end of December the S&P 500 was down 20% from its 2021 peak; thanks to a recent uptick due to speculation that the Fed would slow down interest rate increases it was down 17% as of February 24th.

The much larger collapse of these narrative-driven “tech” companies demonstrates the market’s growing awareness that it could no longer shrug off the much greater risk of companies that had never demonstrated compelling competitive advantages or any near-term prospect of earning sustainable profits. This also led the market to begin rejecting other risks that had not been properly priced, including SPACs and crypo-related companies, and even seriously began marking down the inflated values of strongly profitable pre-2010 unicorns such as Meta, Facebook and Google. [9]

But the growing awareness that pre-2022 equity values of ‘tech’ startups were driven by a “consensual hallucination” created by artificially manufactured narratives and the illusion that Federal Reserve policies had eliminated normal startup risks has not yet affected the market for Uber stock. As of the end of 2022 Uber was down 61% but is up 35% since then so it is only down 47% as of February 24th. This was a substantially smaller decline than seen at the bulk of the other narrative-driven “disrupters”. Ark Innovation is still down 75% while Uber’s declines are in line with companies with long histories of strong profitability like Amazon (down 47% as of February 24th), Alphabet (down 40%) and Meta (down 55%).

Even though Uber is still structurally unprofitable, and no one has laid out a public argument as to how it might achieve sustainable profits, Uber is still valued as a $67 billion company. All the Wall Street analysts following Uber are predicting this value will materially increase; none think Uber’s economics are in anyway comparable to the many other narrative-driven “tech” disrupters (e.g. Carvana, OpenDoor, Snap, Zoom, DoorDash, Rocket) whose corporate value has completely collapsed.

The stock market’s evaluation of Uber vs Lyft has dramatically diverged

On February 9th Lyft announced a full year 2022 net income of negative $1.6 billion (versus negative $1.1 billion in 2021) and fourth quarter 2022 net income of negative $588.1 million (versus $283.2 million in 4Q21). Lyft reported $1.8 billion cash on hand at the end of 2022.

The stock market’s valuations of Uber and Lyft had followed parallel paths until mid 2022 and it is not clear why such a radical divergence occurred. Lyft’s stock price was down 83% from its 2021 peak at the end of December. There was no 2023 bump; it was still down 85% on February 24th. There is no meaningful difference between the underlying economics of the two company’s ridesharing operations. But the market clearly began valuing Lyft in line with the many collapsed “tech” disrupters, while believing that Uber’s future prospects were substantially better, and much more comparable to the vary large scale profitable tech companies.

Business press reports on Lyft’s earnings report noted that Lyft issued unexpectedly pessimistic revenue guidance for the first quarter of 2023, even though it had beaten Wall Street revenue and profit estimates for the fourth quarter. None of these reports attempted to explain why the market’s much more negative view of Lyft had developed six months ago, or attempted to explain the increasingly divergent valuations in terms of anything Uber was doing better, or in terms of likely near-term P&L performance differences. If one carefully restates earnings to adjust for accounting anomalies and irrelevant items, one would see that Uber margin gains have been stronger than Lyft’s but none of the industry observers have done that and none have offered any public explanations as to what has been driving Uber’s better performance. [10]

There has been some speculation that Uber is now in position to drive Lyft out of the market and benefit from vastly less competition. Lyft CEO Logan Green noted a weak current pricing environment given Lyft’s need to “remain competitive within the industry.” This suggests that Uber may have been keeping fares down, not only to boost its top-line traffic numbers but to increase pressure on Lyft.

While this is a topic that has not even been hinted at in the business press, few things excite the stock market more than the elimination of competition, and this might explain some of the current divergence in Uber/Lyft valuations. But Uber can’t realize those kind of gains (e.g. big increases in market power over consumers and drivers) unless Lyft approaches the verge of liquidation, and there’s no evidence that’s a near-term possibility. To the contrary, Lyft will presumably do everything possible to fight for survival, producing market share battles which would hurt both company’s dismal margins.

Lyft has always been a distant number 2 to Uber, but there’s never been evidence that passengers have any willingness to pay higher prices just to ride with the bigger company. It is possible that Uber has figured out ways to get wealthier customers to pay higher fares, or to get drivers to accept lower compensation while keeping them from realizing that they are getting an increasingly lousy deal, but those would not seem to be things that Uber could increasingly exploit to maximize pressure against Lyft.

Any investor expectations that Uber could buy Lyft and merge them out of the market would appear unrealistic at this point. Unless Lyft thought the risk of liquidation was imminent, they would demand an extremely high acquisition price. Unlike the situation when companies like Google and Facebook bought out competitors, Uber is not in a position where it is flush with profits and can pay for acquisitions with extremely valuable and rapidly appreciating stock. And antitrust authorities would fully recognize the purely anti-competitive nature of any Uber-Lyft merger and would recognize that Uber has none of the popular support that companies like Google and Facebook enjoyed when they pursued anti-competitive mergers.

_____________

[1] The issues with Didi’s profitability–despite massive market advantages it had versus Uber (95%+ market share, much lower car ownership rates, cities that were much larger and denser), were discussed in Can Uber Ever Deliver? Part Twenty-Five: Didi’s IPO Illustrates Why Uber’s Business Model Was Always Hopeless, August 2, 2021

[2] Some speculative uptick in demand for unlisted Didi equity is possible but Beijing did not lift the ban on adding new users until January and the potential relisting in Hong Kong remains hypothetical. Silva, Marco, DiDi Global: Get Out While You Still Can, Seeking Alpha, Nov 15, 2022; Huang, Raffaele, Didi Wins Approval to Restart New User Registration for Ride-Hailing Service, Wall Street Journal, Jan 16, 2023. Uber had announced its intention to dispose of its Didi stock, but it is unclear how this could be done without crashing the values, especially in the absence of a healthy exchange-based trading. Briançon, Pierre, Uber Considering Shedding Its Stake in China’s DiDi Global, Barrons, 15 December 2021;

[3] Uber Part Twenty Nine (February 11, 2022) presented a more detailed version of this table showing financial results from 2014 through the end of 2021. That table, and the 2019 column of this table, also adjust published results to spread stock based compensation (SBC) expense realized immediately after Uber’s 2019 IPO across a longer time period. In this case Uber was following proper accounting practices; it could not report these as current expenses until the day they actually vested, but this produced third quarter 2019 Uber P&L numbers wildly out of line with all other time periods.

[4] If drivers are employees, everything passengers pay should be included as “Uber revenue” and all regular and incentive payments to drivers should be included as expenses under “Cost of Revenue”. If Uber, as it has long claimed is merely a passive intermediary providing software that helps independent drivers find customers, then only Uber’s cut of passenger fares (what drivers are paying for Uber’s software and brand support) should be included as “Uber revenue” and all other driver expenses (vehicles, fuel, hourly pay) are irrelevant to Uber’s corporate P&L. Uber said the impact of the UK accounting change on its reported revenue by quarter was $200 million, $893 million, $1.1 billion and $1.2 billion. Driver reclassification also means that Uber is liable to collect value added tax (VAT) on passenger fares that small-scale independent drivers would not be required to collect. The UK fined Uber $732 million in 2022 for its past failure to collect VAT. As with the changed revenue accounting, Uber’s SEC reports are designed so that it is impossible for investors to figure out what the net P&L impact of driver reclassification will be going forward

[5] Browning, Kellen, Uber Reports Record Revenue as It Defies the Economic Downturn, The New York Times, Feb 8, 2023; Needleman, Susan, Uber Shares Rise After Ride-Hailing Company Reports Revenue, Profit Growth, Wall Street Journal, Feb 8, 2023

[6] Jeanette Settembre, Uber ‘taking advantage’ of unsafe NYC with astronomical fares, New York Post April 15, 2022; Henry Grabar, The Decade of Cheap Rides Is Over, Slate, May 18, 2022; Asher Schechter, “Uber Has Higher Prices and Worse Service Than the Taxi Industry Had Ten Years Ago”, ProMarket, July 28, 2022; Lee, Timothy B. What Shocked Me Most When I Became a Lyft Driver for a Week, Slate Dec 22, 2022 (“How much passengers were charged, how much I took home, and that somehow this company is still in business”); Salam, Erum, Uber drivers strike in New York after company blocks raises and fare hikes: City agency approved raises for drivers by 7.42% per minute and 23.93% per mile but company filed lawsuit, The Guardian Jan 5 2023; Sherman, Len, Uber’s New Math: Increase Prices And Squeeze Driver Pay, Forbes, Jan 6, 2023; Hu, Winnie and Ley, Ana, Uber Drivers Say They Are Struggling: ‘This Is Not Sustainable’, New York Times, Jan 12, 2023; Rodgers, Sophie, Uber and Lyft used to be much cheaper than taxis. Now cabs are leveling the playing field, Crains’s Chicago Business, Jan 27, 2023; Wehner, Greg, New York Taxi union to strike against Uber and Lyft at LaGuardia airport, Fox Business, Feb 23, 2023

[7] Companies whose December 2022 equity values were 95% or more below their 2021 peaks include Carvana, Vroom, Fubo TV, Opendoor, Upstart, RealReal, Redfin and Blue Apron; 94-90% down: Affirm, Lending Tree, Beyond Meat, Virgin Galactic, Pelaton, Teledoc Health, Good RX, and Roku; 85-89% down: WeWork, AMC,Twilio, Snap, Robinhood, Zoom, Rivan Automotive; 84-80% down Draft Kings, Lyft, Rocket, Palantir, Zillow, SoFi Technologies, Cloudflare and Door Dash; 70-79% down :Spotify, Grab, Warby Parker, Car Gurus and Pintarest. Wolf Richter’s Wolf Street blog has been tracking these “Imploded Stocks” that had been inflated due to market-wide “consensual hallucination”

[8] Fujikawa, Megumi, SoftBank Loses $5.9 Billion in Quarter as Investments Suffer, Wall Street Journal, Feb 7, 2023

[9] Thompson, Derek, Why Everything in Tech Seems to Be Collapsing at Once, Atlantic, Nov 17, 2022; Goswami, Rohan, Tech’s reality check: How the industry lost $7.4 trillion in one year, CNBC, Nov 25, 2022; Richter, Wolf, 2022, Year of Face-Ripping Bear-Market Rallies that Got Crushed, Wolf Street, Dec 30, 2022; Richter, Wolf, The Most Astounding IPO Hype-and-Hoopla Show Ever Ends 2022 in Tears, Wolf Street, Dec 26, 2022; Waters, Richard, Investors look for bottom of tech sector downturn, Financial Times, Jan 19, 2023

[10] Sumagaysay, Levi, Lyft stock closes lower than $10 for the first time; three-quarters of its valuation has been wiped away this year, Marketwatch, Dec 28, 2022; Bellan, Rebecca, Lyft shares get crushed on weak guidance for first quarter, Techcrunch Feb 9, 2023; Feiner, Lauren, Lyft shares tank 30% after company issues weak guidance, CNBC, Feb 10th 2023

Hubert, I know I’ve said this to you before, but I’ll say it again: Turn this series into a book. I know I would buy it and I’m sure that a lot of other NC-ers would too.

If you have to publish it as an eBook first, and, if demand warrants, publish it in, oh, a trade paperback.

Agree.

Same thought here. When Uber finally implodes under its own weight, Hubert Horan will definitely be the go-to guy to find out the history of them and how they evolved.

The only thing stopping me from saying I’d buy it as a book today is the knowledge that the story is still being written!

Hubert has posted PDFs of the entire Uber series on his website:

https://horanaviation.com/publications-uber

Thanks to Hubert Horan’s research and reporting, and the observed behavior of Uber, I’ve reached the conclusion that the company is a hybrid of innovative control fraud (the inside game) and Loss Leader For Capital (the outside game), in which investors are willing to sacrifice returns in exchange for the far more renumerative effects Uber has had in eroding labor standards; whatever losses Uber has sustained over the past decade pale in comparison to the aggregate profits realized through their brutalist expansion of the gig economy.

Maybe a naive question… why isn’t Uber forced to report using GAAP?

Nominally they do report GAAP numbers. They exploit the fact that there has always been a lot of leeway in exactly how you organize GAAP numbers. Under GAAP you can report numbers about the ongoing core business and you can report numbers about assets that have nothing to do with the ongoing core business. Prior to 2018 Uber did what most companies do, clearly segregating these line items so investors who wanted to understand the financial performance of the ongoing core business could easily see the relevant numbers. After that, Uber combined them, falsely implying that the outside securities it obtained after closing down failed operations were integral parts of the ongoing core business, and falsely implying that after the IPO Uber was much closer to real profitability than they really were. Thanks to GAAP you can figure out which line items are which, and calculate results for the ongoing business (as I’ve done) but it takes a bit of work.

Because of how Uber conflates these items its bottom-line GAAP net income numbers can swing wildly from year to year in ways that have nothing to do with swings in the ongoing core business. Uber knows that financial reporters are too lazy to do the arithmetic that would produce the relevant numbers (and in fact too lazy to read NC where all the needed adjustments have been laid out). And knows that since the reporters don’t understand the wild swings in GAAP Net Income, they will just ignore them and place much greater emphasis on the bogus non-GAAP numbers Uber management is trying to emphasize.

Hi Hubert, an excellent update on the dumpster fire but no cold shower of reality seems capable of putting it out. Must be an electric vehicle!

On the UK revenue adjustment, it doesn’t look as egregious to me.

– The $3.4bn is the total revenue because Uber is now collecting the whole fare and its drivers are an expense

– the Uber percentage of trip revenue (from the graph you post later) of 20% implies that the UK Uber commission would have been be c. $700m (NB the red line is incorrectly labeled “Uber” when it is the total of driver + Uber revenue, is there no stunt they won’t pull to lipstick the pig?).

– If the UK Uber commission was 20% of the EMEA revenue, then you expect the UK revenue adjustment to be equal to 80% (100%-20%) of the previous year’s revenue, I.e. a change of less than 100% as you suggest.

– If the UK market is lower margin than 20%, say 10%, then $3.4bn is the fare revenue corresponding to $340m of former Uber commission and the EMEA market is 5x or 6x $340m, I.e. $1.7bn-$2.04bn and the UK revenue adjustment of $3.4bn-$340m, I.e. $3.06bn, is 150%-160% of previously stated fare commission.

So I think the implication of the >100% adjustment is not so much that the new numbers are suspect but that the old numbers hid poor marginality in the UK.

I agree that we should see the expenses of the rides presented under the new UK revenue model. Perhaps they have been hidden in a note somewhere in 2022 as provisions against legal liabilities and will only show up in 2023 as payroll costs? Which as a one-off will have been left out of adjusted EBITDA….

Revenant’s explanation makes sense. Essentially, what used to be considered as Bookings in the UK is now recorded as Revenue. But of course Uber deliberately chooses opaque and confusing language to mask insights on its operational and financial performance, leaving us to speculate on how to translate Uber’s artful wording.

I remain doubtful that their adjusted global mobility take rate is really only 19.8%, given their upfront pricing mechanisms on both sides of the marketplace, abundant driver supply in the US and recent rider price increases.

Huran’s reports, from the start, led me to a similar conclusion: the big boys’ investments are in deregulation more so than Uber.

The fact that Uber’s public valuation has struggled to breach its last valuation as a private company ($75bn), and that the current valuation is lower than its IPO valuation of $69bn (after first day of trading) flies in the face of the “high flying stock” talk the evangelists in the financial press are keen to promote. The reality, as has been painstakingly demonstrated with Hubert’s NC series, is that Uber has no line of sight to profitability and therefore has no choice but to keep padding the narrative and weaving a tangled accounting web to keep the gig going a little while longer. As for the narrative driven startups who saw their valuations get massive bumps from pandemic induced demand, a not insignificant number of those have been hit by the mean reversion re: valuation multiples and are now worth less than the preference stacks on their cap tables, so many may not survive the mega shakeout of 2023/24 .

Thank you Mr Horan once again for your continuation of this excellent series. Uber’s continued existence really does seem to be a good example of Keyne’s famous market irrationality quote.

Did anyone else get served ads for the Uber driver app with this article? I’m not sure whether this is evidence of the Google ad AI having a dark sense of humour or just being remarkably useless.

I get those ads on YouTube, and lemma tell ya, whoever is scheduling Uber’s ads needs to get a clue and soon. Well after the start of the New Year, I was still getting holiday season-themed ads for Uber.

Good grief. You know what looks more out of place than holiday decorations in mid-January? Uber ads that feature them!

Didi shares are listed and trading in the United States.

Symbol: DiDi Global Inc. (DIDIY)

The 52 week range is $0.68 to $5.05 per share and at the moment the shares are $4.11.

Volume so far today is 3.2 million shares.

96% of the float is sold short and it costs 18% per year to borrow shares.

Two observations:

1) UBER could have used this security as a surrogate for what it really owns (the HK delisted shares).

2) If UBER had marked their shares down low enough, showing a MTM gain might be possible.

What comes to mind of course is the SFB/FTX token price manipulation . . ..

I think any analysis of Uber should start considering which structural advantages they have vis-a-vis taxis and the wider transportation market. A search for “white label taxi apps” turns up a lot of different companies that can easily allow anyone to compete with Uber in a given market and most old school taxis are now connected to a booking system. With the push to reclassify Uber drivers you’re getting into the weird situation that Uber is now forced to internalise costs that competitors contracting with taxis don’t have to internalise. It’s hard to see how Uber can maintain 28% margins in such a situation.

So let’s go over these: the core service of pressing a button and getting a car is a commodity now. There’s little opportunity to differentiate the core service and no reason to think 28% is a sustainable margin in the market (at least for the software portion). 28% does seem like a fine margin if you need to insure yourself against something bad happening in the car with Uber being liable for the conduct of the driver, especially in markets where Uber accounts are stolen or traded. The 28% also needs to cover costs connected with driver churn. These are expenses Uber has internalised but that an app that contracts with taxis would externalise (for instance by letting a city taxi commission inspect cars and do driver background checks). Taxi apps also have a better claim to the drivers being independent and them just connecting riders and drivers as taxis can otherwise be hailed on the street and taxi pickup lanes to get passengers.

The opportunities for Uber in this situation basically boils down to hoping cities don’t license enough taxis (as has happened in New York) or people don’t trust taxis (as happens in Latin America for instance). Neither seem like a sustainable strategy, since cities can liberalize their taxi code (as for instance Copenhagen has done with Uber leaving soon after) or people might learn to trust taxis (either because Uber gets a worse reputation or taxis get a better one). Both of those changes erode the value of Ubers core asset, namely drivers that can not offer rides outside the Uber system (since Uber and taxi drivers go through different processes). In Europe you’re already seeing a wealth of taxi hailing apps and seeing as they can often offer similar pickup times as Uber (especially if you hail on multiple at once) it seems there’s few network effects.

Now there’s still the question of how Uber can still grow and why they’re received so differently by the market than Lyft. The easiest explanation would be that taxi services is a market where cities have been underserved given both companies an opportunity to expand the markets when they enter them, but that them entering a market ends up sufficiently changing market dynamics as to make their business model unsustainable. As such it’s hard to see where Lyft would find growth given they are so far only in North America, whereas Uber can better hide badly performing markets behind better ones.

At the end of the day it just seems like taxis are an inherently local business and in a healthy business environment lots of people would see the opportunity offered by 28% margins and start competing for those rides locally. That’ll be true regardless which shiny new short term growth Uber is trying to distract us with.

Yes, Hubert addressed these issues early in his series. Uber has no cost advantages over traditional cabs and is in fact a higher cost producer. There is nothing complex or distinctive about its app, so no barrier to entry there.

Ola/Uber have dramatically increased prices in India after driver protest. New ride share apps have popped up facilitating car pooling at very low cost. High usage at higher prices is a dream

Another fascinating instalment. Thanks Hubert.